Abstract

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSF) is a premalignant condition caused by betel chewing. It is very common in Southeast Asia but has started to spread to Europe and North America. OSF can lead to squamous cell carcinoma, a risk that is further increased by concomitant tobacco consumption. OSF is a diagnosis based on clinical symptoms and confirmation by histopathology. Hypovascularity leading to blanching of the oral mucosa, staining of teeth and gingiva, and trismus are major symptoms. Major constituents of betel quid are arecoline from betel nuts and copper, which are responsible for fibroblast dysfunction and fibrosis. A variety of extracellular and intracellular signaling pathways might be involved. Treatment of OSF is difficult, as not many large, randomized controlled trials have been conducted. The principal actions of drug therapy include antifibrotic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxygen radical mechanisms. Potential new drugs are on the horizon. Surgery may be necessary in advanced cases of trismus. Prevention is most important, as no healing can be achieved with available treatments.

Introduction

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSF) is a premalignant disorder associated with the chewing of areca nut (betel nut). The habit is prevalent in South Asian populations but has been recognized nowadays also in Europe and North America. OSF causes significant morbidity. After transformation into squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), it is also responsible for mortality. The combination of areca nut and tobacco has led to a sharp increase in the frequency of OSF.Citation1

Definition and clinical manifestations of the disease are summarized in . The initial presentation of OSF is inflammation. Inflammation is followed by hypovascularity and fibrosis visible as blanching of the oral mucosa with a marble-like appearance. Blanching may be localized, diffuse, or reticular. In some cases, small vesicles may develop that rupture and form erosions.Citation1

Table 1 Histopathological classifications of oral submucous fibrosis

In the later advanced stage of OSF, a fibrous band that restricts mouth opening (trismus) is characteristic. It causes further problems in oral hygiene, speech, mastication, and possibly swallowing. Development of fibrous bands in the lip leads to thickening and rubbery appearance. It becomes difficult to retract or evert the lips, which transform into an elliptical shape. A cross-sectional study in 325 patients in Karachi, Pakistan demonstrated a strong association among labial bands, bands in the fauces, and buccal bands. On the other hand, buccal bands had a weaker association to labial bands.Citation2

The severity of trismus can be graded by measuring the interincisor opening or mouth opening. The mouth opening is categorized into stage I (>3 cm), stage II (2–3 cm), and stage III (<2 cm).Citation3–Citation5 Fibrosis makes cheeks thick and rigid. The cheek flexibility may also be used to classify the severity of OSF. Three categories have been suggested: cheek flexibility >30 mm, 20–30 mm, and <20 mm.Citation1

Clinical features of advanced OSF include the loss of puffed-out appearance of cheeks when a patient blows a whistle. Fibrosis of tongue and mouth impairs tongue movement and leads to depapillation and blanching of mucosa.Citation1

Fibrosis may also affect the soft palate and uvula, whereas gingival involvement is relatively uncommon. Sometimes the blockage of Eustachian tubes impairs hearing, and esophageal fibrosis causes problems in swallowing.Citation1

Epidemiology

Approximately 600 million persons are betel chewing, with a hot spot throughout the Western Pacific basin and South Asia. This makes betel the fourth most-consumed drug after nicotine, ethanol, and caffeine.Citation6,Citation7

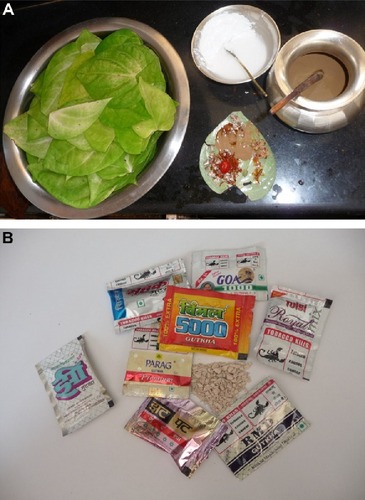

Betel is composed of the areca nut (Areca catechu), the fresh leaf of betel pepper (Piper betle), spices, and calcium hydroxide (lime) (). Pan or paan masala is a quid of piper betel leaf.Citation8 Mawa is a mixture of tobacco, lime, and areca nut. Chewing tobacco or guthka became very popular, and betel chewers often also used guthka. However, guthka has recently been officially banned from the Indian market,Citation9–Citation11 but chewing tobacco-containing betel quid has become one of the most popular habits in South Asia.Citation12 Since there is a lot in common between the various areca nut mixtures (pan, mawa) we will not differentiate between them. Betel is now widely available in the Western world as well.Citation13

Figure 1 Handmade and commercial forms of betel.

OSF subjects are younger and have shorter histories of chewing compared to chewers without OSF. OSF does not disappear after cessation of the habit but remains permanent.Citation14

A study from Gujarat has shown that the prevalence of OSF is increasing – from 0.16% (1967) to 10.9% (1998). About 85% of patients were younger than 35 years.Citation10 In 2005, the OSF prevalence among visitors at a dental school in Manipal, India was estimated as 2%, with a preference for male sex and an age range of 40–60 years.Citation15 The prevalence of OSF in an aboriginal community of southern Taiwan was 17.6%. Although the betel quid in Taiwan does not contain any tobacco, in contrast to India and Pakistan, a significant association with oral mucosal lesions was still identified.Citation16

In a study from Allahabad, India, 239 OSF patients were studied; 46% were in their 3rd decade of life. The most common affected site was buccal mucosa (20.8%), followed by palate (17.7%). Trismus was observed in 37.2% of patients, 25.9% suffered from burning sensations, 22.5% reported excessive salivation, and 14.2% suffered from recurrent oral ulcerations.Citation3

