Abstract

Intestinal hematoma, once considered a rare complication of anticoagulation, has recently been increasingly reported. Spontaneous small bowel hematomas most commonly involve the jejunum, followed by the ileum and duodenum. They occur in patients who receive excessive anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists or who have additional risk factors for bleeding. Diagnosis can be readily identified with sonography and confirmed with computed tomography. Early diagnosis is crucial as most patients can be treated successfully without surgery. Conservative treatment is recommended for intramural intestinal hematomas, when other associated complications needing laparotomy have been excluded.

Medscape: Continuing Medical Education Online

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Medscape, LLC and Expert Reviews Ltd. Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 70% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at www.medscape.org/journal/expertneurothera; (4) view/print certificate.

Release date: 12 October 2012; Expiration date: 12 October 2013

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants will be able to:

• Distinguish common anatomic locations of spontaneous intestinal hematomas

• Analyze the clinical presentation of spontaneous intestinal hematomas

• Evaluate imaging modalities for spontaneous intestinal hematomas

• Assess appropriate management of spontaneous intestinal hematomas

Financial & competing interests disclosure

EDITOR

Elisa Manzotti

Publisher, Future Science Group, London, UK

Disclosure: Elisa Manzotti has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

CME Author

Charles P Vega, MD

Health Sciences Clinical Professor, Residency Director, Department of Family Medicine, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA

Disclosure: Charles P. Vega MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Authors and Credentials

Ahmed Abdel Samie, MD

Department of Gastroenterology, Pforzheim Hospital, Pforzheim, Germany

Disclosure: Ahmed Abdel Samie, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Lorenz Theilmann, MD

Department of Gastroenterology, Pforzheim Hospital, Pforzheim, Germany

Disclosure: Lorenz Theilmann, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Vitamin K antagonists (VKA; phenprocoumon/warfarin/acenocoumarol) are used extensively for therapeutic and prophylactic purposes. The most important complication of anticoagulant therapy is bleeding. However, bleeding complications of over anticoagulation may present in unusual ways.

Intramural small bowel hematoma has been recognized for many years as a complication of blunt trauma, especially in children. In contrast to traumatic small bowel hematoma, which mainly affects the duodenum and tends to involve a short intestinal segment, spontaneous small bowel hematoma is more extensive and most commonly involves the jejunum, followed by the ileum and duodenum Citation[1]. The most common cause of this condition is over-anticoagulation under VKA.

This rare clinical entity was initially reported in 1838 by McLauchlan at the autopsy of a 49-year-old man who died of dehydration and duodenal obstruction resulting from a false aneurysmal tumor occluding the duodenum Citation[2]. Approximately 70 years later, Sutherland described a case of a nontraumatic intramural small bowel hematoma in a child with Henoch–Schönlein purpura presenting with intussusception Citation[3]. Hematoma of the esophagus, colon and rectum has also been reported Citation[4–6]. Nontraumatic spontaneous intramural small bowel hematoma, once considered a rare complication of anticoagulation, is being reported with increasing frequency Citation[7–9]. The incidence of this clinical entity is predicted to increase further, as a result of wide use of long-term anticoagulation and the development of new, very effective, direct oral anticoagulants in an aging population.

Epidemiology

Spontaneous intestinal intramural hematoma is a rare complication under anticoagulant therapy. An incidence of one in 2500 patients receiving warfarin was reported Citation[10]. The incidence is higher in males and the average age at presentation is 58 years Citation[9]. Because of the rarity of spontaneous intramural small bowel hematoma, there are only case reports dealing with this clinical entity in the literature. The largest series included 13 patients, of whom eight received oral anticoagulation Citation[7].

