Abstract

Background:

Real-world data on the pharmacological management of men who have lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) are limited.

Objective:

To characterize men with LUTS/BPH who had both storage and voiding symptoms and to evaluate treatment patterns in UK primary care.

Design, setting and participants:

This was an observational study of men aged ≥45 years with a diagnosis, symptoms or therapies indicative of LUTS/BPH with both storage and voiding components. These men were identified from the large Health Improvement Network (THIN) database between 1 January 2004 and 30 September 2011.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis:

Drug prescriptions and switching/discontinuation patterns for α1-blockers and antimuscarinics.

Results and limitations:

We identified 8694 men with a median age of 66.0 (interquartile range [IQR], 59.0–74.0) years. Most (7850; 90.3%) received an α1-blocker, and 2167 (24.9%) received antimuscarinic therapy over a median of 2.1 years. The most commonly prescribed α1-blocker was tamsulosin (81.8%); most frequent antimuscarinics were tolterodine (41.0%), oxybutynin (37.2%) and solifenacin (35.7%). Concomitant prescription of α1-blocker and antimuscarinic therapy (within 30 days of each other) was received by 1160 men (14.8% of α1-blocker-treated men). Of α1-blocker recipients, 3024 (38.5%) discontinued during follow-up, while 1149 (53.0%) discontinued antimuscarinic therapy. Of 2167 men who received an antimuscarinic, 476 (22.0%) switched to another antimuscarinic. Of the three most commonly prescribed antimuscarinics, solifenacin had the lowest proportions of discontinuations (43.0%) and switches (15.3%), and the longest median duration of therapy (90 days, IQR 30–300). General practice consultations accounted for most resource use (5307.9 per 1000 patient-years).

Conclusions:

This study presents real-world management of men with LUTS/BPH who have both storage and voiding symptoms. The low proportion of men who received concomitant α1-blocker and antimuscarinic therapy suggests that some patients are sub-optimally treated in routine clinical practice.

Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) can be categorized into voiding (e.g., slow stream, splitting/spraying, intermittency, hesitancy, straining, and terminal dribble), storage (e.g., daytime urinary frequency, urgency, urinary incontinence, nocturia) and post-micturition (e.g., feeling of incomplete emptying and post-micturition dribble) symptomsCitation1. Storage symptoms are reportedly the most bothersome of the LUTSCitation2,Citation3.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common cause of LUTS in men aged >40 yearsCitation4. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) estimates that 90% of men 50 to 80 years of age experience troublesome LUTS, with storage symptoms increasing from 3% at age 40–44 years to 42% from 75 yearsCitation1. The resource burden of LUTSCitation5 is accompanied by loss of health-related quality of life (HRQoL), including significant effects on general health status and mental healthCitation6. In the worst cases, sleep may be disturbed by nocturia up to 10 times a nightCitation5.

Treatment guidelines recommend that men with moderate-to-severe LUTS are offered an α1-blocker (e.g., tamsulosin, alfuzosin, terazosin, doxazosin); 5α-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs; dutasteride, finasteride) in those with a large prostate (>30 gCitation1 or >40 mlCitation4); and an antimuscarinic (e.g., oxybutynin, tolterodine, solifenacin) in those with predominant storage symptomsCitation1,Citation3,Citation4. The benefits of combination treatment with an α1-blocker and an antimuscarinic have been recognized over the last decade, supported by improved symptoms and quality of life reported in several large randomized trialsCitation7–13. Consequently, an α1-blocker in combination with an antimuscarinic is recommended for patients with moderate-to-severe LUTS/BPH if symptom relief is insufficient with monotherapy of either drugCitation1,Citation4.

Despite the high prevalence of LUTS/BPH, real-world data on day-to-day pharmacological management are limited. This study was performed to describe the demographics of men with LUTS/BPH who have both storage and voiding symptoms, and to evaluate drug usage patterns and healthcare resource use in the UK primary care setting.

Materials and methods

Data source

This was a retrospective observational cohort study of healthcare provided by general practitioners (GPs) in the UK, where drug treatment for LUTS is frequently initiated in primary careCitation1. Data were sourced from the large general practice database, The Health Improvement Network (THIN; see Supplementary Information)Citation14. Medical research conducted with THIN requires Scientific Review Committee (SRC) approval; the protocol for the present study was accordingly approved (SRC 11-062) before commencement.

