Abstract

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic disease characterized by chronic or recurrent abscesses, sinus tracts and scarring of apocrine gland-bearing skin. Key areas of different treatment options for hidradenitis suppurativa have been addressed and outlined in this review. Management should be individualized according to the extent of the disease, frequency of exacerbation and risk status. The treatment consists of medical (local or systemic), surgical and laser therapy. New treatments, such as TNF-α inhibitors, have provided clinicians with more options against this difficult disease.

Medscape: Continuing Medical Education Online

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Medscape, LLC and Expert Reviews Ltd. Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians. Medscape, LLC designates this educational activity for a maximum of 0.5 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test and/or complete the evaluation at http://www.medscapecme.com/journal/expertderm; (4) view/print certificate.

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants should be able to:

• Recognize the typical presentation and appropriately evaluate patients with suspected hidradenitis suppurativa, and construct an effective treatment strategy for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa that appropriately incorporates surgical management

Financial & competing interests disclosure

CME AUTHOR: Charles P Vega, MD,Associate Professor; Residency Director, Department of Family Medicine, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA

Disclosure:Charles P Vega, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

EDITOR:Elisa Manzotti,Editorial Director, Future Science Group.Disclosure:Elisa Manzotti has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

AUTHORS

Shiva Yazdanyar, MD,Department of Dermatology, Roskilde HospitalKøgevej, Roskilde, Denmark

Disclosure:Shiva Yazdanyar has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Gregor BE Jemec, MD,Department of Dermatology, Roskilde HospitalKøgevej, Roskilde, Denmark

Disclosure:Gregor BE Jemec has has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received unrestricted grants for clinical research from: UpJohn; Abbott Laboratories; Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc. Acted as principal investigator in hidradenitis suppurativa studies for: Abbott Laboratories Served as a member of advisory boards for: Abbott Laboratories; Pfizer Inc.; MSD/Schering Plough Other: member of the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation Board

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a disease characterized by chronic recurrent inflamed and suppurating lesions located in apocrine gland-bearing skin, for example that of the axillae and groin Citation[1–3]. A consensus definition was adopted by the second congress organized by the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation (San Francisco, CA, USA, March 2009) Citation[101]: “HS is a chronic, inflammatory, recurrent, debilitating, skin follicular disease that usually presents after puberty with painful deep-seated, inflamed lesions in the apocrine gland-bearing area of the body, most commonly, the axillary, inguinal and anogenital regions”.

The definition includes only clinical features, with no biological or pathological test available to help. Diagnostic criteria (adopted by the second congress organized by the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation) relies on the presence of:

• Typical lesions, specifically deep-seated painful nodules: ‘blind boils’ in early lesions; abscesses, draining sinus, bridged scars and ‘tombstone’ open comedones in secondary lesions

• Typical topography, specifically, axillae, groin, perineal and perianal region, buttocks, infra- and inter-mammary folds;

• Chronicity and recurrences Citation[101].

These three criteria must be met for establishing the diagnosis. Based on these clinical criteria, the diagnosis is comparatively uncomplicated and a good diagnostic accuracy can be obtained through the simple question: have you had recurrent boils during the last 6 months? If yes, have these been located to the armpits or groin? Citation[4].

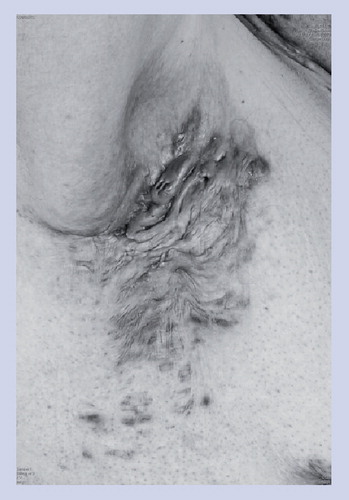

The clinical presentation of HS is classified into primary and secondary lesions Citation[5]. The primary lesions are solitary painful nodules persisting for weeks or months. These early lesions are not characteristic for HS, and are frequently considered as boils or abscesses. The secondary lesions result from repetitive attacks, leading to chronic suppurative sinus and scar formation, which persist for months or years.

The main differential diagnoses of HS are abscess, carbuncles, furunculosis, infected Bartholin’s gland, infected or inflamed epidermal cysts, lymphogranuloma venereum, scrofuloderma, actinomycosis, developmental fistulae, nodular acne and pilonidal cyst and cutaneous manifestation of Crohn’s disease Citation[3,5].

The disease is not uncommon, with a prevalence in the general population of approximately 1% Citation[6–9]. Although cases have been described in children, the disease most often appears after puberty and is rare among the aged. It causes considerable morbidity, both as seen through an associated increase in sick leave, as well as through much reduced quality of life Citation[10–13]. The prognosis of HS is poor, as the hallmark of HS is the chronicity.

