Abstract

The increasing prevalence of chronic pain with its major societal impact and the escalating use of opioids in managing it, along with their misuse, abuse, associated fatalities and costs, are epidemics in modern medicine. Over the past two decades, multiple lessons have been learned addressing various issues of abuse. Multiple measures have already been incorporated and more are expected to be incorporated in the future, which in turn may curtail the abuse of drugs and reduce healthcare costs, but these measures may also jeopardize access to appropriate pain treatment. This manuscript describes the lessons learned from the misuse, abuse and diversion of opioids, escalating healthcare costs and the means to control this epidemic.

Medscape: Continuing Medical Education Online

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Medscape, LLC and Expert Reviews Ltd. Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 70% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at www.medscape.org/journal/expertneurothera; (4) view/print certificate.

Release date: 29 April 2013; Expiration date: 29 April 2014

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants will be able to:

• Assess the epidemiology of prescription opioid abuse

• Distinguish the health impact of prescription opioid abuse

• Distinguish the economic impact of prescription opioid abuse

• Identify means to reduce the risk of prescription opioid abuse

Financial & competing interests disclosure

EDITOR

Elisa Manzotti

Publisher, Future Science Group, London, UK.

Disclosure: Elisa Manzotti has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

CME AUTHOR

Charles P Vega, MD, Associate Professor and Residency Director, Department of Family Medicine, University of California, Irvine, USA.

Disclosure: CP Vega, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

AUTHORS AND CREDENTIALS

Laxmaiah Manchikanti

Pain Management Center of Paducah, KY USA; Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, University of Louisville, KY, USA.

Disclosure: L Manchikanti has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Mark V Boswell

Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, University of Louisville, KY, USA.

Disclosure: MV Boswell has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Joshua A Hirsch

Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital; Associate Professor of Radiology, Harvard Medical School, MA, USA.

Disclosure: JA Hirsch has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

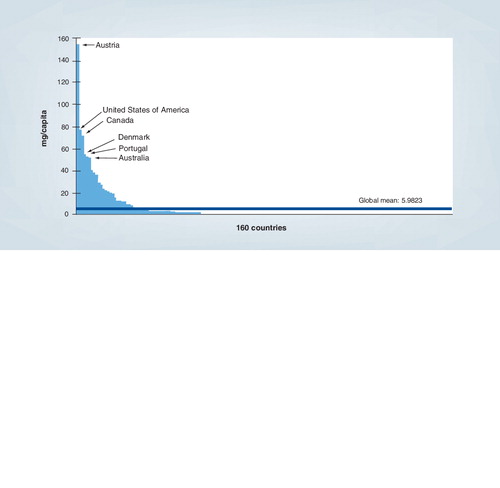

Data taken from International Narcotics Control Board, United Nations Data. Graphic created by the Pain and Policy Study Group, University of Wisconsin/WHO Collaborating Center (2009).

Data taken from Citation[33].

![Figure 2. Opioid-related deaths, 1999–2010 in all categories.Data taken from Citation[33].](/cms/asset/13453148-608c-40f4-a2f7-4ec4f573ee79/iern_a_11213059_f0002_b.jpg)

Adapted with permission from Citation[211].

![Figure 3. Deaths from unintentional drug overdoses in the USA according to major type of drug, 1999–2007.Adapted with permission from Citation[211].](/cms/asset/3551c6df-1fd9-4b39-be92-6d6134dd9a69/iern_a_11213059_f0003_b.jpg)

†Age-adjusted rates per 100,000 population for OPR deaths, crude rates per 10,000 population for OPR abuse treatment admissions and crude rates per 10,000 population for kilograms of OPR sold.

OPR: Opioid pain reliever.

Adapted with permission from Citation[33].

![Figure 4. Rates† of opioid pain reliever overdose deaths, opioid pain relief treatment admissions and kilograms of opioid pain relievers sold – USA, 1999–2010.†Age-adjusted rates per 100,000 population for OPR deaths, crude rates per 10,000 population for OPR abuse treatment admissions and crude rates per 10,000 population for kilograms of OPR sold.OPR: Opioid pain reliever.Adapted with permission from Citation[33].](/cms/asset/d127b393-3d6b-4349-9551-9b9571d34773/iern_a_11213059_f0004_b.jpg)

Adapted with permission from Citation[218].

![Figure 5. Annual societal costs of opioid abuse, dependence and misuse in the USA, 2007.Adapted with permission from Citation[218].](/cms/asset/b42ee8ae-c421-42da-8b80-88d5a512f05c/iern_a_11213059_f0005_b.jpg)

Adapted with permission from Citation[41].

![Figure 6. Percentage of patients and prescription drug overdoses, by risk group in the USA.Adapted with permission from Citation[41].](/cms/asset/ce97a697-99a1-4e0c-87ce-dd12b679b735/iern_a_11213059_f0006_b.jpg)

CT: Computed tomography.

Adapted with permission from Citation[5].

![Figure 7. Guidance to opioid therapy.CT: Computed tomography.Adapted with permission from Citation[5].](/cms/asset/4d112721-03c1-45e5-9ef7-b43f6fecc5a5/iern_a_11213059_f0007_b.jpg)

Over the past two decades the world has not only learned about, but continues to attempt to control escalating chronic pain and associated disability, as well as opioid use, abuse and related fatalities Citation[1–14]. In its 2006 report, the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) noted that medications containing narcotic or psychotropic drugs were becoming the drugs of choice for many abusers Citation[15]. They warned that the worldwide abuse of prescription drugs would soon exceed illicit drug use Citation[15]. In fact, a 2011 report of the INCB reported that abuse of prescription drugs was growing rapidly around the world with more people abusing legal narcotics than heroin, cocaine and ecstasy combined Citation[201]. It is commonly stated that there has and continues to be an escalation in the utilization of all types of interventions in managing chronic pain, but opioids and other prescription-controlled substances have taken a central role in the debate on increasing healthcare costs and related fatalities Citation[4–14,16–18]. Consequently, the overuse and abuse of prescription drugs have been emphasized as a major and growing health problem globally by leading international monitoring entities Citation[15,201–203]. Prescription drug abuse, while most prevalent in the USA, is also a problem in many areas around the world including Canada, Australia, Europe, Southern Africa and South Asia with tens of millions of people giving up control of their lives in favor of addiction Citation[11,12,15,19,201–204].

The past several years have seen soaring rates of prescription drug abuse across the USA, followed by rising numbers of deaths involving prescription drug overdoses Citation[204]. Emergency department visits related to prescription drug abuse now exceed the number of visits related to illicit drug use Citation[204]. However, it is not limited to the USA alone. Recently, it was reported that correlated to increasingly high overall prescription opioid consumption levels, nonmedical prescription opioid use and harms in Canada are high and now likely constitute the third highest level of substance-use disease burden after alcohol and tobacco Citation[11,20]. Similarly, prescription opioid analgesics and related harms in Australia have been reported Citation[12].

Casati et al. performed a systematic review of the literature concerning the misuse of medicines in the EU, which showed an alarming increase Citation[19]; multiple studies showed that opioids, sedatives and hypnotics have been extensively misused throughout Europe Citation[19]. In Germany, the estimates show that between 1.3 and 1.4 million people are dependent on prescription drugs, representing approximately 1.6 or 1.7% of the German population Citation[19]. One study showed that in Germany, approximately 25% of nursing home residents over the age of 70 are addicted to psychotropic drugs Citation[21]. In addition, of Germans over 60 years old, between 1.7 and 2.8 million misuse psychotropic drugs or pain killers or are dependent on these substances. In a cross-sectional postal survey in the UK Citation[22], the past 2-week prevalence of nonprescription analgesic use was 37%. In Spain, it has been shown that 11.6% of the subjects in one study had a lifetime prevalence for substance-use disorder related to an opioid other than heroin Citation[23]. In Denmark, a literature review showed that dependence prevalence rates for chronic nonmalignant pain patients were as high as 50%, depending on the patient population studied and the criteria used Citation[24]. In France, multiple studies showed the misuse and abuse of multiple opioids, including such drugs as transdermal fentanyl and Actiq (fentanyl citrate) Citation[19]. There are no up-to-date data available for the nontherapeutic use of psychotherapeutic drugs in other countries. Based on the report by Casati et al., in Canada, an estimated 1.3% of the population abused prescription opioids, and in several European countries – such as France, Italy, Lithuania and Poland – between 10 and 18% of students use sedatives or tranquilizers without a prescription Citation[19].