Etiology

Intramural small bowel hematoma may arise spontaneously or traumatic. Blunt abdominal trauma is by far the most common etiologic factor for duodenal hematoma and is responsible for approximately 90% of cases. The relatively fixed retroperitoneal position of the duodenum and its close anterior relationship to the lumbar spine renders it susceptible to blunt trauma of a crushing type and accounts for the higher incidence of duodenal involvement in this situation Citation[1]. This condition mainly involves children, and the trauma is frequently insignificant that it is forgotten by the patient. The weak abdominal muscles and the high costal margin contribute to the susceptibility of children to intramural duodenal hematoma Citation[11]. Over-anticoagulation with VKA is the most common cause of spontaneous intramural small bowel hematoma. Although spontaneous intramural small bowel hematoma may be expected to occur with over-anticoagulation by heparin, the authors found only one case report describing this complication in a child who received therapeutic doses of low-molecular-weight heparin due to deep venous thrombosis Citation[12].

Antiplatelet therapy is widely used for therapeutic and prophylactic purposes. Despite the increased usage of these drugs and the necessity of dual antiplatelet therapy for least 1 month and at least 6 months after coronary intervention with implantation of bare metal or drug eluting stents, to the authors’ knowledge, there are no case reports describing the association between small bowel hematoma and the usage of antiplatelet medication.

In addition to excessive anticoagulation, this condition has also been described as a complication of bleeding disorders, malignancies and vasculitis Citation[7]. Endoscopic biopsies and injection therapy have been reported as a further cause of intramural hematoma. However, iatrogenic intramural duodenal hematoma represents a very rare complication of endoscopic procedures and occurs mainly in patients with coagulation or hematological disorders Citation[13]. The relatively fixed retroperitoneal position of the duodenum and its rich submucosal blood supply may play a role in the development of this complication following biopsies or injection therapy, which can cause shearing of the mucosa from the fixed duodenal submucosa resulting in submucosal hemorrhage in predisposed individuals with bleeding disorders Citation[13].

An association between acute and chronic pancreatitis and intramural intestinal hematoma was also described in the literature, although the exact pathomechanism behind this linkage is not completely understood. In this setting, vascular erosions by pancreatic enzymes may play a causative role for the development of submucosal hemorrhage Citation[14,15]. Spontaneous intramural intestinal hematoma has also been reported as a complication of pancreatic carcinoma Citation[16]. The small bowel is affected in up to 85% of the cases of spontaneous intramural gastrointestinal tract hematoma caused by excessive anticoagulation, with the jejunum being the most affected region. Nevertheless, it remains unclear why the jejunum is the site of predilection for spontaneous hematoma.

Bleeding originates in the submucosa from small vessels that produce slow bleeding. Some authors speculate that the progression of the symptoms is due to an intramural osmotic gradient caused by the hematoma, leading to its expansion in the intestinal wall with lumen occlusion Citation[17]. Although intramural hematoma is mainly localized in the small intestine, upper and lower GI tract affection has been reported. Small bowel hematoma can extend into the colon; however, isolated cases are very rare. It has been hypothesized that the taenia coli may play a protective role against the initiation or expansion of the hemorrhage Citation[8]. This condition may be associated with excessive anticoagulation with VKA as shown by Celik et al. Citation[18].

The esophagus represents another rare location for intramural hematoma and nearly all cases present with chest pain. Causes include instrumentation, injection therapy and ingestion of foreign bodies. An association with achalasia has been also described in the literature Citation[19]. Rectal hematoma is, in most cases, traumatic resulting from insertion of foreign bodies. Furthermore, iatrogenic hematomas following injection therapy or stapled hemorrhoidopexy were reported Citation[20].

Clinical presentation

The spectrum of presentation is wide and can vary from mild, vague abdominal pain to intestinal obstruction and acute abdomen pain. Nausea and vomiting are found in half of the cases and are related to high intestinal obstruction involving the duodenum and proximal jejunum. Patients may also present with gastrointestinal hemorrhage as a result of ruptured hematoma Citation[21]. However, obvious bleeding is present in less than half of the cases and cannot be relied upon as a diagnostic criterion Citation[22].

Signs of peritoneal irritation may be present in some cases and usually indicate the development of complications, such as necrosis, perforation or hemoperitoneum. The average time from the appearance of symptoms until medical attendance varies between 2 and 4 days Citation[9]. The duration of usage of VKA varies widely from 1 to 132 months. In one case report, however, this complication occurred after only 8 days of warfarin usage Citation[23].

