Abstract

Background

Some pediatric patients, typically those that are very young or felt to be especially sick are temporarily admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for observation during their first transfusion. If a significant reaction that requires ICU management does not occur, these patients are then transferred to a regular ward where future blood products are administered. The aim of this project was to determine if heightened observation such as temporary ICU admissions for the first transfusion are warranted.

Methods

From the blood bank records of a tertiary care pediatric hospital, a list of patients on whom a transfusion reaction was reported between 2007 and 2012, the type of reaction and the patient's transfusion history, were extracted. The hospital location where the transfusion occurred, and whether the patient was evaluated by the ICU team or transferred to the ICU for management of the reaction was determined from the patient's electronic medical record.

Results

There were 174 acute reactions in 150 patients. Of these 150 patients, 13 (8.7%) different patients experienced a reaction during their first transfusion; all 13 patients experienced clinically mild reactions (8 febrile non-hemolytic, 4 mild allergic, and 1 patient who simultaneously had a mild allergic and a febrile non-hemolytic), and none required ICU management. Six severe reactions (6 of 174, 3.4%) involving significant hypotension and/or hypoxia that required acute and intensive management occurred during subsequent (i.e. not the first) transfusion in six patients.

Conclusions

The practice of intensive observation for the first transfusion in pediatric patients is probably unnecessary.

Keywords:

Introduction

Acute transfusion reactions are relatively uncommon events that occur during or shortly after the transfusion of a blood product. Reactions have been reported to occur at a rate of between 2.7 and 10.8% for patients admitted to a neonatal or pediatric intensive care unit (PICU),Citation1,Citation2 and between 3.8 and 10.6% in general pediatric patients,Citation3,Citation4 although in one study only reactions to leukoreduced platelet transfusions were considered.Citation4 A large, retrospective study of reaction data reported by 35 American academic pediatric hospitals demonstrated that reactions occur in only 0.95% of all transfused recipients, although the exact nature of many of the reported reactions was not presented.Citation5 Most reactions are mild, such as febrile non-hemolytic (FNHTR) and mild allergic reactions. Other less common reactions can be life threatening such as ABO incompatible reactions, severe allergic/anaphylaxis, transfusion associated circulatory overload (TACO), transfusion associated lung injury (TRALI), and bacterial contamination.Citation6 In one study, 15% of the reported reactions in PICU patients were considered severe and included three hypotensive reactions, one each of bacterial contamination, major allergic, and TRALI.Citation2 In the above-mentioned multicenter retrospective study of general pediatric patients, four anaphylactic reactions and five ABO incompatible reactions (two to platelets) were reported among the 51 720 patients who received a transfusion.Citation5

The management of many of these severe reactions often requires the patient to be admitted to the ICU for management. Some pediatric patients, typically those that are very young or felt to be especially sick, are, at the discretion of their attending physicians, temporarily admitted to the ICU for close observation during their first transfusion so that emergency treatment can be rapidly provided in the event that a severe transfusion reaction occurs. The patients who are admitted for observation during a transfusion do not require ICU admission for treatment of their underlying disease, but are admitted solely for close monitoring during their first transfusion. If a significant reaction does not occur, at the completion of the transfusion these patients are transferred to a regular ward where future blood products are administered as necessary.

ICU admissions are expensive, potentially stressful to the patient and their family, and beds in these wards are usually at a premium. The aim of this study was to determine if heightened observation, such as temporary ICU admissions, during the first transfusion are warranted by investigating the frequency of reactions during the first transfusion in pediatric patients.

Methods

A list of patients who had experienced a transfusion reaction from January 2007 to December 2012 at the Pittsburgh Children's Hospital of UPMC was extracted from the transfusion service's electronic records. This facility is a tertiary care hospital specializing in the care of children and features active trauma, surgery, and hematology/oncology services along with a variety of ICUs. The standard of care at this hospital is to provide leukoreduced cellular blood products, with irradiation, cytomegalovirus negative, and hemoglobin S negative products provided as necessary depending on the patient's age and disease. Premedication with anti-histamines or anti-pyretics before transfusion is at the discretion of the attending physicians.