Grading OSF in relation to addiction habits demonstrated a dependence from years of addiction and frequency of chewing betel and tobacco. Most patients with stage I OSF were addicted for at least 3–5 years, whereas the majority of patients with stage III OSF had consumed betel and tobacco products for 8–10 years or more with a frequency of 6–10 times per day. Trismus was seen more often in stage II and III OSF, but a clear correlation between the severity of trismus and OSF staging was missing.Citation3

Major constituents of areca nuts

Areca nuts contain a great variety of substances. In the light of OSF, the most interesting compounds are those that are water or ethanol soluble. The alkaloid fraction contains arecoline, arecaidine, guvacine, guvacoline, arecolinidine, and others. The most predominant polyphenols are catechin, flavonoids, flavan-3:4-diols, leucocyanidins, hexahydroxyflavans, and tannin. Minor polyphenols include epicatechin, gallic acid, gallotannic acid, D-catechol, phiobatannin, and others. Furthermore, nitrosamines have been identified in areca nuts. Areca nuts also contain trace elements like copper, bromide, vanadium, manganese, chlorine, and calcium.Citation17 Betel quid chewers are exposed to increased concentrations of potentially hazardous compounds such as arsenic, cadmium, copper, and lead.Citation18

Pathogenic factors in precancerous and cancerous lesions induced by betel chewing

The relationship of OSF to chewing of areca nut/quid or pan masala has been directly related to OSF, whereas chewing or smoking tobacco did not increase the risk for OSF.Citation19 In a case–control study from Kerala, India, betel quid alone increased the odds ratio for OSF to 56.2.Citation20

Extracellular matrix and fibroblast changes

The most obvious changes occur in the extracellular matrix of the submucous tissue layer. Fibrosis is associated with quantitative and qualitative alterations of collagen deposition within the subepithelial layer of the oral mucosa. This is partly due to marked deficiencies in collagen and fibronectin phagocytosis by fibroblasts caused by betel nut alkaloids (arecoline, arecaidine).Citation21 On the other hand, tannins from areca nuts increase collagen fiber resistance to collagenase.Citation22

In vitro, areca nut extract suppresses the synthesis of [3H] proline and the growth and attachment to collagen of oral fibroblasts in a dose-dependent manner.Citation23 Pretreatment of oral mucosa fibroblasts with other areca nut compounds such as buthionine sulfoximine or diethyl maleate potentiates the cytotoxic effects.Citation24 Overexpression of stress protein colligin was found in 70% of OSF patients. It has been suggested that colligin may contribute to the increased deposition of collagen I and thereby to fibrosis development in oral submucosa.Citation25 CD34 – a marker of mucosal vascular endothelium – and basic fibroblast growth factor are both increased in OSF and demonstrate an association to the stage of fibrosis.Citation26

Arecoline – the major compound of areca nut – can induce various growth factors in OSF fibroblasts in vitro, like insulin-like growth factor-1 and keratinocyte growth factor-1, and basic protein cystatin C,Citation27–Citation29 but inhibits proinflammatory cytokines like interleukin-6.Citation30 Arecoline stimulates another key molecule in the regulation of fibrosis – the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α – in a dose-dependent manner.Citation31

Copper

Copper is implicated in the pathogenesis of fibrotic disorders because it stimulates collagen synthesis in oral fibroblasts.Citation32 Elevated serum copper levels are associated with duration of betel nut chewing and severity of OSF.Citation33

Areca nuts contain high copper concentrations compared to other nuts, and copper becomes liberated during chewing. Mass absorption spectrometry of buccal mucosa detected a mean tissue copper level of 5.5±2.9 μg/g in patients with OSF compared with 4±1.9 μg/g in controls. Copper has been detected in the epithelium and the connective tissue of the OSF specimens.Citation34 Copper levels are significantly higher in commercial areca nut products compared with raw areca nut.Citation35

Immune system

Betel quid affects the immune system. The levels of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and interferon (IFN)-γ are lower in mononuclear cells from OSF patients than from controls.Citation36,Citation37

Antioxidant status and cytokines

Glutathione S-transferases (GST) are part of the antioxidant system. GSTT1 and GSTM1 null phenotypes increase the risk of OSF.Citation38 Reduced glutathione levels in betel quid users are related to raised levels of the proinflammatory interleukin-6.Citation39 Diminished levels of superoxide dismutase but increased levels of malondialdehyde – a lipid peroxidation product – have been detected in OSF.Citation40

The role of tobacco addition

Several surveys show an increase in the incidence of OSF when areca nut and tobacco consumption are combined. A relative risk of 489 has been reported for OSF in consumers of areca nut/tobacco compared with nonusers.Citation41 The consumers of mixed products are often younger.Citation10,Citation42 OSF develops faster in these patients (after 2.7 years) than in betel quid chewers (after 8.6 years). Cancerous transformation appeared at an early age.Citation43

Both genotoxicity and carcinogenicity of areca nut and betel quid with or without tobacco admixture are well documented. Nitrosamines, reactive oxygen species, and depletion of endogenous anti-oxidant capacity are the dominant contributors.Citation38,Citation44 Esophageal subepithelial fibrosis is seen more frequently in patients who had consumed areca nut and tobacco for longer than 5 years.Citation45

Changes in gene expression and activity

More recently, the expression profiles of genes in OSF and normal oral mucosa have been studied more intensively. In one study, 14,500 genes were analyzed using gene chip arrays. The study demonstrated 716 genes were upregulated and 149 genes were downregulated in OSF. The gene expression profiles of normal controls and OSF patients were clearly distinct, in particular the genes involved in immune response, inflammatory response, and TGF-β–induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition.Citation46

In a comprehensive analysis of water-soluble and ethanol-soluble areca nut constituents, it was demonstrated that both alkaloid and polyphenol fractions induced TGF-β signaling in human keratinocytes. Involved genes included TGF-β2, SMAD-3, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)1, MMP2, and MMP9, and others. In contrast, no TGF signaling was induced in fibroblasts.Citation47