Patient identification

Men were aged ≥45 years and had an initial diagnosis, symptoms or therapies indicating LUTS/BPH, between 1 January 2004 and 30 September 2011 (index date). Men with LUTS/BPH who had both storage and voiding symptoms were identified using two criteria: (1) initial record of LUTS diagnosis, voiding symptoms, post-micturition symptoms (based on Read code listsCitation15) or an α1-blocker prescription, with storage symptoms or an antimuscarinic prescription recorded during the following 12 months; or (2) initial record of storage symptoms or antimuscarinic prescription, plus LUTS diagnosis, voiding symptoms, post-micturition symptoms or α1-blocker prescription recorded during the following 12 months. Exclusion criteria included a record of prior 5-ARI prescription, prostate surgery, chronic prostatitis or urological pain syndrome, and α1-blocker use for hypertension (see Supplementary Information). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were strictly followed to ensure all men had both storage and voiding symptoms associated with LUTS/BPH, as opposed to other conditions.

Baseline demographics were collected before the index date (). Comorbidities (see Supplementary Information) were also collected, together with Townsend scores of social deprivationCitation16. Follow-up variables to be collected on and after the index date included urinary tract infection, skin irritation (excluding skin pathologies such as eczema and psoriasis), falls, fractures and depression.

Table 1. Baseline patient demographics and characteristics.

To ensure data quality, men had to be permanently registered with their GP and have at least 6 months’ quality-controlled data before their index date. Drug treatment patterns and resource use were observed until the date of the last THIN data collection, the patient’s transfer out of the practice, surgical intervention or prescription of 5-ARIs (see Supplementary Information).

Definitions of drug treatment patterns

The first prescribed α1-blocker or antimuscarinic was defined as the first agent of that class prescribed on or after the index date. Discontinuation of α1-blocker or antimuscarinic therapy was defined as no prescription for these drugs during the last 6 months’ follow-up. Men who received at least one antimuscarinic agent differing from their first prescribed antimuscarinic during follow-up were defined as having switched therapy. The total duration of antimuscarinic treatment equaled the sum of every antimuscarinic prescription throughout follow-up.

Quantification of healthcare resource use and data handling

Healthcare resource use was quantified using medical records of GP consultations, hospitalizations, referrals to secondary care, complications and tests related to urinary symptoms. Prescriptions for antimuscarinics, α1-blockers, incontinence pads, antidepressants and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim were also identified. Tests included cystometry, detrusor reflex testing, urinary flow rate and residual urinary volume. Secondary referrals were further quantified according to specialty: genitourinary, orthopedic, geriatric, psychiatry and dermatology. Resources used per patient-year were calculated. See Supplementary Information for further details of data handling.

Analyses

Categorical data were reported as numbers and percentages of men. Continuous data were presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Time to switch and discontinuation analyses started from the first prescribed antimuscarinics; data were illustrated as Kaplan–Meier curves. Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the probability of switching or discontinuing therapy according to the type of first prescribed therapy.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The study population included 8694 men with LUTS/BPH who had both storage and voiding symptoms, and a median age of 66.0 (IQR, 59.0–74.0) years (). The most common first presenting symptoms were increased daytime frequency (40.3%) and nocturia (37.8%). In addition, 8.2% reported urgency and 6.6% a voiding symptom (mostly slow or intermittent stream), while only 1.1% reported post-micturition symptoms.

Drug treatment patterns

Men were followed up for a median of 2.1 (IQR, 0.9–4.2) years. Most (7850; 90.3%) received an α1-blocker prescription during follow-up; of these, most (81.8%) received tamsulosin, while 16.4% received alfuzosin, and 10.8% received doxazosin (). Other α1-blockers were prescribed infrequently (<3%). Tamsulosin was the most common first prescribed α1-blocker (6033; 76.9%), followed by alfuzosin (876; 11.2%) and doxazosin (679; 8.7%). A total of 1160 men (14.8% of α1-blocker-treated men) received concomitant prescription of α1-blocker and antimuscarinic therapy (within 30 days of each other).

