Abstract

Objective

Sporting contexts have been found to be both a protective and risk factor in terms of externalising behaviours in adolescence. The current study sought to explain the inconsistent findings by examining the attributes of peers in sporting environments. Specifically, the prosocial and risky attributes of sporting co‐participants were examined as moderators to the relationship between the intensity of sports participation in adolescence and externalising behaviours.

Method

Australian adolescents (N = 1,816) were sampled from an economically and geographically diverse range of high schools in Years 9 and 11 (female = 54.7%, Mage = 15.1). The 1,405 sport participants reported on the frequency they engaged in externalising behaviours including minor delinquency and school‐conduct issues. They also reported the proportion of friends in their sport who engaged in prosocial and risky behaviours.

Results

The positive association between sports participation intensity and externalising behaviours was moderated by both prosocial and risky peers. More time spent in sport was associated with higher levels of externalising behaviours when the sport exposed the participants to more peers who engaged in risky behaviours and fewer peers who engaged in prosocial behaviours. In contrast, there was no significant association between sports participation intensity and externalising behaviours when the sporting environment included moderate or lower levels of risky peers, irrespective of the level of prosocial peers.

Conclusions

This research highlights the need to consider the attributes of co‐participants in structured activities when predicting risks or benefits.

What is already known about this topic

Sports participation has been linked in some studies to externalising behaviours in adolescence.

Peer processes are known to play a role in externalising behaviours, with adolescents reporting more externalising behaviours when they perceive it to be normative within their friendship group.

Within a sporting context, there is some evidence adolescents report more externalising behaviours when the sporting context exposes them to risky co‐participants.

What this topic adds

The current study adds to the field by acknowledging that sporting contexts are variable environments, exposing adolescents to a range of peers with different attributes.

The current study advances previous literature by exploring the protective role of prosocial peers in sporting contexts.

The findings indicate that it is not simply the presence of risky peers in sporting environments that predict externalising behaviours, it is the combination of high levels of risky peers and low levels of prosocial peers.

A considerable body of research has focused on developmental outcomes associated with participating in sporting activities. Participating in sport during adolescence is associated with higher self‐esteem, lower rates of school drop‐out, higher academic performance, and lower levels of peer rejection (Barber, Stone, & Eccles, Citation2010; Fredricks & Eccles, Citation2006; Shulruf, Citation2010). However, sports participation is also linked to some negative developmental indicators including underage alcohol use and abuse (Lisha, Crano, & Delucchi, Citation2014; Modecki, Barber, & Eccles, Citation2014). There is also evidence for sport participants engaging in a range of externalising behaviours though the evidence is mixed. Externalising behaviours are linked to a lack of inhibitory control that results in antisocial, defiant, and aggressive behaviours (Hinshaw, Citation1992). The current study operationalises externalising behaviours broadly to include school‐related conduct problems, minor delinquency, and aggressive behaviours (e.g., Vernon, Modecki, & Barber, Citation2018).

Kelley and Sokol‐Katz (Citation2011) found that rates of externalising behaviours were higher for sport participants engaging in more sports compared to sport participants engaging in fewer sports. Furthermore, boys with higher levels of sporting activity reported more externalising behaviours than boys with lower levels of sporting activity (Begg, Langley, Moffit, & Marshall, Citation1996). In contrast, Fredricks and Eccles (Citation2005) found no association between sports participation and externalising behaviours and in a subsequent study found sport participants reported lower levels of externalising behaviours (Fredricks & Eccles, Citation2006). Perhaps the reason behind these contrasting results relate to the diverse attributes of sporting contexts examined, and high variability in risk‐taking behaviours among sport participants. Given the key role of peers in risk taking, the peer group composition of sport contexts should be considered when examining the relationship between sports participation and externalising behaviours.

