Abstract

Objective

During the 2014 Brisbane G20 meeting, new police powers enabled segregation of protesters into specific protest alliances and groups. This study used this unique context to quantitatively test the Elaborated Social Identity Model of crowd behaviour (ESIM) with protesters in vivo. We did this by examining how protesters’ social identification (own protest group and protesters more broadly) predicted perceived police threat and moral justification of violence.

Method

Protesters completed survey measures of social identification, threat appraisals of police, and moral justification of violence.

Results

Mediation analyses revealed identification with superordinate group (protesters generally), but not own protest group, predicted justification of violence via threat appraisals.

Conclusions

This study presents survey data from protesters at G20. The findings support ESIM and highlight that protesters may appraise police as threatening and consider violence morally justified, even in the context of a generally well regarded and effective community‐based policing strategy.

Funding information UQ Graduate School International Travel Award; UQ Postgraduate Research Scholarship

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS TOPIC

Brisbane G20 involved one of the largest peacetime mobilisations of policing resources in Australian history.

G20 meetings often attract mass protests and present challenges for enforcement agencies and regulators.

Protester–police interactions can escalate protest into violence, but previous research has tended to be qualitative in nature.

WHAT THIS TOPIC ADDS

This study presents the quantification of a novel ESIM‐derived hypothesis with in vivo data from protesters at Brisbane G20.

Identification with protesters predicted perceived police threat, which predicted moral justification of violence.

For managing crowd risk, this highlights the need to consider social psychological factors in addition operational data such as arrests.

INTRODUCTION

The Group of Twenty (G20) leaders’ meeting is an international event of global political and social significance. As a focal point for transnational economic policy decision‐making, these high‐profile forums attract extensive media coverage (Greer & McLaughlin, Citation2010) and provide a platform for protest groups to bring worldwide attention to their causes and concerns. However, G20 meetings have also been a flashpoint for violence (e.g., 2010 Toronto summit, 2017 Hamburg summit) as protest groups and authorities jostle in service of potentially competing goals and objectives.

The Elaborated Social Identity Model of crowd behaviour (ESIM; Drury & Reicher, Citation2000; Reicher, Citation2001) describes the process through which interactions between the crowd and police can escalate into violence. According to this model, conflict between a crowd and police can arise when the crowd collectively perceives police actions to be illegitimate. In turn, this prompts crowd members to develop a more expansive self‐categorisation that can include more radical elements of the crowd, creating norms which legitimise the use of violence.

In this study, we used the unique context of the Brisbane G20 meeting, where multiple protest groups attended the meeting but were divided by authorities based on their protest group, to quantitatively test the ESIM in vivo. In doing so, we (a) tested whether the model held with a novel methodological approach in real time, (b) captured this expansive self‐categorisation by examining identification with protesters more broadly, compared to identification with protesters’ own group, and (c) combined morality and crowd behaviour literatures by examining the moral justification for violence as our focal outcome measure. We predicted that identification with protesters more broadly (but not own protest group) would be associated with moral justification of violence through increased perceptions of threat from the police. Below we elaborate on the role social identities play in the crowd before describing how the Brisbane G20 meeting allowed us to quantitatively test the ESIM.

Social identities in the crowd

The social identity approach provides a lens to examine collective action in a global context (Rosenmann, Reese, & Cameron, Citation2016). The social identity approach comprises social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979) and self‐categorisation theory (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherall, Citation1987; Turner, Oakes, Haslam, & McGarty, Citation1994) and proposes that social groups dynamically inform our concept of self, relative to others (Ellemers, Spears, & Doosje, Citation2002). Social group memberships guide our understanding of shared norms and values, facilitate effective communication, and satisfy global psychological needs (Greenaway, Cruwys, Haslam, & Jetten, Citation2015; Greenaway, Wright, Willingham, Reynolds, & Haslam, Citation2015).

Specifically in relation to protest, identifying as a group member predicts willingness to engage in collective action (van Zomeren, Postmes, & Spears, Citation2008), and in turn, undertaking collective action on behalf of that group galvanises identification (Klandermans, Citation2002). Crucially, subjective self‐categorisation and identification carries predictive value—rather than a person's objective or externally observable membership in a given social category (e.g., white, female, Australian), the boundaries of which may themselves be contested and malleable (Reicher & Hopkins, Citation1996).

