?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

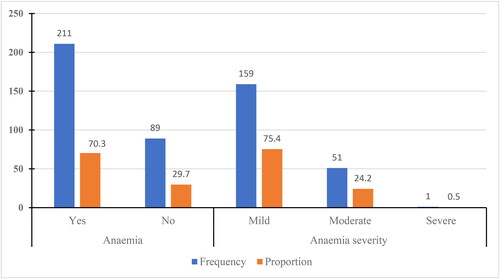

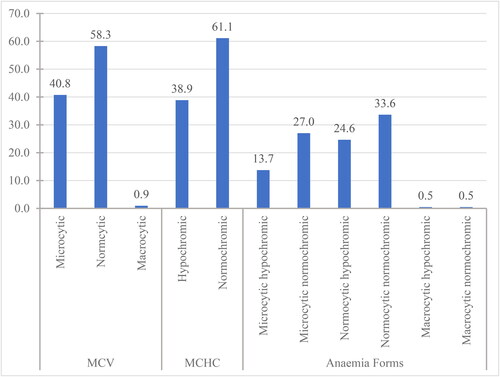

Although anaemia is a common life-threatening condition among pregnant women, particularly those in low-income countries, literature remains very limited in Ghana in general and particularly in the Madina La-Nkwantanang Municipality of the Greater Accra Region, where no studies have been done. This study, therefore, assessed anaemia in pregnant women attending the Pentecost Hospital in the La-Nkwantanang Municipality, Ghana. This cross-sectional study conveniently recruited 300 Ghanaian pregnant women attending the Madina Pentecost Hospital for antenatal care. A structured questionnaire was administered to obtain data on sociodemographics (age, marital status, level of education, occupation and religion) and knowledge level of anaemia. Blood samples were taken for an automated complete blood count (CBC). SPSS software version 26 and GraphPad Prism were used for the statistical analysis. The prevalence rate of anaemia was 211/300 (70.3%). 159 (75.4%) of the anaemic subjects presented with a mild anaemia form, 51(24.2%) presented with a moderate form, and 1(0.47%) presented with severe form. Normocytic normochromic anaemia was the dominant anaemia type (33.6%), followed by microcytic normochromic anaemia (27.0%), and then normocytic hypochromic (24.64%). Pregnant women within their third trimester recorded the highest incidence rates of both normocytic normochromic 34 (47.89%) and mild types 71 (44.65%) of anaemia. The prevalence of anaemia among pregnant women is overwhelmingly high with a preponderance towards those in their third trimester. As such, high-risk pregnant women should be well-monitored to prevent exacerbating the condition.

Keywords:

Subjects:

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Anaemia is a significant public health concern affecting the lives of about 1.62 billion individuals worldwide (De Benoist et al., Citation2008). Anaemia is defined as a decrease in circulating red blood cell or hemoglobin concentration (less than 11.0 g/dl) which reduces the oxygen-carrying capacity of the red blood cells rendering them incapable to meet the physiological body requirements (World Health Organization, Citation2001). According to the WHO, anaemia in pregnancy can be classified further into mild (10.0–10.9 g/dl), moderate (7.0–9.9 g/dl) and severe (less than 7.0 g/dl) (Goonewardene et al., Citation2012). It is associated with increased perinatal mortality, impaired cognitive development, and increased child morbidity and mortality (Dallman et al., Citation1991) and affects all ages of the population with its highest prevalence among children under five years of age and pregnant women (Balarajan et al., Citation2011; Salhan et al., Citation2012).

Over half (56%) of pregnant women in low and middle-income countries (LMIC) suffer from anaemia (Black et al., Citation2013), with the highest rates found in Sub-Saharan Africa (57%) (World Health Organization, Citation2008). A growing body of knowledge among previous authors suggests that the causes of anaemia in pregnancy are multifactorial with iron, folate, and other micronutrient deficiencies being the most common (Von Look et al., Citation2006; Zerfu & Ayele, Citation2013). However, in low and middle-income countries like Ghana, pathological conditions such as intestinal parasitic infections (Baidoo et al., Citation2010), malaria (Ouma et al., Citation2007), HIV infection (Völker et al., Citation2017) and haemoglobinopathies (Engmann et al., Citation2008) have been named to be major contributors to anaemia in pregnancy. Notwithstanding, Alemu and colleagues have also postulated a range of overarching socio-economic and cultural factors such as culture, religious food taboos malnutrition, and low intake of iron among others (Alemu & Umeta, Citation2015).

