Abstract

Objective and importance

Acquired haemophilia is a rare hemorrhagic disease caused by inhibitory autoantibodies against coagulation factor VIII. Rituximab has become a popular choice for immunosuppressive therapy in acquired haemophilia, almost with the same schedule of 375 mg/m2 per week for 4–6 doses. While the effect of low-dose rituximab has seldom been reported.

Clinical presentation

We report a patient, aged 88 years, who developed acquired haemophilia with severe hemorrhage and elevation of carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125), but in the absence of a detectable cause.

Intervention

We prescribed a low-dose rituximab alone (100 mg per week for a total of four infusions) for the patient, different from the conventional usage, but received a similar effect. In addition, the patient was diagnosed with immune thrombocytopenia 22 months after rituximab, while FVIII activity and activated partial thromboplastin time remained within the normal range. After four infusions of low-dose rituximab, the platelet count recovered.

Conclusion

At a follow-up of 34 months, the patient remains in remission without further treatment, suggesting low-dose rituximab seems to be a safe and effective regimen for the elderly patients with acquired haemophilia.

Introduction

Acquired haemophilia is a potentially life-threatening bleeding disorder occurring in patients without a previous personal or family history of bleeding. Rituximab has shown promise as a safe and effective therapy when used alone or in combination with other immunosuppressive agents as second-line therapy. In most studies, rituximab was conventionally prescribed as 375 mg/m2 intravenously per week for 4–6 doses, while the effect of low-dose rituximab has seldom been reported. Here, we report a case of acquired haemophilia with severe hemorrhage who was successfully treated with low-dose rituximab. Specifically, there was a decline in platelet count 22 months after rituximab, and further examination suggested immune thrombocytopenia. What is the relationship between acquired haemophilia and immune thrombocytopenia? There are no similar cases reported.

Case report

An 88-year-old man was first admitted to the hospital in February 2010 for obvious bleeding tendency with no history of personal or familial bleeding and medications. He had an extensive subcutaneous haematoma from the left face to the cervical region, accompanied by toothace. There was no hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or enlarged lymph node. Except for bleeding manifestations, clinical examination was unremarkable.

Blood tests showed low white blood cell count (2.95 × 109/l), but haemoglobin (Hb 128 g/l) and platelet (PLT 122 × 109/l) were normal. Coagulation tests revealed markedly prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) at 76.1 seconds (control: 21–35 seconds), and low activity of coagulation factor FVIII/FIX/FXI/FXII (FVIII 1.9%, FIX 7.2%, FXI 6.8%, FXII 7.5%). Other coagulation tests including prothrombin time, thrombin time, and fibrinogen, were in the normal range. Next we examined the autoantibodies, but neither lupus anticoagulant nor anticardiolipin antibodies were detected. Particularly, the serum level of carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125) was elevated at 59.54 mmol/l (control: 0–39), but whole body positron emission tomography-computed tomography (CT)scan was negative, and there was no evidence of tumour, lymphoproliferative, or autoimmune disease upon further investigation. Thus, the patient was suspected with acquired coagulation factor deficiency.

After several infusions of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and recombinant human coagulation factor VIII (rFVIII), the enlarged haematoma gradually resolved, with a partial and transient APTT/FVIII correction, speculating the interference by FVIII inhibitors. Then APTT and coagulation factors were further investigated by mixing studies using mixtures of patient's plasma 1/1 ratio with normal plasma. The test allowed the recovery of normal FIX FXI and FXII activity with the exception of prolonged APTT and low FVIII activity (APTT 75 seconds, FVIII 1.9%, FIX 65.8%, FXI 33%, FXII 35%). These preliminary results suggested the presence of FVIII inhibitors.

The patient was first treated with desmopressin (DDAVP) at a dose of 0.3 µg/kg in May 2010, with intermittent infusion of rFVIII, but without obvious efficiency. Given the advanced age and his hypertension and diabetes, long-term steroid should not be the preferred use. He was then received 3 days of methylprednisolone at a dose of 40 mg/day, in combination with intravenous immunoglobulins (0.4 g/kg/d). But efficacy on the patient was limited. FVIII activity increased from a pre-therapy value of 4.4% to 11.9%, and APTT droped from 59.7 to 49.2 seconds. The patient was discharged home.

