Abstract

Dysfunctional beliefs play an important role in the aetiology and maintenance of social anxiety disorder (SAD). Despite this—and the heightened salience of emotion in SAD—little is known about SAD patients' beliefs about whether emotions can be influenced or changed. The current study examined these emotion beliefs in patients with SAD and in non‐clinical participants. Overall, patients were more likely to hold entity beliefs (i.e., viewing emotions as things that cannot be changed). However, this group difference in emotion beliefs varied by emotion domain. Specifically, SAD patients more readily held entity beliefs about their own emotions and anxiety than about emotions in general. By contrast, non‐clinical participants more readily held entity beliefs about emotions in general than about their own. Results also indicated that even when controlling for social anxiety severity, patients with SAD differed in their beliefs about their emotions, and these beliefs explained unique variance in perceived stress, trait anxiety, negative affect, and self‐esteem.

The authors of this manuscript do not have any direct or indirect conflicts of interest, financial, or personal relationships or affiliations to disclose.

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is a chronic and debilitating condition. It is the fourth most common psychiatric disorder after major depression, substance use disorders, and specific phobias (Kessler et al., Citation2005). Patients with SAD experience marked fear or anxiety in social situations (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). As a result, they frequently demonstrate significant impairments at work (Bruch, Fallon, & Heimberg, Citation2003), school (Kashdan & Herbert, Citation2001; Schneier et al., Citation1994), and in friendships and intimate relationships (Montesi et al., Citation2012; Rodebaugh, Citation2009). Social anxiety is also associated with low self‐esteem (Schreiber, Bohn, Aderka, Stangier, & Steil, Citation2012) and poor overall quality of life (Simon et al., Citation2002).

Maladaptive beliefs in SAD

Cognitive models of SAD (Clark & Wells, Citation1995; Heimberg, Brozovich, & Rapee, Citation2010; Hofmann, Citation2007) have largely emphasised the role of maladaptive beliefs in the disorder's aetiology and treatment—particularly maladaptive beliefs about the probability and costs of performing poorly in social situations (Smits, Julian, Rosenfield, & Powers, Citation2012). For example, patients with SAD often believe they lack the necessary social skills to interact normally with others (Gaudiano & Herbert, Citation2003) and that behaving ineptly has disastrous consequences (Hofmann, Citation2004). They also hold excessively high standards for their social performance and believe their self‐worth is contingent on being positively evaluated (Clark & Wells, Citation1995; Wong & Moulds, Citation2011). In addition to research on probability and cost biases, researchers have also examined the role of more general dysfunctional beliefs in SAD. This includes maladaptive beliefs about one's appearance (Rapee, Gaston, & Abbott, Citation2009), and negative core beliefs about the self (e.g., I am unlovable; I don't fit in) (Boden et al., Citation2012; Schulz, Alpers, & Hofmann, Citation2008), as well as the role of negative imagery (Moscovitch, Gavric, Merrifield, Bielak, & Moscovitch, Citation2011). These maladaptive beliefs are believed to play an important role in SAD as they are thought to lead to—and perpetuate—exaggerated emotional reactivity and emotion dysregulation, including safety and avoidance behaviours, which all play a key role in the disorder (Clark, Citation2001; Clark & Wells, Citation1995; Hofmann, Citation2007).

Although there has been a good deal of work on probability and cost biases and on maladaptive self‐beliefs, one category of beliefs that has to date received very little attention in research on SAD concerns patients' beliefs about how much they can change or control their emotions. This is surprising as emotion beliefs have been presented as a key mechanism of change in cognitive models of the disorder (Hofmann, Citation2000, Citation2007), and many have called for research on their role in treatment (Hofmann, Citation2000, Citation2007; Manser, Cooper, & Trefusis, Citation2011; Tamir & Mauss, Citation2011). In the following sections, we present the research on emotion beliefs in non‐selected populations and their relevance for patients with SAD.

Beliefs about emotions in non‐selected populations

Research in non‐clinical samples has found that people differ in their beliefs about the fixed or malleable nature of emotions (De Castella et al., Citation2013; Tamir, John, Srivastava, & Gross, Citation2007). People holding entity beliefs believe emotions cannot really be changed or controlled. People holding incremental beliefs, on the other hand, view emotions as malleable and believe that people can learn to change the emotions they experience. Because these beliefs are often not consciously held, they have also been referred to as implicit beliefs or implicit theories (Dweck, Citation1999; Tamir et al., Citation2007).

Research with undergraduate students indicates that these beliefs have important associations with emotional health, social functioning, and well‐being. Entity beliefs about one's shyness (e.g., ‘my shyness is something about me that I can't change very much’) have been linked with greater avoidance behaviour in social situations, whereas people holding incremental beliefs exhibit more approach‐orientated behaviour despite their fears and are rated as more socially skilled, likeable, and talkative in conversation tasks by independent observers (Beer, Citation2002). In the context of beliefs about emotions, students holding entity beliefs report more emotion regulation difficulties, more negative and less positive emotional experiences, and reduced social support from their friends (Tamir et al., Citation2007). Recently, entity beliefs have also been linked in non‐clinical samples to stress and depression, as well as to lower levels of self‐esteem and poorer overall satisfaction with life (De Castella et al., Citation2013). Interestingly, people's beliefs about their ability to control their own emotions are a stronger predictor of these outcomes than their beliefs about the controllability of emotions in general (De Castella et al., Citation2013).