It can be assumed that direct effects on epithelial cells with TGF-β activation can suppress antifibrogenetic cytokines, including bone morphogenetic protein-7 and stimulated fibroblast activity. Both OSF and oral SCC development are quite complex and it is unlikely that a single factor is responsible.Citation48

Related conditions in oral submucous fibrosis

Betel nut chewers are also prone to benign and malignant diseases other than OSF. These diseases can occur intraorally, but also in the descending parts of the gastrointestinal tract, like esophagus or liver. Malnutrition and hepatitis virus infection are independent risk factors.Citation49

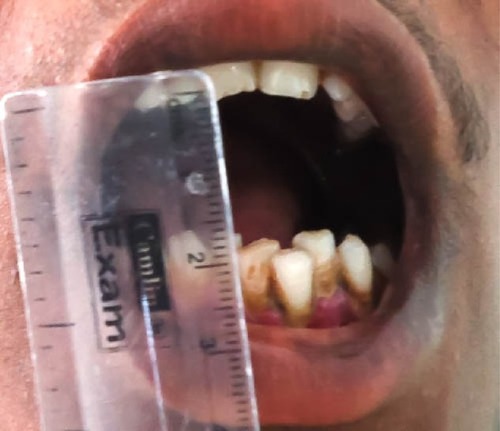

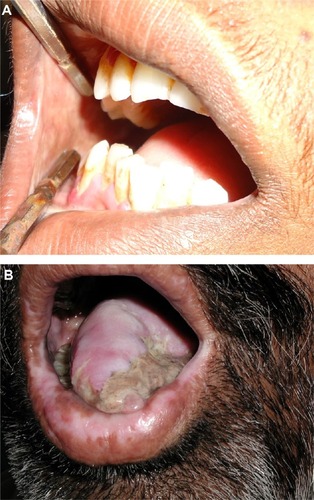

Betel chewing leads to blood-red saliva that stains teeth and gingiva. The teeth may become red-brown to nearly black ().Citation1,Citation13 Betel chewer’s mucosa (BCM) is characterized by a brownish-red discoloration and an irregular epithelial surface ( and ). The prevalence of BCM reaches up to 60% with a preference for female sex. The epithelium is often hyperplastic (). In contrast to OSF, BCM is not premalignant.Citation50–Citation52

Figure 4 Redness and irregular cobble-stone appearance in oral submucous fibrosis.

Oral leukoplakia and OSF are clinically distinct premalignant states that precede the development of oral SCC. Oral leukoplakia is an early sign of mucosal damage. It can appear as macular, plaque-like, erosive, or verrucous lesion with a homogeneous or speckled white appearance. Erythroplakia would be the reddish counterpart that poses a greater risk for malignant transformation into invasive SCC ().Citation1,Citation53

In more-advanced OSF, fibrosis is a hallmark leading to impairment in mouth opening, speaking and swallowing ( and ).Citation1,Citation2

Figure 7 Advanced-stage oral submucous fibrosis.

Oral cancer, in particular oral SCC, has been linked to areca nut chewing. The most common symptoms are related to later stages of cancer, like odynophagia, oral ulcers, or ulcer pain.Citation54 Patients with oral SCC and OSF are younger, show a higher grade of tumor differentiation, and a lower incidence of nodal and extracapsular spread ().Citation55

Oral cancer accounts for up to 40% of all malignancies in Asia.Citation56,Citation57 Tobacco smoking and chewing betel quid containing tobacco are the major risk factors for oral cancer, whereas betel quid without tobacco significantly increased oral cancer risk in only one study.Citation58 OSF makes oral cancer 19.1 times more likely.Citation8,Citation59

Attempts have been made to identify specific molecular events as prognostic markers to identify oral precancerous lesions with higher malignant potential. The expression of TGF-α and epidermal growth factor-receptor was upregulated in oral leukoplakia, OSF, and oral SCC relative to normal oral mucosa.Citation60

Arecoline is considered the most important etiological factor, but addition of peroxynitrite (a reaction product of cigarette smoking) and nicotine acted as a synergistic effect on the arecoline-induced cytotoxicity and glutathione depletion.Citation1,Citation61–Citation64 Other factors associated with malignant transformation of OSF have been identified ().Citation65–Citation77

Table 2 Factors associated with malignant transformation of oral submucous fibrosis

Esophageal involvement is the most common extraoral manifestation in betel nut chewers. Esophageal abnormalities were seen more frequently in patients who had consumed a combination of areca nut and tobacco; the esophagus may also be involved in about two-thirds of patients.Citation45 Associated visceral organ involvement has not been observed.Citation78 Cancer of the esophagus is another possible manifestation, in particular in patients who had been using fermented betel nut with any form of tobacco.Citation79

A recent meta-analysis investigated case–control studies and cohort studies from Asia. The authors found an odds ratio for esophageal SCC of 3.05 in areca nut chewers, which was further increased by additional tobacco smoking to 6.79.Citation80,Citation81 Betel quid chewing is an independent risk factor of hepatocellular carcinoma.Citation82

Recently, evidence has been gained for the association of areca nut chewing and systemic inflammation. In an observational study of 1,112 chewing individuals and 556 controls, the areca nut chewers had an odds ratio of 3.23 for C-reactive protein higher than 10 mg/dL. This might be linked to an increased risk for metabolic diseases, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.Citation83,Citation84 A possible link between betel quid chewing and cardiovascular disease could be arecoline. Arecoline is capable of blocking the high-density lipoprotein receptor with a higher affinity than cholesterol. Inhibition of cholesterol endocytosis may contribute to atherosclerosis.Citation85

A recent meta-analysis of betel quid and risk of cardiovascular disease concluded that betel quid poses a greater risk than tobacco.Citation86 Another meta-analysis concluded that betel quid is associated with two major disorders of metabolic syndrome – diabetes mellitus and central obesity.Citation87

Diagnostics

The hallmark of diagnosing OSF is clinical and histological. Clinically, one or more of the following symptoms should be present:

Blanching of oral mucosa defined as a persistent, white, marble-like appearance of the oral mucosa, which may be localized, diffuse or reticular

Tough, leathery texture of the mucosa

Palpable, whitish, fibrous bands.

