Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic inflammatory lung syndrome, caused by long-term inhalation of noxious gases and particles, which leads to gradual airflow limitation. All health care professionals who care for COPD patients should have full access to high-quality spirometry testing, as postbronchodilator spirometry constitutes the principal method of COPD diagnosis. One out of four smokers 45 years or older presenting respiratory symptoms in primary care, have non-fully reversible airflow limitation compatible with COPD and are mostly without a known diagnosis. Approximately 50.0%–98.3% of patients are undiagnosed worldwide. The majority of undiagnosed COPD patients are isolated at home, are in nursing or senior-assisted living facilities, or are present in oncology and cardiology clinics as patients with lung cancers and coronary artery disease. At this time, the prevalence and mortality of COPD subjects is increasing, rapidly among women who are more susceptible to risk factors. Since effective management strategies are currently available for all phenotypes of COPD, correctly performed and well-interpreted postbronchodilator spirometry is still an essential component of all approaches used. Simple educational training can substantially improve physicians’ knowledge relating to COPD diagnosis. Similarly, a physician inhaler education program can improve attitudes toward inhaler teaching and facilitate its implementation in routine clinical practices. Spirometry combined with inhaled technique education improves the ability of predominantly nonrespiratory physicians to correctly diagnose COPD, to adequately assess its severity, and to increase the percentage of correct COPD treatment used in a real-life setting.

Introduction

Definition

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common preventable and treatable disease, characterized by persistent airflow limitation, which is usually progressive and associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory response in the airways and the lung to noxious particles or gases. Exacerbations and comorbidities contribute to the overall severity in individual patients.Citation1 COPD is not a name of a single disease but an umbrella denomination used to describe chronic inflammatory lung syndrome, primarily caused by long-term harmful inhalation and leading to gradual airflow limitation – bronchial obstruction. The traditional medical terms chronic bronchitis and emphysema are now part of the COPD diagnosis, as most COPD subjects encountered in practice share both of these features.Citation1–Citation3 The most common symptoms of COPD are breathlessness with decreased physical activity and cough.Citation4,Citation5 COPD is not just a “smoker’s cough” but an underdiagnosed pulmonary disorder that may progressively lead to significant impairment of quality of life and premature death.Citation6

Prevalence of COPD

COPD constitutes a respiratory affliction of high prevalence with an explosively growing mortality and an immense global socioeconomic impact. The PLATINO study found that the prevalence of COPD in the population aged 40 years or older was 15.8%.Citation7 At the same time, 26% of adults with a prolonged (≥30 years) smoking history had been labeled as having COPD in South Carolina, US.Citation5 Recent studies estimated the COPD prevalence to be 5%–25%.Citation8,Citation9 General incidence of COPD varies widely from 1.5% to 11%.Citation10,Citation11 Epidemiological variability could be attributed to the different risk factors, genetic heterogeneity of population, and the criteria used for spirometry confirmation of COPD.Citation8,Citation12 The World Health Organization estimates COPD to become the third leading cause of death by 2030, and the burden of COPD is projected to further increase in the coming decades due to continued exposure to risk factors and aging of the global population.Citation6 Even though most of the information available on COPD prevalence, morbidity, and mortality comes from high-income countries, accurate epidemiologic data on COPD are difficult and expensive to collect. Nevertheless, the vast majority (90%) of estimated COPD deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries.Citation6 In the Czech Republic (with a population of >10.5 million), the recently estimated prevalence is 7%–8%; ~16,000 patients are hospitalized each year as a result of COPD, and >3,500 die annually.Citation13

Who is at risk?

In general, a strong genetic component in conjunction with an environmental insult accounts for the development of COPD. While the predominant risk factor is tobacco smoke (including passive smoke exposure), other factors such as age, a previous history of bronchial asthma, polygenetic predisposition, and frequent lower respiratory infections in childhood are significant.Citation1,Citation6 Environmental and occupational exposures to dusts and chemicals (such as vapors, irritants, and fumes) and household indoor biomass fumes also substantially contribute to the development of COPD, particularly in low-income countries. Fumes from biomass fuels used indoors by households account for the high prevalence of COPD in nonsmoking women in parts of the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia.Citation6 Globally, ~50% of all households and 90% of rural households use solid fuels (coal and biomass) as the main domestic source of energy, thus exposing ~50% of the world population, close to three billion people, to the harmful effects of these combustion products.Citation14 A fraction of COPD cases are attributable to work and are estimated as 19.2% overall and 31.1% among never smokers in the US population-based Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.Citation15 In the past, COPD was more common in men, but because of increased tobacco use among women in high-income countries, more prominent susceptibility to harmful components of tobacco smoke, and the higher risk of exposure to indoor biomass fuel in low-income countries, the disease currently affects men and women almost equally.Citation5,Citation6,Citation16

Problem of underrecognition of COPD

COPD diagnosis – why early?

COPD remains significantly underdiagnosed, with correct diagnosis commonly missed or delayed until the pulmonary impairment is advanced. Nonspecific clinical features of early disease are the main reason for this lag. A clinical diagnosis of COPD should be considered in any patient who has breathlessness, chronic cough or sputum production, and a history of exposure to risk factors for the disease.Citation1 Many patients have been labeled wrongly as simple “smokers” cough, repeated lower respiratory tract infections and/or asthma. However, it is contemplated that early diagnosis of COPD should have a positive impact on individual and population outcomes. Especially, earlier smoking cessation and avoiding other environmental and occupational risk factors before the devastating phase of COPD syndrome should be the critical point of successful management of all patients. Inhaled bronchodilators (BDs), regular physical activity, and other specific medical interventions are also able to favorably modify the natural course of early disease.Citation1,Citation3,Citation5

