Abstract

: In the past 15 years, there has been a dramatic increase in the global incidence of dengue and its severe manifestations, such as dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS). Epidemics in endemic countries are occurring more frequently with increasing magnitude. A well-managed front-line response not only reduces the number of unnecessary hospital admissions but also saves the lives of dengue patients. The objective of this study was to review the Dengue fever outbreak management in Dire Dawa City Administration Ethiopia, March 17_27,2021. The study employed a qualitative research approach, with thematic analysis. A purposive sampling method was used. Data were collected through FGDs, in-depth interviews, and document reviews. The results show there were qualified, experienced, and dedicated professionals for the management of the outbreak. In addition, the engagement of laboratory professionals to decrease the extent of outbreaks and to interrupt the rate of transmission was very interesting. However, the regional dengue fever laboratory investigation was limited to differential diagnosis because of the unavailability of diagnostic methods and essential laboratory equipment.

Public Interest Statement

Following the outbreak and its response, After Action Review (AAR) was done to review lessons learned from outbreak management in the wake of Dengue Fever outbreak in Dire Dawa city Administration to; identify best practices, gaps, lessons learned and how these practices can be maintained, improved, institutionalized, and shared with relevant stakeholders following an emergency response to a public health event. The AAR was undertaken to employ qualitative methodology over an extended period of fieldwork involving the collection of data through interviews, discussions, observations, and archival reviews. The review yielded important insights and the findings of this review are presented and discussed in this report. Before going to this, we first present in some detail a brief review of the literature on the benefits and scope of AAR followed by the objectives and methodology employed in this study

1. Background and Introduction

1.1. Background

Classic dengue fever (DF), or “break-bone fever,” is the most rapidly spreading arboviral disease with the highest prevalence in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world [Indian J Med Res 2013]. The virus belongs to the genus Flavivirus, a family of Flaviviridae with four serotypes known as dengue virus type 1, 2, 3, and 4 [Chemother. 1996]. DF includes severe forms of dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), and dengue shock syndrome (DSS), which can be caused by any of the serotypes. A person infected with one serotype is likely to develop DHF if later on infected with a different serotype but protected for the similar serotype ([Siqueira et al., Citation2004]). It is characterized by the acute onset of high fever 3–14 days after the bite of an infected female Aedes aegypti, a domestic day-biting mosquito. Even though most dengue infections are asymptomatic or cause a relatively mild disease, some DF infections may result in severe and potentially life-threatening disease ([Amarasinghe et al., Citation2011]). With early diagnosis and proper management, the case-fatality rate (CFR) of DHF is generally under 1%, but the CFR may be over 10% once shock develops ([Rigau-Perez et al., Citation2001]).

1.2. Introduction

Researchers emphasize the importance of post-incident discussion (i.e., After Action Review (AARs)) that highlights strengths, weaknesses, and near failures and describe the findings as a key feature of the safety culture for future actions (Soumyajit et al., Citation2013). Thus, AAR is a qualitative review of actions taken to react to an emergency as a means of identifying best practices, gaps, and lessons learned. Following an emergency response to a public health event, an AAR seeks to classify what worked well or not and how these practices can be maintained, enhanced, institutionalized, and shared with relevant stakeholders. It works by bringing together a team to discuss a task, event, activity, or project, in an open and honest environment. AARs can become a key aspect of the internal system of learning and motivation and should be a part of all emergency management programmers [WHO, 2018].

Following the outbreak and its response, After Action Review (AAR) was done to review lessons learned from outbreak management in the wake of Dengue Fever outbreak in Dire Dawa city Administration to; identify best practices, gaps, lessons learned and how these practices can be maintained, improved, institutionalized, and shared with relevant stakeholders following an emergency response to a public health event. The AAR was undertaken to employ qualitative methodology over an extended period of fieldwork involving the collection of data through interviews, discussions, observations, and archival reviews. The review yielded important insights and the findings of this review are presented and discussed in this report. Before going to this, we first present in some detail a brief review of the literature on the benefits and scope of AAR followed by the objectives and methodology employed in this study.

2. Review Methods

2.1. Study setting and population

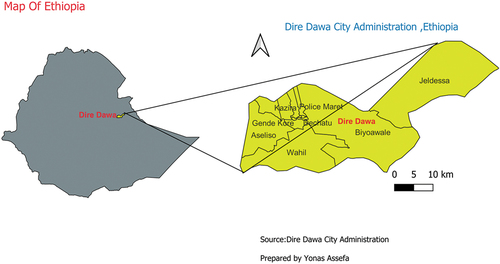

This AAR was conducted in Dire Dawa City Administration, Ethiopia. The Dire Dawa City Administration is located 516 kilometers (km) to the east of the capital Addis Abeba. It is bounded by Somali region from North and East. It is bounded by the Oromia region from the South and West. The average temperature of the area ranges from 68°F_91°F. It has a total projected population of 426,129. As shown in Figure ,study area map of Dire Dawa city administration.

2.2. Review Design

The present study employs a Qualitative Research approach with Thematic Analysis. Purposive sampling method was used.

