Abstract

Objective

Non‐suicidal self‐injury (NSSI) is physically harmful behaviour, primarily used to regulate emotions. Emotion regulatory ability is theorised to develop in the context of primary attachment relationships and to be impacted by the quality of these relationships. We propose a developmental perspective for why some people engage in NSSI.

Method

A questionnaire assessing aspects of attachment, emotion regulation, and NSSI was completed by 237 young adults.

Results

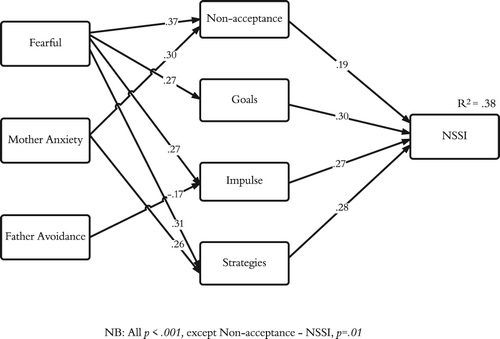

Participants reporting NSSI were more likely to report difficulties in attachment relationships and emotion relation. Using multiple mediation modelling, anxiety related to mothers, and a fearful attachment model predicted NSSI through non‐acceptance of emotional responses and lack of regulatory strategies; the fearful model also predicted NSSI through difficulties in engaging in goal‐directed behaviour and impulse control.

Conclusions

Risk of NSSI may increase as a result of attachment difficulties and associated emotional development; early prevention measures may be useful. Treatment of NSSI should target attachment constructs as well as understanding, expression, and regulation of emotion.

What is already known about this topic

Approximately 13% of young adults report engaging in NSSI, largely to regulate overwhelming negative emotional states.

Individuals who self‐injure report lacking alternative strategies to regulate their emotional states.

Models of NSSI suggest that early familial experiences as well as current emotion regulatory capacity comprise risk factors for NSSI.

What this topic adds

This topic proposes a link between perceptions of early experiences and current emotion regulatory ability as increasing risk of NSSI.

We examine specific pathways from attachment‐related difficulties to NSSI through particular aspects of emotion regulation.

This highlights potential areas for prevention of NSSI through identification of at‐risk individuals as well as options for intervention; this research highlights a role for the development of reflective function in addition to alternative regulatory strategies in treating individuals who self‐injure.

Non‐suicidal self‐injury (NSSI) refers to behaviours that purposefully damage body tissue, for example cutting, burning, or causing blunt trauma to the body, in the absence of suicidal intent (Nock & Favazza, Citation2009). Approximately 13% of young adults report NSSI, with evidence suggesting that university students are even more likely to engage in NSSI (Swannell, Martin, Page, Hasking, & St John, Citation2014; Whitlock et al., Citation2011). Much of the data addressing why people self‐injure, particularly in non‐clinical samples, indicate an emotion regulatory function (e.g., Klonsky, Citation2007, Citation2009). People who self‐injure are prone to frequent, strong negative emotionality, and report limited access to helpful strategies to feel better, often relying on NSSI to change unwanted or unpleasant emotional states (Victor & Klonsky, Citation2014).

Attachment theory posits that an individual's ability to regulate emotion and later interpersonal functioning is shaped by the quality of early primary caregiver–infant relationships, where the carer initially provides an external source of affect regulation (Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist, & Target, Citation2004). During the first 5 months of life, the infants’ ability to understand, label, and regulate emotions develops through the acquisition of reflective functioning or mentalisation, the ability to intuit ones’ own and others internal mental states. This occurs when emotional interactions and caregiver responses accurately reflect the infants’ emotional or mental state, along with comforting expressions (Fonagy & Target, Citation1997). Conversely, when attachment interactions do not adequately reflect emotional states, often due to caregivers’ own difficulty in reflective capacity, the child's ability to identify and interpret their own and others mental states is damaged (Fonagy et al., Citation2004). This article examines the relationship between self‐reported adult attachment, emotion regulation, and NSSI in young adults.