COPD diagnosis – spirometry

The cornerstone of the current approach to diagnosis of COPD lies within the evaluation of a patients’ lung functions, symptoms, history of exacerbations, and clinical phenotype assessment.Citation1,Citation17 Validity of the diagnosis should always be checked using spirometry. Spirometry is widely recommended as a screening method of all symptomatic individuals, especially in subjects with a long-term risk exposure.Citation18 The essential pathophysiological requirement for COPD diagnosis is the presence of a post-BD expiratory airflow limitation, which is defined, according to the current European Respiratory Society (ERS) statement, as a decrease in the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/vital capacity (VC) ratio below the lower limit of normal (LLN) values.Citation19,Citation20 Worldwide, the strategy of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) appointed the presence of post-BD FEV1/forced volume vital capacity (FVC) ratio <0.70 as an unsophisticated indicator of persistent airflow limitation – the most important pulmonary function feature of COPD subjects.Citation1 Globally, the spirometric criterion established by the GOLD is simple, independent of reference values, and has been used in numerous clinical trials. Diagnostic simplicity and consistency are key for the busy nonrespiratory specialist physicians. Nevertheless, ERS statement recommends use of the FEV1/VC ratio rather than just the FEV1/FVC ratio and the cut-off value of this ratio was set at the 5th percentile of the normal distribution (LLN) rather than at a fixed value of 0.7. The main advantage of using VC in place of FVC is that the ratio of FEV1 to VC is capable of accurately identifying more obstructive patterns than its ratio to FVC, because FVC is more dependent on flow and volume histories. In contrast with a fixed value of 0.7, the use of the 5th percentile (LNN) does not lead to an overestimation of the ventilatory defect in older people (males aged more than 40 and females aged more than 50 years) with no history of exposure to noxious particles or gases.Citation1,Citation19,Citation20 The above-mentioned LLN values are based on the normal distribution and classify the bottom 5% of the healthy population as abnormal (below LLN). However, the LLN values are highly dependent on the choice of valid reference equations. Currently, we would propose the use of GOLD approach in general practices and ERS recommendations in practices of pulmonary specialists.Citation1,Citation18–Citation20

COPD diagnosis – exacerbation history

The most common clinical presentations of COPD are dyspnea, cough, fatigue, and intolerance of physical activity.Citation21–Citation25 Dyspnea first occurs during high-intensity activities, subsequently during low-intensity movements, and later even at rest. Breathlessness slowly induces gradual exercise intolerance resulting in physical inactivity, significant life style change, and social isolation of COPD patients.Citation25 COPD patients commonly experience a cough, which can be productive in approximately two-thirds of cases or nonproductive.Citation26 Long-lasting cough may adversely affect performance in daily life due to its negative effect on fatigue and decrease abdominal muscle endurance in patients with COPD.Citation27 The progressive course of COPD could be complicated by episodes of acute worsening called exacerbations, in 25%–40% of subjects.Citation1,Citation28 Although most guidelines and clinical trials define COPD exacerbations similarly, there are differences in the exact definition used. Most of them use event-based description of exacerbation, which necessitates an increase in both symptoms and the use of health care resources, and grade exacerbations based on their severity, ie, moderate exacerbations as those requiring treatment with systemic corticosteroids and/or antibiotics and severe exacerbations as those necessitating admission to the hospital.Citation29,Citation30 The ERS and the American Thoracic Society task force group simply defined exacerbation as an increase in respiratory symptoms over baseline that usually lead to a change in treatment.Citation31

COPD diagnosis – symptoms

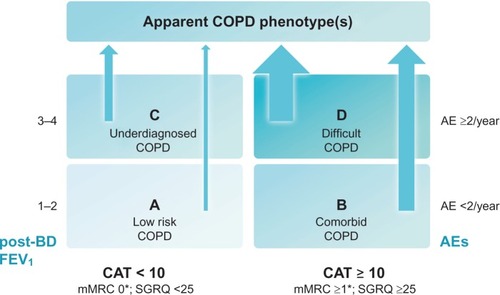

In addition to expiratory airflow limitation quantification and careful taking of exacerbation history, it is recommended to measure COPD symptoms universally, using the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) and/or the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale.Citation1,Citation32 Using three (airflow limitation, exacerbation frequency and symptoms) parameters, it is possible to classify each patient into one of the four categories denoted A, B, C, and D according to the latest version of GOLD.Citation1,Citation33 Cutoff points of mMRC grade ≥2 and CAT score ≥10 were initially established by GOLD as equivalents in determining patients with high symptomatology (GOLD). Category A represents the early stages of the disease. The elimination of all inhalation risks could fundamentally change the prognosis of patients in category A and reduce the overall burden caused by COPD.Citation34,Citation35 Category B deserves particular attention as it consists of highly symptomatic patients with a less pronounced lung function deterioration, although they have a significantly higher mortality risk – mainly cardiovascular and malignant causes or the severity of lung emphysema does not strictly correspond to FEV1.Citation36–Citation38 Patients with low symptomatology level make up the category C. They can usually be found in the general population, but rarely in the pulmonologist’s care. This group of patients can be a smart target for active screening programs, such as category A.Citation39 Mortality risk of C patients is moderate or low (significantly lower than in those in the B category).Citation36,Citation37 The highest mortality risk is associated with the D category, especially if the classification is made on the basis of frequent exacerbations.Citation40 D subjects are extremely threatened by high respiratory and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality rates; therefore, careful monitoring and treatment of these individuals in the hands of respiratory specialists has to be thorough and comprehensive in every aspect.Citation36 Long-term variability of the patient’s GOLD classification strongly corresponds with the changes in CAT scores.Citation41 The GOLD classification does well in identifying individuals at risk of exacerbations, although the predictive ability for mortality in elderly adults with COPD is not high.Citation37 Unfortunately, clinical equivalence of GOLD-proposed symptom’s borders between both low and high symptomatic subjects (mMRC scale ≥2= CAT score ≥10) seems to be problematic.Citation42 Therefore, possible recalibration of symptom equivalence, and new threshold for COPD symptom assessment (eg, mMRC scale ≥1= CAT score ≥10 and mMRC scale ≥2= CAT score ≥17), could improve the validity of GOLD categories.Citation43 In accordance with data published in 2013 by Jones et al, the Czech Pneumological and Phthisiological Society (CPPS) recommends the use of assessment of these respiratory symptoms with a slight modification of GOLD ().Citation42,Citation44

Figure 1 GOLD A–D categories with slight modification of the Czech Pneumological and Phthisiological Society.