Generally, anaemia in pregnant women has been reported to have serious adverse outcomes including high maternal death, impaired mental development in children, increased risk of fetal growth retardation, low birth weight, premature delivery, and perinatal mortality (Pinto & Albuquerque, Citation2015; Tunkyi & Moodley, Citation2015). In the same vein, maternal complications like cardiac failure, sepsis, post-partum haemorrhage, maternal mortality, and fetal complications such as intrauterine growth restriction and preterm birth have also been mentioned to be implications of anaemia in pregnancy (Lin et al., Citation2018; Sifakis & Pharmakides, Citation2000).

Owing to these facts, there has been a shift of attention among previous authors to probe the prevalence of anaemia and its associated risk factors among children, adolescents, and pregnant women in Ghana and across the globe. Despite all these, Ghana is still known to be among the top countries in Africa with a high burden of anaemia in pregnancy (Dhs, Citation2013). Acheampong et al. (Citation2018) have conducted a study in anaemia among pregnant women in selected part of Greater but not in La Nkwantanang Municipality. It is against this background that the present study sought to assess anaemia in pregnant women in their various trimesters in the La Nkwantanang Municipality.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and study site

This study is a hospital-based cross-sectional study conducted at the Pentecost Hospital in the La-Nkwantanang Municipality, Ghana, between October 2021 and February 2022.

The Pentecost Hospital previously known as Alpha Medical Center began operation in May 1997 at Madina. Pentecost Hospital is accredited by the National Health Insurance Scheme Board and is the Municipal Hospital for La Nkwantanang-Madina. The hospital accepts referred cases from clinics and health centres in the municipality and other areas. The Pentecost Hospital provides general medical services and specialized services like Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Ophthalmology, Endoscopy, Renal dialysis, and Dental health.

2.2. Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was sought and obtained from the University of Health and Allied Sciences Research Ethics Committee (UHAS REC) with certificate number, UHAS-REC A.11[60] 21-22. Written consent was obtained from the management of the Madina Pentecost Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the study was commenced.

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All pregnant women seeking healthcare during the period under review at the Pentecost Hospital and consented to be part of the study were enrolled. Pregnant women who were severely ill or had a history of chronic disorders or bad obstetrics were excluded, as well as those who planned to give birth in other hospitals or refused to participate.

2.4. Sample size estimation

Using the average monthly attendance of pregnant women in the Pentecost Hospital, an average of 405 pregnant women visits the Hospital for antenatal clinic in a month. Thus, for one month period of data collection, the total expected study population will be 405. The sample size was determined using Israel’s formula for calculating sample size for proportions at 95% confidence level and 0.05 level of precision (Israel GD, Citation1992).

Where n = sample size, N = population size, e = margin of error (0.05)

n = 201.2

Per Israel’s formula, the sample size calculated was 201.2. However, we extrapolated it to 300 to account for missing data and to increase the statistical power of the study. Convenient sampling technique was employed.

2.5. Data collection

Structured questionnaire was used to obtain data on socio-demographic characteristics and knowledge levels of anaemia among the participants. Knowledge of anaemia was assessed by asking questions regarding causes, effects and sources of information regarding anaemia. Blood sample (3 ml) was taken aseptically into EDTA tube. The sample was put on a rack and transferred to a blood roller mixer for CBC estimation using URIT 5250 Automated Haematology Analyzers (Guilin Urit Electronic Group Co., Ltd, China). The protocol for the estimation was based on the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.6. Definition of anaemia

We defined anaemia in pregnancy as haemoglobin concentration less than 11.0 g/dl according to the WHO criteria (World Health Organization, Citation2001).

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data was entered into Microsoft office excel 2016 spreadsheet. Descriptive and inferential analysis was done using SPSS version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism 8.0.1 (GraphPad LLC, San Diego, California, USA). Categorical outcomes were expressed as frequency and proportions. Chi-square test was used to test the association between sociodemographic characteristics and anaemia. Pearson chi-square was used as p-value. All p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants

In this study, a total of 300 participants who consented to be part of this study were enrolled. Out of the total 300 participants, the majority 175 (58.3%) of the respondents were within the age brackets of 20–30 years whiles 11(3.7%) were within the less than 20 years age group. More than 70% of the respondents were married whereas 64 (21.3%) participants were single. Among the total participants, 70 (23.3%) of respondents had obtained tertiary education and 96 (32.0%) had obtained secondary education. However, 25 (8.3%) respondents had no formal education. It was also observed in this study that, 234 participants were Christians whiles 63 were Muslims representing 78.0% and 21.0% respectively. The majority 189 (63.0%) of the respondents were non-formal workers. Out of the total 300 expectant mothers, the majority 128 (42.7%) were in their third trimester whereas the least fraction 79 (26.3%) of the respondents were in their first trimester (see ).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants.