2.2.1 Method and Data Collection

Data were collected through FGDs, in-depth interviews, observations, and document review. Data collection tools, interview guides and semi-structured checklists were prepared to generate data from RRT members, health professionals, and selected community members. A total of nine FGDs were conducted:

KII (Key informant interview). Twelve key important informants were selected for individual interviews from relevant offices in the health sector at all levels, from district to federal, based on the hierarchy of the current administration. The district health office directors, district PHEM units, RHB PHEM leads, national PHEM units, and specifically chosen RRT members at each level were some of the individual informants.

Focus Group discussion: A total of nine focus group discussions (FGD) were held (this is due to the hierarchy of the existing administration), out of which three-community FGD per affected woreda and six RRT/health workers were conducted. The health workers/professionals who participated in the FGD included clinicians, pharmacists/pharmacy technicians, and laboratory technologist/technicians, as well as one FGD from selected the community member. Moreover, there was one FGD for each level of government—national, regional, and zonal. In an FGD session, 8–10 people took part. Conversations were recorded using a digital audio voice recorder. Age was 34.3 years on average (SD = 8.5).

Document review: The following documents were reviewed during the collection of data:

Patient card reviews at health facilities

Review of daily and weekly reports at district health office and Zonal health department

Outbreak investigation report by zonal PHEM (Public Health Emergency Management)

A checklist and questionnaire were prepared/adapted for data collection.

Required resources were mobilized

Interviews and discussion were conducted on questions deriving from the core AAR functional areas/indicators: Surveillance; preparedness; Response; and Coordination. For observation as a supportive method, the team made systematic observations of relevant documents.

2.2.2. Data analysis

The data were recorded using a digital voice recorder. Translations from Amharic to English language and transcription, transcripts returned to participants for comment &/or correction, the analysis was done after the provision of feedback from participants. Management and analysis were done using Atlas.ti.9 software. The data were content coded for thematic analysis. Initial coding activity was based on prior conceptual categories, and further coding concepts were derived from the data. Explorations of coded data were done to conduct further analytical activities such as querying the data to find out frequently occurring concepts and themes, and relationships among codes and themes.

3. Result and discussion

The main conclusions of the review are given and addressed in the parts that follow. We will provide the results first, then we will examine the results in light of comparison standards and norms, adhering to the scientific approach to report format. The thematic method will be used to organize the results and discussion, starting with surveillance and moving on to Preparedness, coordination, and response.

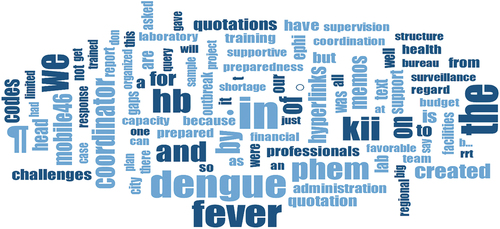

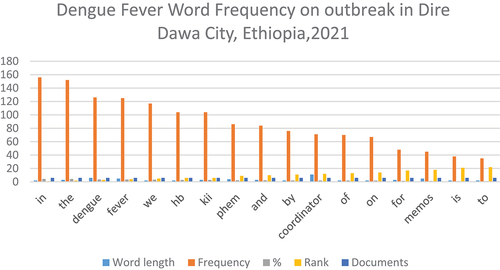

As seen in Figure , the most frequently used words were distinguished by larger size when compared to those that were not frequently used. Similarly, Figure word frequency bar graph shows the word that appeared most often throughout the document.

3.1. Surveillance

3.1.1. Result

This thematic issue deals with surveillance dimensions relating to the strengthening and capacity building of control mechanisms pertaining to the identification and reporting of dengue fever. Lessons drawn from the way surveillance of dengue fever incidence was undertaken during the 2019 mission will have a far-reaching significance in testing the systemic preparedness and capacity of the health system of the country down from the local to the federal levels.

This result section presents findings gleaned from the interviews, discussions, observations, and document reviews during the 4 months fieldwork relating to the issue of surveillance. The theme is sub-divided into five major categories: case detection and notification, data analysis, confirmation and communication, strength of surveillance and gaps, and challenges of surveillance. Following the presentation of the results, discussions of the key issues abstracted from the findings are presented, situating the key findings within national and international standards of relevant protocols as well as comparable reports from other countries. Surveillance is the collection, analysis, and interpretation of information about public health. An effective surveillance system helps health officials and experts to detect outbreaks of diseases and/or events.

3.1.1.1. Case detection and notification

Case detection and notification are the main activities to have a successful surveillance system. The national key informant respondent stated that the line list was prepared and distributed to the health facility to collect daily and weekly updates during and about the outbreak, adding that surveillance information was collected from the community and facility using different methods.

The disease is new and not common in the area before many of respondents agreed on it that , initially, they thought that it is other common febrile illness, especially malaria. As an FGD participant noted, “We got sick unable to eat and unable to move we went to health facilities, and they gave us medication similar to malarial drugs that we don’t clearly know it … .”

Both active and passive surveillance methods were used to detect the case as early as possible, as reported by a Legahare HC key informant, “we have done active surveillance by health Extension workers and passive surveillance at health center level. Communities also report to us when they observe unusual health problem…. Then we record it on rumour logbook.”

