Abstract

Objective

Longitudinal studies on headaches often focus on the identification of risk factors for headache occurrence or “chronification”. This study in particular examines psychological variables as potential predictors of headache remission in children and adolescents.

Methods

Data on biological, social, and psychological variables were gathered by questionnaire as part of a large population-based study (N=5,474). Children aged 9 to 15 years who suffered from weekly headaches were selected for this study sample, N=509. A logistic regression analysis was conducted with remission as the dependent variable. In the first step sex, age, headache type, and parental headache history were entered as the control variables as some data already existed showing their predictive power. Psychological factors (dysfunctional coping strategies, internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, anxiety sensitivity, somatosensory amplification) were entered in the second step to evaluate their additional predictive value.

Results

Highly dysfunctional coping strategies reduced the relative probability of headache remission. All other selected psychological variables reached no significance, ie, did not contribute additionally to the explanation of variance of the basic model containing sex and headache type. Surprisingly, parental headache and age were not predictive. The model explained only a small proportion of the variance regarding headache remission (R2=0.09 [Nagelkerke]).

Conclusion

Successful coping with stress in general contributed to remission of pediatric headache after 2 years in children aged between 9 and 15 years. Psychological characteristics in general had only small predictive value. The issue of remission definitely needs more scientific attention in empirical studies.

Introduction

Biopsychosocial pain model

Biological, psychological, and social factors play an important role in the development and perpetuation of pain.Citation1,Citation2 The significance of psychosocial factors was demonstrated in several studies.Citation3–Citation5 Besides biological (hereditary) factors, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral variables play an important role in explaining the occurrence of pediatric headache.Citation2,Citation6,Citation7 A 2012 study based on the same original dataset found a correlation between internalizing symptoms, anxiety sensitivity, self-acceptance, and somatosensory amplification (SSA) with pediatric headache.Citation3

Headache remission

Only very few studies dealing with predictors of headache remission were found in the literature search. One longitudinal study tried to identify biological predictors of migraine remission with onset in childhood or adolescence.Citation8 No significant predictors emerged in this clinical trial on 137 patients aged 3 to 17 years. A population-based study with 1,134 adult participants found “being married” and “diagnosed with diabetes” as positive predictors for the remission of daily headache which was a quite unexpected finding.Citation9

An examination of psychological factors as potential predictors for headache remission in children and adolescents so far had not been undertaken. Our prospective study examined whether selected psychological variables can explain additional variance regarding remission above certain control variables, for which some evidence had already been found regarding a remission of weekly headache in children and adolescents.

Control variables

Sex

There are sex differences regarding the prevalence as well as the risk factors for the incidence of headache.Citation10–Citation12 Female sex is a risk factor for the chronification of headache.Citation13 A higher persistence of headache in girls versus boys was found in a population-based study with 2,025 participating children.Citation14 Thus, a higher remission rate for boys compared to girls was expected.

Age

Increasing age of children is associated with an increase in headache prevalence.Citation10,Citation15 No studies addressing the possible association of age and remission of pediatric headache were found. We decided to include age into the model as an exploratory control variable.

Types of headache

Different predictors of incidence and prognosis were found for migraine and tension type headache (TTH).Citation16,Citation17 In an 8-year follow-up on a clinical trial including 100 children aged 4 to 18 years, Guidetti and Galli found a higher probability for the remission of TTH than for migraine.Citation18 Another longitudinal study with a 20-year follow-up found the same results in a sample of 60 children: remission was observed in only 19% of the patients with migraine compared to a remission rate of 53% for TTH.Citation19 In this study, a higher remission rate was expected for TTH compared to migraine.

Parental headaches

Parental headache can have an effect on the child on a biological as well as on a social level. On the one hand, serving as a role model, parents influence their child’s headache through the way they react to their own headache.Citation20 On the other hand, a distinct genetic influence in headaches has been shown.Citation21

Children whose parents suffer from headaches, have a higher probability to develop headaches themselves.Citation3,Citation22,Citation23 A longitudinal study on a population-based sample of 55 adolescents revealed a lower remission rate of migraine, if an immediate family member also suffers from migraine.Citation24 Thus, a negative correlation between parental headache and the remission of pediatric headache was to be expected.

