Abstract

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is an inflammatory cutaneous disease with a chronic relapsing course, pruritic polymorphic lesions, and typical histopathological and immunopathological findings. According to several evidences, DH is considered the specific cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease, and the most recent guidelines of celiac disease have stated that, in celiac patients with a proven DH, a duodenal biopsy is unnecessary for the diagnosis. In this review, the most recent data about the diagnosis and the management of DH have been reported and discussed. In particular, in patients with clinical and/or histopathological findings suggestive for DH, the finding of granular IgA deposits along the dermal–epidermal junction or at the papillary tips by direct immunofluorescence (DIF) assay, together with positive results for anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody testing, allows the diagnosis. Thereafter, a gluten-free diet should be started in association with drugs, such as dapsone, that are able to control the skin manifestations during the first phases of the diet. In conclusion, although DH is a rare autoimmune disease with specific immunopathological alterations at the skin level, its importance goes beyond the skin itself and may have a big impact on the general health status and the quality of life of the patients.

Introduction

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is an inflammatory cutaneous disease with a chronic relapsing course, pruritic polymorphic lesions, and typical histopathological and immunopathological findings.

According to several evidences, DH is considered the specific cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease (CD). In fact, both diseases occur in gluten-sensitive individuals, share the same HLA haplotypes (DQ2 and DQ8), and improve following the administration of a gluten-free diet.Citation1 Moreover, patients with DH show typical CD alterations at the small bowel biopsy (ranging from villous atrophy to augmented presence of intraepithelial lymphocytes [IELs]) almost in all the cases, as well as the generation of circulating autoantibodies to tissue transglutaminase (tTG).

DH is predominately a disorder of Caucasians,Citation2 although Japanese cases are increasingly reported.Citation3 The incidence of the disease was found to be 11.5 per 100,000 in ScotlandCitation4 and ranging from 19.6 to 39.2 per 100,000 in Sweden.Citation5 In a recent study from Finland, the prevalence of DH was found to be 75.3 per 100,000 (eight times lower than the prevalence of CD in that area), while the annual incidence was found to 3.5 per 100,000 over the period 1980–2009, showing a decrease in the last years.Citation6

DH usually presents in the fourth and fifth decades, although individuals of any age can be affected. In a recent study from our group investigating 159 patients with DH, approximately 27% of the patients were below the age of 10, and 36% below the age of 20, showing that, at least in Italy, pediatric DH is more common than expected in other countries.Citation7

In 2009, the guidelines for the management of patients with DH were published by our group.Citation1 However, according to recent literature, several new findings have been reported about the clinical and immunopathological features of DH; moreover, the novel guidelines for the management of CD from the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) were developed in 2012.Citation8 Therefore, an update on the diagnosis and treatment of DH would be helpful to improve the care of the patients.

Accordingly, in the next paragraphs, the clinical and the immunopathological features that can help in the diagnosis of DH are reported. Moreover, the management of the disease, which is based both on a gluten-free diet and on medications that can help control DH in the inflammatory phases, as well as its follow-up are discussed.

Clinical features

DH usually presents with symmetrical, grouped polymorphic lesions consisting of erythema, urticarial plaques, and papules,Citation2,Citation9–Citation11 involving the extensor surfaces of the knees, elbows, shoulders, buttocks, sacral region, neck, face, and scalp. By contrast, herpetiform vesicles, which reflect the name of the disease, may occur later or are often immediately excoriated, resulting in erosions, crusted papules, or areas of postinflammatory dyschromia, and are usually not seen in the patients. Itching of variable intensity and scratching and burning sensation immediately preceding the development of lesions are common.Citation2,Citation9–Citation11

Together with these manifestations, several atypical presentations have been reported in patients with DH, including purpuric lesions resembling petechiae on hands and feet,Citation12–Citation20 leukocytoclastic vasculitis-like appearance,Citation21 palmo-plantar keratosis,Citation22 wheals of chronic urticaria,Citation23 and lesions mimicking prurigo pigmentosa.Citation24 Interestingly, in some cases patients may show erythema or severe pruritus alone, making the diagnosis challenging.Citation25 Finally, patients with DH may present the clinical manifestations associated with gastrointestinal malabsorption, although less frequently than in CD.

Clinically, the main differential diagnoses in children are atopic dermatitis, scabies, papular urticaria, and impetigo, whereas eczema, other autoimmune blistering diseases (especially IgA linear disease and bullous pemphigoid), nodular prurigo, urticaria, and polymorphic erythema should be considered in adults.Citation1

Histopathological findings

The typical histopathological findings in the lesional skin of patients with DH consist of subepidermal vesicles and blisters associated with accumulation of neutrophils at the papillary tips.Citation2,Citation10,Citation11 Sometimes, eosinophils can be found within the inflammatory infiltrate,Citation26 making difficult the differential diagnosis with bullous pemphigoid.

