Abstract

Given a disproportionate scholarly focus on a high-profile litigation on manual scavenging – the manual cleaning of human faeces – in India, this paper aims to explore the experiences of NGOs led by Dalits – formerly “untouchables” – in navigating the judiciary to eradicate manual scavenging. It does so by first exploring the frequency and characteristics of court cases on manual scavenging, and second by exploring obstacles and opportunities that affect whether and how Dalit actors involve courts in their efforts. Through a mixed- and multi-method research, drawing on participatory field research, data from Right to Information requests, court judgments and interviews, the paper operationalises the concept of legal opportunity structure and shows that the choice to litigate is made carefully and is shaped by practical concerns. Notably, caste normativity both pushes Dalit actors towards litigation, and shapes how Dalit actors can engage with the judiciary. This power of caste to shape recourse to state law has serious implications for the idea that law and the judiciary are neutral and available to all equally. While previous literature focuses on public interest litigation and high-profile court cases on manual scavenging, this paper provides the first dataset on manual scavenging litigation, shows that such cases are the minority, and foregrounds experiences of Dalit actors.

Introduction

Over the decades, diverse actors trying to eradicate manual scavenging in India – the manual cleaning of human faeces – have tried it all. From civil disobedience, to education, to litigation, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), activists and manual scavengers themselves have drawn on extensive tactics to bring about liberation from the hazardous and exploitative labour (Singh Citation2020). Despite apparent successes – such as manual scavenging being repeatedly outlawed in India, most recently with the Prohibition of Employment of Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act 2013, and several high-profile cases at High Courts and Supreme Courts ordering local governments to take very explicit steps to eradicate manual scavenging – it persists rampantly. While this has led to several authors criticising that the movement against manual scavenging in India is hindered by over-reliance on litigation (Mandal Citation2008; Narula Citation2008), literature from other contexts suggests that the choice to litigate is always practically and pragmatically motivated (Gloppen Citation2018; Brierley Citation2019).

Given a lack of knowledge as to when actors choose litigation and courts as venues to challenge manual scavenging, this paper aims to explore the experiences of NGOs in navigating the judiciary to eradicate manual scavenging. Given that manual scavenging is deeply grounded in the caste system (Wankhede Citation2021), with Dalits – formerly known as “untouchables” – made to conduct most manual scavenging (Mahatme Citation2021), this paper specifically focuses on Dalit-led NGOs. This is operationalised through two sub-aims: First, it aims to explore the frequency and characteristics of court cases on manual scavenging, and second, to explore obstacles and opportunities Dalit actors claim affect whether and how to involve courts in their efforts. Through a mixed- and multi-method research, drawing on participatory field research, court judgments and interviews, the paper provides the first dataset on manual scavenging litigation, and builds on an existing framework by Gloppen (Citation2018) on the opportunity structure that moves actors to choose litigation as a forum.

Overall, the paper shows that given difficulties Dalit NGOs face in participating politically, litigation emerges as a main venue for progress. Importantly, litigation is not homogenous, and petitions take on different forms, and ask for different things, depending on the specific opportunity structure, i.e. context, risks of creating harms for manual scavengers, NGO representatives’ caste identity, and more. Notably, caste rules, and ensuing discrimination by upper-caste government officials, both pushes Dalit actors towards courts, and shapes how they can make use of litigation as a tool. While previous literature focuses on public interest litigation and high-profile court cases on manual scavenging, this paper foregrounds more quotidian experiences by Dalit NGOs, shows that public interest litigations are a minority, and provides a more comprehensive picture.

Structure of argument

After introducing manual scavenging specifically in the Indian context and the Indian government’s failure to eradicate it, the paper provides a brief overview of litigation on manual scavenging. Since existing literature focuses almost exclusively on high-profile public interest litigation, the paper shows that is not clear whether litigation is part of the standard repertoire of actions by most Dalit NGOs, nor what leads Dalit actors to rely on litigation when they do, and formulates two research aims. Drawing on existing research on the legal opportunity structure, the paper then shows that litigation is pursued when it directly appears the most promising given the facts at hand. After laying out the methodology that underlies the paper and how it operationalises the theoretical lens of legal opportunity structure, the paper presents descriptive statistics on a dataset of 80 cases related to manual scavenging. It then presents results from the two sub-aims in an interwoven manner: First, it explores this socio-economic and political opportunity structure of Dalit NGOs. Second, it explores how the legal opportunity structure results in diversity between types of petitions. Third, it explores how the legal opportunity structure impacts upon the wording of the plea put forward. Finally, findings are consolidated through a visualisation, and the paper concludes with suggestions for further research.

Introduction to manual scavenging

Manual scavenging defined

According to Indian law, “manual scavenging” refers to the “cleaning, carrying, disposing of, or otherwise handling” of “human excreta in an insanitary latrine or in an open drain or pit … before the excreta fully decomposes,” without proper devices and safety gear (2013, para. 2(1)(g)). It is prohibited for anyone, be it a public agency or a private actor, to employ a person to do such work. The government also recognises employing people to clean of sewers and septic tanks without safety equipment as hazardous (Ministry of Law and Justice Citation2013, para. 2(1)(d)), and prohibits it under the Act. In practice, manual scavenging of course does not neatly fit a rigid, legal definition (Sheeva Yamunaprasad Dubey Citation2018; Walters Citation2019), and manual scavenging is in practice any engagement with human faeces, in whatever state, at any stage along the sanitation chain.