The main complications of HS include: acute infections Citation[3,14,15]; lymphatic obstruction and lymphedema Citation[3]; squamous cell carcinoma Citation[3,16]; fistula formation into urethra, bladder or peritoneum Citation[3,17]; anemia Citation[18]; chronic malaise; and depression Citation[3]. Moreover, a retrospective study with more than 2000 cases found a 50% increased risk of overall incidence of malignancy in HS patients Citation[19].

The etiology of the disease is unknown. Several hypotheses have been proposed Citation[2], although conclusive evidence is, as yet, lacking. It has been suggested that structural anomalies of the pilosebaceous unit may be responsible under conditions of physical stress and strain of the skin; that the disease represents an immunological dysregulation within the hair follicle; and that scarring and migration of stem-cell-like cells may be responsible for the development of characteristic lesions. Nevertheless, the world literature on this disease is limited, and it remains an orphan disease, a secret scourge of the patients and an unmet challenge to physicians Citation[20].

A number of risk factors have been suggested. By performing a case–control study of 302 HS patients, Revuz et al. confirmed that smoking and overweight are the two main nongenetic factors associated with HS Citation[9]. The rate of active smokers was found to be significantly higher (>70%) among cases with HS compared with controls, and the odds ratio for risk of HS was estimated to be 1.12 (95% CI: 1.08–1.15) for each increase of one unit of BMI. Bacterial infections have been regarded as playing an important role in the clinical manifestation of HS, although they are most likely not the initial causative factor. Routine cultures in HS patients are often negative, but numerous bacteria have been recovered from lesions of HS, for example streptococci, staphylococci, gram-negative rods and anaerobic bacteria Citation[21,22]. Finally, a series of observations, such as premenstrual flare-ups, female preponderance, frequent occurrence after menarche and improvement during pregnancy have pointed towards a role of hormonal factors in the etiology of HS Citation[1,6,23–26]. However, the absence of clinical signs of virilism and the normal blood level of androgens rules out a key role of hyperandrogenism Citation[6,23,25,27].

Severity assessment of HS

Clinically relevant staging and disease severity assessment are prerequisites for the development of evidence-based treatments. Staging of HS is carried out through the use of the Hurley stages, describing the degree of inflammation and fibrosis Citation[28]:

• Hurley stage I – abscess formation (single or multiple) without sinus tracts and cicatrization;

• Hurley stage II – single or multiple, widely separated recurrent abscesses with tract formation and cicatrization;

• Hurley stage III – multiple interconnected tracts and abscesses throughout an entire area (Box 1).

This relevant staging system is, however, not sufficiently dynamic for the description of treatment outcomes. The Sartorius score, which is composed of counts of involved regions, nodules and sinus tracts, has therefore been proposed for the severity assessment (Box 2)Citation[29]. It is based on the salient clinical features of the disease, and allows a more dynamic description of disease severity. Its main restriction is that it is primarily designed to document the treatment outcomes following surgery, and, therefore, may not adequately reflect changes following medical therapy, which does not completely remove lesions, but primarily controls inflammation. Useful modifications have, therefore, been proposed to the original Sartorius score Citation[3,30].

Disease severity scores that are exclusively based on physicians’ assessment of morphological features of a disease may not adequately reflect the disease’s impact on the patient. In particular, high-impact diseases, such as HS, involve significant soreness and loss of quality of life Citation[10,12,13], which suggests that physician assessment may benefit from additional patient-supplied data on, for example, current soreness, number of flares since last visit or general dermatologic quality of life tools, such as the Dermatology Life Quality Index, Skindex or other validated questionnaires.

Treatments

General interventions

Smoking and overweight are the two main risk factors associated with HS Citation[5,31]. The patients should therefore be encouraged to stop smoking and/or undertake a weight loss program as nonpharmological therapies.

Medical therapies

Topical options

In one randomized controlled trial, patients were treated with either topical clindamycin or a placebo Citation[32]. The number of abscesses, inflammatory nodules and pustules was significantly less in the clindamycin group than in the placebo group at each monthly evaluation. In another randomized controlled trial, the topical clindamycin was found to be as effective as systemic tetracycline (500 mg twice daily for 3 months) in the treatment of HS Citation[33].

Resorcinol peels have traditionally been used for the treatment of follicular occlusion disease, and were extensively used in acne prior to the development of antibiotics and retinoids. There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that the use of 15% resorcinol peels may be of use to patients with HS Citation[34]. The effect appears to be early spontaneous draining and resolution of lesions. The main effect of the treatment is, therefore, patient empowerment, as it provides patients with a certain degree of control over the flares of the disease. However, additional studies are needed to establish the exact role of this treatment modality.