Emotion regulation and NSSI

Affect regulation is the most frequently cited reason for NSSI (Klonsky, Citation2007, Citation2009), and can be achieved using an infinite number of possible methods, which may utilise only the self or may involve others, for example, seeking assistance from a trusted other (Gross, Citation2014). Gross’ process model of emotion regulation and Gratz and Roemer's measure of emotion dysregulation have both been utilised in attempts to explicate differences in emotion regulatory capacity between individuals who do and do not self‐injure (Gratz & Roemer, Citation2004, Citation2008; Gross, Citation1998). Use of Gross’ (Citation1998) model has focused on cognitive reappraisal—where emotional salience of stimuli is reduced or altered to change the meaning of stimuli—and expressive suppression—where outward signs of emotional responses are inhibited. Gross's work indicates that expressive suppression is associated with increased physiological arousal and is less adaptive than cognitive reappraisal, which was more effective in promoting subjective relief from adverse emotional states (Gross, Citation1998; Gross & John, Citation2003). Research using this model has demonstrated that individuals with a history of NSSI report more use of expressive suppression (Hasking, Momeni, Swannell, & Chia, Citation2008) and less use of cognitive reappraisal (Martin, Swannell, Harrison, Hazell, & Taylor, Citation2010) than individuals who do not self‐injure. In contrast, Gratz and Roemer's (Citation2004) work focused on specific areas of dysregulation, including non‐acceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal‐directed behaviour, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies and lack of emotional clarity—all of which, particularly the final two, have been shown to predict NSSI (e.g., Gratz & Roemer, Citation2004, Citation2008).

From attachment to emotion regulation

A sensitive caregiver will interpret and mirror an infant's expressed states along with comforting touch, facial expressions, and vocalisations, enabling the child to form a mental representation of the experienced emotion as well as the caregiver's ability to regulate it (Fonagy et al., Citation2004). This co‐regulation of emotion with the caregiver forms the basis of self‐regulation, along with an understanding of what emotions are and that they can be regulated or changed. Individuals who self‐injure report difficulties labelling emotions (alexithymia; Garisch & Wilson, Citation2015; Lüdtke, In‐Albon, Michel, & Schmid, Citation2016), communicating, and regulating emotions (Gatta, Dal Santo, Rago, Spoto, & Battistella, Citation2016; Klonsky, Citation2007, Citation2009); this may be indicative of incongruous early interactions with caregivers and associated difficulties in reflective functioning (Fonagy et al., Citation2004).

When caregivers fail to respond, misinterpret the infant's affective signals, or exacerbate the infant's arousal through over‐reflection of emotion, the infant is unable to create an accurate representation of the emotion or understand how to regulate it (Fonagy et al., Citation2004). Along with reflective functioning, responses from caregivers lead to the development of different coping strategies within infants; the avoidant infant tends to suppress emotional expression, whereas the resistant infant heightens emotional expression, and the disorganised infant may display either response or freeze in response to perceived threats (Cassidy, Citation1994). Each of these patterns of attachment may increase the risk of NSSI through different emotion regulatory difficulties.

Conceptualising adult attachment

Within attachment theory and research there exists two distinct but related research traditions; one focuses on the developmental and psychodynamic consequences of early attachment, including the development of reflective functioning and regulation of emotion (e.g., Fonagy et al., Citation2004). The other is based on a more personality and social psychology approach, examining interpersonal aspects of attachment, including internal working models of self and other in current adult relational functioning (e.g., Hazan & Shaver, Citation1987). We take a unified, integrative approach, described by Shaver and Mikulincer (Citation2002). We have used insights from developmental theory applied to a young adult population and assess attachment as a general construct of contemporary interpersonal functioning. Shaver and Mikulincer (Citation2002) suggested that each of these traditions, and the measures each utilises, tap into underlying, core relational, and psychodynamic constructs. Adult attachment styles, as well as recall of early received parenting, reflect early attachment experiences in contemporary attachment‐relevant contexts, including current feelings of avoidance or anxiety related to parents, but may differ somewhat in romantic attachments (Bartholomew & Shaver, Citation1998).