Manual scavenging and caste

Manual scavenging is not caused by mere unprofessionalism or a failure to invest in proper equipment. Rather, it is deeply grounded in the caste system, which divides society into a hierarchy closely related to occupation (Mandal Citation2008; Human Rights Watch Citation2014; Yengde Citation2019; Dubey and Murphy Citation2021; Wankhede Citation2021). Dalits, formerly referred to as “untouchables,” fall outside the caste system, as they are considered ritually polluted. As B.R. Ambedkar groundbreakingly showed, ancient Hindu scriptures such as Naradasamhita and the Manusmriti first codified that untouchables would be forced perform a vast array of “polluting” work, under slave-like circumstances. In the Naradasamhita, for instance, disposal of human excreta is among the fifteen duties of the slave. Similarly, the Manusmriti set out that it is the duty of untouchables to serve upper castes, with no right to complain (Olivelle and Olivelle Citation2005). In exchange for the services by the manual scavengers, they were provided for instance with land to build their homes, and a refusal of the service meant that their land could be seized (Ambedkar Citation1989). To date, according to a 2021 survey by the Union Social Justice and Empowerment Ministry, 97.25 percent of people who do manual scavenging work are Dalits – even though Dalits make up only 16 percent of the Indian population (Mahatme Citation2021).

Non-enforcement of laws

Manual scavenging is currently outlawed in India under at least two Acts, the Prohibition of Employment of Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act and the Scheduled Castes and The Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. Regardless of several flaws in the Acts discussed at lengths elsewhere (Wankhede Citation2021), reports from grassroots NGOs show that neither are enforced: There have been barely any arrests, let alone convictions of people who employ manual scavengers, be they public agencies or private actors (Siddharth Citation2020; Khan Citation2018; National Campaign for Dignity and Eradication of Manual Scavenging Citation2013). The exact figures are unclear, as the central government’s crime statistics do not publish them. Data from the state of Karnataka show that 70 cases were registered between 2013 and 2019, with only one resulting in a conviction (Siddharth Citation2020). Similarly, while the families of manual scavengers who have died during their work since 1993 are entitled to financial compensation, ground reports have shown that they receive none at all, or only a fraction (Ramaswamy and Srinivasan Citation2017; Khan Citation2018; Kothari et al. Citation2020).

Additionally, while local governments are responsible for sanitation, they have in recent years increasingly outsourced sanitation work to third-party private contractors (Ramaswamy and Srinivasan Citation2017; Dubey and Murphy Citation2021). Several surveys of people doing manual scavenging tasks have consistently shown that only a minority are formally employed with the local government, and are rather hired as daily wagers. Given this informality, exact figures about how many people do manual scavenging tasks cannot be ascertained (Dubey and Murphy Citation2021; Harriss-White Citation2017, Citation2020; Pankaj and Pandey Citation2018). Because of this deliberately loose relation, government officials often claim that they are not the direct employer of a worker, and therefore not responsible for what happens to them, including death on the job (Dubey and Murphy Citation2021). In order to eradicate manual scavenging, the outsourcing system, denial of compensation and loans, failure to even identify people working as manual scavengers, and more must all be addressed.

Towards a literature gap: understanding Dalit-led litigation

Existing literature on litigation on manual scavenging almost exclusively discusses high-profile litigation. For instance, arguably every article on litigation on manual scavenging discusses the Public Interest Litigation (PIL) filed in 2003 by the Dalit-led NGO Safai Karmachari Andolan in the Supreme Court, which sought the enforcement of a 1993 Act prohibiting manual scavenging. PIL refers to a form of litigation in which a non-aggrieved person can approach a court to enforce fundamental rights, without any aggrieved person having to identified at all (Sorabjee Citation1997; Permutt Citation2011). During PILs, the Supreme Court has appointed commissions for fact-finding and prescribed step-by-step schemes and programs (Dhavan Citation1994; Sorabjee Citation1997; Permutt Citation2011). Indeed, the 2003 PIL is ground-breaking, as the Supreme Court maintained it for over a decade and issued several powerful interim orders (Wankhede Citation2021). Another oft-discussed landmark case was brought by thirty organisations from thirteen states that came together under the umbrella of the “National Campaign for Dignity and Rights of Sewerage and Allied Workers” (Supreme Court of India Citation2011). Some isolated authors have discussed older and less high-profile litigation, such as the very first petition on manual scavenging filed in 1995 by Dalit-led NGO Navsarjan in the Gujarat High Court (Shah et al. Citation2006).

Narula (Citation2008) and Mandal (Citation2008) have criticised reliance on courts and state law, arguing that “India’s social transformation project is stunted by its increasing dependency on courts as a source of redress” (Narula Citation2008, 266). However, there are grounds to doubt that Dalit NGOs struggling against manual scavenging resort to litigation too frequently. For instance, as Chitalkar and Gauri (Citation2019) find in their study, PILs have been filed on commercial and service-related issues much more than on social justice issues. Out of 177 PILs at the Supreme Court between 2009 and 2014, only one concerned untouchability, and there has been an increase in recent years in individuals who are not disadvantaged bringing PILs (Chitalkar and Gauri Citation2019, 82). Additionally, Narula’s (Citation2008) conclusion that reliance on litigation has rendered “other paths and options for the realisation of human rights virtually obsolete” (Narula Citation2008, 337–338) is arguably oblivious to the fact that litigation only emerged out of a social justice movement. Dalit NGOs have been recorded to use diverse tactics, including a months-long “yatra” (march, journey) across India (D’Souza Citation2016), demolishing dry latrines through civil disobedience, and protesting by smearing human excreta on their face (Ravichandran Citation2011).