Adolescents engaging in sport are in regular contact with others who also participate in the activity. These co‐participants are often like‐minded peers who share their interests, resulting in new found friendships, shared experiences, and teamwork (Barber et al., Citation2010; Fredricks & Simpkins, Citation2013). Therefore, the role of sports participation in exposure to risky or protective cultures should be considered as a potential context where the peer group might either promote or discourage externalising behaviours. One mechanism proposed to explain the influence of peers on externalising behaviours is the normalisation of these behaviours in a peer network. Frequently occurring behaviours in a peer network may come to be perceived as normative (Granovetter, Citation1985). Normalised behaviours in a peer network would be expected to direct the behaviours of individual adolescents when there is perceived social pressure to conform. Haynie (Citation2002) investigated this proposition by measuring the proportion of friends within a peer network that engaged in externalising behaviours, and of those who did not. Results indicated belonging to a peer group with more delinquent peers and fewer non‐delinquent peers increased the likelihood of engaging in externalising behaviours. These dynamics may be particularly important in peer contexts characterised by shared culture and emphasis on working together on common goals, such as sports.

The relationship between sports participation and externalising behaviour can be at least partially explained by the extent to which co‐participants in the sporting context engage in the externalised behaviours (Blomfield & Barber, Citation2010). Co‐participants who engage in externalising behaviours can be considered risky peers, as their behaviours place members of their peer network at risk of engaging in the same externalising behaviours. This link has been demonstrated for both alcohol use and truancy (Blomfield & Barber, Citation2010). To extend these findings, it is important to consider the amount of exposure when probing the role of sport‐based peers. Research and theory has demonstrated that exposure to any developmental context, such as a sporting environment, needs to occur for an extended period of time for the context to have an impact on developmental outcomes (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1995). Thus, this study considers whether intensity of participation exacerbates susceptibility to peer influence.

While the role of co‐participants' externalising behaviours has been examined in relation to sport participants' engagement in externalising behaviours, less is understood about the role of co‐participants' prosocial behaviours. Co‐participants who engage in positive behaviours and have positive tendencies can be considered prosocial peers. Prosocial peers often engage in behaviours related to high achievement at school, offer encouragement for constructive activities, are involved in the community, and have goal orientated behaviours (Simpkins, Eccles, & Becnel, Citation2008). When examining peer attributes in sport, Fredricks and Eccles (Citation2005) found prosocial peers mediated the relationship between sports participation and different developmental outcomes such as higher school engagement and lower depressed mood. However, no research has examined if prosocial peers can reduce the likelihood of sport participants engaging in externalising behaviours. As such, further research into the role of co‐participants' prosocial behaviours in predicting less externalised behaviour is needed.

In order to further understand the conditions under which adolescent sports participation predicts externalising behaviours, the current study examined the role of both prosocial and risky peers in sport. Previous research has found that peer networks in general comprise both protective and risk attributes (Haynie, Citation2002). Similarly, sporting environments expose adolescents to a diverse range of peers (Barber et al., Citation2010) with a likelihood of both risky and prosocial participants in a single sporting context. By examining the interaction between the prosocial and risky attributes of co‐participants in sport, we acknowledge that there is diversity among sporting environments. We explore whether participation intensity plays a role in the connection between exposure to prosocial or risky co‐participants and externalising behaviour prevalence.

In the current study, gender and year level were controlled, as boys (Overbeek & Andershed, Citation2011) and older adolescents (Flannery, Rowe, & Gulley, Citation1993) report engaging in more externalising behaviours compared to girls and younger adolescents respectively. To align with the study’s aims, several hypotheses were devised. First, it was hypothesised that more hours spent participating in sports would predict more externalising behaviour. Second, it was hypothesised that the association between sporting intensity and externalising behaviours for adolescent sports participants would be conditional on characteristics of the peers involved in the sport. Specifically, the strength of the positive relationship between hours spent participating in sport and externalising behaviour would be moderated by peer characteristics. Consistent with previous research on social groups (Haynie, Citation2002), it was expected that having less exposure to prosocial peers, in conjunction with more exposure to risky peers in one’s sport was expected to produce a significant and positive relationship between sports participation and externalising behaviours. When fewer risky peers are present in the sport, the presence of prosocial peers was not expected to be a significant determinant of the link between target sport intensity and externalising behaviours.

