Abstract

Response to: Kumar R, Bhatia A. Common variable immunodeficiency in adults: current diagnostic protocol and laboratory measures. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 10(2), 000–000 (2014).

We read with interest the article published by Drs Kumar and Bhatia on common variable immune deficiency (CVID) Citation[1]. Our recent paper Citation[2] on proposed new criteria for CVID was cited in the review by Kumar and Bhatia. A table (Box 2 in the article Citation[1]) similar to our diagnostic criteria appears to have been attributed to us, along with diagnostic Categories A–D.

CVID is probably a heterogeneous group of polygenic disorders culminating in late-onset antibody failure. It is unlikely that a single diagnostic genetic test will become available in the foreseeable future. This is a difficult area as we have many patients with profound laboratory abnormalities who are relatively well Citation[3]. Other patients are very ill with extensive suppurative lung disease but have minimal laboratory abnormalities. As the cause(s) of this/these complex disorder(s) is/are not known, our criteria were designed to ensure that patients with immune system failure (ISF) would be identified and treated with immunoglobulin. The main difference between our proposed criteria and the European Society of Immune Deficiency and Pan-American Group for Immune Deficiency is the emphasis on clinical symptoms of ISF. Given the difficulties assessing vaccine responses Citation[2], this aspect of the diagnosis has been de-emphasized in our criteria.

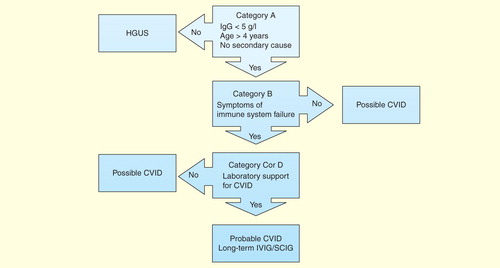

Our criteria comprise four parts . Patients must meet the major criteria in Category A. Adult patients must have an IgG < 5 g/l (not 4.5 g/l), which is the cutoff used in the French DEFI study Citation[4]. This is well below the two standard deviations for IgG as stated in the Pan-American Group for Immune Deficiency/European Society of Immune Deficiency criteria Citation[5]. Patients must be over 4 years of age Citation[6] and must not have a secondary cause for their hypogammaglobulinemia Citation[7].

Table 1. Proposed diagnostic criteria for common variable immune deficiency.

If patients satisfy Category A criteria, then they must have clinical evidence of ISF, usually susceptibility to infections or autoimmunity (Category B criteria). They must then meet Category C or D criteria. Category C criteria consist of a series of laboratory findings, which are not specific on their own but in combination will support the diagnosis of CVID. Category D consists of characteristic histological findings in CVID, which are consistent with the diagnosis. Patients meeting Categories A, B and C or D have probable CVID and will qualify for long-term immunoglobulin treatment . Those patients meeting only Category A have possible CVID and some with profound hypogammaglobulinemia will qualify for immunoglobulin treatment Citation[2]. Those with mild reductions in IgG have been termed hypogammaglobulinemia of uncertain significance. These patients will need long-term follow-up as some will evolve into CVID. The diagnostic and treatment algorithm is shown in .

Figure 1. Diagnostic and treatment algorithm for common variable immune deficiency. Patients must meet all major criteria in Category A for consideration of CVID. Category B confirms the presence of symptoms indicating immune system failure. To have probable CVID, patients must also have supportive laboratory evidence of immune system dysfunction (Category C) or characteristic histological lesions of CVID (Category D). Patients with mild hypogammaglobulinemia (IgG >5 g/l) are termed hypogammaglobulinemia of uncertain significance (HGUS). Patients meeting Category A criteria but not other criteria are deemed to have possible CVID. Most patients with probable CVID are likely to require IVIG/SCIG. Some patients with possible CVID will require IVIG/SCIG, but most patients with hypogammaglobulinemia of uncertain significance are unlikely to need IVIG/SCIG replacement.

We are in the process of validating these criteria with the New Zealand hypogammaglobulinemia/CVID cohort. These criteria will need international consensus and endorsement by immunology societies. Having uniform criteria will assist with treating individual patients. It will also allow comparison of international cohorts of patients, who may have different clinical features and complications. Having a characteristic histological lesion may obviate the need to stop immunoglobulin treatment to assess vaccine responses. This process can take several months and patients may be at risk of infections during this time. These criteria will also help identify common and unusual causes of secondary hypogammaglobulinemia Citation[8].

While we welcome the publication of our criteria in peer-reviewed journals, our main concern is that our table of diagnostic criteria has been substantially modified by Kumar and Bhatia, which will significantly alter its diagnostic utility. Our original publication had eight criteria in Category C and patients were required to meet three criteria to qualify. In the Kumar publication Citation[1], these were shortened to five (Box 2), which will significantly reduce the probability of patients with CVID meeting three of these criteria. Furthermore, we have not suggested assessing only responses to protein (T cell-dependent) vaccines as stated in the Kumar publication. There is also no mention of mutations in genes, such as TACI or BAFF receptor, which may predispose to CVID in the modified table.