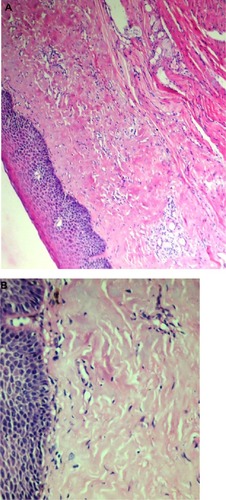

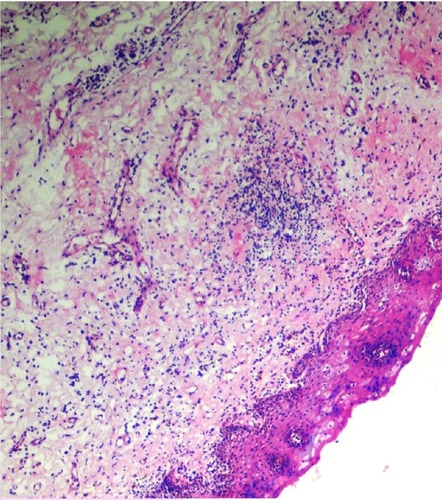

This should be accompanied by histopathological investigations. OSF is characterized by epithelial atrophy with loss of rete ridges and hyalinization of the lamina propria and the underlying muscle ().Citation1

The initial pathology of OSF is characterized by mixed inflammation and edema, and large fibroblasts (). Later, collagen bundles with early hyalinization are seen, and the inflammatory infiltrate contains lymphocytes and plasma cells, occasionally resembling lichenoid mucositis.Citation88

Figure 9 Histopathological picture showing initial stage of oral submucous fibrosis.

In more-advanced stages, OSF is characterized by formation of thick bands of collagen and hyalinization extending into the submucosal tissues and decreased vascularity (). The epithelium becomes thinner or hyperkeratotic. Inflammation and fibrosis of minor salivary glands may develop. Muscle degeneration will occur in advanced stages of OSF.Citation1,Citation82,Citation89 In vivo autofluorescence from buccal mucosa seems to be an interesting noninvasive tool to differentiate normal mucosa from OSF and early carcinoma.Citation82

Prevention and treatment

Betel nut chewing is a major risk factor for health, with the propensity for the development of malignancies of the gastrointestinal tract. The combination of risk factors like betel nut and tobacco chewing, tobacco smoking, and alcohol increases the risk of severe disease like oral SCC. Health education will probably have an influence on this habit. Lessons learned from tobacco smoking, however, argue against rapid changes due to education and information alone.

Asian immigrant communities are growing in Western countries. Some authors have suggested implementation of an oral cancer screening by health care providers. On the other hand, the concept of screening of an asymptomatic patient is not well understood by many immigrants.Citation90 Physicians and dentists in the Western world should know about OSF to make an early diagnosis that will help to reduce morbidity and mortality.Citation91,Citation92

Conventional therapies in the treatment of OSF are empirical and symptomatic in nature. The major targets of treatment can be summarized as:

anti-inflammatory

oxygen radical-scavenging

antifibrotic.Citation1

In many cases, combined drug treatment is performed, although controlled clinical trials are completely lacking. In other patients, depending on severity of disease, physical therapy and/or surgery is added to drug therapy.Citation93

Here we will focus on pharmacological therapies, although patients might benefit from physical therapy in conjunction with drug treatment. The more advanced OSF is, the more limited the efficacy of pharmacological treatment. Patients may benefit from surgery or laser surgery in such situations.Citation94–Citation96

During the early inflammatory phase of OSF, corticosteroids are of potential benefit, as suggested by in vitro studies. OSF has also been treated with hyaluronidase, chymotrypsin and collagenase, pentoxifylline, nylidrin hydrochloride, iron, and lycopene among others, but the level of evidence for any of these attempts is low.Citation94

A 6-week course of intralesional injections of 4 mg dexamethasone/mL and 1,500 U hyaluronidase twice weekly improved trismus and other clinical parameters associated with fibrosis. In addition, autofluorescence of the affected mucosa normalized for collagen and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced form) spectra.Citation96

A combination of micronutrients and minerals was evaluated in a single-arm study. Significant improvement in symptoms was observed after 1–3 years of treatment. The interincisor distance was stable in 49% of patients and improved in 41%, and leukoplakia regressed.Citation97

Oxitard is a phytopharmacological complex of antioxidant activity. In a group of 120 OSF patients, efficacy of oxitard two capsules per day was compared to topically applied 0.5% aloe vera three times daily for 3 months. Subjective symptoms like burning pain and difficulty in swallowing, and mouth opening and tongue protrusion were significantly more improved with oxitard.Citation98

Lactoferrin is a biologically active compound of bovine milk. Lactoferrin can also be produced by recombinant technology. The compound is not only immune modulating, resulting in increased antiviral and antibacterial activity of intestinal mucosa, but improves cancer surveillance and has anti-inflammatory effects.Citation99

IFN-γ that inhibits the collagen synthesis was given intralesionally in an open uncontrolled study. IFN-γ treatment showed improvement in the patient’s mouth opening with a net gain of 8±4 mm (42%) of interincisor distance 6 months later. Histochemical investigations demonstrated effects on inflammation and collagen metabolism in favor of antifibrotic activity.Citation100

Standardized treatment of OSF does not exist, but some interesting and promising drugs are available ().Citation93,Citation98,Citation101–Citation107 Controlled, prospective multicenter trials seem to be necessary. Careful monitoring of these patients is mandatory so as not to overlook early and treatable stages of oral SCC. Whenever SCCs develop, there is no special treatment but standard surgical, radiotherapeutic, and chemotherapeutic therapy like in other SCCs.