Beliefs about emotions in SAD

SAD is a particularly interesting clinical context for examining patients' beliefs about their emotions. Patients with SAD struggle with attending to, describing, expressing, and regulating their emotional experiences (Mennin, McLaughlin, & Flanagan, Citation2009; Werner, Goldin, Ball, Heimberg, & Gross, Citation2011) and frequently underestimate their control over external events (Leung & Heimberg, Citation1996). Barlow (Citation2000) argues that, for patients with SAD, repeated experience with uncontrollable events and aversive emotional reactions may also reinforce a belief that their emotions, in particular, are outside of their control. In a destructive cycle, this in turn perpetuates fear and avoidance of social situations. In support of this model, Hofmann (Citation2005) has found that among patients with SAD, a perceived lack of control over physical symptoms of anxiety and external threats partially mediates the link between catastrophic thinking and social anxiety. These findings point to the important role emotion beliefs may play in SAD. However, to date, researchers have not yet examined how patients with SAD differ from non‐clinical participants in their beliefs about their emotions and whether patients' emotion beliefs differ from more specific beliefs about their own emotions and their social anxiety.

The current study

The goal of the current study was to examine whether patients with SAD and non‐clinical participants differ in their beliefs about their emotions. We measured (1) general and (2) personal beliefs about emotions, as has been done in the non‐clinical literature (De Castella & Byrne, unpublished data; Tamir et al., Citation2007). We also assessed (3) more specific beliefs about social anxiety, which may be particularly important for patients with SAD. By assessing emotion beliefs in several different domains, we sought to examine whether people's beliefs about the controllability of emotions in general differed from their beliefs about the controllability of their own emotions and, more specifically, the extent to which they could change or control their social anxiety.

We predicted that patients with SAD would hold stronger entity beliefs about emotions than non‐clinical participants, and that this group difference would be maximal in the domain of one's own emotions and anxiety (Hypothesis 1). Furthermore, focusing on patients with SAD, we expected that, entity beliefs about emotions would be associated with higher levels of social anxiety, perceived stress, and trait anxiety (Hypothesis 2). We also predicted an entity theory of emotions would be associated with lower levels of well‐being (positive and negative affect, self‐esteem, and satisfaction with life) (Hypothesis 3). In these analyses, we also conducted hierarchical linear regressions to examine the extent to which patients' emotion beliefs explained unique variance in the dependent variables above and beyond what might already be explained by their existing level of social anxiety.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Participants were 75 patients (40 men, 35 women) who met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IV, American Psychiatric Association, Citation1994) criteria for a principal diagnosis of generalised SAD, and 42 non‐clinical participants (20 men, 22 women) with no history of current or past DSM‐IV psychiatric disorders. All participants were between 21 and 53 years of age (M = 33 years, standard deviation (SD) = 9 years) and were ethnically heterogeneous (55% Caucasian; 29% Asian; 7% Latino; 2% Filipino; 1% African American; 6% Other). There were no significant age, gender, ethnicity, or educational differences between patients and non‐clinical participants (all p values >.75).

Non‐clinical participants and patients with SAD both underwent extensive diagnostic screening prior to selection including survey and telephone screening as well as an in‐person diagnostic interview—the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule Lifetime Version for the DSM‐IV (Brown, DiNardo, & Barlow, Citation1994). Clinical psychologists conducted the interviews, which assessed current (and past) episodes of anxiety, mood, somatoform, and substance use disorders as well as patients' medical and psychiatric treatment history. Participants were recruited from 2007 to 2010 as part of a larger study on the neural substrates of emotion regulation in generalised SAD and its treatment with cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Because participants were part of a larger study using functional magnetic resonance imaging, they also had to be right handed and pass safety screening. They were excluded if they reported prior or current CBT, a history of medical disorders, head trauma, current pharmacotherapy, or psychotherapy.

Among patients, current Axis‐I co‐morbidity included 14 with generalised anxiety disorder, 5 with specific phobia, 3 with panic disorder, and 3 with dysthymic disorder. All other co‐morbidities were exclusion criteria. Thirty‐six patients reported past psychotherapy (i.e., ended more than 1 year ago), and 25 reported a past history of pharmacotherapy. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The overall design of the study and its main outcomes are reported elsewhere (Goldin et al., Citation2012).