The histopathology of a DH skin lesion can be evocative, but it is not diagnostic, since other bullous diseases, including linear IgA dermatosis, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, and others may show similar findings.Citation1,Citation2,Citation10 Moreover, as demonstrated by Warren and Cockerell,Citation27 the histopathologic picture is unspecific in approximately 35%–40% of the cases, revealing only perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and minimal inflammation in dermal papillae. Thus, to achieve the diagnosis, histopathologic examination should be always performed in combination with DIF of perilesional skin, which represent the gold standard for the diagnosis of DH.Citation1,Citation2

Direct immunofluorescence

As just stated, DIF of uninvolved skin collected in the perilesional site is the gold standard for the diagnosis of DH.Citation1,Citation2 Two specific patterns of DIF are possible: 1) granular deposits at the dermal papillae and 2) granular deposits along the basement membrane. Sometimes, a combination of both patterns, consisting in granular IgA deposition along the basement membrane with accentuation at the papillary tips, may be present.Citation1,Citation2 Recently, a third pattern consisting of fibrillar IgA deposits mainly located at the papillary tips has been described.Citation28 Such a pattern is often seen in Japanese patients with DH, where it is described in up to 50% of the cases.Citation3

Other kinds of immune deposits that can be found by DIF are the presence of perivascular IgA deposits in the upper dermis, as well as of granular IgM or C3 deposits at the dermal–epidermal junction and/or at the dermal papillae.

DIF has a sensitivity and a specificity close to 100% for the diagnosis of DH. Moreover, according to the ESPGHAN guidelines for CD, a positive DIF in a patient with suspected DH allows for the diagnosis of CD without the need of duodenal biopsy.Citation8 DIF should be performed on uninvolved perilesional skin, since in skin lesions IgA can be removed by inflammatory cells. Moreover, patients must be on normal diet, because IgA deposits can disappear from the skin in period of times variable from weeks to months in patients on a gluten-free diet. If the patient is on a gluten-free diet, a normal gluten-containing diet should be administered and the biopsy taken after at least 1 month.

In the case of negative results for DIF in patients with a high clinical suspicion of DH, the site of the biopsy should be reconsidered and another specimen should be taken from uninvolved perilesional skin. Very rarely, cases of patients with DH showing negative DIF results are reported in the literature.Citation29–Citation31 In such cases, the combination of clinical, histopathological, and serological data, together with all the examination needed for CD, can help make the diagnosis.

Serologic analysis

Patients with DH usually show the specific antibodies that can be found in patients with CD. Among them, IgA anti-tTG antibodies are considered the most sensitive and specific ones and should be tested as the first-line serologic investigation in patients with a suspected DH. Some patients may have IgA deficiency; so the total serum IgA should be tested to exclude false-negative results from the serological investigation.

IgA anti-endomysium antibodies (EMAs), IgA and IgG anti-deamidated synthetic gliadin-derived peptides (DGP), and IgA anti-epidermal transglutaminase (eTG) antibodies are considered specific and sensitive serologic markers for DH. Finally, other kinds of antibodies are currently under investigation in both patients with DH and CD. The main features of the antibodies that can be detected in patients with DH are reported in what follows.

Anti-tTG antibodies

Anti-tTG antibodies belong to the IgA1 subclass and represent a good marker of intestinal damage and of gluten-free diet adherence in patients with the DH/CD spectrum.Citation32 The commercially available ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) kits have a sensitivity ranging from 47% to 95% and a specificity higher than 90% for the diagnosis of DH.Citation33–Citation36

Since they are detected with a validated immunoenzymatic assay that is quite cheap and easy to perform, they are currently considered the most useful serological marker in celiac patients.

EMA

Even EMA belong to the IgA1 subclass, and are directed against primate smooth muscle reticular connective tissue. The detection of EMA is based on an indirect immunofluorescence assay on monkey esophagus. EMA testing has shown a specificity close to 100% and a sensitivity ranging from 52% to 100% for the diagnosis of DH.Citation33–Citation37 As for anti-tTG, EMA are usually absent in patients on a gluten-free diet and thus represent a useful diet-compliance marker in celiac patients.Citation9–Citation11,Citation38 However, since it is more expensive, time-consuming, and operator-dependent than the anti-tTG ELISA,Citation38 EMA testing should be performed only in doubtful cases.

Anti-DGP antibodies

In patients with CD, anti-DGP antibodies show lower sensitivity and specificity than anti-tTG and EMA.Citation39,Citation40 Their role as a useful marker of CD in patients below the age of 2, in whom the other antibodies are often absent, is still under debate.Citation41–Citation43 Few reports are present in the literature about anti-DGP antibodies in patients with DH, showing results similar to those with anti-tTG ones.Citation44–Citation46 Therefore, in clinical practice, anti-DGP antibodies should be tested only in doubtful cases.