Psychological predictors

Stress coping

Coping can be understood as the cognitive and behavioral effort to resolve a stressful situation.Citation25,Citation26 A connection between stress and pain exists, and is moderated by the way people cope with and react to pain.Citation27 Dysfunctional coping can contribute to the persistence of pain, as children are not able to reduce the negative impact of stress on their pain experience.Citation4,Citation28 Passive and avoiding coping strategies can be seen as dysfunctional and are expected to reduce the probability of headache remission.

Internalizing symptoms

Following the definition of Achenbach,Citation29 internalizing symptoms primarily include anxiety and depressive symptoms. A rather strong association between internalizing symptoms and pediatric headache was found in various studies.Citation3,Citation16 A higher level of internalizing symptoms was assumed to be associated with a lower chance for remission.

Externalizing symptoms

Externalizing symptoms in children, including aggressive behavior, anger, and hyperactivity, are correlated with headache.Citation3,Citation29 A connection between externalizing symptoms and the incidenceCitation30 and prevalenceCitation3 of pediatric headache has already been demonstrated in quite a few studies. We predicted a lower chance for remission in children with a higher level of externalizing symptoms.

Anxiety sensitivity

Anxiety sensitivity is a theoretical construct describing the fear of sensations associated with anxiety as symptoms of sympathetic activation are interpreted as dangerous and harmful.Citation31 They are experienced as aversive and induce anxiety.Citation32 A positive correlation between anxiety sensitivity and the incidence of headache has been shown in several studies.Citation33–Citation35 A possible connection between anxiety sensitivity and remission of headache seemed possible and was therefore examined.

SSA

SSA is a neighboring construct described as a tendency to experience somatic sensations as being particularly strong and disturbing.Citation36 Earlier studies mainly examined the connection between SSA and chronic pain in adults.Citation37,Citation38 A connection between SSA and the prevalence of headache in children seems to exist.Citation3 Our study aims at examining its contribution to headache remission for the first time.

Methods

Study design and sample

This study is part of the project “Children, adolescents and headache” conducted at the University of Göttingen, Germany. For this epidemiological longitudinal study, a total of 8,800 families having at least one child aged between 7 and 14 years, were randomly chosen from the public registries. Starting in the year 2003, these families received four yearly questionnaires addressed to the children as well as to the parents. The participants were asked to answer questions concerning their headaches, other pain, pain-related behaviors, and various psychosocial factors and conditions. The study design was approved by the ethical commission of the German Society for Psychology. Parents and children were fully informed about the research issues and study procedures. They were free to take part in the study and implied consent by sending in the questionnaires by mail. A more detailed description of the study design can be found in the article by Kröner-Herwig et al.Citation39

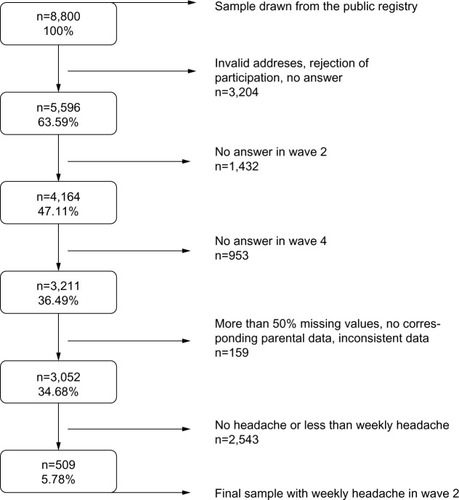

Only children (at least 9 years old) having completed their own questionnaire and with a matching parental questionnaire available were included. From this original dataset, a subset of the children suffering from weekly headache in wave two was selected. Cases with incomplete or inconsistent data were excluded (). The selected sample consisted of N=509 children; 61.5% female and 38.5% male. The mean age was M=12.0 years (standard deviation =1.1 years). The youngest child in wave 2 was 9 years old and the oldest was 15 years old. The sample size can vary in different analyses due to missing values in the variables of interest.

