Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of fentanyl 1 day patch in opioid-naïve patients with non-cancer chronic pain insufficiently relieved by non-opioid analgesics.

Research design and methods:

Two phase III placebo-controlled, double-blind, group-comparison, randomized withdrawal studies were conducted in patients with osteoarthritis and/or low back pain (N01 study) and post-herpetic neuralgia, complex regional pain syndrome, or chronic postoperative pain (N02) in Japan. Both studies consisted of period I (10–29 days of titration, fentanyl 12.5–50.0 µg/h) and period II (12 weeks double-blind).

Clinical trial registration:

N01, NCT01008618; N02, NCT01008553

Main outcome measures:

The primary endpoint was the number of days until study discontinuation due to insufficient pain relief in period II, and secondary endpoints included pain scored on visual analog scale (VAS), subject’s overall assessment, the number of rescue dose, brief pain inventory short form score, score on short-form 36-item health survey version 2.0, physician’s overall assessment, and assessment of adverse events.

Results:

Of the 218 (N01) and 258 (N02) subjects who entered period I, 150 and 163 subjects entered period II, respectively. In the N01 study, the between-group difference was significant in the VAS score (95% CI: 7.3 [1.1, 13.5] mm, P = 0.0215) but not in the primary endpoint (P = 0.0846, log-rank test). In the N02 study, both primary efficacy (P = 0.0003) and VAS (8.7 [2.4, 15.0] mm, P = 0.0071) results showed that fentanyl was more effective than placebo. The major adverse events were nervous system and gastrointestinal disorders typically associated with opioid analgesic use. The incidence of adverse events in the fentanyl group was 68.5% to 85.7%.

Conclusions:

Although the primary efficacy results showed significant effects of fentanyl in the N02 but not the N01 study, overall results showed that fentanyl 1 day patch is effective and well tolerated.

Keywords: :

Introduction

The fentanyl transdermal matrix 3 and 1 day system (hereinafter referred to as 3 and 1 day patch) developed by Janssen Pharmaceutical KK has been approved in Japan for the relief of (a) moderate to severe pain associated with various cancers and (b) moderate to severe chronic pain, only in opioid-tolerant patients but not opioid-naïve patients. The results of the company data of a market survey in Japan indicate that the fentanyl 1 day patch is preferable to the 3 day patch because of its compatibility with lifestyle habits. For this reason, we conducted two phase III placebo-controlled, double-blind, group-comparison, randomized withdrawal studies to investigate the safety and efficacy of fentanyl 1 day patch in opioid-naïve patients with non-cancer chronic pain insufficiently relieved by non-opioid therapy.

Patients and methods

Chronic pain can be classified into nociceptive or neuropathicCitation1. The opioid analgesics have been effective in treating nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain, and a combination of these two types. Therefore, two independent studies were designed: one included opioid-naïve subjects with nociceptive pain (osteoarthritis and/or low back pain; the JNS020-JPN-N01 study [N01 study]) and the other study included opioid-naïve subjects with neuropathic pain (post-herpetic neuralgia, complex regional pain syndrome [CRPS], or chronic postoperative pain; the JNS020-JPN-N02 study [N02 study]). Both studies used the same methods and had the same study design. The N01 study was conducted at 51 study sites in Japan from 14 January 2009 to 8 February 2010, and the N02 study was conducted at 66 sites in Japan from 26 December 2008 to 18 March 2010.

Male and female patients who were ≥20 years old and met all the following criteria were included: had osteoarthritis, low back pain, post-herpetic neuralgia, CRPS, or chronic postoperative pain for ≥12 weeks; had continuous (or non-continuous for medical reasons) non-opioid analgesic treatment at the highest approved dosage for ≥14 days, or had non-opioid analgesic treatment at a constant dosage which was lower than the highest approved dosage for ≥14 days; prior to the consent had a mean visual analog scale (VAS) pain score of ≥50 mm for 24 hrs; received no opioid analgesics except opioid used for acute pain such as surgery or post-surgery 30 days before consent, and codeine phosphate or dihydrocodeine phosphate used for other than as analgesic, such as antitussive 2 days before consent; and were able to be hospitalized for 4 days after the initiation of treatment in period I.

