I'm a documentary filmmaker at National Geographic and am presently working on a film about ancient copper production in Faynan District in southern Jordan. The film also delves into the relationship between copper production in Faynan and the so-called Israelite United Monarchy.

This e-mail began yet another of my encounters with biblical archaeology on TV. The programme in question, produced by NOVA and called The Quest for Solomon's Mines, was broadcast in the USA on November 23rd 2010. It aimed to link copper mining with King Solomon. The transcript of the programme reads:Footnote1

The Bible tells us Solomon was not only the wisest, but the richest of all kings, but where did his wealth come from? Legends tell of fabulous mines of gold and copper, but where were they? Archaeologists have searched for evidence of Solomon and found nothing.

The archaeologist Eric Cline of George Washington University reminds the viewer that so far there is no evidence for Solomon outside the Bible, either. And, as the programme admits, there is “no conclusive archaeological proof” either. Very even-handed so far, but rather than abandon a clearly speculative line, the producers adopt the familiar circular route of proving a conclusion by assuming the premise: a royal mining magnate called Solomon. An archaeologist can always be found to make the same circular journey, and the film took us to Khirbet al Nahas in the Wady Feynan, in Jordan, and to Thomas Levy of San Diego, who was excavating a large copper mining complex with co-director Mohammad Najjar, Director of Excavations and Surveys at the Department of Antiquities of Jordan (though credited in the transcript as “University of California, San Diego Levantine Archaeology Lab”). The argument, endorsed by Levy, ran that Solomon's temple required lots of metal, including copper; and the closest source for copper was in the Wadi Feynan—whose long period of operation included the 10th century bce. As ex hypothesi the greatest king in the region at this time, Solomon must have controlled the extensive mining operations there. Amihai Mazar of the Hebrew University then comments: “I believe that if, one day, we should find the copper objects from the temple in Jerusalem, it will prove to come from this area,” which sounds like an endorsement, but reads more cautiously, avoiding the name of Solomon!

The daisychain arguments have been assembled without the legend of “King Solomon's Mines”, of course, but this legend itself is worth looking at in its own right. To begin with, it's not biblical. The accounts in Kings and Chronicles make no mention of the source of the copper (“bronze”, neḥoshet) that was wrought by Ḥiram/ḤuramFootnote2 Indeed, 1 Chronicles 18:8 points in a quite different direction: “From Tibhath and from Cun, cities of Hadadezer [king of Zobah],Footnote3 David took a vast quantity of bronze; with it Solomon made the bronze sea and the pillars and the vessels of bronze.” However historically reliable or otherwise Chronicles is, its authors seem unaware of any tradition of “King Solomon's Mines” even in the fourth or third century BCE when it was written.

The documentary producers, whatever their faults, realise all this, and perhaps even point us in the right direction:

King Solomon's mines were never mentioned in the Bible, but over the centuries became the stuff of legend, popularized by a 19th century adventure story and no less than three Hollywood movies.

The adventure story has its roots in the ruins of the 11th-14th century city of Zimbabwe, already mentioned in the sixteenth century, but not explored until the nineteenth, when there was great reluctance to allow that they were built by black Africans. Encouraged by Cecil Rhodes, the amateur archaeologist James Theodore Bent introduced the ruins to English readers, suggesting either Phoenicians or Arabs as builders.Footnote4 The German Karl Mauch, however, proposed that the buildings were meant as replicas of the Queen of Sheba's palace in Jerusalem,Footnote5 a fancy that appears to have provoked widespread discussion about a Solomonic connection: was this the place to which Solomon had sent his ships for precious metals and stones?

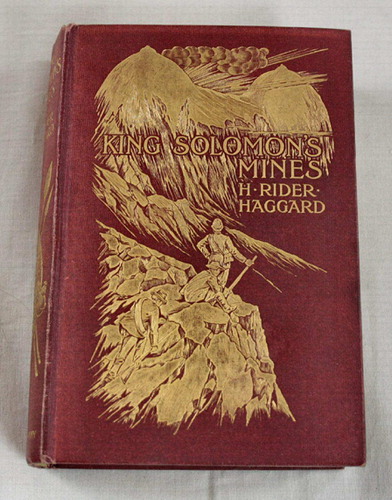

These ruins inspired the famous work of H. Rider Haggard, King Solomon's Mines, published in 1885. But the mines in this book yielded not copper but diamonds, and before we arrive definitively at copper or at mines, we have to consider a third commodity: gold. The search for Ophir, from whence Solomon is said to have acquired his gold, has a greater antiquity. As with Zimbabwe, the quest for Ophir does not involve Solomon in mining activity, but in long-distance trade. Zimbabwe itself was one candidate for the identity of Ophir, perhaps by Milton in Paradise Lost (11:399-401); another was Sofala in Mozambique, another Nejo in Ethiopia.

The crystallisation of all this legend into Solomonic copper-mining activity appears to have been the work of Nelson Glueck, who attributed the copper mining at Timna, 25 km north of Eilat, to King Solomon and named the site “King Solomon's Mines”. A series of natural structures formed by water erosion into pillar-shaped structures he dubbed, “King Solomon's Pillars” In the 1950s onwards onwards, Beno Rothenberg (who died exactly a year ago from the date of writing) who had followed up Glueck's discovery, unearthed a huge cluster of copper mines, smelting sites with furnaces, rock drawings, altars and temples, jewellery, and other artifacts. But to the huge disappointment of many, he established that these installations had no connection with Solomon, as well as reminding everyone that there was no biblical pretext for any Solomonic mining.

But the legend has survived and is now looking for another site at which to embody itself. It is fascinating to examine the ways in which history becomes legend, and biblical scholars have plenty of scope for such studies. But we also have to reckon with the art of the documentary makers, encouraged and abetted by certain archaeologists, who reverse this process and try to turn legends into history, in this case a history that the Bible itself does not support. But the true history of the tradition is actually rather more interesting and perhaps would have made a better documentary.

Notes

2 This character, Ḥiram (Kings) or Ḥuram (Chronicles) is not to be confused with the Tyrian king of the same name(s) who sold Solomon the wood and supplied the builders. The artisan's mother was from the tribe of Naphtali (Kings) or Dan (Chronicles). The Ḥuram of 2 Chron 2:13 is the character identified as the Masonic Master Hiram Abif.

3 Zobah's exact location is unknown, but it is commonly identified with subiti in Assyrian records. The biblical and Akkadian references all point to Syria.

4 James Theodore Bent and Robert McNair Wilson Swan, The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland: being a Record of Excavation and Exploration in 1891, London: Longmans Green, 1982.

5 Reported in “Vast Ruins in South Africa: The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland”, in the New York Times of 18th December 1892, p. 19.