Abstract

Empathy is important to patient care. It enhances patients’ satisfaction, comfort, self-efficacy, and trust which in turn may facilitate better diagnosis, shared decision making, and therapy adherence. Empathetic doctors experience greater job satisfaction and psychological well-being. Understanding the development of empathy of tomorrow’s health care professionals is important. However, clinical empathy is poorly defined and difficult to measure, while ways to enhance it remain unclear. This review examines empathy among undergraduate medical students, focusing upon three main questions: How is empathy measured? This section discusses the problems of assessing empathy and outlines the utility of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy – Student Version and Davis’s Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Both have been used widely to assess medical students’ empathy. Does empathy change during undergraduate medical education? The trajectory of empathy during undergraduate medical education has been and continues to be debated. Potential reasons for contrasting results of studies are outlined. What factors may influence the development of empathy? Although the influence of sex is widely recognized, the impact of culture, psychological well-being, and aspects of undergraduate curricula are less well understood. This review identifies three interrelated issues for future research into undergraduate medical students’ empathy. First, the need for greater clarity of definition, recognizing that empathy is multidimensional. Second, the need to develop meaningful ways of measuring empathy which include its component dimensions and which are relevant to patients’ experiences. Medical education research has generally relied upon single, self-report instruments, which have utility across large populations but are limited. Finally, there is a need for greater methodological rigor in investigating the possible determinants of clinical empathy in medical education. Greater specificity of context and the incorporation of work from other disciplines may facilitate this.

Introduction

The Francis Report into the systemic failings at the UK Mid-Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust emphasized the importance of empathy in health care.Citation1 Understanding what influences the empathy of tomorrow’s health care professionals is as important as ensuring their clinical competence. However, clinical empathy remains poorly defined and difficult to measure, while ways to enhance it remain unclear.

Studies have shown that clinical empathy enhances patient satisfaction, comfort, and trust.Citation2–Citation5 Patients who trust their doctors are more likely to be open and to provide more detailed information enabling better diagnosis and shared decision making.Citation6,Citation7 Patients’ belief in their own ability to cope in a specific situation (self-efficacy) may facilitate adherence to therapy.Citation8,Citation9 Receipt of empathy may be therapeutic in its own right.Citation10–Citation14

Empathetic doctors appear to experience greater job satisfaction and psychological well-beingCitation15 and have been found to make better clinical decisionsCitation16–Citation19 and to be more effective transformational leaders.Citation20

Despite recognition of the benefits of empathy, the concept of clinical empathy is relatively poorly defined.Citation21–Citation23 This contrasts with definitions of empathy in fields such as psychology, child development, and criminology.Citation24,Citation25 Prior to the 1990s, there was little research into the role empathy played in effective medical care. Several writers formulated operational definitions.Citation26 Mercer and Reynolds,Citation27 view of clinical empathy was the ability to:

understand the patient’s situation, perspective, and feelings (and attached meanings),

communicate that understanding and check its accuracy, and

act on that understanding with the patient in a helpful (therapeutic) way.Citation27

This definition implies a multidimensional construct incorporating affective, cognitive, behavioral, and moral components. Neuroscience research supports the distinction between the cognitive and affective components of empathy,Citation28,Citation29 as do studies investigating mental disorders, child development, and criminology.Citation24,Citation30,Citation31 Research into the impact of communication skills training in medical education suggests that it fosters empathetic behavior.Citation32

Medical education research has tended to focus on the cognitive and affective dimensions of empathy, which are relatively easy to measure. Far less attention has been given to the moral dimension. Understandably, the focus has also been on measuring empathy directed toward another person. Neurological evidence suggests that parts of the brain associated with feeling pain are affected when watching someone else’s pain.Citation33 However, few studies have addressed such potentially negative effects of empathy on medical students or physicians.

This paper presents an overview of current issues relating to the study of undergraduate medical students’ empathy. We focus on three main questions.

How is empathy measured?

Does empathy change during undergraduate medical education?

What factors may influence the development of medical students’ empathy?

The paper concludes by suggesting future directions for the study of medical students’ empathy.

Methodology

This paper is not a full systematic review. It draws upon extensive literature searches conducted as part of the authors’ work. Searches using the terms “empathy and students” were undertaken in “PubMed” and “Scopus”. For studies relating to empathy in the fields of psychology, child development, and criminology, search terms were extended to “empathy and young people”. For work in psychology, we also conducted hand searches of journals noted for their publication of studies of empathy.

How is empathy measured?

Background

For patients, the empathetic behavior they receive is important. However, observing the behavioral expression of empathy in the clinical setting is difficult. Asking patients to assess medical students’ empathy is problematic, not least because of ethical and time issues. In addition, when patients are involved with students in an educational context, they frequently express the desire to be “helpful” and “give something back”.Citation34 Such altruistic motives undermine objective assessment. There is also the problem of what the patient perceives: is it empathy or communication style – and are the two the same?Citation35

Assessment of medical students’ empathy has tended to rely on observation by faculty, rating by standardized or simulated patients (SPs), and self-report measures. Varying degrees of agreement between these have been reported.Citation36–Citation39 SPs’ assessments may be “socially constructed” relating to personal experiences.Citation40 The lack of strong associations between students’ scores on self-report instruments and observations of their behavior has led some commentators to question whether students are simply “performing or faking” the behavior needed.Citation41 This raises questions about the impact of such behavior on patients if it is devoid of sincerity. Studies in psychology have found differences between self-report measures and empathetic accuracy, that is, between what a respondent believes his/her empathetic abilities to be and how good that respondent is at rating another person’s affective state.Citation42

Medical education research has relied strongly on self-report instruments. A review of empirical research on empathy in medicine by Hemmerdinger et al identified 36 different measures, of which 14 were self-report instruments.Citation23 A further review of 38 instruments found that 26 did not explicitly state which dimensions of empathy were being measured.Citation22

Two widely used self-report instruments

Two self-report instruments that reflect the multidimensional nature of empathy have been widely used to assess undergraduate medical students’ empathy.

