Abstract

The beneficial effect of rituximab for first-line treatment of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) has been demonstrated by several randomized controlled trials. To clarify whether results for selected patient populations also apply to unselected patients, we analyzed long-term outcomes for all the 277 consecutive adults diagnosed with de novo DLBCL in a single center between 1998 and 2008. The study population included 147 and 130 patients diagnosed before (Cohort A) and after the advent of rituximab (Cohort B). Progression-free survival (PFS) was significantly better for Cohort B than for Cohort A (P = 0.005). For patients age 60 or younger, PFS did not differ significantly between Cohort A and Cohort B (P = 0.329), but for patients over 60, Cohort B showed superior PFS (P = 0.002). Patients with high or high-intermediate risk according to the International Prognostic Index score showed less improvement in PFS than did those with low or low-intermediate risk primarily because of still unfavorable outcomes of patients with poor performance status. These results indicate that the advent of rituximab has significantly improved outcome for unselected patients with DLBCL, and that improvement was greater for older patients. Further investigations are warranted in the hope of improving outcomes for younger patients with DLBCL.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, accounting for approximately one-third of the disease in adults.Citation1,Citation2 Since the advent of rituximab, the treatment of DLBCL has been changed drastically, and rituximab combined with chemotherapy has become the current treatment of choice for newly diagnosed DLBCL.Citation1 This change in clinical practice occurred mainly based on results obtained in clinical trials which showed the survival advantage of adding rituximab to chemotherapy for previously untreated DLBCL patients.Citation3–Citation6 However, patients entered into clinical trials are always selected, and as is well known, they do not represent the general patient population.Citation7 For this reason, some investigators have attempted to evaluate the possible benefits of rituximab in retrospective case-control studies and population-based studies.Citation8–Citation14 Those studies were still limited, however, due to, for example, patient selection (i.e. including only patients treated intensively),Citation10–Citation14 lack of detailed information because of multicenter surveys,Citation9–Citation14 and relatively short follow-up.Citation8–Citation14 To further examine how the introduction of rituximab has changed the clinical course of DLBCL by overcoming these limitations, we analyzed long-term outcomes for all the 277 adult patients with de novo DLBCL diagnosed consecutively at our institution between 1998 and 2008.

Methods

Patients

All patients 18 years or older who had been newly diagnosed with DLBCL at the Fujita Health University Hospital between January 1998 and September 2008 were eligible for inclusion in this study. Only those with a previous history of any type of lymphoma were excluded. The diagnosis of DLBCL was based on the World Health Organization (WHO) classification,Citation15 and external expert hematopathologists from the Adult Lymphoma Treatment Study Group (ALTSG) reviewed and confirmed all of the diagnoses. As rituximab has been routinely used since January 2004 for the treatment of DLBCL at our institution, we classified the patients into two groups according to the time of diagnosis: Cohort A (January 1998 through December 2003) and Cohort B (January 2004 through September 2008). We did so instead of dividing patients by whether or not they actually had received rituximab for first-line treatment, because our aim was to evaluate how the advent of rituximab has impacted outcome of the overall patient population including those who were minimally treated and even those who were not treated at all. The whole study population comprised 277 patients, 147 in Cohort A and 130 in Cohort B. At presentation, patients were evaluated with respect to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, Ann Arbor clinical stage, number of extranodal sites, the International Prognostic Index (IPI) score,Citation16 the presence of B symptoms, and serum level of soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R). The sIL-2R level was considered as a dichotomous variable with a cut-off at 2000 IU/ml.Citation17,Citation18 This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fujita Health University School of Medicine.