Of the eligible patients, those with mean pain VAS score ≥50 mm in the last 3 days of the pre-treatment period, treated with stable non-opioid analgesics in the last 3 days of the pre-treatment period, and requiring a continuous opioid analgesic, entered period I and received fentanyl 1 day patch for 10–29 days. Those patients who responded in period I with mean VAS score ≤45 mm in the last 3 days of period I, VAS score improvement of >15 mm in the last 3 days of period I compared to that in the last 3 days of pre-treatment period, constant fentanyl 1 day patch dosage for 3 days, and the number of times rescue medication used ≤2/day for the last 3 days, were further allowed to enter period II for 12 weeks.

Patients were excluded from the studies for any of the following reasons: low back pain with severe neuropathic pain; low back pain due to compression fractures; surgery that might have affected the evaluation; psychogenic pain; advanced respiratory dysfunction; asthma; bradyarrhythmia; liver dysfunction or renal dysfunction; brain tumor with increased intracranial pressure, impaired consciousness, coma and respiratory failure; neuropsychiatric disorders; alcohol, substance, narcotics dependence or abuse; malignancy; history of hypersensitivity to fentanyl and other analgesics; wounds in the skin region where application of the study drug was planned; and history of fentanyl 1 day patch treatment.

The institutional review board at each study site reviewed and approved the study protocol. This study was performed in compliance with Good Clinical Practice based on the Declaration of Helsinki and other applicable regulations. Prior to the start of the screening examination, signed informed consent was obtained from each patient. The N01 and N02 studies were registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01008618 and NCT01008553, respectively.

Study design

The fentanyl matrix system is a translucent, rectangular transdermal patch with a simple adhesive matrix design and has three dosage strengths (12.5, 25 and 50 µg/h), which are achieved by varying the surface area of the patch.

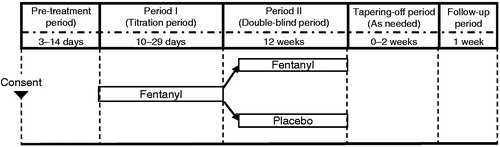

The study consisted of a pre-treatment period, period I (titration period, 10–29 days), period II (double-blind period, 12 weeks), tapering-off period, and follow-up period (). Subjects who entered period I were hospitalized and started treatment during their hospitalization. After being released from the hospitals, subjects were monitored daily on Days 5–7 in period I and Days 2–4 in period II by hospital visit or by phone. The detailed schedule of hospital visits is shown in . During period I, 1 day adhesive transdermal patches containing fentanyl were applied to the chest, abdomen, upper arm and thigh, and replaced every day, starting at a dosage of 12.5 µg/h for the first 2 days. The dosage was then increased in 12.5 µg/h steps up to a maximum of 50 µg/h based on the following criteria: the number of times rescue medication used ≥3/day; or VAS score >45 mm; or failure to achieve improvement of >15 mm compared to the mean VAS score in the last 3 days of the pre-treatment period. The dosage was not increased for 2 days after the first fentanyl administration and a dosage increase. One day after each dosage increase, its safety was assessed by clinical examination or over the phone. Subjects meeting the pre-defined criteria for entering period II were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive either fentanyl at the final dose administered during period I or a matching placebo for 12 weeks. Patients who were assigned to take placebo in the period II were allowed to take fentanyl under blind for opioid tapering. Administration of a fast-acting oral morphine formulation (morphine hydrochloride at a dose of 5 mg per fentanyl 12.5 μg/h) was allowed as a rescue treatment for breakthrough pain during period II. Opioid withdrawal symptoms were monitored over 0–2 weeks of the tapering-off period.

Table 1. Schedule (N01 and N02 studies).

Study endpoints and assessments

The primary endpoint was the number of days from the day of study drug initiation in period II to withdrawal because of insufficient analgesic efficacy. The discontinuation criteria included the worsening of the mean VAS score by >15 mm for three consecutive days compared to that in the last 3 days of period I; the number of times rescue medication used ≥3/day for five or more days after the initiation of period II; the mean number of times rescue medication used for three consecutive days increased by >1/day compared to that in the last 3 days of period I; a request for study discontinuation due to insufficient analgesia; and an increase in study drug dosage.