Anti-eTG antibodies

Recent evidence has demonstrated that patients with DH have antibodies directed against eTG, which is considered the specific antigen of DH.Citation47 Anti-eTG antibodies show for DH a sensitivity ranging from 52% to 100%, and a specificity higher than 90%,Citation46,Citation48–Citation50 thus giving results similar to those with anti-tTG antibodies.

Since the ELISA kit to detect anti-eTG antibodies is not widely available in all the laboratories, to date they are tested only for research purposes and not for the clinical management of the patients.

Other antibodies

Other antibodies that are currently under investigation as markers for CD and/or DH are the anti-neoepitope tTG antibodiesCitation46 and the anti-GAF3X antibodies.Citation51 Although they might be good markers for DH, further studies are required to confirm their usefulness as tools for the diagnosis of the disease.

HLA haplotypes testing

As in CD, virtually all patients with DH carry either HLA-DQ2 (DQA1*05, DQB1*02) or HLADQ8 (DQB1*0302).Citation1 Thus, the presence of these alleles provides a sensitivity of close to 100% for DE and a very high negative predictive value for the disease (ie, if individuals lack the relevant disease-associated alleles, CD can be excluded). By contrast, since 30%–40% of the general population carry such HLA alleles, the specificity of such a test is very low.Citation32

Therefore, HLA testing, if negative, may be helpful in excluding the diagnosis of DH. It can also be helpful as a screening tool for patients with high risk for CD, including first-degree relatives of patients with CD.

Small bowel biopsy

As in CD, patients with DH show intestinal involvement that can be documented by histopathology in most cases. The features include partial-to-total villous atrophy, elongated crypts, decreased villus/crypt ratio, increased mitotic index in the crypts, increased IELs density, increased IEL mitotic index, infiltration of plasma cells, lymphocytes, mast cells, and eosinophils and basophils into the lamina propria.Citation8 However, in general, the histopathological alterations found in patients with DH are milder than those found in patients with CD.

According to the Marsh classification modified by Oberhuber et al,Citation52 the intestinal damage in CD patients can be divided into different stages, ranging from the normal mucosa to villous atrophy (Marsh III).

Since DH can be considered as CD of the skin, in a patient with a proven diagnosis of DH, duodenal biopsy is no longer required to confirm the diagnosis, as stated in recent guidelines.Citation8 However, in doubtful DH cases (eg, with atypical clinical or immunopathological features), all the measures that are necessary to make a diagnosis of CD, including duodenal biopsy, should be performed. Moreover, duodenal biopsy should be performed in case of suspected gastrointestinal complications, including lymphoma.

Diagnostic algorithm

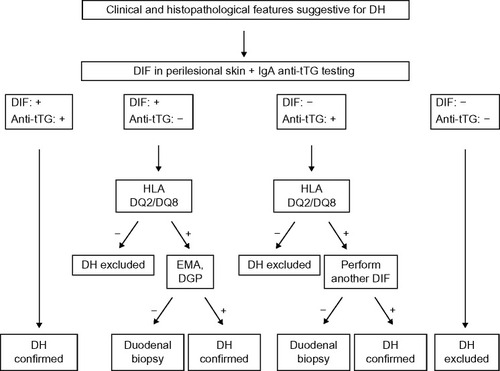

In patients with clinical and/or histopathological findings suggestive for DH, a biopsy of perilesional skin for DIF should be performed and serum samples should be collected to test anti-tTG antibodies (together with total IgA dosing). Then, basing on the evidences reported earlier, the diagnostic algorithm should be as follows ():

In case of typical findings from DIF (ie, granular IgA deposits at the dermal–epidermal junction or at the papillary tips) and of positive anti-tTG testing, the diagnosis of DH and, accordingly, of CD can be confirmed. Therefore, treatment and monitoring of DH should be managed (see text that follows).

In case of typical DIF results, but with negative anti-tTG antibodies, HLA DQ2/DQ8 testing is suggested. If negative, DH can be excluded, but if positive, patients should be further investigated. In particular, EMA and anti-DGP antibodies should be tested in order to exclude a previous false-negative result for anti-tTG antibodies. If EMA or anti-DGP antibodies are positive, DH can be confirmed. If negative, the guidelines for the diagnosis of CD should be followed,Citation8,Citation53,Citation54 including the implementation of duodenal biopsy, in order to confirm the intestinal involvement prior to starting a gluten-free diet.

In case of negative DIF and the presence of anti-tTG antibodies, HLA DQ2/DQ8 testing is suggested. If negative, DH can be excluded, but if positive, patients should be further investigated. First of all, a new skin biopsy of perilesional skin for DIF should be performed, in order to exclude false-negative results due to wrong sample collection in the previous skin biopsy. If the new DIF shows typical DH findings, the diagnosis can be confirmed. If DIF result is again negative, according to the guidelines for the diagnosis of CD, a duodenal biopsy is suggested.Citation8,Citation53,Citation54

In case of negative results both for DIF and for anti-tTG testing, DH can be excluded and the clinical and histopathological findings of the patients should be revised in order to achieve a different diagnosis.