Statistical analysis

Distributions of patient characteristics for the two groups were compared by using the Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. Overall survival (OS) was calculated as the time from diagnosis to death, and progression-free survival (PFS) as the time from diagnosis to progression or death.Citation19 Patients without an event were censored at last visit. A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to estimate the probabilities of OS and PFS, and differences between groups were compared by means of the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was constructed for multivariate analysis and hazard ratio (HR) was calculated together with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). All statistical analyses were performed by using Stata version 12.0 software (StataCorp. LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Patients

A total of 277 patients were eligible for analysis, including 160 male and 117 female patients with a median age of 65 years (range, 18–91 years). Baseline characteristics of the patients in Cohort A (N = 147) and Cohort B (N = 130) are presented in . There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups with respect to age, sex, LDH level, clinical stage, number of extranodal sites, and sIL-2R level. Patients in Cohort A were more likely to present with poor PS and B symptoms. According to the IPI score, the proportions of subjects at low, low-intermediate, high-intermediate, and high risk were 25, 20, 27, and 28% for Cohort A, and 31, 30, 22, and 18% for Cohort B, respectively.

Table 1. Patient characteristics

As initial therapy, 268 patients (97%) received anthracycline-based chemotherapy with or without rituximab. Rituximab was used for six patients (4%) in Cohort A and 111 patients (85%) in Cohort B. Nineteen patients in Cohort B did not receive rituximab as part of an initial therapy because of a carrier of the hepatitis B and/or C viruses (n = 6), having received no chemotherapy (n = 6), early death (n = 2), and miscellaneous reasons (n = 5). Overall, 38 patients (26%) in Cohort A and 115 patients (88%) in Cohort B were treated with rituximab during the entire observational period. Regardless of the use of rituximab, CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone)Citation20 was initially administered to 77 patients (52%) in Cohort A and to 98 patients (75%) in Cohort B, whereas CyclOBEAP, in which bleomycin and etoposide were added to the CHOP regimen,Citation21 to 69 patients (47%) in Cohort A and 23 patients (18%) in Cohort B. Sixteen patients (11%) in Cohort A and eight (6%) in Cohort B underwent hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), of whom five in Cohort A and two in Cohort B received HCT during first complete remission (CR1).

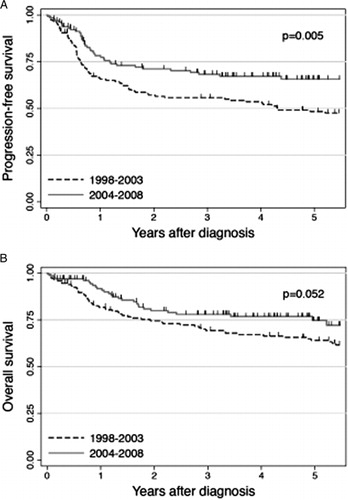

PFS and OS according to the time of diagnosis

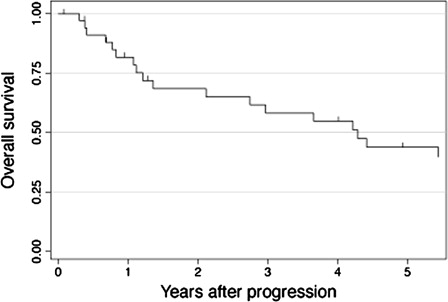

The median follow-up of surviving patients was 5.3 years (range, 0.1–13.2 years): 8.8 years (range, 0.3–13.2 years) for Cohort A and 4.2 years (range, 0.1–7.8 years) for Cohort B. Of the 147 patients in Cohort A, 61 were alive in CR1 and 23 were alive beyond CR1 at last follow-up. The remaining 63 patients died from lymphoma (N = 42), treatment-related toxicity (N = 5), second malignancy (N = 4), infection (N = 4), and other causes (N = 8). Of the 130 patients in Cohort B, 86 were alive in and 16 beyond CR1 at last follow-up, while 28 died from lymphoma (N = 23), treatment-related toxicity (N = 2), and other causes (N = 3). As shown in A, PFS was significantly better for Cohort B than for Cohort A, with 4-year PFS rates of 67.2 and 53.5%, respectively (P = 0.005). OS was also better for Cohort B than for Cohort A (76.8 and 67.1% at 4 years, B), although the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.052). In Cohort A, 35 patients received rituximab after disease progression. shows the Kaplan–Meier estimate of OS after progression for these 35 patients. The probability of OS was estimated to be 54.8% at 4 years after progression.

