Background

I was surprised to come across a senior colleague using acupuncture in the British military when I started my general practice training. I had joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) rather than a civilian vocational training scheme, because I was interested in musculoskeletal pain and sports medicine. I trained in Western medical acupuncture with the British Medical Acupuncture Society and found dry needling appeared to be a very useful intervention in soft tissue pain, particularly muscle pain.Citation1 After 7 years in the RAF as a general duties medical officer, I retired to pursue a career in orthopaedic medicine, but having taken over an established medical acupuncture practice, I found myself mostly in demand for acupuncture services. It was the early 1990s and systematic reviews (SRs) had just been developed, and Adrian White, one of my former acupuncture tutors, got me involved in both performing and reviewing SRs.Citation2

The first meta-analysis of acupuncture was performed by Ernst and White in 1998,Citation3 and this reported that acupuncture was superior to non-acupuncture controls. A subsequent SR by the Cochrane Collaboration Back Group (van Tulder et al.Citation4) opted to avoid data pooling in meta-analysis, and instead performed a best evidence synthesis within a qualitative review. Van Tulder et al. concluded that there was no evidence for an effect of acupuncture in back pain. This conclusion was a shock to me after the positive meta-analysis by Ernst and White, so I read the entire review. The conclusions were influenced by one of the two trials that were judged to be ‘high quality’. I knew this trial well, as it had been included in my first SR – Garvey et al.Citation5 It was with some consternation that I realized the conclusions of an SR of acupuncture could be influenced by reviewers opinions over a trial that had not actually used acupuncture needles at all – Garvey et al. used insertion of a hypodermic needle at a single point and referred to it as acupuncture. So this was the start of my evolving understanding of the limitations, within the review process, of championing the avoidance of bias over the judgement of clinicians.

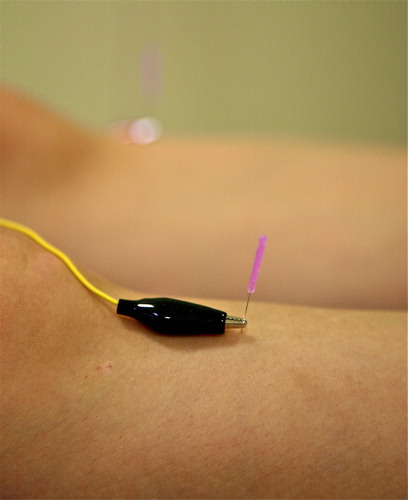

Electroacupuncture for osteoarthritis

As my clinical practice developed, I gained the impression that electroacupuncture (EA) was superior to manual acupuncture in chronic musculoskeletal pain – mostly osteoarthritis (OA) (see ). As the trial data in the area of acupuncture for OA increased, I suspected that this might be the first area in which NICE guidelines recommended the use of acupuncture, and I set about convincing my colleague Adrian White that we should perform a SR with meta-analysis of acupuncture for chronic knee pain.Citation6 We found a statistically significant benefit for acupuncture over sham acupuncture, and a larger effect for acupuncture over all controls. Another group performed a meta-analysis at the same time, and while their numerical results were very similar (standardized mean difference – SMD – of −0.35 over sham, and −0.96 over waiting list), the conclusion of their paper raised the issue of the lack of a clinically relevant difference between real and sham acupuncture.Citation7 Later, it was suggested by Madsen et al.Citation8 that while the difference between real and sham acupuncture in three armed trials of acupuncture in all forms of pain was statistically significant (SMD −0.17 for real over sham, −0.42 for sham over no acupuncture controls), it could probably be accounted for by the bias of unblinded practitioners. The authors failed to provide any evidence for their hypothesis, and failed to explain how it was possible for practitioners to systematically influence the results when the outcome assessments were performed blind to allocation and patient blinding was maintained throughout in most trials. Despite the lack of support for the hypothesis of Madsen et al., the idea crept into the bottom line of the subsequent Cochrane review of acupuncture in peripheral joint OA:Citation9

Sham-controlled trials show statistically significant benefits; however, these benefits are small, do not meet our pre-defined thresholds for clinical relevance, and are probably due at least partially to placebo effects from incomplete blinding.

Adrian White and I argued in a BMJ editorial,Citation10 published simultaneously with the paper of Madsen et al., that clinical relevance should not be attributed to the difference between real and sham acupuncture, principally because sham acupuncture was often a gentler form of the active treatment itself. This argument seems to be overlooked despite the effect of sham acupuncture significantly outperforming guideline-based conventional care in large trials.Citation11

NICE guidelines

The first guideline to consider acupuncture was CG59, published in 2008.Citation12 The draft of this guideline recommended acupuncture but not EA, but the final guideline included the following:

R15 Electro-acupuncture should not be used to treat people with osteoarthritis.

There is not enough consistent evidence of clinical or cost-effectiveness to allow a firm recommendation on the use of acupuncture for the treatment of osteoarthritis.

