Abstract

Parental support is known to enhance the mental health and well-being of trans and gender-diverse (TGD) youth. Little is known about the impact of parental supportiveness on patient empowerment amongst youth seeking medical gender-affirmation. We evaluated the relationship between healthcare empowerment and perceived level of parental support in a sample of 176 TGD youth, ages 14–24, who responded to a healthcare empowerment survey. We used pairwise Chi-squared tests to understand significant associations between empowerment items and a four-point measure of parent supportiveness/unsupportiveness. Youth’s sense of control over gender-affirming medical care decreased with decreasing parental support (p < 0.001). Empowerment scores related to knowledge, decision-making, and supporting peers, did not differ between youth with very unsupportive and very supportive parents (p > 0.05). Youth with somewhat unsupportive parents consistently reported the lowest empowerment. This study adds to a body of work that suggests that high parental supportiveness for TGD youth yields positive outcomes. However, additional work is needed to understand the high levels of patient empowerment observed in youth with the most unsupportive caregivers and to explore how healthcare providers/systems can better support youth with somewhat unsupportive parents, who experience the lowest empowerment. Further work with a more nuanced parental support instrument is also warranted.

Introduction

As increasing numbers of transgender and gender diverse (TGD) youth are seeking gender-affirming medical care across the globe (Denaro et al., Citation2022; Handler et al., Citation2019; Wiepjes et al., Citation2018), a growing body of literature is exploring the influence of biological parents and custodial parents (e.g., adoptive parents, foster parents, stepparents; henceforth, parents) on the health and well-being of this population. These studies have shown that socially transitioned youth who are supported in their gender identity demonstrate similar levels of depression (Durwood et al., Citation2017; Olson et al., Citation2016) and self-worth (Durwood et al., Citation2017) compared to cisgender peers and siblings. Literature reviews related to the influence of family in the lives of TGD youth have found poorer mental health outcomes among youth with lower levels of family support (Westwater et al., Citation2019) and higher resilience among youth with greater parent connectedness (Tankersley et al., Citation2021). Parent connectedness has also been shown to lower odds of emotional distress, substance abuse, and suicidal thoughts (Gower et al., Citation2018; Wilson et al., Citation2016).

In efforts to access medical gender-affirmation, TGD youth are limited by lack of legal authority to consent to their own care, and even supportive parents may be reluctant to authorize medical intervention due to concerns such as future regret, discrimination, or impacts on long-term fertility (Clark & Virani, Citation2021). A recent systematic review and meta-ethnography (Kearns et al., Citation2021) exploring TGD youths’ experiences accessing gender-affirming medical care describes the parent role as ranging from critical facilitators to “insurmountable barriers” of care access (page 14). Indeed, following a TGD identity disclosure from a child, many parents must embark on their own non-linear gender journey (TransFamily Alliance, Citation2020) that can challenge held beliefs and values, require the seeking of resources and support, and trigger feelings of fear, doubt, and/or grief. This process may result in parents acting, with or without intention, as barriers to gender-affirming medical care.

Patient empowerment is broadly understood as the enhancement of knowledge, a sense of control, and decision-making engagement related to one’s healthcare (Cerezo et al., Citation2016). In the last several decades, as healthcare models have been shifting from paternalistic to collaborative care models, research into patient empowerment has been increasing (Barr et al., Citation2015; Mariela Acuña Mora et al., Citation2022). Patient empowerment has been shown to be positively associated with several key patient-centered outcomes, including improved quality of life, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and mental health outcomes (Mariela Acuña Mora et al., Citation2022).

Small and colleagues (Small et al., Citation2013) developed an empowerment framework with five domains: identity, knowledge and understanding, personal control, decision making, and enabling others. Grounded in this work, Acuña Mora and colleagues developed the first instrument designed to measure patient empowerment in young people, the Gothenburg Young Person’s Empowerment Scale (GYPES) (M. Acuña Mora et al., Citation2018), rigorously testing and validating overall and domain-level scores from their instrument. Working with this five-domain framework for understanding empowerment, we adapted the GYPES for use with TGD youth, reconceptualizing the instrument through a lens of normalized gender diversity and the importance of gender-affirming medical care in enabling TGD youth to reach their gender embodiment goals.

TGD youth seeking gender-affirming medical care navigate healthcare systems that are largely ignorant to gender diversity and gender health and are often outrightly hostile to TGD individuals, making the empowerment of this rapidly growing patient population critical. For all unemancipated minors and for many young adults, who may remain on their parent’s insurance until age 26, level of parent supportiveness of gender-affirming care can be a profound moderator of one’s ability to access medical gender-affirmation. The primary purpose of this analysis was to examine the relationship between patient empowerment and youth’s perception of parental support for accessing gender-affirming medical care.