Early crowd theories painted the crowd as irrational, homogenous, and unpredictable (Le Bon, Citation1896; see Drury & Stott, Citation2011, for review). In contrast, social identity approaches to crowd behaviour place a greater emphasis on the functions and legitimacy of collective gatherings in a social space (Drury & Stott, Citation2011; Stott & Drury, Citation2016; Stott & Reicher, Citation1998). Specifically, the ESIM (Drury & Reicher, Citation2000; Reicher, 2001) acknowledges that most people engage in protest with legitimate and peaceful objectives; most people who go to a rally are moderate members of the community, who believe that they are asserting their legitimate right to protest and understand police presence as a neutral guarantor of social order. This approach considers the crowd in protest as a product of vibrant and functional pluralist societies, rather than representing a risk to fragile societal fabric. It implies that when authorities take a facilitating role towards lawful peaceful protest, escalation of protests into conflict and violence is less likely to occur. Based on ESIM, facilitative police responses such as community engagement have been identified as a key intervention point for effective and safe crowd behaviour management (Drury & Stott, Citation2011; Hoggett & Stott, Citation2010; Stott & Reicher, Citation1998).

ESIM also explains how intergroup interactions between protesters and police can promote opposition, particularly how police responses to protesters can shape these interactions. Police may approach (or be perceived to approach) protesters as an illegitimate gathering or a threat to social order, and may take steps to address perceived disruption of order by suppressing or preventing protest activities. Police may be empowered to curtail protesters’ behaviours in substantial ways (kettling protesters, using pepper spray) or subtle ways (declining to display or disclose police identification number) that symbolically delegitimise lawful protest. In turn, policing activity can inadvertently increase the likelihood of protesters becoming more oppositional towards the police (Stott & Drury, Citation2016). In such circumstances, escalation into conflict and violence is more likely to occur.

Crucially, the perception that an outgroup is preparing to engage in unjust aggression can lead to individuals and groups believing that violence in response is morally justified (Bandura, Citation2004; Sterba, Citation1998). In other words, based on ESIM, when the crowd perceives police behaviour to be illegitimate and indiscriminate, this may prompt the crowd to develop a more inclusive ingroup self‐category, which may legitimise the enactment of new (more radical) norms endorsing conflict as a necessary and justified response. ESIM proposes that this shift may confirm perceptions that the crowd is hostile and illegitimate, initiating and sustaining conflict between the two groups.

Much of the previous research on ESIM is qualitative in nature (see, e.g., Drury & Reicher, Citation1999, Citation2000; Reicher, Citation1984; Stott & Drury, Citation2000). For example, Drury and Reicher (Citation2000) used an ethnographic approach to investigate the No M11 Link Road Campaign in London from 1993 to 1994. This campaign protested the M11 extension through the London districts of Wanstead, Leytonstone, and Leyton, and culminated in a protest against the removal of a chestnut tree in George Green, Wanstead. Participant accounts before and after the protest were examined, as well as biographical material. The authors found support for ESIM, such that the Wanstead residents initially saw their actions as legitimate and separate from other “activists,” but the police perceived (and responded to) the crowd as a threat to public order. This encouraged the residents to perceive that police saw their presence as illegitimate, prompting escalation.

In short, ESIM provides a model of what may happen when a crowd forms in the context of contested identities, with particular reference to conflict escalation. The 2014 Brisbane G20 meeting provided a unique context in which we were able to quantitatively test the role social identities play in the ESIM.

The 2014 Brisbane G20 meeting

At the Brisbane G20 meeting in 2014, temporary legislative provisions were enacted to regulate all public movement within specified zones (G20 (Safety and Security) Act 2013 [Qld]). Pre‐existing legislation supporting peaceful assembly was suspended and replaced with a dedicated legislative framework that stipulated a process for organisation of lawful protest. This resulted in each protest group being allocated a specific time and place during which they could protest—in essence, dividing the traditional “crowd” corpus into small groups. The associated policing strategy deployed at the Brisbane G20 also involved a combination of facilitative police support and engagement for specific registered groups, alongside general enforcement against G20 opponents or disruptors.

This regulatory intervention created an ideal testing‐ground for social psychological theories of crowd behaviour and collective action. Specifically, the Brisbane G20 protests brought together diverse groups to collectively protest at G20; but also siphoned protesters into specific interest groups across different designated protest spaces around the city centre. These spaces were large, public, inner city locations, cordoned off specifically for protests and other G20 activities to take place. For example, while some protests were scheduled to take place at the Roma Street Parklands, other groups were allocated a different space and time at the Southbank precinct. Therefore, the arrangements created an opportunity in which protesters could readily identify with their immediate protest group (i.e., “I am here with my protest group”), as well as a superordinate category of G20 protesters more broadly (i.e., “we are all protesters here at G20”).

For these reasons, the Brisbane G20 environment made it possible to examine how two forms of group identification could predict how protesters navigate the socio‐political space of protest. In particular, we examined the role of these identities in vivo in predicting how people appraise other groups (such as police); and how protesters determine appropriate and justifiable conduct for themselves in the protest context (i.e., violence or peacefulness). We therefore sought to quantitatively test ESIM and examine two different forms of social identification with other protesters—identification with one's own protest group, and identification with other protesters more broadly. In this novel environment, we anticipated that identification with the broader protester bloc may serve as an index of the emergent oppositional identity described by ESIM (i.e., an oppositional identity towards the police), because while individually registered groups received facilitative police contact and support, the broader protest en mass remained the target of upscaled police enforcement efforts.