We used the Relationship Questionnaire (RQ; Bartholomew & Horowitz, Citation1991), Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI; Parker, Tupling, & Brown, Citation1979), and the parent scales from the Experiences in Close Relationships–Relationship Structures Scale (ECR‐RS; Fraley, Heffernan, Vicary, & Brumbaugh, Citation2011). While each of these measures alone may not fully describe the impact of early attachment experience, together, they may provide a comprehensive assessment of childhood experiences in the parent–child relationship (received care, overprotection, and controlling behaviour), as well as contemporary attachment to parents and others. We then examine which specific aspects of relational functioning are more likely to predict self‐injury, directly and indirectly, to inform theory and practice.

The current study

In the current study, we hypothesised that participants engaging in NSSI would do so primarily for emotion regulation purposes and that reported difficulties in emotion regulation would mediate the relationship between self‐reported attachment and NSSI. The nature of these predicted relationships are explored.

METHOD

Participants

The 237 participants (212 female) were aged between 18 and 25 years (M = 20.77, standard deviation (SD) = 2.21). Participants were recruited from a large Australian university; 82.1% identified as Australian, 7.7% Southeast Asian, and 10.2% as ‘other’. Of the participants, 86.5% were currently completing higher education degrees, while 9.7% had completed a degree, and 3.8% reported completing high school as their highest level of education.

Materials

Inventory of Statements about Self‐injury

The ISAS (Inventory of Statements about Self‐injury; Klonsky & Glenn, Citation2009) was introduced with the statement: ‘Self‐injury is defined as the deliberate destruction of body tissue without intention to die. Please only endorse a behaviour if you have done it intentionally (i.e., on purpose) and without suicidal intent (i.e., not for suicidal reasons).’ Participants then selected either ‘I have engaged in self‐injury’ or ‘I have not engaged in self‐injury’. Participants responding in the affirmative were then asked about the frequency of 12 NSSI behaviours as well as questions regarding onset and duration of the behaviour (Klonsky & Glenn, Citation2009). The ISAS also assesses 13 key functions of NSSI using a series of 39 statements about why people self injure; for example, ‘When I self‐injure, I am …’ Responses include, for example, ‘… calming myself down’, and ‘… creating a boundary between myself and others’. Response options provided are 0 = not relevant, 1 = somewhat relevant, and 2 = very relevant. Functions were assessed individually to ascertain what the primary function of NSSI was in the current sample, and alphas are reported for each: Affect Regulation .71, Interpersonal Boundaries .75, Self‐Punishment .82, Self Care .54, Anti‐Dissociation .84, Anti‐Suicide .88, Sensation Seeking .53, Peer Bonding .75, Interpersonal Influence .66, Toughness .77, Marking Distress .78, Revenge .81, and Autonomy .78. Alphas for the self‐care and sensation seeking subscales were quite low. These were also the least commonly reported functions of NSSI, suggesting that they were less salient to this particular sample. Glenn and Klonsky (Citation2011) found that over a 1‐year period, responses to interpersonal functions were more stable than responses to intrapersonal functions, which may in part explain more variable responding to these particular functions. These subscales were used for descriptive purposes only, to establish the most commonly reported function of NSSI, and are not used in any analytical procedures.

Relationship Questionnaire

The RQ (Relationship Questionnaire; Bartholomew & Horowitz, Citation1991) is an adult attachment measure assessing four self–other relationship models: secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and fearful. These models are based on the four infant attachment styles and reflect these on dimensions of anxiety and avoidance (Bartholomew & Horowitz, Citation1991). The RQ was selected to reflect current thinking about interpersonal functioning. Participants are provided a single statement reflecting each model and asked how much each model or style is like them, with responses recorded on a 7‐point Likert scale. The scale has good discriminant validity (Bartholomew & Horowitz, Citation1991).

Parental Bonding Instrument

The PBI (Parental Bonding Instrument; Parker et al., Citation1979) requests participants to recall interactions with each parent prior to age 16 and to indicate on a 4‐point Likert scale how much each parent was like each of 25 statements, from 1 (very unlike) to 4 (very like). The PBI assesses care and control from both parents. ‘Optimal parenting’ is denoted by high care and low control scores. Examples of statements from the PBI include ‘spoke to me in a warm and friendly voice’ (care) and ‘Tried to control everything I did’ (control). Care and control scores are calculated for each parent. Longitudinal work has demonstrated that optimal parenting classified by the PBI predicted identification with a secure model of attachment using the RQ, whereas affectionless control predicted identification with a preoccupied model of attachment in women 30 years later (Wilhelm, Gillis, & Parker, Citation2016). The PBI has good test–retest reliability and good construct and convergent reliability (Parker et al., 1979,). Cronbach's alphas in the current sample were: mother care, .93; control, .91 and father care, .94; control, .90.

