Abstract

Background:

Crohn’s disease (CD), a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), occurs in genetically susceptible individuals who develop aberrant immune responses to endoluminal bacteria. Recurrent inflammation increases the risk of several complications. Despite use of a traditional “step-up” therapy with corticosteroids and immunomodulators, most CD patients eventually require surgery at some time in their disease course. Newer biologic agents have been remarkably effective in controlling severe disease. Thus, “top-down,” early aggressive therapy has been proposed to yield better outcomes, especially in complicated disease. However, safety and cost issues mandate the need for careful patient selection. Identification of high-risk candidates who may benefit from aggressive therapy is becoming increasingly relevant. Serologic and genetic markers of CD have great potential in this regard. The aim of this review is to highlight the clinical relevance of these markers for diagnostics and prognostication.

Methods:

A current PubMed literature search identified articles regarding the role of biomarkers in IBD diagnosis, severity prediction, and stratification. Studies were also reviewed on the presence of IBD markers in non-IBD diseases.

Results:

Several IBD seromarkers and genetic markers appear to be associated with complex CD phenotypes. Qualitative and quantitative serum immune reactivity to microbial antigens may be predictive of disease progression and complications.

Conclusion:

The cumulative evidence provided by serologic and genetic testing has the potential to enhance clinical decision-making when formulating individualized IBD therapeutic plans.

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a prevalent chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) marked by heterogeneous symptoms indicative of an underlying inflammatory process. The hallmark pathology of CD is chronic transmural inflammation, but the phenotypic spectrum varies greatly both in location and behavior (ie, stricturing or penetrating phenotypes).Citation1 As the disease progresses, persisting inflammation may lead to penetration and strictures, perhaps culminating in medically refractory disease requiring multiple hospitalizations and surgical intervention.Citation2–Citation4 The traditional treatment paradigm includes a “step-up” approach of corticosteroids and immunomodulators, with or without biologic agents as severity progresses or patients fail to respond.Citation5–Citation7 Whereas this approach may be effective in the near term,Citation8–Citation10 it may not prevent overall disease progression.Citation11–Citation13 Within 10 years of diagnosis, more than half of CD patients still require surgical resection within 20 years,Citation14 approximately 50%–70% of CD patients develop a stricturing or penetrating intestinal complication,Citation2,Citation15 and the cumulative risk of hospitalization rises to nearly 80%.Citation16 Risk of hospitalization is greatest within the first year after diagnosis of CD (32%–83% of patients), with the annual incidence of hospitalizations remaining steady at 20% over the next 5 years.Citation16,Citation17

“Top-down” therapy,Citation7,Citation18 with the earlier introduction of biologic agents such as antitumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNF-α) antibodies, has demonstrated high rates of remission and mucosal healing.Citation19–Citation23 However, the top-down approach is not appropriate for all patients, as not all of them will develop complicated disease.Citation2,Citation12,Citation16 Early use of immuno-suppressants or biologics soon after diagnosis may increase the risks, including malignancies and infections.Citation7,Citation18 The high costs of these therapiesCitation24,Citation25 also prohibit top-down therapy as a universal approach.Citation7 Therefore, the ability to identify patients at risk for developing a complicated disease course is critical to the effective use of targeted top-down strategies.