Jefferson Scale of Empathy – Student Version

Developed specifically to measure empathy in respect of patient care, the psychometric properties of the JSE-S have been well tested and documented.Citation23,Citation43 Reflecting the cognitive and affective dimensions of empathy, the Jefferson Scale of Empathy – Student Version (JSE-S) comprises 20 items relating to three underlying components: Perspective Taking (ten positively worded items), Compassionate Care (eight negatively worded items), and Standing in the Patient’s Shoes (two negatively worded items). Respondents rate their level of agreement with statements on a seven-point Likert scale, higher scores indicating higher levels of agreement. The JSE-S has been extensively used with medical students and other health care profession studentsCitation44,Citation45 and with medical students in different countries.Citation46–Citation48

Davis’s Interpersonal Reactivity Index

Davis built on his work in child development and prosocial behavior in adults to devise the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI).Citation49 The IRI comprises 28 items (19 positive, nine negative), forming four, seven-item, subscales. Davis described these as a set of related but clearly discriminable constructs, concerning responsivity to others.Citation50

The IRI’s four subscales are Perspective Taking (IRI-PT): which assesses the other person’s psychological point of view, Empathetic Concern (IRI-EC): which assesses feelings and concerns for the other person, Personal Distress (IRI-PD): which measures personal feelings of anxiety and unease in tense interpersonal settings, and Fantasy Scale (IRI-FS): which assesses the tendency to transpose oneself imaginatively into the feelings and actions of fictional characters. IRI-EC and IRI-PT are “other-directed”, whereas IRI-PD and IRI-FS are “self-directed”. Respondents rate the extent to which statements describe themselves on a five-point Likert scale.

The use of the IRI in varying contexts provides a useful basis for comparison. It has been used to examine clinical conditions affecting social functioning and emotions, such as paranoid schizophrenia and Parkinson’s diseaseCitation51,Citation52; the development of prosocial behavior among adults and adolescentsCitation53,Citation54; the neurological basis of cognitive and affective empathyCitation28; and the assessment of juvenile and sex offenders.Citation55 It has also been used among US college students.Citation56

Relationship between the JSE-S and IRI scales

The JSE-S has become the preferred instrument for assessing medical students’ empathy. Work using both scales, enabling an understanding of the relationship between them, is rare. The authors have recently collaborated with colleagues in Portugal and Brazil in a study examining the underlying factor structures and relationships between the JSE-S and the IRI using data from five countries.Citation57 This work suggests that the IRI and JSE-S are only weakly related and measure different constructs. The level of similarity of mean scores from different populations (excluding offenders) suggests that the IRI measures generic or dispositional empathy. By contrast, the JSE-S measures empathy within a health care context. As discussed later, this distinction could have important implications for both medical education and medical education research.

Establishing norms

It would be informative to understand the level of empathy that students have when beginning their course in relation to their age-related peers and similar students in other cultures. There is little comparative work, so that clear “norms” are difficult to establish. Nevertheless, after reviewing several studies, Hojat and Gonnella have suggested norms for the JSE-S.Citation58 presents results of recent international studies using the JSE-S in relation to these norms. Few studies report mean scores lower than the “low scorer” tentative cut-offs suggested by Hojat and Gonnella of ≤95 for men and ≤100 for women.Citation58

Table 1 Results of a sample of recent studies of medical students’ empathy using the JSE-S in different countriesTable Footnotea

The IRI enables comparison of medical students with other populations, since Davis’s suggested norms were based on general population studies. Although the use of the IRI among medical students is less widespread, results from recent studies of medical students, comparable nonmedical students, and offenders are presented together with Davis’s norms in . Few studies of medical students report mean scores for either the IRI-EC or IRI-PT below Davis’s norms (). Evidence from psychology and criminology suggests that, unsurprisingly, some people with particularly low levels of empathy may display behaviors that would be inappropriate for a caring profession.Citation53,Citation54,Citation59

Table 2 Results of a sample of recent studies of medical students’ empathy using the IRI compared to other populationsTable Footnotea

Summary

The measurement of medical students’ empathy has relied heavily on the use of self-report instruments; the two most widely used being the JSE-S and IRI. Although they have the utility of being easily administered to large numbers of students, the extent to which they measure empathetic behavior is questionable. Recent evidence suggests that the JSE-S and IRI are weakly related and measure different constructs. However, the establishment of “norms” for both instruments can facilitate comparison of medical students and the extent to which medical students differ from their age-related peers.

Does empathy change during undergraduate medical education?

Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies undertaken early in this century suggested that empathy declined during undergraduate medical education.Citation60–Citation62 From 2005, the number of studies examining the trajectory of undergraduate medical student expanded, but results were mixed. Studies in India, Iran, the UK, the USA, and the Caribbean supported the view that empathy declined.Citation46,Citation47,Citation63–Citation65 Studies in Portugal, Korea, Japan, Iran, Bangladesh, the USA, Croatia, Brazil, and the UK reported either no change or an increase in empathy.Citation66–Citation75 Unsurprisingly, systematic reviews have also produced mixed results. A review by Neumann et al concluded that empathy declined,Citation76 but a recent systematic review by Roff disputes this.Citation77

Mixed results have also been reported about both the timing of the decline in empathy and the extent of sex differences in the trends displayed. Several studies suggest that empathy diminishes early in the undergraduate course, during phases devoted primarily to biomedical sciences.Citation78,Citation79 Other studies indicate that the decline occurs later, during more clinically oriented phases.Citation80–Citation82