Threat appraisals

A key process in the interplay foreshadowed by ESIM is how protesters themselves appraise police (i.e., facilitative or delegitimising). On one hand, as part of the Brisbane G20 policing strategy, dedicated police liaison officers were assigned to negotiate with registered protest groups up to 18-months in advance of the G20 meetings and during the event, with a view to engendering trust and facilitating lawful protest (Legrand & Bronitt, Citation2015; Walsh, Citation2016). On the other hand, police were granted greatly expanded powers to search and arrest; and with approximately 6,000 police deployed, independent observers noted the potential for substantial outnumbering of members of the public by police and a “pervading sense of personal insecurity” (Caxton Legal Centre, Citation2014, p. 17). In this context, predictors of intergroup opposition foreshadowed by the ESIM could be measured—would all protesters appraise police as threatening and delegitimising, or facilitative? We earlier proposed that identification with other protesters may serve as an indicator that an oppositional identity is, or has been, built (Drury & Reicher, Citation2000). Specific registered protest groups also received enhanced police communication and engagement under the community policing approach. Based on ESIM, facilitative policing should attenuate protesters’ perception of threat from police—but facilitative efforts were targeted at specific groups, and the crowd was physically partitioned into these smaller sub‐groups. We surmise that the conditions at the G20 potentiated threat appraisals for those who identified with the superordinate group. On this basis, we therefore expected that superordinate identification (identification with protesters generally) would predict higher threat appraisals of police, but that identification with one's own protest group would not.

Moral justification of violence

When do protesters consider violence to be morally justified? As noted, protesters’ appraisals of police threat are an important component in the conflict escalation pathway predicted by ESIM. History indicates that protests can be a fraught and even dangerous undertaking for protesters (see, e.g., Ayanian & Tausch, Citation2016). Traditional policing responses emphasised threat and use of force to control the crowd (Drury & Reicher, Citation2000; Drury & Stott, Citation2011; Hoggett & Stott, Citation2010); however, this policing model has been increasingly superseded by “negotiated management” approaches that aim to build community relationships, de‐escalate conflict, and legitimise the act of protest. These practice shifts have most notably been seen in the UK (Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC), Citation2009a, Citation2009b), but also in Australia (Legrand & Bronitt, Citation2015; Walsh, Citation2016) and other liberal democracies (see, e.g., Stott, Adang, Livingstone, & Schreiber, Citation2008).

The ESIM model argues that when the crowd perceives the behaviour of the police as threatening and illegitimate, crowd members come to see themselves as part of a common category which includes more radical elements of the crowd that may have previously been marginalised. Moreover, agreement about what is right and wrong has an identity defining function (Ellemers & van den Bos, Citation2012). This extension and unification of the ingroup leads to empowerment and the perception that challenging the police is legitimate, which can be expressed in the form of violence (Reicher, 2001).

Importantly, not all conflict in protest escalates into violence. In the current work, we extend the ESIM to show that moral justification of violence is a novel way in which researchers can tap into the willingness of protesters to challenge the police as an index of the creation of new norms of conflict, and in doing so, expand the ESIM to the domain of morality. Engaging in violent behaviour can be perceived to be a morally legitimate course of action if an individual or group believe they are acting in defence against an opposition preparing to engage in unjust aggression (Sterba, Citation1998). This argument dovetails with the work of Bandura (Citation2004), who noted that “[p]eople do not ordinarily engage in reprehensible conduct until they have justified to themselves the morality of their actions…destructive conduct is made personally and socially acceptable by portraying it as serving socially worthy and moral purposes… Moral justification sanctifies violent means.” (p. 124)

Inherent in Bandura's (Citation2004) discussion of moral justification for violence is the role of legitimacy of one's action—that people do not engage in violent behaviours unless they have deemed it to be socially acceptable in one form or another. This can be tied to the ESIM model which proposes that perceived illegitimacy of police actions creates a more inclusive social identity, and which makes it legitimate for protesters to enact more violent norms. Indeed, both moral outrage (Saab, Tausch, Spears, & Cheung, Citation2015) and perceived moral conviction (van Zomeren, Postmes, Spears, & Bettache, Citation2011) have been identified as antecedents of collective action, and may even act as a catalyst for extreme sacrificial behaviour to benefit others (Crimston & Hornsey, Citation2018). Moreover, when attitudes are held with deep moral conviction, disagreement can manifest in the form of increased intolerance, and reduced levels of good will and cooperation (Skitka, Bauman, & Sargis, Citation2005). In short, considering moral justification of violence in protest is worthwhile because it represents a nuanced psychological manifestation of intergroup conflict escalation in protest, which is complementary with ESIM and can be operationalised using a measure that lies below the threshold of overt violent behaviour.