Experiences in Close Relationships–Relationship Structures Questionnaire

The ECR‐RS (Fraley et al., Citation2011) consists of 36 items assessing four relationship domains (mother, father, friend, and romantic partners; Fraley et al., Citation2011). Response options were given on a 7‐point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) and summed to provide scores on two subscales: anxiety and avoidance for each relationship (i.e., how much or little they would rely on this person, or use them as a safe haven or secure base; Fraley et al., Citation2011). The ECR‐RS shows good test–retest reliability and internal validity (Fraley et al., Citation2011). Only responses on the mother and father scales are reported here. Cronbach's alphas in the current sample were: mother anxiety, .87; avoidance, .54 and father anxiety, .89; avoidance, .75.

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

The ERQ (Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; Gross & John, Citation2003) comprises six items measuring cognitive reappraisal strategies (e.g., ‘When I'm faced with a stressful situation, I make myself think about it in a way that helps me stay calm’) and four measuring expressive suppression (e.g., ‘I control my emotions by not expressing them’). Items are assessed on a 7‐point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The ERQ shows high test–retest reliability and acceptable convergent and discriminant validity, with alpha coefficients averaging .79 for reappraisal and .73 for suppression (Gross & John, Citation2003). In the current sample, alphas were .89 for reappraisal and .82 for suppression.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale

The DERS (Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; Gratz & Roemer, Citation2004) comprises 36 items, with six subscales: non‐acceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal‐directed behaviour, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. Sample items include ‘I have difficulty making sense out of my feelings’ and ‘When I'm upset, I know that I can find a way to eventually feel better’ (reverse scored). Responses are scored on a 5‐point Likert Scale from 1 (almost never—0–10%) to 5 (almost always—91–100%). The scale has good test–retest reliability, good construct, and predictive validity, with Cronbach's alpha of .93 for the total scale (Gratz & Roemer, Citation2004). In the current sample, alphas for each subscale were: non‐acceptance of emotional responses, .93; difficulties engaging in goal‐directed behaviour, .90; impulse control difficulties, .84; lack of emotional awareness, .84; limited access to emotion regulation strategies, .93; and lack of emotional clarity, .89.

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained from the host institution. Participation was online, in participants’ own time, using a URL included on recruitment materials, which included posters, flyers, Facebook, and a weekly email to students outlining current research studies. Recruitment materials advised that the study aimed to examine emotion regulation and coping strategies and included NSSI as an area of interest. Links to online and telephone help services were included on the questionnaire webpage. Information about the study, the type of questions to be asked, anonymity of responses, and freedom to withdraw was provided at the start of the questionnaire. Consent was implied through completion of the questionnaire.

Data analysis

Preliminary analyses examined group differences on each of the selected measures. Logistic regressions (controlling gender and age) were then conducted using SPSS v.20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to ascertain which subscales of the attachment and emotion regulation measures best predicted NSSI. Mplus v.6 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2011, Los Angeles, CA, USA) was used to conduct multiple mediation tests using 5,000 bootstrapped re‐samples. Relationships were modelled between specific aspects of parental attachment, emotion regulation subscales, and NSSI. As NSSI is a dichotomous variable, in these analyses, coefficients were calculated using robust weighted least squares estimation (WLSMV; Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2011). Bias‐corrected 95% confidence intervals are reported to estimate the size of all indirect effects.

RESULTS

Preliminary analyses

Of the 237 participants, 38.4% (N = 91) stated that they had engaged in self‐injury. Females were more likely to self‐injure than males, χ 2(2) = 4.90, p = .03, ϕ = −.153. Mean age of onset of NSSI was 13.81-years (SD = 3.96) with NSSI behaviour lasting an average of 5.8-years (SD = 4.45). The most common method of self‐injury was cutting—78% of self‐injurers endorsed this (number of times: M = 92.6, SD = 260.39); 60.4% reported severe scratching (M = 37.6, SD = 119.44), 59.3% banging or hitting the body (M = 49.0, SD = 112.75), 42.9% pinching (M = 66.2, SD = 16.26), 42.8% biting (M = 26.4, SD = 53.78), 33% skin carving (M = 5.7, SD = 53.78), and 26% endorsed burning (M = 8.1, SD = 34.44). Analyses of responses on the ISAS demonstrated that 94.8% of self‐injuring participants indicated that a primary purpose of their self‐injury was affect regulation.