Measures

Beliefs about emotions

General beliefs about the malleability of emotions were assessed with the four‐item Implicit Theories of Emotion Scale (Tamir et al., Citation2007). Two items measured incremental beliefs, e.g., ‘If they want to, people can change the emotions that they have’, and two measured entity beliefs, e.g., ‘The truth is, people have very little control over their emotions’. Participants were asked to rate their agreement on a 5‐point Likert‐type scale. For each of the emotion beliefs scales, incremental theory items were reverse scored, and all items were then summed so that higher scores reflected an entity theory and lower scores an incremental theory of emotions. Cronbach's alphas for all scales can be found in Table .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, Cronbach's alphas, means, and standard deviations for patients with social anxiety disorder (SAD, n = 75) and non‐clinical participants (NC, n = 42)

Personal beliefs about the malleability of emotions were assessed using the four‐item personal scale (De Castella et al., Citation2013). Unlike the general scale, each item reflects a first‐person claim about the extent to which one can change or control one's own emotions, e.g., ‘If I want to, I can change the emotions that I have’. Although no research exists on these general and personal beliefs in clinical samples, research in student samples indicates that the personal scale is reliable (α = .79) and explains greater variance in well‐being and psychological distress than the general emotion beliefs scale (De Castella et al., Citation2013).

Beliefs about the malleability of social anxiety were assessed using a new variant of the four‐item personal scale. Efforts were made to ensure items stayed closely aligned to the originals with each reflecting a first‐person claim about one's ability to change or control one's social anxiety. Items were as follows: ‘If I want to, I can change the social anxiety that I have’, ‘I can learn to control my social anxiety’, ‘The truth is, I have very little control over my social anxiety’, and ‘No matter how hard I try, I can't really change the social anxiety that I have’.

Stress and anxiety

Stress was measured with the four‐item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS‐4) (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, Citation1983). The PSS‐4 asks about the extent to which life situations are appraised as stressful over the past month (e.g., ‘I felt that difficulties were piling up so high that I could not overcome them’). Items are scored on a 4‐point Likert‐type scale ranging from 1 (rarely or none of the time) to 4 (most or all of the time). Summed scores range from 4 to 16. In non‐SAD clinical samples, the PSS‐4 has been shown to be internally consistent and reliable (Hewitt, Flett, & Mosher, Citation2012).

Trait anxiety was measured with the trait subscale of the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI‐T) (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, Citation1983). The STAI‐T is a widely used measure of clinical anxiety and assesses how patients ‘general feel’ e.g., ‘I worry too much over something that really doesn't matter’. Responses are scored on a 4‐point Likert‐type scale ranging from 0 (almost never) to 3 (almost always). Summed scores ranged from 20 to 80. Overall, the STAI‐T displays good convergent and discriminant validity, internal consistency, and retest reliability (Spielberger et al., Citation1983).

Social interaction anxiety was measured with the Social Interaction Anxiety Straightforward Scale (SIAS‐S, Rodebaugh, Woods, & Heimberg, Citation2007; Rodebaugh, Woods, Heimberg, Liebowitz, & Schneier, Citation2006). Based on the original 20‐item SIAS (Mattick & Clarke, Citation1998), the revised SIAS‐S excludes three reversed‐keyed items, reducing the scale to 17 straightforward items that measure social anxiety in social situations, dyads, and groups (e.g., ‘I have difficulty making eye‐contact with others’). Items are rated on a 5‐point Likert‐type scale ranging from 0 (Not at all characteristic or true of me) to 4 (Extremely characteristic or true of me). Summed scores ranged from 0 to 68. The SIAS‐S has demonstrated good internal consistency and construct validity, and research indicates that it is an improved measure of social interaction anxiety in clinical and non‐clinical samples (Rodebaugh et al., Citation2006, Citation2007).

Social anxiety was assessed with the self‐report version of the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) (Fresco et al., Citation2001). The LSAS is a commonly used clinical measure of social anxiety, and the clinician administered (Liebowitz, Citation1987) and self‐report versions yield equivalent results (Fresco et al., Citation2001). The scale consists of 24 items, which assess fear and avoidance of social (e.g., meeting strangers) and performance (e.g., taking a written test) situations during the past week. Participants rate their fear and avoidance on a 4‐point scale from 0 (no fear/avoidance) to 3 (severe fear or anxiety/usually avoid). Total scores, summing fear and avoidance ratings, range from 0 to 144. Research indicates the scale is reliable and displays good convergent and discriminant validity (Fresco et al., Citation2001; Ledley, Erwin, Morrison, & Heimberg, Citation2013).

Well‐being measures

Self‐esteem was assessed using the Rosenberg Self‐Esteem Scale (RSES, Rosenberg, Citation1965). The RSES is a widely used measure of global self‐esteem. It contains 10‐items rated on a 4‐point Likert‐type scale (summed scores ranging from 10 to 40). The scale demonstrates good convergent validity, test‐retest reliability, and internal consistency in research on social anxiety (Kuo, Goldin, Werner, Heimberg, & Gross, Citation2011).

Life satisfaction was measured using the five‐item Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS, Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, Citation1985). The SWLS is a commonly used measure of life satisfaction (e.g., ‘In most ways my life is close to ideal’). The SWLS has displayed high internal consistency, test‐retest reliability, as well as convergent and discriminant validity (Pavot & Diener, Citation2008). Items are rated on a 7‐point Likert‐type scale with total scores ranging from 5 to 35.

