ABSTRACT

Climate change is one of the most pressing issues among the current environmental problems and it affects the livelihood of the community by creating scarcity of renewable resources. Ethiopia is one of the countries in Sub-Saharan Africa extremely vulnerable to climate change. This study was aimed to investigate climate-change-driven conflict by taking case from Northeast Ethiopia. A cross-sectional survey study was employed and data was collected from the primary and secondary sources. The structured household survey, key informant interviews and focus group discussions were used to collect data from selected samples. About 100 survey respondents, 10 KII and 3 FGD participants were involved in generating data which was analyzed by employing descriptive and qualitative analysis techniques. The finding revealed that climate change is occurring through increasing temperature and decreasing rainfall and frequent drought caused by deforestation, degradation of natural resources and urbanization. Consequently, the participants have experienced critical shortage of water, animal fed and most of them were food insecure. Similarly, a considerable number of residents were exposed to climate-change-induced conflict. The conflict in North Wollo was climate driven and interethnic whereby Amhara ethnic are conflicting with Afar ethnic over the resources around their border. It is recommended that employing the customary law and religious institutions are the most trusted and leading agents to resolve conflict. Area-specific and local-based climate change adaptation techniques including drought-resistant plant species and reducing the number of livestock were suggested as the solutions to solve the problems.

1. Introduction

Climate change is an international agenda and its impact is felt at global, continental and national levels. It is also leading into destruction of crops, severe wildfire, death of herds and flooding, loss of life of millions and making the existing conventional life styles unrealistic. Climate change is also causing mobility by making certain parts of the world much less viable place to live (Brown, Citation2008; Stapleton et al., Citation2017). Evidences also show that tens of millions of people are likely to be displaced over the next two to three decades due to climatic factors (White-House, Citation2021). The climatic alteration is going to exacerbate impact on the world economy in the future and the livelihood conditions of the people (Milán-García et al., Citation2021). Climate change will increase the potential violent conflict (Smith & Vivekananda, Citation2007) by intensifying the risk of conflict to increase. Worsening and undermined livelihood conditions contribute to escalating grievances. Particularly, for those groups directly dependent on natural resources, climate change minimizes livelihood alternatives (Stephen et al., Citation2019). Consequently, leading to increased competition and fight to capture resources and contribute to growing tension and conflict (Fishman & Li, Citation2022).

Climate hazards such as drought appear to have long-term stresses than short-term events, such as flooding, to lead to conflict (Koubi, Citation2019). Climate-change-induced conflict and displacement of people in Ethiopia is becoming more evident. Drought frequency is increasing with climate change in Ethiopia and causing severe damage. The rising temperature because of drought caused habitat fragmentation, soil erosion, damage to plants, animals and loss of biodiversity affects air and water quality (Woodward et al., Citation2010). Drought is a major shock for households depending on agriculture, potentially undermining local livelihoods and well-being. For instance, drought in Ethiopia in 2015 is claimed to be one of the worst climate change events, the country experienced in more than 50 years. Rainfall deficits up to 50% below average have caused severe crop failures, especially in northeastern parts of the country, with one out of ten Ethiopians becoming food insecure (Kassegn et al., Citation2021). The impact of climate change in the form of drought is traced back long period ago (Table ).

Table 1. Major drought incidences in Ethiopia

However, studies on further understanding of climate-change-driven conflict and tracing security concerns and accompanied consequences or risks such as socio-economic insecurity, economic weakness, food insecurity and large-scale displacement and other related issues is limited in Ethiopia. Therefore, it is very crucial to conduct research on this timely theme and produce policy paper having future looking options for addressing climate-change-induced conflict and security in the context of Ethiopia. Despite the growing recognition on the impact of climate change on conflict and accompanied worsening livelihood situation and increasing trend of displacement, empirical evidences showing the linkage between climate change and conflict is limited in Ethiopia. More specifically in the context of Ethiopia again, little is known about how policy and legal frameworks are responsive to conflicts and displacements induced by climate, particularly by the recurring drought. Hence, developing policies and frameworks that respond to the existing challenges and realities on the ground, demand proper understanding of the contexts. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to explore and understand the linkage between climate change and conflict in the context of Ethiopia and contribute to the existing theoretical and empirical evidences.

2. Nexus between climate change and conflict

The rate of earth’s climate change has increased rapidly in an unprecedented manner in recent past years, making the world much warmer. Human activities such as burning fossil fuels, like natural gas, oil, and coal which lead to releases of greenhouse gases into earth’s atmosphere. Consequently, climate change, is affecting frequency and intensity of drought, heat waves, extreme weather events and rising sea levels pose significant threats to people’s livelihood, health and well-being (Ruwanza et al., Citation2022). Climate change is impacting the availability of natural resources and intensifying food insecurity. It leads to decreased agricultural yields, unsuitability of grazing grounds, drying of water bodies and emulates displacement and conflict over the resource scarcity. Climate change also intensifies already stressed conditions and weak political institutions and becomes an additional obstacle to economic growth, development, and political stability (Mekonen & Berlie, Citation2021).

According to certain studies, climate-change-based conflict, can be violent behaviors between persons and interpersonal groups. Interpersonal conflicts may lead to crime acts such as murder, assault, rape, and robbery (Mera, Citation2018). In a conflict situation, resource scarcity may push fighting groups to try and maximize their gains through battle, discouraging them from negotiating peacefully for a shared allotment of a shrinking resource. Climate-change-based resource scarcity threatens the ability of peacemakers to convince warring groups (Hoffmann, Citation2022). Empirical evidences also show that there are a number of instances, of water resources based conflicts. For instance, because of drought across and within borders, conflicts over access to water among herdsmen and farmers near the Kenyan-Ethiopian border; Ethiopian and Somali nomads is a commonly seen phenomenon (Mulugeta, Citation2011). There is a dispute between Malian shepherds and Mauritanian horsemen over the control of water bore holes. These challenges are most pronounced in fragile states already grappling with weak governance, high rates of poverty and income inequality. The intensification of climate change likely may further escalate conflict risks, exacerbating threats to peace and stability.

