Abstract

Background

The introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy has resulted in improved survival and quality of life for individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). There is, as expected, a growing population of perinatally HIV-infected women who are, have been, or will become pregnant. We describe a large cohort of perinatally infected women, compare it with a similar age-matched behaviorally HIV-infected group, and examine factors affecting maternal and infant health.

Methods

We reviewed the records of 30 perinatally infected women who gave birth at two hospitals between January 2000 and December 2011. The comparison group comprised behaviorally infected women who delivered at these hospitals during the same period. The outcome measures were differences in CD4 counts and viral load between the cohorts, and comparisons of maternal morbidity, mortality, and mother-to-child HIV transmission.

Results

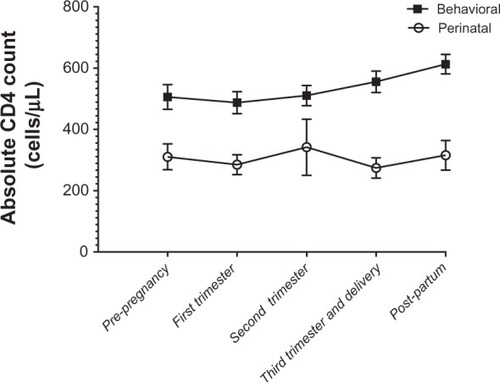

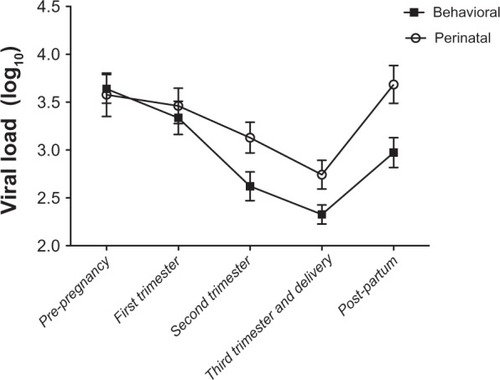

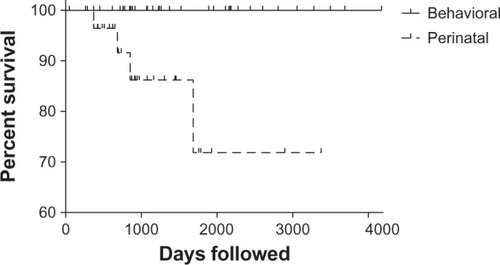

Median CD4 counts were significantly lower in the perinatal group before, during, and after pregnancy. The median viral load was significantly higher in the perinatal group. Interval prepregnancy to post partum viral load decline was also greater in the behavioral group. Viral load decreases in the perinatal population were not sustained in the post partum period, at which time viral load trended back to prepregnancy levels. There was one mother-to-child HIV transmission in a perinatally infected woman. Over an extended 4 years of follow-up, there were four deaths in the perinatal group and none in the behavioral group.

Conclusion

After delivery, the differences between perinatally and behaviorally infected mothers accentuate, with immunologic deterioration in the former group. The perinatal population may require novel management strategies to ensure outcomes comparable with those observed in the behavioral group.

Introduction

The introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy has resulted in dramatic increases in survival rates and improvement in quality of life for individuals who are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive, including those infected perinatally.Citation1 Aggressive diagnosis and treatment of pregnant HIV-infected women have led to near eradication of maternal-to-child HIV transmission in well resourced nations.Citation2 There are now only about 100–200 new cases per year of perinatally acquired HIV infection in the US,Citation3 and US and European Pediatric HIV programs are increasingly caring for a population comprising perinatally and behaviorally infected adolescents and young adults, rather than children. There is, as expected, a growing population of perinatally infected young women who are, have been, or are going to become pregnant, and many will have more than a single pregnancy. This rapidly growing group of women with lifelong HIV infection is unique. Most have had extensive exposure to successive antiretroviral regimens and their toxicities, may harbor resistant virus, and therefore may have limited treatment options. Just as importantly, they often suffer from numerous psychosocial stressors including depression, isolation and familial loss. Thus, this is a population that presents many challenges both from the medical and behavioral perspectives, and may require a different management approach to ensure results that are commensurate with those seen in pregnant women with behaviorally acquired HIV-infection.

