Abstract

This update will focus on new developments which can impact the understanding and management of patients with DLCL. The latter disorder is mostly derived from B lymphocytes which can be further subdivided into those that originate from the germinal center versus those that arise from non-germinal center areas in the lymph node. The differences between these two types will be discussed. The management of several new entities that relate to DLCL such as ‘double hit lymphoma’ and so called borderline entities will also be featured. New entities such as breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma will be described.

During the past decade, we have witnessed a number of changes in the field of NHL, including new entities added to the classification as well as a better understanding of the biology of diffuse large cell B (DLBCL) cell. It has become increasingly clear that DLBCL is a biologically and clinically heterogeneous group of disorders. With the use of gene profiling, two major molecular categories are now recognized: germinal center B-cell (GCB) and activated B-cell (ABC) types. The former is associated with a good prognosis while the latter is known to have a more adverse outcome. With the application of routine immunohistochemical stains, these two types can be identified using the Han’s algorithm which has an 80% concordance with the results of gene profiling. The ABC type appears to be derived from plasmablasts and is known to be nuclear factor Kappa B (NF-Kappa B) dependent, analogous to plasma cells in myeloma. NF-kappaB is a therapeutic target for Bortezomib and for that reason is being investigated as treatment for this subtype of DLBCL.

Several major changes in the classification will be discussed among which the most important are the recognition of so called ‘borderline entities’. The first borderline category includes the entity formally known as B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable with features intermediate between DLBCL and classical Hodgkin. This entity is also known as Mediastinal Gray Zone NHL (MGZL). It has pathological features that are intermediate between primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) and nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma (NSHL). All three entities are presumed to be derived from thymic B cells.

B-cell Lymphoma, Unclassifiable with Features Intermediate between DLBCL and Classical Hodgkin (Mediastinal Gray Zone NHL)

Primary mediastinal B-cell NHL, MGZL and HDNS significantly overlap molecularly according to gene profiling studies, as well as clinically. Perhaps the overlapping features seen in MGZL should not surprise us given the fact that primary mediastinal large cell NHL has a molecular gene profile almost identical to classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Clinically they are characterized by young age and localized mediastinal presentation. The histologic features of MGZL can include pathological aspects intermediate between PMBL and NSHL or could be limited to immunophenotypical features atypical for NSHL (ex. CD20+ or CD15−/CD30+ or CD15+/CD30−). A tumor with histological features typical of NSHL can be considered as consistent with MGZL just based on atypical immunohistochemical characteristics.

Literature reports suggest that MGZL has a relatively poor prognosis when treated with Hodgkin-based chemotherapy. Anecdotal reports suggest that MGZL is relatively resistant to Hodgkin-based chemotherapy. Only 35% of these cases are cured with front line therapy directed at Hodgkin lymphoma. New treatment approaches are necessary. Incorporation of new agents such as Brentuximab into front line therapy for this disorder should be explored.

B-cell Lymphoma, Unclassifiable with Features Intermediate between Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma and Burkitt Lymphoma or DLBCL/Burkitt Lymphoma (‘DLBCL/BL’)

Another borderline entity or gray zone lymphoma is the DLBCL/Burkitt lymphoma (‘DLBCL/BL’) which has features of both DLBCL and Burkitt’s lymphoma. The overlapping features might consist exclusively of atypical morphological characteristics or immunohistochemical features. For example the cells might be slightly larger than expected for BL or bcl-2 is expressed which is not compatible with BL.

Many cases in this DLBCL/BL category contain a translocation of MYC such as t(8;14) and 60% also carry a coexistent BCL2 translocation such as t(14;18), so-called ‘double-hit lymphomas’ which have a very aggressive clinical behavior. The activation of the myc oncogene results in a markedly increased proliferative rate characterized by a high Ki-67 fraction. At the same time they overexpress the antiapoptotic bcl-2 gene. The net result is an exceptionally high cellular proliferation simultaneously with a lack of apoptosis. Most of these cases when treated with Burkitt-based chemotherapy regimens, will die within 1 year. In view of their dismal prognosis some centers are using either upfront autologous or allogeneic transplantation for their management. Anecdotal experience suggests that this approach improves their prognosis.