Table 2. Drug treatment between January 2004 and September 2011 for 8694 men with LUTS/BPH with both storage and voiding symptoms.

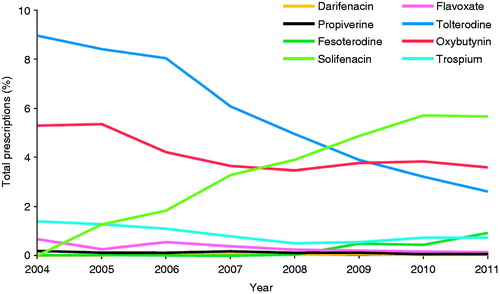

A quarter of the men (2167; 24.9%) received an antimuscarinic agent during follow-up; most common were tolterodine (41.0%), oxybutynin (37.2%) and solifenacin (35.7%). Other antimuscarinics were prescribed infrequently (<7%). Similarly, tolterodine (35.0%), oxybutynin (31.9%) and solifenacin (24.8%) were most often the first prescribed antimuscarinic. An analysis of antimuscarinic therapy prescriptions over time shows a trend of increased solifenacin use and decreased tolterodine use between 2004 and 2011; use of the other antimuscarinics remained generally consistent ().

Figure 1. Antimuscarinic therapy use according to each calendar year to the first prescribed antimuscarinica. aMen with at least one prescription for each antimuscarinic during each calendar year (n=8694). Percentages are calculated out of the number of men with the potential for a prescription during that specific year.

Overall, 3024 of 7850 (38.5%) men who received at least one α1-blocker subsequently discontinued (). Discontinuation rates varied depending on first prescribed therapy, ranging from 36.1% to 46.1% of men initially treated with doxazosin or terazosin, respectively. After adjusting for differences in baseline characteristics and follow-up, there was no evidence at the 5% level of any difference in discontinuation rates related to first prescribed α1-blocker therapy. There was, however, strong evidence (p < 0.001) linking α1-blocker discontinuation with age and history of BPH or hypertension.

Table 3. Changes to drug treatment for the α1-blockers.

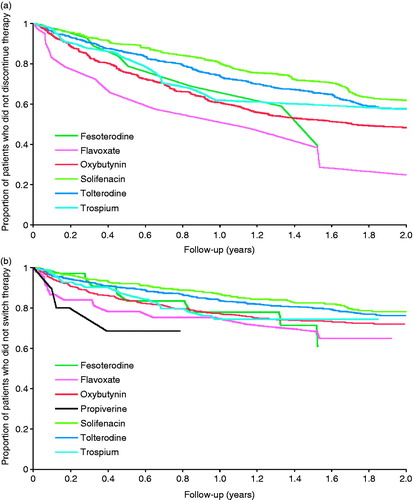

Of the 2167 men who received an antimuscarinic at any time, 53.0% discontinued during follow-up (). Discontinuation rates varied depending on first prescribed agent; of the three most commonly prescribed antimuscarinics, discontinuation was reported in 43.0%, 54.7% and 59.8% of men initially prescribed with solifenacin, oxybutynin and tolterodine, respectively. illustrates the time to antimuscarinic discontinuation according to first prescribed therapy. A switch from first prescribed antimuscarinic to another was reported for 22.0% of men who received an antimuscarinic. summarizes the time to first antimuscarinic switch according to that first prescribed. Switching rates varied across the different first therapies ().

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier curve for time to (a) discontinuation and (b) switch of antimuscarinic therapy according to the first prescribed antimuscarinic.

Table 4. Changes to drug treatment for the antimuscarinics.

After adjusting for differences in baseline characteristics and follow-up, there was evidence at the 5% level of differences in rates of discontinuation and switching according to first prescribed antimuscarinic. Men initially prescribed fesoterodine (HR = 0.54 [95% CI: 0.29–0.98]; p = 0.042) and solifenacin (HR = 0.77 [95% CI: 0.65–0.91]; p = 0.002) were less likely to discontinue antimuscarinic therapy compared to oxybutynin; there was no evidence at the 5% level of differences in rates for flavoxate, tolterodine or trospium (). Similarly, only men initially prescribed solifenacin (HR = 0.52 [95% CI: 0.40–0.67]; p < 0.001) and tolterodine (HR = 0.69 [95% CI: 0.56–0.86]; p = 0.001) were less likely to switch antimuscarinic therapy compared to oxybutynin.

