Abstract

Demographic trends establish that older adults are the fastest growing segment of population, with over 19% of the population expected to be aged >65 years by 2030. As the risk for hematologic malignancies increases with age, it is imperative that our field continues to strive to individualize and manage risk and benefit in an aging population. While hematologic diseases are more common in the elderly, only a small minority of patients with hematological malignancy aged >65 years receive allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation, relative to the burden of disease in this population. In this editorial we explore some of the obstacles to transplantation, the rationale to consider the procedure in the older adult and ways that the stem cell consultative process can be individualized. Finally, we outline key areas where additional research is needed.

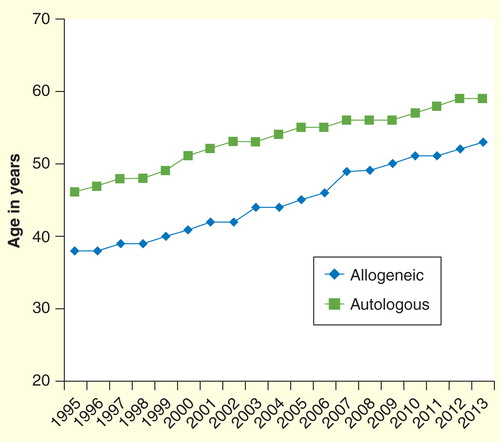

The incidence of hematologic malignancies increases with age, likely due to a constellation of factors including genomic instability, cumulative environmental exposure, stem-cell senescence and epigenetic drift. While potentially curative, treatment-related mortality (TRM) and morbidity from hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) remain challenging in patients of all ages. Concomitant medical problems increase treatment toxicity and age has historically been a marker for increased risk from myeloablative conditioning. These facts may explain the tendency to use chronological age to exclude patients from consideration for HCT. suggests that the median age of HCT recipients has increased over time; yet elderly patients undergoing transplantation remain a highly select cohort with only 1–5% of HCT in the major hematologic malignancies being performed in those aged >65 years, despite a higher incidence of hematological cancers in this population.

Figure 1. Median age of adult (>18 years) recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in the USA over time (1995–2013).

Clearly, not all patients are candidates for stem cell transplantation or will benefit from the procedure. However, age alone is an arbitrary, artificial and discriminatory barrier and can lead to denial of potentially curative therapy to those older patients who are biologically fit. Misconceptions about the conditioning regimens Citation[1], limitations imposed by third-party payers Citation[2], negative referral bias on the part of referring physicians, patients and patient families Citation[3,4] are generic obstacles and have also thwarted larger scale clinical trials in the older population; trials that might provide important guidance for care. In any therapeutic decision, both the physician and patient must carefully consider the risk posed by the underlying disease and the risk posed by the intervention. Unfortunately, without referral to a transplant center, this individualized decision process never has a chance to occur.

Acute leukemia & myelodysplastic syndrome

Emerging data point to the safety of transplantation in older adults. In patients with acute leukemia and over 60 years, the long-term disease control without HCT is exceedingly disappointing. Those above 55 years of age have historically been considered ineligible for allogeneic HCT. Yet, in large, retrospective studies, which naturally cannot control for selection bias, there does not appear to be a harmful effect of age on outcome. McClune et al. using the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) database, demonstrated that in acute myeloid leukemia, there was no statistically significant difference in non-relapse mortality, relapse risk or 2-year overall survival among patients aged 40–54, 55–59, 60–64 or over 64 years Citation[5]. Similar conclusions were reached by the European Bone Marrow Transplantation Group Citation[6] and by Sorror et al. Citation[7]. This latter study analyzed prospectively collected data from the Seattle consortium spanning the years 1998–2008. Among 372 patients aged 60–75 years receiving a non-myeloablative regimen, survival, graft-versus-host disease rates and toxicity were not impacted by chronological age. Rather, it was scores on the HCT-specific comorbidity index (HCT-CI) that correlated best with survival.

For years in the USA, a diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome was not an accepted indication for HCT by Medicare, the most common financial intermediary for those over 65 years. In a landmark 2011 decision, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services accepted a policy of coverage with evidence development by allowing allogeneic HCT coverage for myelodysplastic syndrome patients who enroll in specific trials or prospective CIBMTR data collection. These data will ensure that the benefits and risks of allogeneic HCT versus other alternatives in the Medicare-eligible population are analyzed in a prospective fashion enabling evidence development.