2.1. Pathways to link climate change and conflict

The concept of ‘pathways’ is an important tool for policymakers to traverse the complicated relationships between climate change, peace and security and to influence their decision-making in conflict-affected and climate-vulnerable regions (Mobjörk et al., Citation2020). According to Koubi (Citation2019), there exist two major and potential pathways, direct and indirect pathways. The direct pathways view climate change as a factor affecting the likelihood of conflict via direct physiological and psychological factors and resource scarcity. The second postulates that climate indirectly leads to conflict by reducing economic output and agricultural incomes, raising food prices, and increasing migration flows. Whether climate directly or indirectly affects conflict, however, depends on socioeconomic and political factors that condition (intensify or weaken) the effect.

2.1.1. Direct pathways to link climate change with conflict

The direct pathways to climate change are mainly connected to physiological and psychological factors driven by climate change that also affects the likelihood of interpersonal relationship (Koubi, Citation2019). For instance, warmer or colder temperature usually elevate the level of discomfort and aggressiveness, increase hostility and violence (Anderson, Citation2001). Increasing discomfort and hostility may lead to large-scale displacements thereby generating conflicts in receiving areas (Warnecke et al., Citation2010). Studies also show that climate change affects the likelihood of intragroup violence via the scarcity of renewable resources such as freshwater, arable land, forests, and fisheries (Froese & Schilling, Citation2019). Following a neo-Malthusian line of argument, it is assumed that adverse climatic conditions, for example, high temperature or low rainfall, coupled with overpopulation reduce the resources needed to sustain human livelihood. Reduced resources increase competition, which leads to conflict (Froese & Schilling, Citation2019; Koubi, Citation2019). At the national level, for instance, less rainfall or high temperature could lead to conflict among consumers of water, for example, farmers and herders, as well as urban unrest, insurrections, and other forms of civil violence, especially in the developing world. Similarly, climate change can also led to frequent and severe extreme weather events (droughts, floods, heat waves, etc.), which, in turn, reduce agricultural production and productivity, increase water scarcity, the incidence of pests and diseases, human migration, and conflict. The driest period can also greatly increase risks of violence and conflict over increasingly scarce resources such as freshwater and arable land (Zegeye, Citation2018).

Scarcity of shared resources such as trans-boundary water resources, grazing land, resulted less rain fail or high temperature or drought can lead to interstate conflicts. Scholars in the field of political ecology have also identified other factors such as poor governance, corruption, institutional instability and other location-specific and structural conditions as important confounding factors in the relationship between resource scarcity and conflict (Maxwell & Reuveny, Citation2000). Hence, the mismanagement of land and natural resources is contributing to new conflicts and obstructing the peaceful resolution of existing ones in the era of increasing competition over diminishing renewable resources, such as land and water. This is being further aggravated by environmental degradation, population growth and climate change. Thus, climate change influences conflict dynamics via a complex interplay of intermediary variables.

2.1.2. Indirect pathways

Climate change can be viewed broadly as an indirect source of conflict, a threat or risk multiplier that amplifies existing economic, social, and political risk. As indirect drivers or pathways, socioeconomic conditions, governance, and political considerations all play important roles in translating climate change into conflict risks. Food security, water security, migration, and mobility are the key interconnected indirect pathways that translate climate change into conflict (Mobjörk et al., Citation2020). The indirect path ways to demonstrate the linkage between short and long-term environmental changes associated to climate change are interrelated that include: (a) livelihoods, (b) migration and mobility, (c) armed group tactics and (d) elite exploitation. The negative consequences of climate change on livelihoods can increase the possibility of conflict, and conflict again can exacerbated worsening livelihood situations. The deterioration of the livelihood condition further marginalizes impacted populations and contributes to the escalation of grievances and conflicts. It is self-evident that a lack of economic options increases the possibility that individuals may resort to violence to protect themselves or get access to decreasing resources.

Migration is being widely recognized as an adaptation strategy for people whose livelihood or survival are threatened by the effects of climate change (Parrish et al., Citation2020). It is clear that unexpected disasters may lead to movement or displacement people from one place to the other for survival (Parrish et al., Citation2020). Hence, climate change as a natural disaster may influence migratory movement towards areas with better livelihood options. Population movements induced by climate change can increase the risk of community-based violence and conflict by bringing migrants into confrontation with locals or other migrant groups. Resource scarcity in the receiving area and competition for it is one important argument for why this pathway to be connected with conflict. Empirical evidences also show that climate change can influence armed groups’ strategic decisions and tactics in various ways in order to strengthen the armed groups and obtain access to natural resources, particularly in productive territories and during times of scarcity. Elites may exploit vulnerable groups or communities and mismanage resources, escalating conflict (Mobjörk et al., Citation2020). According to FAO (Citation2015), climate change creates severe security threats, notably in terms of water and food security in fragile states, and neglecting these risks would have a growing impact on human lives and livelihoods, economic growth and peace and security in the locality.

2.2. Typologies of climate-change-induced conflicts—pathologies

The indirect relationship between climate change and increased conflict is acknowledged in academic and policymaking communities. It is largely explained that climate change is a threat multiplier’ that aggravates existing political or socio-economic problems. Significant number of studies have clearly recognized climate change as a threat or pathogen, promoting risk in many already fragile societies (Froese & Schilling, Citation2019; Sweijs et al., Citation2022). Climate-related conflict pathology is thus defined as the unique mechanisms by which the interplay of climate change and social, economic and political factors leads to conflict. Attempts are also made to categorize climate-induced conflicts (Sweijs et al., Citation2022). In accordance with the above argument, seven types of climate-related conflicts are outlined (Table ).