Materials and Methods

We adapted the GYPES instrument for use in the TGD population with permission of its developers. To do so, we proposed initial instrument modifications to four transgender/non-binary youth, and then held a series of one-on-one virtual meetings with each of these youth testers to receive and discuss feedback on the proposed changes. This partnership with youth resulted in additional revision to the instrument. The final, complete survey included a single-item parental support question (How supportive are your parents/parents of you receiving gender-affirming healthcare) measured on a four-point Likert-type scale denoting level of supportiveness (very unsupportive, somewhat unsupportive, somewhat supportive, very supportive). The confidential survey was conducted online using HIPAA compliant REDCap survey (Harris et al., Citation2009) and was open for eight weeks in the spring of 2022. The study was approved by our healthcare system’s Institutional Review Board (Protocol #2022/01/3), including waiver of consent to facilitate data collection from youth under age 18 who may not be out to parents or able to participate under a requirement of parental consent. The study’s development and structure are described in greater detail elsewhere [Pflugeisen, et al., Citation2023, LGBT Health].

To explore the relationship between perceived parental support and item-level empowerment, we used Chi-squared tests of association and, in the case of small cell counts, Fisher’s Exact tests. We further explored significant associations between level of parent support and empowerment items using pairwise Chi-squared tests to understand significant associations by level of supportiveness. To account for the burden of multiple testing, significance was assessed at the α = 0.01 level; all analyses and data visualizations were conducted in the R statistical computing environment (Version 4.1.0, Vienna, Austria).

Results

A total of 177 respondents completed the survey; one did not indicate level of perceived parent support and was thus excluded, yielding a total of 176 respondents for this analysis. A majority of respondents reported that their parents were very supportive (n = 65, 36.9%) or somewhat supportive (n = 60, 34.1%) of their receiving gender-affirming medical care, while 18.2% (n = 32) reported somewhat unsupportive parents and 10.8% (n = 19) reported very unsupportive parents (p < 0.001). Level of parent support was generally consistent across demographic strata (see ). The percentage of transfemme youth who perceived their parents as very supportive was more than twice that (51.7%) of gender-diverse/non-binary identified youth (41.6%), but the overall relationship between gender identity and level of parent support was not statistically significant (p = 0.06).

Table 1. Distribution of caregiver support across respondent demographics.

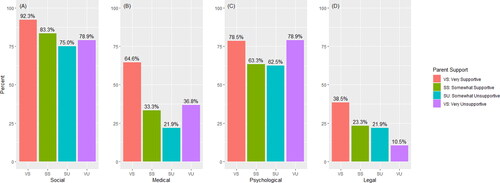

The extent to which youth had engaged the four dimensions of gender-affirmation, following Cicero’s framework (Cicero et al., Citation2019), which includes social, medical, psychological, and legal gender-affirmation, varied with level of parent support. In all but the dimension of legal gender-affirmation, a higher percentage of youth with very unsupportive parents had pursued gender-affirmation than those with somewhat unsupportive parents (see ). In the case of medical gender-affirmation, significantly more youth with very supportive parents (64.6%) had accessed gender-affirming medical care, compared to just 33.3% with somewhat supportive, 36.8% with very unsupportive, and 21.9% with somewhat unsupportive parents (p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Percent of youth who had engaged social, medical, psychological, and legal gender-affirmation at the time of survey completion, stratified by perceived level of parent support.

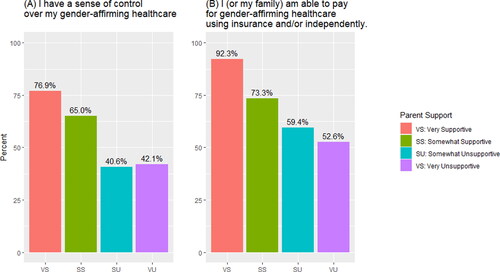

Seven of the 17 items in the empowerment instrument were significantly associated with perceived level of parent support. Notably, these associations existed across domains, with the exception of the identity domain. Two distinct patterns emerged in the relationships between item-level empowerment and perceived parent support: a negative, linear relationship and a curvilinear relationship between empowerment and parental support. The negative, linear relationship between empowerment items and perceived parental support was observed only in the control domain, with perceived control decreasing in direct relation to decreasing parental support. A higher percentage of youth with very supportive parents felt they had a sense of control over their gender-affirming healthcare (76.9%) compared to those with somewhat unsupportive (40.6%, p < 0.001) or very unsupportive parents (42.1%, p = 0.004; ). Pairwise comparisons also revealed a significantly higher percentage of youth with very supportive parents felt able to pay for their care (92.3%) compared to those with somewhat supportive (73.3%, p = 0.005) somewhat unsupportive (59.4%, p < 0.001) or very unsupportive parents (52.6% p = 0.004; ).