Positive and negative affect were assessed using the 20‐item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, Citation1988). The scale consists of two 10‐item subscales containing adjectives that assess positive (e.g., enthusiasm) and negative affect (e.g., irritable) over the last week. Responses are scored on a 5‐point Likert‐type scale with total scores ranging from 10 to 50. The scale is a widely used measure of positive and negative affect and displays excellent psychometric properties (Crawford & Henry, Citation2004; Watson et al., Citation1988).

Results

Means (M), SD, ranges, internal consistencies (α), and correlations among the three emotion belief domains and measures of clinical symptoms, anxiety, perceived stress, and well‐being are presented in Tables and .

Table 2. Correlations between measures for patients with social anxiety disorder (SAD, n = 75)

Hypothesis 1: Patients with SAD and non‐clinical participants

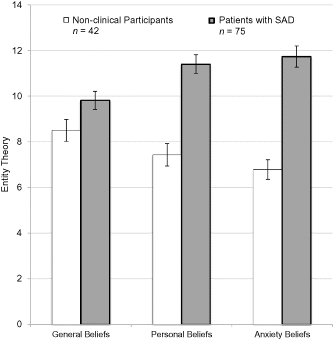

To examine whether patients with SAD differed from non‐clinical participants (NC) in their beliefs about emotions, we conducted a 2 group (SAD vs NC) × 3 belief domain (personal, general, anxiety) repeated‐measures analysis of variance. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, there was a significant main effect for group (F(1, 115) = 34.06, p < .001, R2 = .23) and a significant group × belief domain interaction (F(1, 115) = 29.25, p < .001, R2 = .20). Follow‐up planned t‐tests showed that, compared with non‐clinical participants, patients with SAD were significantly more likely to hold fixed entity beliefs about their own emotions (MSAD = 11.4, SD = 3.54 vs MNC = 7.43, SD = 3.17, t(115) = 6.04, p < .001, d = 1.18). They also held stronger entity beliefs about emotions in general (MSAD = 9.81, SD = 3.44 vs MNC = 8.5, SD = 3.13, t(115) = 2.04, p < .05, d = 0.40) and about their social anxiety (MSAD = 11.73, SD = 4.04 vs MNC = 6.79, SD = 2.78, t(115) = 7.80, p < .001, d = 1.42). This was a small to medium effect on the general scale and a large effect on the personal and anxiety belief scales, according to J. Cohen's (Citation1988) conventions (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Beliefs about emotion in non‐clinical (NC) and social anxiety disorder (SAD) participants.

Note. Patients with SAD held stronger entity beliefs about emotions than non‐clinical participants (in all belief domains), and stronger entity beliefs on the personal and anxiety scales than on the general scales. Non‐clinical participants, by contrast, held weaker entity beliefs on the personal and anxiety scales than on the general. For patients with SAD and non‐clinical participants, there was no significant difference between emotion beliefs on the personal and anxiety scales.

Paired‐samples t‐tests for each group were also used to examine whether participants' personal beliefs about their own emotions differed significantly from their beliefs about emotions in general. We also examined whether their personal beliefs differed from their beliefs about their social anxiety. Patients with SAD endorsed stronger entity beliefs on the personal scale than on the general scale (M(PERSONAL) = 11.4, SD = 3.54 vs M(GENERAL) = 9.81, SD = 3.44, t(74) = −4.71, p < .001, d = 0.54Footnote1), indicating a greater perceived lack of control over their own emotions. They also held stronger entity beliefs about their social anxiety than about emotions in general (M(ANXIETY) = 11.73, SD = 4.04 vs M(GENERAL) = 9.81, SD = 3.44, t(74) = −4.40, p < .001, d = 0.51). There was no significant difference however, between patients' scores on the personal and anxiety belief measures (t(41) = −1.17, p = .25, d = 0.14) (see Fig. 1).

For non‐clinical participants, the reverse pattern emerged. Consistent with previous research (De Castella & Byrne, unpublished data; De Castella et al., Citation2013), non‐clinical participants endorsed entity beliefs less on the personal measure than on the general measure, indicating greater perceived control over their own emotions (M(GENERAL) = 8.5, SD = 3.13 vs M(PERSONAL) = 7.43, SD = 3.17, t(41) = 2.94, p < .01, d = 0.45). They also endorsed entity beliefs less on the anxiety scale than on the general scale (M(GENERAL) = 8.5, SD = 3.13 vs M(ANXIETY) = 6.79, SD = 2.78, t(41) = 3.84, p < .001, d = 0.60), indicating greater perceived control over their social anxiety. Once again, there was no significant difference between non‐clinical participants' scores on the personal and anxiety belief measures (t(41) = 1.83, p = .08).

Hypothesis 2: Emotion beliefs, clinical symptoms, perceived stress, and anxiety in SAD

To examine whether entity beliefs about emotions were associated with higher levels of clinical symptoms, perceived stress, and anxiety in patients with SAD, we first examined Pearson product‐moment correlations between patients' beliefs and their scores on these measures (see Table ). Among patients with SAD, personal and social anxiety emotion beliefs were significantly correlated with perceived stress and trait anxiety. Social anxiety beliefs were also positively correlated with social interaction anxiety. General emotion beliefs, by contrast, were only associated with perceived stress. None of the emotion belief scales were associated with fear and avoidance of social situations as indicated on the LSAS‐SR.