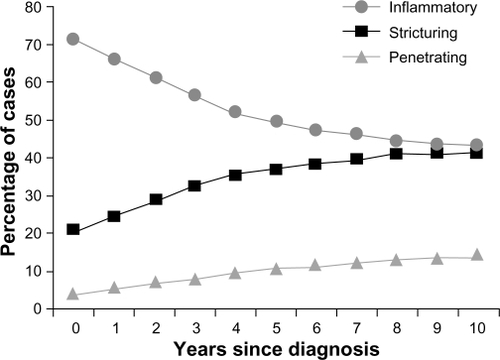

Clinical and nonserologic predictors of disease course

Clinical features have some predictive value for prognosis in CD, but their interpretation remains problematic. Studies have shown that an initial requirement for steroids, young age at diagnosis, presence of small bowel, and/or perianal disease at diagnosis, and cigarette smokingCitation26–Citation28 are associated with an adverse prognosis. However, factors such as referral bias,Citation29 varying definitions of adverse outcomes, and varying prior disease treatments in these studies complicate the prognosis and make predictions difficult for the individual CD patient. Clinical phenotyping issues remain complex; ongoing efforts are being made to standardize a clinical classification scheme for IBD.Citation30 Disease localization may be comparable only at the time of diagnosis, since CD behavior evolves over time. Vernier-Massouille et alCitation31 showed a convergence in rates of CD subtypes, with inflammatory (decreasing prevalence) and stricturing (increasing prevalence) disease over 10 years of follow-up after diagnosis (). Most studies suggest that ileal disease is an independent predictor of adverse outcomes, particularly the need for early surgery.Citation29,Citation32–Citation34 While some clinical features do show associations with adverse prognosis, they are usually described retrospectively, and many features lack standardization. The resulting heterogeneity leads to significant difficulty in using these clinical data for creating therapeutic algorithms in CD.Citation35

Figure 1 Crohn’s disease phenotypic behavior over time, according to Montreal classification at diagnosis and follow-up in 404 pediatric patients. Dramatic changes occurred in the proportion of disease behavior subgroups – from inflammatory nonpenetrating, nonstricturing disease (B1) to stricturing (B2) or penetrating disease (B3) (P < 0.01).

Copyright © 2004, Elsevier. Reproduced with permission from Vernier-Massouille et al.Citation31

Inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), fecal calprotectin, and fecal lactoferrin may be useful in differentiating active IBD from inactive IBD and other gastrointestinal disorders,Citation36 as well as measuring response to various treatments.Citation37 Pretreatment CRP levels have shown utility in predicting treatment response to anti-TNF-α agents in CD in some but not all studies.Citation20,Citation38 The value of CRP as a pretreatment predictor of severe disease remains mostly unknown. Henriksen et alCitation39 found a CRP > 53 mg/L at diagnosis to be predictive of a high risk of surgery (82%) after 5 years in patients with ileal disease (odds ratio [OR] 6.0; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1–31.9), L1 according to the Vienna classification. Although the predictive value of an elevated CRP is suggested in this subset (∼30% of those with L1 classification),Citation39 the sensitivity and specificity of CRP in CD are modest overall. Fecal calprotectin is a natural antibiotic, cytoplasmic protein released into the colonic lumen by activated polymorphonuclear neutrophil cells and/or monocyte-macrophages during cell death. Fecal calprotectin levels are elevated in active IBD. Lactoferrin, similar to calprotectin, is a glycoprotein component of polymorphonuclear neutrophil granules whose concentrations become elevated in feces during an acute mucosal inflammatory response. Four fecal markers of inflammation – calprotectin (PhiCal™ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] test), lactoferrin (IBD-SCAN™ ELISA test), the Hexagon OBTI (immunochromatographic test for detection of human hemoglobin), and LEUKO-TEST (lactoferrin latex-agglutination test) – were evaluated to discriminate irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) from IBD in a prospective study.Citation40 Accuracy was similar with both fecal lactoferrin and fecal calprotectin assays (∼90%), but these tests do not differentiate between various types of inflammatory colitides (ie, diverticulitis, infectious or ischemic colitis). These findings have been replicated.Citation36 Fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin outperform serum CRP or the clinical Crohn’s disease activity index at correlating with endoscopic levels of inflammation (Spearman’s r = 0.729 and 0.773, respectively; P < 0.001), especially colonic inflammation.Citation41 In clinical practice, these tests can be used to differentiate between IBD and IBS or to corroborate clinical flare-ups.