Figure 2. Significant, negative, linear relationships between parental support and sense of control over gender-affirming medical care.

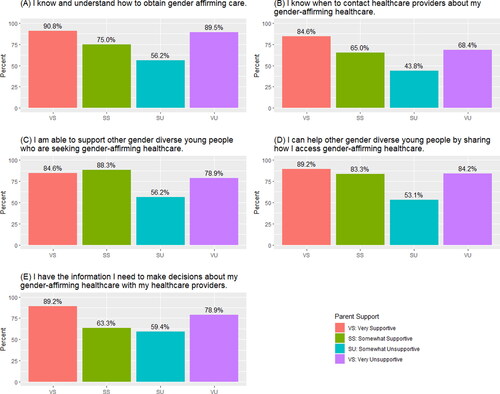

Empowerment and parental support showed a curvilinear relationship in the knowledge, decision-making, and supporting others domains. Youth who perceived their parents to be very supportive were significantly more likely to know how to obtain care compared to those with somewhat unsupportive parents (90.8% vs. 56.2%, pairwise p < 0.001; ) and to know when to contact their healthcare providers about their gender-affirming care (84.6% vs. 43.8%, pairwise p < 0.001; ). Strikingly, equivalent percentages of youth who considered their parents to be very unsupportive knew how to obtain care compared to those with very supportive parents (89.5% vs. 90.8%, pairwise p = 0.87; ). These youth were also as knowledgeable as their peers with somewhat supportive parents in knowing when to contact their healthcare providers (68.4% vs. 65.0%, pairwise p = 0.78; ). See () for additional details.

Figure 3. Significant curvilinear relationships between parental support and patient empowerment measures.

In the supporting others domain, youth with somewhat unsupportive parents were the least empowered to support their peers. Just over half (56.2%) of these youth expressed an ability to support peers seeking gender-affirming healthcare, compared to 84.6% of those with very supportive parents (pairwise p = 0.004) and 88.3% of those with somewhat supportive parents (pairwise p < 0.001; ). Similarly, youth with somewhat unsupportive parents were the least likely to feel they could help peers by sharing their own strategies for accessing care (53.1%), compared to those with very supportive parents (89.2%, pairwise p < 0.001; ).

Finally, significantly more youth who perceived their parents to be very supportive felt they have the information they need to make gender-affirming healthcare decisions with their providers (89.2%) compared to those with somewhat supportive (63.3%, p < 0.001) or somewhat unsupportive (59.4%, pairwise p < 0.001; ) parents. Here again we see a similar percentage of youth who perceive their parents to be very unsupportive feeling empowered in this aspect to those with very supportive parents (78.9%, pairwise p = 0.242; ).

Discussion

A substantial, and growing, body of work describes the importance of supportive parents in the mental and physical health and well-being of transgender and gender-diverse youth (Gower et al., Citation2018; Johns et al., Citation2018). The results of this study further support the positive impact of parental support in the lives of TGD youth, suggesting that supportive parents have the ability to significantly increase youths’ sense of empowerment within healthcare settings. As many trans and gender-diverse youth will engage in long-term medical gender affirmation (van der Loos et al., Citation2022), and the population seeking medical gender-affirming is rapidly increasing, empowerment in healthcare is crucial. This is especially urgent for this marginalized population that seeks gender-affirming and routine healthcare in environments that are generally ignorant or hostile to gender diverse individuals, and amidst a broader social climate that actively seeks to restrict access to care through legislative (Hughes et al., Citation2021; Kraschel et al., Citation2022; Turban et al., Citation2021) and sometimes violent (Christensen, Citation2022; Zipkin, Citation2022) methods.

Table 2. Empowerment items significantly associated with level of parent support.

In our study, youths’ sense of control over their gender affirming medical care and their ability to pay for that care decreased as parental support decreased. Fewer than 50% of youth with unsupportive parents expressed a sense of control over their gender-affirming healthcare. Such a lack of control has potential negative downstream effects such as impacting communication with healthcare teams, medication adherence, and continuation of follow-up care. Parent support is thus very practically (with regard to ability to pay for care) and impactfully (with regard to sense of control) influencing youth empowerment.

