Abstract

Although there is some awareness of how women in infertility treatment have suffered physically and psychologically, it is a little known fact that there is a limit to the “cures” that can be achieved even with assisted reproductive technologies. Here, I describe how the existence of ART affects women's decision making about their lives. Through life histories of women who underwent infertility treatment, I explore the factors which cause their suffering and conflict—that they cannot give up on having children even though they want to give up—as follows: (1) The models of their ideal family which have been formed throughout their lives is ‘ordinary’ family; (2) they experienced the alienation from their own bodies in infertility treatment; (3) they are afraid that they deviate from the community norm because of infertility; (4) their narrative shows their suffering from infertility is caused by tense relationship in family and community. These factors make women in infertility belittle themselves. Through their life histories, I conclude that they need to be empowered if they want to akirameru (give up) having children after prolonged infertility treatment. To paraphrase, a woman who suffers from infertility and infertility treatment is empowered when she becomes unafraid to deviated from cultural norms.

Abstract

要約

女性が不妊治療によって身体的にも精神的にも苦しむことはかなり知られ るようになったが、たとえ先端的な生殖補助医療技術(ART) を用いても、子 どもを得られないことが少なくないことはあまり知られていない。本稿で は、不妊治療を受けた女性のライフ・ヒストリーを通して、成功率が高く はなく、身体的にも精神的にも苦痛を伴う不妊治療を続ける理由と、不妊 治療の失敗を繰り返したときに、子どもをもつことを「あきらめたいけど あきらめきれない」という葛藤の要因を分析した。その結果、(1)彼女たち の人生経験によって形成された理想の家族が「普通」の家族であること、 (2)不妊治療によって自己身体から疎外されること、(3)不妊によって文化 的な規範から逸脱することを恐れていること、そして、(4)不妊と不妊治療 の苦しみの多くが人間関係における緊張として語られることを指摘した。 以上のことから、不妊と不妊治療によって自己評価が低下している状態で は、「あきらめる」には、エンパワーメントが必要であることを述べた。 ここでいうエンパワーメントとは、自分が「普通」だと考える規範からの 逸脱をおそれなくなることとも言い換えることができる。

キーワード: 不妊、医療化、あきらめる、エンパワーメント、ライフ・ ヒストリー

1 Introduction

We welcome more than 18,000 babies per year, thanks to in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)—about 1.5% of all babies born annually in Japan. The cumulative number of people who were born through IVF and/or ICSI since 1983 has reached more than 150,000. Footnote1

The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research in Japan reported their estimated numbers related to infertility in 2005. In the report, a quarter of childless couples had undergone infertility treatments; thus, the ratio is about 13% among all couples.

Although there is some awareness of how women in infertility treatment suffer physically and psychologically, it is a little known fact to people in general that there is a limit to the “cures” that can be achieved even with advanced medical technologies. A self-support group for infertility in Japan reported the cumulative result of treatments for infertility detected by a questionnaire survey of the group's 875 members: about 30% of respondents gave birth and 18% were continuing treatment, but 34% answered that they had discontinued treatment without having children (CitationFinrrage-no-kai 2000; 54–57). However, the belief that medical technologies can solve the problem of infertility is strongly held not only by patients and the general public but also by the gynecologists who promote assisted reproductive technologies (CitationTsuge 1999).

Since the first baby by IVF was reported in 1978 in the UK, there has been controversy related to new reproductive technologies for infertility. First, ethical, legal issues as well as technological issues regarding new reproductive technologies for infertility were argued (e.g., CitationWarnock 1985). They argued about: “when human life begins”, “who has the right to access IVF-ET and other treatments”, “who should be determined as a legal father or a legal mother of a baby who is born through surrogate motherhood”, and so on. Unlike these arguments, feminists asked critical questions regarding new reproductive technologies in the context of patriarchy, pro-natalism, the dominance of the medical professions, and disparities of class, race, and gender (e.g., CitationCorea 1985; CitationArditti et al. 1984; CitationKlein 1989). Then several excellent anthropological or sociological works about infertility in different cultures appeared (e.g., CitationInhorn 1996, CitationBecker 1997, 2000). These approaches to infertility portray the variations and universality of relationships between wife and husband, parents and children, and doctor and patient from a global perspective. Anthropologists and Sociologists of Medicine examine medicalisation from critical points of view, calling it variously a form of social control (CitationZola 1972) and social and cultural “iatrogenesis” (CitationIllich 1975). The new concept of “biomedicalization” Footnote2 has also been defined as a way of understanding the phenomenon of everyday life in present-day society (CitationClarke et al. 2003). Lately, remarkable multidisciplinary works on infertility and infertility treatment from integrated STS and feminist points of view have been published (CitationThompson 2005).

There are some good discussions regarding why people seek infertility treatment. The causes and effects of the medicalisation of infertility are also considered (CitationBecker and Nachtigall 1992). My question is why people cannot stop their treatment and cannot give up on having children even though they want to give up. I believe that it is also an aspect of the STS (science, technology, and society) studies to consider the interrelations between human beings and medical technologies. Footnote3

2 Research Methods

From 1991 to 1993, I conducted semi-structured, face-to-face interviews with 35 gynecologists involved in infertility treatment in Japan for the purpose of analyzing the factors which stimulate gynecologists to use new reproductive technologies in infertility treatment. I point out what kind of medical or ethical standards gynecologists have and how they thought about their activities in infertility treatment (CitationTsuge 1999).

Simultaneously, I also conducted semi-structured, face-to-face interviews with 11 women who have experienced infertility treatment in order to understand why many women underwent infertility treatment in spite of its risks, low success rate, and high cost. From the study, I describe what sort of motivation and conditions are applied by the patients in choosing medical facilities and methods of infertility treatment and how those relate to Japanese social and cultural factors.

Afterwards, because nine of the 11 agreed to the continuation of this survey, I interviewed them several times up until 1999. I could not contact one woman for follow-up interview. Another declined to participate in follow-up interview because she badly wanted to forget her experience of failed infertility treatment. I adopted the unstructured, in-depth interview, that is, interviewees talk to me about whatever they want, not only their experiences of infertility but also going into depth about their whole life.

