Abstract

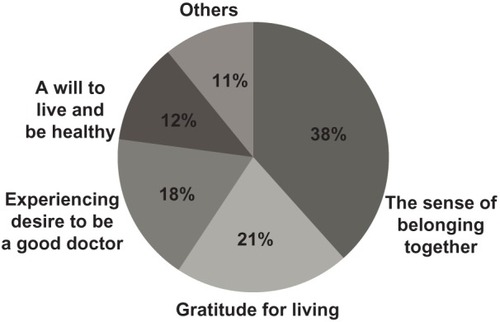

Pathography is defined as “historical biography from a medical, psychological, and psychiatric viewpoint.” We thought that writing about an experience of illness might help students understand patients’ experience and in turn grow in terms of self-understanding. Participants included 151 medical students. Students wrote about their own experience of illness and were asked to answer questions from the Likert scale. Most students wrote about themselves (79.2%); however, some students (20.8%) wrote about the illness of others. Among the 149 pathographies, ecopathography was most frequent (30.9%), followed by testimonial pathography (25.5%); angry pathography (13.4%) and alternative pathography (12.1%) were relatively less frequent. Eighty-eight pathographies (59.1%) showed 120 expressions of family relationship. Among the 120 cases, worrying about family members was most frequent (47.5%), followed by reliance on a family member (32.5%). All students wrote about the enlightenment experienced on returning to daily life. The sense of belonging together was most frequent (38.3%), followed by gratitude for living (20.8%), resolution to be a good doctor (18.1%), and a will to live and be healthy (12.1%). Answers on the Likert scale (total 5) for pathography beneficence were very high in understanding desirable doctor image (4.46), attaining morals and personality as a health care professional (4.49), and understanding basic communication skills (4.46). Writing about an experience of illness allows students to better understand patients’ experience and to grow in self-understanding.

Introduction

Sick persons rely on their physicians for skilled diagnosis, effective therapy, and human recognition of their suffering. Despite significant progress in the medical field resulting in achievement of the first two of these goals, the capacity to fulfill the third goal seems to have diminished. Physicians are now turning to the humanities and disciplines such as literary studies to achieve equally essential progress in comprehending their patients’ suffering, with a goal of accompanying their patients through illnesses with empathy, respect, and effective care. Together with social and behavioral sciences and other disciplines in the humanities, literature and literary studies are contributing to this educational effort.Citation1

Patients and their families are giving voice to their suffering, finding ways to write of illness and to articulate – and therefore comprehend – what they endure in sickness.Citation2

The call for a narrative in medicine has been touted as the cure-all for an increasingly mechanical medical field. It has been claimed that the humanities might create more empathic, reflective, professional, and trustworthy doctors.Citation3 By telling of what we undergo in illness or in the care of the sick, we are coming to recognize the layered consequences of illness and to acknowledge the fear, hope, and love exposed in sickness.Citation2

Subjects of pathography (defined as “historical biography from a medical, psychological, and psychiatric viewpoint”), have traditionally been famous people in all areas of human achievement.Citation4 According to the proverb “only the wearer knows where the shoes pinch,” we hypothesized that writing about an experience of illness might help medical students to understand patients’ experience and to grow in self-understanding; the goal of this paper was therefore to see if writing about an experience of illness did indeed result in these benefits.

Participants and methods

Participants

Participants included medical students in the three freshman classes (first year of a four-year course of medical school) from 2010–2012. There were 149 participants, 103 males and 44 females, 48–52 per year. The mean overall age was 26.6 ± 3.0 years (range: 21–36 years). In the PPS subject (Patient, Physician, and Society) lecture, a 10 minute-long introductory lecture about pathography was given to students using 12 slides. Students were allowed to write about their own experience of illness for 60 minutes. In the class, seven students presented their experiences via an open forum, and others submitted reports.

Students were asked to answer questions on the Likert scale regarding whether writing their pathography benefited them in understanding the basic skills of communication, understanding desirable doctor image, and attaining morals and personality as a health care professional.