It seems clear from reading the full guideline and appendices that the negative recommendation for EA was based purely on health economic modelling from a secondary outcome (WOMAC) in a single randomised controlled trial (RCT) (n = 193).Citation13 It is of passing interest but no consequence to note that the primary outcome of the same RCT demonstrated EA to be superior to diclofenac in treatment of pain related to OA knee. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were recommended as adjuncts to core therapy in the guideline. Detailed discussions for and against the health economic modelling against placebo can be found in a debate article in the June 2009 issue of Acupuncture in Medicine.Citation14,Citation15 This debate was moved forward by the publication of a reanalysis of the health economic modelling by the same health economist involved in CG59, but on the basis of a comparison with usual care (more pragmatic) rather than with sham (the usual approach of NICE).Citation16 A primary health economic evaluation associated with a trial of acupuncture for OA within the UK was also published,Citation17 and demonstrated an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for acupuncture of £3889 per additional quality-adjusted life year: a figure even lower than was produced by modelling in comparison to usual care.

Figure 1. The image shows EA applied to ST36, a point in tibialis anterior about a hand width below the knee joint line. This point is frequently used in treatment of symptoms related to OA knee, along with points in quadriceps femoris.

So it seemed that we need only wait for an update on the guideline in the expectation that acupuncture had cleared the final hurdle. CG177 was published in February 2014,Citation18 but it did not recommend acupuncture in OA. This time a new hurdle had been erected. Interventions would have to meet or exceed a minimum important difference (MID) over placebo. While there were data available on the MID in OA knee (SMD 0.33) and other joints,Citation19 the guideline development group decided this would be too complicated to adopt, and settled on a figure of 0.5, which corresponded to the default setting on the software they were using (GRADEpro).Citation18 There are few interventions that can be demonstrated to achieve an SMD of 0.5 over placebo in OA. Of course the data on MID was not generated against placebo, but in a large cohort study where patients were started on, or changed their NSAIDs, so the effect they were experiencing included both specific effects of the intervention and context effects. Since context effects are estimated to make up about 50% of the effect of pain treatments (such as opioids) in clinical practice,Citation20 by insisting on a MID over placebo as opposed to a change from baseline in a cohort study (or a within group change in an RCT), the NICE approach is likely to withhold recommendations for interventions such as acupuncture and EA, which clearly have a clinically relevant effect in practice.

References

- Cummings TM. A computerised audit of acupuncture in two populations: civilian and forces. Acupunct Med 1996;14:37–9.

- Cummings TM, White AR. Needling therapies in the management of myofascial trigger point pain: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001;82:986–92. doi:10.1053/apmr.2001.24023.

- Ernst E, White AR. Acupuncture for back pain: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:2235–41. PM:0009818803.

- Van Tulder MW, Cherkin DC, Berman B, et al. The effectiveness of acupuncture in the management of acute and chronic low back pain. A systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24:1113–23. PM:0010361661.

- Garvey TA, Marks MR, Wiesel SW. A prospective, randomized, double-blind evaluation of trigger-point injection therapy for low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989;14:962–4. PM:0002528826.

- White A, Foster NE, Cummings M, et al. Acupuncture treatment for chronic knee pain: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:384–90. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kel413.

- Manheimer E, Linde K, Lao L, et al. Meta-analysis: acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:868–77. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17577006.

- Madsen MV, Gøtzsche PC, Hróbjartsson A. Acupuncture treatment for pain: systematic review of randomised clinical trials with acupuncture, placebo acupuncture, and no acupuncture groups. BMJ 2009;338:a3115. doi:10.1136/bmj.a3115.

- Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010:CD001977. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001977.pub2.

- White A, Cummings M. Does acupuncture relieve pain? BMJ 2009;338:a2760. doi:10.1136/bmj.a2760.

- Haake M, Muller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, et al. German Acupuncture Trials (GERAC) for chronic low back pain: randomized, multicenter, blinded, parallel-group trial with 3 groups. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1892–8. PM:17893311.

- NICE guideline on osteoarthritis: the care and management of osteoarthritis in adults. 2008. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG59.

- Sangdee C, Teekachunhatean S, Sananpanich K, et al. Electroacupuncture versus diclofenac in symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 2002;2:3. PM:11914160.

- White A. NICE guideline on osteoarthritis: is it fair to acupuncture? No. Acupunct Med 2009;27:70–2. PM:19502464.

- Latimer N. NICE guideline on osteoarthritis: is it fair to acupuncture? Yes. Acupunct Med 2009;27:72–5. PM:19502465.

- Latimer NR, Bhanu AC, Whitehurst DGT. Inconsistencies in NICE guidance for acupuncture: reanalysis and discussion. Acupunct Med 2012;30:182–6. doi:10.1136/acupmed-2012-010152.

- Whitehurst DG, Bryan S, Hay EM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of acupuncture care as an adjunct to exercise-based physical therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee. Phys Ther 2011;91:630–41. PM:21415230.

- NICE guideline update on osteoarthritis: the care and management of osteoarthritis in adults. Published Online First: 2014. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG177.

- Tubach F, Ravaud P, Baron G, et al. Evaluation of clinically relevant changes in patient reported outcomes in knee and hip osteoarthritis: the minimal clinically important improvement. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:29–33. PM:15208174.

- Benedetti F, Mayberg HS, Wager TD, et al. Neurobiological mechanisms of the placebo effect. J Neurosci 2005;25:10390–402. PM:16280578.