Figure 1 Diagnostic algorithm for patients with dermatitis herpetiformis.

Treatment

As previously stated, DH is considered the specific cutaneous manifestation of CD; therefore, a lifelong gluten-free diet is the first-choice treatment of the disease. However, in the first month after the diagnosis or in the inflammatory phases of the disease, in which a gluten-free diet alone would not be enough to control the symptoms, several drugs can be used for variable periods of time, including dapsone, sulfones or steroids.

Gluten-free diet

A strict gluten-free diet is the mainstay for treatment of the spectrum DH/CD. The level of gluten allowed is <20 ppm (gluten-free); however, in some countries, products with <100 ppm (very low gluten) are allowed.

Gluten-free diet is able to resolve both the gastrointestinal and the cutaneous manifestations, as well as to prevent the development of lymphomas and other diseases associated with gluten-induced enteropathy and malabsorption.

Gluten-free diet alleviates gastrointestinal symptoms in an average of 3–6 months, which is much more rapidly than what happens with the rash; in fact, it takes an average of 1–2 years of a gluten-free diet for the complete resolution of the cutaneous lesions, which invariably recur within 12 weeks after the reintroduction of gluten. IgA antibodies may disappear from the dermal–epidermal junction after many years of a strict gluten-free diet.Citation55–Citation59

Gluten is present in cereal species of the tribe Triticeae, which includes wheat, rye, and barley.Citation56 Although in the past the basis of a gluten-free diet was the avoidance of all gluten-containing cereals, including wheat, barley, rye, and oats (mnemonic BROW), recently, some authors have demonstrated that oats belonging to the Avenae tribe can be safely consumed by celiac patients.Citation60–Citation62 However, only oats known to be pure and not contaminated in any way with wheat, barley, or rye (which is the case of the majority of commercially available oats) can be safely consumed.Citation2

As reviewed by Hischenhuber et al,Citation63 evidence-based studies show that a diet including industrially purified gluten-free wheat starch-based flours is safe for patients with DH/CD spectrum and the small-intestinal mucosa heals and stays long-term morphologically normal.Citation62

After following 133 DH patients, Garioch et alCitation57 reported several advantages of a gluten-free diet, including a reduced need for medication to treat the cutaneous manifestations, the resolution of enteropathy, a general feeling of well-being, and a protective effect against development of lymphoma. Moreover, although further evidences are required, a gluten-free diet might be helpful even in the prevention of the occurrence of DH/CD-related autoimmune disorders.

Recently, a few studies have suggested that DH can go into remission in up to 20% of the cases,Citation64,Citation65 and therefore, clinicians should continually reevaluate the need for a gluten-free diet for their patients with well-controlled DH.Citation65 However, since a gluten-free diet in patients with DH should not be considered a mere symptomatic approach to treat skin manifestation, but also the way to control and to prevent all the complications of CD, other studies are required to confirm whether the gluten-free diet can be safely discontinued.Citation66 Accordingly, lifelong commitment to a gluten-free diet is considered essential by gastroenterologists in CD and offers the patient a much better quality of life, avoidance of most complications, and an effective cure.Citation67

Even though a gluten-free diet offers many benefits in the management of DH, in practice, it is not well adopted by many DH patients. In fact, it requires scrupulous monitoring of all ingested foods, it is time-consuming, and socially restricting.Citation56 Gluten-free products are not widely available and are more expensive than their gluten-containing counterparts; moreover, contamination with small amounts of gluten is possible.Citation68 It has become evident that 20%–80% of patients with CD may continue to suffer from symptoms and still have a gluten-induced manifest mucosal lesion of Marsh II and III classes, and accordingly, some patients with DH still have skin manifestations, despite adherence to a gluten-free diet.Citation62,Citation69 Therefore, treatments alternative or integrative to the gluten-free diet in order to minimize cross-contamination accidents typically occurring outside patients’ households would represent desirable interventions to minimize the risk of complications associated with prolonged gluten exposure in subjects affected by CD and DH.Citation68

Dapsone

Although no reports from randomized controlled trials are present in the literature about its use, dapsone is considered a valid therapeutic option for patients with DH during the 6-to 24-month period until the gluten-free diet is effective.Citation70–Citation77 The starting dose should be 50 mg/d in order to minimize the potential side effects. Then the dosage can be increased up to 200 mg/d until the disease is under control; in the maintenance phase, 0.5–1 mg/kg/d generally can control itching and the development of new skin lesions.Citation71–Citation78

As just reported, several side effects are associated with dapsone use. They are usually dose-dependent and more frequent in patients with comorbidities, such as anemia, cardiopulmonary disease, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.Citation1,Citation73