Table 2. Typologies of climate-change-induced conflict

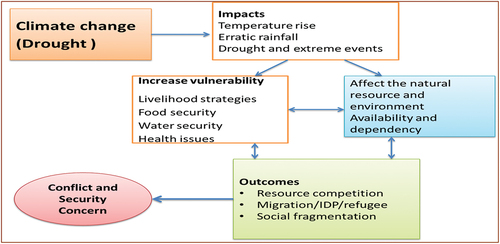

2.3. Conceptual framework of the study

The existence of direct and indirect relationship between climate change and the increased likelihood of conflict and security concern is clearly acknowledged in academic and policy formulating communities and surfaced widely in media and public discourse. However, understanding the specific causal relationship remains underexplored and speculative. Therefore, it is important to understand how, and under what circumstances that climatological factor particularly drought interact with social, political, and economic factors to induce violent conflict. Hence, the conceptual framework of this study is built on socio-economic and political pathways linking climate change to conflict (see ). Climate change pose a serious security threat by worsening poverty and desperation and imposing involuntary migration, competition with other communities over scarce resources. Climate change is directly and indirectly linked to conflict and violence within the community by exacerbating existing social, economic and environmental factors. Climate change also increase frequency of droughts and floods lead to food, and water, health insecurity and scarcity to natural resource availability and high risk livelihood vulnerability. It may also worsen environmental conditions and force people to migrate in large masses, thereby increasing environmental stress in the receiving area and increase the potential for radicalization and ethnic hatreds. In Ethiopia, since the majority of the population directly dependent on natural resources for its livelihood, the predicted impacts of climate change for resource availability and food security in the country could be dramatic. Consequently, climate-change-induced migration, competition over natural resources and other coping responses of households and communities could increase the risk of domestic conflict and have international repercussions. Climate change, increase competition over the scarcity of renewable resources in subsistence-economy societies may cause unemployment, loss of livelihood, and loss of economic activity and this, in turn, decrease state income and make the population more vulnerable to conflict and displacement.

3. Research methods

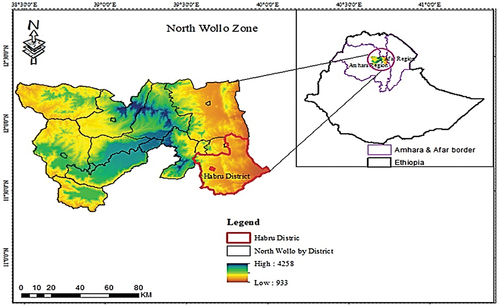

3.1. Study area context

Ethiopia has total area of over 1 million km2 with a population of 120 million and the second most populous country in Africa (CSA, Citation2021). Approximately, 85 percent of the population lives in the rural areas. Ethiopia’s economy is dependent on agriculture, which accounts for 40 percent of the GDP, 80 percent of exports, and employ an estimated 75 percent of the country’s workforce. North Wollo is one of thirteen zones in Amhara National Regional State (ANRS). The zone has an estimated area of 12,179.6 km2, which covers about 20% of the Amhara Regional State (Gebre et al., Citation2017). Most part of zone is dry, semiarid and repeatedly hit by recurrent drought and famine instigated by the changing climate and continuous resource degradation. The elevation of the zone ranges from 913 to 4187 masl (). It has four agro-ecological zones: lowland (Kolla), mid-latitude (Woina-Dega), highland (Dega) and wurch covering 38%, 34%, 21% and 7% of the zone, respectively (Simachew et al., Citation2022). The zone has bi-modal and short rainy season from February to April and long rainy season from June to September (Aragie & Genanu, Citation2017). However, rainfall is erratic and highly variable in the zone. North Wollo also receives a maximum total annual rainfall of 1057.9 mm in the highland areas and as low as (633.9 mm) in the drier parts of zone. The average annual mean temperature of the study area ranges from 20.6° to 30.4°. North Wollo has total population of 1,824,361, (913,572 males and 910,789 females) (CSA, Citation2021). More than 85.2% of the population lives in rural areas. The majority of population depended on mixed farming, including crop production and livestock herding. The major crops grown in the zone include barley, sorghum, teff, maize, and wheat. Habru District is one of 14 districts in North Wollo zone. According to CSA (Citation2021), the total population of district was 235,347, (118,088 male and 117,259 females; CSA, Citation2021).

3.2. Research design

A cross-sectional research design were used to collect data for this study from both primary and secondary data sources. The study applied both the multistage and purpose sampling method to select the district, kebeles, and household heads, starting from the general (areas having the same agro-ecological zone) to the most specific level (households).

The process of the study passed planning, reviewing literature and screening variables stage; developing data gathering tool and conduct survey stage and; synthesis, explanation and presentation of result stages. The study employed qualitative and quantitative data from primary and secondary sources. The study reviewed and conceptualized the impact of climate change on conflict from empirical evidences including legal and policy frameworks and development programs. Primary data was collected by using questionnaire survey, key informant interview and focus group discussion from stakeholders such as security, agriculture and natural, disaster and risk, environmental authority, low land and irrigation development, zonal and district administration, agro-postural development officials and experts, local communities and NGO participants. The secondary data was also collected from theoretical and empirical literature about climate change impacts, conflict and displacement.

3.3. Data collection tools

Questionnaire Survey: A questionnaire survey was administered by developing a structured questionnaire to obtain quantitative and qualitative information from the officials and experts of zone and district, local community and other stakeholders. These tools are expected to catch the ideas of officials, experts, the local communities’ and other stakeholders’ about perception, attitude and awareness on climate change impact and socio-economic issues. The questionnaire was also designed to address the issue of livelihood vulnerability including food insecurity and displacement that lead to conflict. For questionnaire survey, the study selected 100 sample participants randomly from the local community.