The average intensity of daily pain was assessed by each subject on a 0–100 mm VASCitation2 and used as a secondary endpoint. Other secondary endpoints included the subject’s overall assessment, the number of rescue doses per day, brief pain inventory short form (BPI-sf)Citation3 score, short-form 36-item health survey version 2.0 (SF-36v2)Citation4 score, physician’s overall assessment, and adverse events (AEs). The schedules of these tests are summarized in .

The subject’s overall assessment was used to rate the degree of treatment satisfaction for pain (very satisfied, satisfied, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, dissatisfied, and very dissatisfied) by subjects. The number of rescue doses per day was determined from subjects’ daily records. Self-reported pain intensity was rated using the BPI-sf with scores ranging from 0 to 10 (no pain to the worst pain ever experienced). The SF-36 (which consists of eight scales, namely vitality, physical functioning, bodily pain, general health perceptions, physical role functioning, emotional role functioning, social role functioning, and mental health) was used to assess health disability, with lower score indicating greater disability. The physician’s overall assessment was used to rate the study drug as either ‘effective’ or ‘ineffective’ by investigators.

AEs were recorded throughout the duration of the studies. Other assessments included urinalysis, hematological and biochemical tests, vital signs (including body temperature, respiratory rate, sitting blood pressure, and pulse rate), electrocardiogram (ECG), questionnaire survey of opioid withdrawal symptomsCitation5 and questionnaire survey of dependency. The schedules of these tests are summarized in .

Statistical analyses

Based on the results of past overseas studiesCitation6,Citation7, percentage of patients unable to obtain sufficient pain relief 12 weeks after the start of treatment in period II was set at 12.0% in the fentanyl group (both N01 and N02), and 40.0% (N01) and 37.0% (N02) in the placebo group. With the two-sided significance level set at 5% and power ≥90%, the number of subjects required was estimated to be 120 in N01 and 136 in N02. Assuming that 10% of subjects would withdraw for reasons other than lack of analgesic effect during period II, we estimated that 67 and 76 subjects per group, as well as 134 and 152 subjects per study were needed for randomization into the N01 and N02 studies, respectively. Since 62.9% (205/326) subjects and 57.0% (143/251) subjects entered the double-blind period in the previous overseas studies, a total of 223 subjects (N01) and 254 subjects (N02) were planned to enter period I of the present study.

In the N01 and N02 studies, the efficacy analyses were performed in the full analysis set (FAS) 1 (i.e., all subjects with efficacy data in period I) and the FAS (i.e., all subjects received at least one study drug with efficacy data in period II). The per protocol set (PPS) was defined as the FAS excluding subjects with one or more major protocol deviations that might have affected the efficacy evaluation. The primary analysis set was FAS. The log-rank test was applied to primary analysis with two-sided alpha-level of 5%. The Kaplan–Meier method, log-rank test (two-tailed), and Cox regression were applied to the primary endpoint. The sensitivity analyses were performed by comparing the analysis results between the FAS and PPS population. For the analysis of secondary endpoint VAS score, descriptive statistics were used to assess the actual VAS score and its change at each time point. With baseline values as covariates and the drug group as factor, analysis of covariance was conducted to estimate the change in pain VAS during period II. Two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated followed by the estimation of a between-group difference. For the analysis of subjects’ overall assessment, a proportion of patients and 95% CI in each category at each time point were obtained.

For the safety analyses, all subjects who entered period I were defined as safety population 1 (SP1) and those who entered period II were defined as safety population 2 (SP2). In SP1 AEs occurring during period I were included in the analyses for subjects who entered period II, and those occurring during period I, the tapering-off period and the follow-up period were included for subjects who did not enter period II. In SP2 AEs occurring in period II, the tapering-off period and the follow-up period were included in the analyses. AEs were coded by system organ class (SOC) and preferred term using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 13.0. Adverse reactions (ARs) were defined as study-drug-related AEs.