3.2. Prevalence of anaemia

In this study, it was observed that the prevalence rate of anaemia among the study participants stood at 70.3%. Among the participants with anaemia, 159 (75.4%) presented with a mild form of the condition whereas 51 (24.2%) of the respondents presented with a moderate form (See ).

3.3. Prevalent forms of anaemia

Regarding MCV, the study revealed a higher proportion of normocytosis among the anaemic participants followed by microcytosis with prevalence of 58.3% and 40.8% respectively. From the MCH and MCHC majority of the participants (61.1%) presented with normochromasia whiles 38.9% of the respondents presented with hypochromasia. Normocytic normochromic anaemia was the most prevalent anaemia type observed among 33.6% of the anaemic participants followed by microcytic normochromic anaemia with a rate of 27.0%. However, microcytic hypochromic anaemia was recorded among 13.7% of the study respondents ().

3.4. Prevalence of anaemia among the various trimesters of pregnancy

In this study, it was shown that majority of the study participants with anaemia were within their 3rd trimester with prevalence of 45.50%. The study also revealed an increasing burden of anaemia moving from the 1st trimester to the 3rd trimester. Study participants within their 3rd trimester recorded the highest prevalent rates of both mild and moderate types of anaemia. However, severe anaemia was only observed in a single respondent within the 2nd trimester. All forms of anaemia were predominantly seen among participants in their third trimester except for macrocytic hypochromic and macrocytic normocytic anaemia which were only observed among study respondents in their second trimester ().

Table 2. Incidence of anaemia among the various trimesters of pregnancy.

3.5. Knowledge of participants about anaemia

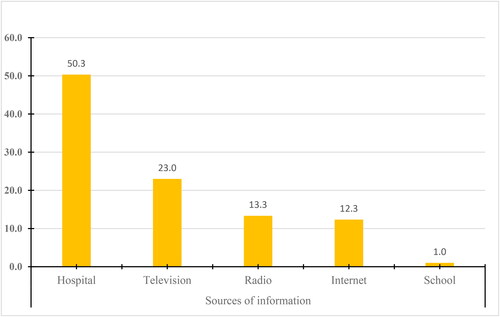

We observed that, 266/300(88.67%) of the respondents had knowledge about anaemia in pregnancy. 216 respondents were on food supplement whiles 84 respondents were not on any food supplement giving proportions of 72.00% and 28.00% respectively. The majority of the respondents 136(45.33%) indicated that fatigue is a common symptom of anaemia they know whereas 89(29.67%) of the respondents stated that pale face is the anaemia symptom they know. However, the least fraction of the study participants 18(6.00%) revealed that they are aware of spoon-shaped nails as a symptom of anaemia. With regards to the causes of anaemia, more than 60% of the study participants responded that anaemia is caused by a lack of iron in food whiles only 2.67% of the respondents stated that it is due to pregnancy ().

Table 3. Knowledge of pregnant women about anaemia.

3.6. Sources of information

Among the study participants, majority, which was approximately half (50.3%) of them, acquired their knowledge about anaemia from the hospital through health workers. For mass media as source of information about anaemia, television accounted for almost one-fifth (23.0%), followed by radio (13.3%), and then the internet (12.3%). Only 1.0% of the respondents obtained their knowledge of anaemia from the school ().

3.7. Association between demographic factors and anaemia

The Chi-square analysis shows that religion (p = 0.0368) is the only demographic factor that is significantly associated with anaemia among the study participants ().

Table 4. Association between demographic factors and anaemia.

4. Discussion

In pregnancy, anaemia is an important public health problem as it impacts not only the pregnant woman but also significantly affects the unborn child (Khan et al., Citation2006). Anaemia in pregnancy has been noted to be associated with birth complications, adverse foetal outcomes, maternal morbidity and mortality (Sifakis & Pharmakides, Citation2000). Evidence shows that severe anaemia is an important independent risk factor for increased prevalence of foetal death, pre-eclampsia, pre-term labour, heart failure and maternal sepsis (Sifakis & Pharmakides, Citation2000). Statistics derived from earlier studies show that 34–56% of pregnant women in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) have anaemia and Ghana is among the countries in Africa with a high prevalence of anaemia in pregnancy (Acheampong et al., Citation2018; Engmann et al., Citation2008; Nonterah et al., Citation2019). The current study therefore aimed at assessing the burden of anaemia among selected pregnant women in the Madina Pentecost Hospital in La Nkwantanang Municipality.