Next, we tested whether patients' emotion beliefs predicted stress and trait anxiety above and beyond what might already be explained by their existing social anxiety symptoms. Using a series of two‐step hierarchical regressions, we controlled for social anxiety (LSAS‐SR and SIAS) in the first step. Emotion beliefs were then entered in the second step to examine the unique variance explained on each of the dependent variables (see Table ). Results revealed that even when controlling for social anxiety, patients' beliefs about their emotions (general, personal, and anxiety belief measures) accounted for 11–23% of unique variance in stress. For trait anxiety, personal emotion beliefs also contributed 4% of unique variance. The general and anxiety belief scales, however, did not.

Table 3. Results of hierarchical regressions predicting variables from emotion beliefs in patients with SAD (n = 75)

Hypothesis 3: Emotion beliefs and well‐being in SAD

To examine whether entity beliefs about emotions were associated with lower levels of well‐being in patients with SAD, we next examined Pearson product‐moment correlations between emotion beliefs and the well‐being measures. Greater personal entity beliefs about emotions were associated with lower self‐esteem and greater negative affect. The same pattern emerged for patients' beliefs about their social anxiety; however, neither measure was associated with positive affect or life satisfaction. General emotion beliefs, on the other hand, were not correlated with any of the well‐being measures.

To see whether patients' emotion beliefs accounted for unique variance in well‐being, we again conducted a series of hierarchal regressions controlling for social anxiety following the procedures outlined above. Once again, personal and anxiety emotion beliefs (but not general beliefs) accounted for unique variance in well‐being: explaining an additional 11–12% of the variance in self‐esteem; and 5–6% of the variance in negative affect. None of the emotion belief measures, however, were significant predictors of life satisfaction or positive affect. Overall, these findings indicate that even when controlling for symptom severity, patients differ in their beliefs about the controllability of their emotions, and these beliefs uniquely predict patients' levels of stress, trait anxiety, self‐esteem, and negative affect.

Discussion

Cognitive models of SAD have emphasised the role of dysfunctional cognitive content in SAD. To date, however, there has been limited research on patients' beliefs about their ability to change or control their emotions. Our results indicate that these beliefs can help to distinguish patients with SAD from non‐clinical participants and that these beliefs are linked to clinical symptoms, stress, anxiety, and well‐being.

For example, SAD patients who believed they could not change or control their emotions reported higher levels of perceived stress and anxiety, higher levels of negative affect, and lower levels of self‐esteem. Even when controlling for social anxiety severity, patients differed in their beliefs about their emotions, and these beliefs explained unique variance on these measures. Interestingly, entity beliefs were not significantly correlated with positive affect or life satisfaction. These results are inconsistent with observed links between emotion beliefs and indices of well‐being in larger undergraduate samples (De Castella et al., Citation2013; Tamir et al., Citation2007). However, it is possible that for patients with SAD, emotion beliefs have a smaller—or indirect—association with these indices of positive well‐being. The large degree of variance in the LSAS‐SR (see Table ) may have also explained the lack of association between emotion beliefs and this measure of social anxiety.

Our findings regarding the clinical significance of beliefs about emotion control accord well with existing research. Hofmann (Citation2000, Citation2005, Citation2007) suggests that perceived control over emotions may also play an important role in promoting treatment for SAD. Patients with SAD typically struggle with their symptoms for a prolonged period, often waiting more than 9 years before finding appropriate specialist care (Wagner, Silove, Marnane, & Rouen, Citation2006). If patients with SAD more readily hold fixed entity beliefs about their emotions and anxiety—believing them to be stable qualities or personality traits rather than a treatable psychiatric disorder—this may help explain why many sufferers fail to seek treatment (Grant et al., Citation2005).

Acknowledging discrepancies between people's broader beliefs and their beliefs about themselves is also important in the context of clinical interventions. Treatment credibility and positive expectations for change in treatment are considered one of the most potent nonspecific factors in predicting general treatment response (Arnkoff, Glass, & Shapiro, Citation2002). Such expectations are linked treatment outcomes for patients with SAD (Safren, Heimberg, & Juster, Citation1997), and they predict rate of change in CBT for SAD patients (Price & Anderson, Citation2011).

These findings have led to renewed interest in the effects of motivational enhancement therapy (Miller, Zweben, DiClemente, & Rychtarik, Citation1992) and motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2002). Research indicates that these approaches are an effective adjunct to CBT for generalised anxiety (Westra, Arkowitz, & Dozois, Citation2009), and there is some support for their efficacy among patients with SAD (Buckner & Schmidt, Citation2009). Motivational enhancement strategies adopt a client‐centred approach to counselling with the aim of helping clients overcome their ambivalence or lack of resolve for change. They can also be flexibly added to existing treatments to improve their effectiveness (Brozovich & Heimberg, Citation2011). However, neither approach explicitly addresses patients' beliefs about their emotions or the effectiveness of treatment in teaching skills for controlling or changing their anxiety. If treatment ambivalence is due in part to patients' entity beliefs about their emotions, strategies for explicitly targeting these beliefs may prove beneficial.