Analysis

A graduate student read the written works and made a table; through initial discussion, categories were formed and revised, and disagreements were reconciled through repeated follow-up discussion. The following items were then extracted.

Whose illness?

Illness was identified as either affecting the student themself or affecting another person (family member, close friend, and teacher).

Pathography types

Pathographies written by the students were classified as four types according to Hawkins:Citation5,Citation6 testimonial pathography; angry pathography; alternative pathography; and ecopathography. Testimonial pathography blends practical information with personal accounts of the experience of illness and treatment in order to help others. Angry pathography is motivated by a strong need to point out deficiencies in various aspects of patient care. Alternative pathography is concerned not so much with criticizing traditional medicine as with finding alternative treatment modalities. Ecopathography links a personal experience of illness with larger environmental, political, or cultural problems.

Type of illness

Types of illness were classified as medical illness, surgery, cancer, neurological disease, or infectious disease.

Presence of pain in the pathography

Physical pain or psychological agony expressed in the pathography was evaluated. We checked if physical pain or psychological agony was expressed or whether it was not mentioned.

Family relationship

Presence of family relationship and its detail (eg, had reliance on family members, felt burdened, felt sorry, became an object of love or a hate figure) was evaluated.Citation7

Relationship to medical team

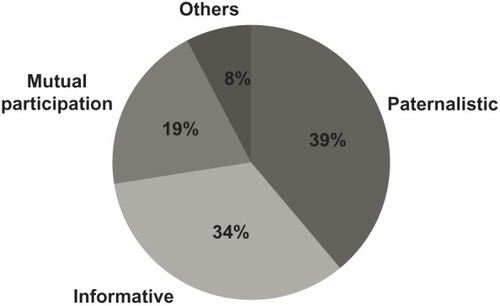

The relationship to the medical team was classified according to the Szasz and Hollander model.Citation8 In the paternalistic–priestly model (activity–passivity model),Citation8 the physician is active, the patient is passive, and treatment takes place irrespective of the patient’s contribution and regardless of the outcome. In the informative–consumer model (guidance–cooperation model)Citation8 both persons are ‘active’ in that they contribute to the relationship and what ensues from it. The more powerful of the two in the relationship (physician) will speak of guidance or leadership and will expect cooperation of the other member (patient). In the mutual participation model the participants have approximately equal power, are mutually interdependent, and engage in activity that will be satisfying in some ways to both.

Finding enlightenment on returning to daily life

Spiritual enlightenment on returning to daily life was evaluated and classified as follows: (1) gratitude for living; (2) a will to live and be healthy; (3) the sense of belonging together; and (4) resolution to be a good doctor.Citation7

Results

Whose illness?

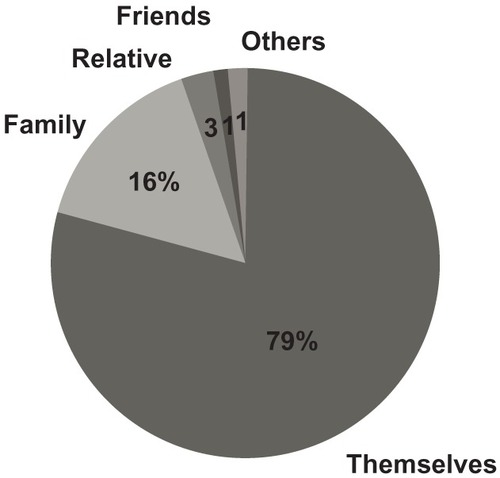

Most of the students wrote about themselves (118 cases, 79.2%); however, some students (31 cases, 20.8%) wrote about the illness of others (family members [23 cases, 15.4%], relatives [four cases, 2.7%], and friends [two cases, 1.3%]) ().

Pathography types

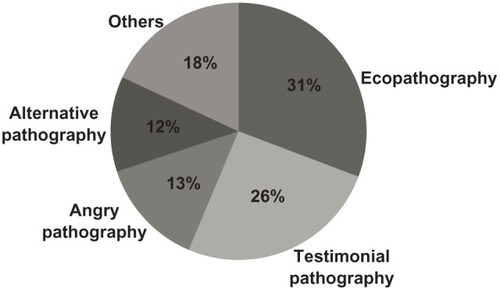

Among the 149 pathographies, ecopathography was most frequent (46 cases, 30.9%), followed by testimonial pathography (38 cases, 25.5%). Angry pathography (20 cases, 13.4%) and alternative pathography (12.1%) were relatively less frequent ().