Table 3 Treatment of oral submucous fibrosis (controlled trials)

There are a number of potentially beneficial drugs that have yet not been studied systematically in OSF.

Modulating agents (antiproteinase, anti-inflammatory) seem to be of interest in gingivitis and periodontitis.Citation102

Antifibrotic compounds: synthetic drugs that show antifibrotic activities include angiotensin receptor blockers, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) inhibitors.Citation108 Protein kinase inhibitors have shown potential to decrease lung fibrosis by interaction with key enzymes, eg, focal adhesion kinase and protein kinase B.Citation109 Small interfering RNA, statins (simvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, fluvastatin, atorvastatin, cerivastatin), peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor gamma antagonists and prostaglandins are capable of blocking the profibrotic activity of connective tissue growth factor CCN2.Citation110 In patients with psoriatic arthritis, TNF-α inhibitors exert a hepatoprotective effect and prevent liver fibrosis in vivo.Citation111

There is an increasing list of herbal antifibrotic compounds, including quercetin, baicalein, baicalin, wogonin, salvianolic acid B, and emodin, that suppress collagen I expression at both the mRNA and protein levels and also decrease smooth muscle actin expression in vitro.Citation112 Some of the flavones like wogonin, baicalein, and baicalin also show anticancer activities and are oxygen radical scavengers.Citation113

N-acetyl cysteine inhibits collagen gene transcription, and production of collagen in oral mucosal cells in vitro. Furthermore, this compound has a positive impact on intracellular glutathione reserve thereby reducing redox stress to mucosal cells. The compound is not cytotoxic in vitro.Citation114

Cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors might be of some benefit during the inflammatory stage of the disease since both immunohistochemistry of OSF lesions and in vitro experiments with buccal mucosal fibroblasts exposed to arecoline demonstrated an upregulation of COX-2.Citation115

Available data are summarized in . There is a need for controlled prospective trials in OSF and for preventive programs as well.

Table 4 Potential compounds for pharmacological treatment of oral submucous fibrosis

Author contributions

Dr Verma, Dr Ali and Dr Patil have investigated the patients shown herein. All four authors fulfilled the following four conditions: 1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; 2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; 3) final approval of the version to be published; and 4) agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HaiderSMMerchantATFikreeFFRahbarMHClinical and functional staging of oral submucous fibrosisBr J Oral Maxillofac Surg2000381121510783440

- AliFMPatilAPatilKPrasantMCOral submucous fibrosis and its dermatological relationIndian Dermatol Online J20145326026525165640

- PandyaSChaudharyAKSinghMSinghMMehrotraRCorrelation of histopathological diagnosis with habits and clinical findings in oral submucous fibrosisHead Neck Oncol200911019409103

- CeenaDEBastianTSAshokLAnnigeriRGComparative study of clinicofunctional staging of oral submucous fibrosis with qualitative analysis of collagen fibers under polarizing microscopyIndian J Dent Res200920327127619884707

- PatilSMaheshwariSProposed new grading of oral submucous fibrosis based on cheek flexibilityJ Clin Exp Dent201463e255e25825136426

- NelsonBSHeischoberBBetel nut: a common drug used by naturalized citizens from India, Far East Asia, and the South Pacific IslandsAnn Emerg Med199934223824310424931

- ZainRBCultural and dietary risk factors of oral cancer and precancer –a brief overviewOral Oncol200137320521011287272

- MerchantAHusainSSHosainMPaan without tobacco: an independent risk factor for oral cancerInt J Cancer200086112813110728606

- ChaudhryKIs pan masala-containing tobacco carcinogenic?Natl Med J India1999121212710326326

- GuptaPCSinorPNBhonsleRBPawarVSMehtaHCOral submucous fibrosis in India: a new epidemic?Natl Med J India19981131131169707699

- RoyRTaxes make cigarette firms huff and puffThe Sunday Times of India, Mubai12172320021

- HeckJEMarcotteELArgosMBetel quid chewing in rural Bangladesh: prevalence, predictors and relationship to blood pressureInt J Epidemiol201241246247122253307

- NortonSABetel: consumption and consequencesJ Am Acad Dermatol199838181889448210

- VanWykCWOral submucous fibrosis. The South African experienceIndian J Dent Res19978239459495135

- MathewALPaiKMSholapurkarAAVengalMThe prevalence of oral mucosal lesions in patients visiting a dental school in Southern IndiaIndian J Dent Res20081929910318445924

- YangYHLeeHYTungSShiehTYEpidemiological survey of oral submucous fibrosis and leukoplakia in aborigines of TaiwanJ Oral Pathol Med200130421321911302240

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to HumansBetel-quid and areca-nut chewing and some areca-nut derived nitrosaminesIARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum200485133415635762

- Al-RmalliSWJenkinsROHarisPIBetel quid chewing elevated human exposure to arsenic, cadmium and leadJ Hazard Mater20111901–3697421440366

- SharmaAKGuptaRGuptaHPSinghAKHaemodynamic effects of pan masala in healthy volunteersJ Assoc Physicians India200048440040111273174

- JacobBJStraifKThomasGBetel quid without tobacco as a risk factor for oral precancersOral Oncol200440769770415172639

- ChangYCHuCCLiiCKTaiKWYangSHChouMYCytotoxicity and arecoline mechanisms in human gingival fibroblasts in vitroClin Oral Investig2001515156

- TilakaratneWMKlinikowskiMFSakuTPetersTJWarnakulasuriyaSOral submucous fibrosis: review on aetiology and pathogenesisOral Oncol200642656156816311067