Key Informant Interview (KII): KII fieldwork begins by speaking with key informants who know about the study topic in question. A diverse group of people with specific knowledge on climate change and security issues including higher officials and high-level experts in the sample site were conducted. In addition, researchers and people working in climate change, security, environment, drought, displacement and conflict, community-based organizations (CBOs), and non- Government organizations (NGOs) workers were among the people who were interviewed. Totally, about 10 KII were conducted to include ideas, which are not captured by other data collection tools to enhance the data quality of the study.

Focus Group Discussion (FGD): FGD is one of the most widely valuable data collection methods in qualitative research. For this research, FGD is essential to gather primary data that might not be collected by other data collection tools, such as KII and questionnaire. By the support of local leaders, focus group discussants were selected by considering their education level, age, gender, income, residence, position, participation, or non-participation in a given program or intervention. This method helped the study to get into direct contact with participants and generate data by recording what they say and observing their feelings and the real atmosphere. Two FGD groups having twelve members with different background were conducted. These were, One FGD group with zonal and district experts and the last one with local communities including local leaders/elders/farmers in selected villages.

Non-participatory observation: Observation involves the active acquisition of information from primary sources. The investigators have developed the checklists and observed the situation in the study site while collecting other data that supported the study to make judgments about what they know about the outcomes. They offer systematic ways of collecting data about specific behaviors, knowledge and skills. Hence, direct observation is applied for collecting evaluative information. These tools are essential to generate missed data by the other methods and to make triangulation among themselves.

Secondary data sources: Document investigation is an efficient strategy for inspecting or assessing archives. Secondary data was collected by reviewing various research publications, government policy, strategy and project documents of various organizations and institutions working on the subjects under investigation.

3.4. Sampling techniques & sample size

In this study, a purposive and random sampling techniques were employed to select sample households and experts from the study site. The selection of the study site was purposive based on the severity of impact of climate change. Hence, systematic identification of hot spot areas related to climate change, displacement and conflict was held to have appropriate data from the purposively and randomly selected samples from North Wollo zone. Similarly, to include the local communities saying on the research, Habru District was selected based on its severity by the recurrent drought and climate change. After identifying the zone and district, first contact has been made with two experts from disaster and risk and land administration offices. Through the support of these experts’ other additional four experts were selected and one day training was given to the experts about data collection, how to approach the households and experts and on how to administer questionnaire. The selection of enumerators was based on their familiarity with local culture and language and their previous experience of similar data collection. Finally, data was collected from security, agriculture and natural resource management, disaster and risk, environmental authority, low land and irrigation development, administration, agro-postural development, labor and social affairs, women and youth officials and experts and NGO participants. About 40 percent of the survey questions were filled by these purposively and randomly selected officials and experts at zone and district by the support of trained enumerators. Similarly, the remaining 60 percent of questionnaire were filled by purposively and randomly selected rural households from selected kebeles (smaller administrative units) by the use of above trained local experts. The contacts of rural households were made by using religious days and farm center meetings and house to house surveys.

3.5. Data analysis

The study employed the thematic analysis technique to identify, analyze, and interpret patterns of events in qualitative data and employing MAXQDA software version 2020 (VERBI, Citation2023). Thematic analysis supports the research in identifying patterns and ‘themes in the study. Finally, systematically understanding of climate change, conflict and security by combining the primary data with reviewing the existing literature available on the nexus between climate change and conflict and security was analyzed.

4. Result and discussion

4.1. Socio‑economic characteristics of sample respondents

Majority (82%) of the respondents were male and the rest (18%) were female (Table ). The number of men household heads is higher than women household heads. The age was categorized into three major age groups (youth, middle and old ages) with middle age group comprised of 57%, is larger than other age groups followed by 38% old age group. This could have a positive relationship with given the fact that as age goes up, knowledge and concern about the climate change and drought conditions overtime increases. The proportion of Muslim followers with 68% is larger than the proportion of Orthodox Christian which was 32% in the study site. Regarding marital status, the proportion of married respondents outweighed the others. The proportion of married respondents was 89%, while the widowed, single, and divorced accounted for 3%, 6% and 2%, respectively (Table ). Regarding the education level, no education of respondents was significantly high (38%) of the total. This could have a negative impact on understanding the climate change and its impact properly, if the community attained education and have good knowledge about climate change and vice versa. However, significant 40% have had tertiary education and the responses of no education group can be balanced. Mixed farming is the main economic activity in which the majority (57%) of respondents obtained their livelihoods (Table ). Some (43%) of the respondents were engaged only on crop production, while a few (3.3%) of them reared only livestock to earn their livelihood.

Table 3. Demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the respondents

4.2. Perception of climate change

In this section of the study, attempt has been made to assess frequency, awareness and perception of the local community about climate change. In the study, about 72% of the survey participants perceived that there is climate change (Table ). Similarly, about 71% and 18% of the participants also expressed that there is increasing and fluctuating temperature overtime, respectively, and about 74% and 16% of respondents also believed that there is decreasing and fluctuating rainfall in their locality (Table ). This shows that in the study site, there are climate change symptoms.

Table 4. Perception of the respondent to climate change and indicators for the past 20–30 years

Furthermore, KII and FGD participants in North Wollo particularly in Habru district, bordering with Afar regional state confirmed that they were frequently affected by climate change. They also shared their views that the volume of rainfall in the area is declining year after year. As a result shortage and fluctuating of rainfall is becoming a common phenomenon in the area. Key informants as witnessed above have confirmed that particularly after 1977, drought has been frequently recurring in the area and desertification has been expanding even in the highland areas. They also shared their opinion that rainy season in the area usually starts very late and end early. Consequently, delayed start of rainy season, short duration and torrential rainfall is commonly seen phenomenon in the area. They also expressed that accidental flooding due to short duration and torrential rainfall is a commonly seen and temperature level is also increasing. They also expressed that many areas of North Wollo and Habru District are known in their frequent and most devastating drought has been occurred in the years 1972 and 1981. Although the KII participants could not exactly state years of drought recurrence, most of them agreed that drought previously has been seen in every ten years’ time interval. However, they confirmed that in most recent times, the frequency and intensity of drought is increasing related to climate change. They also shared their views that drought has been recurring within 3–4 years. They also shared their views that drought in the study site is expanding to more areas covering or affecting an increasing number of districts including Habru.