METHOD

Participants

The current study used data from the second wave of the Youth Activity Participation Study (YAPS) conducted in Western Australia. Participants included 1,816 (54.7% girls, 45.3% boys) students from Grades 9 (N = 1,154) and 11 (N = 662) sampled from 34 schools. Participant age ranged from 13 to 18 (M = 15.05, SD = 1.04). The sample was mostly Caucasian (81.8%) with Asian (6.9%), Aboriginal (1.5%), and other ethnicities (9.8%) also responding.

Materials

Externalising behaviours

Adolescent externalising behaviours were assessed with nine items (α = .79) adapted from Fredricks and Eccles (Citation2005). Participants were asked how often in the previous 6 months participants had been involved in behaviours such as truancy, damaging public property, dangerous behaviour, physical fights, and trouble with police. The responses were coded on an 8‐point scale (1 = none, 2 = once, 3 = 2–3 times, 4 = 4–6 times, 5 = 7–10 times, 6 = 11–20 times, 7 = 21–30 times, 8 = 31 or more times), and a mean score was calculated.

Target sport intensity

Participants were asked to first specify if they played sport either at school or in the community, what sports, and the number of hours they engaged in each sport. To assist this process, participants were provided with a check list of common sports in addition to being informed that physical education classes in school and dance did not count as sport. Second, participants who self‐selected themselves as a sports participant were asked to identify in which sport they spent the most time to be designated as their target sport. Of the 1,816 participants, 1,405 (77.4%) specified a target sport. Consistent with previously published studies, intensity is considered to be the amount of time spent in a particular activity (Abbott & Barber, Citation2011; Drane & Barber, Citation2016; Gardner, Roth, & Brooks‐Gunn, Citation2008). Thus, target sport intensity is the number of hours participants reported spending in the sport in which they spent the most time.

Prosocial and risky peers

After identifying the sport in which participants spent the most time, they were asked questions pertaining to the characteristics of their friends in that sport. Prosocial peers was measured using the mean from a three‐item scale (α = .68). The three items asked participants what proportion of their friends in the sport were planning to go to university, doing very well in school, and encouraged you to do their best in school. Risky peers was also measured using a three‐item scale (α = .71) comprised of items asking what proportion of friends in the sport regularly drank alcohol, regularly used illegal drugs, and were likely to skip school. The items used to measure prosocial and risky peers were taken from longer scales commonly used in the field (Eccles & Barber, Citation1999; Fredricks & Eccles, Citation2005). All responses were measured on a 5‐point scale (1 = none to 5 = all).

Procedure

Surveys were administered in schools following written consent from the school principal, parents, and students. Participants completed the survey during school time, on laptops provided by the research team, or on a paper survey if preferred by the school, in a setting where teachers and school personnel could not see their responses. Ethical approval was granted by the University’s Human Research Ethics Committee, the Department of Education, and the Catholic Education Office.

Analytic strategy

After examining descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations, the hypotheses were tested in a three‐step hierarchical regression analysis. At the first step of the analysis, externalising behaviours was regressed on sporting intensity, prosocial peers, and risky peers. Gender and year level were also entered as control variables. At the second step of the analysis, three separate two‐way mean‐centred interaction terms were added to the regression analysis. These interaction terms comprised all possible pairings of sport intensity, prosocial peers, and risky peers. Finally, at the third step of the analysis a three‐way mean‐centred interaction term was added to the regression analysis.

