ABSTRACT

Research shows that plant-based diets help reduce the impacts of climate change and that people who adopt plant-based diets tend to have more proenvironmental attitudes. However, recent work has highlighted that people can have very different reasons to eat meat or be vegetarian, opening up new opportunities to understand how eating motives intersect with attitudes about the environment. In this study, associations were examined between four motivations to eat meat (natural, necessary, normal, and nice), three motivations to be vegetarian (health, the environment, and animal rights), and seven environmental attitudes (knowledge, connectedness to nature, intrinsic, extrinsic and social motives for sustainable behavior, faith in growth, and biospherism) in a community sample from the US (N = 1,234). Distinct profiles of environmental attitude were found across different motivations to eat meat. Ethical motives to be vegetarian were more strongly related to proenvironmental attitudes than health motives. These results move beyond general associations between meat reduction and proenvironmental attitudes by showing that individual differences in dietary motivations have different implications for how individual think about and interact with the environment. Implications for future research are discussed.

Reducing meat consumption is one of the most effective ways individuals can reduce their climate footprint (Chai et al., Citation2019; Dietz et al., Citation2009; Godfray et al., Citation2018). A large body of research shows that people who eat less meat tend to also be more environmentally conscious in other ways (Krizanova et al., Citation2021; Ploll & Stern, Citation2020). However, there is nuance beyond the general belief that it is important to protect the environment and that it is good to eat fewer animal products. In fact, research has identified several different kinds of environmental attitudes and different dietary motivations. Understanding the intersection between the specific features within these two domains could help provide a more nuanced picture of individual differences in proenvironmental behavior. A more detailed picture of how proenvironmental attitudes and dietary motives intersect could, in turn, be used to evaluate the effectiveness of different types of policies and interventions and test hypotheses about personalized approaches to encourage proenvironmental and just behavior. The goal of this exploratory study was to examine how a range of environmental attitudes intersect with dietary motives in a relatively large community sample from the United States.

Environmental attitudes

Proenvironmental attitudes are consistently related to sustainable behaviors (SBs) such as reduced consumption of goods, responsible use of old goods, recycling and responsible waste elimination, use of public transportation, buying local foods, and reducing the consumption of animal products (Bleidorn et al., Citation2021; De Groot & Steg, Citation2010; De Young, Citation1985; Gilg et al., Citation2005; Guagnano et al., Citation1995; Harland et al., Citation1999; Karp, Citation1996; Mayer & Frantz, Citation2004; Pelletier et al., Citation1998). This association suggests that caring about the environment leads to behaviors that tangibly support the environment. Several different kinds of proenvironmental attitudes can be distinguished.

Awareness or knowledge about environmental issues has also been consistently linked to SBs (Zsóka et al., Citation2013). People who are more concerned about the environment are more likely to learn about the threat of climate change and how it can be addressed, and conversely people who learn more about these issues are likely to become more concerned. However, knowledge is different from other attitudes in that it is based on having actively sought and obtained factual information about the topic, rather than one’s feelings or personal opinions.

Connectedness to nature (Mayer & Frantz, Citation2004) is a construct commonly used in the sustainability literature to capture a general proenvironmental orientation. Connectedness to nature has to do with the subjective experience of being a part of nature, and given this connection, a concern for its health and well-being. People who are connected to nature are not only more likely to have a lower ecological footprint (Zylstra et al., Citation2014), meaning that they are less likely to contribute negatively to the climate crisis by overconsuming goods that contribute to land and water usage, they are also more likely spend time in the wilderness for leisure and have richer experiences there (Davis & Gatersleben, Citation2013).

This general disposition is different from specific motivations to engage in proenvironmental behavior. At least three specific proenvironmental motives can be distinguished from one another (Hopwood et al., Citationin press). The first is an intrinsic motive based on the belief that it is important to protect the environment because it is simply the right thing to do. The second is an extrinsic motive for proenvironmental behavior related to gaining rewards and avoiding punishments such as taxes or fines. The third is a social motive related to being approved of by others or avoiding public judgment.