Results

Subjects with nociceptive pain (osteoarthritis and/or low back pain) (N01)

Subjects’ disposition and baseline characteristics

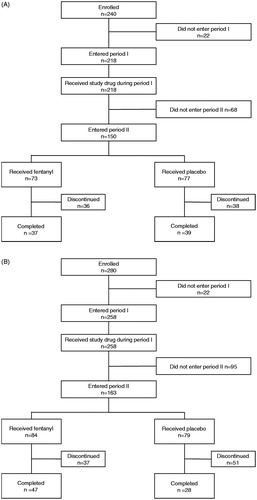

Subjects’ disposition is shown in . Of the subjects who entered period I, 68/218 (31.2%) subjects discontinued the treatment during period I. The major reasons for discontinuation included AEs (48.5%, 33/68 subjects) and unmet criteria for entering period II (29.4%, 20/68 subjects). In these 20 subjects, 18 subjects had mean VAS score >45 mm in the last 3 days of period I. Among the subjects who entered period II, 36/73 (49.3%) subjects in the fentanyl group and 38/77 (49.4%) subjects in the placebo group discontinued the study mainly because the mean VAS score for three consecutive days worsened by >15 mm compared to the end of period I (21/36 [58.3%] subjects in the fentanyl group and 29/38 [76.3%] subjects in the placebo group). In total 76 subjects completed period II (37/73 [50.7%] subjects in the fentanyl group and 39/77 [50.6%] subjects in the placebo group). There were no significant between-group differences in demographic and baseline characteristics ().

Table 2. Patients’ baseline characteristics.

The duration and the total amount of study drugs in the N01 study are shown in . At the end of period I, fentanyl had been administered to 80/218 (36.7%) subjects at 12.5 μg/h, 75/218 (34.4%) subjects at 25 μg/h, 35/218 (16.1%) subjects at 37.5 μg/h, and 28/218 (12.8%) subjects at 50 μg/h.

Table 3. Duration and total amount of treatment with study drugs (N01 and N02 studies).

Primary efficacy analysis

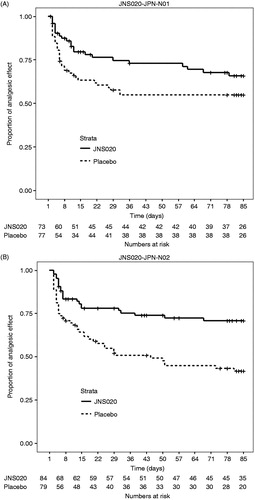

By using the Kaplan–Meier survival method, the time to discontinuation caused by insufficient pain relief was longer in the fentanyl group (), but the difference between the treatment groups was not significant (log-rank test, P = 0.0846). The same analysis in the PPS showed a similar result (P = 0.0880). The hazard ratio adjusted by disease was 0.612 (95% CI: [0.357, 1.049]; Wald test, P = 0.0741).

Secondary efficacy analyses

The mean (SD) change in the VAS score between the last 3 days of period I and those of period II was 0.2 (18.21) mm in the fentanyl group and −6.9 (20.84) mm in the placebo group. The results further showed that fentanyl significantly suppressed the worsening of the pain VAS in the fentanyl group compared to the placebo group (least square mean between-group difference [95% CI]: 7.3 [1.1, 13.5] mm, P = 0.0215). The results of other secondary endpoints are summarized in .

Table 4. Summary of secondary efficacy results (N01 study).

Safety analyses

The incidences of AEs are shown in . In period I, the incidence of serious AEs was 5.5% (12/218 subjects). The incidence of each serious AE was 0.5% (1/218) except for nausea which was 1.4% (3/218). Most AEs were mild (62.4%) or moderate (17.0%). One subject died of interstitial lung disease during period I, which was determined by the investigator not to be related to the fentanyl 1 day patch. AEs leading to discontinuation of the study occurred in 19.3% (42/218) of subjects. Among the AEs that resulted in discontinuation of the study, those occurring in ≥2 subjects were nausea (8.3%, 18/218 subjects), dizziness and vomiting (3.2%, 7/218 each), somnolence (2.3%, 5/218), dyspnea (1.4%, 3/218), and hallucination, abdominal discomfort and constipation (0.9%, 2/218 each). The incidence of ARs was 78.0% (480 events in 170/218 subjects).