CD-specific serologic and genetic markers

Serologic markers in IBD: role of familial studies

Subsets of IBD patients may have abnormal immune responses to various microbial antigens.Citation42,Citation43 Antibodies to Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ASCA) occur in 50%–70% of CD patients.Citation44 The pathophysiological associations of seromarkers with IBD subtypes are supported by familial studies. Atypical antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are associated with ulcerative colitis (UC) in approximately 70% of patients,Citation44 although familial studies do not suggest that ANCA has genetic underpinnings. Papo et alCitation45 and Folwaczny et alCitation46 both found no increase in ANCA prevalence among unaffected relatives of IBD patients (∼3%–5%). Perinuclear ANCA (pANCA) was subsequently associated with Crohn’s colitis.Citation47

In contrast, ASCA has shown strong familial associations, suggesting its primary role as a stable biomarker in CD. Sendid et alCitation48 found 20% of unaffected relatives were ASCA-positive in CD families versus less than 1% of unaffected relatives in control families. A Belgian study also found similar results (21%)Citation49 but showed that ASCA is not associated with any alteration in intestinal permeability. An Italian study demonstrated elevated ASCA (∼25%) in unaffected relatives of IBD patients, which included purely UC-affected families.Citation50 These investigators concluded there may be a primary genetic influence on ASCA status in IBD families. The possible genetic underpinnings of ASCA in CD are complex. An IBD twin study found only a 5% seroprevalence of ASCA among 20 unaffected (discordant) monozygotic twins with a CD sibling, versus 26% among 27 discordant dizygotic twins. This suggests the importance of shared environmental factors in familial CD.Citation51 However, there still may be a genetic component to ASCA. Seibold et alCitation52 showed that ASCA positivity is associated with mutations in the mannan-binding lectin (MBL) gene that result in MBL deficiency. The physiologic role of MBL includes immune recognition of yeasts and other mannose-expressing pathogens.Citation53 Hence, it may be that ASCA seroreactivity occurs when such pathogens are able to penetrate a permeable intestinal barrier, especially in the setting of MBL deficiency.Citation53 Newer IBD markers (described below) have also shown increased familial expression,Citation54 particularly for CD.

A natural question that follows from familial ASCA is whether ASCA presence positively predisposes to future CD development. The literature on this issue is sparse. One study of 102 ASCA-positive first-degree relatives of IBD patients revealed a less than 2% cumulative incidence of IBD over 7 years.Citation55 In a nonfamilial study, Israeli et alCitation56 found 31% ASCA seropositivity before CD diagnosis in military recruits. An additional 23% of CD patients seroconverted after CD diagnosis, and none of the 95 non-IBD controls were ASCA-positive over the same 38-month median follow-up. Prospective studies would be most informative in this regard.