There are limited published data on the course of pregnancy and maternal health outcomes in perinatally infected women living in well resourced settings. We recently reported our observations of a group of 11 young pregnant perinatally infected and 27 older behaviorally infected women followed in an urban pediatric and adult treatment center.Citation4 Here we expand our study to include a larger cohort of pregnant perinatally infected women, extend the length of the follow-up period, and limit the age of the behaviorally infected comparison group to 26 years. There is no population that can serve as a true control for our perinatally infected cohort. Nonetheless, the ability to analyze contemporaneous data for the two cohorts of pregnant women, one perinatally infected and the other behaviorally infected, of similar age and socioeconomic background, followed by the same medical centers, allows us to gain valuable insights into the problems faced by the perinatal group. Hopefully, this will advance knowledge to inform future management strategies and treatment guidelines.

Materials and methods

This study retrospectively reviewed all known perinatally HIV-infected women who gave birth at two large hospitals in the Bronx, NY, USA (an urban area of high HIV seroprevalence), between January 2000 and December 2011. The aged-matched comparison population comprised behaviorally infected women aged 16–24 years who delivered during the same period and received care at the same two hospitals. Terminations of pregnancy and miscarriages were excluded from the final analysis. If a woman became pregnant more than once, each pregnancy was considered as a separate event because it was assumed that psychosocial circumstances and HIV-specific parameters, such as age, disease status, drug availability, treatment, and adherence, varied with each pregnancy.

Data including patient demographics, laboratory results, and combination antiretroviral therapy regimens, and perinatal information was obtained by reviewing all prenatal, delivery, and post partum records. Maternal self-reporting of mental illness, domestic violence, and substance use based on standard obstetric assessment during labor and delivery was recorded. Women were classified by HIV disease severity using the Centers for Disease Control clinical staging system based on their CD4 counts and comorbidities at the time of pregnancy.

CD4 count and viral load were recorded, when available, for the year prior to conception, at each visit during pregnancy, and for the 9–12 months following delivery. All data for each time period, ie, before pregnancy, first, second, and third trimester, delivery, and post partum, were entered and averaged in their respective categories. Because only 30% of all the patients had complete sets of viral load and CD4 values for both the third trimester and delivery, and there was no statistically significant difference between those two time points, we averaged third trimester and delivery results and reported them as a single measurement. Viral loads were expressed and compared using the logarithmic scale (log10). Maternal combination antiretroviral therapy exposure to all drugs in pregnancy was recorded and classified as containing a protease inhibitor (PI), nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), or an integrase inhibitor. Mode of delivery was classified as normal vaginal, cesarean section secondary to emergent obstetric indications, cesarean section secondary to elective obstetric indications, and cesarean section secondary to HIV (viral load log10 > 3). Maternal charts were reviewed for all encounters during the study to record any pregnancy, post partum complications, infections, or readmissions. Infants were also followed for one year. They were considered uninfected if there was documentation of negative status by one year of age as assessed by required HIV nucleic acid polymerase chain reaction testing performed by the New York State Department of Health.

Patients who had a resistance test performed within one year of pregnancy were included in a genotype sensitivity score analysis. The genotype sensitivity score of the pregnancy regimen was calculated using the Stanford interpretation algorithm (http://sierra2.stanford.edu/sierra/servlet/JSierra). For each antiretroviral drug, patients with fully susceptible virus were assigned a sensitivity score of 1, and those with potential low-level, low-level, intermediate, and high-level resistance were assigned scores of 0.75, 0.50, 0.25, and 0, respectively. If ritonavir was used in conjunction with another protease inhibitor, it was assumed that ritonavir was used only as a pharmacologic booster, and hence it was not considered when calculating the genotype sensitivity score. Major mutations were recorded.

For the statistical analysis we included all datum points from all pregnancies. In addition to descriptive statistical tests, we applied mixed-effects linear models to incorporate both correlation of within-subject outcomes due to repeated measures and correlation between pregnancies within mothers. The dependent variables included but were not limited to log10 viral load, percent CD4, and absolute CD4 counts. The fixed effects included risk group, time, risk group-by-time interaction, and covariates.

Reported P values are two-sided and a value below 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Data were recorded in Microsoft Excel and analyzed and graphed using Minitab (State College, PA, USA), SAS (Cary, NC, USA), and GraphPad (La Jolla, CA, USA) software. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at each of the two participating hospitals.