Operationalization of the dependent variable “headache”

The participating children were asked whether they had ever experienced headaches during the last 6 months. If they had, information regarding frequency, intensity, duration, and accompanying symptoms was assessed. The questionnaire was designed based on systematics of the second edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-II; IHS, 2004). It allowed a differentiation between migraine and TTH.Citation40

The 505 children having had at least one headache per week in wave two (6-month reference period) constituted the sample of “recurrent headache” examined for remission in wave 4 (2 years later). Remission was defined by the response “no headaches” or “less than once per month” (in wave 4). Otherwise the category “no remission” was attributed.

Operationalization of the predictors

Control variables

The data from the parental questionnaire (wave 1) were used to determine sex and age of the children. Headache type of the children was operationalized following the criteria of the ICHD-II.Citation41 Only migraine and TTH were differentiated leaving a category of “uncategorizable headache”, not fulfilling one or more criteria for migraine or TTH.

Parental headache was defined as a binary variable with the categories “at least weekly headache” and “less than weekly headache”. Data from the parental self-report questionnaire were used where parents had been asked about their headache frequency on a 4-point scale ranging from “no headache” to “at least weekly headache”.

Psychological variables: dysfunctional coping, internalizing, externalizing, anxiety sensitivity, and SSA

A limited number of items were taken from the the original validated psychometric tests (eg, Stresscoping test) because it was not practical to include the complete tests, and used for the assessment of these trait variables. Instead, a subsample of items were extracted from tests based on their item test correlation. Good to satisfying homogeneity of the shortened scales was found.Citation3 In a subsample of 250 children, high correlations of the shortened and the complete versions of the different scales (0.74≤r≤0.96) were demonstrated.Citation23

Dysfunctional coping was defined as a high score on the “habitual negative coping style” scale consisting of five items from the “Stressverarbeitungsfragebogen” (stress coping questionnaire).Citation42 Two items referred to aggression and one item each to passive avoidance, continued mental preoccupation, and resignation. The internal consistency of the shortened scale reached an α=0.76.Citation3

Information on internalizing and externalizing symptoms was collected using items from the Youth Self Report.Citation43 Eight items referring to anxiety/depression were selected from the sub-scale for internalizing symptoms. Six items referring to hyperactivity and aggressive behavior were taken from the sub-scale for externalizing disorders. The original 3-point scale of the items was transformed into a 5-point scale to guarantee better comparability with the other items of the questionnaire. With a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.9 for internalizing and 0.8 for externalizing symptoms, the scales showed a high internal consistency.Citation3

Five items selected from the Anxiety Sensitivity IndexCitation44 were used to assess the anxiety sensitivity of the children (α=0.7).Citation3 SSA was assessed using four items from the Somatosensory Amplification ScaleCitation45 asking the children about their personal impairment caused by unpleasant somatic sensations. However, the internal consistency of this scale was not fully satisfactory (α=0.6).Citation3

Statistical analysis

The main analysis consisted of a multiple logistic regression with “remission” as the dependent variable. Following Hosmer and Lemeshow,Citation46 at least ten subjects per parameter of the regression model are required in each category of the dependent variable. In the present sample, 109 subjects belonged to the category “remission”, 368 children did not show headache remission in wave 4. Consequently, a maximum of nine predictors could be included in the analysis. According to the theoretical reflections presented earlier, the following predictors were included: the four control variables sex, age, headache type, and parental headache were included in a first block, and the five psychological predictors anxiety sensitivity, SSA, dysfunctional coping, internalizing, and externalizing symptoms in a second one. Medication (preventive/abortive) was not used in the regression analysis, since it did not correlate significantly with the dependent variable (all P<0.20). Being a partly exploratory analysis, a stepwise (backward) procedure was used as recommended by Field.Citation47

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The significance threshold was set at P=0.05 for all analyses.