Abbreviations: AE, acute exacerbation; BD, bronchodilator; CAT, COPD Assessment Test; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; SGRQ, St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire.

COPD diagnosis – phenotypical heterogeneity

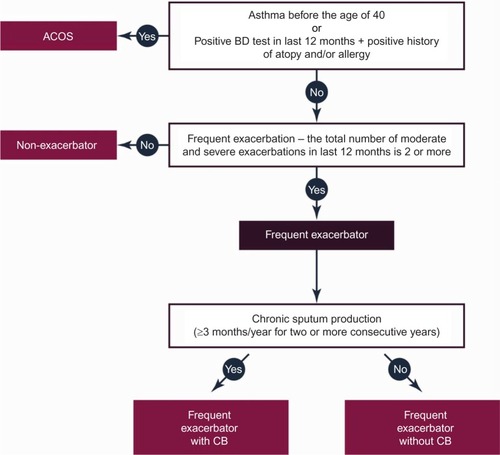

COPD is a well-known heterogeneous condition with multiple clinical faces.Citation1,Citation2 Simplifications cannot express the myriad of forms of this serious syndrome.Citation45–Citation47 GOLD documents current new innovations in the approach to treating COPD and provides the right steps toward individualized care of COPD patients.Citation1 However, physicians worldwide feel that the clinical variety of this disease greatly exceeds the two-dimensional diagram of dividing the patients into four A–D categories (). Each patient is unique.Citation8,Citation48 Moreover, GOLD is not designed to be a guideline but to be a strategy or the minimal global diagnosis and treatment requirements. Therefore, it is of no surprise that a number of different countries have published their own national recommendations, sometimes based on the GOLD principles, reflecting the specific local needs and possibilities ().Citation17,Citation49–Citation54 The heterogeneity of COPD can lead to phenotype categorization because not all patients respond to all types of treatments. In terms of treatment, phenotypes were first used in the Spanish COPD recommendations.Citation17 The Spanish COPD guidelines (La Guía Española de la EPOC [GesEPOC]) divided COPD into the following four clinically defined groups: infrequent exacerbators, asthma and COPD overlap syndrome (ACOS), frequent exacerbators with a predominance of chronic bronchitis, and frequent exacerbators without the presence of chronic bronchitis (). The most controversial variant of COPD is ACOS. The ACOS has been defined as symptoms of increased reversibility of airflow limitation, more eosinophilic bronchial and systemic inflammation, and increased response to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), compared with the remaining COPD subjects. ACOS patients have more frequent exacerbations, more wheezing and dyspnea, and more intensive health status impairment.Citation49,Citation55 The influence of the GesEPOC’s guidelines on other national documents is indisputable.Citation17,Citation48,Citation49,Citation55 Although this phenotypically targeted approach to COPD subjects is still not widely accepted, the idea of phenotypes has already been adopted by some authors.Citation56 However, there is no great consensus on the number of phenotypes and their precise definition; the number can be anywhere from two to 210 million, which is the estimated number of COPD patients worldwide.Citation8

Figure 2 Simplified clinical definition of COPD phenotypes proposed by Marc Miravitlles, which is used in the POPE Study.

Abbreviations: ACOS, asthma and COPD overlap syndrome; BD, bronchodilator; CB, chronic bronchitis; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; POPE Study, phenotypes of COPD in Central and Eastern Europe study.

Table 1 Short summary of several recent COPD guidelines

COPD underdiagnosis and undertreatment

The real prevalence of COPD is higher than the number of actively assessed and treated COPD subjects, and most COPD individuals still remain undiagnosed and untreated in all parts of the world.Citation1 In contrast, a small fraction of subjects labeled and treated as having COPD do not have any spirometry confirmation of this condition (). Recently, Llordés et al have performed a population-based, epidemiological study, conducted in a primary care setting among subjects older than 45 years with a positive history of smoking. A total of 1,738 individuals (84.4% males) with a mean age of 59.9 years took part. The prevalence of COPD was 24.3%, with an overall underdiagnosis of 56.7%. Generally, patients with COPD were older, more frequently male, with a lower body mass index, a longer history of smoking, lower educational level, occupational exposure in history, and more cardiovascular comorbidities. On the other hand, 15.6% of individuals with a diagnosis of COPD did not have any airflow obstruction pattern; they were misdiagnosed as having COPD.Citation57 Similar results are apparent in the analysis published by Lamprecht et al from the BOLD Collaborative Research Group, the EPI-SCAN Team, the PLATINO Team, and the PREPOCOL Study Group. Among 30,874 participants (mean age 56 years, 55.8% females, 22.9% current smokers), there existed varied population prevalence of COPD from 3.6% in Colombia to 19.0% in South Africa. Globally, 81.4% of COPD cases confirmed by a spirometry were previously undiagnosed. There were significant differences between countries: 50.0% of under-diagnosed individuals in the US versus 98.3% of underdiagnosed subjects in Nigeria (). A greater chance of being undiagnosed with COPD was found in the male sex and those with younger age, never and current smoking, lower level of education, less severe airflow limitation, and absence of spirometry in the medical history.Citation58 Community pharmacologists have easy access to potentially undiagnosed COPD individuals. In the population of 1,456 Spanish subjects identified as having “high risk” from COPD (with three or more “yes” replies to GOLD-proposed questionnaire: a) older than 40 years; b) smoker/ex-smoker; c) more breathlessness than peers of the same age; d) chronic cough; and e) chronic expectoration), the presence of pre-BD airflow limitation in 282 (19.8%) of them was confirmed. These data were obtained through cross-sectional, descriptive, uncontrolled, remotely supported study in 100 community pharmacologist workplaces in Barcelona, Spain.Citation59

Table 2 Underdiagnosis of COPD

Zhang et al showed that underdiagnosis and undertreatment of COPD remain quite common in lung cancer patients. Medical records of hospitalized lung cancer patients in Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (general teaching hospital in the east coast of the People’s Republic of China), were retrospectively reviewed between January 2006 and December 2010. The prevalence of spirometry-defined COPD in hospitalized individuals with lung cancer was 21.6% (705/3,263). Out of these 705 patients, only 50 (7.1%) were previously diagnosed as having COPD, while 655 (92.9%) were undiagnosed. Smoking history (10.3% vs 1.5%) and presence of respiratory symptoms (24.8% vs 2.2%) promote correct COPD diagnosis.Citation60 Moreover, many COPD exacerbations go unreported and untreated.Citation61,Citation62 Electronic symptom diaries or the EXAcerbations of Chronic pulmonary disease Tool (EXACT) scale can be used to detect such undiagnosed events, using definitions that depend on a sustained worsening of respiratory symptoms for 2 consecutive days.Citation63,Citation64

Difficulty diagnosing COPD

Where are the missing COPD patients?