Surveillance for acute transfusion reactions at this hospital is passive, and reporting of suspected reactions to the blood bank is at the discretion of the clinical team. All reactions that were reported to the blood bank were investigated by a transfusion medicine physician and the results were entered in the patient's electronic health record and that of the transfusion service. For each reported reaction, a laboratory investigation for hemolysis was performed on a post-reaction specimen that consisted of a clerical check, visual inspection of the plasma, and a direct antiglobulin test. Culturing of the blood product remnant was performed when clinically indicated, typically if a patient experienced a ≥2°C rise in temperature above their baseline or with evidence of shock following a transfusion.

For each patient on whom a reaction was reported to the blood bank, the type of reaction that the patient experienced (or whether the reported signs and symptoms were caused by the patient's underlying disease), and the number of blood products transfused before the first reaction occurred was documented from the blood bank's records. Additionally, the patient's clinical electronic medical record (EMR) was used to determine the age of the patient at the time of the first reaction, location in the hospital where the reaction occurred (ICU or non-ICU), the type of treatment that was required, if an ICU team was called to evaluate the patient during or after the reaction, and if the patient required ICU management of their reaction.

Continuous variables were analyzed with descriptive statistics. Tests for the normality of the data's distribution were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.04, San Diego, CA, USA). This protocol was approved by the Quality Improvement Board of the University of Pittsburgh, a division of the institutional review board.

Results

During the study period this pediatric hospital transfused an annual average of 7720 ± 570 red blood cell (RBC) units, 4570 ± 820 platelet doses, 4190 ± 1100 plasma units, and 440 ± 112 cryoprecipitate doses. For the 6-year study period there were approximately 101 580 blood products transfused at this hospital. After evaluation by a transfusion medicine physician using standard reaction definitions,Citation6 there were 174 reactions that occurred in 150 patients during the study period. During the study period there were an additional 61 ‘reactions’ that were reported to the blood bank that, after investigation by a transfusion medicine physician, were determined not to have been true transfusion reactions; instead the signs and symptoms that were reported as a reaction were actually caused by the patient's underlying disease and not the blood product (i.e. the patient did not experience a transfusion reaction).

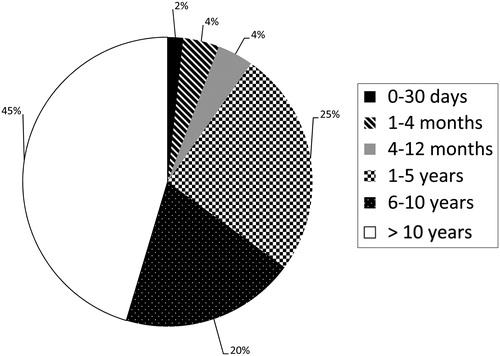

The distribution of the 174 reactions is demonstrated in . Included in the other category are two TACO reactions, and one isolated hypotensive reaction that was not associated with allergic signs or symptoms. Overall, acute reactions occurred following 1:580 (0.17%) of all transfused blood products; allergic reactions occurred following 1:1240 (0.08%) transfused blood products, and FNHTRs occurred following 1:1140 (0.09%) transfused units.

Figure 1. Distribution of the 174 transfusion reactions during the study period. In the other category are two TACO reactions, and one isolated hypotension reaction that was not associated with signs or symptoms of allergy.