This diversity raises questions regarding the role litigation takes, and why, when and how Dalit NGOs choose to resort to litigation when they do. In her research, Gloppen (Citation2018) is intrigued by “what leads activists towards courts and law as sites of contestation rather than other forms of mobilisation” (Gloppen Citation2018, 2). In addition to the material and social resources available, she shows that:

activists’ opportunity structure at the point at which a decision is made regarding whether and how to litigate, consists of the possible courses of action that they perceive as open to them, and the diverse set of factors that influence their assessment of the chances of succeeding with each alternative tactic, or combination of tactics. (Gloppen Citation2018, 19)

Against the backdrop of existing literature arguing that litigation is not chosen merely on a whim, it is intriguing to know more about whether, as Narula (Citation2008) says, there is an over-reliance on courts by Dalit actors. Given scholarly hyper-focus on high-profile litigation, it is simply not clear whether litigation is part of the standard repertoire of actions by most Dalit NGOs, nor what leads Dalit actors to rely on litigation when they do. In fact, given such lack of knowledge on the full breadth of cases, it is easy to come to prejudiced conclusions on the role and purpose of litigation within the strategy of Dalit resistance against manual scavenging.

Methodology

This paper broadly explores the experiences of Dalit NGOs and activists in engaging with the judiciary on manual scavenging. It approaches this through a mixed- and multi-method research and operationalised through two sub-aims: First, it aims to explore the frequency and characteristics of court cases on manual scavenging, and second, to explore the opportunity structure that affects whether and how Dalit actors involve courts in their efforts. Importantly, the research makes no claim to being comprehensive or exhaustive; rather, it is concerned with creating an initial basis for understanding the role of litigation in the wider struggle by Dalits against manual scavenging. Therefore, the methodology was not designed to involve a large sample size, nor to allow generalisation, but instead to propose a paradigm shift in the assumptions research on manual scavenging litigation is rooted in.

Theoretical lens: legal opportunity structure

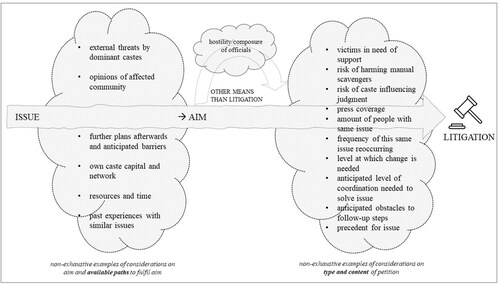

The methodology is informed by the theoretical lens of “opportunity structure” as put forward by Gloppen (Citation2018), which emerged as a central lens during the literature review. In her conceptualisation, an opportunity structure refers to “the sum of external and internal factors that influence [actors’] judgment of what is the possible and opportune course of action in the circumstances” (Gloppen Citation2018, 18). Gloppen (Citation2018, ) creates a very general conceptualisation of such factors, reprinted here in , and argues that NGOs consider their capacity, both financial and social, the responsiveness of the political system, and the specifics of litigation as a venue in the pre-litigation phase:

Figure 1. Reprinted from Gloppen (Citation2018, 17): . Activists’ choice situation – ‘mere’ legal mobilisation.” Copyright Siri Gloppen.

Especially the concept of a legal opportunity structure is central to the methodology of this paper, as Gloppen highlights that factors such as access to justice, access to resources and assistance, the courts’ responsiveness and willingness of judges, and more determine whether courts are perceived as a suitable venue for action. The methodology of this paper was guided by active probing for these factors, and by probing for additional factors specific to the case of manual scavenging and Dalit-led litigation that are not included in Gloppen’s (Citation2018) framework.

Aim 1: frequency and characteristics of litigation

In examining the experiences of Dalit NGOs in engaging with the judiciary, this paper first explores the frequency and characteristics of court cases on manual scavenging. This aim emerges in direct response to scholarly criticism that Dalit actors “over-rely” on litigation, even though no paper has examined whether litigation is in fact part of the standard repertoire of actions by Dalit NGOs other than those well-known. Fulfilling this first aim then creates a solid basis to proceed with the paper’s examination of Dalit NGO’s opportunity structure. It does so through right to information requests and manual identification of court cases via online databases.

Right to information requests

The government of India has excluded figures on arrests made in relation to manual scavenging in its annual crime report, and has not made public information on cases filed related to manual scavenging. Several requests under the Right to Information Act were filed to the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Social Justice Ministry, the National Crime Records Bureau and the National Safai Karamcharis Finance and Development Corporation. Under the Right to Information Act, any citizen of India may access information that is not sensitive and which the public authority maintains. Information sought concerned data on cases filed regarding manual scavenging, such as their nature, outcome and frequency. Requests filed included asks for copies of all judgments and orders at the High Courts of each state ordering the state government or concerned local authority to pay out one-time cash assistance, First Information Reports filed under Sections 5 and 8 of the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act 2013, and Section 4(i)(j) of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Amendment Act 2015, and the charge sheeting rate for cases registered under these sections.

Sampling

In absence of a satisfactory response to the Right to Information requests, cases that relate to manual scavenging in Indian High Courts and the Supreme Court were manually identified through press releases and announcements by NGOs, and through Indiankanoon.org and Casemine.com, using the search terms “safai karmachari/karamchari” (a cleaning worker more broadly), “sanitation worker” and “manual scavenging.” Judgments that were pronounced before 2013, cases which are clearly concerned with dry waste/garbage workers and sweepers, and bail applications of people arrested under the 2013 Act were excluded.

Analysis

Judgments were read thoroughly and entered into an Excel database. Metadata such as case type, nature of petitioner, outcome and year were manually added. A short descriptor sentence summarising the core issue in the cases was included. Using descriptive statistics and data visualisation in Excel, inferences were made regarding trends among this identified dataset.

