Abstract

Background and aims:

The study’s aim was to evaluate the efficacy of endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) compared with endoscopic band ligation (EBL) in treating rectal varices.

Methods:

Data from 34 consecutive patients who underwent endoscopic treatments for rectal varices were analyzed. The clinical outcomes, including complications, related to EIS or EBL retrospectively.

Results:

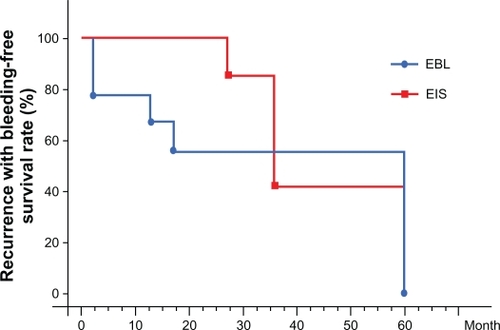

In 25 of the 34 patients, EIS was performed weekly 2–5 times (mean, 2.7), and the total amount of sclerosant ranged from 3.2 to 12.0 mL (mean, 5.2 mL). After EIS, colonoscopy revealed shrinkage of the rectal varices in all 25 patients, with no complications reported. In 9 of the 34 patients, EBL was performed weekly 1–3 times (mean, 2.2), and bands were placed on the varices at 2–12 sites (mean, 8.0). After EBL, colonoscopy revealed ulcers and shrinkage of the rectal varices in all nine patients, eight of whom experienced no operative complications. The overall recurrence rate for rectal varices was 10 of 24 (41.7%), including 5 of 9 (55.6%) receiving EBL and 5 of 15 (33.3%) receiving EIS, over a 1-year follow-up period (n = 24). All four patients with recurrence of bleeding were EBL cases, versus no EIS cases (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

EIS appears superior to EBL with regard to effectiveness and complications after endoscopic treatment of rectal varices.

Introduction

Rectal varices have been reported to occur with high frequency in patients with hepatic abnormalities.Citation1–Citation3 Hosking et al reported that 44 of 100 consecutive cirrhotic patients had anorectal varices.Citation1 Other studies found that the prevalence of anorectal varices was 78% in 72 portal hypertensive patientsCitation2 and 43% in 103 cirrhotic patients.Citation3 Massive bleeding from rectal varices occurs rarely, at a frequency ranging from 0.5% to 3.6%.Citation4–Citation6 Rectal varices are an infrequent but potentially serious cause of hematochezia. Although endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) and endoscopic band ligation (EBL) for esophageal varices are well-established therapies, there is no standard treatment for rectal varices. In this study, we retrospectively evaluated the therapeutic effects and complications of EIS versus EBL on rectal varices in patients with portal hypertension.

Patients and methods

Patients

This study retrospectively evaluated 34 consecutive patients with portal hypertension who had undergone EIS or EBL for rectal varices in the Department of Gastroenterology, Sapporo Kosei Hospital from April 1996 to December 2009. There were 15 males and 19 females, ranging in age from 38 to 84 years (mean, 67.0 years). Twenty of the 34 patients had histories of rectal bleeding, and colonoscopy revealed the high-risk sign (red color [RC]-positivity) of variceal ruptureCitation7 in the other 14 patients. EBL was performed for the first nine rectal variceal patients, and EIS was done for the next 25 patients because of establishment of EIS method for rectal varices. The underlying pathologies causing portal hypertension included liver cirrhosis (LC) in 18 patients, cirrhosis associated with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in seven patients, idiopathic portal hypertension (IPH) in four patients, primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) in three patients, and extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHO) in two patients (). In terms of the clinical staging of cirrhosis, 16 patients were graded Child-Pugh class A, 16 class B, and 2 class C. The etiologies of LC were: hepatitis B surface antigen (HBs Ag)-positivity in four patients, antibody to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV)-positivity in 11 patients, alcoholic liver disease in seven patients, sarcoidosis in one patient, and unknown in two patients.