What has the medical profession learned?

Nonmedical use of psychotherapeutic drugs

The results of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health in the USA showed that in 2011, there was a 14% decline in prescription drug use for nonmedical purposes among people aged 18–25 years; this reflects the 300,000 fewer young adults abusing such drugs compared with last year’s survey Citation[205]. However, prescription abuse rates among children aged 12–17 years and adults over 26 years old remain unchanged. This survey showed that approximately 8.7% of Americans aged 12 years and older were identified as current drug users, a total of 22.5 million Americans; this was not a significant change from the previous year’s percent rate of 8.9%. Like previous years, marijuana continued to be the most commonly used illicit drug and its use appears to be on the rise. According to this survey, 7% of Americans were currently marijuana users, up from 6.9% in 2010 and 5.8% in 2007 Citation[205]. Heroin use has reduced with the number of users falling to 620,000 in 2011 from 621,000 in 2010; however, there had been a substantial increase from 373,000 users in 2007. Further, in some areas, heroin is being substituted for prescription opioids.

Overuse of therapeutic opioids

The overall production and distribution of therapeutic opioids has increased extensively in the past 20 years. Global production of morphine worldwide has more than quadrupled from 168 tons in 1993 to a projected 788 tons in 2012 Citation[25,206]. The global production of oxycodone rose by over 4000%, from approximately 6 tons in 1993 to an estimated 261 tons in 2012 Citation[25,206]. However, the data on the prevalence of opioid use among people with chronic pain, specifically moderate-to-severe chronic noncancer pain and other moderate-to-severe pain, are limited in the USA and around the globe.

From 1999 to 2002, 4.2% of US adults reported using opioid analgesics for pain within the past month Citation[207]. During the same time, opioid usage was described to be 22% of adults with pain in Canada Citation[26] and 12% in Denmark Citation[27]. A report evaluating opioid use in Utah in the USA in 2008 illustrated that 20.8% of adults in Utah had been prescribed an opioid in the last year and 29.1% of these prescriptions were for long-term pain Citation[28]. In one of the earliest surveys, opioid use was shown to have doubled from 8% in 1980 to 16% in 2000 Citation[29]. In a study of commercial and Medicaid insurance plans from 2000 to 2005, the proportion of enrollees receiving a diagnosis of chronic noncancer pain increased 33% in the HealthCore population and 99% in the Medicaid population, with a 58% increase of opioid prescriptions for chronic pain in HealthCore and 29% in Medicaid Citation[30]. Another study involving over 1% of the US population from 1997 to 2005 showed that among relevant long-term opioid users in 2005, 28.6–30.2% were also regular users of sedative hypnotics Citation[31]. This study also showed that use of long-term opioid doubled in some healthcare plans. In a study of low back pain in the USA, overall opioid use among back pain patients increased from 11.6% in 1996 to 12.6% in 1999 Citation[32]. The prescriptions showed an increase in oxycodone and hydrocodone and a decrease in propoxyphene Citation[204]. In 2008, a total of 36,450 deaths were attributed to drug poisoning, a rate of 11.9 per 100,000 population. By 2005, long-term opioid therapy was being prescribed to an estimated 10 million US adults Citation[6,33–35,208].

Elsewhere across the globe, in a study conducted in Ontario, Canada, it was illustrated that from January 1991 to May 2007, opioid analgesic prescriptions increased by 29%, from 458 to 591 prescriptions, per 1000 individuals annually Citation[36]. The number of oxycodone prescriptions rose more than 850% during the same period, from 23 per 100,000 individuals in 1991, to 197 per 100,000 in 2007. The addition of long-acting oxycodone to the drug formulary was associated with a fivefold increase in oxycodone-related mortality and a 41% increase in overall opioid-related mortality. Multiple authorities have looked at the relationship between increasing controlled substance use, specifically opioid use and related fatalities.

In pain management settings, it has been reported that as many as 90% of patients receive opioids for chronic pain management Citation[4–6,37]. In addition, it also has been illustrated that the majority of these patients were on opioids prior to presenting to an interventional pain management setting Citation[37]. Furthermore, Deyo et al. illustrated that approximately 20% of patients in primary care settings were long-time opioid users with 61% receiving a course of opioids Citation[38]. Multiple studies also have described that many of the patients in primary care settings also abuse illicit drugs Citation[38].

The quadrupled sales of opioid analgesics between 1999 and 2010 are a perfect example of the therapeutic opioid explosion. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, in 2009, a handful of countries – the USA, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and several European countries – used 90% of the morphine, fentanyl and oxycodone used around the globe Citation[39]. This finding was echoed by the WHO; using 2003 figures from the INCB, they reported 79% of worldwide morphine use was accounted for by just six developed countries; the numbers were reversed when developing countries, comprising 80% of the world’s population, were shown to only use 6% Citation[39]. As shown in , there were similar findings in 2007 when six developed countries had the highest morphine consumption while 132 out of 160 countries were below the worldwide mean consumption for morphine.

These findings expose the disparity in pain relief that patients receive between developed and developing countries. Moderate-to-severe pain patients by the millions are undertreated in developing countries, while in developed countries, these same patients are overtreated with opioids, especially in the USA, which consumes an incredible 99% of all hydrocodone and 83% of all oxycodone Citation[38]. On a per-gram basis, those in the USA use more narcotics than any other country. The INCB estimates global pharmaceutical companies produce more than 75-times a year of oxycodone, compared with 11.5-times in 1999, of which more than 80% is consumed in the USA Citation[202,203]. In addition, the US demand for hydrocodone – the most commonly prescribed opioid – dwarfs what is consumed by the rest of the world: 27.4 million grams each year for the USA alone versus 3237 g for Great Britain, Germany, Italy and France combined Citation[4–6,202,203].

Opioid sales in the USA increased sevenfold from 1997 to 2010 from morphine equivalents of 96 mg per person to 710 mg per person Citation[38]. Put another way, enough opioids are sold so that 15 mg of hydrocodone can be administered every day to every American adult for 47 consecutive days. In the 10-year period from 1997 to 2007, hydrocodone sales jumped 280%, methadone jumped 1293% and oxycodone jumped 866% in the USA .

Both immediate-release (IR) and extended-release (ER) opioid prescriptions have increased in the USA. A staggering 256 million opioid prescriptions were filled out in 2009, of which 234 million were IR (compared with only 223.9 million 2 years earlier) and 22.9 million were ER (compared with 21.3 million 2 years earlier) Citation[209].

These data also illustrate an eightfold increase in stimulant prescriptions from 1991 to 2009 Citation[209]. A recent publication showed that 94% of patients presenting to an interventional pain management program were on long-term opioids in the USA Citation[37]. Illicit drug use was also common, in patients presenting to an interventional pain management program although, it has declined significantly from a previous publication. While a large proportion of individuals (45.7%) have used illicit drugs at some point, current illicit drug use was present in only 7.9% of patients; both past and current use was similar to that of the general population. More importantly, a significant proportion of patients (48.8%) have been on opioids (high doses of more than 40 mg equivalents of morphine) on a long-term basis, initiated and maintained by primary care physicians; 35% were on benzodiazepines and 9.2% on carisoprodol prior to presenting to interventional pain management.