Similarly, Legahare RRT FGD respondents agreed with the key informant and said that the outbreak information received on two ways at OPD the clinician suspected the case and send to lab for confirmation when the number of cases increased above normal range the clinician suspect the occurrence of outbreak and report to RRT and head of HC, the other way is rumor from the community, but they always said malaria-like symptoms but when it reported frequently sample collected and send to higher-level laboratory for confirmation.

Participants from KII and FGD of different levels reported that their source of information to detect the cause was self-reporting at the outpatient department in their respective facilities: “Our source of information was the presence of clusters of cases in our OPD in daily and weekly report …” Gende Kore health center KII, which is also supported by Melka Jebdu HC HP FGD participants admitted that passive surveillance is more dominant than active surveillance in their case, which may affect early detection and notification of the disease.

After the case was identified, the notification activities were conducted well as many of our informants agreed from a Female FGD in Dire Dawa: “They informed us about dengue signs and symptoms like fever, chilling, excessive sweating, loss of appetite and vomiting likes that of malaria. We learned also about treatments and prevention as well as control mechanisms.” This is also supported by a Dechatu Community FGD participant who said that “committee members are aware of the community case definition of Dengue fever so that we can easily identify the case and immediately reported to the health center.”

3.1.1.2. Laboratory

3.1.1.3. Testing Capacity

In most health institutions, different tests were done to distinguish acute febrile illness diseases. The informants said that they have conducted laboratory tests such as blood film (BF) and Widal-welfix to rule out malaria, typhoid, and other febrile illnesses. One of the informants reported: “‘If the laboratory results did not indicate the above-mentioned diseases, we suspect dengue fever and treat based on sign and symptoms.’” However, the FGD participants at Dechasa Health Center pointed out that doing blood film and Widal-welfleix for each case increases the cost burden to the clients. Informants from Legahere Health center noted that a rapid test kit has been used for laboratory purposes.

A community FGD member from Gende Kore said that “‘laboratory service is very important since it is a confirmatory test for clinical examination. Unless we tested laboratory, we didn’t satisfy as correct diagnoses. I think this was reflected by all community members.’” One of the FGD members in another FDG discussion supported this idea and added that Laboratory service was available during the outbreak period at Melka Jebdu Health Center. This reveals that in most of the health facilities the laboratory testing capacity was good. However, the participants of another FGD reported that the treatment given after having a laboratory investigation was only anti-pain.

3.1.1.4. Laboratory Quality Assurance

Ensuring the quality of sample collection and use of standard operating procedures are important to improve the detection capacity of diseases including dengue fever. In this regard, the informants said that the sample collection was done by following the SOPs and hence the sample quality was good enough to detect the diseases (Diredaw HC head KII, Legahare HC head KII, Goro HC Head KII, Melka Jebdu HC FGD; 2021). Another informant further added: “‘We have placed all the necessary reference documents like logistics and supplies including SOP for sample collection and performing blood films visualizations,’” (Dechatu HC Head KII, 2021). The regional Health Bureau PHEM coordinator added: “‘our regional lab is not well organized, but we are working to strengthen it. For example, we don’t have the lab capacity to test arbo-viral,’” (RHB PHEM Coordinator, 2021).

3.1.1.5. Surveillance Data Analysis

Surveillance data was collected through active and passive ways. It always needs to be analyzed always to support early detection of the disease so that it is the most important activity in surveillance systems. Accordingly, we interviewed our respondents on how data analysis was conducted in their case. A key informant noted: “We discuss the condition daily and when we draw online graph the AFI cases increased dramatically, and the outbreak report compiled and sent everyday by line list.” Another key informant stated that the rapid response team always analyzes the surveillance data if there is any change of trend or any new cases, accordingly they take actions either by reporting to higher officials up to regional health office or by themselves.

3.1.1.6. Confirmation and Communication

Regarding confirmation and communication, the results show that after early challenges better works were done in this regard. Initially, most health facilities considered the disease as malaria and other febrile illnesses and treated the patients with the same protocol before it was confirmed that the case was dengue fever. To confirm during the focus group discussion, one of the participants said that they give due attention to any rumors and alerts raised from the community. After the outbreak was confirmed, the communication was reported as very good and effective at all levels.

3.1.1.7. Strength of Surveillance

It is well known that surveillance offers a scientific and factual database essential to informed decision-making and appropriate public health action, and its key objective is to provide information for interventions. Due to a variety of factors in developing countries including Ethiopia the Public Health surveillance system in general looks insufficient; however, in our study, a key informant from Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) stated that “information about the case definition and clinical manifestation of dengue fever were being disseminated to the community on a regular basis to help the community identify suspects and report to the local health facility and the health extension workers and community volunteers were among the key actors during the outbreak response.”

3.1.1.8. Gaps and Challenges of Surveillance

During interviews and group discussions, the informants acknowledged several gaps and challenges at all levels during the dengue fever outbreak response. Absence of TOR/MOU particularly at the health center level, irregular meeting schedules, limitation on surveillance data analysis, poor coordination system, poor laboratory access for investigating the newly emerging public health threats, media challenge for early warning and timely announcement, financial support for improving surveillance system, and also gaps in capacity building of the health workers like providing training and orientations, case detection using ongoing surveillance is critical during an outbreak response.