Results

There were 40 pregnancies in 32 perinatally infected women. Three pregnancies were excluded because of nonviable infants, leaving 37 pregnancies in 30 women. Seven women had two pregnancies each; no woman in either group had more than two pregnancies. For the behaviorally infected group, 45 pregnancies in 39 age-matched women were available for review. Four pregnancies were excluded because of nonviable births; one was excluded because of incomplete information, leaving 40 pregnancies in 35 behaviorally infected women (five women with two pregnancies). No women in either the perinatal or behavioral group were lost to follow-up.

The mean age of the behaviorally and perinatally infected women was 21.4 years and 20.9 years, respectively (P = 0.42, t-test). There was a small difference in self-reported ethnic background between the two groups (more Hispanic women in the perinatally infected group), and a higher percentage of African-Americans in the behaviorally infected group (). All the women resided in New York City and were enrolled in Medicaid at the time of delivery. Women in the perinatally infected group were more likely to be primigravid. They were also more likely to have a cesarean section because of a high viral load and/or non-HIV related obstetric indications (P = 0.03, Chi-square, ).

Table 1 Characteristics of women who were behaviorally or perinatally infected with human immunodeficiency virus

There was one case of mother-to-child HIV transmission in a nonbreastfeeding, perinatally infected woman. Her pregnancy treatment regimen consisted of a ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor and triple NRTI, with a variable viral load response. Because at term her viral load log10 copies/mL had dropped from 4 and 3.8 in the first and second trimester to 2.0, she delivered vaginally. The infant’s HIV RNA polymerase chain reaction was negative at birth and turned positive at 39 days of life.

Due to concerns about extensive HIV drug resistance in the mothers, seven newborns in the perinatal group received a three-drug prophylaxis regimen and one received a two-drug regimen. All other infants in the study, including the one later found to be HIV-infected, were prescribed a standard 42-day prophylactic course of zidovudine.

The perinatally infected women were more likely to deliver at an earlier gestational age and their newborns had a lower average birth weight (P = 0.03, Mann-Whitney test, ).

More of the perinatally infected women were monitored with regard to CD4 levels and viral load in the period before pregnancy. This was expected, because most of these women had longstanding relationships with their care centers, whereas approximately 20% (7/35) of the behaviorally infected women were newly diagnosed with HIV during their pregnancy. Third trimester and/or delivery viral load results were available for all women in the study. Post partum data were available on 95% of the behaviorally infected and 97% of the perinatally infected women. Maternal-to-child HIV transmission information was available for 100% of the newborns. There was no significant difference in type of combination antiretroviral therapy prescribed during pregnancy in the two groups, except for protease inhibitor use, which was more common in the perinatally infected group (P = 0.03, Fisher’s Exact test).

CD4 and viral load comparisons are shown in . There was a statistically significant difference in CD4 parameters between the two groups across all time points (). There was no difference in viral load between the two groups in the prepregnancy period or the first trimester, but a statistically significant difference was noted in the second, third trimester/delivery, and post partum periods (). There was also a statistically significant difference in the interval prepregnancy to post partum viral load change between the behaviorally infected and the perinatally infected groups, with the behavioral group experiencing a greater drop. More importantly, the viral load decline achieved in the perinatal group was not sustained in the post partum period, when viral load trended back to prepregnancy levels (). This did not occur in the behavioral group.

Figure 1 Viral load across time points in women behaviorally and perinatally infected with the human immunodeficiency virus.

Figure 2 CD4 counts across time points in women behaviorally and perinatally infected with the human immunodeficiency virus.

Table 2 CD4 and viral load comparisons between women who were behaviorally or perinatally infected with human immunodeficiency virus

The results of the mixed-effect models showed that when we adjusted for Centers for Disease Control disease category, the viral load differences seen at all three time points, ie, second trimester, third trimester/delivery, and post partum were all maintained (P = 0.02, P = 0.02, and P = 0.005, respectively). In contrast, when adjusting for birth weight, ethnicity/race category, protease inhibitor use, and gestational age, the previously found statistically significant difference in viral load between the perinatally and behaviorally infected groups in the second and third trimester/delivery periods was no longer observed. However, the difference observed in the post partum period remained statistically significant (P = 0.01). Of note, the difference seen in viral load in the post partum period persisted, whether analyzed by pregnancy or by woman to remove the bias of multiple pregnancies.

Genotypes were not available for all women around the time of pregnancy and were only available for review for 36 women, ie, 13 in the behavioral group and 23 in the perinatal group. Although mutations were more frequent in the perinatal group and genotype sensitivity scores were lower in the perinatal group compared with the behavioral group (mean 2.42 versus 3), they were not significantly different.