Based on this previous research, we argue that threat appraisals represent a potential mechanism by which violence may be morally justified—specifically, that threat appraisals concerning police could readily provide the psychological grounds for people to morally justify violent action, even in the context of prior negotiated legitimacy and community‐engagement policing. Further, threat is a known predictor of aggression and aggressive behaviours (Anderson & Bushman, Citation2002; Schmid, Hewstone, Küpper, Zick, & Tausch, Citation2014). Therefore, integrating these themes with ESIM, we expected that threat appraisals of police would predict the belief that violence is morally justified during the protests.

There were also pragmatic reasons to measure moral justification of violence rather than protesters’ self‐reported intentions to engage in violent protest at G20. Following the well‐publicised outbreaks of violence at the 2010 G20 summit in Toronto (Tran, Citation2010), the examination of potential violent intent among protestors was of great interest to the current research. However, in examining the escalation pathway with active protesters in the field, we were concerned not to expose participants to the risk of self‐incrimination as a result of asking people to indicate any specific intentions to engage in violent collective action at the Brisbane G20.

Current study

In the present study, we gathered survey data from individuals actively protesting at the Brisbane G20 to understand social identity patterns; how people appraised police; and how protesters determined appropriate conduct and constructed moral boundaries for themselves in the protest context. We surveyed protesters to gauge social identification, perceptions of police (threat appraisals), and beliefs about whether violence was morally justified on the day (moral justification of violence). Extending upon ESIM, we predicted that identification with the superordinate group (but not immediate protester group) would be associated with greater appraisals of police as threatening, which in turn would predict the perception that violence was morally justified.

METHOD

Participants and procedure

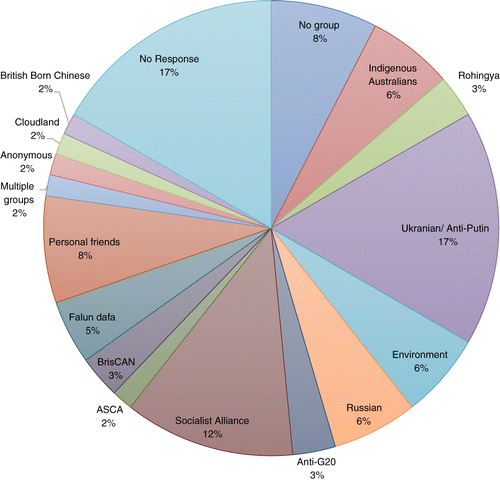

Responses were collected from 84 protesters engaging in lawful public assembly during the 2014 G20 meeting in Brisbane from a range of different protest groups (see Figure 1). Data collection and sample size were determined by practicality with a direct view to maximising the number of possible respondents, within study resources and substantial field constraints, and supporting mediation analyses involving medium effect sizes (Fritz & MacKinnon, Citation2007). Of the total 84 participants, 3 participants were excluded because they were under the age of 18 and 15 participants were excluded as they did not complete at least 50% of the items for one or more of the main variables (protester identification, threat appraisals, moral justification of violence). The final sample size consisted of 66 protesters (53% female, 42% male, 5% nil response; Mage = 33.63-years, SD = 13.03, range: 18–72-years). Protesters within declared assembly areas were approached and invited to complete the survey. No payment was offered. This study was approved by the University School of Psychology Ethics Review Committee (14‐PSYCH‐PHD‐65‐JS).

Materials and measures

The questionnaire included a series of measures adapted for the G20 context. Additional measures are unreported here for brevity.Footnote1

Protester identity. Two measures of social identification were adapted for the G20 context (Postmes, Haslam, & Jans, Citation2013). Participants rated how much they identified with their protest group (“my protest group”), and other protesters (“other protesters generally”), on a 7‐point scale (1 = not at all to 7 = very much so).

Threat appraisal. Protesters’ threat appraisals of police were assessed with five items adapted from an existing measure of threat and challenge appraisals (Ferguson, Matthews, & Cox, Citation1999). This measure captured perceived threat associated with police presence (α = 0.87) on a 7‐point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree; e.g., “I see the presence of the police as: hostile, worrying, frightening, threatening, intolerable”).

Moral justification of violence. Subjective moral justification of violence was assessed using four items on a 7‐point scale (1 = never justified to 7 = always justified; e.g., “For yourself today, to what extent is it morally justified to be: violent, aggressive, forceful, hostile”; α = 0.84).