The authors undertook a longitudinal study examining four cohorts of students entering one medical school between 2007 and 2010.Citation83 The school provides a 6-year course, comprising a preclinical component devoted mainly to biomedical sciences with some clinical contact (years 1–3) and a clinical component (years 4–6). Students beginning each component were surveyed annually at the start of the academic year. Response rates ranged from 53% to 57% in the preclinical years and from 55% to 65% in the clinical years. Over 700 students in the preclinical component and >400 students in the clinical component participated. More than 60% in each component completed the survey more than once, and 66 students took part in all 6 years. Using the IRI, we found a statistically significant but small decline only in affective empathy (IRI-EC) and only among male students during the preclinical component. No changes in either affective or cognitive empathy were displayed by female students during either component of the course.Citation83 In common with other studies, our work questioned the practical significance of the observed changes in empathy. This issue has been widely debated.Citation84

We extended our longitudinal study to 18 medical schools: 16 in the UK, one in New Zealand, and one in Ireland.Citation85 We undertook a cross-sectional study which examined whether students nearing completion of their course recorded lower scores for empathy than those starting it. We used both the IRI and JSE-S. Response rates varied between schools and within schools between years, ranging from 7% to 78%. Overall, 954 students nearing completion of their course did not record lower scores on any measure of empathy than 1,373 medical students beginning their course. No differences were found between male and female students in this respect, although female students recorded significantly higher empathy scores than males.Citation85

The factors discussed as follows may explain some of the inconsistency in the results of these wide-ranging studies.

Cross-sectional and single-institution studies

Many studies of undergraduate medical students’ empathy have been cross-sectional, comparing empathy in different cohorts.Citation76,Citation77 Differences in course content and structure may confound multi-institution studies, while in single-institution study, cohorts may differ. The difficulties of undertaking longitudinal work are reflected in the small number of such studies. Those that have been undertaken, such as the authors’ own work, have usually been conducted in only one institution and have involved relatively few students.Citation83 The single-institution focus and small number of participants make it difficult to generalize findings from small-scale cross-sectional and/or longitudinal studies.Citation82,Citation83

Measurement

Another problem is the tendency to use a single self-report instrument. This raises questions as to whether results using different instruments are truly comparable. In a recent study, the authors combined data from their cross-sectional study involving medical schools in the UK, New Zealand, and Ireland with data obtained by colleagues in Brazil and Portugal. The study examined the factorial structures and comparability of the JSE-S and this work suggested that the JSE-S and IRI are structurally different and measure only weakly related concepts. This may imply that results of studies using only one of the instruments may not be comparable with those using the other. It is likely that other instruments used to measure medical students’ empathy also differ in respect of the precise constructs measured.

Differences in different dimensions of empathy

Although empathy is recognized to be multidimensional, few studies report the dimension of empathy in which the change occurs. The structure of the JSE-S would enable changes in the affective and cognitive dimensions of empathy to be observed; however, there is a tendency for studies using the JSE-S to report only the total score. In common with other studies using the IRI, the authors’ single-institution study found a small change only in affective empathy.Citation83

Context

Frequently studies examining medical students’ empathy fail to report potentially important confounding variables, such as age and sex. (These factors are discussed later.) There is also a notable lack of details of course content and structure. We do not know whether problem-based or integrated courses help develop or preserve empathy. This lack is compounded by differences in ages and experience at admission. In the UK and much of Europe, most students enter medical training between the ages of 18 and 21. In North America, most of those entering medical training are at least 21.

Summary

There is no systematic evidence that undergraduate medical education diminishes empathy (nor is there evidence that it enhances empathy). This challenges the widely held view that medical education is inevitably associated with a decline in empathy. Nevertheless, the literature continues to offer a mixed picture, possibly related to limitations and differences in study design. Few studies are longitudinal and many focus on single institutions; details of study context, respondent sex, and different empathy components are often lacking; and different instruments appear to measure different constructs.

What factors may influence the development of empathy?

Age

Although there is some evidence that empathy increases with age,Citation86 work comparing medical students who differ in age when they start their course is scarce. Attempts to widen access to medical education during the last decade have seen the development of accelerated graduate entry courses in the UK and elsewhere in Europe. Such courses typically last for 4 years as compared to 5/6 years for “standard entry” students. The authors’ recent work with undergraduate medical students in the UK, Ireland, and New Zealand found that, at the beginning of their course, graduate entry course students recorded significantly higher mean scores for the JSE-S and IRI-PT, and significantly lower mean scores for IRI-PD than standard entry course students. No differences were found in respect of IRI-EC. Differences in the JSE-S, although statistically significant, were small in terms of effect size. Effect sizes of differences in IRI-PT and IRI-PD were larger.Citation85 However, age alone may not explain this difference. Compared to standard entry, graduate entry students may be making a more conscious choice based on life experiences.

Sex

Empathy is widely considered to be normally distributed in the general population, but females have been found to record higher scores on self-report measures.Citation24 A few studies have found no sex differences in the empathy scores reported by undergraduate medical students.Citation67,Citation70,Citation79 In contrast, many studies in disparate cultural settings including Asia, Europe, and the Americas support the view that female medical students record higher empathy scores than their male counterparts.Citation46,Citation48,Citation66,Citation68,Citation73–Citation75,Citation82,Citation83

Unfortunately, few studies investigate and describe how the empathy recorded by male and female student differs over time. Where such details have been given, evidence suggests that female students show greater stability in respect of scores for “other directed” empathy than male students.Citation82,Citation83,Citation85 However, because few studies have included self-directed personal distress (IRI-PD), the question remained as to whether female medical students record higher levels of personal distress and whether, as a result, they are more vulnerable.