Table 1 Clinicopathological features of patients with rectal varices

All 34 patients with portal hypertension had previously received emergency or prophylactic EIS for esophageal varices. Seven patients had a history of esophageal variceal bleeding, and emergency EIS had been performed in these cases. Prophylactic EIS had been performed on 27 patients with esophageal varices because of a high risk of bleeding. Recent endoscopic findings related to esophageal varices were as follows: six cases with small, straight, RC-positive varices, and 28 with no varices.

Endoscopic findings for rectal varices

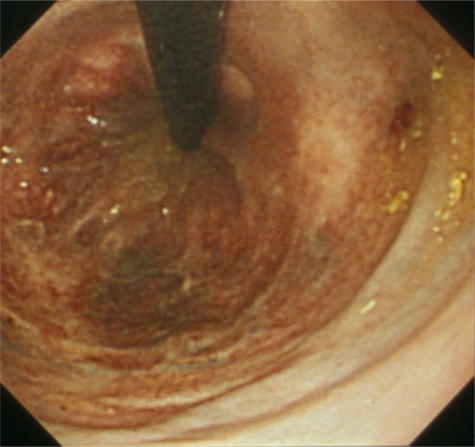

The endoscopic findings for rectal varices were evaluated according to the grading system outlined in ‘The General Rules for Recording Endoscopic Findings of Esophagogastric Varices’ prepared by the Japanese Research Committee on Portal Hypertension.Citation8 The form (F) of the varices was classified as small and straight (F1), enlarged and tortuous (F2), large and coil-shaped (F3), or no varices after treatment (F0). The fundamental color of the varices was classified as either white (Cw) or blue (Cb). The RC sign referred to dilated, small vessels or telangiectasia on the variceal surface. Rectal varices with grades of Cb, F2, and RC-positive were observed in 31 of the 34 patients, and grades of Cb, F3, and RC-positive in the other three patients ().

The study was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to the procedure. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Sapporo Kosei Hospital (Sapporo, Japan).

Methods

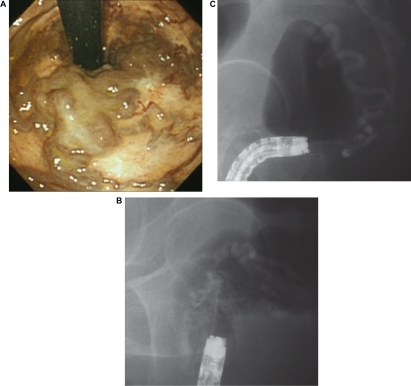

EIS was performed in 25 patients (14 of whom had a history of rectal bleeding, and the remaining 11 patients were determined to have a high risk of variceal bleeding based on endoscopic findings.Citation7 In these EIS-treated patients, the underlying pathologies causing portal hypertension included LC in 13 patients, cirrhosis associated with HCC in six patients, IPH in three patients, PBC in two patients, and EHO in one patient. Cirrhosis was graded in 11 patients as Child–Pugh class A, in 13 patients as class B, and in one patient as class C (). EIS was performed weekly using 5% ethanolamine oleate with iopamidol (EOI), which was injected to rectal varices intermittently under fluoroscopy. shows Cb, F2, RC-positive rectal varices, and EIS was performed under fluoroscopy. The fluoroscopic observation with infusion of 5% EOI was performed to determine the extent of the varices ( and ).

Figure 1 A) Cb, F2, RC-positive rectal varices. B) Fluoroscopic observation with infusion of 5% EOI was performed to determine the extent of the varices. C) One week after, fluoroscopic observation with infusion of 5% EOI.

EBL was performed in nine patients (six of whom had a history of rectal bleeding, and the remaining three patients had a high risk of variceal bleeding based on endoscopic findings). In these EBL-treated patients, the underlying pathologies causing portal hypertension included LC in five patients, cirrhosis associated with HCC in one patient, IPH in one patient, PBC in one patient, and EHO in one patient. Cirrhosis was graded in five patients as Child–Pugh class A, in three patients as class B, and in one patient as class C (). In these nine patients, EBL was performed weekly using a pneumo-activated device (Sumitomo Bakelite, Tokyo, Japan), and bands were placed on the varices. An overtube was not used during EBL.