In our combined population of 65 women, there was one case of documented HIV disease progression during pregnancy (disseminated cryptococcosis), which occurred in a woman infected perinatally. Mental health diagnosis, primarily depression, was equally common in both groups (approximately 40%). On the other hand, self-reporting of substance abuse was infrequent (two women infected behaviorally and only one woman infected perinatally). Apart from differences in cesarean section rates, pregnancy-related complications (ie, gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia, and cesarean section wound infection) were few and comparable in the two groups. Clinical genital herpes simplex and history of abnormal Papanicolaou smears were equally common in the two groups (15 and 8/35 behaviorally infected, 19 and 6/30 perinatally infected, respectively). The prevalence of viral hepatitis B and C was comparable, with two women having hepatitis B in the behavioral group and one woman having hepatitis B in the perinatal group (P = 1.00). There were two women with hepatitis C in the perinatal group (P = 0.23). However, there was one case of perinatal transmission of viral hepatitis B in a mother-infant pair despite adequate prevention strategies, including hepatitis B immunoglobulin and viral hepatitis B vaccine. The mother was not on antivirals with activity against hepatitis B and had positive hepatitis B e antigen.

We have complete viral load and CD4 data extending to one-year post partum for both groups. In addition, 10 perinatally infected and 21 behaviorally infected women have been followed for up to four or more years. In that extended follow-up period, there was a striking disproportion in mortality between the two groups, with four deaths (13%) in the perinatal group and none in the behavioral group. The deaths occurred at approximately one, two, three and four years post partum, all from complications related to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS, ). Of those four women, three had CD4 < 50 cells/μL and viral load log10 > 4.7 copies/mL at one year after delivery.

Figure 3 Simple survival curve with censored subjects denoted.

Discussion

We describe the largest cohort to date of pregnant adolescents and young women infected with HIV perinatally delivering live newborns in the US. We also compare their one-year prepregnancy, pregnancy, and one-year post partum clinical, immunologic, and virologic parameters with those of an age-matched behaviorally infected group. We found that, in general, perinatally infected women had poorer virologic and immunologic parameters before and during pregnancy, with these differences observed especially in the post partum period. Although half of the perinatal cohort achieved viral load log10 < 2.6 copies/mL by the end of pregnancy, virologic suppression was not sustained post partum in the majority. Of the four women who died, three had CD4 counts of <50 cells/μL and viral load log10 > 4.7 copies/mL at one year after delivery. Of great concern, these three women were documented as having stopped taking antiretroviral medication on their own initiative shortly after giving birth, despite the availability of comprehensive integrative medical and psychosocial support systems. Our findings raise the possibility that perinatally infected women are at higher risk for disease progression and death post partum. With genotype sensitivity scores similar to their age-matched, behavioral counterparts, it seems that there are effective treatment options and that virologic control is achievable for these women. Therefore, the observed disease progression may not be related to treatment failure per se but rather to circumstances leading to self-discontinuation of therapy and barriers to accessing available resources. More research is needed to explore potentially relevant psychologic and psychosocial issues, such as depression, post-traumatic stress, and social marginalization. We propose that there is a need for novel approaches to the care of this uniquely vulnerable population.

The epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in the US has evolved over time, with a significant proportion of new infections occurring in heterosexual women of childbearing age. This has implications for pregnancy, maternal-to-child HIV transmission, and women’s overall health.Citation5,Citation6 Recent advances and widespread use of combination antiretroviral therapy have led to an overall delay in the progression of HIV disease and a consequent increase in life expectancy, with improved quality of life.Citation1 These advances have had a direct effect on pregnancy rates among HIV-infected women, particularly in the younger age groups.Citation7,Citation8 Worldwide, women newly diagnosed with HIV infection during pregnancy are now more likely to be started on and benefit from combination antiretroviral therapy, but usage of combination antiretroviral therapy in the developing world still lags behind the US, Western Europe, and other industrialized countries. As expected, in well resourced settings, pregnant HIV-infected women tend to have higher CD4 counts and lower viral load,Citation9 a trend that was confirmed in our behaviorally infected cohort. However, the perinatal population we describe, which is reaching significant numbers, may deviate from these patterns, especially with respect to risk of disease progression and death.