Finally, some environmental attitudes are related to broader political visions about how societies can function to achieve certain outcomes. Faith in growth is the belief that environmental issues will be effectively dealt with if we continue to rely on technology, market economy, and human development (Gilg et al., Citation2005). In contrast, biospherism is the belief that we must all pitch in to protect the environment.

These seven environmental attitudes—knowledge, connectedness to nature, intrinsic, extrinsic and social motives for sustainable behavior, faith in growth, and biospherism—differ from one another in ways that imply different patterns of association with dietary motives, as described in the next section. Examining these patterns of association is the goal of this study.

Dietary motivations

A large body of research has focused on differences between meat eaters and meat reducers on a variety of health, attitudinal, and personality variables (Forestell & Nezlek, Citation2018; Müssig et al., Citation2022; Oussalah et al., Citation2020; Rozin et al., Citation1997). However, recent research suggests that there is considerable variability among meat eaters and veg*ns (vegetarians/vegans) in terms of the reasons they adopt their diets. These differences are important for both basic research and application. Understanding variability in the reasons that people make dietary choices provides novel insights into social cognition as it applies to food, a diverse stimulus that humans interact with on a daily basis. Moreover, dietary choices about eating meat vs. plant-based food often intersect with underlying social, cultural, and moral values, and thus understanding these values offers a window into how such values lead to behaviors and decisions in everyday life. In terms of application, understanding not just that people prefer to eat or not eat meat, but also why they have those preferences, may sharpen efforts to promote certain food choices. Given the advantages of plant-based diets for curbing climate change, understanding how different dietary motives intersect with environmental motives might reveal new insights about how to appeal to individual’s underlying values in order to encourage SBs. Elaborating this intersection is the general goal of this study.

Recent research on dietary motives (Hopwood et al., Citation2022; Hopwood et al., Citation2020; Miki et al., Citation2020; Piazza et al., Citation2020; Rosenfeld & Burrow, Citation2017) has revealed two major findings. First, motives to eat meat are not simply the opposite of motives for a plant-based diet. Instead, people have diverse sets of motives for both domains that do not correspond directly. In fact, in one case—health—people cite the same motive to both eat meat and not eat meat. Second, a relatively limited number of motives account for most of the reasons people give when asked why they eat meat or why they do not. Specifically, four major motives have been identified for eating meat (Piazza et al., Citation2015) and three major motives have been identified for not eating meat (Hopwood et al., Citation2020).

The four most common reasons people give for eating meat is that it is natural (i.e. humans are naturally omnivorous and eating meat is part of the circle of life), normal (it is a common human behavior), necessary (it is important for health), or nice (it tastes good). Piazza et al. (Citation2015) found that more than 80% percent of meat eaters give one of these four reasons as the most important factor in choosing to eat meat. Previous research suggests that each of these “4 Ns” are associated with a different pattern of attitudes, traits, and behaviors (Hopwood & Bleidorn, Citation2019). For instance, the necessary motive is associated with traditional and conservative worldviews, the nice motive with a reduced emphasis on moral concerns, and the natural and normal motives with maladaptive, antisocial personality traits (Hopwood et al., Citation2021a).

All of these variables might be expected to be negatively associated with proenvironmental attitudes, in general. The unique contribution of this study is to examine whether they are related to different kinds of proenvironmental attitudes. For instance, given the association of the necessary motive with conservativism, it might help identify people who tend to believe that market-based solutions will be sufficient for addressing the climate crisis. People who focus on the fact that meat tastes nice might tend to have a more hedonistic worldview and thus think or care relatively less about how their behavior affects the world, and thus may tend to be less connected to nature and more responsive to appeals to increase SBs. In contrast, given that previous research has found that the normal and natural motivations were associated with antisocial personality traits (Hopwood & Bleidorn, Citation2021), these dietary motives might be specifically responsive to extrinsic rewards for sustainable behavior.

The three most common non-religious reasons people give for not eating meat are that plant-based diets are healthy, are good for the environment, or to support animal rights (Fox & Ward, Citation2008; Graça et al., Citation2019; Ruby, Citation2012). These motives have the same structure in people who eat meat as in people who do not (Hopwood et al., Citation2021b). However, as with meat-eating motives, motives for plant-based diet are differentially correlated with certain outcomes (Hopwood et al., Citation2020; Rosenfeld & Burrow, Citation2017; Vainio et al., Citation2016). That being said, the moral motives—environment and animal rights—tend to be strongly correlated with one another and similarly correlated with most external criteria (Hopwood et al., Citation2020). One domain that may be most likely to distinguish plant-based dietary motives is environmental attitudes. In particular, it might be expected that environmental motives for a plant-based diet would be uniquely predictive of other environmental attitudes, given their obvious overlap.