Quotes of testimonial pathography included “When ill, a caring person gives me the power to overcome the disease” or “It is wise to receive treatment when (I) become sick.” Angry pathography quotes included “Neither doctor nor nurse gave me warm words” or “Unnecessary tests were done on me.” Alternative pathography quotes included “Several areas of the injured ankle were pierced by spit and blood was pulled out” or “I had acupuncture and massage therapy at a traditional medicine clinic because my symptoms remained after the hospital treatment.” Ecopathography quotes included “The environment surrounding me at that time made it more painful for me”, or “Watching that cancer patient and their family, I reflected on my situation and on my life.”

Type of illness

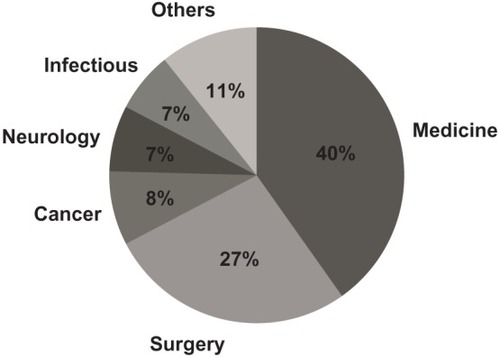

Medical illness was cited most frequently (60 cases, 40.3%), followed by surgery (40 cases, 26.8%). Cancer (12 cases, 8.1%), neurological disease (11 cases, 7.4%), infectious disease (10 cases, 6.7%), and 16 remainders included eruption of third molar teeth, burns, allergy, abrasion, strabismus and ankle sprain laceration ().

Presence of pain in the pathography

In most cases (139 cases, 93.3%), physical pain or psychological agony was expressed. However, in 10 cases, (6.7%), there was no mention of any pain.

Family relationship

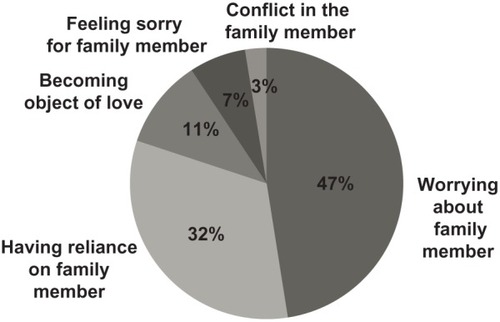

Among the 149 pathographies, 88 pathographies (59.1%) showed 120 expressions of family relationship including details. Among the 120 cases, worrying about family members was most frequent (57 cases, 47.5%), followed by having reliance on (a) family member (39 cases, 32.5%). Becoming an object of love (13 cases, 10.8%), feeling sorry for family members (eight cases, 6.7%), and conflict in family members (three cases, 2.5%) comprised the remainder of the cases ().

Relationship to the medical team

The paternalistic–priestly model was most frequent (58 cases, 38.9%), followed by the informative–consumer model (50 cases, 33.6%), and mutual participation model (29 cases, 19.5%) ().

Figure 5 Relationship to the medical team as classified according to the Szasz and Hollander model.Citation8

Finding enlightenment on returning to daily life

All 149 students wrote about the enlightenment experienced on returning to daily life. Regarding spiritual enlightenment on returning to daily life, the sense of belonging together was most frequent (57 cases, 38.3%), followed by gratitude for living (31 cases, 20.8%), resolution to be a good doctor (27 cases, 18.1%), and a will to live and be healthy (18 cases, 12.1%) ().

Students’ feedback

Answers on the Likert scale for pathography beneficence were very high in understanding the desirable doctor image (4.46 ± 0.75), attaining morals and personality as a health care professional (4.49 ± 0.69), and understanding the basic skills of communication (4.46 ± 0.69).