Lymphoma

The benefits of autologous HCT in subsets of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and Hodgkin lymphoma are well described. Currently, the near universal avoidance of total body irradiation-based conditioning, the employment of cytokine-mobilized peripheral blood grafts, systematic re-vaccination and post-HCT supportive care have led to reduction in TRM rates from roughly 10% to less than about 5%. As such, these improvements have translated into a greater deployment of autologous HCT in patients above 60–65 years of age Citation[8]. Contemporary registry data from the CIBMTR and the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation seem to validate this practice, with seemingly no increased TRM or compromised survival outcomes in patients >65 years of age undergoing auto-HCT in patients with aggressive NHL Citation[9], mantle cell lymphoma Citation[10], indolent lymphomas Citation[11] and Hodgkin lymphoma Citation[8].

Data on allografting in NHL mirror that in acute myeloid leukemia. A large CIBMTR analysis of older NHL patients (n = 1248) undergoing lower-intensity allogeneic HCT demonstrated that while advanced age had a modest adverse effect in patients older than 55 compared with those 40–54 years, outcomes of patients aged 55–64 and ≥65 years were equivalent, with no significant differences in TRM, disease relapse or survival outcomes Citation[12]. More importantly, additional data from this study demonstrated that a patient’s physiological age (i.e., his/her performance status and organ function) and availability of an HLA-matched donor are better predictors of transplantation outcomes than chronologic age.

Myeloma

The major trials establishing the survival advantage of autologous HCT in multiple myeloma (MM), conducted in the 1990s, involved patients <65 years of age, leaving HCT ineligible or ‘older’ patients to be treated with oral, melphalan-based induction therapy. As a result, autologous HCT, despite being covered by third-party providers in the USA (Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services), has not been widely employed in the majority of older patients with MM Citation[13]. Yet, in both prospective and retrospective studies, several groups have shown the feasibility and efficacy of HCT in patients older than 65 and even 70 years Citation[14,15]. A recent CIBMTR analysis involving more than 11,000 patients with MM suggested minimal TRM and a similar relapse rate after autologous HCT for myeloma in those >70 years compared with younger cohorts, though less than 10% were above the age of 70 years Citation[16].

Patient selection and melphalan dosing are critical in reducing morbidity. A lower intensity of melphalan conditioning is preferred by most centers (usually melphalan 140 mg/m2) and this did not result in inferior outcomes in the registry study. Performance status and HCT-CI are better correlated with survival than age Citation[17]. In the modern era of myeloma therapy, novel agent-based induction that preserves performance status and allows for stem cell harvest will perhaps result in greater proportion of older patients being able to avail the benefits of autologous HCT in myeloma Citation[18]. An approach of early stem-cell harvest and HCT after induction is preferred in older patients for whom a delayed HCT at relapse may not be a practical option due to changes in health status.

The HCT consultative process

Once the potential benefit of HCT is considered, we feel that a HCT consultation is necessary for a highly individualized assessment and discussion to determine candidacy and engagement in the clinical trial process. In potential transplant candidates, we carefully evaluate patient’s physiological health status, taking into account their medical comorbidities, functional status, disease type, remission status, frailty, nutritional status, mental health and availability of a suitable donor Citation[19]. This approach acknowledges the heterogeneity of chronological age, while utilizing a comprehensive geriatric assessment, which has been shown in a pilot study to capture a substantial amount of disability and frailty above and beyond performance scores and the HCT-CI Citation[20]. In our experience, in selected patients, with modern conditioning approaches, autologous and allogeneic HCT are realistic options for a significant proportion of patients aged 75–80 and 70–75 years, respectively.

Table 1. Patient selection: older individuals and transplantation.

One of the most interesting aspects of this decision-making is utility analysis by patients, their families and physicians as well as the interplay of societal biases. Actuarial analyses indicate that life expectancy at age 70 is an additional 14–16 years, while at 75 it is 11–13 years Citation[21], suggesting significant years of life lost if curative intent therapy were not offered. However, older patients and their families even in situations that warrant such therapy may hesitate to proceed to HCT on account of quality of life (QoL) concerns, perceived aggressiveness of treatments and negative perceptions of old age. Unfortunately, there are scarce data on post-transplant QoL in the older person, and even less on the factors that go into decision-making when an older patient faces these complex choices. The manner in which physicians communicate with older patients and their families about their disease, and how patients integrate into decision-making variables such as the years of potential life lost to illness, intensity of therapy, time in hospital and QoL issues are critical topics that need to be explored systematically.

