Enuresis is a common medical condition that is often underappreciated by the public and medical community. Enuresis affects millions of children worldwide, and the ramifications resulting from untreated enuresis include low self-esteem, disruption in the family and an increased economic burden with regards to increased family household work. For such a common condition, it is interesting that little research into the treatment of enuresis has been conducted and there continues to be little understanding regarding the etiology for enuresis.

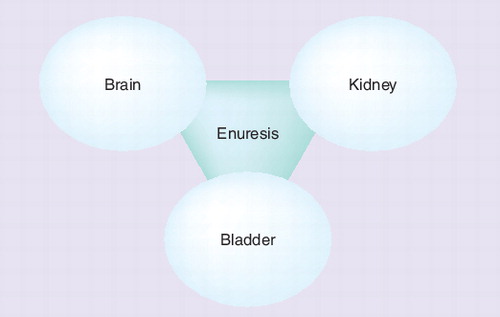

One of the limiting issues in understanding enuresis is its multifactorial nature. It is clear that there are three physiologic components responsible for enuresis, includng the brain, the kidney and the bladder . Enuresis results when disruption of one of these three different organ systems occurs. Poor sleep arousal is characteristic of the lack of CNS modulation on bladder storage that occurs in many children with enuresis Citation[1,2]. In other children, the primary pathophysiology is renal polyuria secondary to insufficient nocturnal arginine vasopressin secretion from the posterior pituitary gland Citation[3,4]. Finally, bladder overactivity is seen in another subset of children with enuresis and is usually typified by daytime, as well as night-time, bladder emptying issues Citation[5,6].

The disruption of the brain, kidney or bladder is felt to be a maturational delay and is supported by the observation that there is a higher incidence of enuresis in young children that resolves over time. For example, 15% of 5-year-olds, 5% of 10-year-olds and 1% of 15-year-olds have enuresis Citation[7–9]. There is an approximately 15% resolution rate in enuresis per year. Given the self-limiting nature of enuresis, one treatment option is to observe and allow the natural history to follow its natural course. Certainly this is a viable option if the child and the family are not troubled by the enuresis. Enuresis usually becomes an issue when the child is of school age and begins to socialize with sleepovers and starts attending summer camps. When families present for treatment, our group focuses on identifying the primary organ system that seems to be the main cause for enuresis. A detailed bladder and bowel elimination history is mandatory in the work-up before initiating therapy. Likewise, gaining insight into the sleep pattern is important in counseling families with regard to treatment options.

Endocrine-mediated therapy targets enuretics that exhibit nocturnal polyuria. Soaked bed sheets, diapers or pull-ups typify nocturnal polyuria. Avoiding diary documenting voided volumes, as well as overnight urine production, will give insight into polyuria. The International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS) defines nocturnal polyuria as nocturnal urine output exceeding 130% of the expected bladder capacity (EBC) for a child of a given age Citation[10]. The nocturnal urine production is calculated by weighing any wet pads or pull-ups, as well as the first morning void. The EBC is estimated in milliliters using the formula [30 + (age in years × 30)] and is applicable until age 12 years when the EBC levels off at 390 ml Citation[11].

When nocturnal polyuria is present, desmopressin acetate is the mainstay of endocrine-mediated treatment for enuresis. The development of desmopressin acetate as a therapy for enuresis is based on the landmark findings of inadequate circadian secretion pattern of arginine vasopressin in children with enuresis Citation[3,4]. In these studies, children with nocturnal polyuria had deficient production of arginine vasopressin during the night. One of the treatment challenges in the management of enuresis is predicting which patients will respond to desmopressin. EBC has been demonstrated to be a reliable predictor of response to desmopressin; children with larger capacities are more likely to exhibit a successful response Citation[12–14].

Owing to the correlation of EBC with desmopressin response, our group has combined desmopressin with anticholinergic therapy in children who fail or partially respond to desmopressin alone. The rationale is based upon potentially increasing the functional bladder capacity with anticholinergic therapy, thereby increasing the response to desmopressin. Intuitively, this therapy seems reasonable in that desmopressin and the anticholinergic are working via two different mechanisms that would seem additive in preventing nocturnal enuresis (e.g., desmopressin decreases urine production and the anticholinergic improves bladder capacity and storage).