Culture

Culture may also have an impact. Differences in scores for the JSE-S have often been observed in studies of medical students in different countries.Citation46–Citation48,Citation65,Citation66 Studies of students in Asian medical schools frequently report lower scores than studies undertaken in North American and European ones (). These differences have been ascribed to communication patterns which place less emphasis on nonverbal communication, the disposition of doctors preferred and expected by patients, the strongly science-oriented selection system among Asian medical schools, as well as differences in medical education per se.Citation48,Citation68 Whether these observed differences hold practical significance for medical practice in different cultural environments remain unclear. There has been little work examining the extent to which different cultural normative values influence empathy. A few studies have examined the relationship between values and empathy, but these have been conducted within the same broad cultural setting.Citation87,Citation88

Psychological well-being

Specific psychiatric disorders have been found to be strongly associated with lower scores in certain dimensions of empathy.Citation89 Lower scores for cognitive empathy have been found to be associated with autism and offenders, whereas lower scores for affective empathy have been found to be associated with psychopathy.Citation24,Citation90

Associations have also been found between depression and perspective-taking abilities.Citation91 When chronically depressed patients have been compared to controls, they have been found to have lower levels of perspective taking (IRI-PT) and higher levels of personal distress (IRI-PD) but no impairment of affective empathy (IRI-EC).Citation92 Similar differences in empathy have been found among people suffering from bipolar disorder.Citation93 However, the extent to which the relationships found between empathy and severe mental health disorders can be applied to medical students is questionable.

It is frequently argued that psychological distress is prevalent among medical students to a greater extent than among the general population, age-related peers, and nonmedical student peers.Citation94–Citation96 It is also suggested that medical students’ psychological well-being deteriorates during medical education.Citation94–Citation96 Such views are not universally supported.Citation97–Citation99 Both the effect of psychological distress on medical students’ empathy and the line of causality are uncertain.Citation97,Citation100,Citation101 Studies in North America report depression to be inversely related to empathy among women and burnout to be negatively correlated with empathy among all students.Citation95

The authors’ recent study involving 2,474 medical students in the UK, Ireland, and New Zealand found extremely weak negative correlations between depression scores as measured by HADS-D and empathy scores as measured by IRI-EC, IRI-PT, and JSE-S (Pearson correlation coefficients of, respectively, −0.042, −0.078, and −0.082). In contrast, stronger positive correlations were found between scores for both anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D) and IRI-PD (personal distress) (Pearson correlation coefficients of, respectively, 0.312 and 0.220).Citation85

The potential differential impact of each dimension of empathy may have important implications for medical education. For example, a study of medical students’ judgments of pain-related symptoms found that students who recorded higher affective empathy scores (IRI-EC) were more likely to accept what patients say and rate symptoms as more severe than students recording lower affective empathy scores.Citation101 By contrast, a small-scale Finnish study found that personal distress (IRI-PD) was negatively related to care-based moral development.Citation87

Aspects of the undergraduate course

Course structure in terms of the extent and timing of clinical experience may influence the development and maintenance of empathy. Low levels of integration of clinical experience have been cited as a possible reason for cultural differences in empathy scores.Citation68 A systematic review of the impact of early practical experience in medical training concluded that it fostered empathetic attitudes toward ill people.Citation102 Studies of specific initiatives that involve extended, repeated, or more intensive exposure to clinical experience, even where that experience is effected through SPs, tend to support this view.Citation40,Citation103,Citation104

The hidden curriculum may influence medical students’ empathy, and yet, its impact remains under-researched.Citation105 Many medical students report witnessing peers and supervisors making disparaging comments about, or references to, patients and colleagues, and reports of personal mistreatment by peers and faculty are not unusual.Citation106,Citation107 Medical students are often keenly aware of the empathy and communication skills displayed by clinical tutors and practicing clinicians that they observe when on placements.Citation108,Citation109

Can empathy be taught?

Empathy involves not only understanding the patient’s situation and feelings but also being able to communicate that understanding. Communications skills are now taught as part of the core curricula of all the UK medical schools, and yet, 2 decades ago, such skills were rarely a formal part of the UK medical education.Citation110 A review of intervention strategies aimed at enhancing empathy concluded that empathy was amenable positive change, with communication skills workshops addressing the behavioral aspects of empathy having the largest impact.Citation111 However, there may still be a gap between what is taught in communication skills and how this is transferred to the clinical context. A recent study highlighted the need for greater collaboration between educators in the academic and clinical environments.Citation112 Communication skills figure strongly in interventions aimed at enhancing empathy. In general, SPs involved in such interventions tend to report higher levels of satisfaction with encounters with the intervention group of students as compared to the control group of students.Citation113,Citation114

Reflective writing,Citation115 drama or role play,Citation116 and patient interviewsCitation117 are among methods used in interventions aimed at enhancing empathy. In a recent review, Batt-Rawden et al suggested that educational interventions could be successful in maintaining and enhancing undergraduate medical students’ empathy.Citation118 However, many interventions are evaluated over a relatively short time frame, and little is known about their longer term impact. Brazilian work suggests that there may well be a need to repeat such interventions over time.Citation104

Summary

Many factors may influence the development and maintenance of empathy among undergraduate medical students. At a general level, these include age, sex, psychological well-being, and culture. But aspects of the undergraduate course such as the context and timing of clinical experience, the hidden curriculum, the communication skills training, and the other specific educational interventions may also play an important role. However, these factors have not been the central focus of studies of medical students’ empathy hitherto.

Future directions

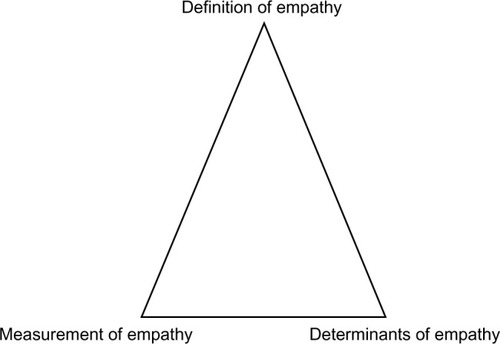

This review of research into medical students’ empathy sought to address its measurement, its change during the undergraduate course, and the factors that may influence it. Three interrelated issues can be said to emerge for future research into undergraduate medical students’ empathy ().

