Abstract

Partly because of a potential graft-versus-myeloma effect, allogeneic stem cell transplantation is a potentially curative treatment modality in patients with multiple myeloma (MM). Initial attempts have been hampered by the high transplant-related mortality in this setting. With a reduction of toxicity, allogeneic transplant approaches with reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) have been utilized, although they are subjected to continued disease progression and relapse following transplantation. We analyze here the experience of allografting four patients with MM in a single institution, along a 16-year period in which a total of 152 individuals were allografted, using an RIC regimen; three of the patients have had previous autografts. All patients engrafted successfully and a graft-versus-myeloma effect was shown in all of them. One patient relapsed in the face of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Three patients have died (two as a result of GVHD) and one is alive with a limited form of chronic GVHD. The graft-versus-myeloma effect can be induced by means of allogeneic transplantation but the morbidity and mortality associated with the procedure leads into a relatively small proportion of MM patients being cured.

In multiple myeloma (MM), high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) remains an integral component of upfront treatment strategy,Citation1,Citation2 and the incorporation of novel immunomodulators and proteasome inhibitor into induction regimens improves response rates and increases overall survival (OS). Bortezomib- and lenalidomide-based combination chemotherapy regimens have become the standard induction myeloma therapy. When MM patients proceed to transplant after novel combination regimens, their response rates are further improved. Despite these recent major improvements, MM remains incurable and long-term survival seems elusive.

Partly because of a potential graft-versus-myeloma effect, allogeneic HSCT is a potentially curative transplant option in MM.Citation3,Citation4 However, initial attempts have been hampered by the high transplant-related mortality in this setting. With a reduction of toxicity, allogeneic transplant approaches with reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) have been utilized, although they are subjected to continued disease progression and relapse following transplantation.Citation4 RIC allogeneic HSCT can result in reliable donor engraftment, relatively low treatment-related mortality, and sustained remissions in the treatment of MM.Citation5 However, substantial cytoreduction pre-allografting is often necessary because of a variable graft-versus-myeloma effect. Unfortunately, similar to autografting, relapse remains the major cause of treatment failure after RIC allogeneic HSCT. To improve treatment results with allografting, consideration should be given to incorporating immunomodulatory drugs and targeted treatments to enhance pre-transplantation remission status, as post-transplantation maintenance therapy, or in combination with donor lymphocyte infusions for refractory or relapsed disease.Citation5

We analyze here the experience of allografting patients with MM in a single institution, along a 16-year period in which a total of 152 individuals where allografted.

Material and methods

Patients

Data were analyzed from all MM patients who underwent HSCT using the Mexican RIC scheduleCitation6 in the Centro de Hematología y Medicina Interna de Puebla of the Clinica Ruiz between March 1996 and June 2012. The study was approved by the ethics commmitte of the Clinica Ruiz. MM patients were allografted after relapsing from a previous autograft, except in one case (number 4) in which the indication was a refractory disease in a young individual (39 years old) with deletion 13 ().

Allo-HSCT

The ‘Mexican method’ of RIC was used in all patients.Citation6 A Karnofsky score of 100% was required to conduct the allograft. In all instances, the donor was a sibling with compatible (5/6) or identical (6/6) human leukocyte antigen. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee of the institution. Written consent was obtained from all patients. Subcutaneous granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor (10 µg/kg/day) was given to the sibling donors on days −5 to +2, and one to three aphaeresis procedures were planned for days 0, +1, and +2 by means of a Haemonetics V-50 PLUS machine (Haemonetics Corporation, Braintree, MA, USA), a Baxter C-3000 PLUS machine (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL, USA), an AMICUS (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL, USA), or a COBE-Spectra (Gambro, Lakewood, CO, USA) using the Spin-Nebraska protocol.Citation6 The endpoint of collection was the processing of 5000–7000 ml of blood/m2 in each aphaeresis procedure, providing a total amount of at least 2 × 106 viable CD34+ cells/kg of the weight of the recipient. The Mexican method of non-ablative conditioning used in this study consisted of the followingCitation6: oral busulfan, 4 mg/kg, given on days −6 and −5; intravenous (I.V.) cyclophosphamide, 350 mg/m2, on days −4, −3 and −2; and IV fludarabine, 30 mg/m2, on days −4, −3 and −2; oral cyclosporin A (CyA) was administered at 5 mg/kg starting on day –1. In all the patients IV methotrexate (5 mg/m2) was given on days +1, +3, +5, and +11. CyA was continued through day 180, with adjustments made to obtain serum CyA levels of 150–275 ng/ml, and then tapered over 30–60 days. If graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) was present, CyA was tapered over a longer period. Ondansetron (1 mg IV every hour for 4 h after I.V. chemotherapy), an oral quinolone, and an azole were used in all patients until granulocyte counts were greater than 500 × 106/l for three consecutive days. The peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) aphaeresis products were infused on days 0 to +1. The total counts of white blood cells, mononuclear cells, and CD34+ cells were enumerated by the flow cytometryCitation7 with an EPICS Elite ESP machine (Coulter Electronics, Hialeah, FL, USA), using the anti-CD34 monoclonal antibody HPCA-2 (Becton Dickinson, San José, CA, USA). No purging procedures were performed. Engraftment was defined as an absolute neutrophil count of >0.5 × 109/l for at least three consecutive days, and platelet engraftment was defined as occurring on the first of seven consecutive days with a platelet count of >20 × 109/l, without a platelet transfusion. Graft failure was defined as the failure to reach an absolute granulocyte count of >0.5 × 109/l on day +30. Chimerism was assessed in cases involving a sex mismatch with a fluorescent in situ hybridization technique to mark the X and Y chromosomes.Citation8 In cases with an ABO mismatch, a flow cytometry-based approach was used, whereas polymorphic markers (short tandem repeats)Citation9 were analyzed in the absence of any mismatch. After the allograft, no anti-myeloma treatment was delivered to the patients.