They are classified into toxic, including hemolytic anemia (that usually occurs within the first 2 weeks) and methemoglobinemia, and idiosyncratic. Among the latter, dapsone hypersensitivity syndrome is considered the most severe and occurs within 2–6 weeks in approximately 5% of the patients, consisting of fever, photosensitivity, rash, malaise, lymphadenopathy, neurological effects, nephropathy, hypothyroidism, gastrointestinal symptoms and liver involvement up to hepatic failure in some cases.Citation75

Owing to these side effects, patients using dapsone should be carefully monitored. Before starting the therapy, complete blood count, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, methemoglobinemia, liver and renal functions, as well as urinalysis should be investigated. Then, patients should be reevaluated every week for the first month to monitor anemia, methemoglobinemia, and neuropathy symptoms. After the first months, complete blood count should be performed twice a month for the following 2 months and then every 3 months (together with liver and renal function testing).Citation78

Sulfasalazine, sulfapyridine, and sulfamethoxypyridazine

If dapsone fails to control the symptoms or in case of adverse effects, sulfasalazine (1–2 g/d), sulfapyridine (2–4 g/d), and sulfamethoxypyridazine (0.25–1.5 g/d) can be valid alternatives for the treatment of patients with DH.Citation2,Citation79,Citation80

All the three drugs share similar adverse effects, consisting of gastrointestinal upset (with nausea, anorexia, and vomiting), hypersensitivity drug reactions, hemolytic anemia, proteinuria, and crystalluria. Therefore, before starting the treatment, full blood count with differential and urine microscopy with urinalysis should be carried out. The same examination should be repeated monthly after the first 3 months and thereafter every 6 months.

The enteric-coated forms of the drugs, which are currently available, can prevent the symptoms associated with the gastrointestinal upset.Citation79,Citation80

Other drugs

Other drugs can be used to control the skin symptoms in patients with DH. Among them, potent (betamethasone valerate or dipropionate) or very potent (clobetasol propionate) topical steroids are helpful in cases with localized disease to reduce pruritus and the appearance of new lesions.Citation78 Accordingly, systemic steroids or antihistamines can control, at least in part, itching and burning sensation, although their effectiveness is considered quite low.Citation78

Other drugs that have been shown to be effective in some reports are topical dapsone, immunosuppressors such as cyclosporin A or azathioprine, colchicine, heparin, tetracyclines, nicotinamide, mycophenolate, and rituximab.Citation81–Citation88

Finally, several new experimental approaches for the treatment of CD are currently under investigation, including the use of engineered grains and inhibitory gliadin peptides, immunomodulatory strategies to prevent the development of an immune response against gluten, the correction of the intestinal barrier defect, and others (reviewed in Fasano et alCitation68). As happens with a gluten-free diet, such approaches might be helpful even in the control of DH skin manifestations.

Follow-up

Since DH is associated with CD, patients should be monitored following the recent guidelines for such a disease.Citation8,Citation53,Citation54 Patients with DH should be evaluated at regular intervals (6 months after diagnosis and then yearly) by a multidisciplinary team involving at least a physician and a dietitian. The purposes of these visits are to assess the compliance with the gluten-free diet and the presence of dyslipidemia, and to evaluate the possible development of intestinal malabsorption and/or celiac-related conditions, including other autoimmune diseases and complications such as refractory CD, ulcerative ileitis, celiac sprue, or lymphoma. Among the autoimmune or immune-mediated associated diseases, Hashimoto thyroiditis, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, multiple sclerosis, Sjögren syndrome, lupus erythematous, rheumatoid arthritis, vitiligo, and psoriasis are the most frequently reported, and should be investigated in patients with familiar history or evocative clinical signs.Citation87

Together with the visits, laboratory investigations, including immunological assessment, celiac-specific antibodies, and evaluation of intestinal malabsorption, should be performed. It should be remarked that there are no clear guidelines as to the optimal means to monitor adherence to a gluten-free diet. In fact, serological investigations (ie, anti-tTG or EMA) are considered to be sensitive for major, but not for minor, transient dietary indiscretions.Citation40

Conclusion

In this review, the most recent data about the diagnosis and the management of DH have been reported and discussed. Although DH is a rare autoimmune disease with specific immunopathological alterations at the skin level,Citation89 its importance goes beyond the skin itself. In fact, DH is considered a specific manifestation of gluten-sensitive enteropathy, and the National Institute of HealthCitation90 as well as the most recent ESPGHAN guidelinesCitation8 stated that a duodenal biopsy is unnecessary for the diagnosis in celiac patients with a proven DH. Therefore, not to miss a diagnosis of DH would allow the prompt introduction of a gluten-free diet, to prevent all the complications that are associated with CD and to improve the general health status as well as the quality of life of the patients.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- CaproniMAntigaEMelaniLFabbriPThe Italian Group for Cutaneous ImmunopathologyGuidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dermatitis herpetiformisJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol200923663363819470076

- FryLDermatitis herpetiformis: problems, progress and prospectsEur J Dermatol200212652353112459520