Key informants and FGD participants have also confirmed that the awareness level of the local community about climate change is very low. They expressed that the local community largely associate drought as God’s punishment for their sin. The awareness and perception about climate change and associated impacts is also very low even by those educated segments of the community. Particularly, during the months of January to July, shortage of water is most prevalent in most parts of the study areas mainly in the Afar side of the study area. As a result, it will be followed by shortage of animal fed. As a result, the Afar community as a coping strategy moves with a huge number of livestock including cows, oxen, camels and goats to the areas used and possessed by Amhara community. Hence, related to climate change and recurrent drought, the local people’s livelihood is challenged and conflict is intensified. Similar to this finding, a number of studies conducted at different part of Ethiopia (Bogale & Zelalem, Citation2022; Mekonen & Berlie, Citation2021) also pointed out that majority of the local people perceived the occurrence of climate change in their respective locality.

4.3. Causes of climate change

In this study, the respondents were asked their perception about causes of climate change and about 33% of the participants stated that deforestation is the main factor of climate change in their locality (Table ).

Table 5. Possible causes of climate change mentioned by respondents

According to participants, deforestation is a common phenomenon because trees are cut for construction, fuel and charcoal production purposes. Similarly, rapid population growth and recent rapid urbanization were also mentioned as the second and third factors for climate change in the study site with (15%) and (14%), respectively (see Table ).The rapid population growth and urbanization demand more food, energy and construction woods there by create pressure on open land vegetation. This shows that local factors can contribute to climate change in the study site. Furthermore, many research findings also testified that land use land cover dynamics (LULC), deforestation and agricultural expansion are the major causes for the increasing trends of temperature and decreasing trend of rainfall over the driest parts of Ethiopia (Mulugeta, Citation2011; Wolteji et al., Citation2022). In addition, in northern and central parts of Ethiopia, rapid population pressure and inappropriate farming method (Cherinet, Citation2019) were some of the direct and indirect cause for the occurrence of climate change in Ethiopia.

Similarly, key informants and FGD participated indicated that climate change in the study area is caused by continuous reduction of forest cover as well as overgrazing. The key informants and FGD participants from the local community who stayed for long time have witnessed the existence of frequently occurring drought in the area. Moreover, according to experts involved in the key informant interview the forest belt was allocated to investors interested in agricultural investment. They cut the forest and converted forest belt into farm land. As a result, land degradation, deforestation and the expansion of desertification are considered as major causes for the climate change in their localities. Particularly, overgrazing by the pastoral Afar community has been aggravating land degradation in the area. Key informants have also shared their opinion that low level awareness of the local community about the relationship between local actions and its impact on the local natural resources situation is another triggering factor for the frequent drought occurrence in the area.

4.4. Impacts of climate change

In the study site, majority (68%) of the participants of the survey study indicated that they were food insecure because of recurrent drought. It was only 22% of the participants who confirmed that they have no food security problem and only 16% of the participants ‘don’t know’ their status (Table ).

Table 6. Impact of climate change on food security

This shows that climate change has made the poor, who were dependent on climate sensitive activities, more vulnerable to food insecurity and unsustainability of livelihood. Studies indicated that climate change, in the semi-dry areas, is anticipated to rise temperature where temperatures already are high, leading to high evaporation losses which will impact on sectors like agriculture (Mertz et al., Citation2009). Climate change also alter local disease pattern, negatively affect agricultural production, consequently and affect the sustainability of livelihoods and poverty levels of the local community.

Similarly, KII and FGD participants expressed that local communities in the study area, are more vulnerable to climate change. The impact is also severe for smallholders’ farmers and the pastoral livelihood system in the arid and semiarid lowlands. The results have manifested in reduction of livestock productivity, crop failure, food insecurity, increased movements of people and conflicts over scarce resources in the area since their livelihood depends on agriculture and semi agricultural activities (Stephen et al., Citation2019). According to the views of key informants, competition to control grazing lands and water has been intensifying between the border communities. Most often, competition to control grazing land and water springs followed by clashes or disagreement among the cattle keepers. The prevalence of competition for grazing land induced by climate change is also confirmed by local community representatives participated in the FGD. Conflicts between the two groups of communities also occasionally result in cattle looting and displacement of local people. The Afar pastoralists continue to push and invade the highlands of the Amhara community in search of water and grazing land for their cattle as drought continue to persist in the area. In the same way, from Amhara region, Amhara people move to Afar by crossing the boundary for the research of grazing and water during the wet season from July to October. In wet season, Amhara people cultivated their farmland and most of their area is covered by crops. During this season, the Amhara from Habru and other districts move to Afar in search of animal fed. The research report made by Stephen et al. (Citation2019) asserted that drought-related farmer-herder conflicts and water tensions have become common and widespread in the Sahel and East Africa countries including Ethiopia.

According to key informants, crop failure because of lack of moisture and adequate animal feeds are common problems in the area. Both pastoralists and semi pastoralists have reduced size of animals because of lack of grazing and water for their livestock. Frequently occurring drought in the area is affecting animals, crop productivity and water supply and the livelihood of the community. Lack of animal feed and scarcity of the resource in area is becoming the sources of conflict between the Afar and Amhara ethnic groups. The conflict is intensified related to lack of water and grazing land. Similarly, Araro et al. (Citation2020) also found that droughts and extreme heat events damage grazing land and reduce yields of crops, causing higher livestock mortality and lower income from livestock sales, which, in turn, depress household incomes and lead to food insecurity or conflict over the scare resources.