Table 5. Hazard ratios (HRs), adjusted for factors with evidence of impact, for discontinuing or switching antimuscarinic therapy (n = 2087a).

The median duration of therapy for solifenacin was 90 days (IQR, 30–300; n = 773), whereas tolterodine and oxybutynin were prescribed for a median 56 days (IQRs, 28–224; n = 888, and 30–146; n = 806 respectively). Median durations of therapy for the least prescribed antimuscarinics ranged from 30 days (IQR, 28–60 days; n = 59) with flavoxate to 116 days (IQR, 43–238 days; n = 72) with fesoterodine.

Healthcare resource use

GP consultations related to urinary symptoms accounted for most resource use (5307.9 units per 1000 patient-years), followed by α1-blocker prescriptions (4230.1 per 1000 patient-years) and antidepressant prescriptions (1190.8 per 1000 patient-years) (). Nearly 60% of men were referred to secondary care. The most common specialty referrals were genitourinary and orthopedic (369.1 and 131.9 per 1000 patient-years, respectively). Hospitalizations and tests related to urinary symptoms were recorded infrequently (<4% of men).

Table 6. Healthcare resources consumed by the LUTS/BPH cohort (n = 8694).

Discussion

This study provides an overview of treatment patterns for men aged ≥45 years with LUTS/BPH who had both storage and voiding symptoms and who sought medical assistance from GPs in the UK between 2004 and 2011. A variety of α1-blocker and antimuscarinic therapies were prescribed during follow-up. One of the key findings was that, despite the large number of men who had LUTS/BPH with storage symptoms, most received α1-blocker therapy (∼90%), whilst a small proportion received an antimuscarinic (∼25%) or α1-blocker plus antimuscarinic therapy (∼15%) during the study.

Tamsulosin was the most commonly prescribed α1-blocker with nearly three-quarters of men receiving this agent at some time during follow-up. In contrast, the next most commonly prescribed agent, alfuzosin, was prescribed to only ∼15% of men. The high use of α1-blocker therapy in this study suggests that GPs in the UK follow expert recommendations for LUTSCitation1.

After adjustment for differences in patient characteristics, there was no evidence of differences in discontinuation rates across α1-blockers when used as initial drug therapy, which suggests few or no clinically relevant efficacy/tolerability differences between the various options. Few men were treated with α1-blockers other than tamsulosin or alfuzosin, so these observations should be interpreted with caution.

A quarter of the men received antimuscarinic therapy, with tolterodine and oxybutynin being most frequently prescribed first. Of the three most commonly prescribed antimuscarinics, solifenacin had the longest duration of therapy and the lowest switch and discontinuation rates. These findings were robust after adjustment for differences in baseline characteristics, which suggests a favorable efficacy/tolerability profile and greater likelihood of adherence for solifenacin. Solifenacin was also 23% less likely to be discontinued and 48% less likely to be switched than the reference drug, oxybutynin. These results are similar to those from another retrospective database study in 4833 patients with overactive bladder symptoms who received darifenacin, flavoxate, oxybutynin (extended or immediate release), propiverine, solifenacin, tolterodine (extended or immediate release) or trospiumCitation17. Solifenacin showed a mean persistence period of 187 days compared with 77–157 days for other agents. After 12 months, 35% of patients who were originally prescribed solifenacin were still taking the drug, compared with 14–28% for other agentsCitation17.