The current study

The goal of this study was to examine relationships between individual differences in dietary motives and environmental attitudes. I examined these associations in three steps in order of increasing rigor and specificity. First, I computed bivariate associations between the four meat-eating motives, three veg*n motives, and seven environmental attitudes. I used confidence intervals to infer differences in associations. Second, I fit regression models with the meat-eating motives and plant-based eating motives as sets to predict each environmental attitude. This allowed me to test whether the motives were related to environmental attitudes controlling for the other motives of their kind (i.e. meat-eating motives controlling for other meat-eating motives). Third, I added political orientation as a covariate to these models. Politically liberal people are more likely to both support climate change policies and engage in SBs than conservatives (Gilg et al., Citation2005; Grob, Citation1995; Hall et al., Citation2018; Hines et al., Citation1987) and to be more motivated to abstain from meat and adopt plant-based diets (Nezlek & Forestell, Citation2020). Political orientation is thus a strong candidate for explaining connections between plant-based dietary motives and environmental attitudes. Any motive-environmental attitude association that was significantly different from 0 and stronger than other motives in all three of these approaches was interpreted as specific and unique.

Methods

Data and materials for this study are available at https://osf.io/q5w8d/?view_only=9de49cc0e5544be7ab11cafae594f653. Participants were 1247 US individuals recruited through the survey platform Prolific. A sample size > 960 provides 80% power to find bivariate correlations > .1. People were removed if they failed more than two attention check items (Marjanovic et al., Citation2014, see OSF) and/or completed the study in < 5 minutes, resulting in a sample size of 1234. Participants were paid $7.50 for participating. The sample were 49.84% women, 48.46% men, and 1.30% non-binary; Mage = 46.27, SDage = 16.05; 56.56% Democrat, 23.09% Republican, 1.86% libertarian, 1.05% green party, 17.34% independent or nonaffiliated.

Measures

The Motivations to Eat Meat Inventory (MEMI; Hopwood et al., Citation2021a) was used to measure Natural (ωh = .81), Normal (ωh = .75), Necessary (ωh = .85), and Nice (ωh = .87) motives for eating meat. The 19 MEMI items are responded on a 7-point Likert scale.

The Vegetarian Motives Inventory (VEMI; 15; Hopwood et al., Citation2020) was used to measure Health (ωh = .90), Environmental (ωh = .89), and Animal Rights (ωh = .88) motives to adopt or consider a plant-based diet. Its 15 items are responded to on a 7-point Likert scale.

Environmental Knowledge was measured with 8 items taken from the Assessment of Sustainability Knowledge survey (Zwickle et al., Citation2014; ωh = .56). Each item asks a factual question with one correct answer; 5 options are given. Scores reflect the number of correct answers.

The Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS; Mayer & Frantz, Citation2004; ωh = .20) is a 14-item measure of one’s feelings towards nature and the environment, with items rated on 5-point Likert scale.

To measure Environmental Motives, a measure of Extrinsic (3 items, ω = .81), Intrinsic (4 items, ωh = .91), and Social (4 items, ωh = .85) motives for sustainable behaviors was created for this study. Items were responded to on a 5-point Likert response scale.

Environmental Values were measured with 10 items from Gilg et al. (Citation2005). These items were separated into Faith in Growth (i.e. the belief that humans should do with nature what they please, 5 items, ωh = .53), and Biospherism (i.e. the belief that the balance of nature should be protected, 5 items, ωh = .69) scales.

The Social and Economic Conservatism Scale (Everett, Citation2013; ωh = .63) is a 12-item measure of liberalism-conservatism with attitudes about different political issues rated on a 0 (liberal) to 100 (conservative) scale.