Consequences of excessive opioid use

The number of deaths in the USA ascribed to prescription drugs is staggering, including those caused by opioids. In 2008, 36,450 deaths were credited to a drug overdose. Of these, a specific drug was attributed in 27,153 deaths, and of these, one or more prescription drugs were implicated in 20,044 deaths; 14,800 of these 20,044 deaths involved opioids Citation[33]. In fact, published on 19 February 2013, the latest report from the CDC showed that continuing a trend that began more than a decade ago, in 2010, 16,651 people died of overdoses involving prescription opioids compared with 4030 such deaths in 1999, an increase of 313.2%. The CDC researchers once again wrote that this analysis confirms the predominant role opioid analgesics play in pharmaceutical overdose deaths, either alone or in combination with other drugs Citation[40]. Opioid analgesics caused more overdose deaths in 2007 than heroin and cocaine combined Citation[41,210–212]. Concurrently, suicide caused by drugs increased; by 2007, there were 8400 overdose deaths in the USA that were either suicide or the deceased’s intent could not be ascertained. Approximately 3000 of those deaths involved opioids Citation[34]. In addition, for every unintentional opioid analgesic overdose death, nine were admitted for substance abuse treatment, 35 visited emergency departments, 161 reported drug abuse or dependence and 461 reported nonmedical use of opioid analgesics Citation[41]. Furthermore, in 2007, non-suicidal drug poisoning deaths not related to suicide exceeded either motor vehicle accidents or suicide deaths in 20 states with data from Ohio illustrating the number of deaths from unintentional drug poisoning exceeding the numbers of deaths from both suicide and motor vehicle accidents combined Citation[34,212]. A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report also concluded that key measures of prescription pain-reliever abuse and misuse increased from 2003 to 2009 Citation[210]. Consequently, a conclusion has been reached by many that opioid analgesic abuse contributed to increasing fatalities based on opioid abuse and increasing doses, doctor shopping and other aspects of drug abuse as illustrated in Citation[33]. Furthermore, the data from emergency department visits also illustrate that the use of opioids, sedatives and nonprescription sleep aids taken more than prescribed medication or solely for the feeling they cause continued to increase through 2009 Citation[4–6,41].

Opioid abuse has been fueled by multiple factors including legitimate and easy availability in rural as well as urban areas, high street values and comorbid mental illnesses Citation[4–6,34].

How did we get here?

Opioid prescriptions for chronic noncancer pain skyrocketed in the late 1990s. The primary driver was the lifting of restrictions on opioid prescribing by state medical boards Citation[213]. Once these restrictions were lifted, other changes occurred, resulting in runaway opioid prescriptions. Among the changes were new standards for both inpatient and outpatient pain management, implemented in 2000 by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations Citation[42] and the concept of a patient’s right to pain relief, resulting in the validation physicians needed to increase their opioid prescribing Citation[4–6].

With the door open to acceptance, those with vested interests in opioid prescribing jumped into action. The pharmaceutical industry unleashed their marketing machine, many physicians promoted opioids and a number of organizations called for increasing opioid treatment for patients with chronic noncancer pain Citation[4–6]. However well meaning, these positions were based on misinformation and unsound science; the justification for increased opioid prescribing was that it was safe and effective so long as the opioids were prescribed by a physician Citation[4–6,38,39,214].

One irony to come out of this groundswell of support for opioid prescribing is that many model guidelines, whose intent was to curtail controlled substance abuse, actually appeared to condone an increase in opioid prescribing Citation[4–6,43]. One guideline seems to absolve prescribers from the responsibility for their actions: ‘no disciplinary action will be taken against a practitioner based solely on the quantity and/or frequency of opioids prescribed’ Citation[213].

The result of all these factors is that opioid prescribing, including long-acting and potent forms, has increased exponentially. This increase has been driven by regulations based on weak evidence that opioids are highly effective and safe, especially when administered to those with chronic noncancer pain, as well as questionable selection criteria Citation[4–6,214].

Today, there is still no unmistakable scientific evidence that opioids are effective for chronic noncancer pain Citation[4–6,43–53,214]. Opioids’ lack of effectiveness is not the only troubling concern regarding chronic opioid therapy. There is mounting evidence that opioids have multiple physiological and nonphysiological adverse effects including: opioid-induced hyperalgesia, misuse and abuse, providers not trained to identify or monitor their patients for misuse and overuse and fatalities related to opioids, which have steadily been climbing Citation[4–6,43–75,214–217].

The steady increase in fatalities caused by opioids, coupled with the scant evidence for their effectiveness, begs the question of who will be held responsible for opioids being adopted prematurely as a treatment standard Citation[4–6]. Some have predicted that there will be a ‘postmortem’ on runaway opioid prescribing and the social ills that have accompanied it. Among those social ills are the damage done by opioid diversion, misuse and abuse. Prescribing opioids for chronic noncancer pain violates a sacred principle of medical intervention – there should be convincing evidence of a treatment’s benefit before its large-scale use.

Impact on healthcare costs

Strassels described the economic burden of prescription opioid misuse and abuse in a comprehensive review Citation[14]. He described that estimating the incidence of consequences of opioid misuse, abuse and diversion from biomedical literature is challenging. The author identified over 2300 titles, included 41 in the review and showed that the total cost of prescription opioid abuse in 2001 was estimated at US$8.6 billion, including workplace, healthcare and criminal justice expenditures.

The existing evidence indicates that persons who abuse or misuse prescription opioids incur higher costs and healthcare resource use. A study of commercially insured beneficiaries in the USA found that mean per capita annual direct healthcare costs from 1998 to 2000 were nearly US$16,000 for abusers of prescribed and nonprescribed opioids compared with approximately US$1800 for nonusers who had at least one prescription insurance claim Citation[76]. The study’s authors concluded that the economic burden of prescription opioid misuse and abuse is large. Furthermore, when examined by category, inpatient expenditures accounted for 46% of the total cost for abusers and 17% for nonabusers. In addition, opioid abusers were four-times as likely to visit the emergency department, had 12-times as many hospital stays and three-times as many outpatient visits than nonabusers. A study prepared for the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) reported that the cost of drug abuse in the USA in 2002 was estimated to be US$180.8 billion Citation[76]. This estimate included resources used to address health and crime consequences and loss of productivity resulting from disability, deaths and withdrawals from the workforce, but does not specify the contribution of illicit use of prescription opioid analgesics to the total economic burden.

Birnbaum et al., in an analysis of the costs of prescription opioid abuse, separately assessed healthcare, workplace and criminal justice expenditures Citation[77]. In this study, the total economic burden was estimated at US$8.6 billion in 2001; healthcare costs accounted for 30% of the total burden. Birnbaum et al. also assessed the societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence and misuse in the USA Citation[78]. Once again, they identified costs by healthcare, workplace and criminal justice expenditures. They estimated the total US societal costs of prescription opioid abuse at US$55.7 billion in 2007; healthcare costs accounted for US$25 billion or 45% of total costs. These healthcare costs consisted primarily of excess medical and prescription costs, valued at US$23.7 billion. They concluded that the cost of prescription opioid abuse presents a substantial and growing economic burden for society.

The 2007 Treatment Episodes Data Set reported that the number of patients admitted to substance abuse treatment facilities due to nonheroin/opioid abuse nearly quadrupled from 23,000 to more than 90,000 from 1999 to 2007 Citation[218]. shows the growing prevalence of prescription opioid abuse, dependence and misuse and shows the annual societal costs of opioid abuse, dependence and misuse in the USA in 2007.

Patients who abuse opioids accounted for over 92% of excess medical and drug costs with their caregivers accounting for the remainder. Medicaid patients and caregivers combined contributed approximately a third of total excess medical and drug costs, privately insured and uninsured patients and caregivers contributed slightly less than a third each and Medicare patients and caregivers accounted for only 4.6% Citation[78].

Similar to the above reports, in 2006, the estimated total cost in the USA of the nonmedical use of prescription opioids was US$53.4 billion. Five drugs, including OxyContin (an ER version of oxycodone), oxycodone, hydrocodone, propoxyphene and methadone accounted for two-thirds of the total economic burden Citation[79]. The CDC in 2008 reported that the cost of pain killer abuse can exceed US$70 billion annually, not including the social problems they perpetuate or the lost or stalled potentials of those addicted to them. It has also been shown that opioid abusers generate, on average, annual direct healthcare costs 8.7 times higher than nonabusers Citation[219,220].