In the largest reported series of spontaneous small bowel hematoma including 13 patients, the mean age of presentation was 64 years. Small bowel obstruction was present in 85% of the patients, and the jejunum was the most common site of the hematoma, followed by the ileum and duodenum. All patients presented with abdominal pain. The mean international normalized rate at presentation was 12 Citation[7].

Imaging findings

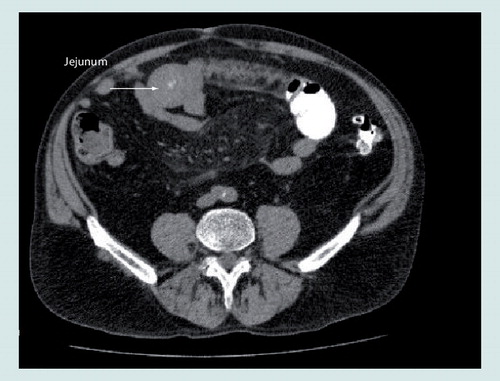

Computed tomography (CT) is the key for the diagnosis of this condition. Some authors have suggested that a non-contrast CT scan should be preformed prior to oral and intravenous contrast application, as contrast enhanced scans alone may mask the presence of intramural hemorrhage Citation[9]. Characteristic findings on CT include circumferential wall thickening, intramural hyperdensity, luminal narrowing and intestinal obstruction Citation[7,24].

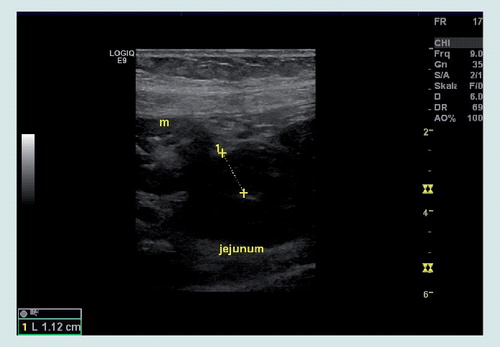

The sonographic appearance of acute intramural small bowel hematoma consists of a thickened intestinal wall mainly involving the submucosal layer . However, this abnormality is not specific for intestinal tract hematomas and can be seen in a wide spectrum of disorders Citation[1,25]. The involved bowel appears longer in spontaneous hematomas than in traumatic hematomas with the average length of the affected intestinal segment measuring 23 cm Citation[7,8].

The combination of CT and ultrasound can show the exact pathology in all patients, as demonstrated by some authors Citation[26]. MRI characteristics of duodenal hematoma include a high signal intensity well-defined concentric ring (ring sign). The unique MRI tissue characteristics (ring with short T1 and long T2 relaxation times) are attributable to the paramagnetic properties of iron species within the hematoma Citation[27].

However, no data are available on the MRI imaging characteristics of small bowel hematomas other than those that occur in the duodenum. With the help of pull and push enteroscopy, deep small bowel lesions can be visualized Citation[28]. However, the role of endoscopy in the diagnosis of intramural hematoma is not well established, as almost all cases are diagnosed ‘noninvasively’ with CT and ultrasound scans. However, endoscopy may play a therapeutic role as shown by Kwon et al., who have successfully treated a duodenal hematoma with a needle knife incision relieving obstructive symptoms Citation[29].

Therapy

Due to the rarity of this entity, there are no studies that contain sufficient evidence to standardize treatment. The first step in the treatment of acute intramural small bowel hematoma is discontinuation of the anticoagulant medication and correction of coagulation parameters with vitamin K. Treatment also includes fluid replacement and nasogastric tube suction.

Conservative treatment usually leads to improvement of symptoms within 4–6 days. Complete resolution usually occurs within 2 months after the onset, as the hemorrhagic bowel is not necrotic, and complete restitution occurs in almost all cases under conservative measures Citation[22,30,31]. It appears safe to resume anticoagulant therapy in patients after resolution of the hematoma as long as it is administered within the therapeutic range. Neither recurrence of intestinal obstruction or hematoma nor long-term sequelae were observed in this group Citation[10].