RESULTS

Variables were screened for outliers and violations of assumptions. Descriptive statistics and zero‐order correlations are summarised in Table . We conducted mediation analyses based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples using bias‐corrected and accelerated 95% confidence intervals with the PROCESS macro (model 4) for SPSS 20 (Hayes, Citation2013).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for identification, threat appraisal, and moral justification variables (N = 66)

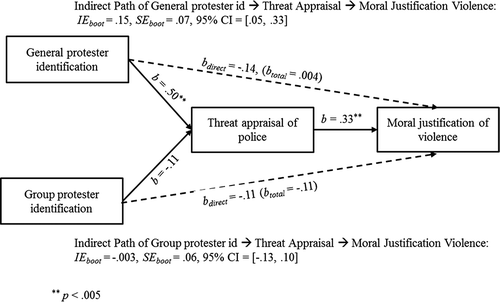

To assess our main hypothesis, we tested a dual mediation model with pathways from identification (protesters generally and own protest group entered as predictors) to moral justification of violence (entered as criterion) via police threat appraisal (entered as mediator; see Figure 2).Footnote2 We specifically tested indirect effects of identification on moral justification via threat appraisals (with bootstrapping), rather than undertaking the Baron and Kenny (Citation1986) causal steps approach (Hayes, Citation2013). Using this approach, a relationship between the predictor and criterion is not required (Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, Citation1998; MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, Citation2007). In line with Hayes’ (Citation2013) recommendations, to run a mediation model with two independent variables and obtain two indirect effects, we ran the PROCESS macro for each predictor including the other predictor as a covariate.

Identification with protesters generally significantly predicted police threat appraisal, b = 0.50, SE = 0.15, t(63) = 3.23, p = 0.002, 95% confidence interval (CI) [0.19, 0.80], such that higher identification was associated with appraising the police as more threatening. However, identification with own protest group did not significantly predict police threat appraisal, b = −0.11, t(63) = −0.07, p = 0.944, 95% CI [−0.33, 0.31]. Approximately 15% of the variance in police threat appraisal was accounted for by the predictors (R2 = 0.15, F [2, 63] = 5.46, p = 0.007). Police threat appraisal was significantly related to moral justification of violence, b = 0.30, t(62) = 2.96, p = 0.004, 95% CI [0.10, 0.50] (after controlling for identification). The overall model was significant, with the predictors explaining 13% of the variance in moral justification of violence (R2 = 0.13, F [3, 62] = 3.18, p = 0.030). In accordance with our predictions, there was a significant indirect effect of protester identification on moral justification of violence via police threat appraisal (B = 0.15, B SE = 0.07, 95% CI [0.05, 0.33]). After accounting for the indirect effect, there was no direct effect of general protester identification or group protester identification on moral justification of violence, b = −0.14, SE = 0.13, t(63) = −1.08, p = 0.172 and b = −0.11, SE = 0.13, t(63) = −0.86, p = 0.395, respectively. The total effect model was not significant, R2 = 0.01, F (2, 63) = 0.36, p = 0.700).

DISCUSSION

The current study provides the only snapshot of protester identification, appraisals, and moral justification for violence during a major international policing operation—the Brisbane G20. We measured two different social identification profiles (immediate group and superordinate group identification) and expected these identities to have important, and differing, implications for how protesters might come to perceive violence to be a morally justifiable behaviour. We found identification with G20 protesters (but not own protest group) predicted the appraisal of police as threatening, which in turn predicted the perception that violence was morally justified.

This study adds to existing ESIM literature in a number of ways. First, we provide support for the model with a novel methodological approach and in real time, which is rare in the collective action literature. Second, we capitalise on the unique protesting context at the Brisbane G20 meeting to examine identification at two levels of abstraction (superordinate and subgroup identity). The regulatory and policing environment at the Brisbane G20 divided protesters into separate groups, and allocated specific times and locations throughout the city centre for lawful protest to take place. Facilitative efforts and outreach were directed towards registered protest groups, while protesters more broadly were the subject of deterrent language and displays of force in the media. The ESIM proposes that conflict between the crowd and police escalate, in part, when the crowd perceives the police's actions to be illegitimate and hostile, prompting them to develop a more inclusive ingroup identity with other crowd members that may previously have been considered too radical. Subgroup and superordinate protester identification at the Brisbane G20 meeting was one way this abstraction of identity could be captured. We proposed and found that participants who identified with protesters more broadly had already developed this more inclusive identity, which was associated with moral justification of violence through the perception of threat from the police.

The current research is in line with previous work suggesting that ingroup extension can lead to the perception that challenging authority is legitimate (Reicher, 2001), and that violent actions can be justified by individuals and groups in response to perceptions of illegitimate aggression (Bandura, Citation2004; Sterba, Citation1998). This work provides novel evidence supporting the extension of ESIM into the domain of morality, and connects recent developments in the collective action literature (the consideration of morality in protest; van Zomeren, Postmes, Spears, & Bettache, Citation2012; van Zomeren et al., Citation2013) to crowd behaviour research. Finally, we argue that measuring participants’ moral justification for violence is a novel way that researchers can tap into how protesters may be conceptualising (or even re‐conceptualising) what is acceptable conduct in response to intergroup conditions. Crucially, this approach is applicable even in no‐ or low‐violence protests, because it focused not on actual violence, but on the extent to which individual protesters felt that violence is morally justified for them on the day.