- TsaiCCMaRHShiehTYDeficiency in collagen and fibronectin phagocytosis by human buccal mucosa fibroblasts in vitro as a possible mechanism for oral submucous fibrosisJ Oral Pathol Med199928259639950251

- JengJHTsaiCLHahnLJYangPJKuoYSKuoMYArecoline cytotoxicity on human oral mucosal fibroblasts related to cellular thiol and esterase activitiesFood Chem Toxicol199937775175610496377

- KaurJRaoMChakravartiNCo-expression of colligin and collagen in oral submucous fibrosis: plausible role in pathogenesisOral Oncol200137328228711287283

- PandiarDShameenaPImmunohistochemical expression of CD34 and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in oral submucous fibrosisJ Oral Maxillofac Pathol201418215516125328292

- TsaiCHYangSFChenYJChouMYChangYCThe upregulation of insulin-like growth factor-1 in oral submucous fibrosisOral Oncol200541994094616054426

- TsaiCHYangSFChenYJChouMYChangYCRaised keratinocyte growth factor-1 expression in oral submucous fibrosis in vivo and upregulated by arecoline in human buccal mucosal fibroblasts in vitroJ Oral Pathol Med200534210010515641989

- Chung-HungTShun-FaYYu-ChaoCThe upregulation of cystatin C in oral submucous fibrosisOral Oncol200743768068517070095

- UllahMCoxSKellyEMooreMAZoellnerHArecoline increases basic fibroblast growth factor but reduces expression of IL-1, IL-6, G-CSF and GM-CSF in human umbilical vein endotheliumJ Oral Pathol Med Epub12192014

- TsaiCHLeeSSChangYCHypoxic regulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression in human buccal mucosa fibroblasts stimulated with arecolineJ Oral Pathol Med Epub1142014

- TrivedyCMeghjiSWarnakulasuriyaKAJohnsonNWHarrisMCopper stimulates human oral fibroblasts in vitro: a role in the pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosisJ Oral Pathol Med200130846547011545237

- HosthorSSMaheshPPriyaSASharadaPJyotsnaMChitraSQuantitative analysis of serum levels of trace elements in patients with oral submucous fibrosis and oral squamous cell carcinoma: A randomized cross-sectional studyJ Oral Maxillofac Pathol2014181465124959037

- TrivedyCRWarnakulasuriyaKAPetersTJSenkusRHazareyVKJohnsonNWRaised tissue copper levels in oral submucous fibrosisJ Oral Pathol Med200029624124810890553

- MathewPAustinRDVargheseSSManojkumarEstimation and comparison of copper content in raw areca nuts and commercial areca nut products: implications in increasing prevalence of oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF)J Clin Diagn Res20148124724924596787

- HsuHJChangKLYangYHShiehTYThe effects of arecoline on the release of cytokines using cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with oral mucous diseasesKaohsiung J Med Sci200117417518211482128

- HaqueMFMeghjiSKhitabUHarrisMOral submucous fibrosis patients have altered levels of cytokine productionJ Oral Pathol Med200029312312810738939

- BathiRJRaoRMutalikSGST null genotype and antioxidants: risk indicators for oral pre-cancer and cancerIndian J Dent Res200920329830319884712

- TsaiCHYangSFChenYJChuSCHsiehYSChangYCRegulation of interleukin-6 expression by arecoline in human buccal mucosal fibroblasts is related to intracellular glutathione levelsOral Dis200410636036415533212

- Avinash TejasviMLBangiBBGeethaPEstimation of serum superoxide dismutase and serum malondialdehyde in oral submucous fibrosis: a clinical and biochemical studyJ Cancer Res Ther201410372272525313767

- HazareVKGoelRRGuptaPCOral submucous fibrosis, areca nut and pan masala use: a case-control studyNatl Med J India199811629910083804

- ShahNSharmaPPRole of chewing and smoking habits in the etiology of oral submucous fibrosis (OSF): a case-control studyJ Oral Pathol Med199827104754799831959

- BabuSBhatRVKumarPUA comparative clinico-pathological study of oral submucous fibrosis in habitual chewers of pan masala and betelquidJ Toxicol Clin Toxicol19963433173228667470

- NairUBartschHNairJAlert for an epidemic of oral cancer due to use of the betel quid substitutes gutkha and pan masala: a review of agents and causative mechanismsMutagenesis200419425126215215323

- MisraSPMisraVDwivediMGuptaSCOesophageal subepithelial fibrosis: an extension of oral submucosal fibrosisPostgrad Med J19987487873373610320888

- HuYJianXPengJJiangXLiNZhouSGene expression profiling of oral submucous fibrosis using oligonucleotide microarrayOncol Rep200820228729418636188

- KhanIKumarNPantINarraSKondaiahPActivation of TGF-β pathway by areca nut constituents: a possible cause of oral submucous fibrosisPLoS One2012712e5180623284772

- WollinaUVermaSParikhDParikhAOral and extraoral disease due to betel nut chewingHautarzt20025312795797 German12444519

- ReichartPANguyenXHBetel quid chewing, oral cancer and other oral mucosal diseases in Vietnam: a reviewJ Oral Pathol Med200837951151418624933

- JengJHHahnLJLinBRHsiehCCChanCPChangMCEffects of areca nut, inflorescence piper betle extracts and arecoline on cytotoxicity, total and unscheduled DNA synthesis in cultured gingival keratinocytesJ Oral Pathol Med199928264719950252

- RamaeshTMendisBRRatnatungaNThattilROThe effect of tobacco smoking and of betel chewing with tobacco on the buccal mucosa: a cytomorphometric analysisJ Oral Pathol Med199928938538810535360

- SharanRNMehrotraRChoudhuryYAsotraKAssociation of betel nut with carcinogenesis: revisit with a clinical perspectivePLoS One201278e4275922912735