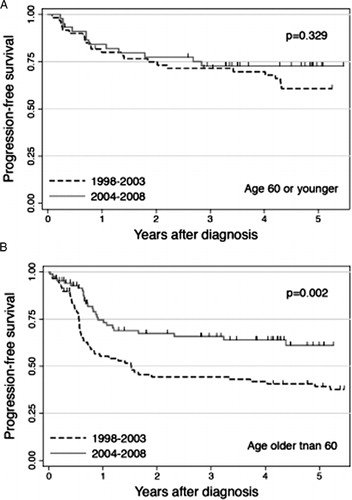

Subgroup analysis of differences in PFS according to the time of diagnosis

We next performed subgroup analyses to assess which patient population experienced improvement in PFS after the advent of rituximab. The 4-year PFS for each subgroup is listed in according to the time of diagnosis. For patients age 60 or younger, PFS of Cohorts A and B did not differ significantly (P = 0.329; A), whereas for patients over 60, Cohort B showed significantly better PFS than Cohort A (P = 0.002; B). In addition to age, PS, LDH level, and IPI risk appeared to be associated with some differences between those who did and did not show improvement in PFS (). Specifically, patients with PS 2-4, those with elevated LDH level, and those with high or high-intermediate IPI risk showed little or no improvement in PFS after the advent of rituximab.

Figure 3. PFS according to the time of diagnosis for (A) patients age 60 years or younger and (B) those older than 60 years. The numbers of patients diagnosed during 1998–2003 (Cohort A) and during 2004–2008 (Cohort B) were 60 and 45 for younger patients, and 87 and 85 for older patients, respectively.

Table 2. PFS at 4 years

Multivariate analysis for PFS

To evaluate whether the effect of the time of diagnosis on PFS remains significant after adjusting for other potentially confounding covariates, we performed a multivariate analysis. Factors included in the multivariate model were time of diagnosis, IPI risk, sex, presence of B symptom, and sIL-2R level. After adjusting for all of the remaining covariates, time of diagnosis was independently associated with PFS, with the HR of 0.61 (95% CI, 0.40–0.93; P = 0.021). The effect of time of diagnosis on PFS remained significant even if we included chemotherapeutic regimen (CHOP, CyclOBEAP, or others) in the multivariate model (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.35–0.85; P = 0.007).

Discussion

The beneficial effects of rituximab as first-line treatment for DLBCL have been demonstrated by four randomized controlled studies that compared CHOP or CHOP-like chemotherapy with and without rituximab.Citation3–Citation6 Although there is no doubt that those studies have contributed significantly to medical progress in this field, the question remains whether the results obtained with selected patient populations are valid for a general population of DLBCL patients. To clarify this issue, several groups performed retrospective comparisons of outcomes for DLBCL patients before and after the advent of rituximab.Citation8–Citation14 However, most of such studies included only patients who were treated intensively,Citation10–Citation14 and some studies compared outcomes in terms of the treatment actually given.Citation9,Citation11–Citation14 Furthermore, the follow-up of these previous studies was relatively short, ranging from 15 to 29 months for patients treated with rituximab, Citation8–Citation14 which makes it difficult to evaluate the effect of rituximab on long-term outcome. To overcome these limitations, we analyzed consecutive adult patients who were newly diagnosed with de novo DLBCL at our institution regardless of treatment. The results presented here are based on data with a median follow-up of 8.8 years for Cohort A (before the advent of rituximab), and of 4.2 years for Cohort B (after the advent of rituximab). In addition, all of the diagnoses of our patients were based on central pathological reviews. Discrepancies in pathological diagnoses do occur between local and central reviews,Citation22–Citation24 even after the introduction of the WHO classification in 2001. After removing such potential problems wherever possible, we attempted to evaluate whether and how rituximab contributed to the improvement in outcome of unselected DLBCL patients.

Our data showed that PFS of our patient population significantly improved after the advent of rituximab (P = 0.005). Improvement in OS was also noted, although the difference nearly attained statistical significance (P = 0.052). The less marked improvement in OS than in RFS can be best explained by the fact that subsets of patients diagnosed during the pre-rituximab era were successfully salvaged by rituximab-containing therapy after disease progression. As shown in , the 4-year probability of OS after progression was 54.8% for those in Cohort A who had shown progression and received rituximab thereafter. Our long-term follow-up data suggested that the use of rituximab after progression partly contributed to enhancement of OS for patients diagnosed prior to the introduction of rituximab. This observation led us to consider that a comparison of OS for Cohorts A and B would underestimate the true impact of rituximab, so that we limited the focus of subsequent analyses to PFS.