Although there have been reports of combination therapy (desmopressin plus anticholinergic), this method of treatment has been reported primarily in children with nocturnal enuresis and lower urinary tract symptoms or overactive bladder Citation[15]. There are only a few studies examining combination therapy in children with desmopressin-resistant monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis in the literature Citation[16–19]. Until recently, no randomized, placebo-controlled trial had been performed, and previous reports utilized short-acting anticholinergics. Our group addressed these issues by examining the efficacy of combination therapy using desmopressin with a sustained-release anticholinergic in a placebo-controlled trial for enuretic children who previously failed to respond to desmopressin single therapy Citation[20]. We found that, after 1 month of treatment, there was a significant reduction in the mean number of wet nights in the combination therapy group compared with placebo. Additionally, using a generalized estimating equation approach, there was a significant decrease in the risk of a wet episode by 66% (odds ratio: 0.33; 95% CI: 0.12–0.98) compared with the placebo group. These results provide validation for using combination therapy as a treatment strategy for children with primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis who are refractory to desmopressin.

It is important to note that our study did not attempt to identify a mechanism that would predict a response to combination therapy in desmopressin nonresponders. Recent research has identified several potential explanations for refractory response to desmopressin despite nocturnal polyuria. These include patients with increased sodium Citation[21,22] and osmotic urinary excretion Citation[23,24], hypercalciuria Citation[25,26] and excess prostaglandin production Citation[21]. Altered circadian rhythm of glomerular filtration and tubular functions has been reported Citation[27], and it is postulated that altered dietary habits in children, such as increased sodium and protein intake, may be responsible for elevated osmotic secretion that results in desmopressin-resistant nocturnal polyuria Citation[24]. Finally, it has been suggested that failure of desmopressin to control nocturnal urine output may be an indication of vasopressin-independent pathways being responsible for the excess urine output at night. Abnormal diurnal rhythms of angiotensin and aldosterone have been hypothesized as alternative mechanisms Citation[28]. Studies are conflicting and several reports have found no evidence of altered secretion of atrial natriuretic peptide, renin or aldosterone Citation[29]. These holes in our understanding of desmopressin-resistant enuresis still require further study. Subsequently, the future of enuresis research is ripe for further investigation.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Yeung CK, Diao M, Sreedhar B. Cortical arousal in children with severe enuresis. N. Engl. J. Med.358(22), 2414–2415 (2008).

- Neveus T. Enuretic sleep: deep, disturbed or just wet? Pediatr. Nephrol.23(8), 1201–1202 (2008).

- Rittig S, Knudsen UB, Norgaard JP, Pedersen EB, Djurhuus JC. Abnormal diurnal rhythm of plasma vasopressin and urinary output in patients with enuresis. Am. J. Physiol.256(4 Pt 2), F664–F671 (1989).

- Norgaard JP, Pedersen EB, Djurhuus JC. Diurnal anti-diuretic-hormone levels in enuretics. J. Urol.134(5), 1029–1031 (1985).

- Yeung CK, Sit FK, To LK et al. Reduction in nocturnal functional bladder capacity is a common factor in the pathogenesis of refractory nocturnal enuresis. BJU Int.90(3), 302–307 (2002).

- Yeung CK, Chiu HN, Sit FK. Bladder dysfunction in children with refractory monosymptomatic primary nocturnal enuresis. J. Urol.162(3 Pt 2), 1049–1054; discussion 1054–1045 (1999).

- Hellstrom AL, Hanson E, Hansson S, Hjalmas K, Jodal U. Micturition habits and incontinence in 7-year-old Swedish school entrants. Eur. J. Pediatr.149(6), 434–437 (1990).

- Forsythe WI, Redmond A. Enuresis and spontaneous cure rate. Study of 1129 enuretis. Arch. Dis. Child.49(4), 259–263 (1974).

- Beer E. Chronic retention of urine in children. JAMA65, 1709–1713 (1915).