In addition to federal programs, Medicaid, workers’ compensation and private insurers are also involved. The prevalence of opioid abuse is estimated to be over ten-times higher for Medicaid beneficiaries than private insurance populations Citation[80]. A Washington state study of opioid deaths involving prescription drugs between 2004 and 2007 found that 1668 persons died from prescription opioid-related overdoses during the time period with 6.4 deaths per 100,000 population per year; 45.4% of deaths were among persons enrolled in Medicaid Citation[81]. In another study, it was shown that escalating problems such as overdose, addiction and even death were reported in association with workers’ compensation claims, with 55–85% of injured workers across the country receiving opioids for chronic pain relief Citation[82]. The report found workers’ compensation claims in the state of Michigan, USA, which included prescriptions for certain opioid medications were nearly four-times more likely to develop into catastrophic claims. The study also determined that opioid use was an independent predictor of whether a compensation claim would generate costs greater than US$100,000.

The cost of substance abuse in general in the USA was reported in 2005 with federal, state and local government spending as a result of substance abuse and addiction being at least US$467.7 billion Citation[221]. Almost three-quarters (71.1%) of total federal and state spending on substance abuse was in two areas: healthcare and justice system costs. Reports published in the USA show an escalating problem of prescription drug use, abuse and diversion in the Medicare and Medicaid programs Citation[222].

Increasing healthcare costs and increasing misuse and related costs in Canada have been described. Canada is home to the overall second highest level of prescription opioid use globally. Total prescription opioids consumed in Canada increased from 8713 standardized, defined daily-doses in 2002 to 26,380 standardized, defined daily-doses in 2008–2010 – a 203% increase, which appears to be steeper than that observed in the USA Citation[206].

Roxburgh et al., whilst describing prescription opioid analgesics and related harms in Australia, were concerned with the growing use of opioids among medical professionals and the increase in opioid analgesic prescriptions, specifically morphine and oxycodone, over the past decade Citation[12]. While North America ranks first, Australia’s consumption of opioid analgesics is ranked 10th internationally; however, per capita consumption of oxycodone and morphine preparations in Australia is relatively high, ranked third and fifth respectively, internationally, compared with Canada, which ranks first for oxycodone and Australia, which ranks first for morphine Citation[201]. This study showed prescriptions for morphine declined, while those for oxycodone increased markedly. Further, prescriptions for both were highest among older Australians. They reported 465 oxycodone-related deaths from 2001 through 2009. While treatment episodes for problematic morphine use remained relatively stable with 0.07 per 1000 population in 2007–2008, episodes for problematic oxycodone use doubled, from 0.01 per 1000 population in 2002–2003 to 0.02 per 1000 population in 2007–2008 Citation[12].

Promoting pain treatment, including using opioids, is endorsed by the Institute of Medicine committee. Despite this, they recognize that there is a serious crisis with opioid abuse and diversion, as well as the fact that chronic opioid therapy has not been proven viable for treating chronic pain. The opioid crisis continues to accelerate, as does chronic pain’s prevalence, healthcare costs and adverse consequences from opioids Citation[4–6]. Even with such mounting evidence, there are still those who advocate increased opioid use based on a supposed undertreatment of pain. In fact, Stein et al. summarized the evidence succinctly, noting that ‘many arguments in favor of opioids are solely based on traditions, expert opinion, practical experience, and uncontrolled anecdotal observations’ Citation[50].

The CDC have reported the percentage of patients with prescription drug overdoses by risk-group in the USA Citation[41]. This report showed that approximately 80% were prescribed low doses (<100-mg of morphine equivalent dose per day) by a single practitioner. These account for only an estimated 20% of all prescription overdoses . By contrast, among the remaining 20% of patients, the 10% prescribed high doses of opioids by single prescribers (>100-mg morphine equivalent dose per day) Citation[83,84], account for an estimated 40% of prescription opioid overdoses Citation[62,85] and the remaining 10% of patients seeing multiple doctors and typically involved in drug diversion, account for 40% of overdoses Citation[73]. In fact, 76% of nonmedical users report obtaining drugs that had been prescribed to someone else while only 20% report that they acquired the drug from their own doctor Citation[41]. Finally, among persons who died of opioid overdoses, a significant proportion did not have a prescription in their records for the opioid that killed them; in West Virginia, Utah and Ohio (USA), 25–66% of those who died of pharmaceutical overdose used opioids originally prescribed to someone else Citation[73,86,212].

Thus, in modern medicine, adverse consequences of appropriately prescribed and used opioids are underappreciated with all the blame diverted to abuses and overuses. This is, in addition to the lack of evidence regarding the long-term benefits, the alarming evidence that the increased prescribing of opioids is fueling an epidemic of addiction and overdose deaths, based on a lack of education and misinformation, leading essentially to overprescribing Citation[211]. Due to multiple adverse consequences with opioids even when they are prescribed appropriately, a more cautious stance towards opioid prescribing for chronic noncancer pain has been advocated Citation[4–6,38,41,44–48,57,60,61,87,88,208,210,214]. In fact, the majority of injuries and deaths may arise from people using opioids exactly as prescribed, not just those misusing or abusing them Citation[214]. It is even more important that most studies indicate that patients on long-term opioid therapy are unlikely to stop them, even if analgesia and function are poor and safety issues arise Citation[6]. On the other hand, patients also report excellent pain relief and improvement in function with other modalities or interventions Citation[88,89].

Taking higher doses and a combination of short-acting and long-acting opioids are likely to be abused and also cause serious dose-related adverse effects, including death. In addition, there is no evidence to support the previous teaching that long-acting opioids can provide better analgesia and less abuse risk than IR products Citation[6,33,44–49,214].

Multiple studies have reported an association between opioid prescribing and overall health status with increased disability, increased medical costs, subsequent surgery and continued or late opioid use Citation[4–6,34,77,88–100]. Overall, it appears that epidemiologic studies are less positive regarding functional improvement and quality-of-life for chronic pain patients on opioids Citation[100]. In Denmark, where opioids are freely prescribed for chronic pain, an epidemiological study conducted Citation[88] showed that those receiving opioids for chronic pain, when compared with a matched cohort of chronic pain patients not receiving opioids, had higher pain levels, higher healthcare utilization and lower activity levels Citation[101].

Curtailing opioid abuse & healthcare costs

Opioid abuse and extensive use may be curtailed by various means. The first and foremost is to close pill mills and promote responsible opioid prescribing by educating physicians and the public. It is essential to realize that psychotherapeutic drug abuse, including opioids, is superseding illicit drug use. Drug dealers are no longer the primary source of illicit drugs. It appears that the greatest problem now is diversion through family and friends; their source is more likely to be one physician, not doctor shopping. Further, consideration must be given to the highly interactive pattern of effect and impact that exists in the general area of substance abuse, mental health and overall healthcare.

Misuse, abuse and diversion should be addressed on four fronts: education, establishing medical necessity, supply and drugs.

Supply is dependant on physicians and patients, thus education of both is extremely important. The increased abuse of opioid analgesics likely reflects the misguided belief that, because these medications are prescribed by physicians, they are safer than illicit drugs. It is also likely that part of this increased abuse is due to much greater access to and availability of opioid analgesics Citation[86,102]. This is likely to reflect more aggressive management of noncancer pain, facilitated, in part, by the regulatory mandate from Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, liberalization of medical board regulations, and by lingering concerns regarding the safety of non-opioid analgesics and their tolerability Citation[102].

Education and knowledge can be a double-edged sword. Physicians must recognize that some patients misrepresent genuine pain in order to obtain, misuse and divert these medications, resulting in serious or even lethal public health problems Citation[102]. Thus, enhancing and updating clinical teaching and training for physicians, nurses, dentists and pharmacists in the areas of pain management, opioid pharmacology and abuse/addiction, perhaps through interactive web-based training, should be the first and foremost line of action Citation[102]. It has been suggested that pain management education for health professionals has been and continues to be insufficient. Consequently, a more comprehensive and contemporary curriculum for prescribers seems warranted Citation[102]. Appropriate guidance must be applied because, as the literature illustrates, guidelines do not sufficiently influence clinical practice of opioid prescribing in chronic pain management. The lack of appropriate guidelines and education leads to stringent regulations enacted by legislators that mainly focus on curtailing abuse, which may also reduce access to needed therapy. Education is of paramount importance to curtail and properly manage opioid use and abuse.