Participants reporting NSSI were more likely to identify difficulties with attachment relationships, especially with mothers, and more difficulty regulating emotions (Table ). Bivariate correlations between attachment variables indicated that identification with a secure model of attachment was associated with viewing mothers and fathers as caring, reporting less anxiety related to mothers and fathers, and avoidance of fathers. Scores on the dismissing model were associated with viewing mothers as less caring and more controlling. Preoccupation was only mildly correlated with less avoidance related to fathers. Identifying with a fearful model of attachment was correlated with viewing both parents as less caring, reporting more anxiety related to relationships with both parents, and less avoidance related to fathers. Correlations also indicated that attachment variables were correlated as expected with emotion dysregulation variables (Table ).

Table 1. Comparisons of means ( SD ) on variables of interest by group (df all 1,162)

Table 2. Bivariate correlations on variables of interest

Multiple mediation

Variables that significantly predicted NSSI in regression analyses were used for the model (see Table ). All non‐significant paths were removed, and the final model (Fig. 1) explained 38% of variance in reporting NSSI. Indirect effects were also observed; specifically, attachment‐related anxiety with mothers indirectly predicted NSSI through limited access to emotion regulation strategies. A fearful attachment style indirectly predicted NSSI through each of the following: difficulties engaging in goal‐directed behaviour, impulse control difficulties, and limited access to emotion regulation strategies (Table ).

Table 3. Regressions predicting NSSI, controlling for age and gender

Table 4. Significant indirect effects from attachment variables to NSSI, working through emotion dysregulation variables

DISCUSSION

We assessed whether perceived difficulties in early parenting and contemporary thinking about attachment relationships were indirectly related to NSSI, working through emotion regulation difficulties. Correlations between the different aspects of attachment were as expected from both the developmental and social traditions of attachment research. In particular, identifying with a secure model was associated with more positive and caring relationships with both parents, whereas identification with a fearful model was associated with more anxiety related to parents perceived as less caring. Participants who self‐injured differed from those who did not in reporting more anxiety related to attachment relationships, particularly with mothers who were perceived as less caring, and identified more with a fearful model of attachment. They also reported more difficulty regulating emotions compared to participants who had never self‐injured and identified affect regulation as the primary purpose of NSSI. Multiple mediation analyses revealed a fearful adult attachment model, anxiety related to attachment to mothers, and avoidant attachment to fathers predicted NSSI, with differential relationships between attachment variables and specific emotion regulation strategies.

Of note, anxiety around current relationships with mothers and a fearful model of attachment were associated with reporting an inability to accept negative emotional states and generate strategies to cope with them for participants who self‐injured. This suggests that these individuals may have been unable to adequately internalise emotional labelling and regulation in early childhood, creating difficulties in accepting and regulating these in later life (as indicated by Fonagy et al., Citation2004). A fearful model additionally predicted difficulties in goal‐directed behaviour and increased impulsive behaviour; each of these in turn predicted NSSI. Identification with the fearful model is indicative of a sense of unworthiness and that others are untrustworthy, unable, or unwilling to offer love and support (Bartholomew & Horowitz, Citation1991). In this sample, this may be interpreted as increasing likelihood of NSSI as a strategy to reduce negative emotional states, reflecting doubt in one's own ability to regulate emotions in a more productive way and difficulty using others for support. While long‐term developmental data are required to conclusively support this pathway, this does indicate mentalisation treatment (used with success in the treatment of borderline personality disorder) for young adults who self‐injure, focusing on improving individuals’ understanding of their own and others mental states, with a view to improve affect regulatory ability (Fonagy et al., Citation2014). This may also indicate utility for relationship‐based treatment, encouraging flexible use of external support for assistance when appropriate.