- OhataCIshiiNHamadaTDistinct characteristics in Japanese dermatitis herpetiformis: a review of all 91 Japanese patients over the last 35 yearsClin Dev Immunol2012201256216822778765

- GawkrodgerDJBlackwellJNGilmourHMDermatitis herpetiformis diagnosis diet and demographyGut19842521511576693042

- MobackenHKastrupWNilssonLAIncidence and prevalence of dermatitis herpetiformis in SwedenArch Derm Venereol1984645400404

- SalmiTTHervonenKKautiainenHCollinPReunalaTPrevalence and incidence of dermatitis herpetiformis: a 40-year prospective study from FinlandBr J Dermatol2011165235435921517799

- AntigaEVerdelliACalabròAFabbriPCaproniMClinical and immunopathological features of 159 patients with dermatitis herpetiformis: an Italian experienceG Ital Dermatol Venereol2013148216316923588141

- HusbySKoletzkoSKorponay-SzabóIREuropean Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr201254113616022197856

- YehSWAhmedBSamiNAhmedARBlistering disorders: diagnosis and treatmentDermatol Ther200316321422314510878

- NicolasMEKrausePKGibsonLEMurrayJADermatitis herpetiformisInt J Dermatol200342858860012890100

- FabbriPCaproniMDermatitis herpetiformisOrphanet Encyclopedia2200514 Available from: https://www.orpha.net/data/patho/GB/uk-DermatitisHerpetiformis.pdfAccessed December 12, 2014

- MarksRJonesEWPurpura in dermatitis herpetiformisBr J Dermatol19718443863885575205

- MoulinGBarrutDFrancMPViorneryPKnezynskiSPseudopurpuric palmar localizations of herpetiform dermatitisAnn Dermatol Venereol19831101211266881854

- KarpatiSTorokEKosnaiIDiscrete palmar and plantar symptoms in children with dermatitis herpetiformis DuhringCutis19863731841873956260

- PierceDKPurcellSMSpielvogelRLPurpuric papules and vesicles of the palms in dermatitis herpetiformisJ Am Acad Dermatol1987166127412763597876

- RuttenAGoosMPalmoplantar purpura in Duhring’s herpetiform dermatitisHautarzt198940106406432693410

- HofmannSCNashanDBruckner-TudermanLPetechiae on the fingertips as presenting symptom of dermatitis herpetiformis DuhringJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol200923673273319470074

- FlannSDegiovanniCDerrickEKMunnSETwo cases of palmar petechiae as a presentation of dermatitis herpetiformisClin Exp Dermatol201035220620820015286

- HeinlinJKnoppkeBKohlELandthalerMKarrerSDermatitis herpetiformis presenting as digital petechiaePediatr Dermatol201229220921221848992

- BoncioliniVBoncianiDVerdelliANewly described clinical and immunopathological feature of dermatitis herpetiformisClin Dev Immunol2012201296797422701503

- NaylorEAtwaterASelimMAHallRPuriPKLeukocytoclastic vasculitis as the presenting feature of dermatitis herpetiformisArch Dermatol2011147111313131622106118

- OhshimaYTamadaYMatsumotoYHashimotoTDermatitis herpetiformis Duhring with palmoplantar keratosisBr J Dermatol200314961300130214674919

- PowellGRBrucknerALWestonWLDermatitis herpetiformis presenting as chronic urticariaPediatr Dermatol200421556456715461764

- SaitoMBöerAIshikoANishikawaTAtypical dermatitis herpetiformis: a Japanese case that presented with initial lesions mimicking prurigo pigmentosaClin Exp Dermatol200631229029116487118

- Junkins-HopkinsJMDermatitis herpetiformis: pearls and pitfalls in diagnosis and managementJ Am Acad Dermatol201063352652820708475

- CaproniMFelicianiCFuligniATh2-like cytokine activity in dermatitis herpetiformisBr J Dermatol199813822422479602868

- WarrenSJCockerellCJCharacterization of a subgroup of patients with dermatitis herpetiformis with nonclassical histologic featuresAm J Dermatopathol200224430530812142608

- KoCJColegioORMossJEMcNiffJMFibrillar IgA deposition in dermatitis herpetiformis – an underreported pattern with potential clinical significanceJ Cutan Pathol201037447547719919655

- BeutnerEHBaughmanRDAustinBMPlunkettRWBinderWLA case of dermatitis herpetiformis with IgA endomysial antibodies but negative direct immunofluorescent findingsJ Am Acad Dermatol2000432 Pt 232933210901714

- SousaLBajancaRCabralJFiadeiroTDermatitis herpetiformis: should direct immunofluorescence be the only diagnostic criterion?Pediatr Dermatol200219433633912220281

- HuberCTrüebRMFrenchLEHafnerJNegative direct immunofluorescence and nonspecific histology do not exclude the diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis DuhringInt J Dermatol201352224824923347314