Intralesional triamcinolone in small doses of 2–5 mg is often useful in the control of single lesions. The intralesional therapy represents an intermediate stage between medical and surgical therapy Citation[5]. The treatment is empirically developed and the published literature is correspondingly scant, with no formal trials having been carried out. However, this does not detract from the advantages of the technique, which has been in use for decades. It is also one of the first examples of a nonantibiotic therapy that has gained some prominence, and thereby an early suggestion that the underlying disease mechanisms are more complex than simple infection.

Systemic options

It has been suggested that folliculitis decalvans and HS are related diseases, based on the histopathology of the lesions Citation[5]. In 2006, Mendonca and Griffiths introduced a combination therapy for folliculitis decalvans using clindamycin and rifampicin Citation[35]. This treatment has been anecdotally reported to be successful in HS, and two case series have described the positive effects of this treatment in a total of 190 patients Citation[36,37]. Treatment is originally prescribed using clindamycin 300 mg twice-daily and rifampicin 300 mg twice-daily for at least 3 months, but reported cases suggest that this may not be the only effective dosage Citation[37]. These observations await further confirmation within a randomized controlled trial comparing combination treatment with, for example, tetracycline monotherapy. The treatment may potentially have associated gastrointestinal side effects limiting its use. In the published cases, 38% reported side effects and 26% stopped treatment due to the side effects. Specific dose-finding studies and pharmacological developments in the drug delivery are therefore necessary to avoid drop outs due to side effects.

In order to examine the effect of anti-androgen therapy, in one double-blind, controlled, cross-over study, cyproterone actetate associated with estrogens was compared with ethinyloestradiol, a ‘classical contraceptive pill’ Citation[38]. The results showed improvements in disease activity with both treatments, and no difference was observed between the two products.

Based on the clinical confusion regarding the relationship between HS and acne, isotretinoin was expected by many to be an effective treatment option for HS, and is often tried. However, the available data suggests this is not the case. Boer et al. performed a retrospective chart review of 68 HS patients treated with isotretinoin, but unfortunately found no significant effect of the drug Citation[39]. These results were confirmed by another study based on patients’ ‘outcome assessment’ Citation[40].

Systemic immunosuppressants are generally useful in the treatment of HS Citation[5]. The concept of HS as an inflammatory disease allows the use of traditional immunosuppressants in the treatment of more severe cases Citation[41]. Systemic steroids are often used with initial benefit through a reduction in inflammation and pain, although formal studies are also lacking here. They may be useful in acute exacerbations, but because of the high risk of flares when dosage is reduced and the risk of systemic side effects, it should only be used in shorter periods of time and/or in conjunction with other therapies Citation[42,43]. Limited evidence suggests that cyclosporine is useful Citation[44,45], and in the experience of the authors similar effects can be obtained using systemic corticosteroids Citation[46]. The immune regulation achieved with these drugs offers similar disease control in HS as in other inflammatory skin diseases, and is supported by histological studies suggesting an early role for lymphocytes and activation of innate immune responses Citation[47]. In contrast, the use of methotrexate appears to have very limited effect on the disease activity Citation[48].

Dapsone has partial antibiotic and partial immune-regulating effects. Case series have suggested that the drug may be useful in the treatment of HS Citation[49,50]. The exact mechanism of action is not described, but in histological studies of HS the neutrophilocyte is a late-comer in the lesions, suggesting that either the drug is only suited to treat established lesions, or that another mechanism is involved.

In recent years, biological agents, such as TNF-α inhibitors, have produced favorable outcomes in HS Citation[5,51,52]. TNF-α is a pleiotropic pro-inflammatory cytokine produced primarily by monocytes and macrophages. When TNF-α is activated, it induces a cascade of inflammatory reactions that leads to excessive inflammation. Therefore, inhibition of TNF-α may play an important role in the therapy of a number of disparate inflammatory disorders. Matusiak et al. performed the first study demonstrating elevated levels of TNF-α in a HS patient Citation[53]. Infliximab was the first TNF-α inhibitor shown to have a beneficial effect in HS patients with associated Crohn’s disease Citation[52]. In a recently published review, the authors found 20 studies with a total of 52 HS patients examining the effect of infliximab Citation[52]. Improvement with infliximab was reported in 45 out of 52 patients. However, only 17 patients showed long-term improvement. The initial favorable outcome of infliximab treatment of HS has recently been confirmed in a randomized controlled study, suggesting that the majority of patients experience a significant improvement during therapy. Long-term effects were also studied in a small group, where two out of five patients experienced long-term remission after infliximab therapy Citation[51]. The treatment has been associated with significant adverse events, including lupus-like reactions, hypersensitivity reactions, abdominal pain secondary to colon cancer, multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction block, TB and anaphylactic shock Citation[16].