Statistics

The primary objective of the analysis was to assess the survival after the HSCT. OS was calculated from the day of HSCT until the day of death or the last follow-up and was estimated according to the Kaplan–Meier methodCitation10 using the log-rank chi-square test.

Criteria for response

The criteria for response were the following: complete remission was defined as the absence of paraprotein on serum electrophoresis and 5% or fewer plasma cells in the marrow. Very good partial response was defined as a decrease of 90% in the serum paraprotein level. Partial remission as a decrease of 50% in the serum paraprotein level, and minimal response (MR) as a decrease of 25% in the serum paraprotein level.Citation1

Results

Patients

Between March 1996 and June 2012, a total of 152 patients received an allogeneic HSCT in the Centro de Hematología y Medicina Interna at the Clínica Ruiz (Puebla, México); 4 of them were MM patients; all of them with a Karnofsky performance index of 100% when the allograft was conducted. Details regarding age, gender, type of myeloma, chimerism, GVHD, current status, and survival are listed in . In this period, 41 MM patients were autografted.Citation1

Table 1. Salient features of the four MM patients allografted using a reduced-intensity preparative regimen

Allografts

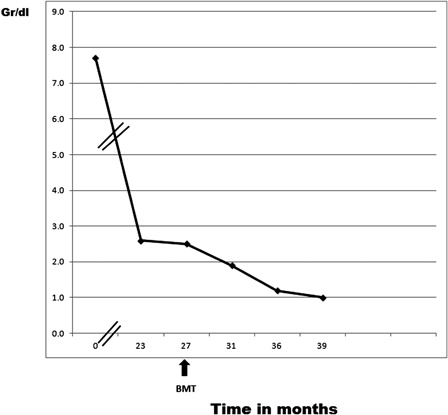

All patients received peripheral blood stem cells allografts. All of the grafts were 6/6 matches. Engraftment occurred in all patients. Chimerism studies were performed in all patients using the techniques previously described. Evidence of chimerism was found in all the allografted individuals. One patient (number 1) had a relapse of the myeloma, according to the amount of paraprotein which increased after having dropped following the allograft ().

Survival

In the whole group, the post-allograft 15-month OS was 25%, whereas the median OS was 9 months. The table shows the results of the allograft in the four patients. In all the cases, a graft-versus-myeloma effect was shown: There were two MRs and two partial responses. One patient relapsed after the allograft. Two patients died as a result of extensive GVHD, one patient died because of a cerebral aspergilloma, whereas one patient is alive 15 months after the allograft.