An examination of improvement in PFS for patients 60 years or younger and those over 60 found significant improvement for older patients (P = 0.002, B), but not for younger patients (P = 0.329, A). Similar results were reported by Ghesquieres et al.Citation8 Their observational study showed comparable event-free survival (EFS) for patients younger than 60 years before and after the advent of rituximab (77 vs. 74% at 3 years; P = 0.892), while for patients aged 60 or older, EFS significantly improved after the advent (37 vs. 65% at 3 years; P = 0.008). Their results and ours taken together, beneficial effect of rituximab is seemingly less significant in younger patients than in older patients, indicating the necessity of further investigations to improve outcome for younger patients.

As for IPI risk, improvement in PFS was less marked for patients with high or high-intermediate risk than for those with low or low-intermediate risk. Analysis of each element of the IPI score showed that being over 60 years old, which represents a high-risk feature, was conversely associated with greater improvement as also mentioned above. In terms of clinical stage and extranodal sites, improvement did not differ for patients with low- and high-risk features. For PS and LDH level, on the other hand, patients with high-risk features (PS 2 or higher and LDH level higher than the normal upper range) did not show improvement in PFS after the advent of rituximab (). These results suggest that the lesser benefit obtained with rituximab observed in our patients with high or high-intermediate IPI risk was mainly due to the fact that outcomes of patients with poor PS and those with elevated LDH remained unfavorable even after the advent of rituximab. In particular, the 4-year PFS for patients with PS 2-4 in Cohort B was only 32.8%, which was similar to the 32.4% for those with PS 2-4 in Cohort A. Since we analyzed all consecutive patients including those who had been treated less intensively and even those who had not been treated at all, it is possible that a substantial proportion of patients with poor PS did not receive sufficient therapy, and this may have had a greater impact on PFS than the presence or absence of rituximab.

When interpreting our results, it should be borne in mind that the retrospective nature of the study could be a potential source of bias. For instance, one may argue that the difference in distribution of baseline characteristics between Cohort A and Cohort B could affect the study results. Although our multivariate analysis accounting for potentially confounding factors also showed the beneficial effect of rituximab, adjusting for known confounding factors cannot guarantee that biases are removed. Thus, the results presented here need to be interpreted cautiously. Nevertheless, changes in outcome overtime can be better evaluated with a retrospective observational study. We also consider it important to analyze unselected patients including those who would not have met eligibility criteria of a prospective study. Acknowledging the above-mentioned limitations, our data indicate that the advent of rituximab has significantly improved outcomes for unselected patients with newly diagnosed de novo DLBCL, and that the improvement was greater for older than for younger patients. Further investigations are thus warranted in the hope of improving outcomes for younger patients with DLBCL.

Authorship and disclosures

A.O. and M.Y. designed the study, collected and analyzed the data, interpreted the results, and wrote the paper. Y.I., M.T., S.M., T.K., Y.Y., M.T., Y.A., S.M. performed research, and reviewed the paper. M.O. designed the study, collected the data, interpreted the results, and reviewed the paper. N.E. provided administrative support, interpreted the results, and reviewed the paper. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Hirokazu Nakamine, Dr Jun-Ichi Tamaru, Dr Shigeo Nakamura, Dr Tadashi Yoshino, Dr Koichi Ohshima, Dr Naoya Nakamura, and Dr Yoshikazu Mizoguchi for providing pathological reviews.

References

- Flowers CR, Sinha R, Vose JM. Improving outcomes for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:393–408.

- Izumo T, Maseki N, Mori S, Tsuchiya E. Practical utility of the revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms for Japanese non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91:351–60.

- Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–42.

- Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, Gascoyne RD, Cassileth PA, Cohn JB, et al. Rituximab-CHOP versus CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3121–7.

- Pfreundschuh M, Trumper L, Osterborg A, Pettengell R, Trneny M, Imrie K, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:379–91.