In this study, cases of anaemia were observed in 211 (70.3%) of the study participants. This finding is consistent with a previous report by Ngimbudzi et al. (83.5%) among pregnant women in Tanzania (Ngimbudzi et al., Citation2021). Previous authors argued that the etiology of anaemia is multifactorial and the precise mechanism of anaemia in pregnancy is not known. However, reports from earlier studies suggest a critical role of iron deficiency resulting from prolonged negative iron balance, which may be due to inadequate dietary iron intake or absorption, increased needs for iron during pregnancy, and increased iron losses as a result of worm infestation and infections (Camaschella, Citation2015; Melku et al., Citation2014). Another study proposed the role of folate (Von Look et al., Citation2006) and other micronutrient deficiencies (Zerfu & Ayele, Citation2013), parasitic infections (Ouma et al., Citation2007), and HIV infection (Völker et al., Citation2017) causing anaemia in pregnancy. Notwithstanding, the overall prevalence rate of anaemia observed in the current study is higher compared to the rates recorded by Acheampong et al. (Citation2018) (51.0%) in Ghana (Acheampong et al., Citation2018), Kara et al., (46.3%) in Tanzania (Kara et al., Citation2020), Asrie et al., (25.2%) in Ethiopia (Asrie, Citation2017) and Al-Aini et al., (25%) in Yemen (Al-Aini et al., Citation2020). A plausible reason for this disparity in prevalence could be due to differences in ethnicity and sample sizes across the studies.

Regarding the classification of anaemia among expectant mothers based on severity, the current study revealed that the majority of 159 (75.4%) presented with a mild form of the condition, which is a common feature in pregnancy anaemia. This finding is consistent with similar studies conducted in different parts of Ghana (Acheampong et al., Citation2018; Anlaakuu & Anto, Citation2017; Ouma et al., Citation2007), Africa (Melku et al., Citation2014; Tunkyi & Moodley, Citation2015), and the Middle East (Al-Aini et al., Citation2020). In an attempt to explain the health significance of the classes of anaemia, a previous study postulated that; mild anaemia may not affect the index pregnancy but reduce maternal iron stores and affect subsequent pregnancies, moderate anaemia on the hand may present with significant signs and symptoms which may interfere with the daily life of the pregnant woman whiles severe anaemia is associated with poor maternal and fetal outcome including increased incidence of foetal death, pre-eclampsia, pre-term labour, heart failure and maternal sepsis (Kidanto et al., Citation2009; Sifakis & Pharmakides, Citation2000).

Generally, anaemia may manifest in various forms in circulation owing to down-regulation in some red cell parameters in association with low or normal levels in others. The current study tried to demonstrate the common morphological characterization of anaemia among expectant mothers. According to the red cell parameters (MCV, MCH, MCHC) normocytic normochromic blood picture was the most common morphological type of anaemia found in this study (). The characteristic pattern of anaemia observed in the current study corresponds with previous reports (Melku et al., Citation2014; Nwizu et al., Citation2011; Tunkyi & Moodley, Citation2015). The observation of this blood picture among the study participants is suggestive of haemolytic anaemias which causes normocytic normochromic morphologies. Anaemia of haemolytic causes could probably be due to infectious diseases such as malaria infestation, which is endemic in the country and is a common cause of febrile illness among pregnant women. The low incidence of microcytic hypochromic (iron deficiency) and macrocytic hypochromic (vitamin A and B12 deficiency) might reflect the remarkable efforts of the diet unit as the majority (72.0%) of the participants are counselled and put on food supplements (). Of particular note is the gestational age disparity in anaemia burden, with cases more pronounced among women in their third trimester (96, or 45.5%) (). This could be because, as pregnancy progresses, tissue fluid increases over cell mass, resulting in a physiological haemodilution, this results in reduced haemoglobin especially in the last trimester of pregnancy (Wemakor, Citation2019). The current observation of pronounced anaemia in women in their third trimester aligns with earlier studies by Wemakor et al., in Ghana (Wemakor, Citation2019), Nwizu et al., in Nigeria (Nwizu et al., Citation2011), and Melku et al., in Ethiopia (Melku et al., Citation2014). Although several previous studies have reported this gestational age bias of burden of anaemia, there are no substantial explanations for this regular occurrence among pregnant women. However, an earlier report extrapolates that it could be due to the fact the third trimester is a stage during which haematopoietic nutrients (namely: iron, cobalamin, hematopoietic factors, and other micronutrients) demand is greatly increased (Wemakor, Citation2019).

