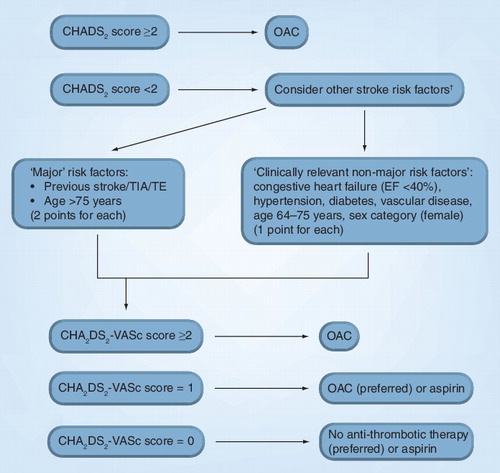

†Other stroke risk factors can be classified as ‘major’ risk factors and ‘clinically relevant non-major’ risk factors, that can also be expressed as the CHA2DS2-VASc score (see ).

CHADS2: Congestive heart failure, hypertension, age 75 years or older, diabetes, stroke (doubled); CHA2DS2-VASc: Congestive heart failure/LV dysfunction, hypertension, aged ≥75 years (doubled), diabetes mellitus, prior stroke/TIA/TE (doubled)–vascular disease, aged 65–74 years, sex category; EF: Ejection fraction; OAC: Oral anticoagulation therapy; TE: Thromboembolism; TIA: Transient ischemic attack.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) remains the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia in clinical practice. Hemodynamic impairment and thromboembolic events related to AF result in significant morbidity, mortality, impairment of quality of life and health-service costs. The number of patients with AF is likely to increase 2.5-fold during the next 50 years, reflecting the ageing population Citation[1]. To face the increasing challenge of optimal stroke prevention and rhythm management in patients with AF, guidelines require regular updating to reflect new concepts and advances in management. A lot has changed since the last 2006 joint American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines, and recently, the ESC has updated its guidelines for the management of AF with more emphasis on European clinical practice Citation[2].

Thromboprophylaxis is the cornerstone of AF management Citation[3,4]. Extensive evidence supporting the high clinical efficacy of oral anticoagulation Citation[5] and insufficient adherence to previous thromboprophylaxis guidelines in ‘real-world’ AF at the same time Citation[6] prompted authors of the ESC guidelines to recommend decision-making regarding anti-thrombotic therapy in AF patients using an approach based on the presence (or absence) of risk factors for thromboembolism and bleeding, ability to safely sustain adjusted chronic anticoagulation and patient preferences. This objective risk factor-based approach is far more logical than the more subjective (and artificial) ‘low’, ‘moderate’ and ‘high’ risk categorization, given the poor predictive value of these categories, as well as recognizing the cumulative nature of stroke risk factors.

Given that the CHADS2 (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years, diabetes, stroke [doubled]) score is simple and in common clinical use, the ESC guidelines recommend the CHADS2 score as an initial, rapid and easy-to-remember means of assessing stroke risk. In patients with a CHADS2 score of 2 or more, chronic oral anticoagulation, for example, with a vitamin K antagonist (VKA) is recommended in a dose-adjusted approach to achieve an international normalized ratio (INR) target of 2.5 (2.0–3.0), unless contraindicated. Other new oral anticoagulants may well be alternatives to the VKAs. Indeed, oral anticoagulation has been proven to improve outcomes in AF patients in real-world clinical practice Citation[7].

However, the limitations of the CHADS2 score are well recognized Citation[8]. For patients with CHADS2 score 0–1, or where a more detailed stroke risk assessment is required, the ESC guidelines recommend a risk factor-based approach by consideration of additional stroke risk factors or ‘stroke risk modifiers’. The guidelines define ‘major risk factors’ as previous stroke/transient ischemic attack or thromboembolism and ‘age 75 years or older’, as well as ‘clinically relevant non-major risk factors’ such as congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, age 65–74 years, vascular disease and female gender. Thus, extra weighting is given to ‘age 75 years or older’ as a single risk factor, and other risk factors not included in the CHADS2 score (e.g., age 65–74 years, female gender and vascular disease) should be considered. These additional clinically relevant non-major risk factors can be expressed as the CHA2DS2-VASc (congestive heart failure/LV dysfunction, hypertension, aged ≥75 years [doubled], diabetes mellitus, prior stroke/transient ischemic attack/thromboembolism [doubled]–vascular disease, aged 65–74 years, sex category) score Citation[9–12].

Based on the CHA2DS2-VASc score, age 75 years or older is considered as a major risk factor alongside previous stroke/transient ischemic attack/thromboembolism, and oral anticoagulation is recommended – this is in contrast to the previous 2006 guidelines, which allowed anti-thrombotic therapy with either a VKA or aspirin in patients age 75 years or older with no other associated risk factors and, thus, many of these patients were given aspirin Citation[13,14].