- Neveus T, von Gontard A, Hoebeke P et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: report from the Standardisation Committee of the International Children’s Continence Society. J. Urol.176(1), 314–324 (2006).

- Hjalmas K, Arnold T, Bower W et al. Nocturnal enuresis: an international evidence based management strategy. J. Urol.171(6 Pt 2), 2545–2561 (2004).

- Eller DA, Austin PF, Tanguay S, Homsy YL. Daytime functional bladder capacity as a predictor of response to desmopressin in monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. Eur. Urol.33(Suppl. 3), 25–29 (1998).

- Rushton HG, Belman AB, Zaontz MR, Skoog SJ, Sihelnik S. The influence of small functional bladder capacity and other predictors on the response to desmopressin in the management of monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. J. Urol.156(2 Pt 2), 651–655 (1996).

- Kirk J, Rasmussen PV, Rittig S, Djurhuus JC. Micturition habits and bladder capacity in normal children and in patients with desmopressin-resistant enuresis. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. Suppl.173, 49–50 (1995).

- Caione P, Arena F, Biraghi M et al. Nocturnal enuresis and daytime wetting: a multicentric trial with oxybutynin and desmopressin. Eur. Urol.31(4), 459–463 (1997).

- Radvanska E, Kovacs L, Rittig S. The role of bladder capacity in antidiuretic and anticholinergic treatment for nocturnal enuresis. J. Urol.176(2), 764–768 (2006).

- Neveus T. Oxybutynin, desmopressin and enuresis. J. Urol.166(6), 2459–2462 (2001).

- Neveus T, Lackgren G, Tuvemo T, Olsson U, Stenberg A. Desmopressin resistant enuresis: pathogenetic and therapeutic considerations. J. Urol.162(6), 2136–2140 (1999).

- Cendron M, Klauber G. Combination therapy in the treatment of persistent nocturnal enuresis. Br. J. Urol.81(Suppl. 3), 26–28 (1998).

- Austin PF, Ferguson G, Yan Y, Campigotto MJ, Royer ME, Coplen DE. Combination therapy with desmopressin and an anticholinergic medication for nonresponders to desmopressin for monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics122(5), 1027–1032 (2008).

- Kamperis K, Hagstroem S, Rittig S, Djurhuus JC. Urinary calcium excretion in healthy children and children with primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. J. Urol.176(2), 770–773 (2006).

- Aceto G, Penza R, Delvecchio M, Chiozza ML, Cimador M, Caione P. Sodium fraction excretion rate in nocturnal enuresis correlates with nocturnal polyuria and osmolality. J. Urol.171(6 Pt 2), 2567–2570 (2004).

- Dehoorne JL, Walle CV, Vansintjan P et al. Characteristics of a tertiary center enuresis population, with special emphasis on the relation among nocturnal diuresis, functional bladder capacity and desmopressin response. J. Urol.177(3), 1130–1137 (2007).

- Dehoorne JL, Raes AM, van Laecke E, Hoebeke P, Vande Walle JG. Desmopressin resistant nocturnal polyuria secondary to increased nocturnal osmotic excretion. J. Urol.176(2), 749–753 (2006).

- Raes A, Dehoorne J, Van Laecke E et al. Partial response to intranasal desmopressin in children with monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis is related to persistent nocturnal polyuria on wet nights. J. Urol.178(3 Pt 1), 1048–1051 (2007).

- Aceto G, Penza R, Coccioli MS et al. Enuresis subtypes based on nocturnal hypercalciuria: a multicenter study. J. Urol.170(4 Pt 2), 1670–1673 (2003).

- De Guchtenaere A, Raes A, Vande Walle C et al. Evidence of partial anti-enuretic response related to poor pharmacodynamic effects of desmopressin nasal spray. J. Urol.181(1), 302–309 (2009).

- Rittig S, Matthiesen TB, Pedersen EB, Djurhuus JC. Sodium regulating hormones in enuresis. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. Suppl.202, 45–46 (1999).

- Kamperis K, Rittig S, Radvanska E, Jorgensen KA, Djurhuus JC. The effect of desmopressin on renal water and solute handling in desmopressin resistant monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. J. Urol.180(2), 707–713 (2008).