Additionally, previous authors have recorded higher rates of anaemia among different age categories, with some observing the highest vulnerability among individuals below 30 years and others reporting higher rates among over 30 years individuals in Asia (Lestari et al., Citation2018) and Africa (Acheampong et al., Citation2018; Wemakor, Citation2019). In the present study, it was observed that the overall prevalence rate of anaemia was high among women below 20 years and those above 40 years, although the difference was not statistically significant (). This observation contradicts with the previous reports of Melku et al. (Citation2014), Tibambuya et al. (Citation2019), and Wemakor (Citation2019) who recorded significantly high anaemia burden among the younger and elderly individuals in different sub-populations. Across the globe, several studies have posited a wide range of overarching factors associated with anaemia among pregnant mothers. These factors include but are not limited to gestational age, parity, occupational status, intestinal parasitological infection, HIV infection, poverty, and malnutrition (Asrie, Citation2017; Gebreweld & Tsegaye, Citation2018; Melku et al., Citation2014; Nonterah et al., Citation2019). For this reason, the current study also tried to determine the association between anaemia and sociodemographic factors of the study participants. The findings of the present study revealed that there was no significant association between anaemia and any of the demographic factors except religion (). This may suggest that certain religious beliefs or practices and adherence factors during pregnancy predispose women to developing anaemia. It is therefore recommended that more studies be conducted to confirm the finding of the current study and to establish the precise religious beliefs or practices favouring anaemia surge in order to help reduce the burden of anaemia in pregnancy.

4.1. Limitations

This study has limitations, in that it was conducted in a single hospital-based clinic and used convenience sampling, which prevents generalization of the findings to the entire population. It focused mainly on sociodemographics and did not consider other important factors such as obstetric factors, hematological factors, and dietary factors. Further studies are needed to identify specific causes of anaemia in pregnant women and enable proper management.

4.3. Conclusion

The study found that the prevalence rate of anaemia among the study participants was overwhelmingly high. Despite national interventions such as supplementation during ANC (antenatal care) and directly observed treatment (DOT), the high prevalence persisted. Anaemia was particularly prevalent among participants in their third trimester of pregnancy. The study highlighted that anaemia rates were high among both younger women (below 20 years) and elderly women (above 40 years).

Author contributions

Richard Vikpebah Duneeh: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation, methodology; project administration; supervision; and writing-review and editing. Wina Ivy Ofori Boadu: Investigation; methodology; supervision; and writing-review and editing. Lois Tekutey Narh: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; writing-original draft preparation; and writing-review and editing. Joseph Frimpong: Formal analysis; methodology; writing-original draft preparation; and writing-review and editing. Abdul-Wahab Mawuko: Methodology; investigation; supervision; and writing-review and editing. John Gameli Deku: Investigation; methodology; supervision; and writing-review and editing. Kofi Mensah: Methodology; investigation; supervision; and writing-review and editing. Charles Nkansah: Methodology; investigation; supervision; and writing-review and editing. Samuel Kwasi Appiah: Investigation; software; visualization; and writing-review and editing. Felix Osei Boakye: Methodology; investigation; supervision; and writing-review and editing. Enoch Odame Anto: Formal analysis; methodology; investigation; supervision; and writing-review and editing. Lilian Antwi Boateng: Methodology, investigation; and writing-review and editing. Benedict Sackey: Methodology, investigation; and writing-review and editing. Otchere Addai-Mensah: Conceptualization; data curation; investigation, methodology; project administration; supervision; and writing-review and editing.

QUESTIONNAIRE.docx

Download MS Word (15.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the study participants, hospital personnel, research assistants, and volunteers who all helped make the study a success.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and can be requested from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Richard Vikpebah Duneeh

Richard Vikpebah Duneeh, Degrees: A PhD student with the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi-Ghana. Hold an MPhil in Haematology and BSC. Medical Laboratory Science from KNUST Obtained a Higher National Diploma in Science Laboratory Technology from the Accra Polytechnic. Fellowship – I am a fellow of the West African Postgraduate College of Medical Laboratory Science (WAPCMLS), Haematology. Affiliation: Haematology Unit, Medical Laboratory Sciences Department, School of Allied Health Sciences, University of Health and Allied Sciences, Ho-Volta Region, Ghana Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology Allied Health Professions Council (AHPC), Ghana Ghana Association of Medical Laboratory Scientists (GAMLS). Research Interests: Haematological malignancies Haemoglobinopathies: sickle cell disease and thalassaemias and other anaemias Transfusion Science, transfusion transmissible infections Malaria Parasite: identification, speciation and parasite density General Haematology.

Wina Ivy Ofori Boadu

Wina Ivy Ofori Boadu, is a Medical Laboratory Scientist with over 16 years post qualification experience in haematology, clinical chemistry, parasitology, bacteriology and blood transfusion science. she has extensive knowledge in quality control, standardization and calibration of medical laboratory equipment as well as hospital laboratory management. She holds a PhD in chemical pathology and currently a lecturer at the department of medical diagnostics, KNUST. Prior to her appointment as a lecturer, she was the head of the diagnostic laboratory of the University Health Service, KNUST.