Aim 2: socio-economic, political and legal opportunity structure of Dalit actors

Building on the results from the section above, the paper secondly explores the socio-economic, political and legal opportunity structure of Dalit actors by operationalising Gloppen’s (Citation2018) framework. This serves to understand what leads Dalit actors to rely on litigation when they do, and how their specific context and caste identity shapes the way they can engage with the judiciary.

Participatory field research

At the time of research, one of the authors worked for an NGO on manual scavenging in India, which increased the accuracy of the study and facilitated access to data. In 2019 and 2020, the author was present in “the field” and engaged with other actors in that way, and also that he himself participated in making advances towards the eradication of manual scavenging. In fact, as a person of Dalit origin, he himself experienced some of the same discrimination and barriers Dalit NGOs consulted for the research also mentioned. Given the ambiguity associated with terms such as action research, participatory research and ethnographic field research (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2018), this section refers to the researcher’s engagement as “participatory field research.” In this context, “participatory” refers to the author’s participation, rather than participation by research subjects. Presence in the field and participation in efforts to counter manual scavenging clearly depart from a view of the researcher as passive in generating data, which aligns with the explicit intention this paper has of foregrounding the experiences of voices who are otherwise excluded. The theoretical lens of legal opportunity structure clearly guided the field research by directing attention to specific questions and topics. Personal experiences of the researcher are considered as explicit data to be analysed in this paper, just as case studies and quotes written down from conversations were.

Interviews

While the research is concerned more broadly with the experiences of Dalit actors in navigating the judiciary regarding manual scavenging, the research operationalises the category “Dalit actors” through non-governmental organisations (NGOs). In addition to data generated during conversations in the participatory field research, seven interviews with a total of nine representatives from across India took place in December 2018, May 2019, and January, February and June 2022 and lasted approximately 30 minutes to 1.5 hours. NGOs were identified through the dataset of court cases, as well as personal connections and subsequent snowball sampling. Interviews took place with either one representative of an NGO, or several at a time in which case they took turns speaking on what they considered their area of expertise. As the research is not intended to be exhaustive, but to explore litigation on manual scavenging from a Dalit-led perspective, only seven interviews were conducted to identify tentative trends. The seven NGOs approached were deliberately sampled from different locations, so as to cover diverse geographies and contexts.

Given the COVID-19 pandemic ongoing at the time of data generation, interviews were primarily conducted in English via Zoom, WhatsApp or Google Meets. Interviews were semi-structured or unstructured given that interviewees were considered to have expert knowledge to guide the conversations. An interview guide based on the literature review, and an incorporation of initial findings on the nature and frequency of NGO-led litigation informed the interview process.

Analysis

Interviews were manually transcribed, correcting grammatical mistakes for the sake of clarity during analysis. Interview transcripts were manually coded using the software NVivo by assigning data excerpts, quotations, or entire passages one or several labels that summarise the key claim made, underlying assumptions, etc. (Chun Tie, Birks, and Francis Citation2019). Codes were considered relevant for analysis based on the framework by Gloppen, and themes were constructed by probing for the themes identified by Gloppen (Citation2018), i.e. normative, socio-economic, political and legal opportunity structure. Additionally, the analysis was guided by the trends identified during the descriptive statistical analysis of court cases above. Next, relations between the codes were spatially mapped out first via NVivo, and then in OneNote, in order to further identify overlaps and divergences from Gloppen’s (Citation2018) model.

Ethics

Part of this research was conducted as part of a Master’s thesis course at (redacted for review). Informed consent was taken from all interviewees, either orally or by email, and interviewees were offered anonymisation after the interview, and therefore after they knew what they had said. All interviewees whose names are mentioned consented to this. The paper is built on the feminist conviction that knowledge cannot be comprehensive and complete unless experiences from diverse actors are taken seriously, especially from those who have been historically marginalised (Grasswick Citation2011). Therefore, the paper deliberately foregrounds the experiences of a select few Dalit NGOs and activists who have not received scholarly attention so as to epistemologically include them in the “pool” of knowledge.

Turning towards the judiciary: a Dalit experience

Litigation on manual scavenging

In line with the first sub-aim of this paper, this section identifies trends in form, content, and frequency of litigation on manual scavenging. No statistics are currently available on the full spectrum of litigation on manual scavenging. Notably, the government failed to respond with satisfying information to the Right to Information requests discussed in the methodology section above, and responded that the data requested is not maintained.Footnote1 This is no surprise, as the literature review suggests that manual scavenging is – even deliberately – invisibilised. The participatory field research conducted by one of this paper’s authors further confirmed that the absence of data on manual scavenging litigation is not necessarily an oversight by researchers, but part of a larger system in which the Indian government does not maintain the information needed for such an overview. In response to this failure, this paper therefore, as laid out in the methodology section above, fully manually compiled a tentative dataset on litigation on manual scavenging.