With over 19% of the population expected to be aged >65 years by 2030, an understanding of how to individualize treatment risk and benefit in this population is imperative. The age of therapeutic nihilism in the ‘elderly’ is giving way to realistic risk assessment and careful communication of risk–benefit calculations.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Champlin R. Reduced intensity allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation is an established standard of care for treatment of older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2013;26:297-300

- National coverage determination (NCD) for stem cell transplantation (110.8.1), centers for medicaid and medicare services. Available from: www.cms.gov; [Last accessed 31 January 2014]

- Rini C, Manne S, DuHamel KN, et al. Mothers’ perceptions of benefit following pediatric stem cell transplantation: a longitudinal investigation of the roles of optimism, medical risk, and sociodemographic resources. Ann Behav Med 2004;28:132-41

- Estey E, de Lima M, Tibes R, et al. Prospective feasibility analysis of reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). Blood 2007;109:1395-400

- McClune BL, Weisdorf DJ, Pedersen TL, et al. Effect of age on outcome of reduced-intensity hematopoietic cell transplantation for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission or with myelodysplastic syndrome. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1878-87

- Lim Z, Brand R, Martino R, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for patients 50 years or older with myelodysplastic syndromes or secondary acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:405-11

- Sorror ML, Sandmaier BM, Storer BE, et al. Long-term outcomes among older patients following nonmyeloablative conditioning and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for advanced hematologic malignancies. JAMA 2011;306:1874-83

- McCarthy PL Jr, Hahn T, Hassebroek A, et al. Trends in use of and survival after autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation in north america, 1995-2005: Significant improvement in survival for lymphoma and myeloma during a period of increasing recipient age. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2013;19:1116-23

- Jantunen E, Canals C, Rambaldi A, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation in elderly patients > or = 60 years with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: an analysis based on data in the european blood and marrow transplantation registry. Haematologica 2008;93:1837-42

- Jantunen E, Canals C, Attal M, et al. Autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with mantle cell lymphoma beyond 65 years of age: a study from the european group for blood and marrow transplantation (EBMT). Ann Oncol 2012;23(1):166-71

- Lazarus HM, Carreras J, Boudreau C, et al. Influence of age and histology on outcome in adult non-hodgkin lymphoma patients undergoing autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT): A report from the center for international blood & marrow transplant research (CIBMTR). Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2008;14:1323-33

- McClune BL, Ahn KW, Wang HL, et al. Allotransplantation for patients age ≥40 years with non-hodgkin lymphoma: encouraging progression-free survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014. [Epub ahead of print]

- Costa LJ, Nista EJ, Buadi FK, et al. Prediction of poor mobilization of autologous CD34+ cells with growth factor in multiple myeloma patients: Implications for risk-stratification. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014;20:222-8

- Bashir Q, Shah N, Parmar S, et al. Feasibility of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant in patients aged ≥70 years with multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma 2012;53:118-122

- Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Petrucci MT, et al. Intermediate-dose melphalan improves survival of myeloma patients aged 50 to 70: results of a randomized controlled trial. Blood 2004;104:3052-7

- Sharma M, Zhang M, Zhong X, et al. Multiple myeloma (MM) in older (>70 year) patients - similar benefit from autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AHCT) compared with younger patients (Abstract). Blood 2013;122(21):416

- Saad A, Mahindra A, Zhang MJ, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplant comorbidity index is predictive of survival after autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation in multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014;20(3):402-8. e1

- Merz M, Neben K, Raab et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for elderly patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma in the era of novel agents. Ann Oncol 2014;25:189-95

- Hamadani M, Craig M, Awan FT, et al. How we approach patient evaluation for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2010;45:1259-68

- Muffly LS, Boulukos M, Swanson K, et al. Pilot study of comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) in allogeneic transplant: CGA captures a high prevalence of vulnerabilities in older transplant recipients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2013;19:429-34

- Social security administration, US actuarial. life tables. Available from: www.ssa.gov/OACT/STATS/table4c6.html; Last accessed 31 January 2014