Lois Tekutey Narh

Lois Tekutey Narh, Degrees: An MLS.D student with University of Development Studies(UDS), Tamale- Ghana. Holds a BSC. Medical Laboratory Sciences from the University of Health and Allied Sciences (UHAS), Ho- Ghana. Obtained a Diploma in Medical Laboratory Sciences from College of Health Kintampo- Ghana. Affiliations: Allied Health Professional Council (AHPC), Ghana. Ghana Association of Medical Laboratory Scientist (GAMSL). Medical Laboratory Professional Workers Union (MELPWU). Research Interests: Haemoglobinopathies and Transfusion Science.

Joseph Frimpong

Joseph Frimpong is a medical laboratory scientist who currently works as a Teaching/Research assistant at the Department of Medical Diagnostics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. MLS Joseph Frimpong does research in global health, metabolic syndrome, and type-2 diabetes mellitus.

Abdul-Wahab Mawuko

Abdul-Wahab Mawuko, PhD, MSc, PgD, B.Tech, MLT.C (Medical Microbiologist), Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, School of Allied Health Sciences, University of Health and Allied Sciences, Ho. Affiliated with the Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, School of Allied Health Sciences of the University of Health and Allied Sciences and Biomedical Sciences Research.

John Gameli Deku

John Gameli Deku, holds PhD in Clinical Microbiology. He is affiliated to the Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, School of Allied Health Sciences of the University of Health and Allied Sciences. His research interest is antimicrobial resistance.

Kofi Mensah

Kofi Mensah, Emails/Affiliations: [email protected] [email protected] Department of Haematology, School of Allied Health Sciences, University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Faculty of Health Sciences and Education, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Nigeria ORCID IDs: 0000-0002-2238-2797 DEGREES: MPhil., (Ph.D. Candidate) POSITION AND RESEARCH INTEREST: Lecturer (Haematology) Malignancies, Haemoglobinopathies, Haemostasis.

Charles Nkansah

Charles Nkansah Emails/Affiliations: [email protected] Department of Haematology, School of Allied Health Sciences, University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Faculty of Health Sciences and Education, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Nigeria ORCID IDs: 0000-0001-6986-9976 DEGREES: MPhil. . (Ph.D Candidate) Position and Research Interest: Lecturer (Haematology) Haemopoiesis; Anaemia; Blood Cell Disorders; Blood Transfusion Science; Haemostasis; Cancer Biology; Malaria.

Samuel Kwasi Appiah

Samuel Kwasi Appiah, Emails/Affiliations: [email protected] Department of Haematology, School of Allied Health Sciences, University for Development Studies, Tamale, Ghana Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Faculty of Health Sciences and Education, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Nigeria ORCID IDs: 0000-0003-1855-5840 DEGREES: MPhil., (Ph.D. Candidate) POSITION AND RESEARCH INTEREST: Lecturer (Haematology) Haemopoiesis, Haemoglobinopathies, Blood Disorders, Malignancies, ELISA, Malaria, Anaemia.

Felix Osei Boakye

Felix Osei Boakye Emails/Affiliations: [email protected] Department of Medical Laboratory Technology, Faculty of Applied Science and Technology, Sunyani Technical University, Sunyani, Ghana Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Faculty of Health Sciences and Education, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Nigeria ORCID IDs: 0000-0001-5126-7424 DEGREES: MPhil., (Ph.D. Candidate) POSITION AND RESEARCH INTEREST: Lecturer (Haematology) Haemovigilance; Haemostasis; Blood Cell Disorders; Malaria; Tuberculosis.

Enoch Odame Anto

Enoch Odame Anto is a Senior Lecturer of Medical Laboratory Science at the Department of Medical Diagnostics and Biomedical Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST). He is a Sessional Academic Teaching Staff and an Adjunct Lecturer at the School of Medical and Health Science, Edith Cowan University. Dr. Enoch Odame Anto has widespread research experience in global health, Women and Child Health, Chemical pathology- related metabolic, Histo-immunopathology, and infectious disease, which has led to over 100 peer-reviewed publications including articles, book chapters, abstract proceedings, and media publications. His research interests are in Medical Laboratory Science, Global Health, Chemical pathology-related metabolic and infectious diseases, Biochemical haematology, Histology, immunohistochemistry, and Women and Child health.

Lilian Antwi Boateng

Lilian Antwi Boateng has been an early career lecturer and researcher in the haematology and immunohaematology Unit of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana since 2012. She holds a PhD in transfusion medicine. Dr. (Mrs.) Lilian Antwi Boateng has research interest in the following fields: General Haematology; Blood group genetics/genotyping; and Red blood cell immuno-haematology.