For instance, the national level key informant stated that there was in adequate and irregular meetings at national to regional level [National KII on DF, 2021]. He further explained that there was a challenge in active case search of Dengue fever after the second week of outbreak due to a lack of incentives. A key informant similarly opined that the lack of financial support, logistics, and infrastructure for improving the PHEM structure, including surveillance system at the health center level, was challenging. One of the key informants from the local health center stated that there was no coordination mechanism during outbreak response used to link different actors like the surveillance focal persons, the local administrative leaders, health workers, and so on; all concerned bodies were acting individually, and no EOC was established for the management of the disease outbreak (Legehare HC PHEM Focal KII, 2021).

3.1.2. Discussion

Surveillance is a critical component of any dengue prevention and control program as it provides the information necessary for risk assessment, epidemic response, and program evaluation. Surveillance can utilize both passive and active data collection processes. Depending on the circumstances under investigation, surveillance uses a wide variety of data sources to enhance and expand the epidemiological picture of transmission risk. However, in the present study, passive surveillance is the dominant one which is mainly dependent on self-report from affected individuals, thus resulting in delay of early detection and confirmation of the outbreak.

After confirmation of the outbreak, early warning and communication activities including active case search, line listing, alert letters, data compilation and analysis, case definition, and guideline distribution were conducted even though there were some shortages and delays reported in some cases, as per surveillance criteria of WHO AAR guidance (PHEM 2012). Active case search and line listing were better conducted in some of the study areas as the outbreak happened late.

The samples collected and transported to EPHI during the outbreak were in good condition even though there was some complaint about a delay in result communication. Generally, in this specific surveillance of Dengue fever, the human resource readiness and commitment were very good but, in some areas, financial and necessary material supplies were the common challenges that may have affected the overall surveillance activities.

The results presented above show that many of the study participants felt the surveillance of the Dengue virus infection outbreak response was weak and inadequate due to the above-listed gaps and challenges. It is true that a weakly functioning surveillance system could not be used to predict upcoming disease outbreaks, and this can be continuing to compromise the efforts of the countries’ health systems.

A comparable study conducted on Dengue virus infection in eastern Ethiopia by Mulugeta (2020) reports that there was no ongoing surveillance system for Arbovirus, cases were identified by reviewing medical records, rumor logbooks, and line lists as well as by conducting door-to-door active case searches with the help of community health extension workers and community leaders. A study by Soumyajit et al. (Citation2013) revealed that for improving the health system of any country, particularly for predicting disease outbreaks, a well-functioning public health surveillance system plays a fundamental role; no country with poor health system function should have a strong surveillance system.

3.2. Coordination

3.2.1. Result

There was a coordination of dengue fever response at all levels (National KII 2021). Dire Dawa Health Bureau Head opined: “In Dire Dawa after the rain stopped, three diseases appeared: chikungunya, dengue fever, and malaria; we responded to these three diseases by shared resources as well as by coordinating partners who provide support in this area. We responded to outbreaks both before and after the disease episode,” (KII Dire Dawa HB Head, 2021). Dire Dawa Health Bureau PHEM Coordinator also explained that there was coordination in pace during the response.

According to the Genda Gerada community FGD participants, there was coordination during a response to Dengue fever. “HEW and other village 09 officials and community committee members supported us in different coordination activities. We have two social networks with 50 members and 36 members, and overall, we use this for different social benefits of our community,” (Genda Gerada Female FGD 2021). Participants of Melka Jebdu Community FGD also reported that there was a coordination committee, called a health committee at the village level with 20 individual members. Local health center heads also reported that there was coordination between different sectors and teams to manage the dengue fever outbreak.

3.2.1.1. Risk Communication and Community Engagement

This theme is under response, and it deals with coordination, social/community mobilization, and engagement, behavior change communication, perception of the community preparedness, and response activities

3.2.1.2. Stake Holders’ Engagement

According to Dechatu HC, KII of PHEM there was engagement of stakeholders. Different informants generally reported that they were stakeholders who got involved. These included local leaders, religious leaders, community leaders, Dire Dawa University, Water Development Bureau, Dire Dawa City Administration, regional health office heads, EPHI, WHO, and CDC. The engagement of all these was reported as strengthening the response.

3.2.1.3. Stakeholders’ Engagement for RCCE

The findings from key informant interviews and focus group discussions show that on all levels, there was involvement in the outbreak control. Results from FGD further indicated that a wide range of participants were involved. It was generally found that during the dengue fever outbreak, public health awareness was created about dengue fever symptoms, transmission, vector control, and management. The community was encouraged to dispose of stagnant water and to use a bed net.

Further, participants also indicated that stakeholder engagement was a brought huge impact on the control of dengue fever, by educating the community, community mobilization, awareness creation, and identifying risk areas for dengue fever. However, community engagement was not uniform in the City Administration; according to informants, community engagement, and participation during the outbreak were limited. There was similarly little or no media campaign on the communication about dengue fever.

3.2.1.4. Communication channels utilization

Different communication channels were used to provide health education for the community. Participants from the region to the community level indicated that local FM radios, local TV broadcasts, house-to-house visits by health extension workers, posters and brochures, mobile health education by using Ambulance, by 1 to 5 women health development army and by using religious and community leaders.