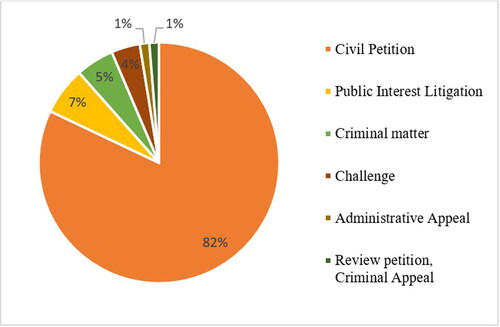

At least 80 relevant cases related to manual scavenging were identified at High Court and Supreme Court level across all of India since 2013. These 80 cases include cases filed by non-Dalit actors, families of deceased manual scavengers, non-Dalit and Dalit NGOs. 78 of these cases have been concluded, while 2 are not yet concluded.Footnote2 While existing literature primarily discussed public interest litigation seeking enforcement of the prohibition of manual scavenging more broadly, this dataset shows that issues of concern in the past nine years have been incredibly diverse: Pleas range from the provision of specific entitlements for manual scavengers if these were denied, to compensation in cases of death, to the enforcement of specific clauses in the 2013 Act. Claims directly on behalf of aggrieved persons are much more common than NGOs filing PILs, which suggests that existing literature’s focus on high-profile public interest litigations does not provide a comprehensive picture of manual scavenging litigation. This also highlights that litigation takes diverse forms and is indeed part of the standard repertoire of Dalit NGO actions. The type of petitions and the issues addressed are revisited in the sections below and discussed in more detail respectively.

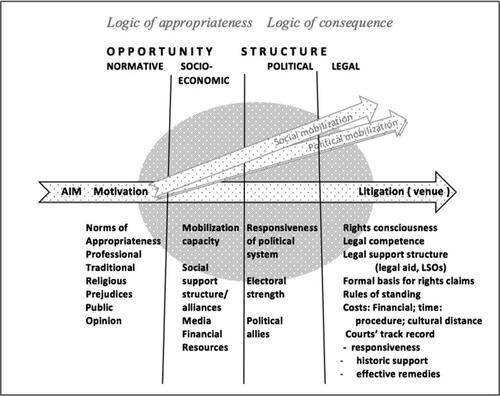

Based on qualitative analysis of interview and participatory field research, the following part explores this diversity further, by examining why Dalit NGOs choose to turn to courts for these asks, and why they choose to formulate the pleas as they do when they turn to the judiciary. Broadly, the following part therefore explore how this diversity of cases results from the experiences Dalit NGOs have in eradicating manual scavenging. It concludes that whether to litigate or not, and how to litigate, is drastically shaped by caste, through for instance external threats by dominant castes and anticipated hostility from government officials when pursuing other means. Additionally, the existence of concrete victims in need of help and the risk of the litigation further victimising them plays a large role in shaping the opportunity structure that makes litigation the preferred option. Apart from just impacting the opportunity structure that leads Dalit NGOs to turn to litigation, these considerations also affected the type of litigation chosen, and the wording of the plea, creating the diversity of cases laid out above.

Socio-economic and political opportunity structure

In Gloppen’s (Citation2018) framework, she introduces the existence of a socio-economic and political opportunity structure, i.e. the opportunities activists have to mobilise other means than courts to achieve their desired outcome. This section explores this socio-economic and political opportunity structure of Dalit NGOs. Notably, none of the NGOs expressed a preference for litigation as the go-to method, and consistently mentioned exploring alternative routes before considering involving courts, regardless of differences among their ultimate aims and foci. The response given by authorities, and the treatment the NGO receives while exploring these routes feature as a prominent consideration when considering litigation. For instance, as Thamate writes in its 2017 3rd Quarterly Report,

Mr K B Obalesh and Mr. Ramchandra, SKKS [Safaikarmchari Kavulu Samithi] member from Bellari met the official of Directorate of Municipal Administration and urged them to modify this rule. But the DMA [Directorate of Municipal Administration] has refused to modify this rule and therefore, SKKS members have sought an appointment with the Chief Secretary of Government of Karnataka to push for the matter. (Thamate Citation2017, 16)

As part of my knowledge, on what we are struggling for the last 15 years about this issue, the court cases are not fully helpful actually. It’s not ultimate, actually, it is not the ultimate solution.

So, what we are trying is to get it done through the representatives, and if still we do not get the status or satisfactory response for the community, then something can be done, then, as a last resort, we have to go to the court.

Like, we have a good network, we have good friends, we have good other officials, government or non-governmental people are with us. So definitely even if some problem comes, but I think we can overcome this problem.

See, in India, the thing is getting your date for a court hearing is quite long, it’s not a one-year or a two-year process. You have to keep in mind that it’s a long fight then you know, so, getting the legislation passed is a less time-consuming fight as compared to the court fight.

So my colleague […] led people to the local government office in the village and when he approached it, the chairman of the council, […] he shouted on the top of his voice, you know, very derogatory, saying, don’t bring those people here. Very derogatory.

When an activist from the upper caste community visits the government office to discuss about manual scavenging issue, he gets all kinds of attention because of his social capital and when a lower caste person visits to get documents or discuss about the issues of manual scavenging or Dalit rights the government officials get irritated and sometimes, they abuse.

As discussed above, the requests filed by the authors of this paper to the government of India under the Right to Information Act seeking information on cases filed regarding manual scavenging were not answered satisfactorily. In response to RTI request NCREB/R/E22/00044 filed on February 1, 2022, which asked for the “state wise numbers of FIRs filed under The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act 2013, from the year 2013 to 2021, and the copies thereof,” the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) provided the following response, translated from Hindi: “The specific information you have sought is not available with the CPIO.” Similarly, in response to RTI request NCREB/R/E22/00049, filed on February 2, 2022, which asked for the court disposal data for cases registered under the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities Act) clause related to manual scavenging, the NCRB responded, translated from Hindi: “The specific information you have sought is not available with the CPIO.” Notably, information on court disposal data is available with the NCRB for other crimes, such as rape and kidnapping. This invisibilising is not much of a surprise. After all, as emerges from the introductory sections, the government of India largely outsources sanitation work and fails to identify manual scavengers and provide them with compensation and rehabilitation loans. It also ironically underscores the difficulty in conducting informed research on, let alone in designing effective programs to eradicate manual scavenging.

