Abstract

The important question whether ‘mild’ hypertension should or should not be treated by drugs is difficult to answer, because the only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating this question were conducted when the definition of ‘mild’ hypertension was based on diastolic blood pressure only, whereas the present definition of grade 1 hypertension includes both systolic and diastolic values (SBP/DBP), and the concept of ‘mild’ hypertension also includes that of low-moderate cardiovascular risk (< 5% cardiovascular death rate in 5 years). Due to the lack of evidence from specific RCTs, guidelines recommend drug treatment of mild hypertension only on the basis of expert opinion. However, recent meta-analyses have provided some support to drug treatment intervention in low-moderate risk grade 1 hypertensives and have shown that, when treatment is deferred until organ damage or cardiovascular disease occur, absolute residual risk (events occurring despite treatment) markedly increases. Although evidence favoring therapeutic intervention in mild hypertension is nowadays stronger than expert opinion, meta-analyses are not substitutes for specific RCTs, and the wide BP spans defining grade 1 hypertension as well as the span defining low-moderate risk leave a wide space for individualized or personalized decisions.

The frequently posed question whether ‘mild hypertension’ should or should not be treated by blood pressure (BP)-lowering drugs is difficult to be answered, because the term ‘mild’ hypertension is an equivocal one. The term was widely used in the past, but in a sense different from that used now. As illustrated in , between 1977 and 1993 at least six randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were designed to investigate the benefits or harms of BP lowering in mild hypertension: the United States Public Health System trial on mild hypertension Citation[1], the Veteran Administration – National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Citation[2] trial, the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program (HDFP) stratum 1 Citation[3], the Australian Therapeutic Trial in Mild Hypertension Citation[4], the Oslo trial on mild hypertensives Citation[5], the Medical Research Council (MRC) Working Party on mild hypertension Citation[6] and the Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study Citation[7], but all used criteria based on different ranges of diastolic BP (DBP), ignoring systolic BP (SBP) or allowing inclusion of quite high SBP values.

Table 1. Old trials on ‘mild’ hypertension.

However, during the 1990s with the publication of the results of the first RCTs on isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly, investigational and clinical interest began to shift from DBP to SBP, or, better to say, both SBP and DBP values were considered in the classification of hypertension. illustrates the classification used by the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) – European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines on the Management of Arterial Hypertension Citation[8], which is very similar to the one used by the Joint National Committee 7th report in the US Citation[9], with the difference that, in the latter, ‘grades’ are called ‘stages’ and grades 2 and 3 are summarized in a single stage 2 group.

Table 2. Definitions and classification of hypertension by office blood pressure levels (mmHg) in the ESH-ESC hypertension guidelines.

It was a critical review published in 2009 Citation[10] that first called attention to the fact that the evidence obtained in the 1977 – 1993 RCTs on mild hypertension could not safely be applied to what is now called grade (or stage) 1 hypertension because in the old RCTs on mild hypertension the range of DBP was beyond the current limit of grade 1 (99 mmHg) and a considerable number of patients had SBP beyond 159 mmHg and in four of the six RCTs SBP was entirely ignored (). The above-mentioned review also pointed out that the term ‘mild’ was somewhat equivocal since it was used to indicate a ‘mild’ BP elevation, but it also conveyed the wrong impression that the clinical condition of the patients was mild, while the overall risk of the patients depends not only on BP levels but also on concomitant risk factors and diseases: in fact, the ‘mild’ hypertensive patients of the HDFP trial had a 5-year cardiovascular mortality incidence about three times higher than the ‘mild’ hypertensives of the other trials, and in the range of what is now defined ‘high’ cardiovascular risk ().

Thus, the dilemma of treating or not treating mild hypertension can be better phrased now as that of treating or not treating grade (stage) 1 hypertension at low-moderate cardiovascular risk. As there has been no RCT specifically addressing this question and the results of the old ‘mild hypertension’ RCTs cannot be safely used to answer the new question, it is no surprise that recommendations about drug treatment in low-moderate risk grade 1 hypertension widely vary between available guidelines. The 2011 National Institute for Clinical Excellence UK guidelines Citation[11] recommend to limit drug treatment to those grade 1 hypertensive patients whose overall cardiovascular risk is high; the members of the Eighth Joint National Committee report (JNC-8) Citation[12] present as an evidence-based recommendation that of treating with BP-lowering drugs those individuals with DBP 90 – 99 mmHg (on the basis of the old ‘mild hypertension’ RCTs, but neglecting the fact that in these trials a considerable number of the patients had DBP and SBP values higher than grade 1 range) and recommends drug treatment of individuals with SBP 140 – 159 mmHg on the basis of expert opinion only; the 2013 ESH-ESC guidelines Citation[8] as well as those of the American and International Societies of Hypertension Citation[13] recommend drug treatment of low-moderate risk grade 1 hypertensive patients only after a prolonged attempt to lowering BP by lifestyle measures, but acknowledge this is not strongly based on trial evidence.