Comparisons with age-matched population data showed that people with COPD spend extended periods in sedentary behaviors, have limited engagement in physical activity (walking and exercising), have high health care needs (medical appointments), and experience difficulties associated with activities of daily living (personal self-care and chores) compared to non-COPD subjects in the similar age. The majority of undiagnosed COPD patients are at home, without intensive social contact; often in nursing homes; or at senior-assisted living facilities.Citation65

Potentially promising “sources” of new, still undiagnosed, COPD subjects can be oncology and cardiology clinics caring for subjects with lung cancers and coronary artery disease (CAD). As mentioned earlier, Chinese colleagues retrospectively confirmed the presence of COPD in almost 22% of subjects being treated for pulmonary malignancy; a notable part of them (93%) were not previously diagnosed.Citation60 The Spanish group (Almagro et al) has recently published the first robust prospective study related to this issue. They consecutively examined 133 patients after percutaneous coronary intervention due to CAD (63.0 years). One month after percutaneous coronary intervention, 24.8% of them met spirometry criteria for COPD, of whom 81.8% were undiagnosed. CAD subjects with COPD were older, had more coronary vessels affected, and had a greater history of previous myocardial infarction. Subsequent follow-up (median 934 days) confirmed poor prognostic impact of COPD on all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 8.85) and cardiovascular morbidity (HR 1.87). These differences remained after adjustment for sex, age, number of coronary vessels affected, and previous myocardial infarct.Citation66

Finally, possible source of new cases can be found in patients examined by computed tomography (CT) of the thorax. Incidental CT findings of emphysema and airway thickening, as seen on routine diagnostic chest CT scans performed for several nonpulmonary clinical indications, are associated with future severe exacerbations of COPD resulting in hospitalization or death. This statement was fully confirmed by a large multicentre prospective case–cohort study comprising 6,406 subjects who underwent routine diagnostic chest CT for nonpulmonary indications, published recently by PROVIDI Study group. Using a case–cohort approach was visually graded CT scans from cases and a random sample of ∼10% of the baseline cohort (n=704) for emphysema severity (range 0–20), airway thickening (range 0–5), and bronchiectasis (range 0–5). During a median follow-up of 4.4 years, 338 of COPD events were identified. The risk of experiencing a future acute exacerbation of COPD resulting in hospitalization or death was significantly increased in subjects with severe emphysema (score ≥7) and severe airway thickening (score ≥3). The respective HRs were 4.6 and 5.9. Severe bronchiectasis (score ≥3) was not significantly associated with increased risk of adverse events (HR 1.5). Morphological correlates of COPD such as emphysema and airway thickening detected on routine CT scans obtained for other nonpulmonary indications are strong independent predictors of subsequent development of acute exacerbations of COPD resulting in hospitalization or death.Citation67

Why do we have problems with correct diagnosis of elderly COPD patients?

The prevalence of COPD dramatically increases with age (global median age of patients reaches 65–67 years), and COPD complicated by chronic respiratory failure may be considered as a frequent geriatric condition. Unfortunately, most clinical cases in the elderly remain undiagnosed because of: a) atypical clinical presentation; b) symptoms overlapping due to coexistence of COPD and other prominent comorbidities; and c) difficulty with respiratory function evaluation of seniors (spirometry needs a high level of adherence and activity of all examined subjects). Logically, the disease is commonly unrecognized and undertreated. This is expected to noticeably impact the health status of unrecognized COPD patients because a timely therapy could mitigate the distinctive and important effects of COPD on the health status. Besides having major prognostic implications, comorbidities also play a pivotal role in conditioning both the health status and the therapy of COPD. Several problems affect the overall quality of therapy for the elderly with COPD, and current guidelines as well as results from pharmacological trials only to some extent apply to these patients. Finally, physicians of different specialties care for the elderly COPD patient: physicians’ specialties largely determine the approach to differential diagnosis.

As such, COPD, in itself a syndrome, becomes difficult to diagnose and to manage in the elderly. Interdisciplinary efforts are desirable to provide the practicing physician with a multidisciplinary guide to the identification and treatment of COPD.Citation1,Citation68

Physician’s training in diagnosing COPD – ability to carry out spirometry

Educated physicians (especially, pulmonary specialists) are able to distinctly improve appropriate diagnosis of COPD. The correct diagnosis of COPD subjects among respiratory specialists (34.8%) was significantly higher than in nonrespiratory physicians (2.9%) in the recent Chinese study.Citation60 The 1-hour training course and a spirometry evaluation could increase the ability of a nonrespiratory physician to correctly diagnose and treat COPD patients. This statement was clearly confirmed by a recent study of Cai et al from the Hunan province in the South Central People’s Republic of China. A total of 225 internists worked at eight secondary hospitals, which previously did not have spirometry technology available, and underwent a 1-hour training session on the Chinese COPD guidelines. The mean scores of COPD knowledge (out of 100) before and after the training course were 53.1±21.7 and 93.3±9.8, respectively. Subsequently, 18 internists and 307 patients without a COPD diagnosis participated in the spirometry intervention. Based on the spirometry results, the prevalence of COPD was 38.8%. Nonrespiratory physicians (after 1-hour training) correctly identified the presence of COPD without spirometry data in 76.6% cases; this increased to 97.4% cases once spirometry data were available. Spirometry data also significantly improved the ability of physicians to correctly grade COPD severity. In the 119 patients who were determined by spirometry to have COPD, treatments prescribed to patients before nonrespiratory physicians were given spirometry results were compared to treatments prescribed after the results were made available. Based on the recommendations of GOLD and the Chinese COPD guidelines, the percentage of correct COPD treatment prescribed improved from 18.5% (22/119) to 84.0% (100/119). The changes in prescriptive patterns were most evident in the groups of patients with moderate and severe COPD.Citation69

