Abstract

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are currently the first line treatment for chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in countries with high and intermediate-high gross national income. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) in these countries is considered salvage therapy for eligible patients who failed TKI or progress to advanced disease stages. In Latin America, treatment for CML also changed with availability of TKI in the region. However, many challenges remain, as the cost of this class of medication and recommended monitoring is high. CML treatment practices in Latin America demonstrate that the majority of patients are treated with TKI at some point after diagnosis, most commonly imatinib mesylate, but still TKI can only be used after interferon failure in some countries. Other treatment practices are different from established international guidelines, outlying the importance of continuing medical education. Allogeneic HCT is a treatment option for CML in this region and could be considered a cost-effective approach in a small subset of young patients with available donors, as the overall cost of long-term non-transplant treatment may surpass the cost of transplantation. However, there are many challenges with HCT in Latin America such as access to experienced transplant centers, donor availability, and cost of essential drugs used after transplant, which further impacts expansion of this treatment approach in patients in need. In conclusion, Latin American patients with CML have access to state of the art CML treatment. Yet, drug costs have a tremendous impact on developing health systems. Optimization of CML treatment in the region with appropriate monitoring, recognizing patients who would be transplant candidates, and expanding access to transplantation for eligible patients may curtail these costs and further improve patient care.

Keywords:

Introduction

Treatment for chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) changed significantly in the last 15 years. The advent of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) and its impact on the natural history of CML is among the great achievements of modern medicine and the flagship for effective targeted cancer therapy. TKIs are now the first line of treatment for CML; however, availability and cost of this class of medication limits its widespread use to patients worldwide. The World CML Registry reported that despite that 81% of patients worldwide received imatinib mesylate early in the course of the disease, hydroxyurea remains the first line of therapy outside the US and Europe.Citation1 Additionally, utilization of newer class of TKIs, which are more costly, is infrequent in many countries. Programs, such as Glivec International Patient Assistant Program sponsored by Novartis Pharmaceutics and managed by The Max Foundation assist in expanding access to TKI. In some countries in Latin America, distribution of TKI is provided by the government free of charge and the cumulative drug costs represent a real challenge for developing health systems.

Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for CML is the only proven curative therapy for CML. Despite high remission rates and low toxicity of TKIs compared to transplantation, many patients experience disease relapse upon discontinuation of these drugs. Mahon et al. discontinued imatinib mesylate in patients who were treated more than 2 years and who achieved complete molecular responses. The majority of patients experienced molecular relapse within 6 months from discontinuation of therapy.Citation2 Prior to the TKI era, CML was the most common indication for allogeneic HCT worldwide. Currently, CML is only considered for transplantation in patients who failed TKI or progress to advance stages of CML. Similarly, in Latin America allogeneic HCT for CML is no longer a common indication. This report overviews the treatment of CML in Latin America in the post-TKI era, its impact on transplant activity in the region, and patterns of care for this disease. Data reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplantation (CIBMTR) on transplant for CML were used in this report.Citation3

Activity of Transplants for CML

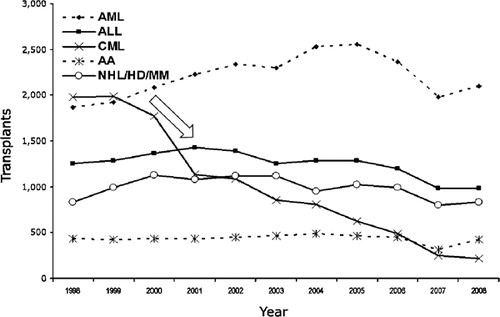

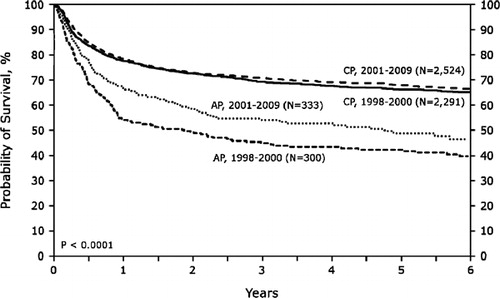

The impact of TKI is most obviously seen in the annual number of transplants reported to the CIBMTR worldwide, with a significant and steady drop starting in 1999 (). In the US and Canada, the annual number of allogeneic HCT for CML was in the range of 850–900 per year in 1998 and dropped to 200 per year in 2009. The CIBMTR has data on 5759 and 6258 transplant recipients with CML worldwide from the period of 1998–2000 and 2001–2009, respectively. It is noteworthy that in the later period, there is a higher proportion of patients in second chronic, accelerated, and blastic phases. Also, the use of mobilized peripheral blood increased from 30 to 38%, unrelated donors increased from 36 to 40%, and reduced intensity conditioning increased from 5 to 17% of transplants for CML in the later period. Other patient-related characteristics were similar between the two periods. Khoury and colleagues analyzed transplant outcomes for advanced CML from 1999 to 2004 and demonstrated that outcomes in these patients remain poor despite the availability of TKI.Citation4 Similar to others, this CIBMTR study did not demonstrate any impact on prior exposure to imatinib mesylate on post-transplant outcomes. Comparing overall survival after transplants for CML in the US from the period of 1998–2000 and 2001–2009 (2011 CIBMTR Summary Slides: www.cibmtr.org), the outcomes are similar for patients in CML chronic phase, but survival of patients in accelerated phase CML appears to be better in a later period (). This suggests that outcomes for at least accelerated phase CML are improving in the TKI era.