Results

Descriptive data

In the original sample in wave 2 (n=4,164; ) 19.8% were suffering from at least weekly headache in the past 6 months. More girls were suffering from headaches (23.8%) than boys (15.5%). TTH occurred in 7.8% of the subjects, migraine in 4.2% and non-categorizable headache was found in 7.8% ().

Table 1 Prevalence and remission rates depending on sex and headache type (%)

At the wave 4 assessment time-point, remission had occurred in 109 children equating to a remission rate of 23.9%. The remission rate was higher in boys (31.8%) than in girls (17.3%). Remission rates were lowest for migraine (13.1%), higher for TTH (21.2%), and highest for non-categorizable headache (). The mean values of the psychological variables were found in the low and middle range of the 5-point rating scales (1.53≤M≤2.4; ).

Table 2 Psychological predictors: descriptive statistics

Results of the logistic regression

The regression model explained 9% of the observed variance in the variable remission (Nagelkerke =0.09; ). Sex was a significant predictor of headache remission. The probability of remission was twice as high for boys than girls (odds ratio [OR] =2.18; P=0.001). Headache type also predicted headache remission. A remission was approximately 1.8 times less probable for TTH (OR =0.6; P=0.02) and approximately 2.6 times less probable for migraine compared to non-categorizable headache (). Age and parental headache were not significant predictors of headache remission and thus not included in the model.

Table 3 Logistic regression model with the included predictors (P≤0.05)

Of the five psychological predictors that were considered, only dysfunctional coping contributed to the prediction of headache remission (OR =0.8; P=0.04). A reduction by 1 point on the scale for negative habitual coping styles was associated with a 1.3 times higher probability for headache remission ().

All predictors were analyzed for multi-collinearity using the variance inflation factors. All variance inflation factors showed values smaller than 10. Following Field,Citation47 multi-collinearity was no problem in this analysis. The highest correlation between two predictors was found between negative habitual coping style and internalizing symptoms, r=0.7; P<0.01. All other correlations were smaller than r=0.50 ().

Table 4 Intercorrelations of all predictors and control variables

Discussion

Key results and interpretation

As expected, a significant association between the remission of pediatric headache and the control variables sex and headache type was confirmed. Male sex was a positive predictor of headache remission, ie, boys tended to show more headache remission than girls. The higher probability of remission in boys compared to girls matches the findings of Laurell et al.Citation48 Additionally, incidence and prevalence rates are higher in girls than in boys.Citation10–Citation12 The unfavorable prognosis for migraine compared to TTH and other types of headache also matches the findings in other studies.Citation18,Citation19 In general, headache is a bigger problem in girls than in boys. Remission is less probable for migraine as compared to TTH. A headache syndrome not fulfilling the criteria of migraine nor TTH had the best chances for remission in this study.

Against all expectations, no connection between age and parental headache with headache remission was found. The observation of Monastero et alCitation24 that a lower probability of migraine remission is associated with having a parent who is also suffering from headaches were not confirmed by our data. A familial influence on remission was neither seen in tension type nor in non-catagorizable headache. A correlation between increasing age and increasing prevalenceCitation10,Citation15 and a lower success rate of therapeutic interventionCitation49 had been shown, but no correlation with headache remission could be demonstrated in this study.

While none of the other considered psychological variables (internalizing and externalizing symptoms, anxiety sensitivity, and SSA) contributed significantly to the prediction of headache remission, dysfunctional coping with stress was identified as a predictor. The less dysfunctional coping strategies children reported at the assessment time, the more probable was a remission of their headache. This regression model was able to explain 9% of the variance of the dependent variable “remission”, R2=0.09 (Nagelkerke) compared to 8% explained by the model containing only the control variables.