Benedict Sackey

Benedict Sackey is lecturer of Haematology who joined the Department of Medical Diagnostics, KNUST in 2011 following 9yrs of working as Biomedical Scientist in the Department of Haematology at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital. He has considerable expertise in techniques for diagnosis of sickle cell diseases and Proficiency testing through training at Center for Disease Control, Atlanta, USA and NUPAD - School of Medicine Belo Horizonte, Brazil. He had worked with the Sickle Cell Foundation of Ghana since 2005 as Biomedical Scientist in the Clinical Laboratory Component and was appointed a member of National Technical Advisory Committee on Newborn Screening for Sickle Cell Disease in Ghana in 2010. His Research interest is in Haematological Cancers and Haemoglobinopathies in the areas of: Cancer biology and immunology; DNA damage response interactions in tumor microenvironment; and Systemic and Palliative Interventions in severity/complications of Sickle cell diseases.

Otchere Addai-Mensah

Otchere Addai-Mensah is an Associate Professor of Haematology, Immunology and Global Health in the Department of Medical Diagnostics, and the Vice-Dean of Students at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. Prof. Dr. Dr. Addai-Mensah has extensive experience in scientific research and general management, and has a number of publications in reputable journals to his credit. His research interests are in Infectious Diseases, Malariology, Biomedical Sciences, Immuno-epidemiology, Haematology, Immunology, Transfusion Medicine and Public Health.

References

- Acheampong, K., Appiah, S., Baffour-Awuah, D., & Arhin, Y. S. (2018). Prevalence of anaemia among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic of a selected hospital in Accra, Ghana. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research, 8(1), 1–10.

- Al-Aini, S., Senan, C. P., & Azzani, M. (2020). Prevalence and associated factors of anaemia among pregnant women in Sana’a, Yemen. Indian Journal of Medical Sciences, 72(3), 185–190.

- Alemu, T., & Umeta, M. (2015). Reproductive and obstetric factors are key predictors of maternal anaemia during pregnancy in Ethiopia: Evidence from demographic and health survey (2011). Anemia, 2015, 649815–649818. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/649815

- Anlaakuu, P., & Anto, F. (2017). Anaemia in pregnancy and associated factors: A cross sectional study of antenatal attendants at the Sunyani Municipal Hospital, Ghana. BMC Research Notes, 10(1), 402. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2742-2

- Asrie, F. (2017). Prevalence of anaemia and its associated factors among pregnant women receiving antenatal care at Aymiba Health Center, northwest Ethiopia. Journal of Blood Medicine, 8, 35–40. https://doi.org/10.2147/jbm.S134932

- Baidoo, S. E., Tay, S. C., Obiri-Danso, K., & Abruquah, H. H. (2010). Intestinal helminth infection and anaemia during pregnancy: A community based study in Ghana. Journal of Bacteriology Research, 2(2), 9–13.

- Balarajan, Y., Ramakrishnan, U., Ozaltin, E., Shankar, A. H., & Subramanian, S. V. (2011). Anaemia in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet (London, England), 378(9809), 2123–2135. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)62304-5

- Black, R. E., Victora, C. G., Walker, S. P., Bhutta, Z. A., Christian, P., de Onis, M., Ezzati, M., Grantham-McGregor, S., Katz, J., Martorell, R., & Uauy, R. (2013). Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet (London, England), 382(9890), 427–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60937-x

- Camaschella, C. (2015). Iron-deficiency anaemia. The New England Journal of Medicine, 372(19), 1832–1843. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1401038

- Dallman, R., Iron, P., Ziegler, I., Filer, E., & Filer, L. (1991). Present knowledge in nutrition. ILSI Press. Washington.

- De Benoist, B., Cogswell, M., Egli, I., & McLean, E. (2008). Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993-2005. WHO Global Database of Anaemia.

- Dhs, M. (2013). Demographic and health surveys. Measure DHS.

- Engmann, C., Adanu, R., Lu, T. S., Bose, C., & Lozoff, B. (2008). Anemia and iron deficiency in pregnant Ghanaian women from urban areas. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 101(1), 62–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.09.032

- Gebreweld, A., & Tsegaye, A. (2018). Prevalence and factors associated with anaemia among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Advances in Hematology, 2018, 3942301–3942308. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3942301

- Goonewardene, M., Shehata, M., & Hamad, A. (2012). Anaemia in pregnancy. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 26(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2011.10.010

- Israel GD. (1992). Determining sample size. University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agriculture Sciences, EDIS.