Entering into this study, our team hypothesized that we would see a linearly decreasing relationship between empowerment and parent support across all empowerment inventory items, but this was not the case. With respect to healthcare knowledge, decision-making capability, and the ability to support peers, youth with the most unsupportive parents reported patient empowerment at rates comparable to those with the most supportive parents. This is a striking finding. While the profound detrimental impact of parent unsupportiveness/rejection cannot be understated, examining the mechanisms that lead to patient empowerment for youth with the least supportive parents is important; a potential example may be mutual aid (Spade, Citation2020). Doing so acknowledges the resilience and resistance of youth who experience the most extreme forms of parental/familial transphobia and is meaningful work in its own right. However, such inquiry also has the potential to identify strategies and pathways that could be augmented for youth with somewhat unsupportive parents. These youth may be operating in a confusing and complex liminal space in which they youth cannot seek the care they need in direct opposition of parents who reject them outright but are also unable to seek the care they need in partnership with supportive parents.

The other notable pattern in our data is that youth with somewhat unsupportive parents consistently had the lowest patient empowerment. Indeed, our findings suggest that it is these youth, existing in the liminal space of neither parental acceptance nor parental rejection, who are the least empowered in healthcare spaces. This raises questions for healthcare providers about how to best support these families, in which parental tensions or hesitations related to medical gender-affirmation are functioning as impediments for youth, as well as questions around other ways in which youth with unclear family support may be disempowered. Are these youth cut off from the mutual support that may be accessed by those with very unsupportive parents? Are they waiting for their parents to progress in their own gender acceptance journeys before engaging fully in their own healthcare experience? Do families need system level support and therapy for the youth to be able to progress in their healthcare? These are questions that warrant further exploration.

Perception of parental support in this study was assessed using a single-item measure. While any perception of parental support is subjective, use of a multi-item, validated measure of perceived parental support, such as the Parental Attitudes of Gender Expansiveness for Youth (PAGES-Y; (Hidalgo et al., Citation2017)) questionnaire could provide a much more nuanced understanding of both perceived parental support and the elements of support that relate specifically to healthcare empowerment. This study is also limited in its representation of transfemme and BIPOC TGD youth, and intentional inclusion of these voices is necessary for any effort to achieve trans health justice. Additional work that addresses these limitations is needed.

Acknowledgments

We dedicate this work to the memory of the three trans youth our clinic lost to suicide in 2022, and to all people who are working in ways large and small to make the world a more just and safe place for trans and gender-diverse youth.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acuña Mora, M. A., Luyckx, K., Sparud-Lundin, C., Peeters, M., van Staa, A., Sattoe, J., Bratt, E.-L., & Moons, P. (2018). Patient empowerment in young persons with chronic conditions: Psychometric properties of the Gothenburg Young Persons Empowerment Scale (GYPES). PloS One, 13(7), e0201007. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201007

- Acuña Mora, M. A., Sparud-Lundin, C., Moons, P., & Bratt, E.-L. (2022). Definitions, instruments and correlates of patient empowerment: A descriptive review. Patient Education and Counseling, 105(2), 346–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.06.014

- Barr, P. J., Scholl, I., Bravo, P., Faber, M. J., Elwyn, G., & McAllister, M. (2015). Assessment of patient empowerment – A systematic review of measures. PloS One, 10(5), e0126553. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0126553

- Cerezo, P. G., Juvé-Udina, M.-E., & Delgado-Hito, P. (2016). Concepts and measures of patient empowerment: A comprehensive review. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da U S P, 50(4), 667–674. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0080-623420160000500018

- Christensen, J. (2022, August 17). Boston Children’s Hospital says it’s gotten violent threats over care for transgender children. CNN Health. https://www.cnn.com/2022/08/17/health/boston-hospital-gender-affirming-care-threat/index.html

- Cicero, E. C., Reisner, S. L., Silva, S. G., Merwin, E. I., & Humphreys, J. C. (2019). Health care experiences of transgender adults: An integrated mixed research literature review. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science, 42(2), 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1097/ans.0000000000000256

- Clark, B. A., & Virani, A. (2021). This wasn’t a split-second decision: An empirical ethical analysis of transgender youth capacity, rights, and authority to consent to hormone therapy. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 18(1), 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10086-9

- Denaro, A., Pflugeisen, C. M., Colglazier, T., DeWine, D., & Thompson, B. (2022). Lessons from grassroots efforts to increase gender-affirming medical care for transgender and gender diverse youth in the community health care setting. Transgender Health, https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2021.0092