Etanercept (Enbrel®) and adalimumab (Humira®) are other TNF-α inhibitors that have recently been documented as useful for HS treatment, with no severe side effects reported so far Citation[16,52,54,55]. Switching between TNF-α inhibitors has been reported to be successful in cases of treatment failure Citation[56].

Currently, the level of evidence describing the effects of TNF-α inhibitors in HS is limited to a few small trials and cases, and further studies therefore need to be conducted to determine the effect, side effects and long-term evaluation of these drugs. In particular, the reports of the long-term effect of these treatments are of great interest Citation[57,58].

Surgery & laser therapies

Surgery options

Surgery is the principal treatment for chronic, relapsing and severe HS. A large degree of the literature on surgery for HS is associated with methods of closure following removal of lesions. Targeted destruction of HS lesions has been used extensively in the management of HS, although it is conceptually difficult as the disease is generalized from the onset, as can be seen from recurrences seen in regions not treated surgically or in ultrasound scans of seemingly uninvolved skin Citation[59]. However, many procedures have been tried, and while many are effective in the hands of a skilled operator, the effects are variable and in rare cases questionable. Localized surgery has traditionally been carried out using a technique called marsupialization, which involves the opening of sinus tracts without their removal Citation[60]. This in theory allows the re-epithelialization of the lesion using the epithelial lining of the sinus tract itself in secondary intention healing. It is generally described as an efficient technique, although there appears to be specific studies describing outcomes. By contrast, there is a body of literature describing the use of localized excisions in the treatment of HS Citation[61–65]. The general consensus appears to be that the wider the excision the better the result, and it has been suggested that healing by secondary intention results in superior outcomes. However, the formal evidence in support of this is weak. The addition of gentamycin to the surgical wound does not improve the long-term results Citation[66].

Laser therapy

Cutting lasers (CO2 and Nd:Yag) have been used in the treatment of HS Citation[67–73]. The advantages are the ability to operate without hemorrhage and with a complete overview of the tissue, which allows the surgeon to adopt a technique not unlike Mohs micrographic surgery, only without the micrographic component. The tissue is evaporated in layers from the surface of the skin using a CO2 laser. Progress is visually controlled and makes it possible for the operator to remove all abnormal tissue, while keeping the postoperative wound as small as possible. The technique is suitable for patients with an intermediate disease severity, and is not associated with severe side effects, although the postoperative healing period may be long depending on the extent of the lesions treated. However, like all surgical techniques, laser surgery remains an operator-dependent treatment modality.

Other treatments

Oral zinc salts, when used in high doses (90 mg of zinc gluconate), have been shown in short open series to have a beneficial effect on HS, mainly in patients with Hurley stage I and II Citation[74].

The use of photodynamic therapy has been suggested, although initial case reports have not been substantiated by further open studies Citation[60,75,76]. Similarly, cryotherapy has been used, but due to the fibrotic and deep nature of lesions it appears to be associated with significant side effects, making this treatment option less attractive Citation[77].

Radiotherapy, which was extensively used in the past, has also been suggested as an effective treatment option for HS, in particular for the early lesions. Numerous patient series have shown good results with doses up to 8 Gy. However, because this treatment is a potential carcinogen, it should be considered with caution Citation[78].

A nonablative radiofrequency device has in one case report been shown to be successful Citation[79].

Botulinum toxin injections have been reported in a single case report, claiming good results for the treatment of HS Citation[80]. The patient was treated with a series of intradermal injections during a single treatment session and the inflammatory lesions resolved for 10 months following the treatment. Further studies are obviously necessary to confirm this observation.

General treatment suggestions & case management

Case management varies with the severity of disease. Early disease with little or no scarring may respond to topical treatment with clindamycin applied twice-daily during flares Citation[32]. If only single lesions appear, early localized surgery or medical treatment with topical resorcinol or intralesional triamcinolone may be considered Citation[5].

With more widespread or fibrotic lesions systemic treatment is recommended using either tetracyclines Citation[33] or a combination of clindamycin and rifampicin for 3-month periods Citation[36,37]. When the disease is under control, medical treatment can be supplemented by surgery, either as cold steel excisions or laser evaporation, depending on the availability of a sufficiently powerful laser and a skilled operator Citation[5].

With larger more fibrotic lesions, extensive surgery is currently the only available therapy, and where this is technically impossible the patients are managed through judicious use of systemic immunosupressants such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine or TNF-α inhibitors .

Expert commentary

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a complex disease that is often debilitating to patients, and although our knowledge has considerably increased in the last decade, many aspects require continued or intensified attention from the scientific community. In particular, a better understanding of the disease’s etiology and pathogenesis will allow a more evidence-based, targeted therapeutic strategy. Key areas of different treatments options for HS have been addressed and outlined in this article. Management of HS must be individualized according to the extent of the disease, frequency of exacerbation, risk status and goal of the patient. Both medical (topical and systemic), surgical and laser approaches should be considered before initiating treatment.