Father avoidance was negatively associated with impulse control difficulties. Children with an avoidant attachment are more controlled in their behaviour, tending not to display distress and anger as these emotions were often met with rejection, rather than comfort, from primary caregivers (Cassidy, Citation1994). Avoidance of fathers appears protective in this sample in terms of controlling impulsive behaviour, possibly supporting greater importance of maternal relationships in the use of NSSI. This sample was largely female, and as a result, these findings may be applicable specifically to mother–daughter and father–daughter relationships. The maternal role, particularly with daughters, has been conceptualised as being more important in terms of reciprocal helping and caring than father–daughter relationships (Boyd, Citation1989); this may point to an important role of perceived care and support in female maternal attachment and NSSI. Future prospective work could usefully examine the specific differences between attachment relationships with mothers and fathers for both males and females to establish clear pathways, elucidating the potential impact of these on emotion regulation and propensity to self‐injure.

Limitations

The present study is not without limitations. The sample was self‐selected and unbalanced in terms of gender, so it may be that our results reflect the responses and actions of young women rather than the general population. In addition, the study utilised a cross‐sectional, self‐report design; the findings indicate that this model should be tested using a longitudinal design. Use of the current measures along with discourse analysis and use of the Adult Attachment Interview (George, Kaplan, & Main, Citation1985) or the newly developed Reflective Functioning Scale (Fonagy et al., Citation2016) would add further validity to the approach taken here, as well as the findings presented.

Cronbach's alphas for mother avoidance and two ISAS functions (self‐care and sensation‐seeking) were quite low for this sample. Examination of the individual items on the mother avoidance scale indicated that responses to the item ‘I don't feel comfortable opening up to my mother’ reduced the scale reliability in this sample; if deleted, Cronbach's alpha for the scale increased to .73. This item was retained to maintain consistency and allow comparability across studies.

Implications

Our findings, along with theory, suggest that risk of NSSI may develop from a very early age, during the primary attachment relationship. If supported by further longitudinal work, prevention efforts may benefit from aiming to promote healthy attachment relationships in order to provide optimal conditions for the development of effective emotion regulation. Targeted interventions for young adults who self‐injure could include support for developing organised reciprocal relationships and understanding of relational dynamics, as well as targeting emotional understanding, expression, and regulation. Both mentalisation treatment (Fonagy et al., Citation2014) and emotional acceptance‐based training (Gratz & Gunderson, Citation2006) are supported for use in those with borderline personality disorder and are indicated here.

REFERENCES

- Bartholomew, K. , & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four‐category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226–244.

- Bartholomew, K. , & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Methods of assessing adult attachment. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 25–45). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Boyd, C. J. (1989). Mothers and daughters: A discussion of theory and research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51, 291–301.

- Cassidy, J. (1994). Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2–3), 228–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540‐5834.1994.tb01287

- Fonagy, P. , Gergely, G. , Jurist, E. L. , & Target, M. (2004). Affect regulation, mentalization and the development of the self. London, UK: Karnac Books.

- Fonagy, P. , Luyten, P. , Moulton‐perkins, A. , Lee, Y. W. , Warren, F. , Howard, S. , … Lowyck, B. (2016). Development and validation of a self‐report measure of mentalizing: The Reflective Functioning Questionnaire. PLoS One, 11(7), e0158678. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158678

- Fonagy, P. , Rossouw, T. , Sharp, C. , Bateman, A. , Allison, L. , & Farrar, C. (2014). Mentalization‐based treatment for adolescents with borderline traits. In C. Sharp & J. L. Tackett (Eds.), Handbook of borderline personality disorder in children and adolescents (pp. 313–332). New York, NY: Springer.

- Fonagy, P. , & Target, M. (1997). Attachment and reflective function: Their role in self‐organization. Development and Psychopathology, 9(04), 679–700.

- Fraley, R. C. , Heffernan, M. E. , Vicary, A. M. , & Brumbaugh, C. C. (2011). The experiences in close relationships‐relationship structures questionnaire: A method for assessing attachment orientations across relationships. Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 615–625. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022898

- Garisch, J. A. , & Wilson, M. S. (2015). Prevalence, correlates, and prospective predictors of non‐suicidal self‐injury among New Zealand adolescents: Cross‐sectional and longitudinal survey data. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9(1), 28–39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034‐015‐0055‐6.