IBD diagnostics: serologic markers as a screening or diagnostic tool

If seromarkers such as ASCA do precede CD development in as many as one-third of individuals, the positive predictive value (PPV) of the test becomes a relevant issue. Several recent studies have shed light on the spectrum of non-IBD diseases demonstrating ASCA phenomena ().Citation57–Citation65 Data for newer IBD markers are not yet available, and clinicians using serologic markers in the evaluation of IBD should be aware of this. ASCA was originally reported as an antibody to the nonpathogenic yeast S. cerevisiae in CD.Citation43,Citation66 However, the clinically relevant yeast Candida albicans also expresses ASCA epitopes under conditions favoring their virulence; a study from the ASCA-pioneering group in Lille, France,Citation57 confirmed that 100% of patients with systemic candidiasis have acute ASCA titers above cutoff values considered significant in CD. However, this does not preclude the role of ASCA in CD. Candida albicans may be of greater relevance to CD than S.cerevisiae, which has never been considered pathogenic in CD. The same groupCitation57 confirmed that C. albicans is an immunogen for ASCA in CD and is more prevalent in healthy relatives of patients with CD.Citation67 Bacterial infections and other chronic diseases may also generate ASCA positivity in some individuals ().Citation58 Rates of 21%–44% seropositivity have been reported in cystic fibrosis. Bacterial infection was suspected of playing a role in this context.Citation59,Citation60 Intestinal tuberculosis, highly prevalent in many areas of the world, may be difficult to clinically or endoscopically distinguish from CD.Citation68 Makharia et alCitation61 reported seropositivity rates of 43% for immunoglobulin A (IgA) and 47% for ASCA in Indian patients with intestinal tuberculosis, rates that did not differ from those in CD patients. Noninfectious diseases considered in a differential diagnosis of IBD may also demonstrate ASCA phenomena. For example, ASCA titers may be elevated in untreated celiac disease and disappear completely after introducing a gluten-free diet. This suggests that abnormal intestinal permeability plays an important role in ASCA generation, as well as for other antibodies in celiac disease.Citation62 ASCA positivity may also reflect a phenotypic continuum between ulcerative jejunitis, celiac disease, and classical CD. Occasionally, clinicians will encounter patients with IBD or suspected IBD, or with associated diseases such as ankylosing spondylitis or rheumatoid arthritis. In these settings, ASCA has been shown to be nonpredictive of occult IBD.Citation69 In addition, pANCA has been associated with autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) type 1, particularly in men and in those AIH-1 patients with smooth muscle antibody of the anti-actin type.Citation70 Therefore, caution is required when interpreting positive tests in such patients, particularly those without gastrointestinal symptoms. Testing for ASCA alone may have limited usefulness in predicting CD. Furthermore, there is clinical overlap of ASCA in UC.

Table 1 Seroprevalence of ASCA positivity, IgA and IgG in non-IBD disease

These limitations have led to the development of serologic marker combinations in panels to increase their predictive values ().Citation71–Citation76 Sandborn and colleaguesCitation77 reported a PPV of 86% for CD with the ASCA-positive/ANCA-negative combination. Similarly, Peeters et alCitation78 reported a PPV of 91% for this combination. The predictive value is increased by testing ASCA for both IgA and IgG (immunoglobulin G) subfractions.Citation79 However, a meta-analysis of more than 60 ASCA and ANCA studies in IBDCitation80 showed a modest overall sensitivity of the ASCA-positive/ANCA-negative combination for CD (55%) ().Citation44,Citation78,Citation80–Citation86 Several novel bacterial antigens in CD have been identified as potentially useful in serologic testing. Approximately 55% of CD patients test positive for antibodies to Escherichia coli outer membrane porin C (anti-OmpC)Citation87 and for antibodies to a bacterial sequence derived from Pseudomonas fluorescens (anti-I2). Reactivity to CBir1 flagellin, a colitogenic antigen of the enteric flora in C3H/HeJBir mice strain, is highly prevalent (50%) in CD.Citation88 In addition, anti-CBir1 is detected in patients who are nonreactive to the ASCA, OmpC, I2, and ANCA antigens.Citation89 Recently, a class of antibodies called antiglycans have been shown to be prevalent in CD.Citation90 These homogeneous antibodies are directed against carbohydrate moieties on cell surfaces of erythrocytes, immune cells, and microorganisms.Citation90

Table 2 Summary of seromarker characteristics in IBD

Investigators have sought to define specific patterns of reactivity with serologic biomarkers. Such patterns may better distinguish CD from UC or further characterize patients with indeterminate colitis, possibly into a CD or UC diagnosis. Computer algorithm modeling of clinical pattern recognition has been developed to facilitate pattern recognition.Citation80,Citation87,Citation91 For example, the presence of anti-CBir1 and pANCA antibodies among CD patients can help to distinguish between UC and a UC-like CD phenotype.Citation89 In addition, when combined with ASCA and pANCA testing, anti-OmpC and anti-I2 antibodies can help identify up to 84% of patients with CD; this yield drops to 54% when ASCA is considered alone.Citation87