Analyses

As described above, I used bivariate correlations and regression models to examine associations between dietary motivations and proenvironmental attitudes. I conducted analyses separately for meat-eating motives and plant-based dietary motives. I used a Type 1 error rate of .001 to interpret differences between each isolated effect and 0, and .05 (95% confidence intervals) to interpret differences between dependent bivariate correlations.

Results

I first examined associations between motivations to eat meat and environmental variables. I generally expected negative correlations, given that meat eating is harmful for the environment. Indeed, 30/32 bivariate associations were statistically significant and suggestive of less proenvironmental attitudes (Table ). However, there was also considerable variation, suggesting that certain motivations to eat meat are differentially related to different environmental attitudes. The belief that it is normal to eat meat was distinctly associated with low environmental knowledge, social motivations to behave in an environmentally supportive way. It also had the strongest association with faith in progress. People who believe it is nice to eat meat are relatively disconnected from nature, less intrinsically motivated to engage in climate friendly behavior, and more motivated by extrinsic rewards and punishments. Natural had a similar pattern of associations as nice, and in addition was more strongly negatively related to biospherism. Although the belief that it is necessary to eat meat was consistently and negatively associated with proenvironmental attitudes, it was not distinct in its associations.

Table 1. Associations between motivations to eat meat and environmental attitudes

To further examine these associations, I fit regression models with the four meat eating motivations as independent variables and each environmental attitude as the dependent variable. Results are shown in Table . In several cases, bivariate associations were no longer significant when all meat-eating motivations were included in a single model. This includes natural, necessary, and nice with environmental knowledge, extrinsic motivations, and social motivations, normal and necessary with extrinsic motivations, and necessary and nice with biospherism and faith in progress. To provide an even more rigorous test, I entered political conservatism as a covariate to these models. All but one association from the previous regression models—natural with faith in progress—remained significant. There was also one instance of apparent suppression, in which the association between necessary and connectedness to nature became significant in regression models even though the bivariate was negative and non-significant. I did not regard this as a significant result from the regression models given challenges associated with interpreting suppression effects (Martinez Gutierrez & Cribbie, Citation2021). Based on these correlations, confidence intervals, and weights from regression models with and without the political orientation covariate, I drew general conclusions about which meat eating motives are specifically associated with environmental attitudes (bold values in ).

I next examined associations between motivations for plant-based diet and proenvironmental variables. A fairly clear pattern emerged from the bivariate associations (), with environmental motives having the strongest positive correlation with proenvironmental attitudes, followed closely by animal rights motives. Health motives showed a rather different pattern, with relatively modest associations with most environmental attitudes. Regression models with and without the political orientation covariate largely confirmed this pattern (Table ). I again used bold values to indicate which variables showed unique associations based on all three analytic approaches.

Table 2. Associations between motivations to be veg*n and environmental attitudes

Discussion

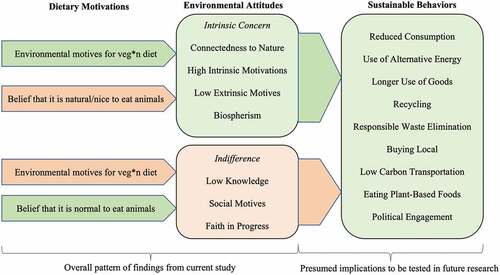

The goal of this study was to go beyond previous research suggesting a general association between plant-based eating and proenvironmental behavior, to examine how specific dietary motives are related to a range of different environmental attitudes. Overall, findings suggested four pathways between dietary motives, environmental attitudes, and potentially SBs (Figure ). Based on the overall pattern of findings, environmental attitudes could be clustered into two groups: those indicating an intrinsic concern about the environment (connectedness to nature, high intrinsic and low extrinsic motives for SBs, and biospherism) and indifference to environmental issues (low knowledge, social motives for SBs, and faith in growth). The strongest and most consistent effects in this study indicated that people with environmental motives for veg*n diet were both intrinsically concerned and not indifferent, whereas the other veg*n motives had less consistent effects. People who think it is natural or nice to eat animals tended to be less intrinsically concerned about the environment, whereas people who think it is normal to eat animals tended to be indifferent to environmental issues. The belief that it is necessary to eat animals was mostly unrelated to environmental motives.