Figure 1. Annual number of hematopoietic cell transplantation for severe aplastic anemia (AA), acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), and lymphoproliferative diseases (NHL/HD/MM) reported to the CIBMTR from centers worldwide from 1998 to 2008.

Figure 2. Overall survival of recipients of human leukocyte antigen-matched sibling transplant for chronic myelogenous leukemia in the US and Canada by disease status at time of transplant and period pre-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) (1998–2000) and post-TKI (2001–2009). (2011 CIBMTR Summary Slides: wwww.cibmtr.org).

CML Treatment Practices in Latin America

TKI became available in Latin America in late 2000 through the expanded access program sponsored by a pharmaceutical company. Subsequently, after approval of imatinib mesylate for treatment of CML by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2001, drug distribution became commercially available. In many Latin American countries initially, imatinib mesylate was only approved as second line therapy after interferon failure. Currently in Brazil, imatinib mesylate at the dose of 400 mg/day is approved as first line therapy and it is provided free of charge to patients. Higher doses of imatinib mesylate and second generation TKIs are not covered to be used as first line, but they are commercially available. This practice varies in different countries, and generic and cheaper versions of imatinib mesylate are also available in some countries. The Max Foundation, partnered with Novartis Pharmaceutics, manages the Glivec International Patient Assistant Program and provides imatinib mesylate free of charge to eligible patients from developing countries (www.themaxfoundation.org). Furthermore, several patients from Latin America participated in international clinical trials of TKIs, which was a major contribution for timely completion of these important trials and expanded the access of these medications to patients in the region.Citation5Citation5,6

Use of TKIs in Latin America

The Latin American Leukemia Net ran a survey to study treatment practices for CML in 16 countries in the region.Citation7 A total of 435 disease specialists, mainly outside academic centers, participated in the survey providing a snap shot of real practice. Among the responders, 82% reported that imatinib mesylate was approved as first line therapy in their countries and only 7% reported that this drug was restricted to second line therapy. Second generation TKIs were available to 42% of responders. The breakdown of imatinib mesylate coverage was: 66% provided by the state, 18% insurance, 10% organizations or charity, and 5% was self-paid. Clinical scenarios addressing initial treatment options demonstrated that imatinib mesylate at the dose of 400 mg/day was the preferred treatment, irrespective of patient age. In the scenario of a 20-year-old patient with available sibling donor, 20% of responders elected proceeding to HCT up front. Cytogenetic was the preferred method for routine disease monitoring after initiation of treatment reported by 72% of responders and reverse transcriptase quantitated polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) for BCR-abl transcripts was reported to be routinely performed in 59% of responders. Monitoring was most frequently performed in 6 months intervals (54% cytogenetics and 41% qPCR). Interestingly, 13% of responders stated that they never used qPCR for disease monitoring. The monitoring practices are disparate from international guidelines established by the European Leukemia NetCitation8 outlying the importance of continuing medical education for optimal use of this class of medication.

Allogeneic Transplantation for CML in Latin America

According to data reported to the CIBMTR, the number of transplants reported annually for treatment of CML was 150 in the 1998 and dropped to 20 transplants a year in 2009. The drop in transplant activity occurred, unsurprisingly, with implementation of the Expanded Access Program for distribution of imatinib mesylate in the region in 2000. The CIBMTR accumulated data from 981 transplant recipients with CML in Latin America from 1998 to 2009. The median age of patients is 35 years, compared to 41 years in the US and Canada. It is noteworthy that 61% of transplants for CML in Latin America use bone marrow grafts and 86% use human leukocyte antigen-matched sibling donors. Only 9% of transplants for CML are from unrelated donors during the period. Among 658 patients in chronic phase who received sibling donor grafts in Latin America, the probabilities of 1 and 3 years overall survival were 68% [95% confidence interval (CI), 64–71%] and 59% (95% CI, 55–63%), respectively. Corresponding probabilities of 1693 patients in the US and Canada were 81% (95% CI, 79–83%; P<0·001) and 71% (95% CI, 68–73%; P<0·001), respectively. Among patients in accelerated phase CML, there were no significant differences in overall survival between regions. It is estimated that the CIBMTR captures approximately 70% of transplant activity in Latin America. For a region of close to 600 million in population, the number of transplant and transplant centers is very small, which impacts on access to transplantation for eligible patients. Another hurdle for transplantation in Latin America is donor availability as the majority of transplants use sibling donors, which are available at most in 35% of patients. The rising costs of treatment for CML with novel TKIs and requirement of frequent monitoring approach costs of an allogeneic transplantation. Cost-effectiveness analysis comparing transplants to TKIs for CML is difficult to interpret because of variability of costs of medication, medical care, monitoring, and transplantation in different countries compounded by the variability of complications according to transplant and donor type. One Mexican study compared the treatment of imatinib with nonmyeloablative conditioning transplant and demonstrated that the cost in the first 100 days post-transplant is equivalent to 180 days of imatinib in that country.Citation9 Another important point is comparative effectiveness of both treatments, one with curative potential but high risk of transplant-related mortality and the other with minimal mortality risk but costly with long term use. Bittencourt and colleagues retrospectively compared the outcome of 174 imatinib recipients after interferon failure to 90 transplant recipients from three Brazilian centers.Citation10 Transplant recipients were younger than the non-transplant cohort. The 5-year event-free survivals were 62 and 52% (P<0·002) for the imatinib mesylate and transplant cohorts, respectively. Corresponding probabilities for overall survival were 93 and 59% (P<0·001), respectively. These results should be interpreted with caution, as the decision to receive a particular treatment was according to institutional guidelines with possible selection bias and the transplant cohort combined sibling and unrelated donor recipients. One important consideration is that, depending on the clinical scenario, transplantation might be a better overall long-term treatment option.