Education and understanding the physiology and pharmacology of chronic pain and the multiple modalities available for managing it, as well as comorbid factors, will assist physicians in establishing indications and medical necessity for chronic opioid therapy. Prior to initiating opioid therapy, it requires a comprehensive initial evaluation, including a screening process and special provisions for managing pain and those most at risk for abuse and dependence, a family history of substance abuse disorders and alcohol abuse, evaluation of the previous history through prescription monitoring program (PMP) results or results from physicians when the PMP is not available, baseline urine drug testing, and, finally, initiation of monitoring for adherence.

Medical necessity is a dynamic process. This includes assessing and establishing other treatment modalities such as physical and behavioral modalities, assessing the risk–benefit ratio of opioid therapy, establishing treatment goals, obtaining informed consent and agreements, titrating the initial dose, maintaining through stable phases and monitoring adherence. Further, outcomes must be assessed on a regular basis once medical necessity is established and opioid therapy may be discontinued either for nonadherence or failure to respond. Supply is closely tied to adherence monitoring. Adherence monitoring consists of continuous vigilance from the initial evaluation to discharge utilizing numerous means including screening tools, urine drug testing, PMPs and appropriate agreements or contracts.

PMPs collect state-wide data about prescription drugs and track their flow. To date, 48 states have approved PMPs, but there is a significant difference in the manner and frequency with which the data are collected. The National All Schedules Prescription Electronic Reporting was signed into law in 2005, created by the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians and enacted by Congress Citation[223]. This law requires states to collect prescription information for Schedule II, III and IV medications. It also requires states to have the capability to share this information with one another. This can decrease cross-border narcotic trafficking. Even though there is no definite evidence that PMPs reduce overuse and abuse, partly due to interstate commerce laws and a multitude of other issues, most appreciate the benefit of monitoring programs and the ability to make proper decisions with information in hand in conjunction with other regulations Citation[4–6,41,103–105].

Consequently, multiple screening tools to monitor opioid adherence have been developed for predicting and identifying aberrant drug-related behaviors Citation[4–8]. The majority of the screening tools used to evaluate pain are based on psychopathology, but some also assess drug misuse and abuse. There is currently no ideal instrument that can screen for misuse and abuse of drugs while also being able to reliably predict the potential for substance abuse.

Urine drug testing is part of adherence monitoring to curtail the abuse of opioids as well as other controlled substances Citation[67–71]. Urine drug testing provides relatively good specificity, sensitivity, ease of administration and cost; however, controversies exist regarding the clinical value of urine drug testing, partly because most current methods are designed for, or adapted from, forensic or occupational deterrent-based testing for illicit drug use and are not entirely optimal for application in chronic pain management settings. Furthermore, additional issues exist related to excessive use, misuse, abuse and financial incentives Citation[70]. However, recent diagnostic accuracy reports of urine drug testing illustrated that immunoassay in an office setting is appropriate, convenient, and cost effective Citation[69]. With appropriate monitoring tools, this can be performed cost effectively without laboratory confirmation in the majority of the patients unless the patient does not provide a proper history and the problem of abuse continues.

The fourth issue in curtailing opioid abuse is the development of abuse deterrent formulations (ADFs) of opioids. This can potentially curtail abuse but still have opioids readily available for pain management for those who need them. The potential for abuse depends on the formulation, route of administration and rapid rise of plasma concentration resulting in drug linking and reinforcement Citation[67]. Various types of ADFs of opioids are being developed, but they will not necessarily decrease abuse in those who consume the drug intact. Some ADFs employ physical barriers that resist common methods of tampering, such as crushing the pill and subjecting the pill to various chemical manipulations to extract the active ingredients so that they can be chewed. A combination of opioid agonists and opioid antagonists have also been tried; however, these have not been very successful.

A GAO report extensively dealt with opioid abuse and recommended that the director of the ONDCP establish outcome metrics and implement a plan to evaluate proposed educational efforts and ensure that agencies share lessons learned among similar efforts. The ONDCP did not explicitly agree or disagree with the GAO’s recommendations, but noted that it will continue to work for improved coordination of educational efforts and evaluation of outcomes.

Franklin et al. showed that this guidance is effective in bending prescription opioid dosing and reducing mortality Citation[106]. This study, showed a substantial decline in both the morphine equivalent dose per day of long-acting schedule II opioids by 27% and the proportion of workers on doses equal to or greater than 120-mg per day of morphine equivalent dosage by 35%, compared prior to 2007 Citation[106]. Furthermore, there was also a 50% decrease from 2009 to 2010 in the number of deaths.

Guidelines provide different types of recommendations; however, none are based on evidence and most of them are based on consensus. Appropriate guidelines are an approach developed in each practice and must include the following: standardized screening procedures and special provisions for managing pain in those most at risk for abuse and dependence, including adolescents and young adults, individuals with a current or previous substance-use disorder, including nicotine and alcohol, and individuals with a family history of substance use disorders Citation[102]. In addition, the guidelines should have indications for when and how long to prescribe non-opioid analgesics, or nonpharmacological methods or both for pain control versus when and for how long to prescribe opioid analgesics. Other indications should include when short- versus long-acting opioids should be prescribed and reasonable limits on the number of pills or amount of liquid prescribed, such that the prescribed amounts match the number of treatment days required.

Furthermore, an approach for continuing opioid pain management for chronic noncancer pain should include the following: when and how to use urine screening to manage the risk of diversion, abuse and addiction; when and how to use patient contracts to manage risk of diversion through a single-source prescriber and pharmacies; proper use of state prescription drug monitoring programs to reduce doctor shopping; criteria for deciding how long a patient should receive opioid analgesics and criteria for deciding whether and under what circumstances to refill or discontinue opioid prescriptions Citation[102].

Since the patient is a crucial part of the abuse, overuse or diversion, patients and the general public must also be educated and made more aware and responsible for the use, storage and disposal of opioid analgesics Citation[102]. Furthermore, the media should evaluate the influence of news reporting on the popularity of and misconceptions about psychoactive substances, particularly prescription opioids Citation[102]; the media can be influential in curtailing abuses Citation[4,5].

illustrates practical steps in managing chronic opioid therapy for noncancer pain in an algorithmic fashion. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians guidelines and subsequent literature about the efforts of PMPs through National All Schedules Prescription Electronic Reporting and education are based on understanding various aspects of chronic pain and its management.

Following the appropriate recommendations with better education and appropriate prescription patterns should reduce misuse, abuse, overuse and diversion, while at the same time, promote proper pain management while maintaining access. Thus, it may be possible to not only curtail abuse, but also continue to provide appropriate avenues for proper pain management. This can be achieved with higher education standards for physicians, the public and legislators; cooperation from the pharmaceutical industry to curtail aggressive promotion; and clear and positive guidelines from regulators.

Expert commentary

Physicians have dramatically increased their prescribing of opioids for chronic noncancer pain over the past two decades. However, this change in practice and escalating use of opioids was driven by factors unrelated to their effectiveness. Even though physicians and the general public were given the impression that long-term opioid therapy had been proven safe and effective for chronic noncancer pain, the evidence indicates otherwise. Without showing significant effectiveness and with major adverse effects, patients may continue to experience significant chronic pain and dysfunction despite opioid therapy. The lack of evidence regarding its benefits and adverse effects, coupled with strong evidence for increased opioid prescribing, is fueling an epidemic of addiction and overdose deaths.

Addressing the problem of curtailing opioid abuse, while maintaining access to these drugs for patients in need of them, requires appropriate evaluation and monitoring. Critical factors in chronic opioid use relate to various issues with education taking priority, followed by adherence monitoring through PMPs, urine drug testing and vigilance and finally achieving a balance between curtailing opioid abuse and overuse, and meeting appropriate needs.

Five-year view

Based on the available data, it appears that there are multiple strides being made in the area of education to curtail opioid abuse and understand their appropriate use. In the next 5 years, we believe that there will be an escalation of numerous regulations from the Drug Enforcement Administration, US FDA, boards of medical licensure or similar agencies globally as well as legislatures. We may also see major developments in the area of ADFs and appropriate dispensing of medications through a proper mechanism with tamper-resistant dispensers. Thus, when education, supply, demand and drugs are implemented in combination, in the next 5 years, a reasonable approach may be developed to curtailing abuse, while at the same time improving access and effective management. While it is a basic necessity for physicians to use all skills to relieve pain and suffering, while also doing no harm, it is also essential to consider various modalities of treatments including cognitive behavioral therapy. As the Institute of Medicine described, effective pain management, while essential, is never about the clinician’s intervention alone, but about the clinician, and patient and their family working together.