Definition of empathy

Empathy is multidimensional, but, as noted, there is a lack of work in medical education examining its different dimensions, their impact, and what influences them in a clinical context. Studies of medical students’ empathy frequently do not define or report results for different dimensions of empathy, yet the widely used JSE-S and IRI provide measures of affective and cognitive empathy. If such reporting were done in relation to educational interventions aimed at enhancing empathy, then a clearer picture would emerge as to whether empathy is amenable to being taught.

Possible negative impacts of empathy in terms of overidentification with the suffering of patients are unknown. This may help in understanding resilience among doctors, a key issue in modern medical practice. There is also a need to examine the impact of lack of empathy, incorporating moral and behavioral dimensions. This work would be strengthened by incorporating work from other disciplines, including the influence of normative values on attitudes, behavior, and decision making.

Measurement of empathy

Single, self-report instruments have the advantage of utility across large populations. The need for greater granularity in describing the dimension of empathy measured has already been suggested. However, there remain questions as to the measurement fidelity and comparability of self-report instruments. The development of the JSE-S and its widespread application have provided a basis for comparability. However, while the JSE-S is context specific, it remains unclear to what extent it measures a socially desirable view of the ideal doctor.

There is also the question about whether self-report instruments are relevant for the real-world clinical practice, as experienced by patients. The fidelity of self-report instruments could be enhanced by triangulation, such as using more than one instrument, and using them in conjunction with direct observation of empathetic practice, and simulated or real patients’ evaluations. Many instruments have been developed to assess patients’ experiences, yet few studies of medical students’ empathy incorporate these.Citation119

There is an overwhelming need for more qualitative work. We know little of what students regard as empathetic practice, and for example, how this relates to their normative values. More importantly, we know little about what students observe as empathetic practice and the context of that observation. Such work would highlight not only opportunities for enhancing empathy but also the impact of role models and the hidden curriculum. Qualitative work focusing on critical incidents, such as a student’s first experience of a patient’s death, would also help elucidate influences on context-specific empathy. Although difficult to undertake, both quantitative and qualitative longitudinal work could also help pinpoint the timing of nature of experiences, which influence changes in empathy.

Determinants of empathy

Current evidence does not support the contention that undergraduate medical education universally diminishes empathy. In addition, some of the changes observed may be of questionable practical significance. Nevertheless, there is a need to focus on developing a better understanding of what influences empathy and how empathy can be developed and enhanced.

Studies suggest that age, sex, and culture all influence empathy. There is a need for more studies comparing entrants to medical education who differ in age and relevant life experience. Despite evidence that female medical students record higher scores on self-report instruments measuring empathy, few studies report sex differences overtime. The impact of medical students’ psychological well-being on the different dimensions of empathy has also received little attention. Similarly, cross-cultural studies that take account of prevailing cultural norms and values and differences in medical practices and patients’ expectations of doctors are also rare.

A notable need is for more understanding of the impact of differences in course content and structure. There is a need for studies to describe, in more detail, aspects such as the timing, context, and nature of clinical experience. Such description needs to go beyond simplistic labels such as “integrated” or “problem-based”. However, achieving realistic sample sizes to investigate these relationships may remain challenging. Although short-term evaluations appear to support the view that educational interventions can enhance empathy, further investigation is needed into the longer term impacts of such interventions.

Conclusion

Existing work has gone a long way to describe the nature of empathy among medical students and factors that may influence it. Nevertheless, there remains a need for greater clarity of definition of empathy; for development of meaningful measures, relating to different components of empathy, and which are relevant to patients’ experience; and for studies with the methodological rigor to clarify those determinants of empathy which are amenable to influence by medical education. Greater specificity of context and the incorporation of work from other disciplines may facilitate this.

Investigation of the level, trajectory, and determinants of empathy in medical students during their education will remain difficult. Nevertheless, as a key component of good medical care, the underlying concept has perhaps never been more important.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- FrancisRReport of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry: executive summary http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20150407084003/http://www.midstaffspublicinquiry.com/reportAccessed March 10, 2015

- ThomDHPhysician behaviors that predict patient trustJ Fam Pract200150432332811300984

- KrupatEBellRAKravitzRLThomDAzariRWhen physicians and patients think alike: patient-centred beliefs and their impact on satisfaction and trustJ Fam Pract200150121057106211742607

- ReissHTClarkMSPereira GrayDJMeasuring the responsiveness in the therapeutic relationship: a patient perspectiveBasic Appl Soc Psychol2008304339348

- KimSSKaplowitzSJohnstonMVThe effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and complianceEval Health Prof200427323725115312283

- DerksenFBensingJLagro-JanssenAEffectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic reviewBr J Gen Pract201363606e76e8423336477

- ZachariaeRPedersenCGJensenABAssociation of perceived physician communication style with patient satisfaction, distress, cancer-related self-efficacy, and perceived control over the diseaseBr J Cancer200388565866512618870

- BanduraASelf-efficacy – The Exercise of ControlNew YorkFreeman and Company1997

- VermeireEHearnshawHVan RoyenPDenekensJPatient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive reviewJ Clin Pharm Ther200126533134211679023

- Del CanaleSLouisDZMaioVThe relationship between physician empathy and disease complications: an empirical study of primary care physicians and their diabetic patients in Parma, ItalyAcad Med20128791243124922836852

