“I committed a crime when I was seven. An atlas made me do it. I stole it from my brother by simply erasing his name inside and putting mine in its place – an easy, if immoral, way to ensure that it was no longer his.

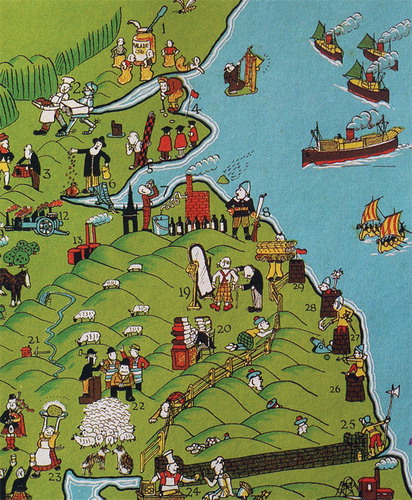

The stolen book was a children’s pictorial atlas of the British Isles, crammed with wonderful little drawings of people standing on the maps. The people were farming, mining, traveling, banking, dancing: the energy and color of the crowded pictures made everyone practically jump off the pages. I loved this atlas, and long after I should have been consulting a more grownup one, I kept going back to it for reference. That book was important to me because it made geography interesting by combining pictures of things that I could relate to – buildings, trees, and people – with the usual abstract representations of the landmasses”

Nigel Holmes, Citation1991 p1.

Figure 1. An extract from A Pictorial Atlas of the British Isles (in Holmes, Citation1991)

I graduated from my degree in cartography and geography in July 1991. Three months later, Nigel Holmes published his book ‘Pictorial Maps’. It’s remained one of my favourite books and brought together much of what I had learnt in my degree in illustrative form. It spoke to me as a compendium of work that used highly illustrative graphics, often as maps or combined with maps, to tell a story about something. That, for me, is cartography and always has been cartography.

I’ve been using the above section of Holmes’ book ever since in explaining how a love of maps, exploration and our passion for finding stuff out begins in childhood. More than that though, how we relate to maps as a mechanism that delivers this information and how they fill in the visual voids and appeal to our sense of wonderment about the world around us. Holmes has become one of the world’s foremost influencers in information graphics. His unique style has been provocative and controversial yet his is precisely the sort of work that helps us imagine how we might represent our own ideas, our own stories. He lists ‘A Pictorial Atlas of the British Isles’, published in 1937 (Alnwick, Citation1937) as one of his top ten influences in his own work. This is perhaps how we all begin our love affair with maps and the stories they tell. We begin with maps designed to appeal to us through a child’s eyes but we eventually grow up and our cognitive skills become tuned to more adult representations. At the heart of this and all good maps is a story and as a map reader we become a very important actor in the interaction with the map. Whether we’re looking at the topography of a reference sheet and exploring the detailed story of the landscape; imagining the people wandering across the children’s atlas; or interpreting what a statistical map means for people in different areas we’re doing one thing – following the narrative of the map to better understand the story it is telling. Story telling is the very essence of good map-making and good cartographers have forever been successfully telling stories. In fact, good story-tellers have made very good use of maps as vehicles for their work. Whether abstract or pictorial, good maps convey a sense of place regardless of whether you are using it to uncover some basic factual information or purely to gaze at for enjoyment.

Maps use the language of cartography to graphically structure their meaning and to concentrate people’s attention on the aspect of importance. While the language of cartography has changed very little over the years and has given us some clear guiding principles, the maps themselves have taken on many different forms. It’s intriguing, then, that current buzz words include ‘Story Maps’ and ‘Map Stories’. These tend to relate to simple, linear storytelling via web maps with ancillary content such as text and images. The maps may tell very personal stories of someone’s movement, perhaps tracing some historical journey or they may explore a single theme and allow people to interactively follow the path or the ‘top ten’ of something or other. These are really just an alternative way of telling a story through the use of maps but they’ve become popular since we now have the tools to create very personalized maps…to tell our own stories and bring our own sense of place to the spaces that are important to us. These maps live online and can be shared widely. What they do is allow people to narrate…to bring a story to life in ways that may once have been the preserve of professional cartographers. We may cringe at some of the maps and, really, some are not much more than geolocated holiday snaps, but the ability for people to create their own stories and accounts of things that are important to them has never been more prevalent. People are chronicling, commentating, documenting and creating their own spatial annals. The use of maps and blogs have become interwoven. Some reveal anecdotes, some are used as a diary and some provide a window on a space and place we may never get to see ourselves. I can lose myself for hours exploring the many thousands of such maps that get published each day in the same way that as children we poured over pictorial atlases. It’s a rich medium for communicating and sharing but isn’t there more to it than simply mapping stuff and calling it a story? Cartography as a discipline has a far greater purpose than providing people with the ability to map their holiday photos on a web map.

I was therefore delighted when Sébastien Caquard and William Cartwright AM approached The Cartographic Journal with the idea for this Special Issue. Cartography is not just about art, science and technology but also about theory and the advancement of critical thought in our discipline. This Special Issue brings exactly that dimension to the idea of narration in a map and also as a way to think of the process of map-making. In addition to their own essay on the subject, the collection of papers they have collated from leading scholars encourage us to think about the current trend in map-making in a more reflective way rather than just seeing the latest map and moving on.

I’d like to thank Sébastien and William for preparing a really excellent issue, not only for the content but also for bringing to bear a key work that helps us understand narrative cartography. This Special Issue will help us to frame the relationship between maps and the stories they tell and, importantly, about the way in which we tell those stories through the map-making process. Special issues such as this also provide a critical statement about theoretical cartography and its importance in helping to fashion guidance. Without critical reflection and a framework to guide us then our story maps, map stories (call them what you will) will end up being ill-conceived, poorly constructed and narrated in a language hard to decipher. We already see a lot of this. The articles herein set about recasting the story-telling aspect of the discipline to take us beyond the current fashion and buzz-words.

Kenneth Field

April 2014

Redlands, CA

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Dr Kenneth Field works in Cartographic Research and Development at Esri Inc and was formerly Principal Lecturer and GIS Course Director at Kingston University London. He holds a PhD in GIS from Leicester University and has presented and published widely on map design. He is a Fellow of the British Cartographic Society, Royal Geographic Society and a Chartered Geographer (GIS). He is also Chair of the ICA Commission on Map Design (mapdesign.icaci.org and @ICAMapDesign), maintains a personal blog (cartonerd.com) and tweets (@kennethfield). Don’t forget you can follow The Cartographic Journal on Twitter (@CartoJnl).

References

- Alnwick H. (1937) A Pictorial Atlas of the British Isles, George G. Harrap & Co., Ltd., London.

- Holmes N. (1991) Pictorial Maps. Watson-Guptill, New York City.