Although the current study makes important contributions to research on emotion beliefs and SAD, several limitations should be noted. First, we developed instruments to assess emotion beliefs at different levels of specificity. We also included indicators of perceived stress, trait‐anxiety, and well‐being, rather than focusing exclusively on clinical symptoms and negative functioning. Nonetheless, as with much of the research on implicit theories (Dweck, Citation1999), the data collected in the current study are based on participant self‐reports. It will therefore be important to build on this work using other measures to further supplement our assessment of emotion beliefs, stress, anxiety, and well‐being. Future research might benefit from including independent evaluations, implicit association tasks, psychophysiological assessments, and behavioural measures. This would also help control for potential self‐report bias and provide information on shared method variance.

A second limitation relates to generalizability. Patients in the current study were carefully screened and only eligible if they met the criteria for a principal diagnosis of generalised SAD. Although this carefully defined clinical population is a key strength of the current study, it is also a limitation. SAD is highly prevalent and is frequently co‐morbid with other mood and anxiety disorders (Schneier, Johnson, Hornig, Liebowitz, & Weissman, Citation1992). Our findings then, while representative of most patients with SAD, cannot be generalised to all people with social anxiety. It is also important to note that in clinical studies, patients are typically seeking treatment for their symptoms and are often required to undergo multiple assessments as part of the overall research programme. In this way, clinical samples such as ours typically reflect a highly motivated population who likely believe in the utility of therapy and their capacity to change. Given that many patients fail to seek treatment (especially patients with SAD), it is possible—and even likely—that entity beliefs about emotions are even more prevalent among non‐treatment‐seekers in the general population. It will also be important to examine whether links between emotion beliefs, clinical symptoms, and well‐being can be generalised across multiple mood and anxiety disorders or alternatively, whether these findings are unique to patients with SAD. Examining patients' beliefs about emotions in other clinical populations will help clarify the role these beliefs play more broadly in emotion dysregulation and psychological illness.

Third, although the current study documents robust cross‐sectional associations between emotion beliefs, perceived stress, anxiety, and well‐being, we still know little about the origins and developmental course of emotion beliefs—such as the potential role that parental messages and parenting practices may play in this process (see for example Monti, Rudolph & Abaied, Citation2013; Rudolph & Zimmer‐Gembeck, Citation2013, this issue). More research is also needed to better understand the causal links between emotion beliefs, perceived stress, anxiety and well‐being, and the implications these beliefs might have for psychosocial interventions and long‐term recovery. We have suggested that beliefs about emotions may play an important role in promoting help seeking, and recovery—particularly in therapeutic approaches such as CBTs which actively teach patients strategies for changing and controlling their emotions. Causal links between implicit beliefs and such outcomes are also consistent with a large body of research on implicit theories (see Dweck, Citation1999 for a review) and emotion regulation (De Castella et al., Citation2013; Tamir et al., Citation2007). Nonetheless, it is also possible that entity beliefs reflect existing deficiencies in emotion regulation or that alternative variables account for the relationship between beliefs and symptoms. Although we controlled for the severity of social anxiety in our analyses and found that emotion beliefs still predicted unique variance in outcomes, it will be important that future work in this area further examines if and how patients' beliefs about their emotions can be changed and what effect (if any) this has on their clinical symptoms, response to treatment, and quality of life.

Notes

The authors of this manuscript do not have any direct or indirect conflicts of interest, financial, or personal relationships or affiliations to disclose.

1. Within‐subjects estimates of effect size using J. Cohen's d have been corrected for dependence between the means (see equation 8, Morris & DeShon, Citation2002).

References

- American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM‐IV) (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM‐V) (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Arnkoff, D. B., Glass, C. R., & Shapiro, D. A. (2002). Expectations and preferences. In J. C. Norcross (Ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work (pp. 335–356). Oxford: University Press.

- Barlow, D. H. (2000). Unraveling the mysteries of anxiety and its disorders from the perspective of emotion theory. The American Psychologist, 55(11), 1247–1263. doi:10.1016/0165‐0327(90)90005‐S

- Beer, J. S. (2002). Implicit self‐theories of shyness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(4), 1009–1024. doi:10.10371/0022‐35l4.83.4.1009

- Boden, M. T., John, O. P., Goldin, P. R., Werner, K., Heimberg, R. G., & Gross, J. J. (2012). The role of maladaptive beliefs in cognitive‐behavioral therapy: Evidence from social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(5), 287–291. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2012.02.007

- Brown, T. A., Dinardo, P., & Barlow, D. H. (1994). Anxiety disorders interview schedule lifetime version (ADIS‐IV‐L) specimen set: Includes clinician manual and one ADIS‐IV‐L client interview schedule. Boulder, CO: Graywind Publications.