- HojatMLouisDZMarkhamFWWenderRRabinowitzCGonnellaJSPhysicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patientsAcad Med201186335936421248604

- RakelDBarrettBZhangZPerception of empathy in the therapeutic encounter: effects on the common coldPatient Educ Couns201185339039721300514

- NeumannMWirtzMBollschweilerEDeterminants and patient-reported long-term outcomes of physician empathy in oncology: a structural equation modelling approachPatient Educ Couns2007691–3637517851016

- PriceSMercerSWMacPhersonHPractitioner empathy, patient enablement and health outcomes: a prospective study of acupuncture patientsPatient Educ Couns2006631–223924516455221

- GleichgerrchtEDecetyJThe relationship between different facets of empathy, pain perception and compassion fatigue among physiciansFront Behav Neurosci2014824325071495

- LarsonEBYaoXClinical empathy as emotional labor in the patient-physician relationshipJAMA200529391100110615741532

- CoulehanJLPlattFWEgenerB“Let me see if I have this right… ”: words that help build empathyAnn Intern Med2001135322122711487497

- BeckmanHBFrankelRMTraining practitioners to communicate effectively in cancer care: it is the relationship that countsPatient Educ Couns2003501858912767591

- LevinsonWGorawara-BhatRLambJA study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settingsJAMA200028481021102710944650

- SkinnerCSpurgeonPValuing empathy and emotional intelligence in health leadership: a study of empathy, leadership behavior and outcome effectivenessHealth Serv Manage Res200518111215807976

- NeumannMBensingJMercerSAnalysing the “nature” and “specific effectiveness” of clinical empathy: a theoretical overview and contribution towards a theory based research agendaPatient Educ Couns200974333934619124216

- PedersenREmpirical research on empathy in medicine-a critical reviewPatient Educ Couns200976330732219631488

- HemmerdingerJStoddartSDLilfordRJA systematic review of tests of empathy in medicineBMC Med Educ200772417651477

- Baron-CohenSZero Degrees of EmpathyLondon, UKPenguin2011

- PosickCRocqueMRafterNMore than a feeling: integrating empathy into the study of lawmaking, lawbreaking, and reactions to lawbreakingInt J Offender Ther Comp Criminol201458152623188925

- HalpernJFrom idealized clinical empathy to empathetic communication in medical careMed Health Care Philos201417230131124343367

- MercerSWReynoldsWJEmpathy and the quality of careBr J Gen Pract200252SupplS9S1312389763

- LammCBatsonCDDecetyJThe neural substrate of human empathy: effects of perspective taking and cognitive appraisalJ Cogn Neurosci2007191425817214562

- WangQZhangZDongFAnterior insula GABA levels correlate with emotional aspects of empathy: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studyPLoS One2014911e11384525419976

- van LangenMAMWissinkIBvan VugtESVan der StouweTStamsGJJMThe relation between empathy and offending: a meta-analysisAggress Violent Behav2014192179189

- van NoordenTHHaselagerGJCillessenAHBukowskiWMEmpathy and involvement in bullying in children and adolescents: a systematic reviewJ Youth Adolesc201444363765724894581

- BarthJLannenPEfficacy of communication skills training courses in oncology: a systematic review and meta-analysisAnn Oncol20112251030104020974653

- JacksonPLMeltzoffANDecetyJHow do we perceive the pain of others? A window into the neural processes involved in empathyNeuroimage200524377177915652312

- BensonJQuinceTHibbleAFanshaweTEmeryJThe impact on patients of expanded, general practice based, student teaching: observational and qualitative studyBMJ200533175088915996965

- SilvesterJPattersonFKoczwaraAFergusonE“Trust me ….” Psychological and behavioral predictors of perceived physician empathyJ Appl Psychol200792251952717371096

- O’ConnorKKingRMaloneKMGuerandelAClinical examiners, simulated patients and student self-assessed empathy in medical students during a psychiatry Objective Structured Clinical ExaminationAcad Psychiatry201438445145724756942

- BergKBlattBLopreiatoJStandardised patients’ assessment of medical student empathy: ethnicity and gender in a multi-institutional studyAcad Med201590110511125558813

- BergKMajdenJFBergDVeloskiJHojatMMedical students self-reported empathy and simulated patients’assessment of student empathy: an analysis by gender and ethnicityAcad Med201186898498821694558

- SchwellerMCostaFOAntônioMAAmaralEMDe Carvalho-FilhoMAThe impact of simulated medical consultations on empathy levels of students at one medical schoolAcad Med201489463263724556779

- JohnstonJLLundyGMcCulloughMGormleyGJThe view from over there: reframing the OSCE through the experience of standardised patient ratesMed Educ201347989990923931539

- OgleJBushnellJACaputiAEmpathy is related to clinical competence in medical careMed Educ201347882483123837429

- LeeJZakiJHarveyPOOchsnerKGreenMFSchizophrenia patients are impaired in empathetic accuracyPsychol Med201141112297230421524334

- HojatMEmpathy in Patient Care: Antecedents, Development, Measurement, and OutcomesPhiladelphiaSpringer2007 Chapter 7

- FieldsSKMahanPTillmanPHarrisJMaxwellKHojatMMeasuring empathy in healthcare profession students using the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: healthcare provider – student versionJ Interprof Care201125428729321554061

- WardJSchaalMSullivanJReliability and validity of the Jefferson Scales of Physician Empathy in undergraduate nursing studentsJ Nurs Meas2009171738819902660

- ShashikumarRChaudharyRRyaliVSCross sectional assessment of empathy among undergraduates from a medical collegeMed J Armed Forces India201470217918524843209

- ShariatSVHabibiMEmpathy in Iranian medical students: measurement model of the Jefferson Scale of EmpathyMed Teach2013351e913e91822938682