In subjects with one major or two or more clinically relevant non-major risk factors (i.e., CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥2), oral anticoagulation is clearly merited . For patients with one clinically relevant non-major risk factor (i.e., CHA2DS2-VASc score = 1), thromboprophylaxis with anti-thrombotic therapy is recommended, and oral anticoagulant therapy is preferred over aspirin, especially if patients value stroke prevention over the potential risk of bleeding with anti-thrombotic therapy, given the available evidence Citation[15,16]. In practice, elderly AF patients are less likely to receive therapy with oral anticoagulants, mainly because of concerns about a higher bleeding risk associated with VKAs; however, the relative risk reduction by oral anticoagulants for ischemic stroke persists in the oldest patients with AF, and aspirin may not be any safer. Indeed, the relative benefit of oral anticoagulants versus placebo or antiplatelet agents does not vary by patient age for any outcome (ischemic stroke, serious bleeding and cardiovascular event), whereas the relative efficacy of antiplatelet agents to prevent ischemic stroke decreases as patients get older Citation[17,18], making oral anticoagulation an even more attractive treatment choice for stroke reduction in elderly patients with AF.

An important point is careful maintenance of a therapeutic INR, regardless of patient age. A lower target INR range (1.6–2.5) has previously been proposed for the elderly at increased risk of bleeding; however, an INR less than 2.0 is not associated with a lower rate of intracranial hemorrhage than standard INR targets in the elderly Citation[19] and is not recommended given the increased risk of thromboembolic events at suboptimal INR levels Citation[20]. The time spent in therapeutic range of INR is also crucial both for bleeding and for stroke rate. Recent studies have demonstrated that time in the therapeutic range needs to be at least 58% to derive benefit from oral anticoagulation Citation[21].

Choice of anti-thrombotic strategy must be based upon both thromboembolic and bleeding risk assessment. Many risk factors for anticoagulation-related bleeding are also indications for the use of oral anticoagulants in AF patients Citation[22]. Different bleeding risk stratification schemas have been proposed, but many are not user friendly nor well validated in prospective cohorts of AF patients. To unify assessment of bleeding risk in AF patients, a simple and easily applicable bleeding risk score, HAS-BLED (hypertension, abnormal renal/liver function, stroke, bleeding history or predisposition, labile INR, elderly [e.g., >65 years of age], drugs/alcohol concomitantly), derived from a real-world AF population, has been introduced in the new ESC guidelines Citation[23]. In this schema, 1 point is allocated for the presence of each risk factor, and a HAS-BLED score of 3 or more is indicated as a high risk of bleeding, which means that some caution and regular review of the patients is needed following the initiation of anti-thrombotic therapy, whether with a VKA or aspirin, given that the major bleeding risk with aspirin is similar to that with VKA, especially in elderly individuals Citation[18].

The new ESC guidelines also provide recommendations on the anti-thrombotic strategy following coronary artery stenting for patients with AF requiring oral anticoagulation therapy. Indeed, coronary artery disease is present in 20% or more of the AF population Citation[24]. For now, the addition of aspirin to VKA for stable vascular disease associated with AF is a common scenario, although in patients with stable vascular disease, without acute ischemic events or percutaneous coronary intervention/stent procedures in the preceding year, monotherapy with VKA is at least as effective as aspirin, but addition of aspirin increases bleeding risk significantly Citation[25]. The situation is quite different for AF patients requiring percutaneous coronary intervention with or without stenting. The new ESC guidelines based their recommendations on a systematic review and consensus document from the ESC Working Group on Thrombosis, endorsed by the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions, whereby drug-eluting stents should be avoided and triple therapy (VKA, aspirin and clopidogrel) used in the short term (2–4 weeks, depending on hemorrhagic risk and clinical setting), followed by longer therapy (up to 12 months) with VKA plus a single antiplatelet agent (aspirin or clopidogrel) Citation[2,26].

In the ESC guidelines, the majority of patients with AF should receive oral anticoagulation. In patients with AF for whom VKA therapy is unsuitable or where VKA is declined, the addition of clopidogrel to aspirin has been shown to reduce the risk of major vascular events, especially stroke, but increase the risk of major hemorrhage Citation[27]. Thus, dual antiplatelet therapy may be an alternative to oral anticoagulation in patients for whom there is patient refusal to take VKA or inability to safely sustain adjusted chronic anticoagulation, but not in patients with high bleeding risk. Such an approach has been subject to debate Citation[28,29]. Clearly, the scenario would change with new oral anticoagulants that do not have the disutility or limitations of the VKAs, which include the need for regular monitoring.

In conclusion, improvements in the assessment of thromboembolism and bleeding risks provide practical tools to evaluate individual risk in real-world AF patients, supporting clinicians in their decision regarding anti-thrombotic therapy. This approach, considering stroke and bleeding risk stratification, will also aid in choosing the optimal thromboprophylaxis strategy, especially should the novel oral anticoagulants (e.g., dabigatran with its dose-dependent efficacy/bleeding risk profile) receive regulatory approval for stroke prevention. Of note, individual risk varies over time, thus it must be re-evaluated periodically in all patients with AF.

Table 1. Assessment of stroke (CHA2DS2-VASc) and bleeding risk (HAS-BLED).

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA285, 2370–2375 (2001).

- Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA); endorsed by the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J.31(19), 2369–2429 (2010).

- Rietbrock S, Plumb JM, Gallagher AM, van Staa TP. How effective are dose-adjusted warfarin and aspirin for the prevention of stroke in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation? An analysis of the UK General Practice Research Database. Thromb. Haemost.101, 527–534 (2009).

- Tay KH, Lip GY, Lane DA. Atrial fibrillation and stroke risk prevention in real-life clinical practice. Thromb. Haemost.101, 415–416 (2009).

- Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann. Intern. Med.146, 857–867 (2007).

- Ogilvie IM, Newton N, Welner SA, Cowell W, Lip GY. Underuse of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Am. J. Med.123, 638–645.e4 (2010).

- Go AS, Hylek EM, Chang Y et al. Anticoagulation therapy for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: how well do randomized trials translate into clinical practice? JAMA290(20), 2685–2692 (2003).

- Karthikeyan G, Eikelboom JW. The CHADS2 score for stroke risk stratification in atrial fibrillation – friend or foe? Thromb. Haemost.104, 45–48 (2010).

- Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the Euro Heart Survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest137, 263–272 (2010).

- Lane DA, Lip GY. Female gender is a risk factor for stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation patients. Thromb. Haemost.101, 802–805 (2009).

- Conway DS, Lip GY. Comparison of outcomes of patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease with and without atrial fibrillation (the West Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Project). Am. J. Cardiol.93(11), 1422–1425, A10 (2004).

- Marinigh R, Lip GY, Fiotti N, Giansante C, Lane DA. Age as a risk factor for stroke in atrial fibrillation patients implications for thromboprophylaxis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.56, 827–837 (2010).

- Hylek EM. Contra: ‘Warfarin should be the drug of choice for thromboprophylaxis in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation’. Caveats regarding use of oral anticoagulant therapy among elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Thromb. Haemost.100, 16–17 (2008).

- Mant JW. Pro: ‘Warfarin should be the drug of choice for thromboprophylaxis in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation’. Why warfarin should really be the drug of choice for stroke prevention in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Thromb. Haemost.100, 14–15 (2008).

- Gorin L, Fauchier L, Nonin E et al. Antithrombotic treatment and the risk of death and stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHADS2 score=1. Thromb. Haemost.103, 833–840 (2010).

- Lip GY. Anticoagulation therapy and the risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation at ‘moderate risk’ [CHADS2 score=1]: simplifying stroke risk assessment and thromboprophylaxis in real-life clinical practice. Thromb. Haemost.103, 683–685 (2010).

- van Walraven C, Hart RG, Connolly S et al. Effect of age on stroke prevention therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation: the atrial fibrillation investigators. Stroke40, 1410–1416 (2009).

- Mant J, Hobbs FD, Fletcher K et al.; BAFTA Investigators; Midland Research Practices Network (MIDREC). Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study, BAFTA): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet370, 493–503 (2007).

- Pengo V, Cucchini U, Denas G et al. Lower versus standard intensity oral anticoagulant therapy (OAT) in elderly warfarin-experienced patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Thromb. Haemost.103, 442–449 (2010).

- Singer DE, Chang Y, Fang MC et al. Should patient characteristics influence target anticoagulation intensity for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation?: the ATRIA study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes2, 297–304 (2009).

- Connolly SJ, Pogue J, Eikelboom J et al.; ACTIVE W Investigators. Benefit of oral anticoagulant over antiplatelet therapy in atrial fibrillation depends on the quality of international normalized ratio control achieved by centers and countries as measured by time in therapeutic range. Circulation118, 2029–2037 (2008).

- Hughes M, Lip GY; Guideline Development Group for the NICE national clinical guideline for management of atrial fibrillation in primary and secondary care. Risk factors for anticoagulation-related bleeding complications in patients with atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. QJM100, 599–607 (2007).

- Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess one-year risk of major bleeding in atrial fibrillation patients: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest DOI: 10.1378/chest.10-0134 (2010) (Epub ahead of print).

- Nieuwlaat R, Capucci A, Camm AJ et al.; European Heart Survey Investigators. Atrial fibrillation management: a prospective survey in ESC member countries: the Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Eur. Heart J.26, 2422–2434 (2005).

- Lip GY. Don’t add aspirin for associated stable vascular disease in a patient with atrial fibrillation receiving anticoagulation. Br. Med. J.336, 614–615 (2008).

- Lip GY, Huber K, Andreotti F et al.; European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis. Management of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention/stenting. Thromb. Haemost.103, 13–28 (2010).

- Connolly SJ, Pogue J, Hart RG et al.; ACTIVE Investigators. Effect of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med.360, 2066–2078 (2009).

- Apostolakis S, Shantsila E, Lip GY, Lane DA. Contra: ‘Anti-platelet therapy is an alternative to oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation’. Thromb. Haemost.102, 914–915 (2009).

- Healey JS. Pro: ‘Anti-platelet therapy is an alternative to oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation’. Thromb. Haemost.102, 912–913 (2009).