Five-year view

Within the next 5 years, currently ongoing trials will be completed and the role of TNF-α inhibitors will be much better established in the treatment of HS. At the same time, it is expected that a broad screening for alternative therapies will continue with the publication of case series involving pharmacological anti-inflammatory drugs and antibiotics, as well as topical drugs that may affect immunity and microbiology locally. It is unlikely that any medical intervention will be curative in any but the mildest cases, and a continued development of surgical methods is therefore also to be expected. However, surgery is not always curative either, and a multimodal approach with treatment of flares, surgical interventions to reduce the burden of diseased tissue and symptomatic control of the disease is expected to continue in the foreseeable future, unless a major breakthrough is made regarding the etiology of the disease.

Table 1. Treatment suggestions according to Hurley stage.

Box 1. Hurley’s classification.

Stage I

• Abscess formation, single or multiple without sinus tracts and cicatrization/scarring

Stage II

• Recurrent abscesses with sinus tracts and scarring

• Single or multiple widely separated lesions

Stage III

• Diffuse or almost diffuse involvement or multiple interconnected tracts and abscesses

Box 2. Sartorius score.

Anatomical region involved (three points per region involved)

• Axilla

• Groin

• Gluteal

• Intramammary left/right

• Other

Number and scores of lesions

• 2 points for abscesses/nodules

• 4 points for fistulae

• 1 point for scars

• 1 point for others

The longest distance between two relevant lesions

• 2 points if <5 cm

• 4 points if <10 cm

• 8 points if >10 cm

Are all lesions separated by normal skin?

• 0 points if yes

• 6 points if no

Key issues

• The disease is multifocal and often subclinically present in the predisposed regions, and a range of treatments should therefore be used according to the individual patient.

• General interventions include cessation of smoking and weight loss.

• Topical treatments include topical clindamycin, intralesional triamcinolone and resorcinol.

• Systemic medical interventions include systemic steroids, antibiotics (clindamycin–rifampicin), cyclosporine and dapsone.

• TNF-α inhibitors appear useful, and may in some cases induce longer periods of remission.

• Surgical interventions include incision and local or radical excision.

• Laser therapy includes CO2 laser excision.

• Treatments can be combined sequentially or simultaneously depending on the severity of the disease.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Dr Jemec has received unrestricted grants for clinical research from UpJohn, Abbott and Wyeth; has acted as principal investigator in hidradenitis suppurativa studies for Abbott; and is a member of advisory boards for Abbott, Pfizer and MSD-Schering Plough. In addition he is a member of the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation Board. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Cutan. Med. Surg.7(1), 47–56 (2003).

- Kurzen H, Kurokawa I, Jemec GB et al. What causes hidradenitis suppurativa? Exp. Dermatol.17(5), 455–456 (2008).

- Revuz J. Hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol.23(9), 985–998 (2009).

- Esmann S, Dufour DN, Jemec GB. Questionnaire based diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa-specificity, sensitivity and positive predictive value of specific diagnostic questions. Br. J. Dermatol. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2133. 2010.09773.x (2010) (Epub ahead of print).

- Jemec GB, Revuz J, Leyden J. Hidradenitis Suppurativa. 1st Edition. Springer, NY, USA (2006).

- Jemec GB. The symptomatology of hidradenitis suppurativa in women. Br. J. Dermatol.119(3), 345–350 (1988).

- Jemec GB, Heidenheim M, Nielsen NH. A case–control study of hidradenitis suppurativa in an STD population. Acta Derm. Venereol.76(6), 482–483 (1996).

- Jemec GB, Heidenheim M, Nielsen NH. The prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa and its potential precursor lesions. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.35(2 Pt 1), 191–194 (1996).

- Revuz JE, Canoui-Poitrine F, Wolkenstein P et al. Prevalence and factors associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from two case–control studies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.59(4), 596–601 (2008).

- von der Werth JM, Jemec GB. Morbidity in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br. J. Dermatol.144(4), 809–813 (2001).

- Jemec GB, Heidenheim M, Nielsen NH. Hidradenitis suppurativa – characteristics and consequences. Clin. Exp. Dermatol.21(6), 419–423 (1996).

- Solarski ST. Living with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol. Nurs.16(5), 447–449 (2004).

- Wolkenstein P, Loundou A, Barrau K, Auquier P, Revuz J. Quality of life impairment in hidradenitis suppurativa: a study of 61 cases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.56(4), 621–623 (2007).

- Anderson BB, Cadogan CA, Gangadharam D. Hidradenitis suppurativa of the perineum, scrotum, and gluteal area: presentation, complications, and treatment. J. Natl Med. Assoc.74(10), 999–1003 (1982).