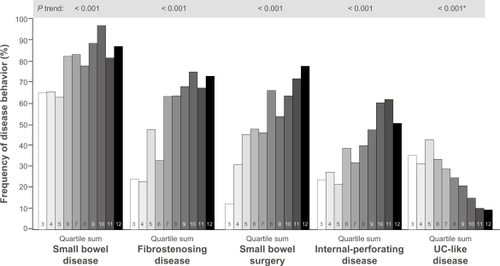

IBD prognostics: individual serologic markers and CD disease behavior

While initially used for diagnostic purposes, serologic panels are more useful in clinical practice for their prognostic information. While each serologic marker is associated with some form(s) of complicated disease behavior, a qualitative response to multiple markers is more predictive of a severe course in CD. Studies in CD have correlated ASCA reactivity with increased risk of surgery within 3 years of diagnosis,Citation92 small bowel disease location,Citation93 early age at diagnosis, and a complicated disease course.Citation94 Additional CD studies have linked pANCA levels to UC-like disease behaviorCitation47,Citation94 and a lack of fibrostenosing/penetrating disease.Citation93,Citation94 In UC patients undergoing ileal pouch anal anastomosis, high levels of pANCA before proctocolectomy are associated with development of chronic pouchitis.Citation95,Citation96 The next generation of serologic markers after ASCA and pANCA have been associated with an aggressive disease course in CD (). Anti-OmpC and anti-I2 are associated with fibrostenosing and internal-perforating disease behavior as well as small bowel surgery.Citation50,Citation71,Citation73 Additionally, multivariate logistic regression analysis has shown that these two markers are independently associated with a complicated CD phenotype and/or surgery.Citation71 Patients who express anti-CBir1 are nearly twice as likely to develop small bowel disease and complicated phenotypes such as fibrostenosis and internal-perforating disease.Citation89 A recent study reported that anti-CBir1 can be predictive of the development of pouchitis after ileal pouch anal anastomosis in pANCA-positive patients.Citation96

Table 3 Studies of serologic panels in predicting disease phenotype in Crohn’s disease