3.2.1.4.1. Gaps and challenges of RCCE

The main challenge was the lack of budget allocation for risk communication and community engagement. Lack of community awareness and community resistance to implementing preventive measures of dengue fever are some of the additional challenges, according to participants. Further, a low level of multimedia utilization is also another challenge for RCCE: As FGD participants agreed, the community did not well utilize Ethiopian TV. “… Most people watch it for political gossip and entertainment programs.”

4. Discussion

Coordination is a very important pillar during any emergency response. The reviews of coordination emphasize sub-pillars such as the presence of the coordination system, its functionality, the presence of TOR/MOU, the engagement status of stakeholders, strengths, and challenges of coordination. All these sub-pillars were in practice during the Dengue fever outbreak response. The coordination system at the health facility and community level has contributed a lot and helped to control the outbreak. Public emergency coordination could be used to organize public health emergency response and helps for proper utilization of both material and human resource and timely control of the emergence Ferreira (Citation2012).

Different stakeholders have engaged during the response from national to local and community levels: regional health bureau, health centers, private pharmacies, Dire Dawa University, EPHI, WHO, and CDC. There were various committees at regional, facility, and community levels. The composition of committee members was from religious and community leaders, Dire Dawa University, the Center of Disease Prevention, the Water Development Bureau, and Dire Dawa City Administration Hygiene Department. At a community level, the composition of committee members was a health extension worker, religious leaders, community influential leaders, youth associations, and community representatives. Indigenous community networks have also played a major role in community coordination toward response. The commitment of the City Mayor and the Health Sector was highly seen despite many challenges.

Outbreak response planning has been identified to augment the engagement of partners, build capacity, and develop infrastructure, providing operational links to ensure a structured and coordinated response (WHO, Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases, Citation2010). There was no regular meeting regarding coordination. The presence COVID-19 pandemic has also prevented the conducting of regular coordination meetings. There was an interruption in coordination activity and an absence of regular engagement in other sectors. There was also the weak engagement of elders, traditional spiritual leaders, and mainstream religious leaders in some localities, which made coordination weak. Frequent interruptions in engagement with other governmental sectors were also a widely seen problem. Lack of proper utilization of the bed net for intended purposes was also the challenge encountered which was caused by the poor design of the bednet. Lack of beds due to case overload at some local health centers caused difficulty in giving other services because all beds were occupied by dengue cases.

Generally, the response to the DF outbreak has several strengths. A commitment of the city mayor and the health sector was highly seen despite many challenges. Active community engagement was also seen in during the response. Control activities for a dengue outbreak need to be multi-sectoral, multidisciplinary, and multilevel, requiring environmental, political, social, and medical inputs to be coordinated so that productive activities of one sector are not negated by the lack of commitment from another [TropIKA, 2010].

In some areas, resistance to accepting prevention methods and linking Dengue fever to the punishment of God some community members also encountered a problem. Hygiene and sanitation problems were also seen in some slum areas. The lack of TOR at many health facilities also caused poor coordination. The hot climate was also partly to blame for the poor coordination. Due to this hot weather condition, community volunteers and leaders were not working in the afternoon. Lack of logistics and finance also affected coordination at the health center level.

At all levels, there were stated roles and responsibilities of participants in the response. However, roles and responsibilities were not documented and signed TOR at almost all levels. There was also no MOU except at the regional level. At the community level, the roles and responsibilities were shared among different stakeholders and volunteers to coordinate community engagement during the outbreak response. There were few NGOs (partners) participated in the response. The lack of a full PHEM structure at the sub-national has contributed to weak coordination. Overlapping activities/work of staff was also a problem.

4.1. Response

4.1.1. Result

“Response” is one of the main thematic pillars under After-Action Review (AAR), which is used to describe whether the right response was put in place or not in all aspects of interventions from case management, prevention and control, and vaccination campaigns. It is requisite to manage the case effectively. This theme is divided into five sub-thematic areas: availability of response plan, active and effective rapid response team, case management, community participation in response, health education, the strength of the response, weakness of response, and challenges of response during Dengue fever outbreak.

4.1.1.1. Response Plan and Rapid Response Team

Public health emergency response should start by preparing a response plan. Accordingly, there was an active Rapid Response Team during the Dengue Fever outbreak. The rapid response team has a different team composition. According to the informants, the team is composed of health extension workers, laboratory technicians, pharmacists, environmental experts, and PHEM focal (Dechatu HC PHEM KII, 2021). Another KII from Lagahare Health Center described the team composition as follows: “the rapid response team has a medical doctor, public health Emergency management focal (PHEM), pharmacist, laboratory technician, and Health Center Director (Lagahare HC head KII, 2021).

