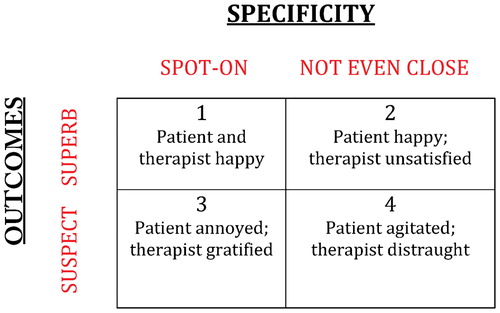

I have watched the debate over specificity of manual techniques for many years. From the vantage of the practitioner and patient, the contingency table below portrays the clinical interplay in the moments following a thrust technique. Admittedly, there are shades of gray between these cells, but they largely represent what the segment-specific trained manual therapist and his/her patient experience when a manipulation is applied. I am one of those manual therapists and I have experienced the feeling associated with each of the four cells in my years of practice. What is the basis for this swing of emotion related to outcomes? In all of our Clinical Prediction Rules do we ever consider what is going on in the practitioner’s mind and how this might influence his/her clinical decision-making? Are there important considerations herein for the didactic preparation of manual therapists?

No matter what form of intervention we employ in our business, when the clinical decision for the intervention (manipulation or otherwise) was ‘spot-on’ and the patient is happy, there is no question that the feeling is splendid; it is why we went into the business of manual therapy. The feeling brings a fulfilling sense of accomplishment and a reward of instant gratification, almost a ‘clinical high’. We have all been there at one time or another in our practice. It fulfills our desire to be good at what we do and to help others. It’s a great place to be at the end of a smartly performed manipulation. If you’ve taken time to be very deliberate in your set up and to extract a single, audible cavitation from the targeted segment, then the reward seems magnified somehow. There are no consequences other than good ones. Or, are there?

To a manual therapist immersed in the holy waters of specificity, there is marginalized satisfaction in cell #2. Okay, I understand that, at the end of the day, the important consideration is whether or not our patient benefitted as a result of our intervention. Don’t get me wrong; I am still ‘good’ with that. But, there is a little bit of the emotion left out there on the playing field. I liken it to the feeling that a professional baseball player must feel when he watches his team win the game, but he went 0 for 4 at the plate. There is an ‘emptiness’ in your gut; the feeling that the team won in spite of you- not because of you. It is not as if you did not contribute to the win; it’s more that the outcome was serendipitous rather than a consequence of your impeccable training and aptitude for hitting a baseball. However, given that our patient is, at least for the moment, pleased with the results of your intervention, you take the credit and move on, determined, perhaps, to do better next time. The consequence of this scenario is not always predictable. As noted by Flynn et al,Citation1 there is evidence to show that practitioners gauge the success of their manipulation, at least, by an audible pop. If you are segment-specific trained, you want that cavitation right at the targeted segment. Might one be persuaded to try again to affect that, even though the patient’s response might not dictate that action? Herzog et alCitation2 suggest that that is exactly the case.

There is overt dismay in cell #4. That is automatic. None of us wanted this when we started our journey to become a manual therapist. Not only was our set-up suspect, in all likelihood because, otherwise, how could we have ‘missed’? But the consequence went beyond ‘doing no harm’. At least for the moment (and hopefully no longer), our patient is worse and our feelings run amuck. Our thoughts might run the gamut of blaming the patient for not relaxing (among other possibilities) to ‘kicking our self’ for poor performance. The consequence of either is not very constructive; perhaps harmful.

Cell #3? Now there is a complex feeling for the manual therapist. Have you been there? When you have been segment-specific trained with your manipulative techniques, there is something of a placebo FOR THE THERAPIST that comes out of this scenario. But, the patient is left in the lurch. He/she does not feel better, but maybe ‘trusts’ that you did the right thing since the sound of the cavitation was also readily perceived by the receiver. Given the proclivity for successful, segment-specific manipulative thrusts, one might be inclined to go down the decision-making road of convincing him/herself that ‘just one more’ thrust, as competently delivered as the former, will do the trick and bring about success, as defined now by the patient’s perception of reduced pain. Emotion might displace reasoning- especially, perhaps, for a new manual therapist. Are there consequences?

What is behind the Editor’s rambling here? Is he sacrificing the sacred cow of specific manipulation, as described a number of years ago by Miller?Citation3 Hardly. With all due respect to the proponents of non-specific manipulations and the literature that supports that, I am forever grateful for the instruction that taught me, if nothing else, to be meticulous in my patient handling skills. I am just trying to offer a perspective on teaching spinal manipulation that might be overlooked.

I suggest that each of the scenarios above, broadly defined by the cells in the contingency table, will provoke an intrinsic response in the practitioner. Even cell #1 has potentially confounding consequences. Upon the patient’s return, in a fast-paced clinic, the therapist can easily be drawn into a ‘repeat performance’ for the sake of efficiency and gratification. When you have been specific-segment trained (at least; I can’t speak to non-specific instruction), scenarios depicted by any of the cells can seduce the practitioner to try again, for the sake of practice, if nothing else. After all, the skill is acquired and perhaps maintained through a suitable number of repetitions on a daily basis. You cannot let too many days go by without ‘taking your swings’.

The message here is probably most suited to those just stepping over the threshold of independent practice of these skills, as well as to those who teach them. Successfully isolating a technique to a targeted segment can produce a ‘high’ for the patient and the practitioner. However, we must be careful to guard against the unwarranted euphoria that can be consequent to the ‘addiction’ that can occur from momentary satisfaction of spot-on manipulations. Should we then set aside that specificity of training for something less technically difficult? I don’t think so. I do offer that we should discuss the consequences of these emotions with those we train so that optimal decision-making is not sacrificed for the sake of personal gratification and/or the yearning for an immediate response. If we are not careful, I think that we’re at risk for either every time we see a patient. Emotion and determination must not trump clinical reasoning when it comes to spinal manipulation.

References

- Flynn TW, Childs JD, Fritz JM. The audible pop from high-velocity thrust manipulation and outcome in individuals with low back pain. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2006;29(1):40–45.

- Herzog W, Shang YT, Conway PJ, Kawchuk GN. Cavitation sounds during spinal manipulative treatments. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1993;16(8):523–526.

- Miller J. Letter to the editor. J Man Manip Ther 2007;15(2):123–124.