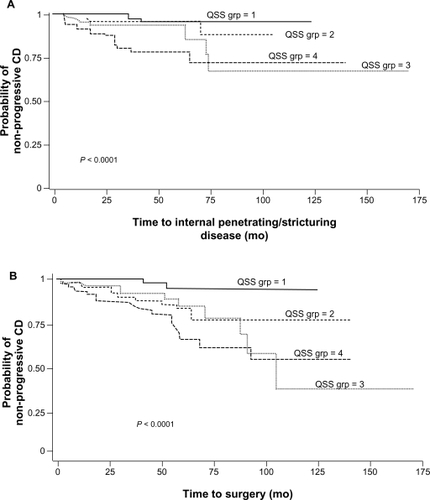

Serologic panels and disease behavior

An association between severe, complicated CD and high-level immune responses was confirmed in multiple studies analyzing quantitative antibody levels in panels of serologic markers (). In 2004, Mow et alCitation71 associated cumulative antibody responses to I2 and OmpC with distinct disease phenotypes. Sera from 303 CD patients were analyzed for anti-I2, anti-OmpC, and ASCA. Quartile scores of 1–4 were assigned to the individual antigens based on antibody levels measured; a quartile sum score (range 3–12) was derived for each patient to represent the cumulative quantitative immune response to all four antigens.Citation71 Patients with a qualitative antigen reactivity to I2, OmpC, and oligomannan (ASCA) were more likely to develop complicated disease (fibrostenosing and internal-perforating disease) and require small bowel surgery than patients expressing fewer than three antibodies (P ≤ 0.001).Citation71 Quartile sum score analysis suggested that the magnitude of antibody responses to I2, OmpC, and oligomannan was also associated with complicated small bowel disease ().Citation71 In a similar study, Arnott et al also found that the presence and magnitude of anti-OmpC, anti-I2, and ASCA were significantly associated with complicated disease ().Citation72 Papadakis et alCitation73 examined a serologic panel that included anti-CBir1 in addition to ASCA, anti-I2, and anti-OmpC to predict disease severity in 731 patients with CD. Quartile sum scores for this cohort revealed that increasing levels of reactivity to all four antigens were associated with fibrostenosing and internal-perforating disease.Citation73 When added to the quantitative responses to the other three antigens, anti-CBir1 reactivity enhanced the discrimination of complicated disease phenotypes (fibrostenosing or internal penetrating), small bowel involvement, and UC-like behavior.Citation73 Dubinsky et alCitation74,Citation75 conducted the first two prospective studies in pediatric CD patients that demonstrated a relationship between serologic responses and aggressive disease behavior. In the first study in 196 patients tested for anti-I2, anti-OmpC, ASCA, and anti-CBir1, the frequency of complicated disease behavior increased as the number of immune responses increased; the presence of four positive markers was associated with the highest likelihood of aggressive disease ().Citation74 These initial findings were confirmed in another, larger study of 796 pediatric CD patients using ASCA, anti-OmpC, and anti-CBir1.Citation75 The frequency of internal-penetrating disease, stricturing disease, and surgery increased substantially with both the number and magnitude of immune responses.Citation75 Kaplan–Meier estimates for time to development of internal-penetrating/stricturing disease and CD-related surgery by quartile sum scores are presented in .Citation75 In both instances, time to adverse outcome (complex disease, surgery) is generally shorter in those patients with the highest quartile scores, whereas those in the lowest quartile have a very high probability of remaining free of adverse outcomes over long periods. The prospective design of these studies supports the use of serologic testing to predict future disease behavior.Citation74,Citation75

Figure 2 Frequency of complicated small bowel disease, as represented by antibody quartile sum score. A summation score of 3–12 for antibody titers toward I2, OmpC, and ASCA was calculated and categorized into quartiles (QSS). Patients with higher sum scores had greater frequency of complicated course (fibrostenosing, penetrating, or small bowel disease, or need for surgery).

Copyright © 2008, Elsevier. Reproduced with permission from Mow et al.Citation71

Abbreviations: ASCA, antibodies to Saccharomyces cerevisiae; OmpC, outer membrane porin C; QSS, quartile sum score; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Figure 3 Kaplan–Meier plot estimates for internal-penetrating/stricturing disease and need for bowel surgery by QSS of antibody titers toward I2, OmpC, and ASCA among CD patients. The figure depicts a higher probability of maintaining a simple, noncomplicated disease course during prospective follow-up, among those patients who fall into the lower QSS groups (QSS groups 1 and 2) (A). Conversely, half of the patients in QSS group 3 required surgery within 100 months of follow-up (B).

Copyright © 2008, Elsevier. Reproduced with permission from Dubinsky et al.Citation75

Future directions

Genetic markers in assessing aggressive disease behavior

The identification of genetic markers in CD is an active area of research.Citation7,Citation71,Citation97–Citation101 The nucleotide oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2), also known as caspase-activating recruitment domain 15 (CARD15) at the IBD1 locus is the first major susceptibility gene described for CD.Citation102–Citation104 Three major-effect NOD2/CARD15 variants have been found to account for the majority (81%) of over 30 such allelic mutations in CD; the mutations R702W, G908R, and 1007fs being designated as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) 8, 12, and 13, respectively.Citation100,Citation102 Data from across the general population suggest a low penetrance for NOD2/CARD15 mutations. However, among CD patients, each of the three SNPs has been shown to be independently associated with development of symptoms, with the greatest risk conferred by the SNP13 mutant allele and in those with multiple mutations.Citation104–Citation106 The NOD2/ CARD15 variant genotypes have been associated with severe CD phenotypes.Citation97,Citation98,Citation100,Citation101,Citation107,Citation108 Abreu et alCitation97 compared NOD2/ CARD15 genotypes to serum immune markers, disease behavior, and disease location in two consecutive cohorts of CD patients (). Multivariate analysis showed a significant association between the NOD2/CARD15 variants and fibrostenosing disease (OR 2.8; 95% CI 1.3–6.0; P = 0.011).Citation97 In addition, the risk of developing fibrostenosing disease was greatest among carriers of two mutations (OR 7.4; 95% CI 1.9–28.9; P = 0.004). Similar findings have been observed in large EuropeanCitation100,Citation107 and AmericanCitation71,Citation98 cohorts.