A variant of the pick‐a‐point technique was employed to investigate the significant three‐way interaction (Hayes, Citation2013). High and low values of target sport intensity, prosocial peers, and risky peers were one standard deviation above and below the mean (or the minimum if the standard deviation was greater than the mean) and moderate values were the mean. In the analysis, the statistical significance of the sporting intensity and prosocial peers interaction term was calculated at low, moderate, and high levels of the third variable in the interaction, risky peers. This analysis determines if the moderation between sporting intensity and prosocial peers is moderated by the level of prosocial peers, thereby completing a moderated moderation analysis (Hayes, Citation2013). Finally, the sporting intensity and prosocial peers interaction term at low, moderate, and high levels of risky peers were examined via simple slopes. This process resulted in three individual simple slopes analysis. Specifically, the relationship between sporting intensity and externalising behaviours at differing levels of prosocial peers was examined via simple slopes at (1) high levels of risky peers, (2) moderate levels of risky peers, and (3) low levels of risky peers. The hypotheses were evaluated based upon the direction and statistical significance of the relationships at the final step of the regression analysis and the simple slopes analyses.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables are in Table . More frequent externalising behaviours were significantly associated with more hours participating in the target sport, lower levels of prosocial peers, and higher levels of risky peers. Males reported significantly higher levels of externalising behaviours, more hours of participation in their target sport, and lower levels of prosocial peers in comparison to females. Additionally, Year 11 students reported significantly more frequent externalising behaviours, greater target sport intensity, more risky peers, and fewer prosocial peers in comparison to Year 9 students.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations between externalising behaviours, sporting intensity, prosocial peers, risky peers, gender, and year level for the participants engaging in sports (N = 1,194)

Moderated regression

A moderated regression analysis was conducted using Hayes’ SPSS macro Process (2013). The unstandardised and standardised regression coefficients as well as the semi‐partial squared (sr2) correlations for the analysis are in Table . Target sport intensity, prosocial peers, risky peers, gender, and year level explained a significant 23.5% of the variance in externalising behaviours (F(5, 1,188) = 73.02, p < .001). Males and students in Grade 9 reported significantly higher levels of externalising behaviours. A higher proportion of risky peers was also significantly associated with more frequent externalising behaviours. More hours of participation in the target sport and the proportion of prosocial peers were not significantly related to externalising behaviours. The addition of the three two‐way interaction terms at the second step of the analysis made a significant additional contribution to the explanation of externalising behaviours (R chg2 = .01, F chg(3, 1,185) = 2.76, p = .041), however, none of the individual interaction terms had a significant and unique association with externalising behaviours.

Table 2. A moderated multiple regression analysis investigating the associations between sporting intensity, prosocial peers, risky peers, gender, and year level on externalising behaviours for the participants engaging in sports (N = 1,194)

At the third step of the analysis, the three‐way interaction between target sport intensity, prosocial peers, and risky peers explained an additional 1.1% of the variance in externalising behaviours (F chg(1, 1,184) = 17.26, p < .001). Simple Slopes analysis was used to probe the significant three‐way interaction by examining the two‐way interaction of target sport intensity and prosocial peers at differing levels of risky peers. Analyses of the interaction between target sport intensity and prosocial peers at different levels of risky peers indicated that the relationship between target sport intensity and externalising behaviours was moderated by prosocial peers only when there were high levels of risky peers (B = − .02, p = .003) and not when there were moderate (B = − .01, p = .484) or low (B = .01, p = .272) levels of risky peers.