Compared with α1-blockers, a small proportion of men were treated with an antimuscarinic agent in this study. Similar results have been described in the EpiLUTS survey, which reported that only 11.2–17.6% of men with LUTS and both storage and voiding symptoms were prescribed medicationCitation18. Initial treatment with α1-blocker monotherapy may not adequately control symptoms in men with storage symptoms based on data which reported only 35% of men had improved symptoms with α1-blocker monotherapy, whilst α1-blocker plus antimuscarinic combination therapy improved symptoms in 73% of those men who did not initially respond to α1-blocker monotherapyCitation19. Combined, these data suggest that some men with storage symptoms may be inadequately treated in clinical practice, especially given these symptoms are particularly bothersomeCitation2 and can significantly affect HRQoLCitation6. Large randomized and controlled clinical studies have shown combination therapy with an α1-blocker and an antimuscarinic agent to be effective and well tolerated in men with moderate-to-severe LUTS and documented storage symptomsCitation8–13. Data for tolterodine have shown it to improve symptoms and HRQoL when added to existing α1-blocker treatmentCitation8,Citation11. Moreover, recent data from a double-blind phase III study in 1334 men with moderate-to-severe storage symptoms and voiding symptoms have shown a fixed-dose combination of solifenacin plus tamsulosin to improve storage symptoms and HRQoL compared with tamsulosin aloneCitation12. Combination therapy with an α1-blocker and an antimuscarinic is a recommended treatment option if symptom relief has been insufficient with the monotherapy of either drugCitation1,Citation4.

The greatest resource burden was the number of GP consultations related to urinary symptoms, with an average of five per patient/year. This is not surprising, as patients in the UK with LUTS are usually managed, at least initially, in primary careCitation1. More research is needed into the resource implications, e.g., use of different antimuscarinic therapies in this population, and the resource use and future benefits linked to combination therapy with α1-blockers and antimuscarinics.

Retrospective observational studies are limited by the quality and completeness of recorded data. Patients who did not seek medical attention from their GP would not have been captured by the database. Primary care records may be incomplete, especially when relating to secondary care (e.g., hospitalizations, referrals, tests), and details of use of over-the-counter products are not captured. Thus, healthcare resource consumption may be underestimated in our study. In addition, specific timings of treatment discontinuation could not be derived from the THIN database records. Combination treatment was therefore derived from concomitant prescription of α1-blockers and antimuscarinics within 30 days of each other.

Some of the α1-blockers included in the study have other indications such as hypertension. However, the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria should have minimized the effect of inappropriate selection. In addition, the patient sample was more affluent overall than the general UK population, which suggests that men from less affluent areas are less likely to seek medical attentionCitation20, although it may just reflect the distribution of the patients in the database.

Prescribing patterns and resource use may have changed between January 2004 and September 2011, particularly in response to the results of several large randomized studies of combination therapy reported during this period. However, the observational study design and collection of information from routine primary care sources provide valid, real-world evidence, applicable to the UK populationCitation14. Moreover, in the UK, GPs are routinely involved in the prescribing of antimuscarinics and α1-blockers, and our evaluation of drug treatment patterns is therefore likely to be reliable overall.

Future research should investigate differences in patient outcomes and resource use across different α1-blockers and antimuscarinic treatment strategies in routine clinical practice, and investigate the longer-term implications of combination therapy (particularly from a societal perspective) and initial treatment failure. There also remains a need for more research into the relative HRQoL benefits of different treatment strategies and drug therapies.

Conclusions

We provide valuable, representative and recent real-world data on drug treatment patterns and healthcare resource use in men who have LUTS/BPH with both storage and voiding symptoms. Among the most prescribed antimuscarinics, solifenacin has the lowest apparent switching and discontinuation rates. Additionally, only a small proportion of men presenting with both storage and voiding symptoms receive an antimuscarinic plus an α1-blocker. The results indicate that current practice by GPs in the UK may reflect a pattern of suboptimal treatment for some men. However, it is anticipated that this treatment pattern may change and more men will receive combination therapy on the basis of positive data from several recent phase III trials and recommendations in current treatment guidelines.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This study was funded by Astellas Pharma Global Development, Leiden, Netherlands.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Z.H. has disclosed that he is employed by Astellas Pharma Global Development. J.N. and I.A.O.O. have disclosed that they are employed by Astellas Pharma Europe Ltd. B.B. and M.J. have disclosed that they were employed by Cegedim Strategic Data Medical Research Ltd at the time of the study, and are now employed by AstraZeneca and OXON Epidemiology Ltd, respectively.