Analyzing the data using the grounded theory approach, I described how the social view of infertility stigmatizes involuntarily childless women and men. I also discuss the fact that the developing medical technologies in infertility treatment cause women conflict because they cannot give up on having children even though they want to give up (CitationTsuge 2000).

Here, I draw their life history by the anthropological methodology from interview data, adding their letters, notes of phone calls, and so on with their consent. These interviewees have been deeply considering the meaning of their experiences in infertility, which is the primary reason I want to show their life histories, including their narratives. Next, I examine how women have faced their infertility. Then I analyze the reasons why they could not easily discontinue their treatments, while, in contrast, they easily began to take infertility treatment.

3 Interviewees

Concerning the interviewees, one of the nine was born in the 1940s, four in the 1950s, and four in the 1960s. Three of them live in metropolitan areas, three in cities, two in suburbs, and one in a small town. Related to education, one graduated high school, three finished vocational school after graduating from high school, three graduated junior college, and two graduated from university. Three of them are housewives, four are part-time workers, and two are full-time workers.

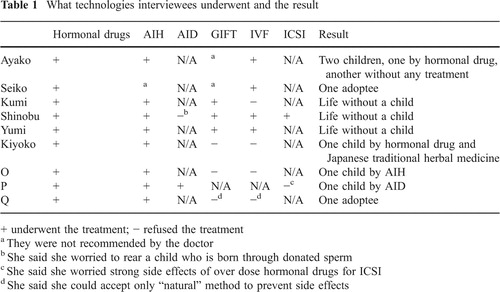

The diagnosed causes of infertility were diverse. There were four cases in which mainly the woman was seen as being the cause of infertility, two in which mainly the man was, two in which both partners were, and one case in which the cause of the infertility was unknown (idiopathic infertility). To describe the methods of infertility treatment briefly, by 1999, all of the nine had taken drugs which stimulated ovulation, eight of them had had artificial insemination by husband sperm (AIH), one artificial insemination by donor sperm (AID), three gametes intra-fallopian tube transfer (GIFT), four IVF, and one ICSI. As a result of these treatments, three women each have one child, one has two children, two each have an adoptee, and three are childless (see ). Using donated eggs and embryos as well as surrogate motherhood are regulated by Japanese Society of Obstetrics and Gynecologists.

First of all, I would like to show you one of the nine women's stories in detail, focusing on her experiences and feelings about infertility related to her life events. I will use pseudonyms for all the interviewees. Then I also show you five women's life histories related to infertility. Three of them are childless, one has a son, and another has an adoptee. The reason I chose the six women is that in the interviews they focused on and described in detail their conflict between giving up and not giving up.

For reasons of space, I cannot tell all nine life histories here. I first describe Ayako's case because I think it shows the ‘average’ life course of Japanese women born in the 1960s.

4 Ayako's Life History Focusing on Infertility

I first interviewed Ayako in 1993, a few months after her first IVF trial. With tears in her eyes, she explained her experience of infertility and infertility treatment. She was born in a nuclear family in a suburban area of a big city in 1965. She has an elder brother and a younger sister. After high school, she worked as a clerk for 7 years at a company. She got married at the age of 24 with her coworker. She quit her full-time job because she was exhausted by her busy job and hard commutes.

She went to see a gynecologist because of irregular bleeding, and then she was diagnosed with endometriosis. After a year of treatment, she started infertility treatment on her doctor's advice. Taking an oral hormonal drug and having the timing of ovulation checked by ultrasound repeatedly, she felt frustrated, so she transferred to an infertility specialist's clinic. She had AIH four times there, but could not get pregnant. The specialist recommended that she have IVF. She worried about the risks and high costs of IVF, but decided to have IVF after she talked about it with her husband. He appeared positive about IVF, in contrast to her. Since she suffered from intense dejection at the failure of every treatment cycle over more than 2 years, she wanted to get pregnant as early as possible, even though she would have to undergo IVF. She was 27 years old when she decided to have IVF.

Here, I would like to look back at this couple's environment. Her husband was born in an extended family in a rural village in the 1960s. He is the eldest son with an elder sister and a younger brother. After he graduated from university, he got a job at the company where Ayako worked. Then they married. Since his father had died before he got married, he has been conscious of his responsibility to the extended family, especially his mother and grandmother, and of trying to continue the family line. His mother treats Ayako as a daughter-in-law in the “old-fashioned” way and wishes to live with her at her house when the expected grandchildren arrive. However, Ayako is not familiar with the “old-fashioned” family system and cannot stand the attitude her mother-in-law has toward her. In particular, she was upset by being told that she should have a child soon. She explained that her husband usually felt caught between his wife's and his mother's complaints.

Ayako was also tired of being asked whether she has children not only by relatives but also other people. She was also shocked to hear from her mother-in-law that the younger son's wife had gotten pregnant. She had not been told that by the couple, even though she is close to the wife. Previously, Ayako had suggested a good clinic for infertility treatment at her sister-in-law's request, and then they had confided in each other about their distress. Ayako felt that she had been left behind and marginalized by her sister-in-law. Furthermore, she felt that she was pitied by the couple, which was why they felt that they could not tell her about their pregnancy. The event pushed Ayako and her husband toward infertility treatment with more enthusiasm.

Going back to Ayako's infertility treatment, she told her parents but not her mother-in-law about IVF as well as the earlier infertility treatment. Her parents were so surprised and worried that they gave her a lot of expensive supplements to maintain her health. She explained that the reason she and her husband did not tell his mother about IVF was that they did not want her to worry. But it is clear that Ayako and her husband worried about prejudice and stigma due to her infertility. Ayako is aware of her expected role to bear atotsugi (an heir to her husband's family).

Regarding the IVF experience, she emphasized her tremendous physical pain during the process, including during egg retrieval and embryo transfer, because of intra-pelvic adhesion from her endometriosis. In addition, she had considerable fear during the procedure. After the embryo transfer, she also suffered ovarian hyper stimulation syndrome.

