Abstract

: Large inequalities in health exist between indigenous and non-indigenous populations worldwide. Indigenous populations have poorer health outcomes than their non-Indigenous counterparts do. This study aimed to examine child and maternal health vulnerability among the indigenous population in the country. The data for the present study was extracted from the fourth round of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-IV), which was conducted from 2015–16. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate the predicted prevalence of child and maternal morbidities in the social group. Social stratification is a major determinant of health inequality in a country’s indigenous and non-indigenous populations. Compared to non-indigenous women, indigenous women have a higher risk of asthma, cancer, and heart disease. Similarly, in the indigenous community, children are more vulnerable to stunting, wasting, and being underweight, mostly because they belong to the poorest economic households. The spatial analysis shows that the north-eastern state of Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Arunachal Pradesh was a higher prevalence of women’s asthma and heart diseases and central regions have a higher prevalence of child stunting, wasting, and infant mortality. The disparities in health between indigenous and non-indigenous populations are expanding owing to the distribution of various types of resources, demographic factors, and socioeconomic position. There is a need for policies and programs, especially for Scheduled Tribes, to promote their well-being in general, but also to reduce the child and maternal morbidity of the most vulnerable indigenous groups.

1. Introduction

Health vulnerability among indigenous populations is a significant global issue in the world. There are more than 370 million indigenous people worldwide who live across all regions in at least 70 countries (Willis et al., Citation2006). Poverty, malnutrition, overcrowding, poor hygiene, environmental contamination, and the prevalence of illnesses are all linked to poor health in the indigenous population. According to a 2009 report on world indigenous peoples, indigenous peoples have poorer health, are more likely to have disabilities and lower quality of life, and die younger than their non-indigenous counterparts (DESA, Citation2009). Indigenous peoples’ suboptimal health and health disparities between indigenous and non-indigenous populations reflect a basic failure to secure the freedom of indigenous people to fully develop their human, social, economic, and political potential (Sen, Citation1999). Importantly, there are universal health and economic differences between indigenous and non-indigenous people (Bristow et al., Citation2003; Stephens et al., Citation2005). According to an increasing number of studies, more than 20% of Cambodia’s indigenous under-five children suffer from malnutrition, with 52% of those stunted and underweight in growth (Bramley et al., Citation2004; Gracey, Citation2007; McCreery, Citation2012). In Nepal, the difference in life expectancy between indigenous and non-indigenous people is as high as 20 years (Pact, Citation2016). The earlier study investigated the health divide among the indigenous and non-indigenous groups due to differences in socioeconomic well-being and distribution of resources in the community which significantly contributes to the excess morbidity in the indigenous population group compared to the general population (Kate, Citation2001). The study indicates that extreme poverty is significantly more prevalent among indigenous peoples than non-indigenous groups, and is rooted in other factors, such as a lack of access to education and social services, destruction of indigenous economies and socio-political structures, forced displacement, armed conflict, and the loss and degradation of their customary lands and resources.

Indigenous peoples are variously called Indigenous, Aboriginal, tribal, or minority groups or peoples (Stephens et al., Citation2005). Poor definition of indigenous identification contributes to the marginalization of groups and inadequate data for their numbers, health, and socioeconomic circumstances. In India, this group has been classified by the official government as “schedule tribes”. The Indian government identifies communities as scheduled tribes based on a community’s “‘primitive traits, distinctive culture, shyness with the public at large, geographical isolation and social and economic backwardness’” (India Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Citation2004), with substantial variations in each of these dimensions with respect to different scheduled tribe communities (Basu, Citation2000). While “‘scheduled tribes’” is an administrative term adopted by the Government of India, the term “‘Adivasis’” (meaning “‘original inhabitants’” in Sanskrit) is often used to describe the different communities that belong to scheduled tribes (Subramanian et al., Citation2006, Citation2009). In India, over 84 million people belong to 698 communities which are constituting 8.2% of the population identified as members of scheduled tribes (India Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Citation2004; Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Citation2001). Compared to the national average schedule, tribes are much more vulnerable to disease, both communicable and non-communicable diseases, including tuberculosis, malaria, leprosy, and infant and maternal mortality rates. These groups are also exposed to higher risks of inadequate food intake (Ghosh & Bharati, Citation2005), poor hygiene (Neufeld et al., Citation2005), tobacco and alcohol consumption, and the lack of proper birth registration, which limits the access of indigenous communities living in remote areas to healthcare (Dolla et al., Citation2006; Meher, Citation2007; Nanda & Tripathy, Citation2005; Sathish et al., Citation2012)

Individual socioeconomic status is a major determinant of disparities in indigenous health, especially for infants and mothers. The heavy burden of different types of practices and infectious diseases among infants and children is mainly due to poor living conditions, inadequate nutrition, and poor hygiene and sanitation (Carville et al., Citation2007; Currie & Brewster, Citation2001; Gracey & King, Citation2009). Because of these environmental conditions, some of these diseases include skin infections, acute and chronic ear disease, dental caries, trachoma, diarrheal diseases, parasite infestations, upper and lower respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, and viral and bacterial infections affecting the nervous system. In addition, universal vaccination is often inaccessible to indigenous populations, especially those that belong to remote areas (Menzies & McIntyre, Citation2006).