- Russ E, Castillo M. Lumbosacral epidural abscess due to hidradenitis suppurativa. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol.178(3), 770–771 (2002).

- Alikhan A, Lynch PJ, Eisen DB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a comprehensive review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.60(4), 539–561 (2009).

- Wiltz O, Schoetz DJ Jr, Murray JJ, Roberts PL, Coller JA, Veidenheimer MC. Perianal hidradenitis suppurativa. The Lahey Clinic experience. Dis. Colon Rectum33(9), 731–734 (1990).

- Tennant F Jr, Bergeron JR, Stone OJ, Mullins JF. Anemia associated with hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch. Dermatol.98(2), 138–140 (1968).

- Lapins J, Ye W, Nyren O, Emtestam L. Incidence of cancer among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch. Dermatol.137(6), 730–734 (2001).

- von der Werth JM, Williams HC. The natural history of hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol.14(5), 389–392 (2000).

- Jemec GB, Faber M, Gutschik E, Wendelboe P. The bacteriology of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology193(3), 203–206 (1996).

- Lapins J, Jarstrand C, Emtestam L. Coagulase-negative staphylococci are the most common bacteria found in cultures from the deep portions of hidradenitis suppurativa lesions, as obtained by carbon dioxide laser surgery. Br. J. Dermatol.140(1), 90–95 (1999).

- Barth JH, Layton AM, Cunliffe WJ. Endocrine factors in pre- and postmenopausal women with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br. J. Dermatol.134(6), 1057–1059 (1996).

- Harrison BJ, Kumar S, Read GF, Edwards CA, Scanlon MF, Hughes LE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence for an endocrine abnormality. Br. J. Surg.72(12), 1002–1004 (1985).

- Harrison BJ, Read GF, Hughes LE. Endocrine basis for the clinical presentation of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br. J. Surg.75(10), 972–975 (1988).

- Mortimer PS, Dawber RP, Gales MA, Moore RA. Mediation of hidradenitis suppurativa by androgens. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.)292(6515), 245–248 (1986).

- Mortimer PS, Lunniss PJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa. J. R. Soc. Med.93(8), 420–422 (2000).

- Hurley HJ. Axillary hyperhidrosis, apocrine bromhidrosis, hidradenitis suppurativa and familial benign pemphigus. Surgical approach. Dermatologic surgery. Principles and practice. Roenigk RK, Roenigk HH Jr (Eds). Marcel Dekker Inc., NY, USA, 623–645 (1996).

- Sartorius K, Lapins J, Emtestam L, Jemec GB. Suggestions for uniform outcome variables when reporting treatment effects in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br. J. Dermatol.149(1), 211–213 (2003).

- Sartorius K, Emtestam L, Jemec GB, Lapins J. Objective scoring of hidradenitis suppurativa reflecting the role of tobacco smoking and obesity. Br. J. Dermatol.161(4), 831–839 (2009).

- Konig A, Lehmann C, Rompel R, Happle R. Cigarette smoking as a triggering factor of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology198(3), 261–264 (1999).

- Clemmensen OJ. Topical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with clindamycin. Int. J. Dermatol.22(5), 325–328 (1983).

- Jemec GB, Wendelboe P. Topical clindamycin versus systemic tetracycline in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.39(6), 971–974 (1998).

- Boer J, Jemec GB. Resorcinol peels as a possible self-treatment of painful nodules in hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin. Exp. Dermatol.35(1), 36–40 (2010).

- Mendonca CO, Griffiths CE. Clindamycin and rifampicin combination therapy for hidradenitis suppurativa. Br. J. Dermatol.154(5), 977–978 (2006).

- Gener G, Canoui-Poitrine F, Revuz JE et al. Combination therapy with clindamycin and rifampicin for hidradenitis suppurativa: a series of 116 consecutive patients. Dermatology219(2), 148–154 (2009).

- van der Zee HH, Boer J, Prens EP, Jemec GB. The effect of combined treatment with oral clindamycin and oral rifampicin in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology219(2), 143–147 (2009).

- Mortimer PS, Dawber RP, Gales MA, Moore RA. A double-blind controlled cross-over trial of cyproterone acetate in females with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br. J. Dermatol.115(3), 263–268 (1986).

- Boer J, van Gemert MJ. Long-term results of isotretinoin in the treatment of 68 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.40(1), 73–76 (1999).

- Soria A, Canoui-Poitrine F, Wolkenstein P et al. Absence of efficacy of oral isotretinoin in hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective study based on patients’ outcome assessment. Dermatology218(2), 134–135 (2009).

- Kipping HF. How I treat hidradenitis suppurativa. Postgrad. Med.48(3), 291–292 (1970).