- Pfreundschuh M, Schubert J, Ziepert M, Schmits R, Mohren M, Lengfelder E, et al. Six versus eight cycles of bi-weekly CHOP-14 with or without rituximab in elderly patients with aggressive CD20+ B-cell lymphomas: a randomised controlled trial (RICOVER-60). Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:105–16.

- Elting LS, Cooksley C, Bekele BN, Frumovitz M, Avritscher EB, Sun C, et al. Generalizability of cancer clinical trial results: prognostic differences between participants and nonparticipants. Cancer 2006;106:2452–8.

- Ghesquieres H, Ferlay C, Sebban C, Chassagne C, Carausu L, Gargi T, et al. Combination of rituximab with chemotherapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Evaluation in daily practice before and after approval of rituximab in this indication. Hematol Oncol. 2008;26:139–47.

- Nagai H, Yano T, Watanabe T, Uike N, Okamura S, Hanada S, et al. Remission induction therapy containing rituximab markedly improved the outcome of untreated mature B cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:672–80.

- Sehn LH, Donaldson J, Chhanabhai M, Fitzgerald C, Gill K, Klasa R, et al. Introduction of combined CHOP plus rituximab therapy dramatically improved outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in British Columbia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5027–33.

- Park YH, Lee JJ, Ryu MH, Kim SY, Kim DH, Do YR, et al. Improved therapeutic outcomes of DLBCL after introduction of rituximab in Korean patients. Ann Hematol. 2006;85:257–62.

- Nishimori H, Matsuo K, Maeda Y, Nawa Y, Sunami K, Togitani K, et al. The effect of adding rituximab to CHOP-based therapy on clinical outcomes for Japanese patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a propensity score matching analysis. Int J Hematol. 2009;89:326–31.

- Seki R, Ohshima K, Nagafuji K, Fujisaki T, Uike N, Kawano F, et al. Rituximab in combination with CHOP chemotherapy for the treatment of diffuse large B cell lymphoma in Japan: a retrospective analysis of 1,057 cases from Kyushu Lymphoma Study Group. Int J Hematol. 2010;91:258–66.

- Bari A, Marcheselli L, Sacchi S, Marcheselli R, Pozzi S, Ferri P, et al. Prognostic models for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: a never-ending story. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1486–91.

- Gatter KC, Warnke RA. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. In: , Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW (eds.) World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: pathology and genetics of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC Press; 2001. 171–4.

- A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The international non-Hodgkin's lymphoma prognostic factors project. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:987–94.

- Niitsu N, Iijima K, Chizuka A. A high serum-soluble interleukin-2 receptor level is associated with a poor outcome of aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Eur J Haematol. 2001;66:24–30.

- Goto N, Tsurumi H, Goto H, Shimomura YI, Kasahara S, Hara T, et al. Serum soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R) level is associated with the outcome of patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP regimens. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:705–14.

- Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, Gascoyne RD, Specht L, Horning SJ, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:579–86.

- McKelvey EM, Gottlieb JA, Wilson HE, Haut A, Talley RW, Stephens R, et al. Hydroxyldaunomycin (Adriamycin) combination chemotherapy in malignant lymphoma. Cancer 1976;38:1484–93.

- Niitsu N, Okamoto M, Aoki S, Okumura H, Yoshino T, Miura I, et al. Multicenter phase II study of the CyclOBEAP (CHOP-like+etoposide and bleomycin) regimen for patients with poor-prognosis aggressive lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2006;85:374–80.

- LaCasce AS, Kho ME, Friedberg JW, Niland JC, Abel GA, Rodriguez MA, et al. Comparison of referring and final pathology for patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5107–12.

- Proctor IE, McNamara C, Rodriguez-Justo M, Isaacson PG, Ramsay A. Importance of expert central review in the diagnosis of lymphoid malignancies in a regional cancer network. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1431–5.

- Matasar MJ, Shi W, Silberstien J, Lin O, Busam KJ, Teruya-Feldstein J, et al. Expert second-opinion pathology review of lymphoma in the era of the World Health Organization classification. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:159–66.