Similarly, Indigenous women experience more severe health problems because they are disproportionately affected by natural disasters and armed conflicts, and are often denied access to education, land property, and other economic resources (Health Canada, Citation2005). Furthermore, indigenous women have higher experiences with sexual and reproductive health problems. Many Indigenous mothers are unprepared for pregnancy (Franks et al., Citation2006). They married at an early age and had been pregnant at a young age many times and, consequently, were at high risk of complications to themselves or their infants. These problems are closely linked to the violation of basic rights resulting from extreme poverty, vulnerability, and poor health conditions in indigenous communities. Many Indigenous women, especially those in poor countries, have little or no access to basic clinical staff and facilities that should be part of their routine care before, during, and after pregnancy (Gracey & King, Citation2009). Another study suggested that transmigration to urban areas increased the risk of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS, in indigenous populations (Gracey & King, Citation2009). Thus, maternal HIV infection affects infants and young children, increasing the risk of perinatal mortality, transplacental transmission of the virus, and the consequences of probable premature maternal death. From this perspective, this study examines the patterns of maternal and child health vulnerability among indigenous populations in India.

2. Data and methods

2.1. Data

The data for the present study was extracted from the fourth round of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-IV), which was conducted from 2015–16. The NFHS is a large-scale, cross-sectional, multi-round survey conducted in a nationally representative sample of households throughout India under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. The NFHS is an important large-scale demographic and health survey in India that provides sufficient information about population, fertility, mortality, family planning, health, healthcare utilization, and nutritional status.

2.2. Sampling design

NFHS-4 used a multistage stratified sampling as part of which the census enumeration blocks (CEBs) in urban areas and villages in rural areas were the primary sampling units (PSUs). Probability Proportional to Size (PPS) sampling was used to select the PSUs. The content and coverage of the survey have widened over time. In NFHS 4, the questions on screening for and diagnosis of particular diseases were asked of women aged 15–49 years. Detailed information is available in the National Report (International Institute for Population Sciences IIPS and ORC Macro, Citation2017).

2.3. Target population and sample size

Our target population in the study is indigenous women aged 15–49 years and children 0–5 years age. The NFHS covered the district-level information corresponding to households based on a sample of 1,315,617 children born to 699,686 women aged 15–49 years old from 601,509 households. With regards to the indigenous population, the present study has taken 667,074 women in the 15–49 age group and 52,199 children aged 0–5 years, from the five years preceding the survey respectively. NFHS women questionnaire included questions on self-reported asthma, heart diseases, cancer, and diabetes among women aged 15–49 years. The household response rates for eligible women were consistently above 90 % NFHS survey.

2.4. Outcome variable

The outcome variables in the present study were maternal and child health. Regarding maternal health, the study includes the self-reported presence of asthma, heart disease, cancer, and diabetes. The questions asked in NFHS questionnaires: “Has women ever been diagnosed with asthma, heart diseases, cancer, and diabetes?” and questions also asked related to treatment-seeking behavior i.e. are you taking medicine for asthma, heart diseases, cancer, and diabetes? If both the response is yes then only we considered that the indigenous women currently suffering from the particular diseases. To measure the prevalence of diseases, we reconstruct a dichotomous variable (“1” and “0”) from the set of variables; where “1” is considered as “women suffering from at least one disease” and “0” is considered as “women not suffering from any diseases” receptively.

Child health includes stunting (height for age), wasting (weight for height), underweight (weight for age), and infant mortality rate. The nutritional indicator of stunting is chronic nutrition, wasting is an acute form of malnutrition and underweight is a composite and a long-time undernourishment indicator. Stunting and wasting were defined for children 0–59 months of age whose height for age and weight for height Z score was minus two standard deviations below the median of the reference population. While underweight is considered in the children in the age group, 0–59 months whose weight for age Z score is minus two standard deviations below the median of the reference population. These two indicators’ Z scores were computed using the WHO-recommended reference pollution (Multicentre, Citation2006). Furthermore, infant mortality was assigned a value of 1 if the child died before 12 months and 0 if the child was alive at least until 12 months of age.

2.5. Covariates variables

The covariate variables utilized in this study can be broadly grouped into two categories socio-economic and bio-demographic. The socioeconomic variables included in the models were the mother’s education (No education, Primary; Secondary, and Higher), marital status (Never married; Married; Widow; Divorced and Separated), residence (Urban and Rural), wealth status (Poorest; Poorer; Middle; Richer and Richest), mother’s exposure to media (Radio, Television and Newspaper, as exposed; not exposed), alcohol consumption, and smoking consumption (Yes; No) of the household head. The bio-demographic variables included in the models were the mother’s age at birth (15–19; 20–24; 25–29; 30–34; 35–39; 40–45 and 45–49 years), birth interval (less than 24 months, 24 months or longer), birth order (1, 2, and 3+), birth weight (<2.5 kg and >2.5 kg), and sex of child (male and female).