Table 5. Incidence of adverse events reported by ≥5% of subjects during period I (SP1) or period II (SP2) in the N01 study.

In period II, the incidence of AEs was higher in the fentanyl group (68.5%, 113 events in 50/73 subjects) than in the placebo group (46.8%, 98 events in 36/77 subjects) (). Serious AEs occurred in 4.1% (3/73; pneumonia aspiration, gastric ulcer and pain in 1.4%, 1 subject each) of subjects in the fentanyl group and 2.6% (2/77; anxiety and malaise in 1.3%, 1 subject each) of subjects in the placebo group. AEs in both groups were generally mild or moderate in severity. The severe AEs reported in the fentanyl group were gastric ulcer and pain (1.4%, 1/73 subject each). No severe AEs were found in the placebo group. No death was reported in period II. AEs leading to discontinuation of the study occurred in 6.8% (5/73; dyspnea in 2.7%, 2 subjects, and somnolence, nausea, hematuria and urinary retention in 1.4%, 1 subject each) of subjects in the fentanyl group and 1.3% (1/77; anxiety) of subjects in the placebo group. The incidence of ARs was higher in the fentanyl group than in the placebo group (52.1%, 38/73 subjects vs. 36.4%, 28/77).

One subject at the end of period I and 3 subjects at the end of period II in the placebo group had opioid withdrawal symptom scores of 5–12 in questionnaire survey. Except for this finding, no clinically meaningful events were reported throughout periods I and II.

Subjects with neuropathic pain (post-herpetic neuralgia, CRPS or chronic postoperative pain) (N02)

Subjects’ disposition and baseline characteristics

Subjects’ disposition is shown in . Of the subjects who entered period I, 95/280 (33.9%) subjects discontinued treatment during period I. The major reasons for discontinuation included unmet criteria for the transition to period II (52.6%, 50/95 subjects) and AEs (34.7%, 33/95 subjects). In these 50 subjects, the mean VAS score for 3 days was >45 mm in 48/50 (96.0%) subjects during period I, and 26/50 (52.0%) subjects did not improve by >15 mm during period I when compared to the data in the last 3 days of the pre-treatment period. Among the subjects who entered period II, 37/84 (44.0%) subjects in the fentanyl group and 51/79 (64.6%) subjects in the placebo group discontinued the study. The major reasons for discontinuation were the mean VAS score in three consecutive days in period II worsening by >15 mm compared to those in the last 3 days of period I (18/37 [48.6%] subjects in the fentanyl group and 35/51 [68.6%] subjects in the placebo group), followed by AEs (14/37 [37.8%] subjects in the fentanyl group and 4/51 [7.8%] subjects in the placebo group). In total 75 subjects completed period II (47/84 (56.0%) subjects in the fentanyl group and 28/79 (35.4%) subjects in the placebo group). There were no significant between-group differences in demographic and baseline characteristics ().

The duration and the total amount of study drugs in the N02 study are shown in . At the end of period I, fentanyl had been administered to 70/258 (27.1%) subjects at 12.5 μg/h, 83/258 (32.2%) subjects at 25 μg/h, 48/258 (18.6%) subjects at 37.5 μg/h, and 57/258 (22.1%) subjects at 50 μg/h.

Primary efficacy analysis

By using the Kaplan–Meier survival method, the time to discontinuation caused by insufficient pain relief was significantly longer in the fentanyl group () (log-rank test, P = 0.0003). The same analysis conducted in the PPS showed a similar result (P = 0.0005). The hazard ratio adjusted by disease was 0.462 (95% CI: [0.276, 0.772]; Wald test, P = 0.0032).

Secondary efficacy analyses

A change in the VAS score between the last 3 days of period I and those of period II was 0.3 (21.28) mm in the fentanyl group and −9.6 (20.45) mm in the placebo group. The results further showed that fentanyl significantly suppressed the worsening of pain VAS in the fentanyl group compared to the placebo group (least square mean between-group difference [95% CI]; 8.7 [2.4, 15.0] mm, P = 0.0071). The results of other secondary endpoints are shown in .

Table 6. Summary of secondary efficacy results (N02 study).