- Kara, W. S. K., Chikomele, J., Mzigaba, M. M., Mao, J., & Mghanga, F. P. (2020). Anaemia in pregnancy in Southern Tanzania: Prevalence and associated risk factors. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 24(3), 154–160. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2020/v24i3.17

- Khan, K. S., Wojdyla, D., Say, L., Gülmezoglu, A. M., & Van Look, P. F. (2006). WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet (London, England), 367(9516), 1066–1074. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68397-9

- Kidanto, H. L., Mogren, I., Lindmark, G., Massawe, S., & Nystrom, L. (2009). Risks for preterm delivery and low birth weight are independently increased by severity of maternal anaemia. South African Medical Journal = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif Vir Geneeskunde, 99(2), 98–102.

- Lestari S, Fujiati I, Keumalasari D, Daulay M, Martina SJ, Syarifah S, editors. (2018 The prevalence of anaemia in pregnant women and its associated risk factors in North Sumatera, Indonesia [Paper presentation]. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, IOP Publishing.

- Lin, L., Wei, Y., Zhu, W., Wang, C., Su, R., Feng, H., & Yang, H. (2018). Prevalence, risk factors and associated adverse pregnancy outcomes of anaemia in Chinese pregnant women: A multicentre retrospective study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), 111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1739-8

- Melku, M., Addis, Z., Alem, M., & Enawgaw, B. (2014). Prevalence and predictors of maternal anaemia during pregnancy in Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia: An institutional based cross-sectional study. Anemia, 2014, 108593–108599. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/108593

- Ngimbudzi, E. B., Massawe, S. N., & Sunguya, B. F. (2021). The burden of anaemia in pregnancy among women attending the antenatal clinics in Mkuranga District, Tanzania. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 724562. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.724562

- Nonterah, E. A., Adomolga, E., Yidana, A., Kagura, J., Agorinya, I., Ayamba, E. Y., Atindama, S., Kaburise, M. B., & Alhassan, M. (2019). Descriptive epidemiology of anaemia among pregnant women initiating antenatal care in rural Northern Ghana. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 11(1), e1–e7. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v11i1.1892

- Nwizu, E. N., Iliyasu, Z., Ibrahim, S. A., & Galadanci, H. S. (2011). Socio-demographic and maternal factors in anaemia in pregnancy at booking in Kano, northern Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 15(4), 33–41.

- Ouma, P., van Eijk, A. M., Hamel, M. J., Parise, M., Ayisi, J. G., Otieno, K., Kager, P. A., & Slutsker, L. (2007). Malaria and anaemia among pregnant women at first antenatal clinic visit in Kisumu, western Kenya. Tropical Medicine & International Health: TM & IH, 12(12), 1515–1523. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01960.x

- Pinto, D. C., & Albuquerque, F. G. (2015). Jul 12 Factors relating to iron deficiency anaemia in pregnancy: an integrative review. International Archives of Medicine, 159(8). https://doi.org/10.3823/1758

- Salhan, S., Tripathi, V., Singh, R., & Gaikwad, H. S. (2012). Evaluation of hematological parameters in partial exchange and packed cell transfusion in treatment of severe anaemia in pregnancy. Anemia, 2012, 608658–608657. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/608658

- Sifakis, S., & Pharmakides, G. (2000). Anemia in pregnancy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 900(1), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06223.x

- Tibambuya, B. A., Ganle, J. K., & Ibrahim, M. (2019). Anaemia at antenatal care initiation and associated factors among pregnant women in West Gonja District, Ghana: A cross-sectional study. The Pan African Medical Journal, 33, 325. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2019.33.325.17924

- Tunkyi, K., & Moodley, J. (2015). Prevalence of anaemia in pregnancy in a regional health facility in South Africa. South African Medical Journal = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif Vir Geneeskunde, 106(1), 101–104. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i1.9860

- Tunkyi, K., & Moodley, J. (2015). Prevalence of anaemia in pregnancy in a regional health facility in South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 106(1), 101–104. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i1.9860

- Völker, F., Cooper, P., Bader, O., Uy, A., Zimmermann, O., Lugert, R., & Groß, U. (2017). Prevalence of pregnancy-relevant infections in a rural setting of Ghana. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17(1), 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1351-3

- Von Look, P., Lincetto, O., & Fogstad, H. (2006). Iron and folate supplementation: Integrated management of pregnancy and childbirth (IMPAC) (Vol. 10). World Health Organization.

- Wemakor, A. (2019). Prevalence and determinants of anaemia in pregnant women receiving antenatal care at a tertiary referral hospital in Northern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(1), 495. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2644-5

- World Health Organization. (2001). The world health report 2001: mental health: new understanding new hope. In The World Health Report 2001: Mental health: New understanding new hope (pp. xviii–xv178).

- World Health Organization. (2008). World health statistics 2008. World Health Organization.

- Zerfu, T. A., & Ayele, H. T. (2013). Micronutrients and pregnancy; effect of supplementation on pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review. Nutrition Journal, 12(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-12-20