2.6. Statistical and spatial analysis

In the present study, Bivariate and multivariate analyses were performed. The bivariate level involved comparing various child and maternal health with socioeconomic and bio-demographic variables. The life table method was used to estimate infant mortality in the analysis.

Descriptive analysis was followed by multivariate analysis to examine the significant effect of maternal and child health indicators after controlling for the variables among the indigenous population. Binary logistic regression was used for the different indicators of maternal and child health. The analysis was performed using STATA version 14.1. QGIS (version 3.16) was used to show the spatial variations among indigenous and non-indigenous populations in the study area.

3. Result

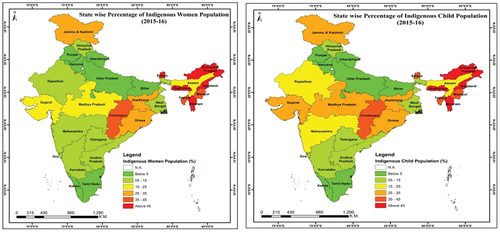

Table shows the state-wise distribution of indigenous women and child populations in India in 2015–16. The total indigenous women and child population of the country were 21.04% and 19.06%. The highest percentage of indigenous women population was found in Mizoram (96.9%), followed by Meghalaya (96.18%), Nagaland (95.21%), and Arunachal Pradesh (81.46%). In the northeastern states, the highest populations are covered by indigenous people as compared to any other state in the country (Figure ). Apart from the northeastern states, in the central region of Chhattisgarh (37.83%) and eastern region of Odisha (27.29%) were the highest percentage of indigenous population found in the country. In contrast, the lowest percentage of indigenous populations were found in Punjab (0.15%) and Haryana (0.44%), followed by southern states Tamil Nadu (1.82 %), Kerala (2.7 %), and Andhra Pradesh (5.85%) respectively. The same pattern was also observed for the indigenous child population. While the highest population was found in Meghalaya (98.03%) and the lowest in Punjab (0.12%) respectively.

Table 1. State-wise indigenous population in India, 2016

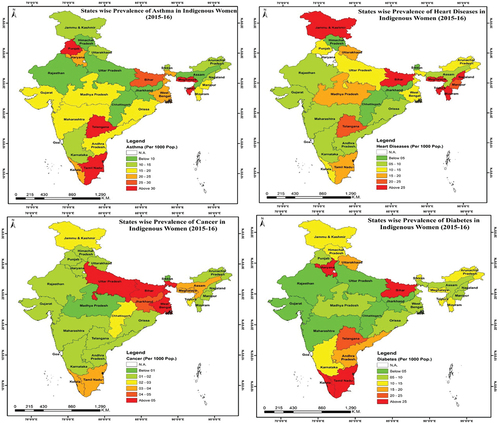

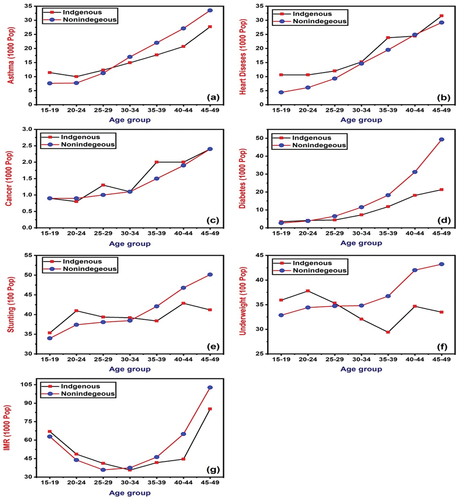

Table depict the prevalence of different type of non-communicable diseases among the indigenous and non-indigenous per 1000 women in the county in 2015–16. The prevalence of Asthma among indigenous and non-indigenous were varied across different demographic and socio-economic characteristics. The prevalence of asthma was higher in the age group above 35 years for both populations. In asthma, prevalence was higher in urban residents as compared to rural residents among the non-indigenous group. The differences were narrowed in higher education and wealth quintile among these groups. Those groups who have daily exposure to mass media, they are reported more asthma prevalence as compared to those who had not exposed to mass media. Lifestyle behavior factors like alcohol and smoking consumption were highly affected by the asthma prevalence of both groups. On the contrary prevalence of heart diseases and cancer was higher among the indigenous group as compared to non-indigenous groups. The risks of these diseases were increasing with increasing the age above 35 years. It’s made up of the “J” shape diagram. Where the age group 45–49 years was a higher prevalence of heart diseases and cancer among the indigenous group as compared to those below 25 years groups in the same population in the county respectively (Figure ). Education plays a dominant role in any kind of communicable disease. For example, people with higher education with lower prevalence of cancer and heart diseases than those with no and below primary education. Those who have belonged to the poorest and poorer households they are suffering the different types of heart diseases and cancer as compared to those who belonged to the richest and richer households. These differences are widening among the indigenous vs. non-indigenous population due to economic inequity in the community of the country. For those people who continuously taken alcohol and smoking consumption, the risk of heart disease and cancer prevalence was higher than those who had not taken any kind of alcohol and smoking consumption. This prevalence was also higher among the indigenous group as compared to the non-indigenous group in the country. Furthermore, the prevalence of diabetes was also heterogeneous among these populations due to different demographic and socio-economic characteristics. Although the prevalence is also higher among the non-indigenous group than the indigenous group in the country. There are spacious differences in diabetes prevalence among the indigenous and non-indigenous populations. This could be explained by different lifestyle behavior, socioeconomic quintile, and lack of physical exercise among the indigenous population. Exposures to mass media (television, radio, and newspaper) are increasing the awareness of people about their health. Thus, the non-indigenous group visits the health center and checkups and also more and report the diabetes prevalence than the indigenous people respectively.