Coping with stress is the only psychological predictor of headache remission that could be confirmed by this study. If stress cannot be resolved in an adequate way and a negative coping style is frequently used, the probability of headache remission is significantly reduced. Inversely, the use of adequate coping strategies should increase the probability of headache remission. This finding supports the ideas of Houle and Nash expressed in their reviewCitation50 of a close connection between stress and headache. They particularly consider stress as a main factor for the chronification of headache. These findings point to the important role of relaxation techniques and teaching of coping strategies in the treatment of headaches, which have already been integrated as part of different therapeutic programs aiming at headache improvement.Citation51 A meta-analysis conducted by Trautmann et al found that relaxation techniques were used in 27% of the included studies.Citation52

Limitations

The regression model presented in this study only explains a rather small part of the variance observed regarding headache remission. Thus, the psychological predictors having been measured 2 years before the critical assessment period of remission did not have a large impact on this procedural feature of headache. It must be assumed that a lot of factors not considered in this study might also play an important role. Headache remission seems to be a phenomenon influenced by a complex combination of biological, social, and psychological factors, but methodological considerations prohibited the inclusion of more possible predictors.

The final sample consisting of 509 children is relatively small for two reasons: we chose a relatively strict criterion for remission. To ensure that headache affection at baseline was of clinical significance, only children with at least weekly episodes were included, and only a less than monthly headache was allowed at the second assessment. The second reason relates to the 2-year instead of 1-year interval regarding the assessment of remission, which increases the general dropout rate in the long term compared to a 1-year period. Due to the size of the sample, differential analysis regarding sex or headache type did not appear appropriate on a statistical level. Still, the predictors (or their impact) for pediatric headache remission might differ depending on sex and headache type.

A possible methodological problem arises from the use of retrospective questionnaires asking about headache experiences during the last 6 months. A study comparing headache diaries and questionnaires showed that children tend to overestimate the intensity and duration of headache in retrospective questionnaires.Citation53 The retrospective assessment of headaches may have resulted in distorted prevalenceCitation14 and remission rates. However, the use of a binary-dependent variable should have reduced the error induced variance. An assessment using diaries instead of questionnaires as recommended by Van den Brink et al,Citation53 would have demanded a half year of self-monitoring in each of the two study periods, which without doubt would have reduced the respondents to nearly nil, given that no bonus for the participants could be offered.

The different predictors had been tested for multi-collinearity before conducting the logistic regression. Even though the values of the variance inflation factor did not indicate a multi-collinearity problem following the criteria of Field,Citation47 the relatively high correlation between the two predictors “negative habitual coping style” and “internalizing symptoms” needs to be considered. This high correlation can be explained by the operationalization of the two predictors: the traits “passive avoidance”, “continued mental preoccupation”, and “resignation” overlap considerably with depression contained in the variable “internalizing symptoms”. Possibly, “internalizing symptoms” could have been a significant predictor in a model without the predictor “negative habitual coping styles”. Nevertheless, “negative habitual coping style” is obviously the stronger predictor in this dataset.

Altogether, pediatric headache remission is difficult to predict. The selected psychological variables had only little prognostic value under these particular assessment conditions. We obviously need many more research attempts to explore influencing factors of headache remissions in different age grades, with different headache types, over different time intervals, in different samples, and with different biopsychosocial variables as predictors.

Acknowledgments

The research project has been supported by a grant from the German Ministry of Education and Research within the German Headache Consortium.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- BaslerHDFranzCKröner-HerwigBPsychologische Schmerztherapie: Grundlagen–Diagnostik–Krankheitsbilder–Schmerz–Psychotherapie. [Psychological Pain Therapy: Basics, diagnosis, pain syndromes, psychotherapy]HeidelbergSpringer2004 German

- Kröner-HerwigBSchmerz als biopsychosoziales Phänomen – eine Einführung. [Pain as a biopsychosocial phenomenon. An introduction]Kröner-HerwigBFrettlöhJKlingerRNilgesPSchmerz-psychotherapie. [Pain Psychotherapy]HeidelbergSpringer2011541563 German

- Kröner-HerwigBGassmannJHeadache disorders in children and adolescents: their association with psychological, behavioral, and socioenvironmental factorsHeadache20125291387140122789010

- McGrathPAHillierLMRecurrent headache: triggers, causes, and contributing factorsProg Pain Res Manag20011977107