Large comprehensive world studies of maternal morbidity and mortality report that in countries with high HIV infection prevalence, HIV/AIDS may decrease pregnancy rates but increases the risk of obstetric complications, and is the leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths. In addition, HIV-related anemia and tuberculosis may be aggravated by pregnancy. However, the epidemiologic evidence does not support the hypothesis that relative immune suppression in pregnancy exacerbates HIV disease itself.Citation10–Citation12 Our data corroborate these findings, because the immunologic and virologic parameters during pregnancy remained stable in both groups, with improved viral control towards the end of pregnancy and near delivery. We did not observe indicators of HIV progression during pregnancy in either of our two groups, except for the one patient with newly diagnosed cryptococcosis in the perinatal group. Because the overall impact of pregnancy on HIV progression appears to be limited, a significant proportion of our efforts should be devoted to the post partum period, when multiple factors appear to result in poor adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy, and mental health problems become increasingly present.Citation13–Citation15

By definition, perinatally infected women have lifelong disease, with the potential for varying degrees of end-organ compromise. In addition, most have had exposure to multiple antiretroviral regimens, experienced treatment failure, and have likely accumulated and archived HIV drug resistance. All of these factors have a bearing on maternal treatment needs and negatively impact on the goal of achieving full viral suppression during pregnancy and at delivery. It is not surprising to find that there were nine cesarean sections secondary to viral load log10 copies/mL > 3 in our perinatal cohort, contrasting with only three in the behavioral group. Nonetheless, our data demonstrate that viral suppression is feasible, even in the highly experienced group, with 19/37 (51%) achieving a viral load log10 < 2.6 at third trimester/delivery, suggesting that the perinatal population has viable treatment options. Furthermore, it suggests that the number of elective cesarean sections in the perinatal group may be reducible. The failure to sustain virologic control into the postpartum period in the perinatal group is of great concern, especially because it appears to lead to deterioration in maternal health as defined by viral load and CD4.

The behaviorally infected group was more heterogeneous, including a considerable proportion of women newly diagnosed as HIV-infected (approximately 20%). Of note, this cohort did not include mothers identified peripartum through expedited HIV testing or by the newborn screen, which in New York State always includes HIV antibody. It is interesting to compare our behavioral group with larger US cohorts with respect to new diagnosis. Only 53% of 1090 HIV-infected pregnant women aged 13–21 years reported to the Centers for Disease Control from 28 states with perinatal HIV registry were aware of their HIV status before pregnancy.Citation16 The subgroup of women newly infected and/or diagnosed during pregnancy warrants further study but is beyond the scope of this report.

Multicenter studies of HIV-infected pregnant women in the pre-highly active antiretroviral therapy era describe self-reported hard drug use during pregnancy to be as high as 40%.Citation17 Exposure to drugs may increase maternal-to-child HIV transmission, even in the presence of highly active antiretroviral therapy, via placental barrier disruption, preterm birth, and increasing viral load. There is also the association of drug use with poor adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy and medical care.Citation18 We were surprised by the low prevalence of drug use in both cohorts (2.7% in the perinatal group and 5% in the behavioral group). This may be a reflection of the young age of our study population, and overall decreased drug use in pregnant women.

In a 2003 study exploring post-delivery progression of HIV disease in behaviorally infected women,Citation19 and a 2009 follow-up of a similar population,Citation20 the authors describe earlier trends when women tended not to continue antiretroviral therapy after pregnancy (currently it is recommended that combination antiretroviral therapy be continued post partum). In those studies, viral load decreased during pregnancy and rose slightly post partum. This was observed in women both on and off treatment, and suggested an effect independent of combination antiretroviral therapy. The authors attributed these viral load fluctuations to multiple biologic (dilutional, estrogen/progesterone effects, increased immune activation) as well as behavioral factors (decreased adherence in the context of newborn care and disappearance of the incentive to prevent maternal-to-child HIV transmission). More recently, the cytokine milieu during pregnancy and after delivery has been better described, with an increase in interleukin-10 during pregnancy (downregulating viral replication), and an increase in interleukin-6 post partum (upregulating viral replication).Citation21

Adherence during pregnancy and post partum has been explored in detail in recent studies, showing two distinct patterns: one, in the prepartum and peripartum periods, where the focus is on preservation and maintenance of maternal health and prevention of maternal-to-child HIV transmission; the second, in the post partum period, when the mother has the new demands of child care, and may be at risk for post natal depression and be more likely to revert to prepregnancy behavioral patterns. The life circumstances of these women invariably define their motivation towards adherence. The factors found to be most commonly associated with nonadherence prepartum were advanced HIV disease, high viral load, more health-related symptoms, and alcohol and tobacco use, whereas post-delivery, they were ethnicity, more health-related symptoms, and enrollment at a WITS clinical site.Citation13,Citation14 In addition, having post natal depression correlates with substance abuse during pregnancy and a past history of mental health illness. Those with CD4+ < 200 cells/μL and nonadherence were more likely to have post natal depression.Citation15 However, these studies did not include information on the perinatal population.