Figure 2. Prevalence of maternal and child health among the indigenous and non-indigenous population with their age group- (a) asthma; (b) heart diseases; (c) cancer; (d) diabetes; (e) stunting; (f) underweight; (g) IMR.

Table 2. Differences in prevalence of non-communicable diseases per 1000 women among the indigenous and non-indigenous group population in India, 2015–16

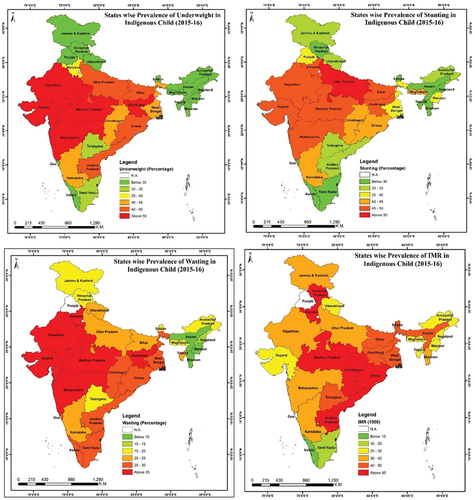

Table presents the percentage of stunting, wasting, underweight, and infant mortality rate per 1000 live births among the indigenous and nonindigenous population in the country in 2015–16. The differences in stunting and underweight prevalence in children age group below 5 years were negligible among the indigenous and non-indigenous groups in the country. Those mothers who had given birth in the below 19 age group had a higher prevalence of stunting as compared who had given birth in 20–24 years (Figure ). Similarly, the birth after 35 years was increasing the prevalence of stunting children in the family. Those mothers given birth in less than 24 months of birth interval had a higher risk of stunting than those who had given birth in more than 24 months of birth interval. The increasing birth order also increases underweight children among the mother in the indigenous population. The prevalence rate of malnutrition in children was higher in rural residences as compared to urban residences in the country. But the children belonged to non-indigenous families in urban residences was a higher prevalence of stunting than indigenous family respectively. The mother’s education plays an important role in child health care, those mothers who complete higher education led to delay marriage and given birth lower prevalence of stunting children as compared to those who had no and below primary education. The children who belonged to the richest household quintile had a lower prevalence of stunting and wasting than those who belonged to the poorest household family. Those mothers are exposed to mass media, and the prevalence rate of malnutrition in their children is lower than those who have not been exposed to mass media. The mother frequently had taken alcohol and smoked during the pregnancy the prevalence rate of stunting was also higher than those who had not taken any alcohol and smoked. The frequency was higher in the indigenous population than the non-indigenous population because of awareness of maternal and child health. Similarly, the result also observed in Infant mortality, below mother age at birth, higher birth order, below education, poorest household quintile, high alcohol, and smoking consumption were contribute higher infant mortality rate as compared to other factors respectively.

Table 3. Percentages of stunting, wasting, underweight, and infant mortality rate per thousand children among the indigenous group population India, 2015–16

Table shows the odds ratio of different types of non-communicable diseases among indigenous women in India from 2015–16. The result shows that risks of asthma, heart disease, and diabetes were higher among the indigenous women as compared to non-indigenous women with statically significant. The risks of all non-communicable diseases increased with increases the women’s age. For example, the women age group of 45–49 years 2.59 times, 3.69 times, 4.23 times, and 4.67 times were at higher risk of these diseases than the age group of 20–24 years with statically significant at 95 percent confidence level. The risk of asthma, heart disease, and cancer were more than one-time higher in rural residences, while the risk of diabetes was 0.86 times lower in rural residences than in urban residences among indigenous women, with statistical significance. Women with higher education had lower risks of developing these diseases than those who had completed primary education. Another interesting finding is that those women who belonged to the richest household were at higher risk of these diseases compared to those who belonged to the poorest household with a 95 percent statistical significance. The reverse result could be explained by the different lifestyle behaviors and standards of living in the richest background family. Those indigenous women were frequently taken alcohol and smoking the risk of non-communicable diseases higher as compared to those who had not taken any kind of alcohol and smoking consumption with statically significant.