Similarly, climate change is creating conducive environment for invasive new species of crop pests and invasive vegetation. Crop pests such as locusts and others are also rapidly invading crops and indigenous vegetation in the study site. The animal diseases such anthrax, blackleg and others are also affecting the health of animals related to climate change. Climate change is affecting the food security and pushing people to displace to nearby urban areas including Addis Ababa and Arab countries in most cases illegally. In the same way, dozens of empirical evidences also witnessed that climate change has an immense negative impact on agricultural activities, particularly on crop and animal production (Gezie & Tejada Moral, Citation2019; Kwakwa et al., Citation2022). This is common on local community solely depends on rain fed agriculture for subsistence and livelihood.

4.5. Adaptation mechanisms of climate change

Efforts have been made by the local community in the study site to minimize and cope up the impacts of climate change. Regarding to this, the participants from the study site have listed some of the adaptation techniques proposed and partly implemented in their localities. One of the most applied adaptation techniques responded by about (69.5%) of the participant was migrating to urban areas. This means that when the rural people unable to resist to climate change impacts, they migrate to nearby or far urban areas to find other livelihood options. Sometimes, they also build water harvesting schemes for irrigation, changing their practices from mixed farming to livestock herding and reducing the size of livestock (68.4%) and harvesting uncommon crops types (65.3%) and renting land for other farmers and from other farmers (63.2%). This shows that the local communities are trying to adapt climate change by using different mechanisms (See Table ).

Table 7. Adaptation mechanisms of climate change by respondents

Similarly, study conducted by Gezie and Tejada Moral (Citation2019) showed that there are local people who employed improved crop varieties, agroforestry practices, crop diversification, soil conservation, tree planting, off-farm activities, irrigation, adjusting planting dates, selling of assets, food aid, and permanent and temporary migration as climate change adaptation in Ethiopia. Besides, Mekonen and Berlie (Citation2021) noticed that crop diversification and agro-forestry using fertilizer (both organic and inorganic), soil and water conservation, Konso terrace and planting date adjustment were some of the adaptation options implemented by farmers in South Wollo, Amhara regional state. Furthermore, local people are applying area closure or reclamation of highly degraded areas. Watershed level soil and water conservation activities are being implemented by the local community and supported and promoted by the government. They are also expected to implement water harvesting and construction of terraces to reduce flood erosion. In addition government has been implementing huge land registration and certification programs to promote security and reduce boundary conflicts and resources based competitions aggravated by climate change.

Overall, the efforts made by the local community particularly from the Amhara side to cope up the impacts of climate change include using underground water for crop production and grazing, water ponding practices, growing less moisture requiring crops or short duration ripening crops. According to key informants, it is crucial to increase greenness and animal feed, either by introducing new varieties or managing the existing grazing land to ensure sustainable supply of animal feed and water. Moreover, the efforts made by the local government in collaboration particularly related to water resource management activities are either being devastated by Afar pastoralists when they invade the place for grazing and water or destroyed by the farmers because of low awareness.

4.6. Climate change and conflicts

In the study site, the participants of the survey were asked to list major causes of conflict on their localities (see Table ). Accordingly, the majority of them mentioned that resource degradation or scarcity (81.2%) and food shortage both for humans and animals (35.1%) and high temperature conditions (17.3%) (Table ) as the major causes for their conflict in the localities, respectively. In addition, in the study site, the participants of survey replied that about 81.5% of the conflicts were interpersonal between two or more individuals (78.5%) were intergroup or between two or more groups. This implies that in the study area, there are both inter personal and intergroup conflicts. Furthermore, survey participants believed that about 81.5% of the conflicts were interconnected and interethnic in their nature (77%) (Table ).

Table 8. Sources and types of conflict in the community

This also shows that in the study area, the conflict is caused by both resources scarcity and climate change and characterized as personal and interethnic conflicts. Similarly, climate change causes violent conflict by reducing economic output and crop yields, raising food prices, and increasing migration flows (Koubi, Citation2019). It also amplifies the existing economic, social and political risks that drive violence and increase the trend of poverty and income inequality and competition over controlling resources for survival. Stephen et al. (Citation2019), also found that Ethiopia has been plagued with the triple challenge of drought, food, and inter-communal conflict since the beginning of 2017 that initiate local conflict.

The FGD and KII participants also presented that conflicts were resources based, related to climate change and are most of the time between Amhara and Afar ethnic groups. This finding is similar to Koubi (Citation2019) who also indicated that climate change as potential factor, for intra-group violence through scarcity of renewable resources such as freshwater, agricultural land, forests and fisheries. It was also detected that high rates of rebel activity intensify with droughts, whereas communal conflicts escalate with anomalously wet conditions. In the same way, KII and FGD participants indicated that there is an increasing trend of conflict between individuals as well as between groups, mainly between Amhara and Afar ethnic groups. According to key informants and discussants participated in the FGD, resources based conflict is more prevalent in the bordering areas inhabited by Amhara and Afar communities. More particularly the conflict is between the pastoral Afar communities and semi-pastoral Amhara communities. Thus, range land and water resources-based conflict induced by climate change in the study area is largely characterized as ethnic in its nature and gradually becoming the security problem of the two regions. From temporal point of view, pasture or range land resources based conflict largely arises during dry season between January and July. During these months, water is extremely scarce for their daily needs and for their cattle. As a result, the Afars move with their large number of cattle including camel to the neighboring Amhara districts which consequently led to competition to control the water ponds or water springs between the two groups.