Limitations and future directions

This study examined protester appraisals of police through the prism of threat. Future research could expand on this to assess threat appraisals over time (e.g., before, during, and after protest). Longitudinal studies could confirm how intergroup dynamics are causally modulated, for example by community engagement efforts, or displays of force by police, or through media depictions of protesters and police.

It is important to note that these findings were in the context of a low‐conflict protest. The Brisbane G20 has been reported as a highly successful police enforcement operation given the very low number of arrests and persons excluded from declared zones (Baker, Bronitt, & Stenning, Citation2017; Crime and Corruption Commission Queensland, Citation2015; Queensland Police Service, Citation2015). These conditions highlight that even in the context of a generally well‐regarded and effective community‐based policing strategy, subtle cues may still enliven the oppositional pathways foreshadowed by ESIM, and indeed the threat‐violence endorsement pathway the present study describes. Other mass gatherings research has documented the utility of community policing in the context of relatively calm collective gatherings. In particular, Stott et al. (Citation2008) considered that the policing operation at the 2004 European football finals in Portugal was effective because it employed ESIM principles and facilitated non‐violent crowd management, but also in part because it “…psychologically marginalise[d] violent groups from the wider community of fans” (p. 115). Our findings invite reflection on the implications of dividing the crowd, and the potential consequences where protesters do appraise police as threatening, despite bona fide police engagement efforts. In managing risk, this study shows the need to consider psychological factors in addition operational data such as arrests.

Our study contains other limitations that should be considered when conducting future research. We are aware that our sample size limits our use of more sophisticated data analysis techniques. We are unable, for example, to model the data using structural equation modelling or multi‐level modelling to more deeply inform our research questions, such as making comparisons between specific protest groups or between site locations. Evidently, our small sample size is the product of collecting data in a highly‐charged and challenging field environment (i.e., some protesters were focused on marching rather than answering surveys; free movement was constrained). Future research should consider recruiting participants taking part in police negotiations prior to events, as well as groups who do not.

In addition, we asked questions about participants’ moral justification of violence rather than group norms, protesters’ intentions or actual participation in violence in our survey. We specifically declined to ask protesters about intentions or actual participation in violence, to avoid risks of incrimination flowing from study participation, which is particularly relevant in tightly‐regulated enforcement contexts such as G20. It is important to acknowledge that the moral justification of violence measure may be subject to different interpretations from the participants, and additional research could flesh out this construct using qualitative and quantitative methodologies, including the extent to which norms and moral justification of violence might overlap. Future research could also consider in vivo measures that minimise risk to participants, such as via anonymised third‐party footage of the event or other technology‐based protections, and more concrete measures of moral justification when data is collected in circumstances which carry less risk to the participants.

Moreover, we acknowledge that the cross‐sectional nature of data does not allow us to draw conclusions about causality. It is plausible (and we would probably expect) that there is a cyclic relationship between the variables examined in this study. We also acknowledge the possibility that alternative models exist that may also fit the data. Although the current study did not find evidence supporting a reverse model (i.e., in which threat predicts expansive identification), the present cross‐sectional data are from a single time‐point and do not capture the effect of intergroup interactions through protest over time. Future research could consider examining collective action longitudinally over the course of a protest event, or across a series of protests to further investigate the causal and dynamic nature of the relationships we identify and how identification with protesters more broadly develops over time. Such research might reveal an effect of threat on identification over time (over the course of a single protest event, or even perhaps over multiple protests), consistent with the escalation/facilitation dynamic envisaged by ESIM.

The reader might ask why the protesters did not become violent given that participants who identified with protesters more broadly reported increased moral justification to be violent. While the current research does not permit a conclusive stance to be made, we might speculate that by breaking up the crowd, the potential for protesters to act as a superordinate group en masse was undermined. An alternative explanation is that by attending the G20 meeting, protesters were still able to experience empowerment (i.e., confidence in their ability to challenge existing relations) by enacting their social identity at the event (Drury & Reicher, Citation2005). This expression of social identity, which Drury and Reicher (2005) call collective self‐objectification, is not dependent upon success or failure in terms of protest outcomes. Therefore it is possible that just the act of attending the protest may be perceived to be a “victory” in the eyes of the protesters, superseding other outcomes (such as becoming violent). Future research is required however to substantiate these arguments.

Finally, protesters’ appraisals of other groups in vivo provide crucial empirical feedback to police and regulators on how their efforts are perceived. With this approach, precursors and intervention points for de‐escalation and community engagement can be further explored. The implication is that police may wish to manage risks by further refining and targeting outreach strategies, and to consider the potential benefits of reducing “show of force” tactics with the knowledge that some protesters can and do interpret such tactics as providing a moral justification for themselves to be violent.