- Brozovich, F. A., & Heimberg, R. (2011). A treatment refractory case of social anxiety disorder: Lessons learned from a failed course of cognitive‐behavioral therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 18(3), 316–325. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.07.003

- Bruch, M. A., Fallon, M., & Heimberg, R. G. (2003). Social phobia and difficulties in occupational adjustment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(1), 109–117. doi:10.1037/0022‐0167.50.1.109

- Buckner, J. D., & Schmidt, N. B. (2009). A randomized pilot study of motivation enhancement therapy to increase utilization of cognitive‐behavioral therapy for social anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(8), 710–715. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.04.009

- Clark, D. M. (2001). A cognitive perspective on social phobia. In W. R. Crozier & L. E. Alden (Eds.), International handbook of social anxiety: Concepts, research and interventions relating to the self and shyness. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg , M. R. Liebowitz , D. A. Hope , & F. R. Schneier (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment and treatment (pp. 69–93). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

- Crawford, J. R., & Henry, J. D. (2004). The positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non‐clinical sample. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology / the British Psychological Society, 43(3), 245–265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1348/0144665031752934

- De castella, K., Goldin, P., Jazaieri, H., Ziv, M., Dweck, C. S., & Gross, J. J. (2013). Beliefs about emotion: Links to emotion regulation, well‐being, and psychological distress. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(6), 497–505. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2013.840632

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Dweck, C. S. (1999). Self‐theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Philadelphia: Psychology Press.

- Fresco, D. M., Coles, M. E., Heimberg, R. G., Liebowitz, M. R., Hami, S., Stein, M. B., & Goetz, D. (2001). The Liebowitz social anxiety scale: A comparison of the psychometric properties. Psychological Medicine, 31(6), 1025–1035. doi:10.1017\S003329170105405

- Gaudiano, B. A., & Herbert, J. D. (2003). Preliminary psychometric evaluation of a new self‐efficacy scale and its relationship to treatment outcome in social anxiety disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27(5), 537–555. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026355004548

- Goldin, P. R., Ziv, M., Jazaieri, H., Werner, K., Kraemer, H., Heimberg, R. G., & Gross, J. J. (2012). Cognitive reappraisal self‐efficacy mediates the effects of individual cognitive‐behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(6), 1034–1040. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028555

- Grant, B. F., Hasin, D. S., Blanco, C., Stinson, F. S., Chou, S. P., Goldstein, R. B., & Huang, B. (2005). The epidemiology of social anxiety disorder in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66(11), 1351–1361. doi:https://doi.org/PMID:16420070

- Heimberg, R. G., Brozovich, F. A., & Rapee, R. M. (2010). A cognitive‐behavioral model of social anxiety disorder: Update and extension. Social Anxiety: Clinical, Developmental, and Social Perspectives, 2, 395–422. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978‐0‐12‐375096‐9.00015‐8

- Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., & Mosher, S. W. (2012). The perceived stress scale: Factor structure and relation to depression symptoms in a psychiatric sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 14(3), 247–257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00962631

- Hofmann, S. G. (2000). Treatment of social phobia: Potential mediators and moderators. Clinical Psychology, 7(1), 3–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.7.1.3

- Hofmann, S. G. (2004). Cognitive mediation of treatment change in social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(3), 393–399. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐006X.72.3.393

- Hofmann, S. G. (2005). Perception of control over anxiety mediates the relation between catastrophic thinking and social anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(7), 885–895.

- Hofmann, S. G. (2007). Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: A comprehensive model and its treatment implications. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 36(4), 193–209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070701421313

- Kashdan, T. B., & Herbert, J. D. (2001). Social anxiety disorder in childhood and adolescence: Current status and future directions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 4(1), 37–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009576610507

- Kessler, R., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age‐of‐onset distributions of DSM‐IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

- Kuo, J. R., Goldin, P. R., Werner, K., Heimberg, R. G., & Gross, J. J. (2011). Childhood trauma and current psychological functioning in adults with social anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(4), 463–473. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.11.011

- Ledley, D. R., Erwin, B. A., Morrison, A. S., & Heimberg, R. G. (2013). Social anxiety disorder. In W. E. Craighead , D. J. Miklowitz , & L. W. Craighead (Eds.), Psychopathology: History, theory, and empirical foundations (2nd ed., pp. 147–192). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Leung, A. W., & Heimberg, R. G. (1996). Homework compliance, perceptions of control, and outcome of cognitive‐behavioral. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(5–6), 423–432. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0005‐7967(96)00014‐9

- Liebowitz, M. R. (1987). Social phobia. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry, 22, 141–173.

- Manser, R., Cooper, M., & Trefusis, J. (2011). Beliefs about emotions as a metacognitive construct: Initial development of a self‐report questionnaire measure and preliminary investigation in relation to emotion regulation. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 19(3), 235–246. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.745

- Mattick, R. P., & Clarke, J. C. (1998). Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(4), 455–470. doi:S0005‐7967(97)10031‐6 [pii]

- Mennin, D. S., Mclaughlin, K. A., & Flanagan, T. J. (2009). Emotion regulation deficits in generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and their co‐occurrence. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(7), 866–871. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.04.006

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Miller, W. R., Zweben, A., Diclemente, C. C., & Rychtarik, R. G. (1992). Motivational enhancement therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

- Montesi, J. L., Conner, B. T., Gordon, E. A., Fauber, R. L., Kim, K. H., & Heimberg, R. G. (2012). On the relationship among social anxiety, intimacy, sexual communication, and sexual satisfaction in young couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42(1), 89–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508‐012‐9929‐3

- Monti, J. D., Rudolph, K. D., & Abaied, J. L. (2013). Contributions of maternal emotional functioning to socialization of coping. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31(2), 247–269.