Our concern is that if patients do not meet the criteria in the Kumar publication, there is a risk that their immunoglobulin treatment may not be funded in some parts of the world. We request that any authors citing our work in the future, reproduce our criteria accurately to reduce the risk of confusion. This would be expected when citing the Jones criteria for acute rheumatic fever or the American College of Rheumatology criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

R Ameratunga has received an unrestricted educational grant from Octapharma. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Notes

References

- Kumar Y, Bhatia A. Common variable immunodeficiency in adults: current diagnostic protocol and laboratory measures. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2013;9(10):959-77

- Ameratunga R, Woon ST, Gillis D, et al. New diagnostic criteria for common variable immune deficiency (CVID), which may assist with decisions to treat with intravenous or subcutaneous immunoglobulin. Clin Exp Immunol 2013;174(2):203-11

- Koopmans W, Woon ST, Brooks AE, et al. Clinical variability of family members with the C104R mutation in transmembrane activator and calcium modulator and cyclophilin ligand interactor (TACI). J Clin Immunol 2013;33(1):68-73

- Oksenhendler E, Gerard L, Fieschi C, et al. Infections in 252 patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46(10):1547-54

- Conley ME, Notarangelo LD, Etzioni A. Diagnostic criteria for primary immunodeficiencies. Representing PAGID (Pan-American Group for Immunodeficiency) and ESID (European Society for Immunodeficiencies). Clin Immunol 1999;93(3):190-7

- Chapel H, Cunningham-Rundles C. Update in understanding common variable immunodeficiency disorders (CVIDs) and the management of patients with these conditions. Br J Haematol 2009;145(6):709-27

- Agarwal S, Cunningham-Rundles C. Assessment and clinical interpretation of reduced IgG values. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2007;99(3):281-3

- Ameratunga R, Casey P, Parry S, Kendi C. Hypogammaglobulinemia factitia. Munchausen syndrome presenting as common variable immune deficiency. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2013;9:36

- Knight AK, Cunningham-Rundles C. Inflammatory and autoimmune complications of common variable immune deficiency. Autoimmun Rev 2006;5(2):156-9

- Cunningham-Rundles C, Bodian C. Common variable immunodeficiency: clinical and immunological features of 248 patients. Clin Immunol 1999;92(1):34-48

- Chapel H, Lucas M, Lee M, et al. Common variable immunodeficiency disorders: division into distinct clinical phenotypes. Blood 2008;112(2):277-86

- Wehr C, Kivioja T, Schmitt C, et al. The EUROclass trial: defining subgroups in common variable immunodeficiency. Blood 2008;111(1):77-85

- Abrahamian F, Agrawal S, Gupta S. Immunological and clinical profile of adult patients with selective immunoglobulin subclass deficiency: response to intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Clin Exp Immunol 2010;159(3):344-50

- Olinder-Nielsen AM, Granert C, Forsberg P, et al. Immunoglobulin prophylaxis in 350 adults with IgG subclass deficiency and recurrent respiratory tract infections: a long-term follow-up. Scand J Infect Dis 2007;39(1):44-50

- Musher DM, Manof SB, Liss C, et al. Safety and antibody response, including antibody persistence for 5 years, after primary vaccination or revaccination with pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in middle-aged and older adults. J Infect Dis 2010;201(4):516-24

- Tiller TL Jr, Buckley RH. Transient hypogammaglobulinemia of infancy: review of the literature, clinical and immunologic features of 11 new cases, and long-term follow-up. J Pediatr 1978;92(3):347-53

- Pan-Hammarstrom Q, Salzer U, Du L, et al. Reexamining the role of TACI coding variants in common variable immunodeficiency and selective IgA deficiency. Nat Genet 2007;39(4):429-30

- Salzer U, Bacchelli C, Buckridge S, et al. Relevance of biallelic versus monoallelic TNFRSF13B mutations in distinguishing disease-causing from risk-increasing TNFRSF13B variants in antibody deficiency syndromes. Blood 2009;113(9):1967-76

- Popa V. Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia of common variable immunodeficiency. Ann Allergy 1988;60(3):203-6

- Ameratunga R, Becroft DM, Hunter W. The simultaneous presentation of sarcoidosis and common variable immune deficiency. Pathology 2000;32(4):280-2

- Fasano MB, Sullivan KE, Sarpong SB, et al. Sarcoidosis and common variable immunodeficiency. Report of 8 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1996;75(5):251-61

- Fuss IJ, Friend J, Yang Z, et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia in common variable immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol 2013;33(4):748-58

- Malamut G, Ziol M, Suarez F, et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia: the main liver disease in patients with primary hypogammaglobulinemia and hepatic abnormalities. J Hepatol 2008;48(1):74-82

- Luzi G, Zullo A, Iebba F, et al. Duodenal pathology and clinical-immunological implications in common variable immunodeficiency patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98(1):118-21

- Malamut G, Verkarre V, Suarez F, et al. The enteropathy associated with common variable immunodeficiency: the delineated frontiers with celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105(10):2262-75

- Agarwal S, Smereka P, Harpaz N, et al. Characterization of immunologic defects in patients with common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) with intestinal disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17(1):251-9