- Camisa C, Sexton C, Friedman C. Treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with combination hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian and adrenal suppression. A case report. J. Reprod. Med.34(8), 543–546 (1989).

- Fearfield LA, Staughton RC. Severe vulval apocrine acne successfully treated with prednisolone and isotretinoin. Clin. Exp. Dermatol.24(3), 189–192 (1999).

- Buckley DA, Rogers S. Cyclosporin-responsive hidradenitis suppurativa. J. R. Soc. Med.88(5), 289P–290P (1995).

- Rose RF, Goodfield MJ, Clark SM. Treatment of recalcitrant hidradenitis suppurativa with oral ciclosporin. Clin. Exp. Dermatol.31(1), 154–155 (2006).

- Danto LJ. Preliminary studies of the effect of hydrocortisone on hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Invest. Dermatol.31, 299–300 (1958).

- Boer J, Weltevreden EF. Hidradenitis suppurativa or acne inversa. A clinicopathological study of early lesions. Br. J. Dermatol.135(5), 721–725 (1996).

- Jemec GB. Methotrexate is of limited value in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin. Exp. Dermatol.27(6), 528–529 (2002).

- Hofer T, Itin PH. [Acne inversa: a dapsone-sensitive dermatosis]. Hautarzt52(10 Pt 2), 989–992 (2001).

- Kaur MR, Lewis HM. Hidradenitis suppurativa treated with dapsone: a case series of five patients. J. Dermatolog. Treat.17(4), 211–213 (2006).

- Grant A, Gonzalez T, Montgomery MO, Cardenas V, Kerdel FA. Infliximab therapy for patients with moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.62(2), 205–217 (2010).

- Haslund P, Lee RA, Jemec GB. Treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitors. Acta Derm. Venereol.89(6), 595–600 (2009).

- Matusiak L, Bieniek A, Szepietowski JC. Increased serum tumour necrosis factor-α in hidradenitis suppurativa patients: is there a basis for treatment with anti-tumour necrosis factor-α agents? Acta Derm. Venereol.89(6), 601–603 (2009).

- Moul DK, Korman NJ. The cutting edge. Severe hidradenitis suppurativa treated with adalimumab. Arch Dermatol.142(9), 1110–1112 (2006).

- Sotiriou E, Apalla Z, Vakirlis E, Ioannides D. Efficacy of adalimumab in recalcitrant hidradenitis suppurativa. Eur. J. Dermatol.19(2), 180–181 (2009).

- Poulin Y. Successful treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with infliximab in a patient who failed to respond to etanercept. J. Cutan. Med. Surg.13(4), 221–225 (2009).

- Mekkes JR, Bos JD. Long-term efficacy of a single course of infliximab in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br. J. Dermatol.158(2), 370–374 (2008).

- Pelekanou A, Kanni T, Savva A et al. Long-term efficacy of etanercept in hidradenitis suppurativa: results from an open-label phase II prospective trial. Exp. Dermatol. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0625. 2009.00967.x (2009) (Epub ahead of print).

- Wortsman X, Jemec GB. Real-time compound imaging ultrasound of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol. Surg.33(11), 1340–1342 (2007).

- Rose RF, Stables GI. Topical photodynamic therapy in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther.5(3), 171–175 (2008).

- Bordier-Lamy F, Palot JP, Vitry F, Bernard P, Grange F. [Surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective study of 93 cases]. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol.135(5), 373–379 (2008).

- Harrison BJ, Mudge M, Hughes LE. Recurrence after surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.)294(6570), 487–489 (1987).

- Jemec GB. Effect of localized surgical excisions in hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.18(5 Pt 1), 1103–1107 (1988).

- Ritz JP, Runkel N, Haier J, Buhr HJ. Extent of surgery and recurrence rate of hidradenitis suppurativa. Int. J. Colorectal Dis.13(4), 164–168 (1998).

- Rompel R, Petres J. Long-term results of wide surgical excision in 106 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol. Surg.26(7), 638–643 (2000).

- Buimer MG, Ankersmit MF, Wobbes T, Klinkenbijl JH. Surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with gentamicin sulfate: a prospective randomized study. Dermatol. Surg.34(2), 224–227 (2008).

- Bratschi HU, Altermatt HJ, Dreher E. [Therapy of suppurative hidradenitis using the CO2-laser. Case report and literature review]. Schweiz. Rundsch. Med. Prax.82(35), 941–945 (1993).

- Dalrymple JC, Monaghan JM. Treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with the carbon dioxide laser. Br. J. Surg.74(5), 420 (1987).

- Finley EM, Ratz JL. Treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with carbon dioxide laser excision and second-intention healing. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.34(3), 465–469 (1996).