Table 4 Significant individual associations of antibody responses and NOD2/CARD15 genotype with Crohn’s disease phenotypesCitation71,Citation89,Citation97

Genome-wide association studies have identif ied approximately 71 CD-associated gene susceptibility loci, with potentially many more genes.Citation104 Some of these have been assessed for their relationship to CD phenotype and disease course. Weersma et alCitation109 examined genetic variants, including NOD2/CARD15, Drosophilia discs homolog 5 (DRG5), autophagy-related 16-like 1 gene (ATG16L1), and the interleukin 23 receptor gene (IL23R). Results showed that an increase in the number of allelic variants or genotypes was associated with an increased risk of developing CD and having a complicated disease course.Citation109 These findings suggest that it is possible to assess a given patient’s genetic profile to determine risk of complicated disease.

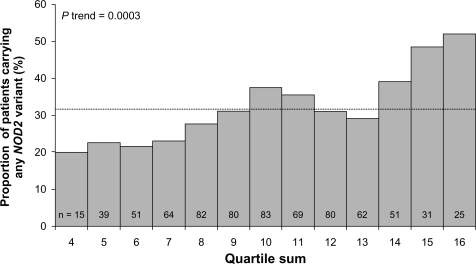

Synergism between serologic phenotypes and genetic variants

Emerging data from studies of familial expression of ASCA, anti-OmpC, and other IBD serologic markers suggest that genetic mutations lead to alterations in the expression of antibodies to microbial antigens.Citation49,Citation54,Citation99,Citation101,Citation110–Citation112 Anti-CBir1 and ASCA expression were linked to NFKB1 haplotypes and subsequently to reductions in NF-kB activation, thus describing another link between innate and adaptive immunity in IBD.Citation113 Studies have not always concurred regarding the association between NOD2/CARD15 polymorphisms and seromarkers in IBD.Citation99,Citation110,Citation114 However, NOD2/CARD15 variants seem to be more common in patients testing positive for multiple serologic markers, including those with high antibody levels (elevated quartile sum scores) ().Citation101,Citation111 Ippoliti et alCitation76 determined that a combination of altered innate and adaptive immune responses act synergistically to increase the development of complicated CD, particularly fibrostenosing disease. After grouping patients by serologic quartile sum scores of 4–6, 7–9, 10–13, and 14–16 and subdividing by the presence or absence of NOD2/CARD15, they calculated ORs for developing fibrostenotic disease (). The ORs were significantly greater among patients with the presence of NOD2 variants than those without. The ORs were also increased with higher quartile sum scores.

Figure 4 Frequency of carriage of NOD2/CARD15 variant relative to semiquantitative antibody reactivity, as represented by quartile sum (range 4–16). The dotted line represents the mean 31.8% frequency of carriage of at least one NOD2/CARD15 variant, across the entire cohort.