Although her basal body temperature (B.B.T.) was in the high-temperature phase, she had menses-like bleeding 1 day before the pregnancy test at the clinic. Early on the morning that she was going to see the doctor, she awoke every hour and took her B.B.T. to make sure she was still in the high-temperature phase. Although her menses had begun that morning, she still kept hoping she was pregnant. However, the doctor briefly told her of the failure. She could not stand to cry in front of him and could not remember how she got home.

Her husband consoled her gently and encouraged her to try again. She was grateful for her husband's support and encouragement of her treatment but felt his high expectation that she would get pregnant to be a burden. She felt sorry for her husband not being able to have a child and for her parents and mother-in-law not being able to show off their grandchildren; producing grandchildren is not only her duty but also a tribute to her affection for them.

A month later, she underwent the second embryo transfer using frozen embryos. She had unexpectedly strong pain during the procedure. After a few weeks, she was told that this second attempt had also failed. The doctor comforted her. Then she talked to her husband about stopping IVF because of the terrible pain. He agreed with her. Thus, she told her doctor that she could not stand the awful pain, so she wanted to stop the IVF and only treat the endometriosis.

At the second interview by phone 10 months after the first one, she said the following:

Although I shed a few tears, I could drive home by myself. I did not give up having children. I got a sense of accomplishment because I did as much as I possibly could even though I had hoped to get pregnant without IVF.

She chose another practicing gynecologist to treat the endometriosis. However, she disclosed her slight hope of getting pregnant in saying,

I heard some episodes about infertility in which women could get pregnant when they stopped treating the infertility.

The doctor listened to her experiences and feelings. Then he suggested that she take low dose ovulation-inducing pills and a progesterone hormone injection to stimulate implantation instead of medicine to treat the endometriosis.

She also changed her part-time job to a clerk at a veterinarian; at the same time, she started a correspondence course to be certified as a nursery school teacher. This is an episode which shows the change in her attitude toward her childless condition. She spoke with pride as follows:

I have always worried if I would be asked about children. Indeed, it usually happens when I meet people for the first time. As I had feared, I was asked about children in front of all of the staff at the vet's. I responded that I could not have children, even though I had struggled with infertility treatment for several years. It was the first time that I had disclosed my experiences of infertility treatment in public. They might repeatedly ask the reason for my childlessness if I did not explain explicitly. They never asked again. Yesterday, I attended the Buddhist memorial service for my husband's late father. I have hated attending ceremonies because many relatives get together and some ask me about children. I usually responded to these insensitive questions, saying only “not yet” with a constrained smile, then I would get depressed later. But yesterday I answered only that I cannot have children yet. Further, I could hold my baby niece with pleasure. Actually, I envy my brother-in-law and his wife, but I did not get depressed at all.

After 7 months, I was notified in a brief letter of Ayako's pregnancy and premature delivery. I sent a card and then waited for a few months to call her. She was 29 years old when she gave birth. In 1995, I conducted the third interview with her on the phone. She described in detail what had happened since our last conversation.

Right after the second interview, she missed getting the injection to stimulate implantation because of her busy schedule but realized her B.B.T. was still in the high phase. When she talked about it with her husband, he told her that he did not want to get false hopes. So she bought a pregnancy test at a drug store and checked it alone the next day. It showed positive. Rather than being pleased by the result, she was upset. So upset that she later realized that the clothes she was hanging out to dry at the time were in disarray.

She made an appointment with her doctor and went to see him with her husband. The doctor was surprised to see the positive result of the pregnancy test which he conducted. However, he was very careful to confirm the pregnancy and considered the possibility of ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage because he could not see the fetus by ultrasound. After a few weeks, Ayako and husband went to see the doctor again. At last he said, “Congratulations” when he checked the fetal heartbeat. Ayako said that she was relieved when she watched the fetus's heartbeat on the monitor. But she began to worry about miscarriage.

Since I could not feel it was real, I felt just a little happiness. Then I assumed that I could not have a child anymore if I would have a miscarriage. The idea made me nervous.

Immediately after the doctor confirmed the pregnancy, Ayako and her husband told his mother but cautioned her not to tell anyone else for a while because the couple were worried about the possibility of a miscarriage.

Six weeks before the due date, Ayako started to bleed. So she was sent to a major hospital, where she received drugs to prevent premature labor. However, 5 days later, she bled again, so the doctor at that hospital recommended that labor be started by oxytocin injection. At 35 weeks' gestation, she vaginally delivered a 2.5 kg baby boy, who had to spend 1 day in an incubator. She worried a lot because the baby was at risk for various complications, including retinopathy, due to prematurity. The boy required very frequent breast feedings because he could suck milk from his mother's breast only little by little. Further, she worried about her son's delayed development. She was discharged after a week, but her baby remained in the hospital for nearly a month. Every day, she returned to the hospital to breastfeed.

After he was discharged, Ayako and her baby spent 1 month at her parent's house, as is often the case in Japan. Even with her mother's help and with supplemental formula, Ayako was exhausted by the many hours of breastfeeding. It caused Ayako so much neck pain that she saw an orthopedist. The doctor recommended that she be hospitalized for a few days, but she was only able to go to the hospital twice for several hours during the daytime for treatment and rest. Her husband tried to help her as much as he could, but she said, “Rearing a child is pretty hard on me and I am often irritated. I also sometimes wish that I could go out with only my husband.” Everyone around her felt that she should be a good mother because she had waited for so long. “I wanted a baby, so I shouldn't think that rearing a child is hard.” She added this comment about her experiences with infertility and infertility treatment:

While I didn't have a child, I worried that people looked down on me because of my infertility, but I later realized that I need not have belittled myself. I could not understand why I had such low self-esteem.

In 1999, 4 years after the last phone interview, we met again in person at her condominium. She had had another son about 1 year earlier. She started talking about the development of her first son, who was obviously smaller than others until the age of two. When her son went for a routine health checkup for infants at a public health center, he was required to have a detailed checkup because of his delayed development. This happened twice in 2 years. When he was 2 years old, I received a New Year's greeting card from her.