It was shown that adequately trained and supported community pharmacists (4-day interactive training focused on spirometry and web assistance) can effectively identify individuals at high risk of having COPD, and thereafter, they can perform spirometry evaluation of this high-risk cohort. Good quality, clinically acceptable pre-BD spirometries were captured in 69.4% of the cases.Citation59

Physician’s awareness of diagnostic and treatment guidelines and the role of Continuing Medical Education

Real-life implementation of guidelines in the COPD field

The best available evidence-based guidelines can improve the positive clinical impact of COPD management. Identifying the target audience, deciding what type of evidence to include, and establishing, reporting, and publishing guidelines are only the initial steps. Educational activity and disseminating, implementing, evaluating, and updating these guideline documents are the necessary next steps toward routine medical application.Citation70 We did not know if COPD-related guidelines and recommendations are adequately a) explained and b) followed by respiratory physicians and general practitioners (GPs) around the globe. Two multicentre, cross-sectional studies, related to understanding of self-reported COPD guidelines and translation of this knowledge into routine practice, were performed in the Czech Republic. In this country (like in Slovakia, Hungary, or Serbia), COPD patients are predominantly cared for by respiratory physicians (95% of COPD subjects) and a minority of COPD individuals (up to 5%) are in the GP’s care.Citation54 The primary objective of the first study (conducted in 2012) was to examine the extent to which GOLD 2011 was used among Czech respiratory specialists, in particular with regard to the correct A–D classification of their COPD patients. The secondary objective was to explore what effect an erroneous classification has on the inadequate use of ICS. Based on 1,355 patient electronic forms, a discrepancy between the subjective and objective classifications was found in 32.8% of cases. The most common reason for incorrect classification was an error in the assessment of symptoms, which resulted in underestimation in 23.9% of cases and overestimation in 8.9% of the patients’ records examined. The specialists seeing >120 patients/month were most likely to misclassify their condition and were found to have done so in 36.7% of all patients seen. While examining the subjectively driven ICS prescription, it was found that 19.5% of patients received ICS not according to guideline recommendations, while in 12.2% of cases, the ICS were omitted, contrary to guideline recommendations. It was therefore concluded that Czech pulmonary specialists tend to either underprescribe or overuse ICS. Women were overprescribed ICS more frequently than men.Citation39 Similar to Czech results, Sarc et al reported that overprescription of ICS reached 25%.Citation71 Overtreatment with ICS has also been reported elsewhere.Citation72–Citation74

In May 2013, the CPPS published the new national guidelines based on the simultaneous use of GOLD principles and COPD phenotypes (). The implementation rate of this innovative approach into the routine practice of respiratory specialists was the main purpose of the second study (with similar design and respondent cohort) 2 years ago. The data regarding 1,323 consecutive COPD subjects (413 males, FEV1 52.6%, 18.3% nonsmokers) from 86 pulmonary specialists were obtained (half of them from nonhospital services, 17% from university hospitals). Twenty-three percent of all Czech respiratory physicians, from all the 14 districts of the Czech Republic took part. The majority declared routine use of GOLD categories and clinical phenotypes as well. Simple clinical assessment of COPD phenotypes showed 16.2% ACOS subjects, 62.3% nonexcerbators, and 18.4% and 3.2% exacerbators with and without bronchitis. More sophisticated procedure used on 409 participants (with recent CT available) found pulmonary emphysema in 65.4% and COPD-associated bronchiectasis (bronchiectasis–COPD overlap syndrome) in 15.7%. One-third of the patients had two or more phenotypical labels. Long-term therapy of COPD consisted of long-acting β2-agonists 75.9%, long-acting muscarinic antagonists 57.5%, ICS 46.2%, theophyllines 45.7%, mucoactive drugs 15.7%, roflumilast 8.3%, and antibiotics 1%. One year later, the Czech doctors found classification according to GOLD criteria slightly more preferable rather than by phenotypes when prescribing ICS, roflumilast, and mucoactive drugs. Approximately half of the patients (49%–58%) had their medication prescribed correctly both by GOLD and phenotypes. The self-reported acknowledgment of the phenotypically centered CPPS guidelines among specialists was satisfactory. Despite high awareness of the new guidelines, the real-life implementation was insufficient as treatment habits did not fully reflect the phenotypical approach.Citation13

Role of Continuing Medical Education and successful strategies in training of health care providers

GPs as the first-line physicians provide care for the vast majority of COPD individuals in both the developed and developing countries. Despite the availability of clinical practice guidelines for COPD, their influence on daily practice is unclear. A study in Birmingham, AL, USA, focused on examination of primary care decision-making, perceptions, and educational needs relating to COPD. In all, 784 practicing GPs were used in the analysis. On average, physicians estimated that 12% of their patients had COPD. Although 55% of physicians were aware of major COPD guidelines, only 25% used them to guide decision-making. Self-identified guidelines showed that users of Continuing Medical Education (CME) guidelines were more likely to order spirometry for subtle respiratory symptoms (74% vs 63%) to initiate therapy for mild symptoms (86% vs 77%) and to choose long-acting BDs for persistent dyspnea associated with COPD (50% vs 32%).Citation76

Eastern European countries have two most important nonmalignant chronic diseases responsible for the majority of death: congestive heart failure and COPD. Peabody et al published a national assessment of the quality of clinical care practice in the Ukrainian health care system.