In addition to seeking information through such requests, one of the authors also encountered similar hostility during participatory field research. In May 2019, the author conducted was present in Amanganj Nagar Parishad, and sought to collect data related to rehabilitation and compensation for manual scavengers. When he requested the data from the implementing authority, they responded: “Go to that room and check by yourself, if you find anything related to [the Manual Scavenging Act] take photocopies and go. Don’t bother me again asking about scavengers.” A year later, in May 2020, the author went to meet an officer of the Indian Administrative Services in Panna Nagar Palika Parishad to discuss the situation of manual scavengers in the Panna region. While the officer initially responded openly, this changed when the author inquired into the implementation of 2013 Act prohibiting manual scavenging, and requested documents related to the Act. The officer said he would ask his juniors to prepare the documents for us and asked the author to come back after lunch. However, when the author went to meet him again, it emerged that the officer had told his juniors not to allow the author near his office. The executive, therefore, also did not constitute a suitable source of information, nor the right actor to turn to, for data in this paper, which directly resonates with the experiences of Dalit NGOs interviewed above.

Yet, even turning to law and its tools did not always promise support. As activist Raja Karosiya highlighted, upper-caste lawyers he had encountered had often refused to take on manual scavenging cases. He argued that this was because contractors, against whom many cases are filed, posed too much of a threat, but also referred to caste bias. Activist Raja Karosiya from Panna, Madhya Pradesh, echoed this, saying:

Dr. Ambedkar gave us the best laws to protect us but the upper caste judiciary failed to implement it for the Dalits.

Type of petition

As shows, over 80 percent of the 78 cases concluded since 2013 were filed as civil petitions, and seven percent were public interest litigations. This suggests that only a small portion of cases filed on manual scavenging are public interest litigations.

Figure 2. Overview of broad nature of petition in 78 identified cases across India concluded since 2013 on manual scavenging and sanitation work.

As regards the form of litigation chosen – civil remedy petitions, PIL, etc. – considerations regarded both the resources available, threats each would pose to manual scavengers, as well as the existing legal basis. Ena of DASAM considered the existence of a solid legal basis a reason to invest in cases helping specific victims reap benefits from the legal basis:

Right now, what we are trying is that if you go through the Gujarat High Court guidelines, they are very elaborate. They map out all the necessary things. […] The guidelines are very elaborate and very descriptive, and we are trying to get that only implemented right now.

And in the public interest litigation, you have to do all the investigation yourself and build your arguments.

If you tell them directly, please come, we will fight for your issue, they immediately will be fired and lose the job also. So lot of time we face this problem. Some contractors and officers know this, and they know us, so four or five people have lost their job.

Wording of plea

As introduced above, among the 80 total cases identified, some cases directly sought regularisation or the payment of loans, while others simply asked for a response to be given to or preference to be given in an application. gives a more thorough breakdown of the issues addressed. Cases filed by NGOs primarily sought the release of information, and of funds to implement the 2013 Act. Given their temporal proximity and the same wording, the majority of cases seeking payment of loans, or seeking regularisation appear to have been part of a coordinated action, rather than individual actions.

Table 1. Overview of broad distribution of issues in 80 identified cases on manual scavenging and sanitation work.

NGOs mentioned several noteworthy considerations that factor into the concrete formulation of a plea, once litigation has been deemed the path forward. Sanjeev of DASAM argued that because of the undeniable reality of caste discrimination among judges, litigation should only concern small issues and make marginal gains:

And because the judge in India, you know, well, that most of the judges are biased. So they have the caste thing in their mind. […] Because some small issues will need to go to the court, but not a full-fledged case.

Well, because when we went to the court, the judges were well-trained. So they had read everything that was on the papers already. So it was as if they were just waiting for someone to file a case.

Discussion

As introduced above, the opportunity structure in which Dalit NGOs find themselves impacts upon first, different paths forward and whether to involve courts at all, and second, the type of litigation chosen and the wording of the plea. Given the emphasis placed in literature cited above on the context-specificity of the choice to litigate, since it is usually oriented at finding the best way to achieve a specific purpose, this section presents a tailored visualisation specific to the NGOs sampled in this research. While Gloppen’s conceptualisation sees social, political and legal mobilisation as paths that diverge, Dalit NGOs working on manual scavenging appear to prefer first approaching other paths, and then litigation, in a more chronological manner. The findings presented above also suggest that the type of litigation pursued, for instance PIL or civil remedy, depends on factors not included in Gloppen’s framework. For the sake of novelty, what Gloppen (Citation2018) has already laid out is not repeated here. Instead, visualises notable additional considerations that NGOs mention as important in their decisions to involve courts in their efforts to eradicate manual scavenging.

The opportunity structure that determines whether and how litigation is viable is broadly divided into two parts: First, what the concrete aim is, and whether the socio-economic and political opportunity structure makes other means viable; and second, once other means have failed or are expected to fail, the opportunity structure that makes some types and wording of petitions more suitable than others. The most notable nuances added to Gloppen’s (Citation2018) visualisation include that Dalit NGOs working on manual scavenging mentioned their own caste position and external threats from dominant castes as central factors. Additionally, Dalit NGOs strongly considered the balance of harms and risks inherent to litigation, and external factors that would mitigate or exacerbate these risks.