Before I had a child, I imagined a kid must look like an angel. I realized it is not real at all. But all I can do now is hang tough, right?

Looking back to 1997, she was astonished that her second pregnancy happened without infertility treatment. She had a vaginal birth with the help of a doctor and three nurse-midwives. The baby was a 3.0 kg boy. He sucked at the breast well and slept well. She felt that it has been much easier rearing the second baby.

However, the first son got jealous of the baby and became naughty. She confided that she sometimes spanked the children. She remembered she criticized mothers who abused their kids when she watched the TV news or magazines while she was seeking to have children. But now she seemed to understand how and why mothers sometimes do abuse their children. She pointed out that it was difficult to keep her cool when she spends too long a time in a closed space with only her children. Even though she sometimes minded the meddling of her mother-in-law, Ayako appreciated her help. Therefore, she was willing to live with her mother-in-law at her husband's extended family's house. She supposed that she could have a good relationship with her mother-in-law and it would have positive effect on her relationship with her children. She was 34 years old.

I received a change-of-address card from Ayako in 2002. She put in a brief note to me, “We decided to live with my husband's mother at her house, so he requested a transfer within the company to the city near his hometown. In addition, our first son entered elementary school.” She had just turned 37 years old.

4.1 What is Learned from Ayako's Life History

Here, I explain Ayako's life choices in the context of the Japanese social dimension. When she was in high school, the percentage of women attending high school was about 95% and for college, including junior college, attendance was about 33%. Footnote4 According to the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, the average age to marry was 25.8; by contrast, Ayako's age at marriage was 24 in 1989. Footnote5 About 80% of women in their first marriage have their first child in the first 2 years after marriage if they marry in their mid-20s. Footnote6 And among couples who continue their marriage from 5 years to 9 years, about 10% are childless and for those together for over 10 years, about 5% are. Footnote7 Especially, the ratio of childlessness when the woman is a housewife is lower. It can be said that Ayako's life course until marriage was average so that it must have been hard for her to accept her infertility. Indeed, she said, “It happened unexpectedly and I could not believe it at all, even after I was diagnosed with endometriosis.”

Ayako's life history seems to demonstrate how infertility treatment provides a solution not only for the problem of childlessness but also for the problem of how to improve relationships with other people. I think, however, her decision to stop IVF changed her view of herself before she had her children, and led to her becoming more assertive. She learned that she needed to make her own decisions regarding her infertility treatment. She was able to direct her own life course. For example, she changed her job and started taking a course to be a nursery school teacher because she said that even if she couldn't have a baby, she wanted to work with children. (However, she stopped taking the course after she had her sons.) She was also able to disclose her infertility to colleagues and to relatives. Additionally, whereas before she worried that people looked down on her because of her infertility, she later realized that she need not have belittled herself. She didn't understand why she had had such low self-esteem during her infertility treatment. Finally, she gained enough confidence in her ability to deal with her husband's extended family that she decided to live with her mother-in-law. As a housewife in Japan, she has both the responsibility for and the discretionary power over her household's economy.

Before we move to consider, I would like to show some more cases from my interviews to understand similarities and differences among interviewees.

4.2 Not for Providing a Family Heir but for Leaving a Small Mark on the World: Seiko's Case

Seiko was born in Tokyo in the late 1940s, which was the Japanese baby boom period. After she graduated from university, she obtained a good position, which she held until 2006, as a researcher at a private company's institution. She got married at 35 years of age after a 10-year de facto relationship. She is the elder in a family of two girls, but her parents have never mentioned atotsugi, or heir. She emphasized that she wanted a baby in order to prove her love for her husband and to give her life meaning. She also said that she wanted to do for her child what her parents did for her.

She started infertility treatment soon after her marriage because she had doubts about her fertility. She experienced a few side effects after taking hormonal injections and pills and became concerned with the long-term adverse effects of hormonal drugs. In the early 1990s, the doctor recommended that she undergo a laparoscopic examination. She felt very uneasy about the risks of the general anesthesia required for the procedure because one of her close friends came out against that type of examination after an incident with general anesthesia happened at the same hospital where her friend underwent gynecological surgery.

I went to see her at the hospital a day before her laparoscopic examination. I asked how she made her decision about the examination, and with a smile, she answered:

I would like to have anything possible done to have children, even if causing a risk to my life. Assuming the worst case, I implicitly conveyed my final words to people close to me before the exam.

After the examination, she was transferred to another university hospital with IVF specialists. However, most of them seemed reluctant to conduct IVF on her because she was in her mid-40s. There was only one doctor who was even willing to consider IVF on her. After the doctor honestly let her know that IVF is not a well-established technology, she agreed with him because she was also aware of the low success rate as well as its risks. However, her choice was different from what she considered reasonable.

I did not have any choices other than IVF. Although I was not much motivated to take it, I did not feel a strong resistance, either. If there is a technology available for use, I would like to try it regardless of its low success rate because I do not want to give up before exhausting all means. Being a professional in the laboratory, I believe that science and technology are developing with defects and failures. For example, while the development of science and technology causes environmental pollution, it is also able to bring solutions. Well, although I understand the development of technologies for infertility treatment is mainly for doctors and the medical association but not for patients, I strongly felt that I should try to undergo new technologies not only for myself but also for future patients. In other words, I do not mind being a “guinea pig” because I do not want other women to have the same experience as I had when I was suffering from infertility. These are all the reasons why I would rather prefer to venture into new technologies. However, I think that I could have decided not to take IVF if I had been told there was a zero percent success rate. As long as the rate is not zero, I believe there is a chance of success, however small it is.

After many failures of infertility treatment including IVF for 10 years, she registered her name on a waiting list for adoption although she was not optimistic about it because she was almost 50. After a while, I received a New Year's card from her. She wrote that she had adopted a daughter who was three and a half years old and diagnosed with a possible adjustment disorder.