- ParkKHRohHSunDHHojatMEmpathy in Korean medical students: findings from a nationwide surveyMed Teach2015371094394825182523

- DavisMHA multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathyJSAS Catalog Selected Documents Psychol19801085

- DavisMHMeasuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approachJ Pers Soc Psychol1983441113126

- LehmannABahcesularKBrockmannEMSubjective experience of emotions and emotional empathy in paranoid schizophreniaPsychiatry Res2014220382583325288043

- NarmePMourasHRousselMDuruCKrystowiakPGodefroyOEmotional and cognitive social processes are impaired in Parkinson’s disease and are related to behavioral disordersNeuropsychology201327218219223527646

- SchafferMClarkSJeglicELThe role of empathy and parenting style in the development of antisocial behaviorsCrime Delinq2009554586599

- Eberly-LewisMBCoetzeeTMDimensionality in adolescent prosocial tendencies: individual differences in serving others versus serving the selfPers Individ Dif20158216

- PartonFDayAEmpathy, intimacy, loneliness and locus of control in child sex offenders: a comparison between familial and non-familial child sexual offendersJ Child Sex Abus2002112415716221639

- KonrathSHO’BrienEHHsingCChanges in dispositional empathy in American college students over time: a meta-analysisPers Soc Psychol Rev201115218019820688954

- CostaPCarvalho-FilhoMSchwellerMMeasuring medical students’ empathy: exploring the underlying constructs of and associations between, two widely used self-report instruments in five countriesAcad Med2016

- HojatMGonnellaJSEleven years of data on the Jefferson Scale of Empathy-Medical Student Version JSE-S: proxy norm data and tentative cut-off scoresMed Princ Pract201524434435025924560

- BockEMHosserDEmpathy as a predictor of recidivism among young adult offendersPsychol Crime Law2014202101115

- HaidetPDainesJEPaternitiDAMedical student attitudes towards the doctor-patient relationshipMed Educ200236656857412047673

- HojatMMangioneSNascaTJAn empirical study of decline in empathy in medical schoolMed Educ200438993494115327674

- WoloschukPHarasymPHTempleWAttitude change during medical school: a cohort studyMed Educ200438552253415107086

- AustinEJEvansPMagnusBO’HanlonKA preliminary study of empathy, emotional intelligence and examination performance in MBChB studentsMed Educ200741768468917614889

- ChenDLewRHershmanWOrlanderJA cross-sectional measurement of medical student empathyJ Gen Intern Med200722101434143817653807

- YoussefFFNunesPSaBWilliamsSAn exploration of changes in cognitive and emotional empathy among medical students in the CaribbeanInt J Med Educ2014518519225341229

- MagalhãesESalgueiraAPCostaPCostaMJEmpathy in senior year and first year medical students: a cross-sectional studyBMC Med Educ2011115221801365

- RohMSHahmBJLeeDHEvaluation of empathy among Korean medical students: a cross-sectional study using the Korean version of the Jefferson Scale of Physician EmpathyTeach Learn Med201022316717120563934

- KakaokaHUKoideNOchiKHojatMGonnellaJSMeasurement of empathy among Japanese medical students: psychometrics and score differences by gender and level of medical educationAcad Med20098491192119719707056

- LeeBKBahnGHLeeWHParkJHYoonTYBaekSBThe relationship between empathy medical education system, grades and personality in medical college and medical schoolKorean J Med Educ200921211712425813109

- Rahimi-MadisehMTavakolMDennickRNasiriJEmpathy in Iranian medical students: a preliminary psychometric analysis and differences by gender and year of medical schoolMed Teach20103211e471e47821039088

- MostafaAHogueRMostafaMRangMMMostafaFEmpathy in undergraduate medical students of Bangladesh: psychometrics analysis and differences by gender, academic year and speciality preferencesISRN Psychiatry20142014375439

- TotoRLManLBlattBSimmensSJGreenbergLDo empathy, perspective-taking, sense of power and personality differ across undergraduate education and are they inter-related?Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract2015201233124677070

- BratekABulskaWBonkMSewerynMKrystaKEmpathy among physicians, medical students and candidatesPsychiatr Danub201527Suppl 1S48S5226417736

- ParoHBSilveiraPSPerottaBEmpathy among medical students: is there a relation with quality of life and burnout?PLoS One201494e9413324705887

- TavakolSDennickRTavakolMEmpathy in UK medical students: differences by gender, medical year and specialty interestEduc Prim Care201122529730322005486

- NeumannMEdlehäuserFTauschelDEmpathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residentsAcad Med2011868996100921670661

- RoffSReconsidering the “decline” of medical student empathy as reported in studies using the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy-Student version (JSPE-S)Med Teach2015378783786

- NewtonBWBarberLClardyJClevelandEO’SullivanPIs there hardening of the heart during medical school?Acad Med200883324424918316868

- WilliamsBSadasivanSKadirveluAMalaysian medical students self-report empathy: a cross-sectional comparative studyMed J Malaysia2015702768026162381

- HojatMVergareMJMaxwellKThe devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical schoolAcad Med20098491182119119707055

- KhademalhosseiniMKhademalhosseiniZMahmoodianFComparison of empathy among medical students in both basic sciences and clinical levelsJ Adv Med Educ Prof201422889125512926

- ChenDCKirshenbaumDSYanJKirshenbaumEAseltineRHCharacterizing changes in student empathy throughout medical schoolMed Teach201234430531122455699

- QuinceTAParkerRAWoodDFBensonJAStability of empathy among undergraduate medical students: a longitudinal study at one UK medical schoolBMC Med Educ2011119022026992

- ColliverJAConleeMJVerhulstSJDorseyJKReports of the decline of empathy during medical education are greatly exaggerated: a reexamination of the researchAcad Med201085458859320354372