Discussion

MM is a life-threatening hematological malignancy for which standard therapy is inadequate. Autologous stem cell transplantation is a relatively effective treatment, but residual malignant sites may cause relapse. Allogeneic transplantation may result in durable responses due to antitumor immunity mediated by donor lymphocytes; however, morbidity and mortality related to GVHD remain a challenge. Recent advances in understanding the interaction between the immune system of the patient and the malignant cells are influencing the design of clinically more efficient study protocols for MM.Citation11

Allogeneic HSCT has developed into immunotherapy. Donor CD4+, CD8+, and natural killer cells have been reported to mediate graft-versus-malignancy (GVM) effects, using Fas-dependent killing and perforin degranulation to eradicate malignant cells. Cytokines, such as interleukin-2, interferon-gamma, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha potentiate the GVM effect. Post-transplant adoptive therapy of cytotoxic T-cells against malignancy-specific antigens, minor histocompatibility antigens, or T-cell receptor genes may constitute successful approaches to induce anti-tumor effects. Clinically, a significant GVM effect is induced by chronic rather than acute GVHD. An anti-tumor effect has been reported for myeloma, leukemia, lymphoma, and solid tumors.Citation12 RIC enables HSCT in older and disabled patients and relies on the GVM effect. A high CD34+ cell dose of peripheral blood stem cells increases GVL and there is a balance between effective immunosuppression, low incidence of GVHD, and relapse. Unlike leukemia and lymphoproliferative disorders, allo-HSCT has yet to find its place in the clinical management of patients with MM. Allo-SCT in MM is associated with a high procedure-related mortality (up to 35%) when full-intensity conditioning is used and only up to 36% of cases show long-term disease-free survival;Citation13 the introduction of RIC allo-HSCT has reduced the transplant related mortality to <20%, but there is an associated increased relapse risk.Citation13

The four cases which we have presented here support the induction of a graft-versus-myeloma effect, since in all the cases, after the allograft, the amount of abnormal protein dropped without any further anti-myeloma treatment. The graft-versus-myeloma effect was coupled in two cases with extensive GVHD which was responsible for the death of two patients (1 and 2) and related to the death of the other one since the use of immunosuppression may have prompted the cerebral aspergillosis which ended the life of the patient number 3. The patient who is alive (number 4) is the youngest one and has tolerated relatively well both the chronic GVHD and its treatment.

In pursuit of the putative graft-versus-myeloma effect, we need to consider the whole patient management pathway both preceding (depth of response to novel agents) and post-allo-HSCT, to minimize the toxicity while harnessing the adoptive immunotherapy effect.

References

- López-Otero A, Ruiz-Delgado GJ, Ruiz-Argüelles GJ. A simplified method for stem cell autografting in multiple myeloma: a single institution experience. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44:715–9.

- Ruiz-Delgado GJ, Ruiz-Argüelles GJ. El trasplante autólogo sigue siendo importante en el tratamiento del mieloma múltiple. Rev Hematol Méx. 2011;12 (Suppl 1):S1–2.

- Nishihori T, Alsina M. Advances in the autologous and allogeneic transplantation strategies for multiple myeloma. Cancer Control. 2011;18:258–67.

- Nivison-Smith I, Dodds AJ, Doocey R, Ganly P, Gibson J, Ma DD, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant for multiple myeloma using reduced intensity conditioning therapy, 1998–2006: factors associated with improved survival outcome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52(9):1727–35.

- Salit RB, Bishop MR. Reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma: a concise review. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2011;11(3):247–52. Epub 2011 Apr 20.

- Ruiz-Delgado GJ, Ruiz-Argüelles GJ. A Mexican way to cope with stem cell transplantation. Hematology. 2012;17 (Suppl 1):195–7.

- Ruiz-Argüelles A, Orfao A. Caracterización y evaluación de células totipotenciales en sangre periférica y médula ósea. In: , Ruiz-Argüelles GJ, San-Miguel JF, (eds.) Actualización en Leucemias. México City: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 1996. p. 79–82.

- Pinkel D, Straume T, Gray JW. Cytogenetic analysis using quantitative, high sensitivity fluorescence hybridization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;83:2934–8.

- Yam PY, Petz LD, Knowlton RG, Wallare RB, Stock AD, de Lange G. Use of DNA restriction fragment length polymorphisms to document marrow engraftment and mixed hematopoietic chimerism following bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation. 1987;43:399–407.

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimations from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–63.

- Danylesko I, Beider K, Shimoni A, Nagler A. Novel strategies for immunotherapy in multiple myeloma: previous experience and future directions. Clin Rev Immunol. 2012;2012:753407. Epub 2012 May 10.

- Ringdén O, Karlsson H, Olsson R, Omazic B, Uhlin M. The allogeneic graft-versus-cancer effect. Br J Haematol. 2009;147(5):614–33. Epub 2009 Sep 4.

- Cook G, Bird JM, Marks DI. In pursuit of the allo-immune response in multiple myeloma: where do we go from here? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43(2):91–9. Epub 2008 Dec 15.