- RostomAMurrayJAKagnoffMFAmerican Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac diseaseGastroenterology200613161981200217087937

- PorterWMUnsworthDJLockRJHardmanCMBakerBSFryLTissue transglutaminase antibodies in dermatitis herpetiformisGastroenterology1999117374975010490368

- DieterichWLaagEBruckner-TudermanLAntibodies to tissue transglutaminase as serologic markers in patients with dermatitis herpetiformisJ Invest Dermatol1999113113313610417632

- KumarVJarzabek-ChorzelskaMSulejJRajadhyakshaMJablonskaSTissue transglutaminase and endomysial antibodies-diagnostic markers of gluten-sensitive enteropathy in dermatitis herpetiformisClin Immunol200198337838211237562

- DesaiAMKrishannRSHsuSMedical pearl: using tissue transglutaminase antibodies to diagnose dermatitis herpetiformisJ Am Acad Dermatol200553586786816243141

- Alonso-LlamazaresJGibsonLERogersRS3rdClinical, pathologic, and immunopathologic features of dermatitis herpetiformis: review of the Mayo Clinic experienceInt J Dermatol200746991091917822491

- KagnoffMFAGA Institute medical position statement on the diagnosis and treatment of celiac diseaseGastroenterology200613161977198017087935

- GiersiepenKLelgemannMStuhldreherNAccuracy of diagnostic antibody tests for coeliac disease in children: summary of an evidence reportJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr201254222924122266486

- LewisNRScottBBMeta-analysis: deamidated gliadin peptide antibody and tissue transglutaminase antibody compared as screening tests for coeliac diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther2010311738119664074

- PrauseCRitterMProbstCAntibodies against deamidated gliadin as new and accurate biomarkers of childhood coeliac diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr2009491525819465869

- AgardhDAntibodies against synthetic deamidated gliadin peptides and tissue transglutaminase for the identification of childhood celiac diseaseClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20075111276128117683995

- LiuELiMEmeryLNatural history of antibodies to deamidated gliadin peptides and transglutaminase in early childhood celiac diseaseJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200745329330017873740

- JaskowskiTDDonaldsonMRHullCMNovel screening assay performance in pediatric celiac disease and adult dermatitis herpetiformisJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr2010511192320453680

- SugaiEHwangHJVázquezHNew serology assays can detect gluten sensitivity among enteropathy patients seronegative for anti-tissue transglutaminaseClin Chem201056466166520022983

- LyttonSDAntigaEPfeifferSNeo-epitope tissue transglutaminase autoantibodies as a biomarker of the gluten sensitive skin disease–dermatitis herpetiformisClin Chim Acta201341534634923142793

- SárdyMKárpátiSMerklBPaulssonMSmythNEpidermal transglutaminase (TGase 3) is the autoantigen of dermatitis herpetiformisJ Exp Med200219574775711901200

- HullCMLiddleMHansenNElevation of IgA anti-epidermal transglutaminase antibodies in dermatitis herpetiformisBr J Dermatol2008159112012418503599

- JaskowskiTDHamblinTWilsonARIgA anti-epidermal transglutaminase antibodies in dermatitis herpetiformis and pediatric celiac diseaseJ Invest Dermatol2009129112728273019516268

- BorroniGBiagiFCioccaOIgA anti-epidermal transglutaminase autoantibodies: a sensible and sensitive marker for diagnosis of dermatitis herpetiformis in adult patientsJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol201327783684122672004

- KasperkiewiczMDähnrichCProbstCNovel assay for detecting celiac disease-associated autoantibodies in dermatitis herpetiformis using deamidated gliadin-analogous fusion peptidesJ Am Acad Dermatol201266458358821840083

- OberhuberGGranditschGVogelsangHThe histopathology of coeliac disease: time for a standardized report scheme for pathologistsEur J Gastroenterol Hepatol199911101185119410524652

- Rubio-TapiaAHillIDKellyCPCalderwoodAHMurrayJAAmerican College of GastroenterologyACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac diseaseAm J Gastroenterol2013108565667623609613

- BaiJCFriedMCorazzaGRWorld Gastroenterology Organisation global guidelines on celiac diseaseJ Clin Gastroenterol201347212112623314668

- RottmannLHDetails of the gluten-free diet for the patients with dermatitis herpetiformisClin Dermatol1992934094141806229

- TurchinIBarankinBDermatitis herpetiformis and gluten-free dietDermatol Online J2005111615748547

- GariochJJLewisHMSargentSALeonardJNFryL25′ years experience of a gluten-free diet in the treatment of dermatitis herpetiformisBr J Dermatol199413145415457947207

- LewisHMRenaulaTMGariochJJProtective effect of gluten-free diet against development of lymphoma in dermatitis herpetiformisBr J Dermatol199613533633678949426

- LembergDDayASBohaneTCoeliac disease presenting as dermatitis herpetiformis in infancyJ Pediatr Child Health2005415–6294296