It is notable that considerations around caste have such weight that they significantly impact how Dalit actors can engage with the judiciary. This has serious implications for the rule of law and the idea that law and the judiciary are neutral and available to all equally. Caste normativity, and ensuing discrimination by upper-caste government officials, both almost forces Dalit actors to resort to courts, and hinders them in making full use of the same legal tools that others can make use of. The power of caste to shape the opportunity structure in such a manner becomes clear when recalling Merry’s (Citation1988) work on legal pluralism, which shows that society contains a multiplicity of rules, the minority of which are in fact formal law. In fact, while this paper critiques some of her scholarship, Narula (Citation2008) is correct in that the caste system can be understood as law if law is “understood as a set of rules backed by sanction” (Narula Citation2008, 295). While state law is therefore a tool that in theory should be used equally by all, caste rules have the force of non-state law, and significantly impact upon how state law works in practice.

Conclusion

In responding to ongoing scholarly concern about a lack of resourcefulness in countering manual scavenging, this paper has examined experiences of Dalit actors when seeking paths to eradicate manual scavenging, and focused on their experiences in engaging the judiciary. This paper has shown that the choice to litigate has as much to do with the issue at hand, as with the opportunities NGOs themselves have to affect any change, and emphasised especially the power of caste rules in shaping their access to effective means. This paper has therefore responded to criticism by Mandal (Citation2008) and Narula (Citation2008): While it is accurate that law is indeed not a magical tool to solve all problems, the choice to litigate is made carefully, and any alleged over-reliance on courts is brought about by the limitations of trying to eradicate manual scavenging while also being a Dalit. Given difficulties in participating politically, especially in light of caste discrimination, litigation emerges as the main venue available.

Importantly, litigation is not homogenous, and while caste pushes Dalit actors towards the judiciary, caste – alongside other factors that align with Gloppen’s (Citation2018) framework on legal opportunity structure – shapes what form petitions take and what pleas they contain. This diversity was noticeable among the 80 cases identified, although there was a clear trend towards civil petitions demanding the provision of entitlements enshrined in the 2013 Manual Scavenging Act. Given that the government absolves itself of its responsibility towards eradicating manual scavenging through outsourcing, demands for regularisation of work, compensation and loan payment were prominent. In distinguishing between different types of litigation, this paper has overcome previous research’s focus on just PIL.

Ironically, the research process for this paper itself was also impacted by issues addressed in literature, as the government absolving itself of its responsibility towards manual scavengers also means that it fails to collect and maintain relevant information. As such, cases on manual scavenging had to be manually identified when Right to Information requests proved insufficient.

Further research investigating other law-related strategies, such as efforts towards legislative change, could nuance what role involving the legal system – not just courts – is seen to have within the struggle to eradicate manual scavenging. Such future research could significantly contribute to a thorough understanding of the repertoire of activities, and opportunities available for actors working to counter manual scavenging.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 See the section on “socio-economic and political opportunity structure” below.

2 For the full list, see the thesis that this paper is based on: Kahle, Alena. 2022. “Of Legal Mobilisation and Active Citizenship: Examining NGO Litigation in India to Eradicate Manual Scavenging.” Master of Science, Lund University.

References

- Ambedkar, B. R. 1989. Essays on Untouchables and Untouchability. India: Independently Published. https://books.google.be/books/about/Essays_on_Untouchables_and_Untouchabilit.html?id=ubtvswEACAAJ&redir_esc=y

- Bhat, Mohsin Alam. 2019. “Court as a Symbolic Resource: Indra Sawhney Case and the Dalit Muslim Mobilization.” In A Qualified Hope: The Indian Supreme Court and Progressive Social Change, edited by Gerald N. Rosenberg, Sudhir Krishnaswamy, and Shishir Bail, 184–211. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Brierley, Alyssa. 2019. “PUCL v. Union of India.” In A Qualified Hope: The Indian Supreme Court and Progressive Social Change, edited by Gerald N. Rosenberg, Sudhir Krishnaswamy, and Shishir Bail, 212–240. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brown, Wendy, and Janet E. Halley. 2002. Left Legalism/Left Critique. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. doi:10.1215/9780822383871.

- Chitalkar, Poorvi, and Varun Gauri. 2019. “The Recent Evolution of Public Interest Litigation in the Indian Supreme Court.” In A Qualified Hope: The Indian Supreme Court and Progressive Social Change, edited by Gerald N. Rosenberg, Sudhir Krishnaswamy, and Shishir Bail, 77–91. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Chun Tie, Ylona, Melanie Birks, and Karen Francis. 2019. “Grounded Theory Research: A Design Framework for Novice Researchers.” SAGE Open Medicine 7: 2050312118822927. doi:10.1177/2050312118822927.

- Cohen, Louis, Lawrence Manion, and Keith Morrison. 2018. Research Methods in Education. 8th ed. London: Routledge.

- D’Souza, Paul. 2016. “Clean India, Unclean Indians. Beyond the Bhim Yatra.” Economic & Political Weekly, June 25.

- de Feyter, Koen, Maheshwar Singh, Dominique Kiekens, Noémi Desguin, Arushi Goel, and Devanshi Saxena. 2017. The Right to Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor in Delhi. Antwerp: University of Antwerp, Law and Development.

- Dhavan, Rajeev. 1994. “Law as Struggle; Public Interest Litigiation in India.” Journal of the Indian Law Institute 36 (3): 302–338.

- Dubey, Sheeva Y., and John W. Murphy. 2021. “Manual Scavenging in Mumbai: The Systems of Oppression.” Humanity & Society 45 (4): 533–555. doi:10.1177/0160597620964760.

- Dubey, Sheeva Yamunaprasad. 2018. “Subaltern Communication for Social Change: The Struggles of Manual Scavengers in India.” Doctor of Philosophy, University of Miami.