Conclusions

Treatment for CML in Latin America has evolved in parallel to other regions. Drug distribution programs by governments in many countries allowed access to this medication to majority of patients. International assist programs for eligible patients also contributed to expanded access of this medication to patients. Yet, as survival of patients with CML is prolonged by effective treatment and the incidence remains the same, the cumulative effect on cost of treating these patients will further impact the constrained resources in developing health systems. Availability of generic TKI versions throughout Latin America, besides the legal patent issues, needs to be addressed in respect of activity compared to non-generic drugs and regulated with the same rigor as non-generic compounds. Proper monitoring with TKI is also an important aspect of treatment, which can avoid waste of expensive drug in patients who are not optimally responding.

CML is an infrequent HCT indication, but there is still a role in certain situations. Appropriate cost-effectiveness analysis that accounts subset of patients and scenarios is needed especially in the context of constrained resources. Additionally, CML is the most sensitive malignancy to graft-versus-leukemia effect which can induce cure. Early identification of patients who are poor risk for disease relapse, patients who acquire TKI-resistant mutations, or patients with suboptimal response with second generation TKIs should be considered for transplantation.

References

- Pasquini R, Cortes JE, Kantarjian HM, Joske D, Meillon LA, Zernovak O, et al.. Survey of the frontline treatment and management of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in a real-word setting: the 3rd annual update of the worldwide observational registry collecting longitudinal data on management of chronic myeloid leukemia patients (The WORLD CML Registry). Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). 2011;118(21):Abstract 1695.

- Mahon F-X, Réa D, Guilhot J, Guilhot F, Huguet F, Nicolini F, et al.. Discontinuation of imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia who have maintained complete molecular remission for at least 2 years: the prospective, multicentre Stop Imatinib (STIM) trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(11):1029–35.

- Pasquini MC, Wang Z, Horowitz M, Gale RP. 2010 report from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR): current uses and outcomes of hematopoietic cell transplant for blood and bone marrow disorders. In: , Cecka J M, Terazaki P I, ed, editors. Clinical transplants 2010. Los Angeles (CA): The Terasaki Foundation Laboratory; 2011. p. 87–105.

- Khoury HJ, Kukreja M, Goldman JM, Wang T, Halter J, Arora M, et al.. Prognostic factors for outcomes in allogeneic transplantation for CML in the imatinib era: a CIBMTR analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011.

- Kantarjian H, Shah NP, Hochhaus A, Cortes J, Shah S, Ayala M, et al.. Dasatinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2260–70.

- Saglio G, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S, le Coutre P, Etienne G, Lobo C, et al.. Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2251–9.

- Cortes J, De Souza C, Ayala-Sanchez M, Bendit I, Best-Aguilera C, Enrico A, et al.. Current patient management of chronic myeloid leukemia in Latin America: a study by the Latin American Leukemia Net (LALNET). Cancer. 2011;116(21):4991–5000.

- Baccarani M, Saglio G, Goldman J, Hochhaus A, Simonsson B, Appelbaum F, et al.. Evolving concepts in the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2006;108(6):1809–20.

- Ruiz-Arguelles GJ, Tarin-Arzaga LC, Gonzalez-Carrillo ML, Gutierrez-Riveroll KI, Rangel-Malo R, Gutierrez-Aguirre CH, et al.. Therapeutic choices in patients with Ph-positive CML living in Mexico in the tyrosine kinase inhibitor era: SCT or TKIs? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42(1):23–8.

- Bittencourt H, Funke V, Fogliatto L, Magalhaes S, Setubal D, Paz A, et al.. Imatinibmesylate versus allogeneic BMT for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in first chronic phase. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42(9):597–600.