In the earlier times, the conflict was only the problem aroused by cattle keepers for grazing and water for their cattle and it was rear to consider the conflict as ethnic based. But these days, when there is a drought in the Afar and Amhara regions, the Afars move to the nearby Amhara region with a large number of cattle and literally invading the grazing lands, river springs, bore holes, and lands covered in crops, which consequently leads to conflict. Similarly, Stephen et al. (Citation2019) also confirmed that with ongoing climate change, population growth, and natural resources scarcity, there are suggestions that drought-induced migration which will lead to competition and stress in resource-scarce areas, with the potential to generate into violent conflicts. Forceful occupation and invasion of grazing and farm lands by Afar community is considered as a normal day to day activity in the study site. On the other hand, the land occupied and invaded by Afar community mainly during dry seasons is legally registered and certified land of the Amhara community. According to discussants participated in the FGD, the local communities are most often disappointed by the unfriendly and hostile actions of the Afar community. The key informants have also confirmed that the Afars mainly during dry season claim the lands of Amhara community as their land and they want to take and use forcefully.

The Afar pastoralists have larger cattle and camel herds than their counter parts and believed as highly devastating the pasture land. They are also mobile and can affect larger area including the crops of the Amhara and most of the time they kill and loot each other. Revenge killing and looting is a common practice in the areas and aggravated by resources sacristy. The conflict which usually instigated due to the competition to control over the use of grazing land and water supply for their animals gradually developing into ethnic nature. There is also a very barbaric tradition that considers killing and looting as symbol of bravery by both communities. This culture pushes both parties and communities to kill each. There is also a tradition to take those people defeated during the fight as captive. There is also a tradition to block road highways when conflict arises and ask payment to release a person taken as a captive and to open the road. In general, because of the continuous dispute between the two communities, the farming and grazing lands remained uncultivated and unused and most often the land has been abandoned for long time. Thus, it is very clear that a lack of security in the area has been contributing to landlessness, which has, in turn, led to a community that is food insecure.

According to key informants, significant number of local community in the study site consider temporary or permanent displacement as a strategy to survive shortage of food resulted from climate change and accompanied disagreements between the two neighboring communities. Particularly, the Amhara community mainly migrates to the local urban areas; Arab countries and Addis Ababa. They are also using begging as an option to survive. Generally, climate-change-induced migration can directly and indirectly affect conflict by affecting local living conditions which may increase the risk of conflict and lead to mass migration. Hence, climate change is leading into resource scarcity and in turn resources scarcity and initiate conflict in the study site in vicious way.

5. Conclusion and intervention remarks

The study has clearly demonstrated how conflicts have resulted from resource scarify and intensified by competition over the resources. It is also clearly revealed that climate change has been affecting the livelihood options of agricultural, pastoralists and agro-pastoralist communities in the study areas. This again has potentially a negative consequence for peace and security and started to become more and more ethnic in its nature particularly in the study site. To minimize the problem of security, resource scarcity and displacement, in Amhara and Afar border (conflict zone) the regional and federal governments should integrate the two communities through joint development projects that can serve the two communities including schools, health centers for people and cattle, irrigation dams, underground water development projects and common market places. The participants suggested that lack of clear boundary between Amhara and Afar regions is one cause of conflict. Hence, they have suggested that demarcating clear and agreed up on boundaries between the two regions or districts is another future action expected from the regional and federal governments. The regional government through discussion with concerned body should establish national or regional code or legal issue to solve the problem. The awareness creation campaign or training on how to use resources without conflict is also suggested as an important future action. Introducing sustainable natural resource development and management systems and working on weapon handling and introducing low land development strategy through irrigation, water harvesting and underground water utilization is very important. Strengthening customary/traditional institutions or capacity of religious, local, traditional leaders and local people is considered as an important element of future. In addition managing sources such as grazing lands and water sources should incorporate local bylaws and other legal codes. Reducing the livestock size and improving their feed is also another important issue that should be considered. Diversifying income options such animal fattening, petty trades and others by proving loans. In this case study, the Afar community saying about perception and experience about climate change conflicts should be investigated in the future.

Therefore, this study advises to introduce and implement conflict-sensitive climate change interventions in order to minimize unnecessary competition for controlling basic resources caused by scarcity as a result of drought. First, there is a need to improve the livelihood situation of the agro-pastoralist and pastoralist local community in drought sensitive areas by introducing and providing climate-smart livelihood options that promote food security. Priority should be placed on broadening food source options and diversifying natural resource based livelihoods such as introducing early-maturing crops and livestock breeds that are resistant to disease and drought. In relation to diversifying food sources, it is also essential to develop an early warning system before the occurrence of climate-related dangers such as drought. Secondly, it is important to promote water related climate resilient initiatives such as water harvesting during good rainy seasons and enhancing small-scale irrigation farming are essential. The capacity gap identification should be followed by capacity building programs tailored to address and manage climate-change-induced resources based conflicts and competing interests. This shows that the knowledge and skill on how to manage tensions and disputes induced by resource scarcity is very critical to promote sustainable peace. It is also important to know the importance of multi-stakeholder involvement in the process such state, civil society and local community.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We, the authors, are grateful to USIP (Climate-Driven conflict in Ethiopia: an AI/ML-Derived Neighborhood Level Risk Index with Ground truthing via primary data collection) project in Ethiopia for the financial support. We are also grateful to Fraym and its staff: Rob Morello and Geoff Tam who coordinated research and edited research report. We also thank Mr. Aragie Yimer who facilitated data collection from the research site.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, C. A. (2001). Heat and violence: Current directions in psychological science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(1), 33–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00109

- Aragie, T., & Genanu, S.(2017). Level and determinants of food security in north wollozone (Amhara region Ethiopia). Journal of Food Security, 5(6), 232–247. https://doi.org/10.12691/jfs-5-6-4

- Araro, K., Solomon, A., & Derege, T. (2020). Climate change and variability impacts on rural livelihoods and adaptation strategies in Southern Ethiopia. Earth Systems and Environment, 4(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-019-00134-9

- Bogale, G., & Zelalem, B. (2022). Drought vulnerability and impacts of climate change on livestock production and productivity in different agro-ecological zones of Ethiopia. Journal of Applied Animal Research, 50(1), 471–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/09712119.2022.2103563

- Brown, O. (2008). Migration and climate change. IOM Migration Research Series, (31).