The rapid Response team has defined roles and responsibilities. KII from Lagahare Health Center and Melka Jebdu Health Center described the roles and responses of the rapid response team (RRT) as follows:

Roles and responsibilities of a Medical Doctor (MD) are responsible to do a clinical assessment and confirm suspected cases according to case definition. The emergency management focal (PHEM) is to coordinate outreach programs, prepare PHEM-related plans and report for health center and health extension, and receive rumors from the community. The pharmacist is to identify the availability of supplies and to avail the required supplies. The laboratory technician is to collect samples and conduct sample testing. The Health Center Director controls and manages the overall activities of RRT, leads the meeting, and creates coordination and collaboration with stakeholders. (Lagahare HC Head KII, 2021 and Melka Jebdu HC Head KII, 2021)

4.1.1.2. Prevention, Control, and Case Management

Prevention and control focus on interventions after the dengue fever outbreak occurred. In this regard, it was generally reported as a very good prevention and control intervention during the response period. A key informant at a Ganda Kore health center noted: “We observe the affected households around index cases; their utilization of mosquito net; waste disposal practices and taught them to dispose of wastes properly …” (Ganda Kore HC HP KII, 2021).

A Ganda Kore Community FGD participant noted that “After patients were discharged from treatment health professionals and community health committee came to our home for follow up and they advised us on how to remove wastes.… ” (Ganda Kore Community FGD, 2021). Dechatu HC HP FGD Participant described the experience: “We visit even unexpected places like toilet and drained the collected water. In this regard we did great job. We also taught the community what insects look like in the larva stage and they started draining every kind of collected water. This is the good practice we had” (Dechatu HC HP FGD,2021).

Ganda Kore HC FGD participant noted: “There were identified places which can be considered as risky because of mosquito breeding places and a prompt response taken at all levels. The Family Health team has also been doing a lot of work; twice a week they supervise villages and homes in collaboration with HEW and health professionals from the health center” (Ganda Kore HC FGD, 2021). And similarly, Goro HC head KII noted: “There were more than 60 mosquito breeding sites in our town that were identified for malaria. Dengue fever and malaria have similarities regarding breeding. Due to this, we had worked on these breeding sites” (Goro HC head KII, 2021).

Regarding Emergency Operating Center (EOC), few health centers have established Emergency Operating Center (EOC) and others have not. A key informant from Lagahare Health Center described: “Separate Emergency Operating Centre for Deng fever was not established at regional and health center level. The responses were given by the public health emergency process. At the health center level, the response was given by the Rapid Response Team” (Lagahare HC head KII, 2011). In contrast, a key informant from Dechatu Health Center noted: “EOC was activated at the Health Centre level and the entire activities were coordinated by the regional health bureau followed by EOC of the health center… ” (Dechatu HC head KII, 2021).

4.1.1.3. Stakeholder Engagement

Risk communication is a prominent part of outbreak response, and many documents stated the need to regularly update the public on the outbreak. Interviews show, in overall, that there was an active engagement at all levels from partners and government actors following the Dengue fever outbreak. According to a key informant interview with Dire Dawa Health Bureau, when a dengue fever outbreak happens, all stakeholders, including Agriculture Bureau, Water and Sewerage, Construction Bureau, Water, and Sewerage Bureau, Security and Sanitation, and the WHO took part (Dire Dawa Health Bureau KII, 2021). Another key informant from Ganda Kore described that NGOs and other governmental organizations did significant support (Ganda Kore HC head KII, 2021).

4.1.1.4. Community Participation

Interviews and discussions show that, overall, there was an active engagement at grassroot levels from the community following the Dengue fever outbreak. A participant from the Ganda Kore Community FGD reported: “In our locality, there was a good movement, and we didn’t encounter any difficulty in the community as well as in the health center. Different stakeholders came from the local administration and information transfer was better” (Ganda Kore Community FGD, 2021). Similarly, participants of health professional FGD at Ganda Kore Health Center noted that they did a lot of activities regarding the response and prevention of the disease (Ganda Kore HC HP FGD, 2021).

4.1.1.5. Strengths of Dengue Fever Outbreak Response

When we reviewed reports from our informants regarding dengue fever outbreak response in general, we noticed admirable tasks were done, despite the presence of many challenges. Health professionals, community representatives, and government officials did many recognizable tasks. According to one of our informants at a national level, a higher official at EPHI, stated, “There was good communication and information exchange between national and regional teams.”

4.1.1.6. Gap and Challenges of Dengue Fever Outbreak Response

The main challenge and gap faced during outbreak management was a shortage of operational costs and trained human power. Our informants at the national level, as higher officials at EPHI, stated that “There was a shortage of operational costs and shortage of adequate manpower such as epidemiologists and laboratory professionals,” (National PHEM KII, 2021). Another major challenge was the COVID-19 pandemic. One of our informants stated that “This year we have a double burden because of the COVID-19 pandemic, so there was a big challenge to manage both cases” (Dire Dawa Health Bureau KII, 2021).

Another challenging issue was the shortage of health professionals because of increased patient flow and some of the health professionals were sick. One of our participants, a health professional at Ganda Gerada Health Center, stated that “The challenge we had was a shortage of health professionals because some health professionals were sick. We solved it by assigning those health professionals, not on duty,” (Ganda Gerada HC RRT FGD, 2021). He also added there were an awareness gap and shortage of pure water supply in the community “…People in the community were resistant to dispose of infested water because they have a shortage of pure water” (Ganda Gerada HC RRT FGD, 2021).