- QuinceTAKinnersleyPHalesJEmpathy among undergraduate medical students: A multi-centre cross-sectional comparison of students beginning and approaching the end of their courseBMC Med Educ20161619226979078

- ZeOThomasPSuchanBCognitive and affective empathy in younger and older individualsAging Ment Health201418792993524827596

- MyyryLJuujärviSPessoKEmpathy, perspective taking and personal values as predictors of moral schemasJ Moral Educ2010392213233

- CoulterIDWilkesMDer-MartirosianCAltruism revisited: a comparison of medical, law and business students’ altruistic attitudesMed Educ200741434134517430278

- BlairRJResponding to the emotions of others: dissociating forms of empathy through the study of typical and psychiatric populationsConscious Cogn200514469871816157488

- van LangenMAMWissinkIBvan VugtESVan der StouweTStamsGJJMThe relationship between empathy and offending: a meta analysisAggress Violent Behav2014192179189

- WilbertzGBrakemeierELZobelIHärterMSchrammEExploring the preoperational features in chronic depressionJ Affect Disord2010124326226920089311

- CusiAMMacQueenGMSprengRNMcKinnonMCAltered empathetic responding in major depressive disorder: relation to symptom severity, illness burden and psychosocial outcomePsychiatry Res2011188223123621592584

- CusiAMacQueenGMMcKinnonMCAltered self-report empathetic responding in patients with bi-polar disorderPsychiatry Res2010178235435820483472

- HopeVHendersonMMedical student depression, anxiety and distress outside North America: a systematic reviewMed Educ2014481096397925200017

- DyrbyeLNThomasMRShanafeltTDA systematic review of depression, anxiety and other indicators of psychological distress among US and Canadian medical studentsAcad Med200681435437316565188

- BelliniLMSheaJAMood change and empathy decline persist during three years of internal medical trainingAcad Med200580216416715671323

- QuinceTAWoodDFParkerRABensonJPrevalence and persistence of depression among undergraduate medical students: a longitudinal study at one UK medical schoolBMJ Open201224e001519

- BrazeauCMShanafeltTDurningSJDistress among matriculating medical students relative to the general populationAcad Med201489111520152525250752

- DahlinMNilssonCStotzerERunesonBMental distress, alcohol use and help-seeking among medical and business students: a cross-sectional comparative studyBMC Med Educ2011119222059598

- BassolsAMOkabayashiLSSilvaABFirst and last year medical students: is there a differences in the prevalence and intensity of anxiety and depressive symptoms?Rev Bras Psiquiats2014363233240

- ChibnallJTTaitRCJovelAAccountability and empathy effects on medical students’ clinical judgments in a disability determination context for low back painJ Pain201415991592424952111

- LittlewoodSYpinazarVMargolisSAScherpbierASpencerJDornanTEarly practical experience and the social responsiveness of clinical education: systematic reviewBMJ2005331751338739116096306

- KrupatEPelletierSAlexanderEKHirshDOgurBSchwartzsteinRCan changes in the principal clinical year prevent the erosion of students’ patient-centred beliefs?Acad Med200984558258619704190

- SchwellerMde JorgeBSantosTMGrangeiaTdeAGde Carvalho-FilhoMADo it again! Medical students achieve higher empathy levels when exposed a simulated training with standardised patients more than oncePoster presented at: AMEE Conference2015Glasgow

- HaffertyFWBeyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculumAcad Med19987344034079580717

- WestCPShanafeltTDThe influence of personal and environmental factors on professionalism in medical educationBMC Med Educ200772917760986

- CaldicottCVFaber-LangendoenKDeception, discrimination and fear of reprisal: lessons in ethics from third year medical studentsAcad Med200580986687316123470

- BurgessAGoulstonKOatesKRole modelling of clinical tutors a focus group study among medical studentsBMC Med Educ2015151725888826

- Karnieli-MillerOVuTRFrankelRMWhich experiences in the hidden curriculum teach medical students about professionalism?Acad Med201186336937721248599

- BrownJHow clinical communication has become a core part of medical education in the UKMed Educ200842327127818275414

- StepienKABaernsteinAEducating for empathyJ Gen Intern Med200621552453016704404

- BrownJTransferring clinical communication skills from the classroom to the clinical environment: perceptions of a group of medical students in the United KingdomAcad Med20108561052105920505409

- BlattBLe LacheurSFGalinskyADSimmensSJGreenbergLDoes perspective taking increase patient satisfaction in medical encounters?Acad Med20108591445145220736672

- Fernández-OlanoCMontoya-FernándezJSalinas-SánchezASImpact of clinical interview training on empathy level of medical students and medical residentsMed Teach200830332232418509879

- DasGuptaSCharonRPersonal illness narratives: using reflective writing to teach empathyAcad Med200479435135615044169

- LimBTMoriartyHHuthwaiteM“Being in role”: a teaching innovation to enhance empathetic communication skills in medical studentsMed Teach20113312e663e66922225448

- MullenKNicolsonMCottonPImproving medical students’ attitudes towards the chronic sickBMC Med Educ2010108421092160

- Batt-RawdenSChisolmMSAntonBFlickingerTETeaching empathy to medical students: an updated systematic reviewAcad Med20138881171117723807099

- de SilvaDNo. 18. Measuring Patient ExperienceLondon, UKThe Health Foundation2013

- HegaziIWilsonIMaintaining empathy in medical school: it is possibleMed Teach201335121002100823782049

- ChoiDNishimuraTMotoiMEgashiraYMatsumotoRWatanukiSEffect of empathy trait on attention to various facial expressions: evidence from N170 and late positive potential (LPP)J Physiol Anthropol20143311824975115

- ChristopherGMcMurranMAlexithymia, empathic concern, goal management, and social problem solving in adult male prisonersPsychol Crime Law2009158697709