EIS and EBL were performed until the rectal varices were completely eradicated. We defined variceal recurrence as bleeding from rectal varices or possible RC sign. We evaluated the therapeutic effects, complications, and recurrence rates after EIS or EBL. We did not use beta blockers in each of the EIS and EBL groups.

Statistical analysis

Recurrence rates were calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method using StatView® software (SAS® Institute Inc., Cary, NC), and data were analyzed using the Breslow–Gehan–Wilcoxon test for between-group comparisons. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

In 25 of the 34 patients, EIS was performed weekly from 2 to 5 times (mean, 2.7), and the total amount of sclerosant injected ranged from 3.2 to 12.0 mL (mean, 5.2 mL). After EIS, colonoscopy revealed shrinkage of the rectal varices () in all 25 patients, with no complications reported.

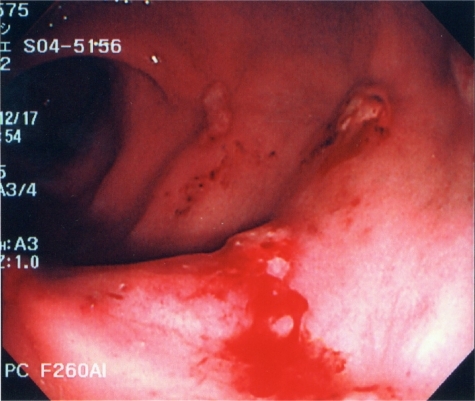

In 9 of the 34 patients, EBL was performed weekly from 1 to 3 times (mean, 2.2), and bands were placed on the varices at 2–12 sites (mean, 8.0). After EBL, colonoscopy revealed ulcers and improvement of the varices in the rectum of all nine patients. Eight of the nine patients experienced no operative complications, but colonoscopy revealed bleeding from ulcers after EBL in one case (). Endoscopic clipping was performed on the oozing ulcers in this case.

The overall rate of recurrence of rectal varices over the 1-year follow-up period (n = 24) after treatments was 10 of 24 patients (41.7%), including 5 of 9 patients (55.6%) receiving EBL and 5 of 15 patients (33.3%) receiving EIS. The recurrence rate showed no statistically significant difference between the EIS group and the EBL group. The recurrence rate with bleeding was 4 of 10 patients with recurrent rectal varices (40.0%), including 4 of the 5 patients (80.0%) receiving EBL but none of the 5 patients (0%) receiving EIS. The recurrence rate with bleeding in the EBL group was significantly higher than that in the EIS group (P < 0.05) (). After the treatments for rectal varices, there was no episode of esophagogastric variceal bleeding in all these cases.

Discussion

Esophagogastric varices are considered to be the most common complication in patients with portal hypertension, while ectopic varices (ie, those outside the esophagogastric region) are less common. Rectal varices represent portal systemic collaterals that are manifested as discrete dilated submucosal veins and constitute a pathway for portal venous flow between the superior rectal veins of the inferior mesenteric system and the middle inferior rectal veins of the iliac system. Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has become a useful modality for hemodynamic diagnosis of esophagogastric varices.Citation9,Citation10 The usefulness of EUSCitation11–Citation13 in the hemodynamic diagnosis of rectal varices has been described, and Dhiman et al found rectal varices via endoscopy in 43% of patients and via EUS in 75% of patients with portal hypertension.Citation13

Endoscopic color Doppler ultrasonography (ECDUS) is better equipped than conventional EUS to visualize in detail the hemodynamics of esophagogastric varices.Citation14,Citation15 ECDUS is useful for detecting rectal varices through color flow images, and it optimizes the effectiveness and safety of EIS by measuring the velocity of blood flow in rectal varices.Citation16