Laparotomy is not indicated in uncomplicated intramural hematoma of the small bowel. Surgical exploration is reserved for cases with diagnosis doubt or late complications, that include intra-abdominal hemorrhage, suspected ischemia, perforation, peritonitis and intestinal obstruction not responding to conservative measures Citation[9,10,22,31].

Expert commentary

The recognition of intramural hematoma from anticoagulant drugs as a clinical entity is vitally important in prevention, diagnosis and treatment of this condition. A high index of suspicion on this rare complication of over-anticoagulation is required for making accurate diagnosis. Intramural hematoma of the small bowel should be investigated in any patient with abdominal pain who is receiving anticoagulant therapy, especially if the international normalized rate is excessively prolonged. It is extremely important to recognize this condition in order to avoid an unnecessary operation since the outcome is usually excellent after conservative treatment.

Five-year view

Nontraumatic spontaneous intramural small bowel hematoma, once considered a rare complication of anticoagulation, is being reported with increasing frequency. The combination of CT and ultrasound can show the exact pathology in almost all patients. The role of endoscopy in the diagnosis of intramural hematoma is not well established, as almost all cases are diagnosed ‘non invasively’. However, endoscopy may play a therapeutic role (e.g., needle knife incision of the hematoma). The incidence of this clinical entity is predicted to further increase, as a result of wide use of long-term anticoagulation in an aging population.

Table 1. Summary of the latest published case reports on spontaneous intramural intestinal hematoma due to anticoagulant therapy.

Key issues

• Intestinal hematoma, once considered a rare complication of anticoagulation, has recently been increasingly reported.

• Blunt abdominal trauma is by far the most common etiologic factor for duodenal hematoma.

• Over-anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists is the most common cause of spontaneous intramural small bowel hematoma.

• The spectrum of presentation is wide and can vary from mild, vague abdominal pain to intestinal obstruction and acute abdominal pain.

• Computed tomography is the key for diagnosis of this condition.

• The combination of computed tomography and ultrasound can show the exact pathology in nearly all patients.

• The first step in the treatment of acute intramural small bowel hematoma is discontinuation of the anticoagulant medication and correction of coagulation parameters with vitamin K.

• It is extremely important to recognize this condition in order to avoid an unnecessary operation since the outcome is usually excellent after conservative treatment.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Altikaya N, Parlakgümüs A, Demir S, Alkan Ö, Yildirim T. Small bowel obstruction caused by intramural hematoma secondary to warfarin therapy: a report of two cases. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 22(2), 199–202 (2011).

- McLauchlan J. Fatal false aneurysmal tumour occupying nearly the whole of the duodenum. Lancet 2, 203–205 (1883).

- Sutherland GA. Intussusception and Henoch’s purpura. Br. J. Dis. Child. 1, 23–28 (1904).

- Liu Y, Yang S, Tong Q. Spontaneous intramural hematoma of colon. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10(4), e38 (2011).

- Jarry J, Biscay D, Lepront D, Rullier A, Midy D. Spontaneous intramural haematoma of the sigmoid colon causing acute intestinal obstruction in a haemophiliac: report of a case. Haemophilia 14(2), 383–384 (2008).

- Shimodaira M, Nakajima Y, Akiyama T, Koyama S. Spontaneous intramural haematoma of the oesophagus. Intern. Med. J. 41(7), 577–578 (2011).

- Abbas MA, Collins JM, Olden KW. Spontaneous intramural small-bowel hematoma: imaging findings and outcome. AJR. Am. J. Roentgenol. 179(6), 1389–1394 (2002).

- Abbas MA, Collins JM, Olden KW, Kelly KA. Spontaneous intramural small-bowel hematoma: clinical presentation and long-term outcome. Arch. Surg. 137(3), 306–310 (2002).

- Sorbello MP, Utiyama EM, Parreira JG, Birolini D, Rasslan S. Spontaneous intramural small bowel hematoma induced by anticoagulant therapy: review and case report. Clinics (Sao. Paulo) 62(6), 785–790 (2007).