Figure 1. Four potential dietary motivational pathways to increase environmental attitudes and sustainable behaviors

Implications

These findings have both basic and applied implications. In terms of basic research, this study shows that there is considerable nuance beneath the general association with plant-based dieting and sustainable attitudes and behaviors, and that distinguishing and examining specific motives and attitudes helps unwrap informative complexity. Diet is a particularly powerful behavior for two reasons. First, it is very common: people make choices about what to eat every day. Second, it has a variety of implications for the environment (Hertwich, Citation2010) including water loss (Koop & van Leeuwen, Citation2017), air quality (Domingo et al., Citation2021), carbon emissions associated with animal waste and transportation (Vitali et al., Citation2018), and reduced microbial resistance (Espinosa et al., Citation2020). However, dietary choices are driven by several factors, including cost, availability, and values and attitudes (Graça et al., Citation2019). In this study, we focused on attitudes regarding the decision to eat meat or not. Previous research suggests that people typically give one or more of four reasons to eat meat—that it is natural, normal, necessary, or nice—and one or more of three reasons not to eat meat—that plant-based diets are healthy, good for the environment, or to support animal welfare. However, very little research has focused on how these motives differ from one another, and no previous study has examined whether they have distinct profiles of environmental attitudes. Understanding how these different motives for choosing to eat animal products or not can provide new insights into the underlying moral schema that drive moral consumptive behavior in general, including as this applies to the issue of environmental sustainability. Both dietary choices and environmental attitudes are informed by complex social, cultural, and moral values. Thus, elaborating their intersection can provide a richer sense of the patterns of reasoning people have for making different kinds of moral decisions on a day-to-day basis.

Armed with a greater understanding of these patterns, policy makers, educators, and activists may be able to adopt and implement more effective strategies for shaping and encouraging more sustainable and just behavior (Graça et al., Citation2019; Taufik et al., Citation2019). For instance, highlights that people who believe it is nice to eat meat are indifferent to the climate crisis, and previous research indicated that eating meat because it is nice is rooted in hedonism (Hopwood et al., Citation2022). As such, people who endorse this motive might be convinced to eat more plant-based food if that food simply tasted as good as animal products, whereas appeals to change diets to protect the environment may not be as effective. In contrast, the belief that it is normal to eat meat may be somewhat more rooted in political beliefs that elevate other concerns (e.g. employment or ability to grow wealth) above environmental preservation. Economic rewards and punishments may be more useful than appeals about climate change for encouraging people who think it is normal to eat meat to adopt plant-based diets. While these results are too premature to be used to inform specific interventions, future work aimed at identifying people’s underlying reasons for eating animals may assist in developing and using targeted advocacy approaches that can be more effective and efficient than one-size-fits all strategies.

Limitations

Future research should further explore the social cognition related to moral behaviors involving plant-based eating and environmental sustainability and test the implications of these findings for policy, intervention, and advocacy. Studies should also address the limitations to this approach. The first limitation is that these data were cross-sectional. Experience sampling (Nisbet et al., Citation2009), lab task (Lange & Dewitte, Citation2019; Lange et al., Citation2018), passive sensing (Jahn et al., Citation2011), or behavioral observation (Wu et al., Citation2013) designs could be used to approximate attitudes and choices as they play out in real life more closely. Moreover, this study focused on attitudes, but these kinds of designs could also be used to sample actual behavior. Although such methods are costly and labor intensive, establishing the processes by which attitudes, food choices, and actual behavior are connected is critical for establishing mechanisms and moving this kind of work forward. The second limitation was the use of an American sample. Attitudes about the environment and plant-based diets are likely to vary considerably across cultures (Earle & Hodson, Citation2017; Milfont et al., Citation2010). These findings may not replicate in other cultures and future research from different kinds of samples is an important direction for future research. Finally, several attitudes about the environment and motivations for plant-based diet were not assessed in this study (e.g. Rosenfeld & Burrow, Citation2018). Studies with a wider range of variables would help build upon these findings and provide a fuller picture of associations between these domains.