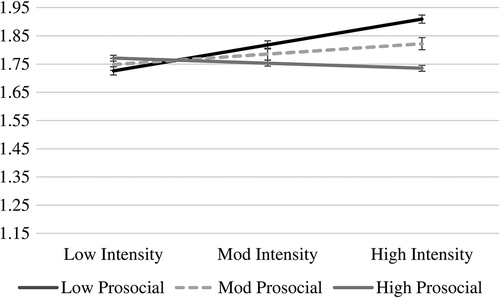

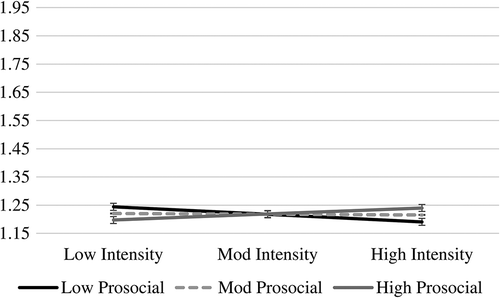

The relationship between target sport intensity and externalising behaviours, when there were high levels of risky peers (Fig. 1), was moderated by prosocial peers. The first simple slopes, at high levels of risky peers, revealed that the relationship was only significant when there were also low levels of prosocial peers (B = .02, p = .001). At moderate (B = .01, p = .092) and high (B < − .01, p = .530) levels of prosocial peers there was no significant relationship between target sport intensity and externalising behaviours. Target sport intensity was not significantly related to externalising behaviours when there were low or moderate levels or risky peers, irrespective of the level of prosocial peers. At moderate levels of risky peers, the second simple slopes analysis found no significant relationship between target sport intensity and externalising behaviours at low (B = .01, p = .287), moderate (B = .01, p = .391), or high (B < .01, p = .898) levels of prosocial peers. Similarly, at low levels of risky peers (Fig. 2), the third simple slopes analysis indicated that target sport intensity was not significantly related to externalising behaviours irrespective of whether there was low (B = −.01, p = .450), moderate (B = −.01, p = .913) or high (B = .01, p = .465) levels of prosocial peers.

DISCUSSION

The current study examined the conditional effects of prosocial and risky peers on the association between intensity of sporting participation in adolescence and externalising behaviours among adolescent sport participants. The current study adds to the existing literature by examining the interplay of both prosocial and risky peers concurrently. Contrary to the first hypothesis, more time spent engaging in sport was not associated with more frequent externalising behaviours. The contradiction of the first hypothesis is consistent with some previous studies examining outcomes of sports participation (Fredricks & Eccles, Citation2006) and inconsistent with others (Begg et al., Citation1996; Kelley & Sokol‐Katz, Citation2011). The findings from the current study advance the existing literature by finding that the characteristics of co‐participants are important aspects of the proposed link between sports participation and externalising behaviours. Although previous studies have examined the association between sports participation and externalising behaviours, the findings from the current study suggest that the characteristics of the sporting environment are important as the bivariate correlation between sport participation intensity and externalising behaviours was significant. It was only when prosocial and risky peers were added to the equation, together with the covariates, that the relationship was no longer significant. These results may indicate that the inconsistent findings in the literature could be a by‐product of heterogeneous sporting environments across schools, communities, and countries.

The second hypothesis was also supported as the association between the number of hours participating in sport and externalising behaviour was moderated by the combination of prosocial and risky peer characteristics. The link between intensity of sport participation and externalising behaviours in the presence of risk‐taking co‐participants was only present when there were few prosocial co‐participants involved in the sport. The findings suggest that peers with prosocial tendencies may buffer adolescent sport participants against potential influences of more risky peers. Additionally, there was no significant association between sports participation and externalising behaviours when the co‐participants had moderate or low levels of risk behaviours. The levels of externalising behaviours were low when the peers had fewer risky attributes, and with such low levels, there was likely less room to demonstrate a protective role of prosocial peers. The results are generally consistent with the work of Haynie (Citation2002), who found that the combination of peers with risk attributes and few peers with protective attributes lead to increases in externalising behaviours. However, the current study specifically applied this work to sporting contexts.

These results illustrate that affiliation with prosocial peers may buffer sport participants from the potential negative influence of risky peers thereby mitigating the potential for sports participation to be associated with externalising behaviours. Under these circumstances, adolescents engaging in sports with prosocial peers may be exposed to the other well‐documented benefits of participating in sport, without the potential negative consequences linked to susceptibility to externalising behaviour (Barber et al., Citation2010). Additionally, the inconsistency in the literature surrounding the association between sports participation and externalising behaviours may be due to the association being dependent on characteristics of co‐participants. As we have shown, the protective, or risky attributes of co‐participants may contribute to a context that has the potential to exacerbate, or alternatively to dampen sport participants’ engagement in externalising behaviours.

The current study exclusively examined sport participants and their perceptions of their sporting peers. The rationale for this sample is that sporting environments have been demonstrated to facilitate the formation of friendships, shared experiences, and teamwork (Barber et al., Citation2010; Fredricks & Simpkins, Citation2013). The implication of this social dynamic is that sports participation can be a risk factor for externalising behaviours when the sporting environment directly exposes adolescents to more risky peers and fewer prosocial peers. However, we acknowledge an alternative explanation is that adolescents engage in a sporting activity because their existing peer network also participates, and sporting participation ‘effects’ are partially a by‐product of existing social influences on behaviour. Academically oriented adolescents may self‐select into sporting environments populated by other academically inclined peers and fewer risky peers. For example, if a sporting team is known to be populated by risk‐taking players, externalising behaviours may become more normative, particularly if fewer prosocial peers are attracted to such a team.