- Jimenez J. Abdominal pain in a patient using warfarin. Postgrad. Med. J. 75(890), 747–748 (1999).

- Jones WR, Hardin WJ, Davis JT, Hardy JD. Intramural hematoma of the duodenum: a review of the literature and case report. Ann. Surg. 173(4), 534–544 (1971).

- Shaw PH, Ranganathan S, Gaines B. A spontaneous intramural hematoma of the bowel presenting as obstruction in a child receiving low-molecular-weight heparin. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 27(10), 558–560 (2005).

- Sugai K, Kajiwara E, Mochizuki Y et al. Intramural duodenal hematoma after endoscopic therapy for a bleeding duodenal ulcer in a patient with liver cirrhosis. Intern. Med. 44(9), 954–957 (2005).

- Dubois J, Guy F, Porcheron J. A pancreatic-induced intramural duodenal hematoma: a case report and literature review. Hepatogastroenterology 50(53), 1689–1692 (2003).

- Ma JK, Ng KK, Poon RT, Fan ST. Pancreatic-induced intramural duodenal haematoma. Asian J. Surg. 31(2), 83–86 (2008).

- Chou AL, Tseng KC, Hsieh YH, Feng WF, Tseng CA. Intramural duodenal hematoma as a complication of pancreatic cancer. Endoscopy 39, 107–108 (2007).

- Judd DR, Taybi H, King H. Intramural hematoma of the small bowel; a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Arch. Surg. 89, 527–535 (1964).

- Celik A, Ozkan N, Ersoy OF, Acu B, Kayaoglu HA. Clinical challenges and images in GI. Intramural intestinal hematoma. Gastroenterology 134(2), 387, 647 (2008).

- Chu YY, Sung KF, Ng SC, Cheng HT, Chiu CT. Achalasia combined with esophageal intramural hematoma: case report and literature review. World J. Gastroenterol. 16(42), 5391–5394 (2010).

- Augustin G, Smud D, Kinda E et al. Intra-abdominal bleeding from a seromuscular tear of an ascending rectosigmoid intramural hematoma after stapled hemorrhoidopexy. Can. J. Surg. 52(1), E14–E15 (2009).

- Veldt BJ, Haringsma J, Florijn KW, Kuipers EJ. Coumarin-induced intramural hematoma of the duodenum: case report and review of the literature. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 46(3), 376–379 (2011).

- Askey JM. Small bowel obstruction due to intramural hematoma during anticoagulant therapy, a non-surgical condition. Calif. Med. 104(6), 449–453 (1966).

- Chaiteerakij R, Treeprasertsuk S, Mahachai V, Kullavanijaya P. Anticoagulant-induced intramural intestinal hematoma: report of three cases and literature review. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 91(8), 1285–1290 (2008).

- Cheng J, Vemula N, Gendler S. Small bowel obstruction caused by intramural hemorrhage secondary to anticoagulant therapy. Acta Gastroenterol. Belg. 71(3), 342–344 (2008).

- Rauh P, Uhle C, Ensberg D et al. Sonographic characteristics of intramural bowel hematoma. J. Clin. Ultrasound 36(6), 367–368 (2008).

- Polat C, Dervisoglu A, Guven H et al. Anticoagulant-induced intramural intestinal hematoma. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 21(3), 208–211 (2003).

- Abdel Samie A, Sun R, Theilmann L. A rare cause of obstructive jaundice. Gastroenterology 137(1), 40 (2009).

- Shinozaki S, Yamamoto H, Kita H et al. Direct observation with double-balloon enteroscopy of an intestinal intramural hematoma resulting in anticoagulant ileus. Dig. Dis. Sci. 49(6), 902–905 (2004).

- Kwon CI, Ko KH, Kim HY et al. Bowel obstruction caused by an intramural duodenal hematoma: a case report of endoscopic incision and drainage. J. Korean Med. Sci. 24(1), 179–183 (2009).