Table 4. Odd’s ratio of non-communicable diseases among the indigenous women in India, 2015–16

Table presents the odds ratios of stunting, wasting, and underweight among the children in indigenous families in the study. The result shows children belonged to indigenous households in India were significantly high likely to be underweight, stunted, and wasted compared to children belonging to non-indigenous households with statically significant. Indigenous women who had given birth in the age group of 20–24 had a lower risk of stunting, being underweight, and wasting as compared to those who had given birth in the age group of 15–19 years. A similar pattern was also found after the age group of 35 years, childbirth women age more than 35 years increased the risks of child malnutrition among the indigenous family with statically significant. Those women given birth in more than 24 months of the preceding interval reduced the risk of child stunted and underweight by 26%, and 14% respectively. The increase in birth orders simultaneously increases the risk of child malnutrition in indigenous families. A child’s birth weight of more than 2.5 kg had a significantly lower risk of child malnutrition. The risk of child malnutrition was lower in females as compared to male children in the indigenous family. The risk of child malnutrition including stunting, wasting, and being underweight was higher among the indigenous family in a rural residence without statically significant. The higher educated women reduced risks of child stunted and underweight by 40% and 41% with statically significant. The children who belonged to richer and richest household family was at a lower risk of child stunting and being underweight as compared to those had belonged to poorer and poorest background families with statically significant respectively. Those women exposed to mass media is better awareness of their child malnutrition and also reduced the risks of child stunting and underweight 0.89 times and 0.90 times than those women not exposed to mass media. Those Indigenous women who frequently took alcohol and smoking consumption during pregnancy increased the risks of their child malnutrition than those who had not exposure to any alcohol and smoking consumption during pregnancy with statically significant in the study respectively. Similar results were observed for infant mortality (Table ). The results of the logistic models indicate that infant mortality is relatively higher among the indigenous family. For example, delayed age at mother birth, higher birth order, less educated, male child, alcohol, and smoking consumption of mother have significantly increased the risk of infant mortality in the country.

Table 5. Odds ratios of child stunting, wasting, underweight and infant mortality among the indigenous population in India, 2015–16

3.1. State-wise prevalence of maternal and Child health vulnerability

Figure shows the prevalence of maternal health vulnerability among the indigenous Indian population. The map shows that the different types of maternal health issues, such as asthma, heart diseases, cancer, and diabetes, varied across states among indigenous women. The highest asthma prevalence was found in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, Telangana, northeastern state of Meghalaya, Tripura, and the western states of Punjab. The lower prevalence zones of asthma in the northern and central parts of India include Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Himachal Pradesh. The prevalence of heart diseases is more clustered in the northern state of Jammu and Kashmir and the northeastern states of Meghalaya, Tripura, Mizoram, and Nagaland. A higher prevalence of cancer was observed, mainly in the central and eastern parts of India. The highest-performing states in terms of cancer among indigenous women include Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, and Jharkhand. In terms of diabetes prevalence, the most vulnerable states were Kerala and Tamil Nadu, followed by Bihar and Haryana. In the central region, the prevalence was lower than that in other regions (Appendix- Table ).

Figure shows the map representing the state-wise variation in child malnutrition (stunting wasting, and underweight) and infant mortality in India. A higher concentration of underweight children was observed mainly in the central and western parts of India. The poorest performing regions in terms of underweight children included Gujarat (52.8%), Madhya Pradesh (52.4%), Rajasthan (51.7%), and Maharashtra (51.4%). While In terms of children, stunting varied from 53% to 23 % from Uttar Pradesh to Himachal Pradesh. Child stunting and wasting were more prevalent in the central region than in the southern region. Infant mortality clustering from high mortality in the central, eastern, and northern parts of India. The major states with high infant mortality included Haryana (70/1000), Chhattisgarh (66/1000), Madhya Pradesh (58/1000), and Himachal Pradesh (52/1000). It is clear from the table (Appendix- Table ) that child malnutrition and infant mortality are relatively high in central, eastern, and a few parts of northern India. However, states where child malnutrition is low are clustered along the southern and northeastern regions of India.

4. Discussion

Our analysis has two major findings related to the patterns of health vulnerability among indigenous peoples in India. First, there are substantial differences in maternal health such as asthma, heart diseases, cancer, and diabetes between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples; the non-communicable diseases with asthma, heart diseases, and cancer are disproportionately greater for indigenous peoples, while diabetes, is much more concentrated among non-indigenous groups. There are also other parochial differences in child malnutrition and mortality between indigenous and non-indigenous people. The distribution of different types of resources, demographic factors, and socioeconomic status in indigenous and non-indigenous populations widened the gap in health inequalities between these two groups. The relative excess of non-communicable diseases among indigenous women was greatest for the age group of over 35 years, and the differences were relatively small in the age group of less than 25 years. This finding favors an interpretation that focuses on the importance of socioeconomic status over one that views indigeneity as an intrinsic risk factor (Subramanian et al., Citation2004, Citation2005). Furthermore, the differential attenuation in the health gap for indigenous women across life stages may suggest that socioeconomic status plays an important role in the burden of health inequality. The minor magnitude of socioeconomic differentials in malnutrition and mortality between indigenous and non-indigenous populations are also the greatest among mothers giving birth in younger and older age groups. This result might be explained by socio-environmental factors important for child health, such as maternal education, household wealth quintile, unequal access to health care, and the patterning of health-related behaviors, including alcohol and smoking consumption.