Unfortunately, the cross‐sectional design of the current study precluded any casual conclusions regarding these alternative explanations. Similarly, despite proposing that time spent in a sporting environment can lead to externalising behaviours depending upon the attributes of co‐participants, the cross‐sectional design of the current study prevents a causal conclusion. Previous research using longitudinal analyses have found that time in sport can be related to changes in developmental outcomes (e.g., Barber, Eccles, & Stone, Citation2001; Denault & Poulin, Citation2009). However, it is also possible that adolescents who enjoy risk‐taking behaviours may seek out sporting environments. Sporting activities often have levels of competition and aggression (Crabbe, Citation2000) which may serve as an appealing feature to adolescents who engage in other aggressive and anti‐social behaviours. Future studies that aim to investigate temporal effects should follow adolescent sports participants over time and track the nature of the peers with to whom they come into contact with.

A second methodological limitation of the current study is the measurement of externalising behaviours through a self‐report instrument. Despite claims that self‐reported measures of externalising behaviours are both accurate and sensitive (Van der Ende & Verhulst, Citation2005), more critical views have also been advanced. Social desirability biases and the potential for the inaccurate reporting of externalising behaviours have been argued to reduce the validity of self‐report measures (McKnight, McKnight, Sidani, & Figueredo, Citation2007). Despite potentially limiting the study, self‐report measures of externalising behaviours are routinely used in the literature and have been demonstrated to be valid and reliable (Eccles & Barber, Citation1999; Eccles, Barber, Stone, & Hunt, Citation2003; Fredricks & Eccles, Citation2005; Kelley & Sokol‐Katz, Citation2011).

In conclusion, sport is a normative aspect of adolescent life in Australia. Tremendous benefits for healthy and successful developmental pathways have been shown for sports participants (Barber et al., Citation2010). However, these advantages can be potentially undermined in risky sporting contexts. Parents and coaches should have some assurance that their children can reap the benefits of active participation in the sporting community while also avoiding risks if attention is given to the attributes of co‐participants. Our study suggests that affiliation with risk‐taking fellow sport participants predicts more risk behaviours, unless there is a strong population of prosocial peers. Affirmation of prosocial norms among sport participants and attracting positively minded co‐participants to teams could tip the balance towards a more prosocial sporting culture. Such a consideration may be especially important in more disadvantaged, or high‐risk settings, in which sports are delivered to youth.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Youth Activity Participation Study of Western Australia (YAPS‐WA) was supported through three Grants under the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme: DP0774125 and DP1095791 to Bonnie Baber and Jacquelynne Eccles, and DP130104670 to Bonnie Barber, Kathryn Modecki, and Jacquelynne Eccles. The authors would like to thank all high school principals, staff, and students who took part in the YAPS‐WA study. They would also like to thank Kathryn Modecki and the YAPS‐WA team.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Abbott, B. D., & Barber, B. L. (2011). Differences in functional and aesthetic body image between sedentary girls and girls involved in sports and physical activity: Does sport type make a difference? Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 12, 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.10.005

- Barber, B. L., Eccles, J. S., & Stone, M. R. (2001). Whatever happened to the jock, the brain, and the princess? Young adult pathways linked to adolescent activity involvement and social identity. Journal of Adolescent Research, 16, 429–455. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558401165002

- Barber, B. L., Stone, M. R., & Eccles, J. S. (2010). Protect, prepare, support, and engage: The roles of school‐based extracurricular activities in students’ development. In J. L. Meece & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Handbook of research on schools, schooling, and human development. (pp. 366–378). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Begg, D., Langley, J., Moffit, T., & Marshall, S. (1996). Sport and delinquency: An examination of the deterrence hypothesis in a longitudinal study. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 30, 335–341. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.30.4.335

- Blomfield, C., & Barber, B. (2010). Australian adolescents' extracurricular activity participation and positive development: Is the relationship mediated by peer attributes? Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology, 10, 114–128.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1995). Developmental ecology through space and time: A future perspective. In P. Moen, G. Elder, & K. Luscher (Eds.), Examining lives in context: Perspectives on the ecology of human development. (pp. 619–647). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10176-018