In lack of direct evidence from specific RCTs, some help in deciding about the dilemma of treating or not treating grade 1 hypertensive individuals and, in particular, those with low-moderate cardiovascular risk may come from meta-analyses. A meta-analysis by Czernichow et al. Citation[14] including a large number of trials in individuals at different baseline SBP and DBP levels showed significant risk reductions at all BP levels, including those within grade 1 ranges, but ‘initial’ BP levels were from individuals the majority of whom were already receiving antihypertensive treatment at the time of randomization, and therefore were different from the individuals for whom decisions on the initiation of drug treatment are taken. When an attempt was made to limit the meta-analysis to previously untreated patients, statistical power was too low to obtain significant results. Also, Law et al. Citation[15] and Thompson et al. Citation[16] have provided meta-analyses of the effects of antihypertensive drugs in individuals at different BP levels, but in these meta-analyses not only most patients were already under antihypertensive treatment at the time of randomization, but also many of those at the lowest BP values were patients with myocardial infarction or heart failure, and therefore these meta-analyses do not provide data applicable to grade 1 hypertensive patients. Furthermore, in both Czernichow et al. Citation[14] and Law et al. Citation[15] meta-analyses, risk reductions were separately calculated for SBP and DBP, whereas clinical definition of hypertension grade should be made considering both SBP and DBP.

Three recent meta-analyses have tried to overcome the limitations of these previous attempts by using two distinct approaches. The first approach is that of identifying within available RCTs of active BP lowering versus placebo (or of more versus less active treatment) those individuals matching the BP values defining grade 1 hypertension, and limiting the analyses to these precisely defined individuals. The potential advantage of this approach is that of focusing on correctly defined grade 1 individuals, provided that only RCTs with no baseline antihypertensive therapy are considered. The limitations are the post-hoc selection of individuals from a trial population that did not include that selection criterion, and, particularly, the small number of RCTs with individual patient information available to every meta-analysis collaboration, which makes the selection limited and potentially biased, and reduces the statistical power of the meta-analysis. A 2012 Cochrane meta-analysis focused on individuals in the old ‘mild’ hypertension trials who could be correctly defined grade 1 hypertensive Citation[17]. The Cochrane collaboration authors were unable to detect significant risk reductions by BP lowering in their grade 1 population, although stroke reduction came close to statistical significance. The Cochrane collaboration results are the basis for the frequent statement that no evidence is available favoring BP-lowering drug treatment in grade 1 hypertensive patients. However, the Cochrane collaboration meta-analysis had very low statistical power, including only 30 strokes (all from the MRC mild hypertension trial), 122 coronary events and 165 major cardiovascular events. Recently, the Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration (BPLTTC) has been able to increase the statistical power of the meta-analysis by adding data from individuals with baseline BP values within grade 1 range in other nine RCTs and has reported statistically significant reductions in the risks of stroke, cardiovascular and all-cause deaths, concluding that BP-lowering therapy is likely to prevent stroke and death in patients with uncomplicated grade 1 hypertension Citation[18]. The authors correctly acknowledge two limitations of their meta-analysis: i) about one half of the individuals they added to the Cochrane meta-analysis were receiving background antihypertensive treatment at baseline and their untreated BPs may have been above grade 1 hypertension; ii) the majority of the patients added to the Cochrane meta-analysis were from RCTs on patients with diabetes, and their overall cardiovascular risk was not trivial (cardiovascular death 6.2% over 10 years, beyond the upper < 5% cutoff for low-moderate risk).