- MuttagiSSChaturvediPGaikwadRSinghBPawarPHead and neck squamous cell carcinoma in chronic areca nut chewing Indian women: Case series and review of literatureIndian J Med Paediatr Oncol2012331323522754206

- ChaturvediPVaishampayanSSNairSOral squamous cell carcinoma arising in background of oral submucous fibrosis: a clinicopathologically distinct diseaseHead Neck201335101404140922972608

- ChandraSIncidence of oral leukoplakia and “Pan” chewing in Varanasi (India) dental outdoor patientsJ Indian Dent Assoc19663892612635225997

- PindborgJJKiaerJGuptaPCChawlaTNStudies in oral leukoplakias. Prevalence of leukoplakia among 10,000 persons in Lucknow, India, with special reference to use of tobacco and betel nutBull World Health Organ19673711091165300044

- ThomasSWilsonAA quantitative evaluation of the aetiological role of betel quid in oral carcinogenesisEur J Cancer B Oral Oncol199329B426527111706419

- CoxSOral cancer in Australia – risk factors and distributionAnn R Australas Coll Dent Surg20001526126311709951

- SrinivasanMJewellSDEvaluation of TGF-alpha and EGFR expression in oral leukoplakia and oral submucous fibrosis by quantitative immunohistochemistryOncology200161428429211721175

- ChangMCLinLDWuHLAreca nut-induced buccal mucosa fibroblast contraction and its signaling: a potential role in oral submucous fibrosis – a precancer conditionCarcinogenesis20133451096110423349021

- ChangYCTaiKWChouMYTsengTHSynergistic effects of peroxynitrite on arecoline-induced cytotoxicity in human buccal mucosal fibroblastsToxicol Lett20001181–2616811137310

- ChangYCHuCCLiiCKTaiKWYangSHChouMYCytotoxicity and arecoline mechanisms in human gingival fibroblasts in vitroClin Oral Investig2001515156

- ChangMCHoYSLeePHAreca nut extract and arecoline induced the cell cycle arrest but not apoptosis of cultured oral KB epithelial cells: association of glutathione, reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial membrane potentialCarcinogenesis20012291527153511532876

- LeeSSTsaiCHYuCCHoYCHsuHIChangYCThe expression of O(6)-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase in human oral keratinocytes stimulated with arecolineJ Oral Pathol Med201342860060523278137

- ChangYCHuCCTsengTHTaiKWLiiCKChouMYSynergistic effects of nicotine on arecoline-induced cytotoxicity in human buccal mucosal fibroblastsJ Oral Pathol Med200130845846411545236

- BaralRPatnaikSDasBRCo-overexpression of p53 and c-myc proteins linked with advanced stages of betel- and tobacco-related oral squamous cell carcinomas from eastern IndiaEur J Oral Sci199810659079139786319

- KannanKMunirajanAKKrishnamurthyJLow incidence of p53 mutations in betel quid and tobacco chewing-associated oral squamous carcinoma from IndiaInt J Oncol19991561133113610568819

- HsiehLLWangPFChenIHCharacteristics of mutations in the p53 gene in oral squamous cell carcinoma associated with betel quid chewing and cigarette smoking in TaiwaneseCarcinogenesis20012291497150311532872

- AgarwalSMathurMShuklaNKRalhanRExpression of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p21waf1/cip1 in premalignant and malignant oral lesions: relationship with p53 statusOral Oncol19983453533609861340

- RalhanRSandhyaAMeeraMBohdanWNootanSKInduction of MDM2-P2 transcripts correlates with stabilized wild-type p53 in betel- and tobacco-related human oral cancerAm J Pathol2000157258759610934161

- HoTJChiangCPHongCYKokSHKuoYSYen-Ping KuoMInduction of the c-jun protooncogene expression by areca nut extract and arecoline on oral mucosal fibroblastsOral Oncol200036543243610964049

- LeeHCYinPHYuTNAccumulation of mitochondrial DNA deletions in human oral tissues – effects of betel quid chewing and oral cancerMutat Res20014931–2677411516716

- KaurJSrivastavaARalhanRExpression of 70-kDa heat shock protein in oral lesions: marker of biological stress or pathogenicityOral Oncol19983464965019930361

- RajendraRGeorgeBSivakaranSNarendranathanNVisceral organ involvement is infrequent in oral submucous fibrosis (OSF)Indian J Dent Res200112172011441804

- LeeSSTsaiCHHoYCYuCCChangYCHeat shock protein 27 expression in areca quid chewing-associated oral squamous cell carcinomasOral Dis201218771371922490108

- TungCLLinSTChouHCProteomics-based identification of plasma biomarkers in oral squamous cell carcinomaJ Pharm Biomed Anal20137571723312379

- PhukanRKAliMSChetiaCKMahantaJBetel nut and tobacco chewing; potential risk factors of cancer of oesophagus in Assam, IndiaBr J Cancer200185566166711531248

- TsaiJFChuangLYJengJEBetel quid chewing as a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control studyBr J Cancer200184570971311237396

- AkhtarSAreca nut chewing and esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma risk in Asians: A meta-analysis of case-control studiesCancer Causes Control201324225726523224324

- ChenPTKuanFCHuangCEIncidence and patterns of second primary malignancies following oral cavity cancers in a prevalent area of betel-nut chewing: a population-based cohort of 26,166 patients in TaiwanJpn J Clin Oncol201141121336134322025556

- HarisPSBalanAJayasreeRSGuptaAKAutofluorescence spectroscopy for the in vivo evaluation of oral submucous fibrosisPhotomed Laser Surg200927575776119712020

- ShafiqueKMirzaSSVartPAreca nut chewing and systemic inflammation: evidence of a common pathway for systemic diseasesJ Inflamm (Lond)2012912222676449

- TsaiWCWuMTWangGJChewing areca nut increases the risk of coronary artery disease in Taiwanese men: a case-control studyBMC Public Health20121216222397501