CONCLUSIONS

This research investigated protester identification, police appraisals, and moral justification of violence at the Brisbane G20 meeting, by utilising and extending the theoretical framework provided by ESIM. We found that the extent to which protesters identified with G20 protesters broadly was indirectly associated with the moral justification for violence via threat appraisals of police. These findings make a quantitative and unique contribution to the growing literature that supports the ESIM. Ultimately, these findings have strategic implications for policing research, policy, and practice, in order to support policing interventions and operations that seek to maintain community safety while allowing protesters the right to voice their opinion. Our results support the continuation of negotiated coordination with protest groups, but also highlight that oppositional identity patterns may not be ruled out through current approaches to targeted community consultations alone.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded with the support of a UQ Graduate International Travel Award and UQ Postgraduate Research Scholarship awarded to Laura Ferris. We would like to thank Professor Jolanda Jetten, Professor Alex Haslam, and Dr. Clifford Stott for their insight, guidance, and feedback.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

Funding information UQ Graduate School International Travel Award; UQ Postgraduate Research Scholarship

1. The survey also measured the following variables excluded for brevity, not specifically relevant to the current hypotheses, or for which there was a high proportion of missing data: appraisals of G20 itself and other protesters, moral justification of peacefulness and violence relevant to other protesters’ behaviour, protest efficacy, political orientation, identity fusion, media depictions of police and protesters, and qualitative open‐ended questions (such as rationale for being at G20 protests).

2. As the data were cross‐sectional in nature, reverse mediations were also conducted (including the pathway from police threat appraisals ➔ identification with protesters more broadly ➔ moral justification for violence) to examine alternative explanations. None of the reverse indirect effects were significant, and thus are not reported here.

REFERENCES

- Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 27–51. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231

- Ayanian, A. H., & Tausch, N. (2016). How risk perception shapes collective action intentions in repressive contexts: A study of Egyptian activists during the 2013 post‐coup uprising. British Journal of Social Psychology, 55(4), 700–721.

- Baker, D., Bronitt, S., & Stenning, P. (2017). Policing protest, security and freedom: The 2014 G20 experience. Police Practice and Research, 18(5), 425–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2017.1280674

- Bandura, A. (2004). The role of selective moral disengagement in terrorism and counterterrorism. In F. M. Moghaddam & A. J. Marsella (Eds.), Understanding terrorism: Psychosocial roots, consequences, and interventions (pp. 121–150). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator‐mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

- Caxton Legal Centre. (2014). Report to the Crime and Corruption Commission Queensland: Review of the G20 (Safety and Security) Act 2013. Retrieved from https://caxton.org.au/pdfs/G20%20Review%20submission.pdf

- Crime and Corruption Commission Queensland. (2015). Review of the G20 (Safety and Security) Act 2013: Consultation paper and invitation for public submissions.

- Crimston, C., & Hornsey, M. J. (2018). Extreme self‐sacrifice beyond fusion: Moral expansiveness and the special case of allyship. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 41, e198. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X18001620

- Drury, J., & Reicher, S. (1999). The intergroup dynamics of collective empowerment: Substantiating the social identity model of crowd behavior. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 2(4), 381–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430299024005

- Drury, J., & Reicher, S. (2000). Collective action and psychological change: The emergence of new social identities. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39(4), 579–604. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466600164642

- Drury, J., & Reicher, S. (2005). Explaining enduring empowerment: a comparative study of collective action and psychological outcomes. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35(1), 35–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.231

- Drury, J., & Stott, C. (2011). Contextualising the crowd in contemporary social science. Contemporary Social Science, 6(3), 275–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2011.625626

- Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (2002). Self and social identity. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 161–186. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135228

- Ellemers, N., & van den Bos, K. (2012). Morality in groups: On the social‐regulatory functions of right and wrong. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(12), 878–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12001

- Ferguson, E., Matthews, G., & Cox, T. (1999). The appraisal of life events (ALE) scale: Reliability and validity. British Journal of Health Psychology, 4(2), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910799168506

- Fritz, M. S., & Mackinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x

- Greenaway, K. H., Cruwys, T., Haslam, S. A., & Jetten, J. (2015). Social identities promote well‐being because they satisfy global psychological needs. European Journal of Social Psychology, 46, 294–307. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2169

- Greenaway, K. H., Wright, R. G., Willingham, J., Reynolds, K. J., & Haslam, S. A. (2015). Shared identity is key to effective communication. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(2), 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214559709

- Greer, C., & Mclaughlin, E. (2010). We predict a riot? Public order policing, new media environments and the rise of the citizen journalist. The British Journal of Criminology, 50(6), 1041–1059. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azq039

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression‐based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

- Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC). (2009a). Adapting to protest. Retrieved from https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/media/adapting‐to‐protest‐20090705.pdf

- Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC). (2009b). Adapting to protest: Nurturing the British model of policing. Retrieved from https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/media/adapting‐to‐protest‐nurturing‐the‐british‐model‐of‐policing‐20091125.pdf

- Hoggett, J., & Stott, C. (2010). The role of crowd theory in determining the use of force in public order policing. Policing and Society, 20(2), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439461003668468

- Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Bolger, N. (1998). Data analysis in social psychology. In D. Gilbert, S. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 233–265). Boston, MA: McGraw‐Hill.