Furthermore, the excessive use of alcohol and smoking consumption is one of the important findings for high diabetes prevalence among non-indigenous women in the study as well as its contribution to accounting for excess child malnutrition and infant mortality. This lifestyle behavior among indigenous populations is linked to the process of colonization (Frank et al., Citation2000) and reflects Western culture (Gaiser, Citation1984; Seale et al., Citation2002) which may have a direct effect on the community. The prior study mentioned that the prevalence of tobacco and alcohol consumption among Scheduled Tribe men was quite high (more than 80%) in states like West Bengal, Bihar, Mizoram, and Odisha (Day, Citation2018).

Another interesting finding of this study is that there are substantial heterogeneities in the prevalence of diabetes among indigenous and non-indigenous women. Differential educational attainment and household wealth quintiles are major producers of health-related heterogeneity between indigenous and non-indigenous populations. This finding might explain the social and economic well-being creating health differences between indigenous groups and other population groups. However, economic inequality within indigenous groups is lower than that in non-indigenous groups. The distribution of different types of resources widened the gap between indigenous and non-indigenous groups. Thus, non-indigenous women are less physically active and continuously consume fast food, resulting in a greater prevalence of diabetes compared with non-indigenous populations (Pact, Citation2016). Nonetheless, as expected, the analysis of the respective contributions of the major socioeconomic factors shows that the concentration of poverty and lack of education among the Scheduled Tribes contributes significantly to the excess morbidity observed in this group compared with the general population (Haddad et al., Citation2012).

Similarly, non-communicable diseases, such as cancer and heart disease, have a higher level of vulnerability among indigenous women than among non-indigenous women. Such chronic diseases and their risk factors need to be countered by the promotion of healthy lifestyles, changes in food habits, encouragement of physical activity and sport, discouragement of cigarette smoking and alcohol and drug misuse, and fostering physical and emotional wellness (Leggatt & Frazer, Citation2007; Strong et al., Citation2006). Unless these changes occur, chronic diseases will spread more widely as more indigenous people adopt sedentary lifestyles. Stress or psychosocial adversity in these individuals may contribute to this vulnerability, as indigenous populations have not experienced improved life and work opportunities despite benefiting from increased education opportunities (Maybury-Lewis, Citation2002). People have different social positions, and biological factors are fully associated with chronic stress, which contributes to social gradients in the risk of coronary diseases and other morbidities (Brunner, Citation1997). Psychosocial factors also directly affect health-related behaviors, such as smoking, diet, alcohol consumption, and physical activity, which also play an important role in blood pressure regulation and increase the prevalence of cancer and heart diseases (Hemingway & Marmot, Citation1999).

Another important second finding in the study is the poor nutritional health issues such as stunting, wasting, underweight, and infant mortality among indigenous children in the country. Health vulnerability among indigenous children is one of the most important and challenging issues in nations. Indigenous people suffer from malnutrition because of environmental degradation and contamination of the ecosystems in which indigenous communities have traditionally lived, loss of land and territory, and decline in the abundance or accessibility of traditional food sources (Ghosh & Bharati, Citation2005). These changes in the traditional diet, combined with other lifestyle changes, have resulted in widespread malnutrition among indigenous people. A recent study conducted by Van de Poel and Speybroeck on decomposing (Van de Poel & Speybroeck, Citation2009) malnutrition inequalities in India found that more than one-third of the malnutrition gap was attributable to differences in the effects of health determinants after controlling for a large set of explanatory variables. These variables are poverty, insufficient food, lack of healthcare facilities, lower maternal education, and early age at marriage and childbearing. Substandard nutrition in infants and young children can be associated with maternal ill-health and malnutrition, or both, which can negatively affect pregnancy and predispose to premature birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth retardation (Knibbs & Sly, Citation2014).

5. Conclusion

The overall conclusion of this study suggests that there is a wide gap in health inequality between indigenous and non-indigenous populations. The presence of socioeconomic inequalities in health, even within indigenous populations, was a key finding of our study. Indigenous people have higher rates of physical, mental, and emotional illnesses, injuries, disability, and earlier and higher mortality than their non-Indigenous counterparts. An earlier study conducted in an Australian indigenous group indicated that the mortality gap between the indigenous group and the other population is greater than the disability gap, such as when they are fallen ill, they are more likely to die than non-indigenous groups (Horton, Citation2006). This discrepancy is probably caused by a lack of awareness, inadequate access to clinical care, frequent alcohol consumption, smoking, and tobacco consumption. Child malnutrition differentials within indigenous and non-indigenous groups were much more similar in this study. However, the overall health divide gap between the two groups is widening because of the differential socio-economic well-being between indigenous and non-indigenous groups (John, Citation2005). To tickle the issue necessities some policies and programs to benefit the Scheduled Tribes need to be tailored to not only promote the well-being of tribes in general but also to target the specific needs of each tribe, needs that differ both in nature and severity (Harfield et al., Citation2018).