CMRO peer reviewers on this manuscript have received an honorarium from CMRO for their review work, but have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Christopher Dunn and Tyrone Daniel from Bioscript Medical, and was funded by Astellas Pharma Europe Ltd.

References

- National Clinical Guideline Centre. The Management of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Men. 2010. Available at: http://www.ncgc.ac.uk/Guidelines/Published/7 [Last accessed 30 July 2014]

- Roehrborn CG. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: an overview. Rev Urol 2005;7(Suppl 9):S3-14

- American Urological Association Guideline: Management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH). 2010. Available at: www.auanet.org/education/guidelines/benign-prostatic-hyperplasia.cfm [Last accessed 30 July 2014]

- Oelke M, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, et al. E guidelines on the management of male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), incl. benign prostatic obstruction (BPO). Available at: http://www.uroweb.org/gls/pdf/13_Male_LUTS_LR.pdf [Last accessed 30 July 2014]

- Ventura S, Oliver V, White CW, et al. Novel drug targets for the pharmacotherapy of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Br J Pharmacol 2011;163:891-907

- Coyne KS, Wein AJ, Tubaro A, et al. The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: evaluating the effect of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS. BJU Int 2009;103(Suppl 3):4-11

- Yokoyama T, Uematsu K, Watanabe T, et al. Naftopidil and propiverine hydrochloride for treatment of male lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia and concomitant overactive bladder: a prospective randomized controlled study. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2009;43:307-14

- Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Rovner ES, et al. Tolterodine and tamsulosin for treatment of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and overactive bladder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006;296:2319-28

- Lee KS, Choo MS, Kim DY, et al. Combination treatment with propiverine hydrochloride plus doxazosin controlled release gastrointestinal therapeutic system formulation for overactive bladder and coexisting benign prostatic obstruction: a prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter study. J Urol 2005;174(4 Pt 1):1334-8

- Kaplan SA, McCammon K, Fincher R, et al. Safety and tolerability of solifenacin add-on therapy to alpha-blocker treated men with residual urgency and frequency. J Urol 2009;182:2825-30

- Chapple C, Herschorn S, Abrams P, et al. Tolterodine treatment improves storage symptoms suggestive of overactive bladder in men treated with alpha-blockers. Eur Urol 2009;56:534-41

- van Kerrebroeck P, Chapple C, Drogendijk T, et al. Combination therapy with solifenacin and tamsulosin oral controlled absorption system in a single tablet for lower urinary tract symptoms in men: efficacy and safety results from the randomised controlled NEPTUNE trial. Eur Urol 2013;64:1003-12

- Van Kerrebroeck P, Haab F, Angulo JC, et al. Efficacy and safety of solifenacin plus tamsulosin OCAS in men with voiding and storage lower urinary tract symptoms: results from a phase 2, dose-finding study (SATURN). Eur Urol 2013;64:398-407

- Lewis JD, Schinnar R, Bilker WB, et al. Validation studies of The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database for pharmacoepidemiology research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:393-401

- Morant SV, Reilly K, Bloomfield GA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of overactive bladder and bladder outlet obstruction among men in general practice in the UK. Int J Clin Pract 2008;62:688-94

- Townsend P, Phillimore P, Beattie A. Health and Deprivation: Inequality in the North. London: Routledge, 1988

- Wagg A, Compion G, Fahey A, et al. Persistence with prescribed antimuscarinic therapy for overactive bladder: a UK experience. BJU Int 2012;110:1767-74

- Sexton CC, Coyne KS, Kopp ZS, et al. The overlap of storage, voiding and postmicturition symptoms and implications for treatment seeking in the USA, UK and Sweden: EpiLUTS. BJU Int 2009;103(Suppl 3):12-23

- Lee JY, Kim HW, Lee SJ, et al. Comparison of doxazosin with or without tolterodine in men with symptomatic bladder outlet obstruction and an overactive bladder. BJU Int 2004;94:817-20

- Blak BT, Thompson M, Dattani H, et al. Generalisability of The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database: demographics, chronic disease prevalence and mortality rates. Inform Prim Care 2011;19:251-5