- Morris, S. B., & Deshon, R. P. (2002). Combining effect size estimates in meta‐analysis with repeated measures and independent‐groups designs. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 105–125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1082‐989X.7.1.105

- Moscovitch, D. A., Gavric, D. L., Merrifield, C., Bielak, T., & Moscovitch, M. (2011). Retrieval properties of negative versus positive mental images and autobiographical memories in social anxiety: Outcomes with a new measure. Behavior Research and Therapy, 49(8), 505–517. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.05.009

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 137–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701756946

- Price, M., & Anderson, P. L. (2011). Outcome expectancy as a predictor of treatment response in cognitive behavioral therapy for public speaking fears within social anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 49(2), 1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024734

- Rapee, R. M., Gaston, J. E., & Abbott, M. J. (2009). Testing the efficacy of theoretically derived improvements in the treatment of social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(2), 317–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014800

- Rodebaugh, T. L. (2009). Social phobia and perceived friendship quality. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(7), 872–878. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.05.001

- Rodebaugh, T. L., Woods, C. M., Heimberg, R. G., Liebowitz, M. R., & Schneier, F. R. (2006). The factor structure and screening utility of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale. Psychological Assessment, 18(2), 231–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1040‐3590.18.2.231

- Rodebaugh, T. L., Woods, C. M., & Heimberg, R. G. (2007). The reverse of social anxiety is not always the opposite: The reverse‐scored items of the social interaction anxiety scale do not belong. Behavior Therapy, 38(2), 192–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2006.08.001

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self‐image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Rudolph, J., & Zimmer‐gembeck, M. J. (2013). Parent relationships and adolescents' depression and social anxiety: Indirect associations via emotional sensitivity to rejection threat. Australian Journal of Psychology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12042.

- Safren, S. A., Heimberg, R. G., & Juster, H. R. (1997). Clients' expectancies and their relationship to pretreatment symptomatology and outcome of cognitive‐behavioral group treatment for social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(4), 694. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐006X.65.4.694

- Schneier, F. R., Johnson, J., Hornig, C. D., Liebowitz, M. R., & Weissman, M. M. (1992). Social phobia. Comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiologic sample. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49(4), 282–288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820040034004

- Schneier, F. R., Heckelman, L. R., Garfinkel, R., Campeas, R., Fallon, B. A., Gitow, A., & Liebowitz, M. R. (1994). Functional impairment in social phobia. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 55(8), 322–331. doi:1995‐04074‐001

- Schreiber, F., Bohn, C., Aderka, I. M., Stangier, U., & Steil, R. (2012). Discrepancies between implicit and explicit self‐esteem among adolescents with social anxiety disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 43(4), 1074–1081. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2012.05.003

- Schulz, S. M., Alpers, G. W., & Hofmann, S. G. (2008). Negative self‐focused cognitions mediate the effect of trait social anxiety on state anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(4), 438–449. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.01.008

- Simon, N. M., Otto, M. W., Korbly, N. B., Peters, P. M., Nicolaou, D. C., & Pollack, M. H. (2002). Quality of life in social anxiety disorder compared with panic disorder and the general population. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 53(6), 714–718. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.53.6.714

- Smits, J. A. J., Julian, K., Rosenfield, D., & Powers, M. B. (2012). Threat reappraisal as a mediator of symptom change in cognitive‐behavioral treatment of anxiety disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(4), 624–635. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028957

- Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, P. R., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983). Manual for the state‐trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Tamir, M., & Mauss, I. B. (2011). Social cognitive factors in emotion regulation: Implications for well‐being. In I. Nyklicek , A. Vingerhoets , M. Zeelenberg , & J. Donellet (Eds.), Emotion regulation and well‐being (pp. 31–47). New York: Springer.

- Tamir, M., John, O. P., Srivastava, S., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Implicit theories of emotion: Affective and social outcomes across a major life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 731. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐3514.92.4.731

- Wagner, R., Silove, D., Marnane, C., & Rouen, D. (2006). Delays in referral of patients with social phobia, panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder attending a specialist anxiety clinic. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 20(3), 363–371. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.02.003

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐3514.54.6.1063

- Werner, K. H., Goldin, P. R., Ball, T. M., Heimberg, R. G., & Gross, J. J. (2011). Assessing emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder: The emotion regulation interview. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 33(3), 346–354. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862‐011‐9225‐x

- Westra, H. A., Arkowitz, H., & Dozois, D. J. (2009). Adding a motivational interviewing pretreatment to cognitive behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder a preliminary randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(8), 1106–1117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.014

- Wong, Q. J. J., & Moulds, M. L. (2011). The relationship between the maladaptive self‐beliefs characteristic of social anxiety and avoidance. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 42(2), 171–178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.11.004