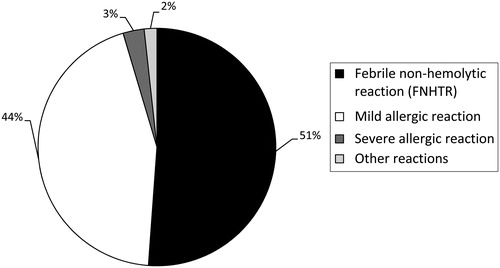

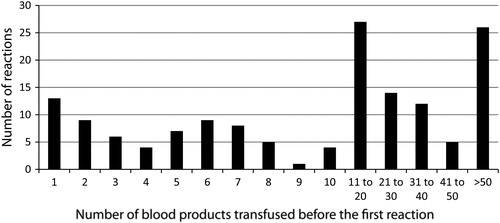

The median age at the time of the first transfusion reaction of these 150 patients was 9.0 years (range: 4 days to 26 years). shows the age distribution of these patients at the time of their first reaction. demonstrates the number of blood products that had been transfused before the first reaction occurred in these 150 patients. The median number of blood products that were administered before the first reaction occurred was 14 (range: 1–361). There were 13 of 150 (8.7%) individual patients who experienced a reaction during their first transfusion. The mean age of these 13 patients was 5.1 ± 5.7 years. All of these patients experienced clinically mild acute reactions including eight FNHTR, four mild allergic, and one patient who had both a mild allergic and FNHTR simultaneously. None of these patients required ICU consultation or management nor had any of them been temporarily admitted to the ICU for pre-emptive monitoring. Of these 13 patients who reacted to their first transfusion, 11 experienced reactions following an RBC transfusion, and 2 reactions were caused by platelets.

Figure 3. The number of blood products transfused before the first reaction occurred in the 150 patients, who experienced an acute transfusion reaction.

During the study period there were 6 of 150 (4.0%) individual patients whose reactions featured significant hypotension and/or hypoxia that required intensive management and potentially ICU consultation, or acute management by the anesthesiologist if the patient was transfused in the operating room (). Five of these were severe allergic reactions, and one reaction was categorized as hypotensive but not allergic. It was subsequently learned that one patient who experienced an anaphylactic reaction to RBCs had a history of severe allergic reactions to both shellfish and peanuts. None of these severe reactions occurred on the first transfusion; the median number of blood products transfused before these six severe reactions occurred was 8.5 (range 2–51). Five of these severe reactions were due to platelet transfusions and one occurred during a RBC transfusion. Overall there were 6 severe reactions among the 174 reported reactions (3.4%); the rate of severe transfusion reactions was 1:16 930 transfused blood products.

Table 1. Clinical details on the six patients who experienced severe acute transfusion reactions

Discussion

At this tertiary care pediatric hospital, patients are occasionally admitted to the ICU for close monitoring during their first transfusion. Subsequent transfusions are then administered on a regular ward. The patients selected for temporary ICU admission for observation during transfusion are typically those that are felt to be ‘sicker’ than expected given their disease, or perhaps are young and underweight. There are no formal criteria at this hospital for selecting patients for temporary ICU admission for observation during transfusion. Underlying this practice is the assumption that if a severe reaction is going to occur, then it will occur during the first transfusion. However, severe reactions that might require ICU management such as acute hemolytic reactions caused by ABO incompatibility, bacterial contamination, and TRALI can occur during any transfusion as these events depend more so (but not entirely) on factors that are related to the donor rather than on the recipient's disease state. Thus, tolerating the first transfusion without incident is not necessarily a positive prognostic indicator for tolerating future transfusions. During the 6-year study period at this pediatric hospital, only 8.7% of the reactions occurred during the first transfusion, and none of them were severe enough to require aggressive management, or ICU consultation or admission. Thus, given the small number of reactions to the first transfusion, and the overall infrequent occurrence of severe reactions that required intensive or actual ICU management, we suggest that pediatric patients do not require intensive monitoring, such as temporary ICU admissions for observation, during their first transfusion.

There might be several uncommon situations where closer than usual monitoring of the recipient, or even pre-emptive admission to the ICU for monitoring, during a transfusion is warranted. For example, a patient with a history of severe allergic reactions or anaphylaxis to blood products who requires a transfusion so urgently that the time required to wash the RBCs or platelets would jeopardize their life could receive their transfusion in an ICU setting such that prompt airway and blood pressure management could be provided if necessary. Another example might be a patient with severe pre-existing circulatory overload, who requires an urgent transfusion before dialysis or diuretics can be administered. This type of patient might also benefit from the ability to rapidly manage their airway should the transfusion worsen their respiratory status. However, as it is generally not possible to predict when a transfusion reaction will occur, and as most reactions are mild – in this series approximately 95% of all of the reactions were either mild allergic or FNHTR; the vast majority of transfusion recipients will not benefit from close observation during their first transfusion.