- Durwood, L., McLaughlin, K. A., & Olson, K. R. (2017). Mental health and self-worth in socially transitioned transgender youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(2), 116–123.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.10.016

- Gower, A. L., Rider, G. N., Brown, C., McMorris, B. J., Coleman, E., Taliaferro, L. A., & Eisenberg, M. E. (2018). Supporting transgender and gender diverse youth: Protection against emotional distress and substance use. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55(6), 787–794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.06.030

- Handler, T., Hojilla, J. C., Varghese, R., Wellenstein, W., Satre, D. D., & Zaritsky, E. (2019). Trends in referrals to a pediatric transgender clinic. Pediatrics, 144(5), e20191368. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1368

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Hidalgo, M. A., Chen, D., Garofalo, R., & Forbes, C. (2017). Perceived parental attitudes of gender expansiveness: Development and preliminary factor structure of a self-report youth questionnaire. Transgender Health, 2(1), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2017.0036

- Hughes, L. D., Kidd, K. M., Gamarel, K. E., Operario, D., & Dowshen, N. (2021). “These laws will be devastating”: Provider perspectives on legislation banning gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 69(6), 976–982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.08.020

- Johns, M. M., Beltran, O., Armstrong, H. L., Jayne, P. E., & Barrios, L. C. (2018). Protective factors among transgender and gender variant youth: A systematic review by socioecological level. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 39(3), 263–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-018-0508-9

- Kearns, S., Kroll, T., O’Shea, D., & Neff, K. (2021). Experiences of transgender and non-binary youth accessing gender-affirming care: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. PloS One, 16(9), e0257194. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257194

- Kraschel, K. L., Chen, A., Turban, J. L., & Cohen, I. G. (2022). Legislation restricting gender-affirming care for transgender youth: Politics eclipse healthcare. Cell Reports. Medicine, 3(8), 100719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100719

- Olson, K. R., Durwood, L., DeMeules, M., & McLaughlin, K. A. (2016). Mental health of transgender children who are supported in their identities. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20153223. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3223

- Pflugeisen, C. M., Boomgaarden, A., Denaro, A. A., Konicek, D., Robinson, E. (2023). Patient Empowerment Among Transgender and Gender Diverse Youth. LGBT Health, May 2. 10.1089/lgbt.2022.0276. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37126404.

- Small, N., Bower, P., Chew-Graham, C. A., Whalley, D., & Protheroe, J. (2013). Patient empowerment in long-term conditions: Development and preliminary testing of a new measure. BMC Health Services Research, 13(1), 263. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-263

- Spade, D. (2020). Mutual aid: Building solidarity during this crisis (and the next). Verso Books.

- Tankersley, A. P., Grafsky, E. L., Dike, J., & Jones, R. T. (2021). Risk and resilience factors for mental health among transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) youth: A systematic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 24(2), 183–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-021-00344-6

- TransFamily Alliance. (2020). The TransFamily Gender Journey. https://www.transfamilyalliance.com/gender-journey/

- Turban, J. L., Kraschel, K. L., & Cohen, I. G. (2021). Legislation to criminalize gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth. JAMA, 325(22), 2251–2252. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.7764

- van der Loos, M. A. T. C., Hannema, S. E., Klink, D. T., den Heijer, M., & Wiepjes, C. M. (2022). Continuation of gender-affirming hormones in transgender people starting puberty suppression in adolescence: A cohort study in the Netherlands. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health, 6(12), 869–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-4642(22)00254-1

- Westwater, J. J., Riley, E. A., & Peterson, G. M. (2019). What about the family in youth gender diversity? A literature review. The International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(4), 351–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2019.1652130

- Wiepjes, C. M., Nota, N. M., de Blok, C. J. M., Klaver, M., de Vries, A. L. C., Wensing-Kruger, S. A., de Jongh, R. T., Bouman, M.-B., Steensma, T. D., Cohen-Kettenis, P., Gooren, L. J. G., Kreukels, B. P. C., & den Heijer, M. (2018). The Amsterdam cohort of gender dysphoria study (1972–2015): Trends in prevalence, treatment, and regrets. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(4), 582–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.01.016

- Wilson, E. C., Chen, Y.-H., Arayasirikul, S., Raymond, H. F., & McFarland, W. (2016). The impact of discrimination on the mental health of trans*female youth and the protective effect of parental support. AIDS and Behavior, 20(10), 2203–2211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1409-7

- Zipkin, M. (2022, October 21). CHOP tightens security following threats to its gender and sexuality clinic. Philadelphia Gay News. https://epgn.com/2022/10/21/chop-tightens-security-following-threats-to-its-gender-and-sexuality-clinic/