- Roth-IsigkeitAThyenUStövenHSchwarzenbergerJSchmuckerPPain among children and adolescents: restrictions in daily living and triggering factorsPediatrics20051152e152e16215687423

- GaßmannJKopfschmerzen bei Kindern und Jugendlichen: Verlauf und Risikofaktoren. [Headache in children and adolescents: course and risk factors]dissertationGöttingenGeorg-August-Universität2009 German

- GassmannJMorrisLHeinrichMKröner-HerwigBOne-year course of paediatric headache in children and adolescents aged 8–15 yearsCephalalgia200828111154116218727649

- TermineCFerriMLivettiGMigraine with aura with onset in childhood and adolescence: long-term natural history and prognostic factorsCephalalgia201030667468120511205

- ScherAIStewartWFRicciJALiptonRBFactors associated with the onset and remission of chronic daily headache in a population-based studyPain20031061818914581114

- Abu-ArafehIRazakSSivaramanBGrahamCPrevalence of headache and migraine in children and adolescents: a systematic review of population-based studiesDev Med Child Neurol201052121088109720875042

- GaßmannJBarkeAvan GesselHKröner-HerwigBSex-specific predictor analyses for the incidence of recurrent headaches in German schoolchildrenPsychosocial Med20129 Doc03

- GaßmannJVathNvan GesselHKröner-HerwigBRisk factors for headache in childrenDtsch Ärztebl Int200910631–3250951619730719

- KienbacherCHWöberCHZeschHEClinical features, classification and prognosis of migraine and tension-type headache in children and adolescents: a long-term follow-up studyCephalalgia200626782083016776697

- van GesselHGaßmannJKröner-HerwigBChildren in pain: recurrent back pain, abdominal pain, and headache in children and adolescents in a four-year-periodJ Pediatr20111586977983e1e221232770

- FendrichKVennemannMPfaffenrathVHeadache prevalence among adolescents–the German DMKG headache studyCephalalgia200727434735417376112

- AnttilaPSouranderAMetsähonkalaLAromaaMHeleniusHSillanpääMPsychiatric symptoms in children with primary headacheJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry200443441241915187801

- KarwautzAWöberCLangTPsychosocial factors in children and adolescents with migraine and tension-type headache: a controlled study and review of the literatureCephalalgia1999191324310099858

- GuidettiVGalliFEvolution of headache in childhood and adolescence: an 8-year follow-upCephalalgia19981874494549793696

- BrnaPDooleyJGordonKDewanTThe prognosis of childhood headache: a 20-year follow-upArch Pediatr Adolesc Med2005159121157116016330740

- GoubertLVlaeyenJWCrombezGCraigKDLearning about pain from others: an observational learning accountJ Pain201112216717421111682

- McGrathPHeadache in children: the nature of the problemMcGrathPHillierLThe Child with Headache: Diagnosis and Treatment. Progress in Pain Research and ManagementSeattleIASP Press20012956 German

- Bandell-HoekstraIAbu-SaadHHPasschierJKnipschildPRecurrent headache, coping, and quality of life in children: a reviewHeadache200040535737010849029

- Kröner-HerwigBMorrisLHeinrichMBiopsychosocial correlates of headache: what predicts pediatric headache occurrenceHeadache200848452954418042227

- MonasteroRCamardaCPipiaCCamardaRPrognosis of migraine headaches in adolescents: a 10-year follow-up studyNeurology20066781353135617060559

- LazarusRSPsychological Stress and the Coping ProcessNew YorkMcGraw-Hill1996

- LazarusRSFolkmanSStress, Appraisal, and CopingNew YorkSpringer1984

- Kröner-HerwigBPothmannRSchmerz bei KindernKröner-HerwigBFrettlöhJKlingerRNilgesPSchmerzpsychotherapie. [Pain Psychotherapy]HeidelbergSpringer2007171193 German

- WeickgenantALSlaterMAPattersonTLAtkinsonJHGrantIGarfinSRCoping activities in chronic low back pain: relationship with depressionPain1993531951038316396