Safety analyses

The incidences of AEs are shown in . In period I, serious AEs occurred in 5.0% (13/258) of subjects. The incidence of each serious AE was 0.4% (1/258) except for dizziness which was 0.8% (2/258 subjects). Most AEs were mild (65.5%) or moderate (22.1%). AEs leading to discontinuation of the study occurred in 15.1% (39/258) of subjects. Among the AEs that resulted in the discontinuation of study, those occurred in ≥3 subjects were nausea (5.0%, 13/258 subjects), somnolence (3.1%, 8/258), dizziness (2.7%, 7/258), and constipation and malaise (1.2%, 3/258 each). The incidence of ARs was 86.4% (742 events in 223/258 subjects).

Table 7. Incidence of adverse events reported by ≥5% of subjects during period I (SP1) or period II (SP2) in the N02 study.

In period II, the incidence of AEs was higher in the fentanyl group (85.7%, 188 events in 72/84 subjects) than in the placebo group (70.9%, 123 events in 56/79 subjects) (). Serious AEs were reported in 9.5% (8/84; pancreatic carcinoma, arteriosclerosis obliterans, gastric ulcer hemorrhage, nausea, urinary retention, renal impairment, asthenia and muscle rupture in 1.2%, 1 subject each) of subjects in the fentanyl group, and in 5.1% (4/79; pneumonia, drug interaction, drug withdrawal syndrome and fall in 1.3%, 1 subject each) of subjects in the placebo group. AEs in both groups were generally mild or moderate in severity. AEs leading to discontinuation of the study occurred in 13.1% (11/84; pancreatic carcinoma, anxiety, depression, arteriosclerosis obliterans, chronic bronchitis, nausea, urinary retention, renal impairment, asthenia, malaise and blood alkaline phosphatase increased in 1.2%, 1 subject each) of subjects in the fentanyl group and 3.8% (3/79; dizziness, myalgia, drug interaction and drug withdrawal syndrome in 1.3%, 1 subject each) of subjects in the placebo group. The incidence of ARs was higher in the fentanyl group (69.0%, 58/84 subjects vs. 48.1%, 38/79 subjects in the placebo group). Throughout periods I and II, no death occurred and no clinically meaningful events were reported.

Discussion

In the present studies, the efficacy and safety of fentanyl 1 day patch were evaluated in opioid-naïve patients with non-cancer chronic pain who could not obtain sufficient pain relief by non-opioid analgesics. The difference in the primary efficacy endpoint, the number of days from the initiation of study drug administration in period II to discontinuation due to insufficient pain relief, between the fentanyl 1 day patch and placebo groups was not significant in patients with nociceptive pain (N01 study) (log-rank test, P = 0.0846). Although log-rank test failed to show a statistically significant difference in efficacy between the fentanyl 1 day patch and placebo for the primary analysis, the point estimate of the hazard ratios suggests that a difference in the therapeutics showed a certain degree of effectiveness in patients with nociceptive pain. The efficacy results of study N02 showed that the difference in the primary efficacy endpoint between the fentanyl 1 day patch and placebo groups was significant in patients with neuropathic pain (N02 study) (P = 0.0003), thus suggesting its effectiveness in opioid-naïve subjects with neuropathic pain.

The results of the secondary efficacy endpoint, pain VAS score analysis indicated that the fentanyl 1 day patch was effective in relieving pain for a significantly longer duration in patients with nociceptive and neuropathic pain. Taken together with the results of other secondary efficacy endpoints, the overall efficacy results indicate that the fentanyl 1 day patch is effective and resulted in greater treatment satisfaction than the placebo in opioid-naïve patients with nociceptive and neuropathic pain.

The present safety analyses showed that nervous system and gastrointestinal disorders were the major and most common AEs and ARs of fentanyl 1 day patch treatment. These AEs and ARs have been reported to be typical opioid-related symptomsCitation8–12, and no new safety issue specifically related to fentanyl or its patch formulation was raised. Collectively, the present and past results indicate that the fentanyl 1 day patch is safe and well tolerated in opioid-naïve patients with non-cancer chronic pain.