Not only have the double hit lymphomas been identified as adverse in their prognosis but also the presence of t(14;18) has very recently been shown to carry a negative connotation in regard to its prognosis when present in cases of DLBCL.

Breast Implant Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

Recently the FDA identified a possible association between breast implants and the development of anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). These tumors develop adjacent or in close contact to the breast implant thus suggesting cause–effect. The risk of women with breast implants developing ALCL is very low but in reference to the general population, it appears increased. A literature review identified 34 cases of ALCL in women with breast implants worldwide but the FDA has identified additional cases for a total of approximately 60 cases. These additional cases were identified through other international regulatory agencies, scientific experts and breast implant manufacturers. Considering that there are 5–10 million women who have received breast implants worldwide, this would represent 60 out of 5–10 million for an estimated incidence of reported cases ranging from 0·0006 to 0·0012% or 0·6 to 1·2 out of every 100 000 patients with breast implants. However, this is probably an underestimate because: (1) not all cases are reported; and (2) some clinicians might fail to recognize the disease as breast implant related ALCL.

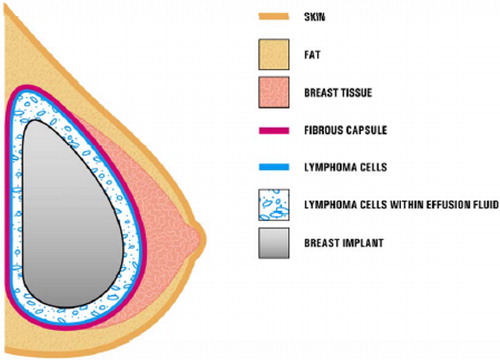

The typical clinical presentation consists of a patient with late onset, persistent peri-implant seroma (). In some cases, patients present with capsular contracture or masses adjacent to the breast implant. In such cases it is recommended that the seroma fluid be collected and tested for ALCL with Wright Giemsa stained smears and cell block. Immunohistochemistry for CD-30 and anaplastic lymphoma kinase markers should be carried out.

Figure 1. Presence of ALCL cells in close proximity to a breast implant. In most cases, the ALCL cells were found in the effusion fluid (seroma) surrounding the implant or contained within the fibrous capsule. (Reproduced from http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/BreastImplants/ucm239995.htm).

It is unclear whether this disorder is more commonly associated with the silicone type of implant versus the saline type. However, the outer shell of saline implants is made of silicone which suggests that this material might be the etiologic agent involved in the pathogenesis. It is not clear how many women worldwide have silicone vs saline implants. This makes it impossible to figure out the incidence of ALCL associated with each of these two types of implants. However, from 1992 to 2006 silicone implants were partially banned in the USA and 90 to 95% of the implants performed during that period were saline-filled. In Europe and South America, no such ban was implemented. shows that most of the cases of ALCL were associated with silicone type implants.

Table 1. Characteristics of 34 published cases of ALCL in women with breast implants

Immunological Subtypes

With the advent of gene profiling, it has become increasingly clear that DLBCL is a biologically and clinically heterogeneous disorder. Two major categories are now recognized: GCB and ABC types. A third type of DLBCL, primary mediastinal large cell lymphoma shows a genetic profile almost identical to Hodgkin disease. The GCB type is associated with a good prognosis while the ABC type is known to have a more adverse outcome.1 With the use of routine immunohistochemical stains, these two types can be identified most of the time. The GCB type is CD10+, bcl-6+, or may be CD10−, bcl-6+ but MUM1–, while the ABC type is CD10−, bcl-6− or CD10−, bcl-6+ but MUM1 positive. These data not only have prognostic implications but more important than that is that the ABC type is known to be dependent on NF-kappaB. Bortezomib is a first generation proteosome inhibitor which inhibits NF-kappaB, thus NF-kappaB appears to be an excellent therapeutic target for this drug which is actively being investigated as treatment for the ABC type. Mantle cell NHL is also known to be associated with dysregulation and over expression of NF-kappaB; treatment with Bortezomib has been very successful in that disorder.

Conclusions

Knowledge gained from the basic biology of lymphomas can provide important insights which can be relevant to better refine and improve the treatment for these disorders. As we gather further information about these disorders new therapeutic targets will likely emerge.

Reference

- Rosenwald A, Staudt LM. Gene expression profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44(Suppl 3):S41–7.