In all, 136 hospitals and 125 outpatient settings were surveyed; 1,044 physicians were interviewed and completed clinical performance and value vignettes. On average, physicians scored 47.4% on the vignettes. Younger, female physicians provide a higher quality of care, as well as those who have completed the recent CME program. Higher quality of care was associated with significantly better health outcomes.Citation77

In addition, optimal management of COPD subjects depends on adherence to multiple devices used for inhaled medications. The critical errors committed during inhaler use can reduce treatment effectiveness. Outpatient education in inhaler technique remains widely inconsistent due to: a) time- consuming character of careful inhalation training; b) limited resources; and c) inadequate health care provider’s knowledge.Citation78 To determine whether a simple, two-session inhaler education program can improve physician attitudes toward inhaler education in primary care practice, a small-group hands-on device training session for GPs in British Columbia and Alberta was arranged. Sessions were spaced 1–3 months apart. All critical errors were corrected in the first session. Before the program, only 49% of GPs reported providing some form of inhaler use education in their practices and only 10% felt fully competent to teach patients inhaler technique. After the program, 98% rated their inhaler teaching as good to excellent. All stated that they could teach inhaler technique within 5 minutes. Observation of GPs during the second session by certified respiratory educators found that none made critical errors and all had excellent technique.Citation79

Future prospects/conclusion

COPD is still a widely underdiagnosed and undertreated pulmonary condition. The routine use of quality spirometry in primary care in subjects with respiratory symptoms should reduce underdiagnosis of COPD.Citation82 More comprehensive spread of health care professionals’ education and correct use and adequate interpretation of spirometry assessment could reduce the incidence of undiagnosed cases, particularly in smoking women, elderly subjects, and individuals being treated for lung cancer, CAD, heart failure, and diabetes. A number of studies have evaluated the accuracy of screening tests for COPD in primary care. The results of systematic review and meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of screening tests for COPD confirmed by spirometry among individuals aged ≥35 years with no prior diagnosis of COPD were presented. Bivariate meta-analysis of sensitivity and specificity was performed. Ten studies were included. Eight assessed screening questionnaires (the COPD Diagnostic Questionnaire [CDQ] was the most evaluated), four assessed handheld flow meters (COPD-6), and one assessed their combination. Among ever smokers, the CDQ had a pooled sensitivity of 64.5% and a specificity of 65.2%, and handheld flow meters had a sensitivity of 79.9% and a specificity of 84.4%. Handheld flow meters demonstrated higher test accuracy than the CDQ for COPD screening in primary care. The choice of alternative screening tests within whole screening programs should now be fully evaluated in future better designed studies.Citation80

More research on strategies to reduce the overwhelming phenomenon of COPD underdiagnosis is needed. COPD underdiagnosis has remained high in many countries, even after years of multiple interventions.Citation58 Apart from primary care as the central venue to screen for COPD, other options might be considered, such as community pharmacists trained in spirometry or active searching for COPD associated with the presence of comorbid disease (lung cancer, CAD, heart failure, and diabetes).Citation59,Citation66–Citation68

The Finnish National Prevention and Treatment Program for Chronic Bronchitis and COPD is an example of a good approach and new strategy in finding COPD. It includes the widespread (not only elderly males with smoking history) use of spirometry testing combined with smoking cessation efforts.Citation81

Practice guidelines and CME programs have not yet adequately reached many physicians. Because guidelines appear to influence clinical decision-making, efforts to propagate them more broadly are needed. Future CME education should present diagnostic algorithms tailored to both primary care settings and specialists, assess and strengthen spirometry interpretation skills, and discuss a reasoned approach to treatment strategy. Internet-based CME formats may be useful for reaching physicians in many areas.

Disclosure

VK presented the lectures at symposia, was sponsored by, and received fees for advisory board participation and travel grants from AstraZeneca, Berlin-Chemie, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Medicom, Mundipharma, Novartis, and Takeda. He received research grants from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim and Novartis. BN, ZZ, and KH are employees of the Institute of Biostatistics and Analyses, Masaryk University. The Institute of Biostatistics and Analyses has received research grants from (in alphabetical order) AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [webpage on the Internet]Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease [updated January, 2014] Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report_2014_Jun11.pdfAccessed September 30, 2015

- AnonCTerminology, definitions, and classification of chronic pulmonary emphysema and related conditions: a report of the conclusions of a Ciba guest symposiumThorax195914286299

- CorhayJLPersonalized medicine: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treatmentRev Med Liege2015705–631031526285458

- AnderssonMStridsmanCRönmarkELindbergAEmtnerMPhysical activity and fatigue in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – a population based studyRespir Med201510981048105726070272

- LiuYPleasantsRCroftJSmoking duration, respiratory symptoms, and COPD in adults aged ≥45 years with a smoking historyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015101409141626229460

- World Health Organisation [webpage on the Internet]Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) [updated October, 2013] Available from: http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/en/Accessed August 2, 2015

- MenezesAMJardimJRPérez-PadillaRPrevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and associated factors: the PLA-TINO Study in Sao Paulo, BrazilCad Saude Publica20052151565157316158163

- RycroftCEHeyesALanzaLBeckerKEpidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a literature reviewInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2012745749422927753

- BuistASMcBurnieMAVollmerWMBOLD Collaborative Research GroupInternational variation in the prevalence of COPD (the BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence studyLancet2007370958974175017765523

- KojimaSSakakibaraHMotaniSIncidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and the relationship between age and smoking in a Japanese populationJ Epidemiol2007172546017420613

- de MarcoRAccordiniSMarconAEuropean Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS)Risk factors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a European cohort of young adultsAm J Respir Crit Care Med2011183789189720935112

- MoreiraGLGazzottiMRManzanoBMIncidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease based on three spirometric diagnostic criteria in Sao Paulo, Brazil: a nine-year follow-up since the PLATINO prevalence studySao Paulo Med J2015133324525126176929

- KoblizekVZigmondJPecenLImplementation of COPD Phenotypes in Real LifeThematic Poster Session. European Respiratory Society Congress 2015Amsterdam, the Netherlands

- Torres-DuqueCMaldonadoDPérez-PadillaRForum of International Respiratory Studies (FIRS) Task Force on Health Effects of Biomass ExposureBiomass fuels and respiratory diseases: a review of the evidenceProc Am Thorac Soc20085557759018625750