The concerning and crucial finding in our report is that, after delivery, the differences between perinatally and behaviorally infected young mothers accentuate, with progressive worsening of immunologic health in the former group. The trend we observed in the perinatal cohort, particularly because we controlled for CD4 count effect on viral load across the different time points, strongly supports the notion that the post partum period appears to be the most vulnerable time for these young women.

Pregnant perinatally HIV-infected women and adolescents face multiple obstacles to a good outcome. There is a need for a more intense approach to ensure better lifetime access to care for them, their partners, and their offspring. The medical model alone may not be sufficient to meet the complex demands of this population. A network of community programs providing housing, education, and mental health services specifically designed for these families should be developed. In addition, we propose that these patients receive care in designated multidisciplinary post partum mother-child clinics. We hope that this study and the insights gained by comparing perinatally infected mothers with their behaviorally infected peers will lead to better intervention and treatment strategies.

Acknowledgments

AW and JA are funded in part by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development International and Domestic Pediatric and Maternal HIV Studies Coordinating Center.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- RayMLoganRSterneJAThe effect of combined antiretroviral therapy on the overall mortality of HIV-infected individualsAIDS20102412313719770621

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionEpidemiology of HIV/AIDS – United States, 1981–2005MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep20065558959216741494

- Centers for Disease Control and PreventionAchievements in public health. Reduction in perinatal transmission of HIV infection – United States, 1985–2005MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep20065559259716741495

- PhillipsUKRosenbergMGDobroszyckiJPregnancy in women with perinatally acquired HIV-infection: outcomes and challengesAIDS Care2011231076108221562997

- AhdiehLPregnancy and infection with human immunodeficiency virusClin Obstet Gynecol20014415416611344985

- ClarkRADumestreJWomen and human immunodeficiency virus: unique management issuesAm J Med Sci2004328172515254438

- BlairJMHansonDLJonesJLDworkinMSTrends in pregnancy rates among women with human immunodeficiency virusObstet Gynecol200410366366815051556

- TaiJHUdojiMABarkanicGPregnancy and HIV disease progression during the era of highly active antiretroviral therapyJ Infect Dis20071961044105217763327

- MinkoffHHershowRWattsDHThe relationship of pregnancy to human immunodeficiency virus disease progressionAm J Obstet Gynecol200318955255914520233

- GrayGEMcIntyreJAEffect of HIV on womenAIDS Read20061636536816874916

- RonsmansCGrahamWJMaternal mortality: who, when, where, and whyLancet20063681189120017011946

- GrayGEMcIntyreJAHIV and pregnancyBMJ200733495095317478849

- MellinsCAChuCMaleeKAdherence to antiretroviral treatment among pregnant and postpartum HIV-infected womenAIDS Care20082095896818608073

- BardeguezADLindseyJCShannonMAdherence to antiretrovirals among US women during and after pregnancyJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr20084840841718614923

- KapetanovicSChristensenSKarimRCorrelates of perinatal depression in HIV-infected womenAIDS Patient Care and STDs20092310110819196032

- KoenigLJEspinozaLHodgeKRuffoNYoung, seropositive, and pregnant: epidemiologic and psychosocial perspectives on pregnant adolescents with human immunodeficiency virus infectionAm J Obstet Gynecol2007197S123S13117825643

- ThorpeLEFrederickMPittJEffect of hard-drug use on CD4 cell percentage, HIV RNA level, and progression to AIDS-defining class C events among HIV-infected womenJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr2004371423143015483472

- Van DykeRBMother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in the era prior to the availability of combination antiretroviral therapy: the role of drugs of abuseLife Sci20118892292521439978

- WattsDHLambertJStiehmERProgression of HIV disease among women following deliveryJ Acquir Immune Defic Syndr20033358559312902802

- WattsDHLuMThompsonBTreatment interruption after pregnancy: effects on disease progression and laboratory findingsInfect Dis Obstet Gynecol2009200945671719893751

- El BeitunePDuarteGQuintanaSMFigueiro-FilhoEAHIV-1: maternal prognosisRev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo200459253115029282