4.1.2. Discussion

Public health emergency response focuses on rapid assessment of outbreaks, outbreak investigations, implementing control and prevention measures, and monitoring of interventions. The benefits of a rapid and effective response are numerous. Rapid response limits the number of cases and geographical spread shortens the duration of the outbreak and reduces fatalities. These benefits not only help save resources that would be necessary to tackle public health emergencies but also reduce the associated morbidity and mortality. It is therefore important to strengthen the epidemic response, particularly at woreda and community levels. Attention needs to be focused on response strategies and continuous monitoring and evaluation of these activities [PHEM Guideline, 2012].

All-hazard plans should be developed for preparedness and response at national, regional, and district levels. Plans at all levels should be in line with the overarching national preparedness and response plan for the health sector and consistent with the overall national policies, plans, and emergency management principles. The purpose of this plan is to build the ability of the national and sub-national levels to respond promptly when an outbreak or other public health event is detected (WHO Regional Office for Africa, 2019).

The objective of the Rapid Response Teams (RRT) at all levels is to establish an early warning and reporting mechanism for potential epidemics. This includes information gathering, investigation, verification, and appropriate response. Managing disease outbreaks is one important aspect of disaster response, and by heightening the preparedness level of the RRT, they will be able to deal with all potential public health threats following disasters [Bista et al., 2003]. A Public Health Emergency Rapid Response Team (PHERRT) is a technical, multidisciplinary team that is readily available for quick mobilization and deployment in case of emergencies to effectively investigate and respond to emergencies and public health events that present significant harm to humans, animals, and environment irrespective of origin or source [WHO Regional Office for Africa, 2019].

Dengue and its severe forms, namely, dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS), are caused by four serotypes of the dengue virus [National Arboviral Diseases Surveillance and response Guideline (NADSR),2022].

The main method to control or prevent the transmission of dengue fever is to combat the mosquito vectors. This is achieved through environmental management and modification, personal protection from mosquito bites, active mosquito and virus surveillance, and community engagement (NADSR Guideline, Citation2022).

All of the aforementioned response mechanisms—case management, health education, vector control, and prevention—were in place as per standard, as it was shown above in the result section. The RRT team was made up of a distinct class of medical experts, with each team member having well defined duties and responsibilities. Cases were handled using the life-saving drugs that were on hand. Health extension workers, trained community representatives, and religious leaders provided the community with health education about dengue fever management, vector control, and prevention. They advised them to get rid of stagnant water, wear long sleeves, use a bed net, and apply mosquito repellents like Vaseline. A hospital visit was advised if any of the disease's symptoms appeared. However, there may be underreporting.

5. Conclusion

Based on the information collected from the informants and participants we can conclude that there were qualified, experienced, and dedicated professionals for the management of the outbreak. In addition, the engagement of laboratory professionals to decrease the extent of outbreaks and to interrupt the rate of transmission was very interesting. However, the regional dengue fever laboratory investigation was limited to differential diagnosis because of the unavailability of diagnostic methods and essential laboratory equipment. Because of the rapidly increasing public health importance of the disease, strengthening the laboratory testing capacity of the region should be given attention.

As per the PHEM guideline, dengue fever (DF) has become a major international health problem affecting tropical and sub-tropical regions around the world—especially urban and peri-urban areas. Dengue surveillance is difficult to establish and maintain. DF is a complex disease whose symptoms are difficult to distinguish from other common febrile illnesses. Surveillance of DHF holds special problems. The results presented above show that surveillance of the Dengue virus infection outbreak response was weak and inadequate due to the above-listed gaps and challenges. Indeed, a weakly functioning surveillance system could not be used to predict upcoming disease outbreaks, and this can be continuing to compromise the efforts of the country’s health systems.

Arboviral illnesses are prevalent in Dire Dawa. It saw numerous occurrences of dengue fever, chikungunya, and malaria outbreaks. Due to these circumstances, a health bureau, health professionals, community representatives, and the community should be knowledgeable about how diseases are managed, how to prevent outbreaks, and how to control vectors. The above-mentioned outbreak response has some commendable strengths. For instance, information sharing between the national and regional health bureaus is beneficial and assisted in the timely containment of the outbreak. The presence of skilled community representatives, devoted health professionals, and an effective leadership style are among the other positives highlighted in our result above. These are the things that determine how an outbreak will turn out, reducing its duration and damaging effects.

In general, different gaps were identified on every subtopic on coordination, preparedness, response, surveillance, laboratory, logistics, medical supplies, information and communications, and others that needs to be focused on to save lives and prevent new cases.

6. Declaration

1.1. Ethics approval and consent to participate

According to Federal Negarit Gazeta of FDRE Regulation No.301–2013, EPHI establishment council of Ministry of Regulation page 7175, 20th year 10 Addis Ababa 1 January 2014, Ethiopia Public Health Institute has a power and duties to conduct, during epidemics or any other public health emergency or public health risk, on sight investigation when deemed necessary, verify outbreaks, issue alert, provide warning, and disseminate information to the concerned organs, mobilize or cause the mobilization of resources, support the response activities carried out at woredas, zones, and regional levels as deemed necessary and “implement international health regulations on grave public health emergencies implying international crisis; Article 14 and 16, respectively.

This study has been done in conformity with the ethical codes of clearance approved by the Ethiopia Public Health Institute (EPHI, ref: 3.10/446/14) to Dire Dawa City Administration and proceeded by the permission request letter from Dire Dawa City Administration Health Bureau 33-/86/261/14 written to the zonal health bureau than to the respective health facilities and explaining the study objectives and its significance.