- AchenbachTMThe classification of children’s psychiatric symptoms: a factor-analytic studyPsychol Monogr19668071375968338

- VirtanenRAromaaMKoskenvuoMExternalizing problem behaviors and headache: a follow-up study of adolescent Finnish twinsPediatrics2004114498198715466094

- ReissSPetersonRAGurskyDMMcNallyRJAnxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency, and the prediction of fearfulnessBehav Res Ther1986241183947307

- KemperCJDas Persönlichkeitsmerkmal Angstsensitivität: Taxon oder Dimension? – Eine Analyse mit dem Mischverteilungs-Raschmodell. [The personality feature anxiety sensitivity: taxon or dimension: an analysis with the Rasch model]HamburgKovac2010 German

- FussSPagéMGKatzJPersistent pain in a community-based sample of children and adolescents: sex differences in psychological constructsPain Res Manag201116530330922059200

- MartinALMcGrathPABrownSCKatzJAnxiety sensitivity, fear of pain and pain-related disability in children and adolescents with chronic painPain Res Manag200712426727218080045

- TsaoJCAllenLBEvansSLuQMyersCDZeltzerLKAnxiety sensitivity and catastrophizing associations with pain and somatization in non-clinical childrenJ Health Psychol20091481085109419858329

- BarskyAJGoodsonJDLaneRSClearyPDThe amplification of somatic symptomsPsychosom Med19885055105193186894

- GregoryRManringJWadeMPersonality traits related to chronic pain locationAnn Clin Psychiatry2005172596416075657

- RaphaelKGMarbachJJGallagherRMSomatosensory amplification and affective inhibition are elevated in myofascial face painPain Med20001324725315101891

- Kröner-HerwigBHeinrichMMorrisLHeadache in German children and adolescents: a population-based epidemiological studyCephalalgia200727651952717598791

- HeinrichMMorrisLKröner-HerwigBSelf-report of headache in children and adolescents in Germany: possibilities and confines of questionnaire data for headache classificationCephalalgia200929886487219250286

- Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache SocietyThe International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd editionCephalalgia200424Suppl 1916014979299

- JankeWErdmannGKallusKWStreßverarbeitungsfragebogen (SVF) mit SVF 120. [The stress-coping inventory]GöttingenHogrefe1997 German

- AchenbachTMManual for the Youth Self-report and 1991 ProfileBurlingtonUniversity of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry1991

- PetersonRAReissSAnxiety Sensitivity Index Manual2nd edWorthington, OHInternational Diagnostic Systems1993

- BarskyAJWyshakGKlermanGLThe somatosensory amplification scale and its relationship to hypochondriasisJ Psychiatr Res19902443233342090830

- HosmerDWLemeshowSApplied Logistic Regression (Second Edition)New YorkJohn Wiley and Sons2000

- FieldADiscovering Statistics using SPSS3rd edLondonSage2009

- LaurellKLarssonBMattssonPEeg-OlofssonOA 3-year follow-up of headache diagnoses and symptoms in Swedish schoolchildrenCephalalgia200626780981516776695

- HermannCBlanchardEBFlorHBiofeedback treatment for pediatric migraine: prediction of treatment outcomeJ Consult Clin Psychol19976546116169256562

- HouleTNashJMStress and headache chronificationHeadache2008481404418184284

- Kröner-HerwigBFrettlöhJBehandlung chronischer Schmerz-syndrome: Plädoyer für einen interdisziplinären TherapieansatzKröner-HerwigBFrettlöhJKlingerRNilgesPSchmerzpsychotherapie. [Pain Psychotherapy]HeidelbergSpringer2011314 German

- TrautmannELackschewitzHKröner-HerwigBPsychological treatment of recurrent headache in children and adolescents – a meta-analysisCephalalgia200626121411141417116091

- Van den BrinkMBandell-HoekstraENAbu-SaadHHThe occurrence of recall bias in pediatric headache: a comparison of questionnaire and diary dataHeadache2001411112011168599