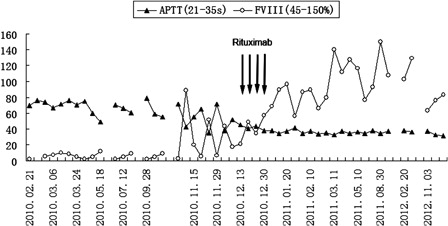

The patient was admitted to hospital again in November 2010, for extensive haematoma of the abdomen and left hip. Laboratory tests showed moderate anaemia (Hb 84 g/l), markedly prolonged APTT at 65.4 seconds, FVIII activity 5.7%, and FVIII inhibitors quantified at 68 BU. Autoantibody tests associated with rheumatological disorders were negative. The level of CA125 progressively increased to 79.9 mmol/l, but thoraco-abdomino-pelvic CT scan was negative and no evidence of tumour. Subsequently, FFP and rFVIII were administered. FVIII activity could temporarily increase to 51.9%, but rapidly decreased to 6.7% five days later. Given the patient's age and risk of infection, we decided to prescribe low-dose rituximab alone (100 mg per week) for a total of four infusions. Surprisingly, One week after the first rituximab infusion, FVIII activity increased from a pre-therapy value of 17.4 to 34.1%, and APTT dropped to 43 seconds. With the rest infusions of rituximab, FVIII activity increased gradually () and FVIII inhibitors decreased. One week after the fourth rituximab infusion, FVIII activity increased to 89.6%, APTT was normal at 33.9 seconds, and the FVIII inhibitors decreased to 5 BU. But unfortunately 2 weeks later, the patient suffered from herpes zoster, and there was a slight decline in FVIII activity (55.8%). After 5 days antiviral treatment, FVIII activity restored normal (86.9%). The patient was discharged home, without any sequential therapy.

Figure 1. Change in activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) and factor VIII acticity (FVIII) with general regimen and rituximab therapy. The arrows represent the time of each rituximab infusion. Rituximab (100 mg) was given at December 17, 24, 31, 2010 and January 7, 2011. FVIII inhibitors detected less, not listed in the figure.

During the following up period of 22 months after rituximab, FVIII activity, and APTT remained within the normal range, FVIII inhibitor was undetectable, but there was a decline in platelet count (PLT 40–42 × 109/l) without bleeding tendency since November 2012. At the same time, the level of CA125 increased to 112.6 mmol/l, but remaining no radiographic or clinical evidence of tumour. Bone marrow cytology showed megakaryocytic maturation disorder with thrombocytopenia. Further examination suggested immune thrombocytopenia. After four infusions of rituximab (100 mg per week), platelet count rose to a maximum of 86 × 109/l.

Up to date (October 2013), the patient remains in remission condition after a follow-up of 34 months.

Discussion

Acquired haemophilia is a rare hemorrhagic disease caused by inhibitory autoantibodies against coagulation factor VIII (FVIII), which arise spontaneously in approximately 1–1.5 per million persons annually.Citation1,Citation2 In acquired haemophilia, APTT is prolonged whereas prothrombin time and platelet function are normal. Factor VIII activity is low. This condition often occurs in the elderly, and the bleeding manifestations more frequently present with mucocutaneous bruising or soft tissue bleeding.

In a recently published clinical data of 501 patients with acquired haemophilia from EACH2,Citation3 467 diagnosis were triggered by a bleeding event. At diagnosis, patients were a median of 73.9 years. Acquired haemophilia was idiopathic in 51.9%, and 10% of patients were associated with underlying malignancy, either solid or haematologic.Citation1,Citation4 Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) represents 30% of the haematologic malignancies,Citation5 while prostate cancer and lung cancer each account for about 25% of solid tumours.Citation6,Citation7 Furthermore, it is unclear what proportion will develop into malignancy in those initially diagnosed with idiopathic acquired haemophilia. In this case, we did not find any pathogenic reason except the elevation of CA125.

CA125 is a glycoprotein produced by cells derived from the celomic epithelium of the female genital tract, the mucosa of the colon and stomach, and mesothelial cells of the serous membranes. CA125 was established as a prognostic marker in cancer, especially in ovarian and gastric carcinoma. Many studies also reported serum elevations of CA125 in 40% of patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, particularly when peritoneal, pleural, or pericardial effusions are present.Citation8 So initially, we speculated there probably was an underlying malignancy, requiring more prolonged follow-up.

However, recent studies suggested that CA125 levels were remarkably elevated in patients with heart failure, and along with the presence of pleural fluid or peripheral edema in patients aged 85 years and older with chronic heart failure. It has emerged as a potential biomarker in heart failure.Citation9 In this case, the patient suffered from chronic atrial fibrillation and coronary artery disease. Maybe, the elevation of CA125 was associated with the poor heart function, since there was no evidence of malignancy.

Due to the relative rarity of the condition and consequent lack of awareness, diagnosis of acquired haemophilia is often delayed. And delayed diagnosis significantly impacted treatment initiation in 33.5%.Citation3 We retrospectively reviewed our case, the performance of acquired haemophilia has been typical on his first admission. However, we focused on his elevation of CA125 initially, thus lost the quantitative examination of FVIII inhibitors and delayed the diagnosis of acquired haemophilia.

The treatment for acquired haemophilia is directed at bleeding control, inhibitor eradication to prevent subsequent bleeding episodes, and treatment of any underlying causative disease. Several strategies, such as desmopressin, rFVIII, or porcine FVIII (pFVIII), may raise FVIII activity. The patient was first treated with desmopressin, rFVIII, methylprednisolone, and in combination with intravenous immunoglobulins, but without apparent effect, suggesting that the FVIII inhibitors titre was high. From the literature review, we know rFVIII and/or DDAVP were used as first-line agents in patients with acute bleeding, and only considered in patients with low inhibitor level (<5 BU), or if first-line agents are not readily available. Therefore, the quantitative examination of FVIII inhibitors is of guiding significance for the treatment of acquired haemophilia.