- HardmanCMGariochJJLeonardJNAbsence of toxicity of oats in patients with dermatitis herpetiformisN Engl J Med199733726188418879407155

- JanatuinenBKPikkarainenSAKemppainenTAA comparison of diets with and without oats in adults with celiac diseaseN Engl J Med199533316103310377675045

- MäkiMCeliac disease treatment: gluten-free diet and beyondJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr201459Suppl 1S15S1724979194

- HischenhuberCCrevelRJarryBSafe amounts of gluten for patients with wheat allergy or coeliac diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther200623555957516480395

- BardellaMTFredellaCTrovatoCLong-term remission in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis on a normal dietBr J Dermatol2003149596897114632800

- PaekSYSteinbergSMKatzSIRemission in dermatitis herpetiformis: a cohort studyArch Dermatol2011147330130521079050

- AntigaECaproniMPieriniIBoncianiDFabbriPGluten-free diet in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis: not only a matter of skinArch Dermatol2011147898898921844467

- FricPGabrovskaDNevoralJCeliac disease, gluten-free diet, and oatsNutr Rev201169210711521294744

- FasanoANovel therapeutic/integrative approaches for celiac disease and dermatitis herpetiformisClin Dev Immunol2012201295906123093980

- TuireIMarja-LeenaLTeeaSPersistent duodenal intraepithelial lymphocytosis despite a long-term strict gluten-free diet in celiac diseaseAm J Gastroenterol2012107101563156922825364

- SenerODoganciLSafaliMBesirbelliogluBBulucuFPahsaASevere dapsone hypersensitivity sindromeJ Invest Allergol Clin Immunol2006164268270

- KosannMKDermatitis herpetiformisDermatol Online J200194814594581

- TalaricoDFMetroDGPresentation of dapsone-induced methemoglobinemia in a patient status post-bowel transplantJ Clin Anesth200517756857016297761

- LeeIBartonTDGoralSComplications related to dapsone use for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis in solid organs transplant recipientsAm J Transplant20055112791279516212642

- DamodarSViswabandyaDGeorgeBMathewsVChandyMSrivastavaADapsone for chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in children and adults – a report of 90 patientsEur J Hematol2005754328331

- Alves-RodriguesENRibeiroLCDioz SilvaMTakiuchiAFontesCJDapsone syndrome with acute renal failure during leprosy treatment: case-reportBraz J Infect Dis200591848615947852

- ChaliouliasKMayerEDarvayAAntcliffRAnterior ischaemic optic neuropathy associated with dapsoneEye200620894394516215545

- MeryLDegaHProstCDubertretLPolynévrite sensitive induite par la dapsone (Disulone®) [Dapsone-induced sensory peripheral neuropathy]Ann Dermatol Venereol20031304447449 French12843858

- BolotinDPetronic-RosicVDermatitis herpetiformis. Part II. Diagnosis, management, and prognosisJ Am Acad Dermatol20116461027103321571168

- McFaddenJPLeonardJNPowlesAVRutmanAJFryLSulphamethoxypyridazine for dermatitis herpetiformis, linear IgA disease and cicatricial pemphigoidBr J Dermatol198912167597622692691

- WillsteedELeeMWongLCCooperASulfasalazine and dermatitis herpetiformisAustralas J Dermatol200546210110315842404

- ShahSAOrmerodADDermatitis herpetiformis effectively treated with heparin, tetracycline and nicotinamideClin Exp Dermatol200025320420510844495

- AlexanderJOThe treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis with heparinBr J Dermatol19637528929314046150

- StenveldHJStarinkTMvan JoostTStoofTJEfficacy of cyclosporine in two patients with dermatitis herpetiformis resistant to conventional therapyJ Am Acad Dermatol1993286101410158496445

- JohnsonHHJrBinkleyGWNicotinic acid therapy of dermatitis herpetiformisJ Invest Dermatol195014423323815412276

- ZemtsovANeldnerKHSuccessful treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis with tetracycline and nicotinamide in a patient unable to tolerate dapsoneJ Am Acad Dermatol19932835055068445075

- SilversDNJuhlinEABerczellerPHMcSorleyJTreatment of dermatitis herpetiformis with colchicineArch Dermatol198011612137313847458365

- KotzeLMDermatitis herpetiformis, the celiac disease of the skin!Arq Gastroenterol201350323123524322197

- SchmidtETherapieoptimierung bei schweren bullösen Autoimmundermatosen [Optimizing therapy in patients with severe autoimmune blistering skin diseases]Hautarzt2009608633640 German19536513

- AntigaEQuaglinoPPieriniIRegulatory T cells as well as IL-10 are reduced in the skin of patients with dermatitis herpetiformisJ Dermatol Sci2015771546225465638

- National Institutes of Health consensus development conference statement on celiac disease, June 28–30, 2004Gastroenterology20051284 Suppl 1S1S915825115