- HnizdoESullivanPABangKMWagnerGAssociation between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and employment by industry and occupation in the US population: a study of data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyAm J Epidemiol2002156873874612370162

- AryalSDiaz-GuzmanEManninoDMInfluence of sex on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk and treatment outcomesInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201491145115425342899

- MiravitllesMSoler-CataluñaJJCalleMSpanish guideline for COPD (GesEPOC). Update 2014Arch Bronconeumol201450suppl 111624507959

- QaseemAWiltTJWeinbergerSEAmerican College of PhysiciansAmerican College of Chest PhysiciansAmerican Thoracic SocietyEuropean Respiratory SocietyDiagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory SocietyAnn Intern Med2011155317919121810710

- MillerMRHankinsonJBrusascoVATS/ERS Task ForceStandardisation of spirometryEur Respir J200526231933816055882

- PellegrinoRViegiGBrusascoVInterpretative strategies for lung function testsEur Respir J200526594896816264058

- CelliBCoteCMarinJThe body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med20043501005101214999112

- CelliBUpdate on the management of COPDChest20081331451146218574288

- O’DonnellDFlügeTGerkenFEffects of tiotropium on lung hyperinflation, dyspnoea and exercise tolerance in COPDEur Respir J20042383284015218994

- StridsmanCLindbergASkärLFatigue in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a qualitative study of people’s experiencesScand J Caring Sci20142813013823517049

- KarpmanCBenzoRGait speed as a measure of functional status in COPD patientsInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201491315132025473277

- KoblizekVTomsovaMCermakovaEImpairment of nasal mucociliary clearance in former smokers with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease relates to the presence of a chronic bronchitis phenotypeRhinology20114939740621991564

- ArikanHSavciSCalik-KutukcuEThe relationship between cough-specific quality of life and abdominal muscle endurance, fatigue, and depression in patients with COPDInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015101829183526379433

- MatkovicZMiravitllesMChronic bronchial infection in COPD. Is there an infective phenotype?Respir Med20131071102223218452

- HurstJRVestboJAnzuetoAEvaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) InvestigatorsSusceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseN Engl J Med20103631128113820843247

- WiseRAAnzuetoACottonDTIOSPIR InvestigatorsTiotropium Respimat inhaler and the risk of death in COPDN Engl J Med20133691491150123992515

- CazzolaMMacNeeWMartinezFJAmerican Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society Task Force on outcomes of COPDOutcomes for COPD pharmacological trials: from lung function to biomarkersEur Respir J20083141646918238951

- MolenTMiravitllesMKocksJCOPD management: role of symptom assessment in routine clinical practiceInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2013846147124143085

- HanMMuellerovaHCurran-EverettDGOLD 2011 disease severity classification in COPDGene: a prospective cohort studyLancet Respir Med20131435024321803

- YawnBDuvallKPeabodyJThe impact of screening tools on diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary careAm J Prev Med20144756357525241196

- JonesRPriceDRyanDRespiratory Effectiveness GroupOpportunities to diagnose chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in routine care in the UK: a retrospective study of a clinical cohortLancet Respir Med2014226727624717623

- LangePMarottJVestboJPrediction of the clinical course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, using the new GOLD classification: a study of the general populationAm J Respir Crit Care Med201218697598122997207

- ChenCZOuCYYuCHYangSCChangHYHsiueTRComparison of global initiative for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2013 classification and body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exacerbations index in predicting mortality and exacerbations in elderly adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Am Geriatr Soc20156324425025641518

- Sanchez-SalcedoPBertoJde-TorresJLung cancer screening: fourteen year experience of the Pamplona early detection program (P-IELCAP)Arch Bronconeumol201551416917625641356

- KoblizekVPecenLZatloukalJReal-life GOLD 2011 implementation: the management of COPD lacks correct classification and adequate treatmentPLoS One20149e11107825380287

- McGarveyLLeeAJRobertsJGruffydd-JonesKMcKnightEHaughneyJCharacterisation of the frequent exacerbator phenotype in COPD patients in a large UK primary care populationRespir Med201510922823725613107

- CasanovaCMarinJMartinez-GonzalezCCOPD History Assessment In SpaiN (CHAIN) Cohort. New GOLD classification: longitudinal data on group assignmentRespir Res201415324417879

- JonesPAdamekLNadeauGBanikNComparisons of health status scores with MRC grades in a primary care COPD population: implications for the new GOLD 2011 classificationEur Respir J20134264765423258783

- CasanovaCMarinJMMartinez-GonzalezCCOPD History Assessment in Spain (CHAIN) Cohort Differential effect of modified medical research council dyspnea, COPD assessment test, and clinical COPD questionnaire for symptoms evaluation within the new GOLD staging and mortality in COPDChest2015148115916825612228

- KoblizekVChlumskyJZindrVGOLD and Phenotypes: The New Czech COPD Guidelines. Thematic Poster SessionEuropean Respiratory Society Congress2015Amsterdam, the Netherlands

- BakkePRönmarkEEaganTRecommendations for epidemiological studies on COPDEur Respir J2011381261127722130763

- AgustiAThe path to personalised medicine in COPDThorax20146985786424781218

- VestboJCOPD: definition and phenotypesClin Chest Med2014351624507832

- Izquierdo-AlonsoJRodriguez-GonzálezmoroJde Lucas-RamosPPrevalence and characteristics of three clinical phenotypes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)Respir Med201310772473123419828

- MiravitllesMCalleMSoler-CataluñaJClinical phenotypes of COPD. Identification, definition and implications for guidelinesArch Bronconeumol201248869822196477

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [webpage on the Internet]Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (updated) Clinical Guidelines CG101 Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/CG101Accessed February 19, 2015

- KankaanrantaHHarjuTKilpeläinenMDiagnosis and pharmacotherapy of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the finnish guidelinesBasic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol201511629130725515181

- GuptaDAgarwalRAggarwalAS. K. Jindal for the COPD Guidelines Working Group. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: joint ICS/NCCP (I) recommendationsLung India20133022826724049265