Since the patient had been failed from maintenance regimens, furthermore taking into account his hypertension and diabetes, long-term steroid as prednisone 0.5∼1 mg/kg should not be the preferred use. As reported, lower doses of rituximab had been shown to be effective in the treatment of immune thrombocytopeniaCitation10 and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.Citation11 We prescribed low-dose rituximab (100 mg per week for four doses) for the patient. Surprisingly, we received a significant effect, and the time to remission was short.

Rituximab has become a popular choice for immunosuppressive therapy in patients with acquired haemophilia,Citation12 almost with the same schedule of 375 mg/m2 per week for four to six doses. Two reviews suggest a complete response rate of over 80% when rituximab is given as first- or second-line therapy to patients with acquired haemophilia,Citation12,Citation13 and sustained responses often occur when patients are treated with rituximab-containing regimens.Citation14 While most of the patients received other forms of immunosuppressive therapy in addition to rituximab, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions about the duration of response to rituximab as a single agent. In this case, the patient received rituximab only, no sequential steroids or other immunosuppressive therapy.

Late adverse events of rituximab include late-onset neutropenia, defects of immune reconstitution and secondary infections. Late-onset neutropenia has been reported in 5–27% of lymphoma patients treated with rituximab.Citation15 The identification of neutropenia after rituximab may have immediate implications for the clinical management of the patient and on subsequent treatment strategies.Citation16 These findings suggest that monitoring for late-onset neutropenia may be necessary after rituximab therapy, especially in elderly patients who may have increased susceptibility to infections. In this case, we did not encounter late-onset neutropenia and other unpredictable side effects. But, there was a decline in platelet count 22 months after rituximab, and further examination suggested immune thrombocytopenia. We try to find out the relationship between acquired haemophilia and immune thrombocytopenia. Unfortunately, there are no similar cases reported.

In conclusion, low-dose rituximab in our observation gets a similar effect to the conventional dose, and the sustained response is significantly. It seems to be a safe and effective regimen for the elderly patients with acquired haemophilia. Nevertheless, the overall effects of this regimen need further evaluation in controlled trials.

References

- Green D, Lechner K. A survey of 215 non-hemophilic patients with inhibitors to factor VIII. Thromb Haemost. 1981;45:200–3.

- Huth-Kuhne A, Baudo F, Collins P, Ingerslev J, Kessler CM, Lévesque H, et al. International recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of patients with acquired hemophilia A. Haematologica 2009;94:p566–75.

- Knoebl P, Marco P, Baudo F, Collins P, Huth-Kühne A, Nemes L, et al. Demographic and clinical data in acquired hemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia Registry (EACH2). J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:622–31.

- Reeves BN, Key NS. Acquired hemophilia in malignancy. Thromb Res. 2012;129 (Suppl 1):S66–8.

- Franchini M, Targher G, Montagnana M, Lippi G. Laboratory, clinical and therapeutic aspects of acquired hemophilia A. Clin Chim Acta 2008;395:14–8.

- Hauser I, Lechner K. Solid tumors and factor VIII antibodies. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82:1005–7.

- Sallah S, Wan JY. Inhibitors against factor VIII in patients with cancer. Analysis of 41 patients. Cancer 2001;91:1067–74.

- Procházka V, Faber E, Raida L, Kapitáňová Z, Langová K, Indrák K, et al. High serum carbohydrate antigen-125 (CA-125) level predicts poor outcome in patients with follicular lymphoma independently of the FLIPI score. Int J Hematol. 2012;96:58–64.

- Vizzardi E, D'Aloia A, Curnis A, Dei Cas L. Carbohydrate antigen 125: a new biomarker in heart failure. Cardiol Rev. 2013;21:23–6.

- Zaja F, Battista ML, Pirrotta MT, Palmieri S, Montagna M, Vianelli N, et al. Lower dose rituximab is active in adults patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Haematologica 2008;93:930–3.

- Pequeño-Luévano M, Villarreal-Martínez L, Jaime-Pérez JC, Gómez-de-León A, Cantú-Rodríguez OG, González-Llano O, et al. Low-dose rituximab for the treatment of acute thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: report of four cases. Hematology 2013;18:233–6.

- Garvey B. Rituximab in the treatment of autoimmune haematological disorders. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:149–69.

- Franchini M. Rituximab in the treatment of adult acquired hemophilia A: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;63:47–52.

- Singh AG, Hamarneh IS, Karwal MW, Lentz SR. Durable responses to rituximab in acquired factor VIII deficiency. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:172–4.

- Tesfa D, Palmblad J. Late-onset neutropenia following rituximab therapy: incidence, clinical features and possible mechanisms. Expert Rev Hematol. 2011;4:619–25.

- Wolach O, Shpilberg O, Lahav M. Neutropenia after rituximab treatment: new insights on a late complication. Curr Opin Hematol. 2012;19:32–8.