- Klandermans, B. (2002). How group identification helps to overcome the dilemma of collective action. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(5), 887–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764202045005009

- Le bon, G. (1896/2001). The crowd: A study of the popular mind. Kitchener: Batoche Books.

- Legrand, T., & Bronitt, S. (2015). Policing the G20 protests: “Too much order with too little law” revisited. Queensland Review, 22(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/qre.2015.2

- Mackinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 593–614. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542

- Postmes, T., Haslam, S. A., & Jans, L. (2013). A single‐item measure of social identification: Reliability, validity, and utility. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(4), 597–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12006

- Queensland Police Service. (2015). Review of the G20 (Safety and Security) Act 2013. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/documents/tableOffice/TabledPapers/2015/5515T1672.pdf

- Reicher, S. (1984). The St. Pauls’ riot: An explanation of the limits of crowd action in terms of a social identity model. European Journal of Social Psychology, 14(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420140102

- Reicher, S. (2001). The psychology of crowd dynamics. In M. A. Hogg & R. S. Tindale (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Group processes (pp. 182–208). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Reicher, S., & Hopkins, N. (1996). Self‐category constructions in political rhetoric; an analysis of Thatcher's and Kinnock's speeches concerning the British miners’ strike (1984–5). European Journal of Social Psychology, 26(3), 353–371. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199605)26:3<353::AID-EJSP757>3.0.CO;2-O

- Rosenmann, A., Reese, G., & Cameron, J. E. (2016). Social identities in a globalized world: Challenges and opportunities for collective action. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(2), 202–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615621272

- Saab, R., Tausch, N., Spears, R., & Cheung, W. Y. (2015). Acting in solidarity: Testing an extended dual pathway model of collective action by bystander group members. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 54(3), 539–560. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12095

- Schmid, K., Hewstone, M., Küpper, B., Zick, A., & Tausch, N. (2014). Reducing aggressive intergroup action tendencies: Effects of intergroup contact via perceived intergroup threat. Aggressive Behavior, 40(3), 250–262. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21516

- Skitka, L. J., Bauman, C. W., & Sargis, E. G. (2005). Moral conviction: Another contributor to attitude strength or something more? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(6), 895–917. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.895

- Sterba, J. P. (1998). Justice for here and now. Cambridge studies in philosophy and public policy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Stott, C., Adang, O., Livingstone, A., & Schreiber, M. (2008). Tackling football hooliganism: A quantitative study of public order, policing and crowd psychology. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 14(2), 115–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013419

- Stott, C., & Drury, J. (2000). Crowds, context and identity: Dynamic categorization processes in the “poll tax riot”. Human Relations, 53(2), 247–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/a010563

- Stott, C., & Drury, J. (2016). Contemporary understanding of riots: Classical crowd psychology, ideology and the social identity approach. Public Understanding of Science, 26(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662516639872

- Stott, C., & Reicher, S. (1998). Crowd action as intergroup process: Introducing the police perspective. European Journal of Social Psychology, 28(4), 509–529. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199807/08)28:4<509::AID-EJSP877>3.0.CO;2-C

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Moneterey: Brooks/Cole.

- Tran, M. (2010). Hundreds arrested after G20 protesters riot in Toronto. The Guardian.

- Turner, J. C., Hogg, M., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S., & Wetherall, M. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self‐categorization theory. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Turner, J. C., Oakes, P. J., Haslam, S. A., & Mcgarty, C. (1994). Self and collective: Cognition and social context. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 454–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205002

- van Zomeren, M. (2013). Four core social‐psychological motivations to undertake collective action. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7, 378–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12031

- van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., & Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio‐psychological perspectives. Psychological Bulletin, 134(4), 504–535. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504

- van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., & Spears, R. (2012). On conviction's collective consequences: Integrating moral conviction with the social identity model of collective action. British Journal of Social Psychology, 51(1), 52–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02000.x

- van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., Spears, R., & Bettache, K. (2011). Can moral convictions motivate the advantaged to challenge social inequality?: Extending the social identity model of collective action. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14(5), 735–753. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430210395637

- Walsh, T. (2016). “Public order” policing and the value of independent legal observers. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 28(1), 33–49.