- Gatta, M. , Dal santo, F. , Rago, A. , Spoto, A. , & Battistella, P. A. (2016). Alexithymia, impulsiveness, and psychopathology in nonsuicidal self‐injured adolescents. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 12, 2307–2317. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S106433.

- George, C. , Kaplan, N. , & Main, M. (1985). The adult attachment interview (Unpublished protocol). Department of Psychology, University of California, Berkeley, CA.

- Glenn, C. R. , & Klonsky, E. D. (2011). Prospective prediction of nonsuicidal self‐injury: A 1‐year longitudinal study in young adults. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 751–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.04.005

- Gratz, K. L. , & Gunderson, J. G. (2006). Preliminary data on an acceptance‐based emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate self‐harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy, 37(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2005.03.002

- Gratz, K. L. , & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/0882‐2689/04/0300‐0041/0

- Gratz, K. L. , & Roemer, L. (2008). The relationship between emotion dysregulation and deliberate self‐harm among female undergraduate students at an urban commuter university. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 37(1), 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070701819524

- Gross, J. J. (1998). Antecedent‐ and response‐focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐3514.74.1.224

- Gross, J. J. (2014). Emotion regulation: Conceptual and empirical foundations. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (2nd ed., pp. 3–20). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Gross, J. J. , & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022‐3514.85.2.348

- Hasking, P. , Momeni, R. , Swannell, S. , & Chia, S. (2008). The nature and extent of non‐suicidal self‐injury in a non‐clinical sample of young adults. Archives of Suicide Research, 12, 208–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811110802100957

- Hazan, C. , & Shaver, P. R. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511–524.

- Klonsky, E. D. (2007). The functions of deliberate self‐injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002

- Klonsky, E. D. (2009). The functions of self‐injury in young adults who cut themselves: Clarifying the evidence for affect‐regulation. Psychiatry Research, 166, 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.02.008

- Klonsky, E. D. , & Glenn, C. R. (2009). Assessing the functions of non‐suicidal self‐injury: Psychometric properties of the Inventory of Statements about Self‐injury (ISAS). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31(3), 215–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862‐008‐9107‐z

- Lüdtke, J. , In‐albon, T. , Michel, C. , & Schmid, M. (2016). Predictors for DSM‐5 nonsuicidal self‐injury in female adolescent inpatients: The role of childhood maltreatment, alexithymia, and dissociation. Psychiatry Research, 239, 346–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.026.

- Martin, G. , Swannell, S. , Harrison, J. , Hazell, P. , & Taylor, A. (2010). The Australian National Epidemiological Study of Self‐Injury (ANESSI). Brisbane, Australia: Centre for Suicide Prevention Studies.

- Muthén, L. K. , & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2011). Mplus user's guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Nock, M. K. , & Favazza, A. R. (2009). Non‐suicidal self‐injury: Definition and classification. In M. K. Nock (Ed.), Understanding nonsuicidal self‐injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment (pp. 9–18). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Parker, G. , Tupling, H. , & Brown, L. B. (1979). A parental bonding instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 52(1), 1–10.

- Shaver, P. R. , & Mikulincer, M. (2002). Attachment‐related psychodynamics. Attachment & Human Development, 4(2), 133–161.

- Swannell, S. V. , Martin, G. E. , Page, A. , Hasking, P. , & St john, N. J. (2014). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self‐injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta‐analysis and meta‐regression. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behaviour, 44, 273–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12070

- Victor, S. E. , & Klonsky, E. D. (2014). Daily emotion in non‐suicidal self‐injury. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70, 364–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22037

- Whitlock, J. , Muehlenkamp, J. , Purington, A. , Eckenrode, J. , Barreira, P. , Baral abrams, G. , … Knox, K. (2011). Nonsuicidal self‐injury in a college population: General trends and sex differences. Journal of American College Health, 59(8), 691–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2010.529626

- Wilhelm, K. , Gillis, I. , & Parker, G. (2016). Parental bonding and adult attachment style: The relationship between four category models. International Journal of Womens Health and Wellness, 2(1), 1–7.