- Lapins J, Marcusson JA, Emtestam L. Surgical treatment of chronic hidradenitis suppurativa: CO2 laser stripping-secondary intention technique. Br. J. Dermatol.131(4), 551–556 (1994).

- Lapins J, Sartorius K, Emtestam L. Scanner-assisted carbon dioxide laser surgery: a retrospective follow-up study of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.47(2), 280–285 (2002).

- Madan V, Hindle E, Hussain W, August PJ. Outcomes of treatment of nine cases of recalcitrant severe hidradenitis suppurativa with carbon dioxide laser. Br. J. Dermatol.159(6), 1309–1314 (2008).

- Tierney E, Mahmoud BH, Hexsel C, Ozog D, Hamzavi I. Randomized control trial for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with a neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet laser. Dermatol. Surg.35(8), 1188–1198 (2009).

- Brocard A, Knol AC, Khammari A, Dreno B. Hidradenitis suppurativa and zinc: a new therapeutic approach. A pilot study. Dermatology214(4), 325–327 (2007).

- Gold M, Bridges TM, Bradshaw VL, Boring M. ALA-PDT and blue light therapy for hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Drugs Dermatol.3(1 Suppl.), S32–S35 (2004).

- Sotiriou E, Apalla Z, Maliamani F, Ioannides D. Treatment of recalcitrant hidradenitis suppurativa with photodynamic therapy: report of five cases. Clin. Exp. Dermatol.34(7), e235–e236 (2009).

- Bong JL, Shalders K, Saihan E. Treatment of persistent painful nodules of hidradenitis suppurativa with cryotherapy. Clin. Exp. Dermatol.28(3), 241–244 (2003).

- Frohlich D, Baaske D, Glatzel M. [Radiotherapy of hidradenitis suppurativa – still valid today?]. Strahlenther. Onkol.176(6), 286–289 (2000).

- Iwasaki J, Marra DE, Fincher EF, Moy RL. Treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with a nonablative radiofrequency device. Dermatol. Surg.34(1), 114–117 (2008).

- O’Reilly DJ, Pleat JM, Richards AM. Treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with botulinum toxin A. Plast. Reconstr. Surg.116(5), 1575–1576 (2005).

Website

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation www.hs-foundation.org

Current and future treatments of hidradenitis suppurativa

To obtain credit, you should first read the journal article. After reading the article, you should be able to answer the following, related, multiple-choice questions. To complete the questions and earn continuing medical education (CME) credit, please go to http://www.medscapecme.com/journal/expertderm. Credit cannot be obtained for tests completed on paper, although you may use the worksheet below to keep a record of your answers. You must be a registered user on Medscape.com. If you are not registered on Medscape.com, please click on the New Users: Free Registration link on the left hand side of the website to register. Only one answer is correct for each question. Once you successfully answer all post-test questions you will be able to view and/or print your certificate. For questions regarding the content of this activity, contact the accredited provider, [email protected]. For technical assistance, contact [email protected]. American Medical Association’s Physician’s Recognition Award (AMA PRA) credits are accepted in the US as evidence of participation in CME activities. For further information on this award, please refer to http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/2922.html. The AMA has determined that physicians not licensed in the US who participate in this CME activity are eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Through agreements that the AMA has made with agencies in some countries, AMA PRA credit is acceptable as evidence of participation in CME activities. If you are not licensed in the US and want to obtain an AMA PRA CME credit, please complete the questions online, print the certificate and present it to your national medical association.

Activity Evaluation: Where 1 is strongly disagree and 5 is strongly agree

A 32-year-old woman presents with a 4-month history of recurrent abscesses in her axillae and groin. Her medical history is significant only for obesity. Her only medication is oral contraceptive pills. She smokes a half-pack of cigarettes per day and drinks an average of 2 alcoholic beverages per day.

Which of the following statements about the potential diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) in this patient is most accurate?

□ A HS is unlikely because it occurs in less than 1 in 10,000 adults

□ B HS is unlikely because it usually begins on the stomach and back

□ C Overweight and obesity are associated with a higher risk for HS

□ D Smoking appears to be protective against HS

2. You diagnose this patient with HS, which appears mild to moderate (Hurley stage I) at this time. What would be the most prudent therapy right now?

□ A Prednisone

□ B Methotrexate

□ C Topical clindamycin

□ D Photodynamic therapy

3. The patient worsens despite your initial therapy. What would be the most reasonable treatment choice at this time?

□ A Infliximab

□ B Radiation therapy

□ C Hydroxychloroquine

□ D Isotretinoin

4. The patient continues to worsen, and you are considering surgical treatment for her HS. Which of the following statements about surgical treatment for HS is most accurate

□ A Wider excision yields worse results

□ B Healing by secondary intention yields worse results

□ C Laser therapy should be reserved for severe disease

□ D Laser therapy is not associated with severe side effects