Table 1. Retail sales of opioid medications (grams of medication) from 1997 to 2007.

Key issues

• Chronic pain, disability and opioid use and abuse are highly prevalent and expensive across the world.

• There have been dramatic increases in the prescribing of opioids for noncancer pain over the past two decades, which coincides with various factors including the liberalization of regulations, new standards by Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, aggressive marketing by the pharmaceutical industry and a belief that opioids are safe and effective when prescribed by physicians and taken appropriately.

• Drug poisoning deaths are escalating; from 16,849 in 1999 to 36,500 in 2008 in the USA.

• For every unintentional overdose death related to an opioid analgesic, nine persons were admitted for substance abuse treatment, 35 visited emergency departments, 161 reported drug abuse or dependence and 461 reported the nonmedical use of opioid analgesics in 2007.

• Implementing strategies that target those persons at greatest risk will require strong coordination and collaboration at the federal, state and local levels, as well as the engagement of healthcare professionals, policy-makers, patients and the public at large.

• Education, supply, demand and drugs are crucial factors in curtailing abuse and promoting appropriate use.

References

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, USA (2011).

- Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Agans RP et al. The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain. Arch. Intern. Med. 169(3), 251–258 (2009).

- Hoy DG, Protani M, De R, Buchbinder R. The epidemiology of neck pain. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 24(6), 783–792 (2010).

- Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S et al.; American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic noncancer pain: part I – evidence assessment. Pain Physician 15(Suppl. 3), S1–S65 (2012).

- Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S et al.; American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic noncancer pain: part 2 – guidance. Pain Physician 15(Suppl. 3), S67–S116 (2012).

- Manchikanti L, Helm II S, Fellows B et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician 15(Suppl. 3), ES9–ES38 (2012).

- Koyyalagunta D, Bruera E, Solanki DR et al. A systematic review of randomized trials on the effectiveness of opioids for cancer pain. Pain Physician 15(Suppl. 3), ES39–ES58 (2012).

- Sehgal N, Manchikanti L, Smith HS. Prescription opioid abuse in chronic pain: a review of opioid abuse predictors and strategies to curb opioid abuse. Pain Physician 15(Suppl. 3), ES67–ES92 (2012).

- Owen GT, Burton AW, Schade CM, Passik S. Urine drug testing: current recommendations and best practices. Pain Physician 15(Suppl. 3), ES119–ES133 (2012).

- Atluri S, Akbik H, Sudarshan G. Prevention of opioid abuse in chronic noncancer pain: an algorithmic, evidence based approach. Pain Physician 15(Suppl. 3), ES177–ES189 (2012).

- Fischer B, Argento E. Prescription opioid related misuse, harms, diversion and interventions in Canada: a review. Pain Physician 15(Suppl. 3), ES191–ES203 (2012).

- Roxburgh A, Bruno R, Larance B, Burns L. Prescription of opioid analgesics and related harms in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 195(5), 280–284 (2011).

- Manubay JM, Muchow C, Sullivan MA. Prescription drug abuse: epidemiology, regulatory issues, chronic pain management with narcotic analgesics. Prim. Care 38(1), 71–90, vi (2011).

- Strassels SA. Economic burden of prescription opioid misuse and abuse. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 15(7), 556–562 (2009).

- Kuehn BM. Prescription drug abuse rises globally. JAMA 297(12), 1306 (2007).

- Gupta S, Gupta M, Nath S, Hess GM. Survey of European pain medicine practice. Pain Physician 15(6), E983–E994 (2012).

- Manchikanti L, Falco FJ, Singh V et al. Utilization of interventional techniques in managing chronic pain in the Medicare population: analysis of growth patterns from 2000 to 2011. Pain Physician 15(6), E969–E982 (2012).

- Martin BI, Turner JA, Mirza SK, Lee MJ, Comstock BA, Deyo RA. Trends in health care expenditures, utilization, and health status among US adults with spine problems, 1997–2006. Spine 34(19), 2077–2084 (2009).

- Casati A, Sedefov R, Pfeiffer-Gerschel T. Misuse of medicines in the European Union: a systematic review of the literature. Eur. Addict. Res. 18(5), 228–245 (2012).

- Shield KD, Ialomiteanu A, Fischer B, Rehm J. Assessing the prevalence of non-medical prescription opioid use in the Canadian general adult population: evidence of large variation depending on survey questions used. BMC Psychiatry 13, 6 (2013).

- Stafford N. At least 25% of elderly residents of German nursing homes are addicted to psychotropic drugs, report claims. BMJ 340, c2029 (2010).

- Porteous T, Bond C, Hannaford P, Sinclair H. How and why are non-prescription analgesics used in Scotland? Fam. Pract. 22(1), 78–85 (2005).

- Astals M, Domingo-Salvany A, Buenaventura CC et al. Impact of substance dependence and dual diagnosis on the quality of life of heroin users seeking treatment. Subst. Use Misuse 43(5), 612–632 (2008).

- Højsted J, Sjøgren P. Addiction to opioids in chronic pain patients: a literature review. Eur. J. Pain 11(5), 490–518 (2007).

- International Narcotics Control Board. Narcotic Drugs: Estimated World Requirement for 2001 – Statistics for 1999. United Nations, New York, NY, USA (2000).

- Moulin DE, Clark AJ, Speechley M, Morley-Forster PK. Chronic pain in Canada – prevalence, treatment, impact and the role of opioid analgesia. Pain Res. Manag. 7(4), 179–184 (2002).

- Eriksen J, Jensen MK, Sjøgren P, Ekholm O, Rasmussen NK. Epidemiology of chronic non-malignant pain in Denmark. Pain 106(3), 221–228 (2003).

- CDC. Adult use of prescription opioid pain medications – Utah, 2008. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 59(6), 153–157 (2010).

- Caudill-Slosberg MA, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Office visits and analgesic prescriptions for musculoskeletal pain in US: 1980 vs 2000. Pain 109(3), 514–519 (2004).

- Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Fan MY, Devries A, Brennan Braden J, Martin BC. Trends in use of opioids for noncancer pain conditions 2000–2005 in commercial and Medicaid insurance plans: the TROUP study. Pain 138(2), 440–449 (2008).

- Elliott AM, Smith BH, Penny KI, Smith WC, Chambers WA. The epidemiology of chronic pain in the community. Lancet 354(9186), 1248–1252 (1999).

- Luo X, Pietrobon R, Hey L. Patterns and trends in opioid use among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine 29(8), 884–890; discussion 891 (2004).

- CDC. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers – United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 60(43), 1487–1492 (2011).

- Paulozzi LJ, Weisler RH, Patkar AA. A national epidemic of unintentional prescription opioid overdose deaths: how physicians can help control it. J. Clin. Psychiatry 72(5), 589–592 (2011).

- Boudreau D, Von Korff M, Rutter CM et al. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 18(12), 1166–1175 (2009).

- Dhalla IA, Mamdani MM, Sivilotti ML, Kopp A, Qureshi O, Juurlink DN. Prescribing of opioid analgesics and related mortality before and after the introduction of long-acting oxycodone. CMAJ 181(12), 891–896 (2009).

- Manchikanti L, Cash KA, Malla Y, Pampati V, Fellows B. A prospective evaluation of psychotherapeutic and illicit drug use in patients presenting with chronic pain at the time of initial evaluation. Pain Physician 16(1), E1–E13 (2013).

- Deyo RA, Smith DH, Johnson ES et al. Opioids for back pain patients: primary care prescribing patterns and use of services. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 24(6), 717–727 (2011).

- Ensuring availability of controlled medications for the relief of pain and preventing diversion and abuse: striking the right balance to achieve the optimal public health outcome. Discussion paper based on a scientific workshop. UNODC, Vienna, Austria, 18–19 January 2011.

- Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA 309(7), 657–659 (2013).

- CDC. CDC grand rounds: prescription drug overdoses – a US epidemic. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 61, 10–13 (2012).

- Phillips DM. JCAHO pain management standards are unveiled. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. JAMA 284(4), 428–429 (2000).

- Fauber J. Painkiller boom fueled by networking. J. Sentinel (2012).

- Chou R, Huffman L. Guideline for the Use of Chronic Opioid Therapy in Chronic Noncancer Pain: Evidence Review. American Pain Society, Glenview, IL, USA (2009).

- Manchikanti L, Ailinani H, Koyyalagunta D et al. A systematic review of randomized trials of long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain. Pain Physician 14(2), 91–121 (2011).

- Noble M, Treadwell JR, Tregear SJ et al. Long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD006605 (2010).

- Kalso E, Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Opioids in chronic noncancer pain: systematic review of efficacy and safety. Pain 112(3), 372–380 (2004).

- Furlan AD, Sandoval JA, Mailis-Gagnon A, Tunks E. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: a meta-analysis of effectiveness and side effects. CMAJ 174(11), 1589–1594 (2006).

- Manchikanti L, Vallejo R, Manchikanti KN, Benyamin RM, Datta S, Christo PJ. Effectiveness of long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain. Pain Physician 14(2), E133–E156 (2011).

- Stein C, Reinecke H, Sorgatz H. Opioid use in chronic noncancer pain: guidelines revisited. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 23(5), 598–601 (2010).

- Von Korff M, Kolodny A, Deyo RA, Chou R. Long-term opioid therapy reconsidered. Ann. Intern. Med. 155(5), 325–328 (2011).

- Reinecke H, Sorgatz H; German Society for the Study of Pain (DGSS). S3 guideline LONTS. Long-term administration of opioids for nontumor pain. Schmerz 23(5), 440–447 (2009).

- Sorgatz H, Maier C. Nothing is more damaging to a new truth than an old error: conformity of new guidelines on opioid administration for chronic pain with the effect prognosis of the DGSS S3 guidelines LONTS (long-term administration of opioids for non-tumor pain). Schmerz 24(4), 309–312 (2010).

- Martell BA, O’Connor PG, Kerns RD et al. Systematic review: opioid treatment for chronic back pain: prevalence, efficacy, and association with addiction. Ann. Intern. Med. 146(2), 116–127 (2007).

- Manchikanti L, Singh V, Caraway DL, Benyamin RM. Breakthrough pain in chronic noncancer pain: fact, fiction, or abuse. Pain Physician 14(2), E103–E117 (2011).

- Lee M, Silverman SM, Hansen H, Patel VB, Manchikanti L. A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician 14(2), 145–161 (2011).

- Okie S. A flood of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. N. Engl. J. Med. 363(21), 1981–1985 (2010).

- Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Fan MY, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clin. J. Pain 26(1), 1–8 (2010).

- Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Fan MY, Devries A, Brennan Braden J, Martin BC. Risks for possible and probable opioid misuse among recipients of chronic opioid therapy in commercial and medicaid insurance plans: The TROUP Study. Pain 150(2), 332–339 (2010).

- Sullivan MD. Limiting the potential harms of high-dose opioid therapy: comment on ‘Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain’. Arch. Intern. Med. 171(7), 691–693 (2011).

- Katz MH. Long-term opioid treatment of nonmalignant pain: a believer loses his faith. Arch. Intern. Med. 170(16), 1422–1424 (2010).

- Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose: a cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 152(2), 85–92 (2010).

- Saunders KW, Dunn KM, Merrill JO et al. Relationship of opioid use and dosage levels to fractures in older chronic pain patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 25(4), 310–315 (2010).

- Walker JM, Farney RJ, Rhondeau SM et al. Chronic opioid use is a risk factor for the development of central sleep apnea and ataxic breathing. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 3(5), 455–461 (2007).

- Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA 299(1), 70–78 (2008).

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Electronic prescription monitoring. Policy Statement. Ann. Emerg. Med. 59(3), 241–242 (2012).

- Solanki DR, Koyyalagunta D, Shah RV, Silverman SM, Manchikanti L. Monitoring opioid adherence in chronic pain patients: assessment of risk of substance misuse. Pain Physician 14(2), E119–E131 (2011).

- Christo PJ, Manchikanti L, Ruan X et al. Urine drug testing in chronic pain. Pain Physician 14(2), 123–143 (2011).

- Manchikanti L, Malla Y, Wargo BW, Fellows B. Comparative evaluation of the accuracy of immunoassay with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) of urine drug testing (UDT) opioids and illicit drugs in chronic pain patients. Pain Physician 14(2), 175–187 (2011).

- Manchikanti L, Malla Y, Wargo BW, Fellows B. Comparative evaluation of the accuracy of benzodiazepine testing in chronic pain patients utilizing immunoassay with liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) of urine drug testing. Pain Physician 14(3), 259–270 (2011).

- McCarberg BH. A critical assessment of opioid treatment adherence using urine drug testing in chronic pain management. Postgrad. Med. 123(6), 124–131 (2011).

- Ling W, Mooney L, Hillhouse M. Prescription opioid abuse, pain and addiction: clinical issues and implications. Drug Alcohol Rev. 30(3), 300–305 (2011).

- Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL et al. Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA 300(22), 2613–2620 (2008).

- Toblin RL, Paulozzi LJ, Logan JE, Hall AJ, Kaplan JA. Mental illness and psychotropic drug use among prescription drug overdose deaths: a medical examiner chart review. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71(4), 491–496 (2010).

- Degenhardt L, Hall W. Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet 379(9810), 55–70 (2012).

- White AG, Birnbaum HG, Mareva MN et al. Direct costs of opioid abuse in an insured population in the United States. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 11(6), 469–479 (2005).

- Birnbaum HG, White AG, Reynolds JL et al. Estimated costs of prescription opioid analgesic abuse in the United States in 2001: a societal perspective. Clin. J. Pain 22(8), 667–676 (2006).

- Birnbaum HG, White AG, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, Roland CL. Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse in the United States. Pain Med. 12(4), 657–667 (2011).

- Hansen RN, Oster G, Edelsberg J, Woody GE, Sullivan SD. Economic costs of nonmedical use of prescription opioids. Clin. J. Pain 27(3), 194–202 (2011).

- Ghate SR, Haroutiunian S, Winslow R, McAdam-Marx C. Cost and comorbidities associated with opioid abuse in managed care and Medicaid patients in the United Stated: a comparison of two recently published studies. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 24(3), 251–258 (2010).

- CDC. Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids among Medicaid enrollees – Washington, 2004–2007. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 58(42), 1171–1175 (2009).

- White JA, Tao X, Talreja M, Tower J, Bernacki E. The effect of opioid use on workers’ compensation claim cost in the State of Michigan. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 54(8), 948–953 (2012).

- Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Fan MY, Braden JB, Devries A, Sullivan MD. An analysis of heavy utilizers of opioids for chronic noncancer pain in the TROUP study. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 40(2), 279–289 (2010).

- Katz N, Panas L, Kim M et al. Usefulness of prescription monitoring programs for surveillance–analysis of Schedule II opioid prescription data in Massachusetts, 1996–2006. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 19(2), 115–123 (2010).

- Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA 305(13), 1315–1321 (2011).

- Lanier WA. Prescription opioid overdose deaths – Utah, 2008–2009. Presented at: 59th Annual Epidemic Intelligence Service Conference. Atlanta, GA, USA, 19–23 April 2010.

- Volkow ND, McLellan TA, Cotto JH, Karithanom M, Weiss SR. Characteristics of opioid prescriptions in 2009. JAMA 305(13), 1299–1301 (2011).

- Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur. J. Pain 10(4), 287–333 (2006).

- Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA. Obamacare 2012: prognosis unclear for interventional pain management. Pain Physician 15(5), E629–E640 (2012).

- Fillingim RB, Doleys DM, Edwards RR, Lowery D. Clinical characteristics of chronic back pain as a function of gender and oral opioid use. Spine 28(2), 143–150 (2003).