In 1999, when I met her for the second interview, her daughter was in elementary school. Seiko told me excitedly that her daughter had brought her a new network in the community. She emphasized she could not have such a network without her child. She was worried about the diagnosis of her daughter as ADHD; however, she tried to think positively with her partner. Still, she stated as follows:

I think that the problem of infertility will last until the grave. My daughter will always be conscious about how she became my daughter, as well as the relationship between her and her parents and the reason why she was adopted, even if I don't know that exactly.

What Seiko said to me gave a lot of clues to consider regarding what infertility treatments imply. Before moving to my conclusion, I would like to describe three more stories of life after infertility treatment.

4.3 Wistful Giving Up: Shinobu's Case

Because of her family's economic situation, Shinobu had given up going to junior college even though she wanted to become a nursery teacher. Instead, she got a barber's license after high school. At age 24, she married a fellow barber. They run a barber shop. She reported that her relationship with her family of origin was not so happy and that ever since she was young, she wanted to have children as soon as possible to build a loving family. However, her husband was diagnosed as male infertile.

After many trials of infertility treatment such as AIH, they decided to try GIFT and IVF, which were the most advanced technologies in 1993. She was not fully confident about those technologies although she did not perceive them negatively, either.

I was disappointed by another failure. I feel an excruciating pain now but I feel more strongly regret. Although I did whatever I could do for infertility treatment, I failed. I know I have to accept this as reality. I think what I should do now is to take a rest for a while. I also understand that I should not be too serious about the result in order to avoid further exhaustion.

She wanted to try them together again at once. However, her husband insisted that she needed to rest for a year. He was very worried about her physical and psychological health because he knew her experience with a series of hormonal injections had been unbearable for her, and she was depressed after the failures. He became skeptical about the effects of these treatments.

In 1994, she prevailed on her husband to undergo ICSI, which is the most advanced technique for male infertility. It costs approximately ¥500,000 per treatment, which is more expensive than IVF, and the expenses would place a big burden on them economically. At last, her husband accepted her request to try ICSI again. She understood it would be the last chance for her. When the treatment failed again, she suffered physical pain and was frustrated by her keen sense of emptiness as explained in the beginning of this section.

After this, when she asked her husband to try ICSI one more time, he was strongly reluctant to accede to her request. However, she still held her wish to have children and form her ideal family. Her husband definitely disagrees with ICSI because her health is the most important thing to him, not because he is trying to save money. I also interpret that he feels guilty for his ignorance about her sufferings due to his infertility. She is proud of her husband because he is diligent and tender towards her. She has no intention of applying for ICSI as long as he does not agree because she knows that he also suffers from his own problems with male infertility.

In 1999, she reported to me again that she would not go to the hospital anymore but could not give up on having children. Although she wished she could have dropped the desire for children, she could not yet. She knows that she needs to have another aim in life, but she could not find one yet. When she underwent infertility treatment, she was very positive about everything. She established a patient support group in the hospital and organized several seminars about infertility. She believed that infertility treatment would enable her to have children; however, all the efforts she made were in vain.

She is currently surviving with depression, seeking to be released from her desire for having children, which she cannot give up completely. She consulted a counselor and a psychiatrist; however, they could not help her.

She had given up many things, but at the same time she has gained many things by her efforts. Shinobu's case reveals the fact that people tend to exploit technologies whenever they are available to fulfill their hopes. Even if one has a lot of negative information about the technologies which one may choose, it is difficult to resist the desire to try them, and that is why we have to be careful when we use the word, “choice” which sometimes implies self-determination.

4.4 Resisting Parents-in-law's Expectation of a Grandchild: Kumi's Case

Unlike Shinobu, Kumi decided by herself to stop her treatment. Both she and her husband were diagnosed with infertility, but she felt her mother-in-law was bitter against her because of their childlessness. She explained her problems with GIFT. She underwent GIFT twice in 1991, when it was recognized as a new technology introduced for assisted reproduction in Japan. After the second trial of GIFT, Kumi collapsed at the hospital because of anemia. While she was hospitalized, she was assured that all her efforts were futile attempts. Leaving the hospital, she decided not to continue infertility treatment.

When the doctor told me of the failure, I apologized to him that I could not get pregnant. I felt that I was responsible for the failure at that time. I don't know why. After I decided not to repeat the treatment for the sake of my husband and for my parents-in-law, I realized I was not really interested in rearing children.

When she told her decision to one of her friends who had a baby through IVF, the friend said, “You haven't tried IVF yet. You should do it if you want a child.” After this, she felt encouraged to have IVF, despite her previous decision not to continue infertility treatment. However, eventually, she decided not to undergo IVF because she was exhausted by the treatment, and she realized that rearing children was not something she wanted to devote herself to.

In 1999, she said that she dreamed of being an ordinary housewife with children. Because she is from a family which runs a Japanese hotel, everyone in the family is devoted to their guests, not their children. Caring for her elderly mother, she thought about what family is. She also said that she accepted the monotony of getting old with her husband.

4.5 Starting and Stopping IVF: Yumi's Case

Yumi had been a teacher at a preschool for 3 years. She left the school and soon got married. She said her goal is to have an ordinary life, which to her means to be a housewife with children. She felt alone in a new house in a new residential area. She and her husband saw a doctor, and infertility was diagnosed without clear cause. They started infertility treatment.

At the first interview in 1993, she emphasized that she and her husband were not willing to undergo IVF because they feared the “unnatural” medical technology. She decided to take hormonal drugs first, and later, underwent AIH repeatedly. She said that even AIH seemed unnatural, but she had no choice. The doctor recommended that she undergo GIFT; however, she decided not to do so because it would impose physical strain and is very expensive. After this, the doctor recommended IVF.