- Crabbe, T. (2000). A sporting chance? Using sport to tackle drug use and crime. Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy, 7(4), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/dep.7.4.381.391

- Denault, A. S., & Poulin, F. (2009). Intensity and breadth of participation in organized activities during the adolescent years: Multiple associations with youth outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 1199–1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9437-5

- Drane, C. F., & Barber, B. L. (2016). Who gets more out of sport? The role of value and perceived ability in flow and identity‐related experiences in adolescent sport. Applied Developmental Science, 20, 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2015.1114889

- Eccles, J. S., & Barber, B. L. (1999). Student council, volunteering, basketball, or marching band: What kind of extracurricular involvement matters? Journal of Adolescent Research, 14, 10–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558499141003

- Eccles, J. S., Barber, B. L., Stone, M., & Hunt, J. (2003). Extracurricular activities and adolescent development. Journal of Social Issues, 59, 865–889. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0022-4537.2003.00095.x

- Flannery, D., Rowe, D., & Gulley, B. (1993). Impact of pubertal status, timing, and age on adolescent sexual experience and delinquency. Journal of Adolescent Research, 8, 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/074355489381003

- Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2005). Developmental benefits of extracurricular involvement: Do peer characteristics mediate the link between activities and youth outcomes? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 504–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-8933-5

- Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2006). Is extracurricular participation associated with beneficial outcomes? Concurrent and longitudinal relations. Developmental Psychology, 42, 698–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.698

- Fredricks, J. A., & Simpkins, S. D. (2013). Organized out‐of‐school activities and peer relationships: Theoretical perspectives and previous research. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2013(140), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20034

- Gardner, M., Roth, J., & Brooks‐gunn, J. (2008). Adolescents’ participation in organized activities and developmental success 2 and 8 years after high school: Do sponsorship, duration, and intensity matter? Developmental Psychology, 44, 814–830. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.814

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91, 481–510. https://doi.org/10.1086/228311

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Haynie, D. L. (2002). Friendship networks and delinquency: The relative nature of peer delinquency. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 18, 99–134. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015227414929

- Hinshaw, S. P. (1992). Externalizing behavior problems and academic underachievement in childhood and adolescence: Causal relationships and underlying mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 127–155.

- Kelley, M., & Sokol‐katz, J. (2011). Examining participation in school sports and patterns of delinquency using the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Sociological Focus, 44, 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380237.2011.10571389

- Lisha, N. E., Crano, W. D., & Delucchi, K. L. (2014). Participation in team sports and alcohol and marijuana use initiation trajectories. Journal of Drug Issues, 44, 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022042613491107

- Mcknight, P., Mcknight, K., Sidani, S., & Figueredo, A. (2007). Missing data: A gentle introduction. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Modecki, K., Barber, B., & Eccles, J. (2014). Binge drinking trajectories across adolescence: For early maturing youth, extra‐curricular activities are protective. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54, 61–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.032

- Overbeek, G., & Andershed, A. (2011). Girls’ problem behaviour: From the what to the why. In M. Kerr, H. Stattin, R. Engels, G. Overbeek, & A. Andershed (Eds.), Understanding girls' problem behavior: How girls' delinquency develops in the context of maturity and health, co‐occurring problems, and relationships. (pp. 1–7). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Shulruf, B. (2010). Do extra‐curricular activities in schools improve educational outcomes? A critical review and meta‐analysis of the literature. International Review of Education, 56, 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-010-9180-x

- Simpkins, S. D., Eccles, J. S., & Becnel, J. N. (2008). The mediational role of adolescents' friends in relations between activity breadth and adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1081–1094. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1081

- Van der ende, J., & Verhulst, F. (2005). Informant, gender and age differences in ratings of adolescent problem behaviour. European Journal of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 14, 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-005-0438-y

- Vernon, L., Modecki, K. L., & Barber, B. L. (2018). Mobile phones in the bedroom: Trajectories of sleep habits and subsequent adolescent psychosocial development. Child Development, 89, 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12836