- Cherinet, A. (2019). Climate change/variability impacts on farmers’ livelihoods and adaptation strategies: In the case of Ensaro District, Ethiopia. International Journal of Environmental Sciences & Natural Resources, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.19080/IJESNR.2019.18.555976

- CSA. (2021). Population projection of Ethiopia for all regions at Woreda level for 2020—2025. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency.

- FAO. (2015). Climate change and food security: Risks and responses. Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Fishman, R., & Li, S. (2022). Agriculture, irrigation and drought induced international migration: Evidence from México. Global Environmental Change, 75(75), 102548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102548

- Froese, R., & Schilling, J. (2019). The nexus of climate change, land use, and conflicts. Current Climate Change Reports, 5(1), 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-019-00122-1

- Gebre, E., Getachew, B., & Alemu, L.(2017). Application of remote sensing and GIS in characterizing agricultural drought in north wollo zone amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Journal Natural Research Research, 7(17).

- Gezie, M., & Tejada Moral, M. (2019). Farmer’s response to climate change and variability in Ethiopia: A review. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 5(1), 1613770. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1613770

- Hoffmann, R. (2022). Contextualizing climate change impacts on human mobility in African dry lands. Earth’s Future, 10, e2021EF002591. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EF002591

- Kassegn, A., Ebrahim, E., & Yildiz, F. (2021). Review on livelihood diversification and food security situations in Ethiopia edited by F. Yildiz. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 7(1), 1882135. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2021.1882135

- Koubi, V. (2019). Climate change and conflict. Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 343–360. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050317-070830

- Kwakwa, P. A., Alhassan, H., & Adzawla, W. (2022). Environmental degradation effect on agricultural development: An aggregate and a sectoral evidence of carbon dioxide emissions from Ghana. Journal of Business and Socio-Economic Development, 2(1), 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBSED-10-2021-0136

- Maxwell, J. W., & Reuveny, R. (2000). Resource scarcity and conflict in developing countries. Journal of Peace Research, 37(3), 301–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343300037003002

- Mekonen, A. A., & Berlie, A. B. (2021). Rural households’ livelihood vulnerability to climate variability and extremes: A livelihood zone-based approach in the Northeastern Highlands of Ethiopia. Ecological Processes, 10(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-021-00313-5

- Mera, G. A. (2018). Drought and its impacts in Ethiopia. Weather and Climate Extremes, 22, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2018.10.002

- Mertz, O., Halsnæs, K., Olesen, J. E., & Rasmussen, K. (2009). Adaptation to climate change in developing countries. Environmental Management, 43(5), 743–752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-008-9259-3

- Milán-García, J., Caparrós-Martínez, J. L., Rueda-López, N., & Valenciano, J. D. P. (2021). Climate change-induced migration: A bibliometric review. Globalization and Health, 1(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00722-3

- Mobjörk, M., Krampe, F., & Tarif, K. (2020). Pathways of climate insecurity: Guidance for policy makers. SIPRI Policy Brief.

- Mulugeta, K. (2011). The causes of Ethio-Somali war of 2006. https://repositorio.uam.es/handle/10486/677558

- Parrish, R., Colbourn, T., Lauriola, P., Giovanni, L., Hajat, S., & Zeka, A. (2020). A critical analysis of the drivers of human migration patterns in the presence of climate change: A New conceptual model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6036. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176036

- Ruwanza, S., Thondhlana, G., & Falayi, M. (2022). Research progress and conceptual insights on drought impacts and responses among smallholder farmers in South Africa: A review. The Land, 11(2), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020159

- Simachew, B., Daniel, M., & Arega, B. (2022). Trends and spatiotemporal patterns of meteorological drought incidence in North Wollo, northeastern highlands of Ethiopia. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 15(12), 1158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-022-10423-9

- Smith, D., & Vivekananda, J. (2007). A Climate of conflict: The links between climate change, peace and war. International Alert.

- Stapleton, S. O., Nadin, R., Watson, C., & Kellett, J. (2017). Climate change, migration and displacement: The need for a risk-informed and coherent approach. Overseas Development Institute and United Nations Development Programme.

- Stephen, A., Christina, R.-S., Benjamin, S., & Nadine, S. (2019). Drought, Migration, and Conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa: What Are the Links and Policy options?. https://www.idos-research.de/en/others-publications/article/drought-migration-and-conflict-in-sub-saharan-africa-what-are-the-links-and-policy-options/

- Sweijs, T., Haan, M. D., & Manen, H. V. (2022). Unpacking the climate security nexus: Seven pathologies linking climate change to violent conflict. The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies.

- VERBI. (2023). MAXQDA, The art of Data Analysis, MAXQDA 2020 Manual.

- Warnecke, A., Tänzler, D., & Vollmer, R. (2010). Climate change, migration and conflict: Receiving communities under pressure? Climate change and migration. International Journal of Research in Environmental Studies, 5(2018), 18–35.

- White-House. (2021). Report on the Impact of climate Change on migration. White House October. 2021 Report.

- Wolteji, B., Sintayehu, T., Sintayehu, L., Esayas, A., & Dessalegn, O. (2022). Multiple indices based agricultural drought assessment in the Rift Valley Region of Ethiopia. Environmental Challenges, 7, 100488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2022.100488

- Woodward, G., Perkins, D. M., & Brown, L. E. (2010). Climate change and freshwater ecosystems: Impacts across multiple levels of organization. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 365(1549), 2093–2106. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0055

- Zegeye, H. (2018). Climate change in Ethiopia: Impacts, mitigation and adaptation.