Conclusion

In this study, I tested connections between motivations for eating animal or plant-based diet and environmental attitudes. Results suggested that different reasons to eat meat are associated with different profiles of environmental attitudes. In contrast, and unsurprisingly, environmental reasons to adopt or maintain plant-based diets were the strongest and most consistent correlate of proenvironmental attitudes. These results show that different dietary motives have distinct psychological profiles, establish the importance of connecting different types of moral attitudes to begin understanding the complexity of social cognition underlying moral behavior, and may have implications for policies and interventions designed to reduce climate change and enhance interspecies justice.

Ethical Statement

All participants were consented prior to participation.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges Madeline Lenhausen for her help with data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

This was an exploratory study in existing data that was not preregistered. Data, materials, and script can be found at https://osf.io/5r9ac/?view_only=9de49cc0e5544be7ab11cafae594f653. A previous study with different goals and nonoverlapping analyses has been published with these data (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10668-022-02482-5). None of the analyses in this paper overlap with those of the previous paper.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bleidorn, W., Lenhausen, M. R., & Hopwood, C. J. (2021). Proenvironmental attitudes predict proenvironmental consumer behaviors over time. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 76, 101627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101627

- Chai, B. C., van der Voort, J. R., Grofelnik, K., Eliasdottir, H. G., Klöss, I., & Perez-Cueto, F. J. (2019). Which diet has the least environmental impact on our planet? A systematic review of vegan, vegetarian and omnivorous diets. Sustainability, 11(15), 4110. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154110

- Davis, N., & Gatersleben, B. (2013). Transcendent experiences in wild and manicured settings: The influence of the trait “connectedness to nature”. Ecopsychology, 5(2), 92–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2013.0016

- De Groot, J. I., & Steg, L. (2010). Relationships between value orientations, self-determined motivational types and pro-environmental behavioural intentions. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(4), 368–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.04.002

- De Young, R. (1985). Encouraging environmentally appropriate behavior: The role of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Environmental Systems, 15(4), 281–292. https://doi.org/10.2190/3FWV-4WM0-R6MC-2URB

- Dietz, T., Gardner, G. T., Gilligan, J., Stern, P. C., & Vandenbergh, M. P. (2009). Household actions can provide a behavioral wedge to rapidly reduce US carbon emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(44), 18452–18456. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0908738106

- Domingo, N. G., Balasubramanian, S., Thakrar, S. K., Clark, M. A., Adams, P. J., Marshall, J. D., Muller, N. Z., Pandis, S. N., Polasky, S., Robinson, A. L., Tessum, C. W., Tilman, D., Tschofen, P., & Hill, J. D. (2021). Air quality–related health damages of food. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(20), 20. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2013637118

- Earle, M., & Hodson, G. (2017). What’s your beef with vegetarians? Predicting anti-vegetarian prejudice from pro-beef attitudes across cultures. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 52–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.034

- Espinosa, R., Tago, D., & Treich, N. (2020). Infectious diseases and meat production. Environmental and Resource Economics, 76(4), 1019–1044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-020-00484-3

- Everett, J. A. (2013). The 12 item social and economic conservatism scale (SECS). PloS one, 8(12), e82131.

- Forestell, C. A., & Nezlek, J. B. (2018). Vegetarianism, depression, and the five factor model of personality. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 57(3), 246–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/03670244.2018.1455675

- Fox, N., & Ward, K. (2008). Health, ethics and environment: A qualitative study of vegetarian motivations. Appetite, 50(2–3), 422–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2007.09.007

- Gilg, A., Barr, S., & Ford, N. (2005). Green consumption or sustainable lifestyles? Identifying the sustainable consumer. Futures, 37(6), 481–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2004.10.016

- Godfray, H. C. J., Aveyard, P., Garnett, T., Hall, J. W., Key, T. J., Lorimer, J., Pierrehumbert, R. T., Scarborough, P., Springmann, M., & Jebb, S. A. (2018). Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science, 361(6399), 6399. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aam5324

- Graça, J., Godinho, C. A., & Truninger, M. (2019). Reducing meat consumption and following plant-based diets: Current evidence and future directions to inform integrated transitions. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 91, 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2019.07.046

- Grob, A. (1995). A structural model of environmental attitudes and behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90004-7