She was not sure whether IVF would be beneficial to them or not and asked her husband if he would agree to try IVF just once. Although her husband was dismissive of IVF, he accepted her proposal. Soon after she underwent IVF, she was told that IVF had failed. She was so shocked and exhausted that she decided to suspend the treatment for a while. She added that she would not try IVF anymore even after restarting infertility treatment. However, in 1999, I heard from Yumi that she could not stop trying IVF repeatedly. In 1999, replying to my request for another interview, she wrote:

In 1996, I underwent the sixth IVF treatment; however, it failed. In a deep depression, I courageously decided to discontinue infertility treatment. There is a handicraft shop where I often bought small things on my way home from the hospital. On the day that the doctor told me of the 6th failure, the store manager all of sudden asked me whether I was interested in working as a part-time clerk at the shop. I was surprised but really pleased by her offer. Since then, I have been working two days a week. I enjoy the job a lot.

It is difficult to recall many, miscellaneous things from when I was under infertility treatment. I cannot remember how my experiences of IVF were. I do not think IVF is anything special to do. I do not know why I underestimated myself during infertility treatment.

She has never restarted her treatment since 1996.

4.6 Keep Trying: Kiyoko's Case

Kiyoko was born in a metropolitan area in 1957 and graduated from a prestigious university after attending an affiliated junior-high and high school. She had liked her job at an advertising agency, but quit when she married. She then began working at a small insurance agency which her mother owns. Since she had not got pregnant for 3 years after her marriage, she went to a university hospital and was diagnosed with unexplained infertility. Right after she started infertility treatment, her father was hospitalized and then passed away; she had been caring for him. Kiyoko intended to pause her treatment but stopped going to the hospital after her father's death. Because she hesitated to restart infertility treatment, she tried many things for her health, such as seeing a chiropractor and reading many books about infertility, including feminist critiques of new reproductive technologies, and attending a course of feminist therapy. When she was 33 years old, she decided to restart her treatment at another university hospital which is famous for ART. When she participated in a prep class for infertility treatment in the hospital, she concluded she did not like the program. Therefore, she also went to a clinic which is available to prescribe kanpoyaku (Japanese traditional herbal medicine originated in China). In 1991, just before the first interview, she had gotten pregnant and delivered a boy.

At a second interview in 1994, she thought back over her experiences. She understood that being infertile is stigmatized when her friend congratulated her on her pregnancy. Her friend said, “I am very happy to hear about your pregnancy. I felt compassion that you had not gotten pregnant for so long.” She realized that she was pitied by her friends. It shocked her. Her baby suffered atopic dermatitis. She did everything she could for her baby, eating only good, organic foods cooked carefully, and went to a class for breastfeeding massage. She was exhausted by being a good mother.

In 1999, she described her analysis of her experiences to me. She told me that she has changed her views about her life after her experiences of infertility, rearing a child with atopic dermatitis, a miscarriage, and so on. She reflected that she had believed that “being normal” would be a natural and happy thing for her. She also explained, “I believed that your wish comes true if you keep trying. Therefore I always keep trying as much as possible. However, I learned from my experiences of infertility and rearing a child that we can't get everything we want.”

5 Conclusion

Through life histories of women who underwent infertility treatment, I explore the reasons why they endure grueling treatments and then why they cannot give up on having children even though they want to give up.

5.1 Difficulty Caused by Deviation from Cultural Norms

The desire of having children is interrelated to their life experiences. Shinobu sought to make a ‘happy’ family instead of her ‘unhappy’ birth family. Kumi sought to make an ‘ideal’ family which is different from her birth family that is always busy with the business. Both Shinobu and Kumi hope, not for a ‘special’ family but for an ‘ordinary’ one.

Being infertile is a deviation from cultural norms. Ayako, Yumi, and Kiyoko emphasized that they just want to have an ‘ordinary’ family. We, at least in Japan, believe that ordinariness is the best of states.

Some gynecologists I interviewed are very aware of the social dimensions of infertility. They realize that their patients suffer not only physically and emotionally from infertility but also socially and culturally. Although their expertise is limited to the physical, they emphasize that by solving the problem of infertility, the treatment, if successful, will have a positive outcome on the social situation as well (CitationTsuge 1999).

Reflecting such a situation, childless couples seem to feel that being a patient and relying on medicine and medical doctors are reasonable actions because there are a lot of success stories about infertility treatment in the media. Patients do not need to question why they seek children or undergo infertility treatment because many people are doing those things.

They stated that they did not want to give up having children without trying the medical technologies. Some of the interviewees said that they would not have undergone these technologies if they had known the risks and the low success rate. On the other hand, others said that they decided to try them despite the negative factors.

Becker and Nachtigall described the dilemma of involuntarily childless women and couples which was caused by medicalisation of infertility based on their interviews: (1) the disparity between initial expectations about ease and speed of treatment and its actual complexity; (2) the confrontation with medical definitions of abnormality; and (3) the cumulative effects of treatment, in which emotional exhaustion from infertility treatment vies with the continuing need to ‘fix’ the infertility and produce a pregnancy (CitationBecker and Nachtigall 1992: 465). Then they concluded that placing social problems within a biomedical framework does not provide a satisfactory solution for conditions that deviate from cultural norms, because those norms are replicated in biomedical ideologies about the nature and treatment of disease (ibid: 467).

I also analyzed the reasons women suffer infertility by the grounded theory approach as follows: (1) infertility causes gender identity crisis; (2) a woman who experiences infertility deviates from community and society's norms because of not being considered a “full-fledged” woman, or not a member of “allied mothers”; (3) alienation from their own bodies or the “natural body” Footnote8 model caused by infertility treatment; (4) low self-esteem as a wife and a daughter/daughter-in-law; and (5) the disappointment of not having one's expectations fulfilled despite having tried for many years (CitationTsuge 2000).

I would like to focus on the alienation from their own bodies caused by infertility treatment. Several interviewees in my study described how they were alienated from their bodies through infertility treatment. Like Kumi and Shinobu, each of the women said they felt guilty when the treatments failed, and it occurred to them that their bodies were not ‘normal’ or ‘natural.’ One interviewee, whose life history I have not shown here, who had a child after the 11th trial of AIH and a C-section, emphasized that she always feels marginalized even after having a child through infertility treatment, because she had an unusual experience of pregnancy and delivery, and she always feels different from and among “mothers who could have children easily and did not understand how infertile women and couples suffer.”