The present studies had a withdrawal design instead of a randomized design and were our first withdrawal studies. The reasons are: (1) Lemmens and colleagues have proposed the use of a randomized withdrawal study design to evaluate the efficacy of analgesics for chronic pain reliefCitation13; (2) the E10 guideline of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use states that the randomized withdrawal design can be used to investigate study drugs that suppress symptoms and signs (such as chronic pain, hypertension, and angina pectoris) and used when it is difficult to treat patients with placebo for a prolonged period. However, it should be noted that considering the favorable analgesic effects of the fentanyl 1 day patch shown in period I, a conventional placebo-controlled randomized study could have demonstrated the efficacy of this drug even in a smaller sample size.

In summary, these two studies are the first clinical trials to demonstrate that the fentanyl 1 day patch is effective and well tolerated in opioid-naïve patients with nociceptive and neuropathic pain as well as in patients who switch to fentanyl 1 day patch from other opioidsCitation12 but it has not been submitted for use in opioid-naïve patients in Japan for a Japan-specific regulatory reason.

Conclusion

The present studies show that fentanyl 1 day patch is effective and well tolerated in opioid-naïve patients with non-cancer nociceptive pain and neuropathic pain. However, it should be noted that the use of fentanyl transdermal patches, whether applied as 3 day or 1 day patches, have been approved in Japan for relief of (a) moderate to severe pain associated with various cancers and (b) moderate to severe chronic pain, both only in opioid-tolerant patients.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Editorial support was funded by Janssen Pharmaceutical KK.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

T.A., Y.K., Y.U., Y.T., and K.I. have disclosed that they are employees of Janssen Pharmaceutical KK.

CMRO peer reviewers have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by medical writer Chiaki Fukuhara PhD, and coordination and editorial support were provided by Kenichiro Tsutsumi, funded by Janssen Pharmaceutical KK.

References

- Suzuki T. Opioid therapy for non-cancer chronic pain. Treatment with weak opioid and codeine (in Japanese). J Pain Clin Med 2003;3:199-203

- Knop C, Oeser M, Bastian L, et al. Development and validation of the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) Spine Score. Unfallchirurg 2001;104:488-97

- Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1994;23:129-38

- McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care 1994;32:40-66

- Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs 2003;35:253-9

- Katz N, Rauck R, Ahdieh H, et al. A 12-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial assessing the safety and efficacy of oxymorphone extended release for opioid-naive patients with chronic low back pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;23:117-28

- Hale ME, Ahdieh H, Ma T, et al. Efficacy and safety of OPANA ER (oxymorphone extended release) for relief of moderate to severe chronic low back pain in opioid-experienced patients: a 12-week randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Pain 2007;8:175-84

- Miyazaki T, Hanaoka K, Namiki A, et al. Clinical trial of Durotep MT patch in patients with chronic non-cancer pain I – 4 weeks and long-term 52 weeks study (in Japanese). J New Rem Clin 2010;59:157-80

- Miyazaki T, Hanaoka K, Ogawa S, et al. Clinical trial of Durotep MT patch in patients with chronic non-cancer pain II – 4 weeks study with the pain control achievement rate as the primary endpoint (in Japanese). J New Rem Clin 2010;59:181-200

- Hanaoka K, Yoshimura T, Tomioka T, Sakata H. Clinical study of one-day fentanyl patch in patients with cancer pain – evaluation of the efficacy and safety in relation to treatment switch from opioid analgesic therapy (in Japanese). Masui 2011;60:147-56

- Hanaoka K, Yoshimura T, Tomioka T, Sakata H. Double-blind parallel-group dose-titration study comparing a fentanyl-containing patch formulated for 1-day application for the treatment of cancer pain with Durotep MT patch (in Japanese). Masui 2011;60:157-67

- Imanaka K, Yoshimura T, Shikinami K, et al. A phase 3 study of JNS020QD (fentanyl transdermal matrix 1-day system) in patients with chronic noncancer pain: efficacy and safety at switching from opioid analgesics in long-term use (in Japanese). Pain Clinic 2014;35:781-90

- Lemmens HJ, Wada DR, Munera C, et al. Enriched analgesic efficacy studies: an assessment by clinical trial simulation. Contemp Clin Trials 2006;27:165-73