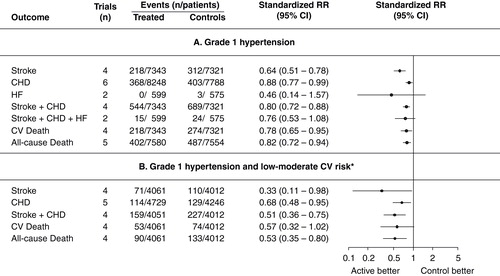

Thomopoulos et al. Citation[19] have followed another approach, that of using RCT data in their entirety or in predefined subgroups and stratifying them as grade 1, grade 2 and grade 3 RCTs according to the average SBP and DBP values at baseline in each trial. The advantage of this approach is the possibility to use data from all available RCTs in which no (or only minor) background treatment was present at baseline, thus avoiding post-hoc selection of individual participants and trial selection bias, and markedly increasing the statistical power of the meta-analysis. A limitation is that of probably including a number of patients with BP out of the range predetermined for stratifying baseline BPs. However, the number of patients out of the grade 1 range is likely to be small when the average BPs are near the middle value of the range. summarizes the results of this recent set of meta-analysis Citation[19]. Six trials in 16,036 individuals were classified as grade 1, and their meta-analysis showed significant reductions in the risk of stroke, coronary events, the composite of stroke and coronary events, cardiovascular and all-cause deaths (). As some of these trials included patients at high cardiovascular risk, another meta-analysis was done only including RCTs or RCT subgroups with mean baseline SBP/DBP values in grade 1 range and a low to moderate cardiovascular risk (< 5% cardiovascular death in 10 years in the control groups). Also in the 8975 patients of this meta-analysis, BP-lowering treatment significantly decreased the risk of stroke, coronary events, the composite of stroke and coronary events and all-cause death. Absolute risk reduction was large, amounting to 21 strokes, 34 major cardiovascular events and 19 deaths prevented every 1000 patients treated for 5 years (number needed to treat for 5 years to prevent a stroke 47, a major cardiovascular event 34, a death 19) (). In all trials considered above, hypertension was diagnosed by clinic (office) BP measurement without the help of 24-h ambulatory BP monitoring. Hence, though 24-h ambulatory monitoring is a more precise way of measuring BP, its added value in deciding initiation of antihypertension treatment has never been investigated in RCTs.

Figure 1. Effects of blood pressure lowering in trials of grade 1 hypertension. Grade 1 trials defined as those with average baseline SBP/DBP in the range 140-159/90-99 mmHg. (A) All grade 1 trials independent of total cardiovascular risk. (B) Only grade 1 trials or trial subgroups at low-moderate risk.

Expert opinion

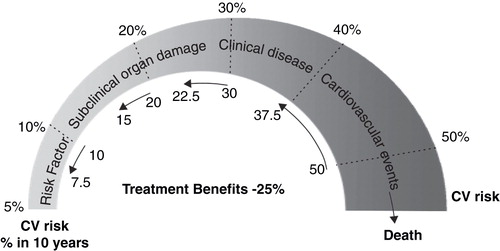

A definite answer to the impelling question whether patients with grade 1 hypertension and low-moderate risk (who can correctly be defined mild, as mild is the BP elevation and mild the overall risk) should or should not be treated cannot be provided yet in the lack of a trial specifically directed to investigate the question. Although such a trial is in principle desirable, it is quite unlikely that it will be conducted in the near future, because the relative low risk of the patients involved and the relatively smallness of the risk represented by a small BP elevation would require many thousands of individuals to be involved and many years of follow-up. In lack of a definite evidence, other data should be considered and the two recent meta-analyses by the BPLTTC Citation[18] and by Thomopoulos Citation[19] represent a support in favor of intervention definitely stronger than the expert opinions upon which similar recommendations by the European Citation[8] and the JNC-8 Citation[12] guidelines were based. It is true that in both the Cochrane collaboration and the BPLTTC meta-analyses on mild hypertension Citation[17,18] active treatment was associated with a higher level of withdrawals from treatment than no treatment, but in trials the rigid treatment protocol (the only alternative to the protocol drug is withdrawal) is bound to cause a higher rate of treatment withdrawal than in everyday medical practice, in which the most effective and better tolerated antihypertensive agent can be identified by trial and error. As remarked in the ESH/ESC hypertension guidelines, the good tolerability of the BP-lowering drugs now available and the wide range of choices among drug classes guarantee the risks of treatment are minimal. There is a further argument in favor of an early therapeutic intervention in hypertensive individuals. An additional set of meta-analysis by Thomopoulos et al. Citation[20] has shown that, although BP-lowering treatment induces greater absolute risk reductions the higher the cardiovascular risk level, this cannot be taken as an indication for restricting antihypertensive treatment to high risk patients only, because higher risk levels are associated with higher absolute residual risk, that is higher rates of events occurring despite active antihypertensive treatment Citation[21]. illustrates the natural history of cardiovascular disease as a continuum of increasing risk Citation[22]: at any stage of the continuum BP lowering is beneficial, with a relative (percent) risk reduction that meta-analyses have shown to be similar through the cardiovascular disease continuum Citation[20]. Thus, absolute residual risk can be maintained low only if intervention is initiated before irreversible or scarcely reversible organ damage or cardiovascular disease develops. Therefore, delaying treatment to the appearance of signs of organ damage is, at least, disputable. If recent meta-analyses support prudent BP-lowering drug intervention in grade 1 hypertension, the span of BP values included in this grade of hypertension (SBP from 140 to 159 mmHg, and DBP from 90 to 99 mmHg) as well as the span of low to moderate cardiovascular risk (from 0 to 5% cardiovascular mortality in 10 years) leave a range of flexibility to the physician’s decisions, based on sex and age, concomitant risk factors, organ damage assessment, individual adherence to lifestyle recommendations and tolerability to drugs. Grade 1 hypertension with low-moderate cardiovascular risk remains an area in which individualized or ‘personalized’ medicine has an obvious space.