Recently, color Doppler ultrasonography has become widely accepted for the assessment of the hemodynamics of abdominal vascular systems, but few color Doppler findings related to gastrointestinal varices have been reported. Komatsuda et al reported the usefulness of color Doppler ultrasonography for the diagnosis of gastric and duodenal varices,Citation17 and Sato et al concluded that this technology was useful for evaluating the hemodynamics of rectal varices.Citation18

Various medical treatments have been used to control bleeding from rectal varices, but none of these is currently considered to be a standard method. Surgical approaches include portosystemic shunting, ligation, and under-running suturing.Citation1 Some investigators have reported that interventional radiologic techniques such as transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts were successfully employed for rectal variceal bleeding.Citation19–Citation21 We have used EIS or EBL to treat rectal varices. In this study, we retrospectively evaluated the therapeutic effects and rates of recurrence of rectal varices after EIS or EBL. Wang et al first reported the usefulness of EIS in treating rectal varices and found it to be effective for controlling bleeding.Citation22 In our study, we performed EIS in 25 of the 34 patients, which were successfully treated without complications. It is necessary to evaluate the hemodynamics of the rectal varices before EIS to avoid severe complications such as pulmonary embolism, and the sclerosant should be slowly injected under fluoroscopy, taking care to ensure that the agent does not flow into the systemic circulation.

EBL was introduced as a new method for treating esophageal varices, and it is reportedly both easier to perform and safer than EIS. Several cases of successful treatment of rectal varices using EBL have been reported.Citation23–Citation25 Levine et al treated rectal varices initially with EIS, and 1 week later, EBL was performed on the remaining rectal varices. These investigators described EBL as a safe and effective therapy for rectal varices.Citation23

The overall recurrence rate for rectal varices over the 1-year follow-up period after treatments was 10 of 24 (41.7%). We suspected that the high recurrence rate after endoscopic therapies was caused by not using the mucosal–fibrosis methodCitation26 on the rectum. The patients with recurrence included 5 of the 15 patients (33.3%) receiving EIS and 5 of the 9 (55.6%) who received EBL. The recurrence rate was not significantly different between the EIS group and EBL groups, although recurrence tended to be more frequent with EBL. Therefore, EBL may be suitable as an initial treatment for rectal varices, but it appears that the varices can easily recur after EBL.Citation27,Citation28 Shudo et al reported a case report of rectal varices that was treated with concurrent EBL and EIS treatment.Citation29 Furthermore, after EBL, bleeding from ulcers in need of endoscopic clipping occurred in one of our cases. The recurrence rate for bleeding in the EBL group was significantly higher than in the EIS group. All four patients with recurrence of bleeding had been treated using EBL. The literature does not include reports of long-term comparative follow-up of large numbers of patients with rectal varices treated using EIS in comparison with EBL. Our report is the first of its kind including the results of long-term follow-up of relatively large numbers of portal hypertensive patients with rectal varices treated using endoscopic methods. In general, beta blockers are used effectively for prophylaxis of esophageal varices in Europe and North America. However, there is no report on the role of beta blocker use for rectal varices.

In conclusion, EIS appears to be superior to EBL with regard to long-term effectiveness and complications following endoscopic treatment of rectal varices in patients with portal hypertension. More investigations are necessary in larger numbers of patients before evidence-based treatment recommendations can be made.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest in relation to this work.

References

- HoskingSWSmartHLJohnsonAGTrigerDRAnorectal varices, hemorrhoids, and portal hypertensionLancet1989183493522563507

- WangTFLeeFYTsaiYTRelationship of portal pressure, anorectal varices and hemorrhoids in cirrhotic patientsJ Hepatol1992151701731506636

- ChawlaYKDilawariJBAnorectal varices – their frequency in cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic portal hypertensionGut1991323093112013427

- McCormackTTBaileyHRSimmsJMJohnsonAGRectal varices are not pilesBr J Surg1984711636692118

- JohansenKBardinJOrloffMJMassive bleeding from hemorrhoidal varices in portal hypertensionJAMA1980224208420856968834

- WilsonSEStoneRTChristieJPPassaroEMassive lower gastrointestinal bleeding from intestinal varicesArch Surg197911411581161314792