6. Limitations and strengths of the study

Our study has some limitations. Firstly the present study was based on self-reported information by the indigenous population which could be recall bias. As NFHS data does not carry out the laboratory experiment, therefore it cannot be directly compared with clinical data. Second, the NFHS data did not cover the physical barrier such as transport facility, distance from the health center, and quality of cigarettes and alcohol which may have resulted in variations between diseases. And thirdly, data does not provide information on the types of food such as vegetarian and non-vegetarian which has a strong association with non-communicable diseases. Despite all this, the study provides reliable information on research designs and standardized data collection processes and awareness of diseases among the indigenous population are significant strengths of the study.

Authors’ Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments and analyzed the data: U.D and N.K; Wrote the paper: U.D, N.K, B.C, and P.K.

Availability of data and material

This research work was performed based on secondary data, which are freely available upon request at the International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), India website (Source of data: http://rchiips.org/NFHS/index.shtml).

Ethics approval & consent to participate

This research does not have an ethical code because it was performed based on secondary data that is freely available upon request at the IIPS, India website (Source of data: http://rchiips.org/NFHS/index.shtml); thus, the author does not require any ethical clearance and consent to participate.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ujjwal Das

Ujjwal Das were involved in the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the data; the drafting of the paper, revising it critically for intellectual content.

Nishamani Kar

Nishamani Kar were involved in the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of the data; the drafting of the paper, revising it critically for intellectual content.

Barkha Chaplot

Barkha Chaplot were involved in the design, analysis and interpretation of the data; revising it critically for intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published.

Pawan Kumar

Pawan Kumar were involved in the design, analysis and interpretation of the data; revising it critically for intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published.

References

- Basu, S. (2000). Dimensions of tribal health in India. Health and Population Perspectives and Issues, 23(2), 61–29.

- Bramley, D., Hebert, P., Jackson, R., & Chassin, M. (2004). Indigenous disparities in disease-specific mortality, a cross-country comparison: New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and the United states. The New Zealand Medical Journal (Online), 117(1207), U1215.

- Bristow, F., Nettleton, C., & Stephens, C. (Eds.). (2003). Utz’wach’il: Health and well being among indigenous peoples. Health Unlimited.

- Brunner, E. (1997). Socioeconomic determinants of health: Stress and the biology of inequality. BMJ, 314(7092), 1472. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7092.1472

- Carville, K. S., Lehmann, D., Hall, G., Moore, H., Richmond, P., De Klerk, N., & Burgner, D. (2007). Infection is the major component of the disease burden in aboriginal and non-aboriginal Australian children: A population-based study. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 26(3), 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.inf.0000254148.09831.7f

- Currie, B. J., & Brewster, D. R. (2001). Childhood infections in the tropical north of Australia. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 37(4), 326–330. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1754.2001.00661.x

- Day, S. (2018). Equal status for indigenous women—sometime, not now: The Indian act and bill S-3. Canadian Woman Studies/Les Cahiers De La Femme.

- DESA. (2009). State of the World’s indigenous peoples. United Nations.

- Dolla, C. K., Meshram, P., Verma, A., Shrivastav, P., Karforma, C., Patel, M. L., & Kousal, L. S. (2006). Health and morbidity profile of Bharias-a primitive tribe of Madhya Pradesh. Journal of Human Ecology, 19(2), 139–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2006.11905868

- Frank, J. W., Moore, R. S., & Ames, G. M. (2000). Historical and cultural roots of drinking problems among American Indians. American Journal of Public Health, 90(3), 344. https://doi.org/10.2105/2Fajph.90.3.344

- Franks, P. W., Looker, H. C., Kobes, S., Touger, L., Tataranni, P. A., Hanson, R. L., & Knowler, W. C. (2006). Gestational glucose tolerance and risk of type 2 diabetes in young Pima Indian offspring. Diabetes, 55(2), 460–465. https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-0823

- Gaiser, J. (1984). Smoking among Maoris and other minorities in New Zealand. World Smoking & Health, 9(1), 7–18. PMID: 12179600.

- Ghosh, R., & Bharati, P. (2005). Women’s status and health of two ethnic groups inhabiting a periurban habitat of Kolkata city, India: A micro-level study. Health Care for Women International, 26(3), 194–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330590917753

- Gracey, M. S. (2007). Nutrition‐related disorders in indigenous Australians: How things have changed. Medical Journal of Australia, 186(1), 15–17. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00779.x

- Gracey, M., & King, M. (2009). Indigenous health part 1: Determinants and disease patterns. The Lancet, 374(9683), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60914-4

- Haddad, S., Mohindra, K. S., Siekmans, K., Màk, G., & Narayana, D. (2012). “Health divide” between indigenous and non-indigenous populations in Kerala, India: Population based study. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-390

- Harfield, S. G., Davy, C., McArthur, A., Munn, Z., Brown, A., & Brown, N. (2018). Characteristics of indigenous primary health care service delivery models: A systematic scoping review. Globalization and Health, 14(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-018-0332-2