Declaration of interest

A Zanchetti has received lecture honoraria from Menarini Int, Recordati Spa, CVRx. The author has no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Notes

Bibliography

- Smith WM. Treatment of mild hypertension: results of a ten-year intervention trial. Circ Res 1977;40:I98-105

- Perry HMJr, Goldman AI, Lavin MA, et al. Evaluation of drug treatment in mild hypertension: VA-NHLBI feasibility trial. Plan and preliminary results of a two-year feasibility trial for a multicenter intervention study to evaluate the benefits versus the disadvantages of treating mild hypertension. Prepared for the Veterans Administration-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute study group for evaluating treatment in mild hypertension. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1978;304:267-92

- Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. JAMA 1979;242:2562-71

- Management Committee. The Australian therapeutic trial in mild hypertension. Lancet 1980;315:1261-7

- Helgeland A. Treatment of mild hypertension: a five year controlled drug trial. The Oslo study. Am J Med 1980;69:725-32

- Medical Research Council Working Party. MRC trial on treatment of mild hypertension: principal results. Br Med J 1985;291:97-104

- Neaton JD, Grimm RHJr, Prineas RJ, et al. Treatment of mild hypertension study. Final results. Treatment of mild hypertension study research group. JAMA 1993;270:713-24

- Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. The task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens 2013;31:1281-357

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003;42:1206-52

- Zanchetti A, Grassi G, Mancia G. When should antihypertensive drug treatment be initiated and to what levels should systolic blood pressure be lowered? A critical re-appraisal. J Hypertens 2009;27:923-34

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Hypertension (CG127): clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG127

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults. Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2014;311:507-20

- Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White B, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: A statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens 2014;32:3-15

- Czernichow S, Zanchetti A, Turnbull F, et al. The effects of blood pressure reduction and of different blood pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events according to baseline blood pressure: meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Hypertens 2011;29:4-16

- Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. Br Med J 2009;338:b1665

- Thompson AM, Hu T, Eshelbrenner CL, et al. Antihypertensive treatment and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease events among persons without hypertension: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2011;305:913-22

- Diao D, Wright JM, Cundiff DK, et al. Pharmacotherapy for mild hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;8:CD006742

- Sundström J, Arima H, Jackson R, et al. Effects of blood pressure reduction in mild hypertension. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:184-91

- Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension. 2. Effects at different baseline and achieved blood pressure levels. Overview and meta-analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens 2014;32:2296-304

- Thomopoulos C, Parati G, Zanchetti A. Effects of blood pressure lowering on outcome incidence in hypertension. 3. Effects in patients at different levels of cardiovascular risk. Overview and meta-analyses of randomized trials. J Hypertens 2014;32:2305-14

- Zanchetti A. Bottom blood pressure or bottom cardiovascular risk? How far can cardiovascular risk be reduced? J Hypertens 2009;27:1509-20

- Zanchetti A. Hypertension: Cardiac hypertrophy as a target of antihypertensive therapy. Nat Rev Cardiol 2010;7:66-7