- Gloppen, Siri. 2008. “Litigation as a Strategy to Hold Governments Accountable for Implementing the Right to Health.” Health and Human Rights 10 (2): 21–36. doi:10.2307/20460101.

- Gloppen, Siri. 2018. “Conceptualizing Lawfare: A Typology & Theoretical Framework.” In Centre on Law & Social Transformation Paper, Bergen.

- Grasswick, Heidi Elizabeth, ed. 2011. Feminist Epistemology and Philosophy of Science: Power in Knowledge. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Harriss-White, Barbara. 2017. “Formality and Informality in an Indian Urban Waste Economy.” International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 37 (7/8): 417–434. doi:10.1108/IJSSP-07-2016-0084.

- Harriss-White, Barbara. 2020. “Waste, Social Order, and Physical Disorder in Small-Town India.” The Journal of Development Studies 56 (2): 239–258. doi:10.1080/00220388.2019.1577386.

- Human Rights Watch. 2014. Cleaning Human Waste - ‘Manual Scavenging,’ Caste, and Discrimination in India. New York: Human Rights Watch.

- Khan, Aman. 2018. Fact Finding on Manual Scavenging. Kanpur: Human Rights Law Network.

- Kothari, Jayna, Deekshitha Ganesan, I. R. Jayalakshmi, Krithika Balu, C. Prabhu, and S. Aadhirai. 2020. Tackling Caste Discrimination through Law - A Policy Brief on Implementation of Caste Discrimination Laws in India. Bangalore: Centre for Law & Policy Research.

- Mahatme, Vikas. 2021. “Unstarred Question No. 450: Religion and Caste Factor in Manual Scavenging.” Rajya Sabha Secretariat, December.

- Mandal, Saptarshi. 2008. “Through the Lens of Pollution: Manual Scavenging and the Legal Discourse.” Contemporary Voice of Dalit 1 (1): 91–102. doi:10.1177/0974354520080107.

- Merry, Sally Engle. 1988. “Legal Pluralism.” Law & Society Review 22 (5): 869–896. doi:10.2307/3053638.

- Ministry of Law and Justice. 2013. The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act.

- Narula, Smita. 2008. “Equal by Law, Unequal by Caste: The ‘Untouchable’ Condition in Critical Race Perspective.” Wisconsin International Law Journal 26 (2): 89.

- National Campaign for Dignity and Eradication of Manual Scavenging. 2013. Violence against Manual Scavengers: Dalit Women in India. Submitted to: UN Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women Her Visit to India between 22 April – 1 May 2013.

- Olivelle, Patrick, and Suman Olivelle. 2005. Manu’s Code of Law: A Critical Edition and Translation of the Manava-Dharmasastra. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Pankaj, Ashok K., and Ajit K. Pandey. 2018. Dalits, Subalternity and Social Change in India. London: Routledge.

- Permutt, Samuel D. 2011. “The Manual Scavenging Problem: A Case for the Supreme Court of India Note.” Cardozo Journal of International and Comparative Law 20 (1): 277–312.

- Ramaswamy, V., and V. Srinivasan. 2017. “The State and Urban Violence against Marginalized Castes: Scavenging in India Today.” In Proceedings of the Sixth Critical Studies Conference, Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata. http://www.mcrg.ac.in/6thCSC/6thCSC_Full_Papers/Ramaswamy_Srinivasan.pdf.

- Rao-Cavale, Karthik. 2019. “The Art of Buying Time - Street Vendor Politics and Legal Mobilization in Metropolitan India.” In A Qualified Hope: The Indian Supreme Court and Progressive Social Change, edited by Gerald N. Rosenberg, Sudhir Krishnaswamy, and Shishir Bail, 151–183. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Ravichandran, B. 2011. “Scavenging Profession: Between Class and Caste?” Economic and Political Weekly 46 (13): 21–25.

- Shah, Ghanshyam, Harsh Mander, Sukhadeo Thorat, Satish Deshpande, and Amita Baviskar. 2006. Untouchability in Rural India. ActionAid India. India: SAGE Publications.

- Siddharth, K. J. 2020. “Manual Scavenging in Karnataka a Situation Assessment.” Safaikarmachari Kavalu Samithi – Karnataka.

- Singh, Vikram. 2020. “Manual Scavenging: The Role of Government and Civil Society in against Discriminative Practice.” Social Work & Society 18 (2): 1–27. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:hbz:464-sws-2279.

- Sorabjee, Soli J. 1997. “Protection of Fundamental Rights by Public Interest Litigation.” In Public Interest Litigation in South Asia: Rights in Search of Remedies, edited by Sara Hossain, Shahdeen Malik, and Bushra Musa, 27–42. Dhaka: University Press.

- Supreme Court of India. 2011. Delhi Jal Board vs National Campaign Etc.& Ors. Supreme Court of India.

- Thamate. 2017. Quarterly Report | Oct - Dec | 2017.

- Walters, Vicky. 2019. “Parenting from the ‘Polluted’ Margins: Stigma, Education and Social (Im)Mobility for the Children of India’s out-Casted Sanitation Workers.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 42 (1): 51–68. doi:10.1080/00856401.2019.1556377.

- Wankhede, Asang. 2021. “The Legal Defect in the Conditional Prohibition of Manual Scavenging in India.” Contemporary Voice of Dalit : 1–12. doi:10.1177/2455328X211047730.

- Yengde, Suraj. 2019. Caste Matters. India: Penguin Random House. https://www.overdrive.com/search?q=82F58575-8386-416C-BD49-4D0D32AAAAC9.