- Webster BS, Verma SK, Gatchel RJ. Relationship between early opioid prescribing for acute occupational low back pain and disability duration, medical costs, subsequent surgery and late opioid use. Spine 32(19), 2127–2132 (2007).

- Mahmud MA, Webster BS, Courtney TK, Matz S, Tacci JA, Christiani DC. Clinical management and the duration of disability for work-related low back pain. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 42(12), 1178–1187 (2000).

- Franklin GM, Stover BD, Turner JA, Fulton-Kehoe D, Wickizer TM; Disability Risk Identification Study Cohort. Early opioid prescription and subsequent disability among workers with back injuries: the Disability Risk Identification Study Cohort. Spine 33(2), 199–204 (2008).

- Rhee Y, Taitel MS, Walker DR, Lau DT. Narcotic drug use among patients with lower back pain in employer health plans: a retrospective analysis of risk factors and health care services. Clin. Ther. 29(Suppl.), 2603–2612 (2007).

- Gross DP, Stephens B, Bhambhani Y, Haykowsky M, Bostick GP, Rashiq S. Opioid prescriptions in Canadian workers’ compensation claimants: prescription trends and associations between early prescription and future recovery. Spine 34(5), 525–531 (2009).

- Volinn E, Fargo JD, Fine PG. Opioid therapy for nonspecific low back pain and the outcome of chronic work loss. Pain 142(3), 194–201 (2009).

- Cifuentes M, Webster B, Genevay S, Pransky G. The course of opioid prescribing for a new episode of disabling low back pain: opioid features and dose escalation. Pain 151(1), 22–29 (2010).

- Webster BS, Cifuentes M, Verma S, Pransky G. Geographic variation in opioid prescribing for acute, work-related, low back pain and associated factors: a multilevel analysis. Am. J. Ind. Med. 52(2), 162–171 (2009).

- Franklin GM, Rahman EA, Turner JA, Daniell WE, Fulton-Kehoe D. Opioid use for chronic low back pain: a prospective, population-based study among injured workers in Washington state, 2002–2005. Clin. J. Pain 25(9), 743–751 (2009).

- Becker N, Sjøgren P, Bech P, Olsen AK, Eriksen J. Treatment outcome of chronic non-malignant pain patients managed in a Danish multidisciplinary pain centre compared to general practice: a randomised controlled trial. Pain 84(2–3), 203–211 (2000).

- Eriksen J, Sjøgren P, Bruera E, Ekholm O, Rasmussen NK. Critical issues on opioids in chronic noncancer pain: an epidemiological study. Pain 125(1–2), 172–179 (2006).

- Volkow ND, McLellan TA. Curtailing diversion and abuse of opioid analgesics without jeopardizing pain treatment. JAMA 305(13), 1346–1347 (2011).

- Paulozzi LJ, Stier DD. Prescription drug laws, drug overdoses, and drug sales in New York and Pennsylvania. J. Public Health Policy 31(4), 422–432 (2010).

- Paulozzi LJ, Kilbourne EM, Shah NG et al. A history of being prescribed controlled substances and risk of drug overdose death. Pain Med. 13(1), 87–95 (2012).

- Paulozzi LJ, Kilbourne EM, Desai HA. Prescription drug monitoring programs and death rates from drug overdose. Pain Med. 12(5), 747–754 (2011).

- Franklin GM, Mai J, Turner J, Sullivan M, Wickizer T, Fulton-Kehoe D. Bending the prescription opioid dosing and mortality curves: impact of the Washington State opioid dosing guideline. Am. J. Ind. Med. 55(4), 325–331 (2012).

Websites

- Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2011. United Nations, New York, NY, USA (2012). www.unodc.org/documents/southasia/reports/2011_INCB_ANNUAL_REPORT_english_PDF.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). World Drug Report 2010, Vienna, Austria: Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (2010). Report No. E.10XI.13. www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/WDR_2010/World_Drug_Report_2010_lo-res.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). World Drug Report 2011, Vienna, Austria: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2011). www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/WDR2011/World_Drug_Report_2011_ebook.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- CDC. Policy Impact: Prescription Painkiller Overdoses, November 2011. www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafety/pdf/PolicyImpact-PrescriptionPainkillerOD.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12–4713. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD, USA (2012). www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k11Results/NSDUHresults2011.htm (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- International Narcotics Control Board. Narcotic Drugs Technical Report: Estimated World Requirements for 2012 – Statistics for 2010. United Nations, New York, NY, USA (2011). www.incb.org/incb/en/narcotic-drugs/Technical_Reports/2011/narcotic-drugs-technical-report_2011.html (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2008. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD, USA (2009). www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus08.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- Warner M, Chen LH, Makuc DM, Anderson RN, Miniño AM. Drug poisoning deaths in the United States, 1980–2008. NCHS data brief, no. 81. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD, USA (2011). www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db81.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- SDI, Vector One®: National. www.sdihealth.com/vector_one/services.aspx (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- US Government Accountability Office: Report to Congressional Requesters. Prescription Pain Reliever Abuse, December 2011. www.gao.gov/assets/590/587301.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2012)

- Unintentional Drug Poisoning in the United States. CDC, July 2010. www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/pdf/poison-issue-brief.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- Ohio Department of Health. Epidemic of prescription drug overdose in Ohio (2010). www.healthyohioprogram.org/vipp/data/~/media/B36238B3B2C746308AA51232575613DD.ashx (Accessed 4 February 2012)

- Federation of State Medical Boards of the US. Model guidelines for the use of controlled substances for the treatment of pain: a policy document of the Federation of State Medical Boards of the United States, Inc. Dallas, TX, USA (1998). www.medsch.wisc.edu/painpolicy/domestic/model.htm (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- Letter to Janet Woodcock, MD, Director, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US FDA, from Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing RE Docket No. FDA-2011-D-0771, Draft Blueprint for Prescriber Education for Long-Acting/Extended Release Opioid Class-Wide Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies. 2 December 2011. www.rxreform.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/ARPO-Statement-on-FDA-Draft-Blueprint-112911.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- Methadone Mortality Working Group Drug Enforcement Administration, Office of Diversion Control, April 2007. www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drugs_concern/methadone/methadone_presentation0407_revised.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- Xu J, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2007. National Vital Statistics Reports. Volume 58 No. 19. National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD, USA (2010). www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_01.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- National Health Services, The National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse. Addiction to medicine. An investigation into the configuration and commissioning of treatment services to support those who develop problems with prescription-only or over-the-counter medicine. (2011). www.nta.nhs.uk/uploads/addictiontomedicinesmay2011a.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. Treatment Episodes Data Set (TEDS) Highlights. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services, Rockville, MD, USA (2005–2007). www.samhsa.gov/data/DASIS/TEDS2k7AWeb/TEDS2k7AWeb.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- Magellan Health Services. White paper: taking on prescription drug abuse through customized state solutions across the care continuum. www.oregon.gov/oha/pharmacy/DocumentsArticlesPublications/Customized%20State%20Solutions%20%E2%80%93%20Magellan%20Health%20Services.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- US Department of Justice, National Drug Intelligence Center. The Economic Impact of Illicit Drug Use on American Society (2011). www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44731/44731p.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- Baldasare A. The cost of prescription drug abuse: a literature review. Strategic Applications International. 6 January 2011. http://sai-dc.com/download/resources/20110106-cost-of-prescription-drug-abuse.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Drug diversion in the Medicaid Program. State strategies for reducing prescription drug diversion in Medicaid. January 2012. www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Fraud-Prevention/MedicaidIntegrityProgram/downloads/drugdiversion.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- Public law No: 109–60. H.R.1132 signed by President George W. Bush on 11 August 2005. www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-109publ60/pdf/PLAW-109publ60.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- U.S. Department of Justice, National Drug Intelligence Center. The Economic Impact of Illicit Drug Use on American Society. 2011. www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs44/44731/44731p.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

- Methadone Mortality Working Group Drug Enforcement Administration, Office of Diversion Control, April 2007. www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drugs_concern/methadone/methadone_presentation0407_revised.pdf (Accessed 4 February 2013)

Lessons learned in the abuse of pain-relief medication: a focus on healthcare costs