I think when a sense of alienation from their own bodies is caused by infertility treatment, women tend to seek the more advanced technologies to have their own babies, not to get their own bodies back. Therefore, I could say that infertility treatment dis-empowers women because of the associated medicalisation of the body as well as the social aspect. It must be an answer to what Ayako and Yumi each asked—why she underestimated herself during infertility treatment.

5.2 Ideology of Continuity of Family

Comparing the narratives of interviewees in my study in Japan with the narratives which Becker shows in her study in the USA (CitationBecker 2000), I realized that interviewees in my study emphasized conflict arising in relationships.

Interviewees in Becker's study usually express failures of medical treatments and their awful physical and psychological experiences which were caused by infertility treatment. It is true that they also described conflict with their partner and sometimes with their parents. On the other hand, interviewees in my study tend to narrate about the tension with their extended families and others rather than physical and psychological suffering from treatment and disappointment over the failure. They often mentioned what they were told about their childlessness by their parents, parents-in-law, siblings or siblings-in-law, relatives and/or friends. They complained that some asked them just the reason of childlessness, some admonished them about how having children is the happiest thing, not only for them but also for their parents. Although these people who gave unsought advice were not intending to harm childless couples, they have stigmatized people who suffer infertility. Thus, involuntarily childless couples are marginalized in society. Therefore, women who cannot have children tend to feel guilty that they cannot give their parents and parents-in-law that great ‘happiness’ even if infertility is caused by male factors or unknown. In other words, what makes infertility a serious problem is embedded in the relationships in family and community in Japan.

The relationship among extended family members and family norms in Japan has been dramatically changing in this half century (CitationAtoh 2004), but even now the extended family and relatives sometimes tend to provide intimate and supportive relationships at ceremonial occasions for marriage, funerals, and ancestral worship. According to government statistics, the ratio of people over 65 years old who live with their children was about 47% in 2002, compared to 69% in 1980. Although the rate has been decreasing, it is still high. For example, in a public poll, many married women answered that old-age support was a “natural duty of children” (35%) or “good custom” (16%) (CitationKuroda 2004).

In an extended family, the first son is expected to continue the family name; the family's real properties including a household grave; and the family business, if any. Although lately many families do not have any family businesses or have little family property to bequeath, especially in urban areas, the term atotsugi, meaning the person who is responsible for continuing their family line, is still alive in Japanese. However, because of the low birth rate in Japan, many couples have only a few children so that most children, either sons or daughters, are expected to be atotsugi.

Among the nine interviewees, five of the nine have husbands who are first sons, one of the nine wives is the only child of her parents, and two of the women with sisters but no brothers are expected to be atotsugi, according to traditional Japanese custom. Three of the nine have experienced being told that they should have children because they are atotsugi. However, the other three said they did not care even though they are conscious of atotsugi. An interviewee who is the only child of her parents said that her parents have never cared about atotsugi, and another interviewee, who is a first daughter among sisters, explained that neither she nor her sisters are expected to be atotsugi. These two interviewees live in a metropolitan area, have graduated from university, and have their own careers. The position of Ayako's husband, who is from a rural area and is conscious of his role as atotsugi, makes it more difficult for her to cope with her infertility, even though they also seek children for themselves.

All of the interviewees emphasized that although they wanted children for themselves and not for the sake of continuing the family line, they still feel guilty about not providing grandchildren for their parents to show off. In the Japanese cultural context, many expectant grandparents believe that grandchildren are extremely lovely and a pure pleasure to spoil.

Showing the story of a woman whose mother encouraged her not to give up having her biological child, Becker points out that the cultural ideology of generation continuity joins together with the cultural ideologies of biological parenthood and individualism, in which perseverance looms large (CitationBecker 2000: 188–193).

We can see the similarities and difference between what Becker calls “cultural ideology of generation continuity” and biological parenthood and individualism and the notion of atotsugi in Japan. It is interesting that the ideology of biological parenthood has become stronger in Japan just as the amendment of the family system in Civil Law in 1947 caused the ideology of atotsugi to diminish. That seems to explain why the number of adoptions has also decreased. Because the old family system absolutely needed atotsugi, the system of adoption was widely accepted as a cultural mechanism. Either the acceptance of adoption becoming narrower or the ideology of biological parenthood becoming stronger would stimulate medicalisation of infertility.

5.3 Akirameru—The First Step for Empowering

Concerning infertility, many women and couples use this word, akirameru after they realize they cannot have children in spite of infertility treatments. It is usually translated as “give up.” Becker pointed out the difference between “giving up” and “acceptance” of the failure of infertility treatment in Judeo-Christian culture. “Accepting a situation opens up the possibility of working around it and thus transforming it. The idea of accepting what cannot be changed enables people to focus their energies elsewhere” (CitationBecker 1997: 177). I could translate akirameru not to give up but acceptance. However, Becker described acceptance of what cannot be changed as part of the US value of perseverance. I think that akirameru is different from perseverance. Therefore, I use here “give up” when I need to express akirameru in English.

Here, I discuss the reason why interviewees express their feeling as akirame-tai noni akirame-rarenai, which means they cannot give up even though they want to give up. The verb akirameru is frequently used in various contexts. Japanese usually use two different kanji or Chinese character presenting akirameru. One meaning of akirameru (諦める) is similar to “give up”, “forsake”, “abandon”, “reconcile”, “surrender”, and so on. Another meaning of akirameru (明らめる) is similar to “come to light”, “come out”, “clear up”, etc. I would like to explain the meaning of akirameru represented by the second kanji. If a person can akirameru, she or he can move on without repenting what they did.

When Ayako decided to stop IVF, she expressed her slight hope of getting pregnant saying, “I heard some episodes about infertility in which they could get pregnant when they stopped treating the infertility.” It shows she had not given up having children yet. On the contrary, Ayako disclosed her infertility to her mother-in-law, who ardently desires a grandchild, and to relatives and coworkers. Obviously, Ayako knew she would be looked at with a great deal of curiosity if she disclosed her infertility. That is a reason why she had concealed the problem.