Discussion

In modern western medicine the predominant model for the body is that of a machine.Citation9 Practitioners of the biomechanical model reduce the patient to separate, individual body parts in order to diagnose and treat disease. Alternative models of the body, such as the phenomenological model, have been proposed to address this crisis.Citation9 According to the phenomenological model, the patient is viewed as an embodied person within a lived context and through this view the physician comes to understand the disruption illness causes in the patient’s everyday world of meaning.Citation9

Man is a storytelling animal. Human experience is understood, reconstructed, and transmitted as a narrative form; we seek the meaning of life from the narrative.Citation10 In medicine, a long tradition of narrative has existed since antiquity. The doctor has always tried to listen and understand the narrative of the patient and approach the suffering of the patient through the narrative. However, the more advanced modern medicine has become through the biotechnology, the greater the decline in the narrative tradition of the medicine.Citation10

Pathographies are a veritable gold mine of patient attitudes and assumptions regarding all aspects of illness. The narratives can be especially useful to physicians at a time when they are given less and less time to get to know their patients, but are still expected to be aware of their patients’ wishes, needs, and fears.Citation4 According to Hawkins, when pathographies are analyzed according to author intent, four different groups of pathographies emerge.Citation3,Citation4

In our study, ecopathography was the most frequent pathography (30.9%), followed by testimonial pathography (25.5%). Angry pathography (13.4%) and alternative pathography (12.1%) were relatively less frequent.

We thought that writing about an experience of illness should be included in the study of literature. In the feedback from the medical students, writing about an experience of illness benefited the medical students in understanding what constituted a desirable doctor image and assisted in attaining morals and personality as a health care professional; all of the students experienced enlightenment on returning to daily life after their experience of illness. The sense of belonging together was felt most frequently (38.3%), followed by a gratitude for living (20.8%), resolution to be a good doctor (18.1%), and a will to live and be healthy (12.1%).

In our study, answers on the Likert scale for pathography beneficence were very high in understanding the importance of a desirable doctor image (4.46 ± 0.75), attaining morals and personality as a health care professional (4.49 ± 0.69), and understanding the basic skills of communication (4.46 ± 0.69).

Most of the pathographies written by medical students did not contain severe illness leading to death, which is a limitation of this study. Further studies may be conducted for medical doctors, nurses, or nursing students. The comparison of the results from each group of health professionals might be enlightening.

Conclusion

In this study, writing about an experience of illness allowed students to better understand patients’ experience and to grow in self-understanding. We hope that writing about an experience of illness will allow medical students to more accurately construct the lives of their patients and to recognize the human dimensions of all of the experiences that occur within their gaze.

Acknowledgments

Kun Hwang is a Fellowship Professor at the Inha University School of Medicine and teaches Literature and Medicine. Fan Huan is a graduate student at the Inha University School of Medicine. Se Won Hwang is a medical student at the Peninsula Medical School, Exeter, UK.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CharonRBanksJTConnellyJELiterature and medicine: contributions to clinical practiceAnn Intern Med199512285996067887555

- CharonRNarrative medicine: attention, representation, affiliationNarrative2005133261270

- BishopJPRejecting medical humanism: medical humanities and the metaphysics of medicineJ Med Humanit2008291152518058003

- SchioldannJAWhat is pathography?Med J Aust2003178630312633495

- HawkinsAHReconstructing Illness: studies in PathographyWest Lafayette, IndianaPurdue University Press1999

- HawkinsAHPathography: patient narratives of illnessWest J Med1999171212712910510661

- HwangIKMedicine and Narrative. A Dissertation for Doctor of Philosophy in MedicineSeoul National UniversitySeoul, Korea122010

- SzaszTSHollenderMHA contribution to the philosophy of medicine; the basic models of the doctor-patient relationshipAMA Arch Intern Med195697558559213312700

- MarcumJABiomechanical and phenomenological models of the body, the meaning of illness and quality of careMed Health Care Philos20047331132015679023

- HwangIK[The illness experience and illness narrative]Philosophy of Medicine201010328 Korean