- Guagnano, G. A., Stern, P. C., & Dietz, T. (1995). Influences on attitude–behaviour relationships: A natural experiment with curbside recycling. Environment and Behaviour, 27(5), 699–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916595275005

- Hall, M. P., Lewis, N. A.,sJr, & Ellsworth, P. C. (2018). Believing in climate change, but not behaving sustainably: Evidence from a one-year longitudinal study. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 56, 55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.03.001

- Harland, P., Staats, H., & Wilke, H. A. M. (1999). Explaining proenvironmental intention and behaviour by personal norms and the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(12), 2505–2528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00123.x

- Hertwich, E. (2010). Assessing the environmental impacts of consumption and production: Priority products and materials. UNEP/Earthprint.

- Hines, J. M., Hungerford, H. R., & Tomera, A. N. (1987). Analysis and synthesis of research on responsible environmental behaviour: A meta- analysis. Journal of Environmental Education, 18(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1987.9943482

- Hopwood, C. J., & Bleidorn, W. (2019). Psychological profiles of people who justify eating meat as natural, necessary, normal, or nice. Food Quality and Preference, 75, 10–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2019.02.004

- Hopwood, C. J., & Bleidorn, W. (2021). Antisocial personality traits transcend species. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 12(5), 448–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000463

- Hopwood, C. J., Bleidorn, W., Schwaba, T., Chen, S., & Capraro, V. (2020). Health, environmental, and animal rights motives for vegetarian eating. PloS One, 15(4), e0230609. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230609

- Hopwood, C. J., Lenhausen, M. R., & Bleidorn, W. (2022). Toward a comprehensive dimensional model of sustainable behaviors. Environment, Development, and Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02482-5

- Hopwood, C. J., Lenhausen, M. R., & Bleidorn, W. (inpress). Toward a comprehensive dimensional model of sustainable behaviors. Environment, Development and Sustainability.

- Hopwood, C. J., Piazza, J., Chen, S., & Bleidorn, W. (2021a). Development and validation of the motivations to Eat Meat Inventory. Appetite, 163, 105210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105210

- Hopwood, C. J., Rosenfeld, D., Chen, S., & Bleidorn, W. (2021b). An investigation of plant-based dietary motives among vegetarians and omnivores. Collabra: Psychology, 7, 1. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.19010

- Jahn, M., Schwartz, T., Simon, J., & Jentsch, M. (2011). Energypulse: Tracking sustainable behavior in office environments. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Energy-Efficient Computing and Networking, 87–96.

- Karp, D. G. (1996). Values and their effect on pro-environmental behavior. Environment and Behavior, 28(1), 111–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916596281006

- Koop, S. H., & van Leeuwen, C. J. (2017). The challenges of water, waste and climate change in cities. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 19(2), 385–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-016-9760-4

- Krizanova, J., Rosenfeld, D. L., Tomiyama, A. J., & Guardiola, J. (2021). Pro-environmental behavior predicts adherence to plant-based diets. Appetite, 163, 105243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105243

- Lange, F., & Dewitte, S. (2019). Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 63, 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.04.009

- Lange, F., Steinke, A., & Dewitte, S. (2018). The pro-environmental behavior task: A laboratory measure of actual pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 56, 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2018.02.007

- Marjanovic, Z., Struthers, C. W., Cribbie, R., & Greenglass, E. R. (2014). The conscientious responders scale: A new tool for discriminating between conscientious and random responders. Sage Open, 4(3), 2158244014545964. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014545964

- Martinez Gutierrez, N., & Cribbie, R. (2021). Incidence and interpretation of statistical suppression in psychological research. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne Des Sciences du Comportement, 53(4), 480–488. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000267

- Mayer, F. S., & Frantz, C. M. (2004). The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(4), 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.10.001

- Miki, A. J., Livingston, K. A., Karlsen, M. C., Folta, S. C., & McKeown, N. M. (2020). Using evidence mapping to examine motivations for following plant-based diets. Current Developments in Nutrition, 4, nzaa013. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzaa013

- Milfont, T. L., Duckitt, J., & Wagner, C. (2010). The higher order structure of environmental attitudes: A cross-cultural examination. Revista Interamericana de Psicología/Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 44(2), 263–273. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=28420641007