In this study, the overall rate of transfusion reactions was 0.17% for all transfused blood products. This reaction rate is somewhat lower than the rates of 1.3 and 1.6% that were previously demonstrated in neonatal and PICU patients.Citation1,Citation2 One possible explanation for the higher reaction rate was that these two studies employed active surveillance for reactions by the bedside nurses during each transfusion, thereby perhaps sensitizing the nurses to these events and leading to higher reporting rates. It is unclear why our reaction rate of 0.17% to all transfused blood products was also lower than the 1.3% rate observed in a study of a general pediatric population that was also based on passive reporting of reactions.Citation3 The rate of FNHTR following transfusion in the current study was 0.09%, which was slightly lower than the 0.19% rate seen in two previous studies of FNHTR in the general population of leukoreduced blood product recipients.Citation7,Citation8

This study has several limitations. As the reporting of suspected transfusion reactions to the blood bank was passive and depended on the clinical team's recognition and reporting of the reaction, it is possible that not all reactions were captured in the blood bank's database. Thus the number of severe reactions and the number of reactions to the first transfusion might be higher than reported herein. However, as there were numerous reports of suspected reactions that were subsequently determined not to have been transfusion reactions, it is unlikely that a severe reaction would not have been reported to the blood bank. Also, due to a limitation in the EMR, it was not possible to determine how many patients were temporarily admitted to the ICU for monitoring during their first transfusion and did not have a reaction. Thus it is not possible to determine the scope of this practice or the exact demographics of the patients who were temporarily admitted to the ICU for transfusion at this hospital. Owing to the same limitation in this hospital's EMR, it was also not possible to determine the number of unique patients that received a transfusion; hence, the frequency of reactions is expressed per transfused blood product, not recipient.

In this study, we have demonstrated low rates of transfusion reactions following the patient's first transfusion, and also low rates of severe reactions that required ICU support. Thus, pediatric patients do not appear to require closer than usual monitoring during their first transfusion, although these results should be confirmed in larger studies that are based on prospective monitoring of patients for reactions.

References

- Boo NY, Chan BH. Blood transfusion reactions in Malaysian newborn infants. Med J Malaysia 1998;53:358–64.

- Gauvin F, Lacroix J, Robillard P, Lapointe H, Hume H. Acute transfusion reactions in the pediatric intensive care unit. Transfusion 2006;46:1899–908.

- Pedrosa AK, Pinto FJ, Lins LD, Deus GM. Blood transfusion reactions in children: associated factors. J Pediatr. 2013;89(4):400–6.

- Couban S, Carruthers J, Andreou P, Klama LN, Barr R, Kelton JG, et al. Platelet transfusions in children: results of a randomized, prospective, crossover trial of plasma removal and a prospective audit of WBC reduction. Transfusion 2002;42:753–8.

- Slonim AD, Joseph JG, Turenne WM, Sharangpani A, Luban NL. Blood transfusions in children: a multi-institutional analysis of practices and complications. Transfusion 2008;48:73–80.

- Roback JD, AABB. Technical manual. 17th ed. Bethesda, MD: AABB; 2011.

- Yazer MH, Podlosky L, Clarke G, Nahirniak SM. The effect of prestorage WBC reduction on the rates of febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions to platelet concentrates and RBC. Transfusion 2004;44:10–15.

- Paglino JC, Pomper GJ, Fisch GS, Champion MH, Snyder EL. Reduction of febrile but not allergic reactions to RBCs and platelets after conversion to universal prestorage leukoreduction. Transfusion 2004;44:16–24.