- Health Canada. (2005). Aboriginal health. Retrieved June 12, 2016, from http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/pubs/system-regime/2005-blueprint-plan-aborauto/fs-fi-03-eng.php

- Hemingway, H., & Marmot, M. (1999). Evidence based cardiology: Psychosocial factors in the aetiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease: Systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 318(7196), 1460. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.318.7196.1460

- Horton, R. (2006). Indigenous peoples: Time to act now for equity and health. The Lancet, 367(9524), 1705–1707. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68745-X

- India Ministry of Tribal Affairs. (2004) The national tribal policy (draft). New Delhi: India Ministry of tribal Affairs. Retrieved September 26, 2006, from http://tribal.nic.in/finalContent.pdf

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. (2017). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), India, 2015-16

- John, R. M. (2005). Tobacco consumption patterns and its health implications in India. Health Policy, 71(2), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.08.008

- Kate, S. L. (2001). Health problems of tribal population groups from the state of Maharashtra. Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, 55(2), 99–108.

- Knibbs, L. D., & Sly, P. D. (2014). Indigenous health and environmental risk factors: An Australian problem with global analogues? Global Health Action, 7(1), 23766. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v7.23766

- Leggatt, G. R., & Frazer, I. H. (2007). HPV vaccines: The beginning of the end for cervical cancer. Current Opinion in Immunology, 19(2), 232–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2007.01.004

- Maybury-Lewis, D. (2002). Indigenous peoples, ethnic groups and the state (2nd ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

- McCreery, R. (2012). Promoting indigenous-led economic development: Why par ties should consult the undrip. Indigenous Law Bulletin, 8(3), 16–19. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.017368485227518

- Meher, R. (2007). Livelihood, poverty and morbidity: A study on health and socio-economic status of the tribal population in Orissa. Journal of Health Management, 9(3), 343–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/097206340700900303

- Menzies, R., & McIntyre, P. (2006). Vaccine preventable diseases and vaccination policy for indigenous populations. Epidemiologic Reviews, 28(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxj005

- Multicentre, W. H. O. (2006). Reference G. Acta Paediatrica, 95, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.tb02378.x

- Nanda, S., & Tripathy, M. (2005). Reproductive morbidity, treatment seeking behaviour and fertility: A study of scheduled caste and tribe women. Journal of Human Ecology, 18(1), 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2005.11905812

- Neufeld, K. J., Peters, D. H., Rani, M., Bonu, S., & Brooner, R. K. (2005). Regular use of alcohol and tobacco in India and its association with age, gender, and poverty. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 77(3), 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.022

- Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner. (2001). Total population, population of scheduled castes and scheduled tribes and their proportions to the total population.

- Pact, A. I. P. (2016). Situation of the right to health of indigenous peoples in Asia. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- Sathish, T., Kannan, S., Sarma, P. S., Razum, O., & Thankappan, K. R. (2012). Incidence of hypertension and its risk factors in rural Kerala, India: A community-based cohort study. Public Health, 126(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2011.11.002

- Seale, J. P., Shellenberger, S., Rodriguez, C., Seale, J. D., & Alvarado, M. (2002). Alcohol use and cultural change in an indigenous population: A case study from Venezuela. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 37(6), 603–608. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/37.6.603

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. A. Knopf.

- Stephens, C., Nettleton, C., Porter, J., Willis, R., & Clark, S. (2005). Indigenous peoples’ health—why are they behind everyone, everywhere? The Lancet, 366(9479), 10–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66801-8

- Strong, K., Mathers, C., Epping-Jordan, J., & Beaglehole, R. (2006). Preventing chronic disease: A priority for global health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 35(2), 492–494. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyi315

- Subramanian, S. V., Nandy, S., Irving, M., Gordon, D., & Smith, G. D. (2005). Role of socioeconomic markers and state prohibition policy in predicting alcohol consumption among men and women in India: A multilevel statistical analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 83(11), 829–836. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16302039

- Subramanian, S. V., Nandy, S., Kelly, M., Gordon, D., & Smith, G. D. (2004). Patterns and distribution of tobacco consumption in India: Cross sectional multilevel evidence from the 1998-9 national family health survey. BMJ, 328(7443), 801–806. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7443.801

- Subramanian, S. V., Perkins, J. M., & Khan, K. T. (2009). Do burdens of underweight and overweight coexist among lower socioeconomic groups in India? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 90(2), 369–376. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.27487

- Subramanian, S. V., Smith, G. D., Subramanyam, M., & Hales, S. (2006). Indigenous health and socioeconomic status in India. PLoS Medicine, 3(10), e421. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030421

- Van de Poel, E., & Speybroeck, N. (2009). Decomposing malnutrition inequalities between scheduled Castes and tribes and the remaining Indian population. Ethnicity & Health, 14(3), 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557850802609931

- Willis, R., Jackson, D., Nettleton, C., Good, K., & Mugarura, B. (2006). Health of indigenous people in Africa. The Lancet, 367(9526), 1937–1946. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68849-1

Appendix

Table A1. States wise prevalence of non-communicable diseases in women and child health among the indigenous population in India, 2015–16