I interpret that changing her attitude to others represents her empowering. It came about that she became tough enough to deal with the desire of her mother-in-law and endure meddlers. As Ayako said, “I got a sense of accomplishment because I did as much as I possibly could even though I hoped to get pregnant without IVF.” This sense of akirameru implies a process of empowerment, for “getting over” or “accepting” difficulties.

Ayako realized that the expectation of “atotsugi” in rural Japan affected her status and her relationship with her mother-in-law. Even though she did not overtly resist her role as a daughter-in-law, she became able to manage the family situation after understanding that she did not need to belittle herself because of her infertility.

Yumi underwent IVF six times and stopped it. When she decided to withdraw from infertility treatment, she got a part-time job. She described how she has good relationship with her coworkers. While she underwent infertility treatment, she complained about her isolation within the community. She said that she could not understand why she underestimated herself while having the treatment.

Kumi also kept secret from undergoing infertility treatment to her parents-in-law even though they asked about their plans for having children. After failure of her second trial of GIFT, her mother-in-law unknowingly told Kumi to undergo infertility treatment. She argued back to her mother-in-law. Kumi said that the incident made her stop infertility treatment.

Another noticeable point is a sort of morality which is embodied in the interviewees who are in the same generation. Kiyoko, a well-educated career woman explained in an interview, “I believed that your wish comes true if you keep trying.” Her generation also believes that technologies have been developing progressively in modern history in Japan and have brought many benefits, which becomes an implicit pressure for women to try them before they decide to seek alternatives. Therefore, it is very hard for the interviewees to give up trying infertility treatment repeatedly. Thinking about Shinobu who is suffering her depression after infertility treatment, we remember that she often said akirame-tai noni akirame-rarenai. Her childlessness is caused by male infertility. In addition, she could not keep trying ICSI because her husband asked her to withdraw the treatment for her health.

What I want to point out is people can akirameru when they are empowered and deal with problems caused by infertility. I can say the attitude—akirameru—is a first step of empowering for a woman who suffers from infertility and prolonged infertility treatment. To paraphrase, a woman who suffers from infertility and infertility treatment is empowered when she becomes unafraid to deviate from cultural norms.

We who live today in this so-called global high-tech age need to have quite extraordinary powers of endurance in order to deal with reproductive issues and technologies. Therefore, it is very important for us to realize what causes our suffering. A problem difficult to resolve is created if people seek the solution in medical technologies without considering issues, and without empowerment to deal with problems.

I would like to acknowledge all interviewees for participating in my research for a long time. I also gratefully acknowledge comments from two anonymous referees. The launch of this research was supported by Toyota Foundation in 1992–1993.

Notes

1 Source: The Journal of Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology 59(9): 1717–1739, 2007.

2 There are two ways to spell either ‘medicalisation’ or ‘medicalization’.

3 The government has subsidized patients' use of assisted reproductive technologies since 2003.

4 Source: Minister of Education, Science, Culture. The rate of women attending high school was about 97% and college, including junior college, attendance was about 49% in 2000.

5 Source: The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. The average age of women at first marriage is increasing. It was 27.6 years old in 2003 and 28.2 years old in 2006.

6 The number is an estimate by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.

7 These numbers are estimates by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research.

8 See Lock (Citation1997).

References

- Arditti R. Klein R. D. & Minden S. (Eds.) (1984) Test-tube women: what future for motherhood? London: Pandora Press.

- Atoh M. (2004). Changing family norms and lowest-low fertility. In Changing family norms among Japanese women in an era of lowest-low fertility: summary of the first National Survey on Population, Families and Generations in Japan. The Population Problems Research Council (ed.), Tokyo: The Mainichi Newspapers.

- Becker G. (1997). Disrupted lives: how people create meaning in a chaotic world. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Becker G. (2000). The elusive embryo: how women and men approach new reproductive technologies. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Becker G. , & Nachtigall R. D. (1992). Eager for medicalisation: the social production of infertility as a disease. Sociology of Health & Illness, 14(4), 456–471.

- Corea G. (1985). The mother machine: reproductive technologies from artificial insemination to artificial wombs. New York: Harper & Row.

- Clarke A. (2003). Biomedicalization: technoscientific transformations of health, illness, and U.S. biomedicine. American Sociological Review, 68(2), 161–194.

- Finrrage-no-kai (2000). Shin report funin: funin chiryo no jittai to seishokugijutu nituiteno ishiki chousa houkoku (New report on infertility: results of questionnaire survey related to the experiences and attitudes to infertility treatment by 857 members at a self-support group). Tokyo.

- Illich I. (1975). Limits to medicine: medical nemesis, the expropriation of health. London: Marion Boyars.

- Inhorn M. (1996). Infertility and patriarchy: the cultural politics of gender and family in Egypt. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press.

- Klein R. (Ed.) (1989) Infertility: women speak out about their experiences of reproductive medicine. London: Pandora.

- Kuroda T. (2004). Support system for old parents. In Changing family norms among Japanese women in an era of lowest-low fertility: summary of the first National Survey on Population, Families and Generations in Japan, edited by The Population Problems Research Council , Tokyo: The Mainichi Newspapers.

- Lock M. (1997). Decentering the natural body: making difference matter. Configurations: The Journal of Literature and Science, 5(2), 267–292.

- Thompson C. (2005). Making parents: the ontological choreography of reproductive technologies. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

- Tsuge A. (1999). Bunka-to-shiteno seishokugijutu: funin-chiryo ni tazusawaru ishi no katari (Reproductive technology as culture: narratives of Japanese gynecologists regarding infertility treatment). Kyoto: Shorai-sha.

- Tsuge A. (2000). Seishoku gijutsu to josei no shintai no aida (Rethinking new reproductive technology and woman’s ‘natural body.’ Shisou (Thought), no. 908, 181–198. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

- Warnock M. (1985). A question of life: the Warnock Report on Human Fertilization and Embryology. London: Blackwell.

- Zola I. K. (1972). Medicine as an institution of social control. The Sociological Review, 20, 487–504.