- ChoudhuryMDChetiaPChoudhuryKDTalukdarADDatta-ChoudhariMAtherogenic effect of Arecoline: A computational studyBioinformation20128522923222493525

- ZhangLNYangYMXuZRGuiQFHuQQChewing substances with or without tobacco and risk of cardiovascular disease in Asia: a meta-analysisJ Zhejiang Univ Sci B201011968168920803772

- JavedFAl-HezaimiKWarnakulasuriyaSAreca-nut chewing habit is a significant risk factor for metabolic syndrome: a systematic reviewJ Nutr Health Aging201216544544822555788

- ReichartPAWarnakulasuriyaSOral lichenoid contact lesions induced by areca nut and betel quid chewing: a mini reviewJ Investig Clin Dent201233163166

- LeeCKTsaiMTLeeHCDiagnosis of oral submucous fibrosis with optical coherence tomographyJ Biomed Opt200914505400819895110

- AuluckAHislopGPohCZhangLRosinMPAreca nut and betel quid chewing among South Asian immigrants to Western countries and its implications for oral cancer screeningRural Remote Health200992111819445556

- SukumarSColemanHGCoxSCAreca nut chewing in an expatriate population in Sydney: report of two casesAust Dent J201257337337822924364

- AuluckARosinMPZhangLSumanthKNOral submucous fibrosis, a clinically benign but potentially malignant disease: report of 3 cases and review of the literatureJ Can Dent Assoc200874873574018845065

- SharmaJKGuptaAKMukhijaRDNigamPClinical experience with the use of peripheral vasodilator in oral disordersInt J Oral Maxillofac Surg19871666956993125268

- MehrotraRSinghHPGuptaSCSinghMJainSPentoxifylline therapy in the management of oral submucous fibrosisAsian Pac J Cancer Prev201112497197421790236

- CholeRHGondivkarSMGadbailARReview of drug treatment of oral submucous fibrosisOral Oncol201248539339822206808

- AzizSRLack of reliable evidence for oral submucous fibrosis treatmentsEvid Based Dent20091018919322218

- GuptaDSharmaSCOral submucous fibrosis – a new treatment regimenJ Oral Maxillofac Surg198846108308333171741

- VedeswariCPJayachandranSGanesanSIn vivo autofluorescence characteristics of pre- and post-treated oral submucous fibrosis: a pilot studyIndian J Dent Res200920326126719884705

- PatilSHalgattiVMaheshwariSSantoshBSComparative study of the efficacy of herbal antioxdants oxitard and aloe vera in the treatment of oral submucous fibrosisJ Clin Exp Dent201463wwe265e270

- LönnerdalBNutritional roles of lactoferrinCurr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care200912329329719318940

- HaqueMFMeghjiSNazirRHarrisMInterferon gamma (IFN-gamma) may reverse oral submucous fibrosisJ Oral Pathol Med2001301122111140895

- AlamSAliIGiriKYEfficacy of aloe vera gel as an adjuvant treatment of oral submucous fibrosisOral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol2013116671772424237724

- JiangXWZhangYYangSKZhangHLuKSunGLEfficacy of salvianolic acid B combined with triamcinolone acetonide in the treatment of oral submucous fibrosisOral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol2013115333934423260769

- BhadageCJUmarjiHRShahKVälimaaHVasodilator isoxsuprine alleviates symptoms of oral submucous fibrosisClin Oral Investig201317513751382

- SinghMNiranjanHSMehrotraRSharmaDGuptaSCEfficacy of hydrocortisone acetate/hyaluronidase vs triamcinolone acetonide/hyaluronidase in the treatment of oral submucous fibrosisIndian J Med Res201013166566920516538

- CoxSZoellnerHPhysiotherapeutic treatment improves oral opening in oral submucous fibrosisJ Oral Pathol Med200938222022618673417

- KumarABagewadiAKeluskarVSinghMEfficacy of lycopene in the management of oral submucous fibrosisOral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod2007103220721317234537

- TaiYSLiuBYWangJTSunAKwanHWChiangCPOral administration of milk from cows immunized with human intestinal bacteria leads to significant improvements of symptoms and signs in patients with oral submucous fibrosisJ Oral Pathol Med2001301061862511722712

- ReddyMSGeursNCGunsolleyJCPeriodontal host modulation with antiproteinase, anti-inflammatory, and bone-sparing agents. A systematic reviewAnn Periodontol200381123714971246

- SzabòHFiorinoGSpinelliAReview article: anti-fibrotic agents for the treatment of Crohn’s disease – lessons learnt from other diseasesAliment Pharmacol Ther201031218920119832726

- Garneau-TsodikovaSThannickalVJProtein kinase inhibitors in the treatment of pulmonary fibrosisCurr Med Chem200815252632264018855683

- BrigstockDRStrategies for blocking the fibrogenic actions of connective tissue growth factors (CCN2): From pharmacological inhibition in vitro to targeted siRNA therapy in vivoJ Cell Commun Signal20093151819294531

- SeitzMReichenbachSMöllerBZwahlenMVilligerPMDufourJFHepatoprotective effect of tumour necrosis factor alpha blockade in psoriatic arthritis: a cross-sectional studyAnn Rheum Dis20106961148115019854710

- HuQNoorMWongYFIn vitro anti-fibrotic activities of herbal compounds and herbsNephrol Dial Transplant200924103033304119474275

- Li-WeberMNew therapeutic aspects of flavones: the anticancer properties of Scutellaria and its main active constituents Wogonin, Baicalein and BaicalinCancer Treat Rev2009351576819004559

- SatoNUenoTKuboKN-Acetyl cysteine (NAC) inhibits proliferation, collagen gene transcription, and redox stress in rat palatal mucosal cellsDent Mater200925121532154019679343