- KhanJLababidiHAl-MoamaryMThe Saudi guidelines for the diagnosis and management of COPDAnn Thorac Med20149557624791168

- KoblizekVChlumskyJZindrVCzech Pneumological and Phthisiological SocietyChronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: official diagnosis and treatment guidelines of the Czech Pneumological and Phthisiological Society; a novel phenotypic approach to COPD with patient-oriented careBiomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub201315718920123733084

- Soler-CataluñaJCosíoBIzquierdoJConsensus document on the overlap phenotype COPD-asthma in COPDArch Bronconeumol20124833133722341911

- MontuschiPMalerbaMSantiniGMiravitllesMPharmacological treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: from evidence-based medicine to phenotypingDrug Discov Today2014191928193525182512

- LlordésMJaénAAlmagroPPrevalence, risk factors and diagnostic accuracy of COPD among smokers in primary careCOPD201512440441225474184

- LamprechtBSorianoJStudnickaMBOLD Collaborative Research Group, the EPI-SCAN Team, the PLATINO Team, and the PREPOCOL Study GroupBOLD Collaborative Research Group the EPI-SCAN Team the PLATINO Team and the PREPOCOL Study GroupDeterminants of Underdiagnosis of COPD in national and international surveysChest2015148497198525950276

- CastilloDBurgosFGuaytaRFARMAEPOC groupAirflow obstruction case finding in community-pharmacies: a novel strategy to reduce COPD underdiagnosisRespir Med2015109447548225754101

- ZhangJZhouJBLinXFWangQBaiCXHongQYPrevalence of undiagnosed and undertreated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in lung cancer populationRespirology201318229730223051099

- LangsetmoLPlattRErnstPBourbeauJUnderreporting exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a longitudinal cohortAm J Respir Crit Care Med200817739640118048806

- XuWColletJShapiroSNegative impacts of unreported COPD exacerbations on health-related quality of life at 1 yearEur Respir J2010351022103019897555

- MackayAJDonaldsonGCPatelARJonesPWHurstJRWedzichaJAUsefulness of the Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Assessment Test to evaluate severity of COPD exacerbationsAm J Respir Crit Care Med20121851218122422281834

- LeidyNKMurrayLTPatient-reported outcome (PRO) measures for clinical trials of COPD: the EXACT and E-RSCOPD20131039339823713600

- HuntTMadiganSWilliamsMTOldsTSUse of time in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – a systematic reviewInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis201491377138825548519

- AlmagroPLapuenteAYunSUnderdiagnosis and prognosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after percutaneous coronary intervention: a prospective studyInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2015101353136126213464

- JairamPMvan der GraafYLammersJWMaliWPde JongPAPROVIDI Study groupIncidental findings on chest CT imaging are associated with increased COPD exacerbations and mortalityThorax20157072573126024687

- IncalziRAScarlataSPennazzaGSantonicoMPedoneCChronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the elderlyEur J Intern Med201425432032824183233

- CaiSQinLTanoueLEffects of one-hour training course and spirometry on the ability of physicians to diagnose and treat chronic obstructive pulmonary diseasePLoS One2015102e011734825706774

- SchünenmannHWoodheadMAnzuetoAATS/ERS Ad Hoc Committee on Integrating and Coordinating Efforts in COPD Guideline DevelopmentA guide to guidelines for professional societies and other developers of recommendations. Introduction to integrating and coordinating efforts in COPD guideline development. An official ATS/ERS workshop reportProc Am Thorac Soc20129521521823256161

- SarcIJericTZiherlKAdherence to treatment guidelines and long-term survival in hospitalized patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ Eval Clin Pract20111743743

- WhitePThortonHPinnockHGeorgopoulouSBoothHPOver-treatment of COPD with inhaled corticosteroids – implications for safety and costs: cross-sectional observational studyPLoS One2013810e7522124194824

- LucasASmeenkFSmeeleIvan SchayckCOvertreatment with inhaled corticosteroids and diagnostic problems in primary care patients, an exploratory studyFam Pract2008252869118304973

- RocheNPribilCvan GanseEReal-life use of fluticasone propionate/salmeterol in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a French observational studyBMC Pulm Med20141415624694050

- ZbozinkovaZBarczykATkacovaRPOPE study: rationale and methodology of a study to phenotype patients with COPD in Central and Eastern EuropeInt J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis2016

- FosterJAYawnBPMaziarAJenkinsTRennardSICasebeerLEnhancing COPD management in primary care settingsMedGenMed2007932418092030

- PeabodyJLuckJDeMariaLMenonRQuality of care and health status in UkraineBMC Health Serv Res20141444625269470

- LaubeBJanssensHde JonghFEuropean Respiratory Society; International Society for Aerosols in MedicineWhat the pulmonary specialist should know about the new inhalation therapiesEur Respir J20113761308133121310878

- LeungJBhutaniMLeighRPelletierDGoodCSinDDEmpowering family physicians to impart proper inhaler teaching to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthmaCan Respir J201522526627026436910

- HaroonSJordanRTakwoingiYAdabPDiagnostic accuracy of screening tests for COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysisBMJ Open2015510e008133

- PietinalhoAKinnulaVSovijärviAChronic bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Finnish Action Programme, interim reportRespir Med200710171419142517353122

- EatonTWithySGarrettJEMercerJWhitlockRMReaHHSpirometry in primary care practice: the importance of quality assurance and the impact of spirometry workshopsChest199911641642310453871

- ZwarNAMarksGBHermizOPredictors of accuracy of diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in general practiceMed J Aust2011195416817121843115

- HillKGoldsteinRSGuyattGHPrevalence and underdiagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among patients at risk in primary careCMAJ2010182767367820371646

- RobertsCMAbediMKABarryJSPredictive value of primary care made clinical diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) with secondary care specialist diagnosis based on spirometry performed in a lung function laboratoryPrim Health Care Res Dev20091049

- BednarekMMaciejewskiJWozniakMPrevalence, severity and underdiagnosis of COPD in the primary care settingThorax200863540240718234906