- Carkman S, Ozben V, Saribeyoglu K et al. Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the small intestine. Ulus. Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 16(2), 165–169 (2010).

- Ashley S. Spontaneous mesenteric haematoma and small bowel infarction complicating oral anticoagulant therapy. J. R. Soc. Med. 83(2), 116 (1990).

- Reyes Garay H, Tagle Arróspide M. [Spontaneous intramural hematoma of the small bowel due to use of oral anticoagulants: case report and review of the literature]. Rev. Gastroenterol. Peru. 30(2), 158–162 (2010).

- Birla RP, Mahawar KK, Saw EY, Tabaqchali MA, Woolfall P. Spontaneous intramural jejunal haematoma: a case report. Cases J. 1(1), 389 (2008).

- Hou SW, Chen CC, Chen KC, Ko SY, Wong CS, Chong CF. Sonographic diagnosis of spontaneous intramural small bowel hematoma in a case of warfarin overdose. J. Clin. Ultrasound 36(6), 374–376 (2008).

Detection and management of spontaneous intramural small bowel hematoma secondary to anticoagulant therapy

To obtain credit, you should first read the journal article. After reading the article, you should be able to answer the following, related, multiple-choice questions. To complete the questions (with a minimum 70% passing score) and earn continuing medical education (CME) credit, please go to www.medscape.org/journal/expertgastrohep. Credit cannot be obtained for tests completed on paper, although you may use the worksheet below to keep a record of your answers. You must be a registered user on Medscape.org. If you are not registered on Medscape.org, please click on the New Users: Free Registration link on the left hand side of the website to register. Only one answer is correct for each question. Once you successfully answer all post-test questions you will be able to view and/or print your certificate. For questions regarding the content of this activity, contact the accredited provider, [email protected]. For technical assistance, contact [email protected]. American Medical Association's Physician's Recognition Award (AMA PRA) credits are accepted in the US as evidence of participation in CME activities. For further information on this award, please refer to http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/category/2922.html. The AMA has determined that physicians not licensed in the US who participate in this CME activity are eligible for AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™. Through agreements that the AMA has made with agencies in some countries, AMA PRA credit may be acceptable as evidence of participation in CME activities. If you are not licensed in the US, please complete the questions online, print the AMA PRA CME credit certificate and present it to your national medical association for review.

Activity Evaluation: Where 1 is strongly disagree and 5 is strongly agree

1. You are seeing a 60-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation. She has a variety of complaints, including bleeding gums, increased bruising, lower extremity edema, and vague abdominal pain. She receives warfarin, and her international normalized ratio (INR) is 6.2.

You consider whether this patient has developed an intestinal hematoma. What is the most common anatomic site for hematoma if this is the case?

□ A Jejunum

□ B Duodenum

□ C Ileum

□ D Proximal colon

2. What should you consider regarding the clinical presentation of spontaneous intestinal hematomas?

□ A They are as common with antiplatelet therapy as they are with warfarin

□ B Nearly all patients have evidence of gross gastrointestinal hemorrhage

□ C Most patients present urgently within hours of the bleeding event

□ D The INR is significantly elevated in all reported cases

3. The patient leaves your clinic but returns the following day with worsening abdominal symptoms. You decide to order diagnostic imaging. Which of the following statements regarding imaging studies for spontaneous intestinal hematomas is most accurate?

□ A Ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice for the diagnosis of spontaneous intestinal hematoma

□ B A thickened intestinal wall on ultrasound is pathognomonic for spontaneous intestinal hematoma

□ C Findings of spontaneous intestinal hematoma on CT include intramural hyperdensity and luminal narrowing

□ D Findings of spontaneous intestinal hematoma on MRI include the lack of a ring sign

4. The diagnosis of intramural hematoma of the small bowel is confirmed. What are the best next steps in the management of this patient?

□ A Exploratory laparoscopy

□ B Exploratory laparotomy

□ C Immediate discontinuation of warfarin with restart of warfarin after resolution of the hematoma

□ D Immediate and permanent discontinuation of warfarin