The qualitative study was informed by, among other things, respect for culture, local norms, privacy, and principles of honesty, truth, and beneficence. The audio-visual recording was done by obtaining permission from the participants. Consent was read for each FGDs participant and the discussion was continued with the approval of each participant, based on the FGD tools in AAR templates.

Abbreviations

| AEFI | = | Adverse Effects Following Immunization |

| AMREF | = | African Medical and Research Foundation |

| AAR | = | After Action Review |

| CDC | = | Center Disease Control |

| DD | = | Dire Dawa |

| DDG | = | Deputy Director General |

| DF | = | Dengue Fever |

| DSS | = | Dengue Shock Syndrome |

| EOC | = | Emergency Operation Center |

| EPHI | = | Ethiopian Public Health Institute |

| EPRP | = | Emergency Preparedness and Response Plan |

| FGD | = | Focus Group Discussion |

| FMOH | = | Federal Ministry Of Health |

| FDRE | = | Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia |

| HC | = | Health Center |

| HO | = | Health Office |

| KII | = | Key Informant Interview |

| LLITN | = | Long-Lasting Insecticide Treated-Net |

| MOH | = | Ministry Of Health |

| MOU | = | Memorandum Of Understanding |

| NANDSR | = | National Arboviral Diseases Surveillance and Response Guideline |

| OPD | = | Outpatient Department |

| PHEM | = | Public Health Emergency Management |

| RCCE | = | Risk Communication and Community Engagement |

| RHB | = | Regional Health Bureau |

| RRT | = | Rapid Response Team |

| SNNPR | = | Southern Nations and Nationalities People Region |

| SITREP | = | Situational Report |

| SOP | = | Standard Operating Procedure |

| TOR | = | Term Of Reference |

| TWG | = | Technical Working Group |

| WHO | = | World Health Organization |

| UNICEF | = | United Nation International Children’s Emergency Fund |

| USAID | = | United State Agency for International Development |

| VHF | = | Viral Hemorrhagic Fever |

| VRAM | = | Vulnerable Risk Assessment and Mapping |

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due these data mainly contain countries’ secret health policies and strategies but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

YA, IA, NA, AM, YM, MA, CA, BM, BR, TG, EW, DT, YA, DA, JA, NS, AF, YA, DA, ZD, YF, and MT have different experiences in conducting qualitative research, have participated in all parts of the work, including data collection and tools development, facilitated fieldwork logistics, analyzed and interpreted the data, assisted/contributed in translation, transcription, and analysis, and participated in reviewing the manuscript and preparing the draft manuscript. ZD provided special assistance and contribution to data analysis, thereby helping in the drafting process. Finally, all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are strongly indebted to those who engaged from the inception of this document to the final work. Without the commitment, these coauthors’ accomplishment of this manuscript would have been impossible. We thank the Ethiopian Public Health Institute for facilitating the accomplishment of this research project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yonas Assefa Tufa

Yonos Assefa Tufa have been engaged in different types of Qualitative and Quantitative research methodologies and also as a program coordinator I have experience in coordinating, leading, and managing major public health emergencies. Likewise, almost all Authors have different experiences in conducting qualitative research and participated in all parts of the work, including data collection, and tools development, facilitated fieldwork logistics, analyzing and interpreting the data; and assisted/contributed in translation, transcription, and analysis and participated in reviewing the manuscript and prepared the draft manuscript. And finally, all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Amarasinghe, A., Kuritsky, J. N., Letson, G. W., & Margolis, H. S. (2011). Dengue virus infection in Africa. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 17(8), 1349–15. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1708.101515

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute. (2022). National Arboviral Diseases Surveillance and response Guideline. Addis Ababa.

- The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Public Health Emergency Management (PHEM) Guidelines. Second Ed Addis Ababa July. 2021

- Ferreira, G. L. C. (2012). Global dengue epidemiology trends. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo, 54(18), 5–6. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0036-46652012000700003

- Khormi, H. M., & Kumar, L. (2011). Modelling dengue fever risk based on socioeconomic parameters, nationality and age groups: GIS and remote sensing-based case study. The Science of the Total Environment, 409(22), 4713–4719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.08.028

- Rigau-Perez, J. G., Vorndam, A. V., & Clark, G. G. (2001). The dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever epidemic in Puerto Rico, 1994-1995. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 64(1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.67

- Siqueira, J. B., Martelli, C. M., Maciel, I. J., Oliveira, R. M., Ribeiro, M. G., Martelli, C. M. T., Souza, W. V., Cardoso, D. D. P., Moreira, B. C., & Siqueira, J. B. (2004). Household survey of dengue infection in Central Brazil: Spatial point pattern analysis and risk factors assessment. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 71(5), 646–651. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2004.71.646

- Soumyajit, B., Gautam, A., & Goutam, K. (2013). Pupal productivity of dengue vectors in Kolkata, India: Implications for vector management. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 137(3), 549–559.

- WHO, Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases. (2010). World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2009). Dengue guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and control (New Edition ed.). WHO and tropical disease research.