- Müssig, M., Pfeiler, T. M., Egloff, B., & Wagner, G. G. (2022). Minor and inconsistent differences in big five personality traits between vegetarians and vegans. PloS One, 17(6), e0268896. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0268896

- Nezlek, J. B., & Forestell, C. A. (2020). Vegetarianism as a social identity. Current Opinion in Food Science, 33, 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2019.12.005

- Nisbet, E. K., Zelenski, J. M., & Murphy, S. A. (2009). The nature relatedness scale: Linking individuals’ connection with nature to environmental concern and behavior. Environment and Behavior, 41(5), 715–774. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508318748

- Oussalah, A., Levy, J., Berthezène, C., Alpers, D. H., & Guéant, J. L. (2020). Health outcomes associated with vegetarian diets: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Clinical Nutrition, 39(11), 3283–3307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2020.02.037

- Pelletier, L. G., Tuson, K. M., Green-Demers, I., Noels, K., & Beaton, A. M. (1998). Why are you doing things for the environment? The motivation toward the environment scale (mtes) 1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(5), 437–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01714.x

- Piazza, J. R., Cooper, L., & Slater-Johnson, S. (2020). Rationalizing the many uses of animals: Application of the 4N justifications beyond meat. Human-Animal Interaction Bulletin, 8, 1–22. https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/130548

- Piazza, J., Ruby, M. B., Loughnan, S., Luong, M., Kulik, J., Watkins, H. M., & Seigerman, M. (2015). Rationalizing meat consumption. The 4Ns. Appetite, 91, 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.011

- Ploll, U., & Stern, T. (2020). From diet to behaviour: Exploring environmental-and animal-conscious behaviour among Austrian vegetarians and vegans. British Food Journal, 122(11), 3249–3265. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-06-2019-0418

- Rosenfeld, D. L., & Burrow, A. L. (2017). Vegetarian on purpose: Understanding the motivations of plant-based dieters. Appetite, 116, 456–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.05.039

- Rosenfeld, D. L., & Burrow, A. L. (2018). Development and validation of the dietarian identity questionnaire: Assessing self-perceptions of animal-product consumption. Appetite, 127, 182–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.05.003

- Rozin, P., Markwith, M., & Stoess, C. (1997). Moralization and becoming a vegetarian: The transformation of preferences into values and the recruitment of disgust. Psychological Science, 8(2), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1997.tb00685.x

- Ruby, M. B. (2012). Vegetarianism. A blossoming field of study. Appetite, 58(1), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.09.019

- Taufik, D., Verain, M. C., Bouwman, E. P., & Reinders, M. J. (2019). Determinants of real-life behavioural interventions to stimulate more plant-based and less animal-based diets: A systematic review. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 93, 281–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2019.09.019

- Vainio, A., Niva, M., Jallinoja, P., & Latvala, T. (2016). From beef to beans: Eating motives and the replacement of animal proteins with plant proteins among Finnish consumers. Appetite, 106, 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.03.002

- Vitali, A., Grossi, G., Martino, G., Bernabucci, U., Nardone, A., & Lacetera, N. (2018). Carbon footprint of organic beef meat from farm to fork: A case study of short supply chain. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 98(14), 5518–5524. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.9098

- Wu, D. W. L., DiGiacomo, A., Kingstone, A., & Sinigaglia, C. (2013). A sustainable building promotes pro-environmental behavior: An observational study on food disposal. PloS One, 8(1), e53856. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0053856

- Zsóka, Á., Szerényi, Z. M., Széchy, A., & Kocsis, T. (2013). Greening due to environmental education? Environmental knowledge, attitudes, consumer behavior and everyday pro-environmental activities of Hungarian high school and university students. Journal of Cleaner Production, 48, 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.11.030

- Zwickle, A., Koontz, T. M., Slagle, K. M., & Bruskotter, J. T. (2014). Assessing sustainability knowledge of a student population: Developing a tool to measure knowledge in the environmental, economic and social domains. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education.

- Zylstra, M. J., Knight, A. T., Esler, K. J., & Le Grange, L. L. (2014). Connectedness as a core conservation concern: An interdisciplinary review of theory and a call for practice. Springer Science Reviews, 2(1–2), 119–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40362-014-0021-3