- BeppuKInokuchiKKoyanagiNPrediction of variceal hemorrhage by esophageal endoscopyGastrointest Endosc1981272132186975734

- IdezukiYGeneral rules for recording endoscopic findings of esophagogastric varicesWorld J Surg1995194204237638999

- CalettiGCBolondiLZaniEDetection of portal hypertension and esophageal varices by means of endoscopic ultrasonographyScand J Gastroenterol19861237477

- CalettiGCBrocchiEFerrariAFiorinoSBarbaraLValue of endoscopic ultrasonography in the management of portal hypertensionEndoscopy1992243423461633778

- DhimanRKChoudhuriGSaraswatVAEndoscopic ultrasonographic evaluation of the rectum in cirrhotic portal hypertensionGastrointest Endosc1993396356408224684

- YachhaSKDhimanRKGuptaRGhoshalUCEndosonographic evaluation of the rectum in children with extrahepatic portal venous obstructionJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr1996234384418956183

- DhimanRKSaraswatVAChoudhuriGSharmaBCPandeyRNaikSREndosonographic, endoscopic, and histologic evaluation of alterations in the rectal venous system in patients with portal hypertensionGastrointest Endosc1999492182279925702

- SatoTHigashinoKToyotaJThe usefulness of endoscopic color Doppler ultrasonography in the detection of perforating veins of esophageal varicesDig Endosc19968180183

- SatoTYamazakiKToyotaJKarinoYOhmuraTAkaikeJObservation of gastric variceal flow characteristics by endoscopic ultrasonography using color DopplerAm J Gastroenterol200810357558018028507

- SatoTYamazakiKAkaikeJEvaluation of the hemodynamics of rectal varices by endoscopic ultrasonographyJ Gastroenterol20064158859216868808

- KomatsudaTIshidaHKonnoKColor Doppler findings of gastrointestinal varicesAbdom Imaging19982345509437062

- SatoTYamazakiKToyotaJKarinoYOhmuraTAkaikeJDiagnosis of rectal varices via color Doppler ultrasonographyAm J Gastroenterol20071022253225817561969

- KatzJARubinRACopeCHollandGBrassCARecurrent bleeding from anorectal varices: successful treatment with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shuntAm J Gastroenterol199388110411078317414

- ShibataDBrophyDPGordonFDTransjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for treatment of bleeding ectopic varices with portal hypertensionDis Colon Rectum1999421581158510613477

- FantinACZalaGRistiBDebatinJFSchopkeWMeyenbergerCBleeding anorectal varices: successful treatment with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS)Gut1996389329358984036

- WangMDesiganGDunnDEndoscopic sclerotherapy for bleeding rectal varices: a case reportAm J Gastroenterol1985807797803876025

- LevineJTahiriABanerjeeBEndoscopic ligation of bleeding rectal varicesGastrointest Endosc1993391881908495844

- FirooziBGamagarisZWeinshelEHBiniEJEndoscopic band ligation of bleeding rectal varicesDig Dis Sci2002471502150512141807

- SatoTYamazakiKToyotaJKarinoYOhmuraTSugaTTwo cases of rectal varices treated by endoscopic variceal ligationDig Endosc1999116669

- ObaraKSakamotoHKasukawaRPrevention of recurrence and rebleeding of esophageal varices with a new method of sclerotherapy -EO-AS combination method followed by mucosal fibrosis with AS-Dig Endosc1990212571263

- ShudoRYazakiYSakuraiSUenishiHYamadaHSugawaraKEndoscopic variceal ligation of bleeding rectal varices: a case reportDig Endosc200012366368

- SatoTYamazakiKToyotaJKarinoYOhmuraTSugaTThe value of the endoscopic therapies in the treatment of rectal varices: a retrospective comparison between injection sclerotherapy and band ligationHep Res200634250255

- ShudoRYazakiYSakuraiSCombined endoscopic variceal ligation and sclerotherapy for bleeding rectal varices associated with primary biliary cirrhosis: a case showing a long-lasting favorable responseGastrointestinal Endosc200153661665