Copyright © 2007, Elsevier. Reproduced with permission from Devlin et al.Citation111

Table 5 Demonstration of synergism between NOD2 variants and antibody levels in fibrostenosis

Future diagnostic tests may quantitatively assign a risk probability for severe disease by using algorithms that analyze these serologic and genetic biomarkers. A new CD prognostic test was recently made available. This serogenetic panel is composed of seven assays for nine markers, including six serologic biomarkers, specifically ASCA-IgA, ASCA-IgG, anti-OmpC, anti-I2, anti-CBir1, and pANCA. In addition, the test recognizes three NOD2 gene variants (SNP8, SNP12, and SNP13). The prognostic panel calculates probability of complications curve based on antibody quartile sum scores and NOD2/CARD15 mutation status. The results are then analyzed by a logistic regression algorithm to quantify the likelihood that a patient will progress to a complicated CD phenotype. The test output is a probability score reflecting the likelihood of disease progression to complications.Citation115

Current research in identifying predictors of treatment response

Another area of growing interest that has potential to contribute to a personalized approach in CD is the prediction of response to medical therapies, particularly biologic agents.Citation116,Citation117 Some clinical features have been shown to influence response to infliximab. In a prospective study in 74 CD patients, Arnott et alCitation116 found that smoking significantly influences response to infliximab, with smokers less likely to respond at 4 weeks (OR 0.24; 95% CI 0.06–0.91; P = 0.035) and more likely to relapse at 1 year (relative risk 3.2; P = 0.0026) than nonsmokers. Other factors that had predictive value were colonic disease, which increased the likelihood of response at 4 weeks nearly five-fold, and concomitant immunosuppression, which was associated with reduced risk of relapse at 1 year.Citation116 In addition, detectable trough serum concentrations of infliximab (irrespective of antibody formation) have been shown to be associated with higher rates of clinical and endoscopic remission.Citation117 Investigators have begun to explore the relationship of various serologic markers with response to medical therapies. Sandborn et alCitation118 found an increased frequency of pANCA positivity in patients with left-sided UC that was resistant to oral and rectal 5-aminosalicylates and corticosteroids. In 2004, Mow et alCitation119 reported the results of a small pilot study that suggested serum reactivity to microbial antigens, particularly to OmpC and I2, would help to predict response to combination antibiotic therapy. Finally, the utility of serologic markers in predicting response to biologic agents was explored, with one study demonstrating an insignificant trend toward lower response rates to infliximab with the pANCA-positive/ ASCA-negative combination in CDCitation120 and another associating the same combination with suboptimal early clinical response to infliximab in UC (OR 0.40; 95% CI 0.16–1.00; P = 0.049).Citation121 Investigators developed an algorithm to predict response to infliximab using a previous cohort of 287 patients with inflammatory or fistulizing CD and combining key clinical predictors (ie, age <40 years, concurrent use of immunosuppressants, disease location, and CRP levels) and pharmacogenetic data of three apoptotic SNPs (Fas ligand-843 C/T, Fas-670 G/A, and Caspase9 93 C/T).Citation122 The algorithm for inflammatory disease enabled prediction of response rates of 21.4%–100% and remission rates of 15.8%–85.7%, while the algorithm for fistulizing disease enabled prediction of response rates of 46.6%–100% and remission rates of 20%–57.6%.Citation122 Recently, Dubinsky et alCitation123 indicated that a combination of a phenotype, serotype, and genotype is the best predictive model of nonresponse to anti-TNF-α agents in pediatric patients. Specifically, the most predictive model included the presence of three novel “pharmacogenetic” loci, the IBD-associated loci BRWD1, pANCA, and a UC diagnosis (P < 0.05 for all). The relative risk of nonresponse increased 15 times as the number of risk factors increased from 0–2 to ≥3 (P < 0.0001).Citation123

Impact of predictive factors

Current evidence suggests that a combination of clinical findings (eg, smoking) and the measurement of immune responses with serologic testing – in combination with genetic testing – can help to predict disease behavior.Citation124 Moreover, evidence shows that these tools may be used to stratify patients at the time of diagnosis on the basis of their risk of developing aggressive disease.Citation124 Screening for NOD2/CARD15 genetic variants early in the patient’s disease course may also provide additional evidence to suggest a patient’s likelihood of disease progression and allow clinicians to tailor therapeutic strategies based on the aggressiveness of IBD subtype.Citation124 Early aggressive intervention would then be delivered to high-risk patients and less intensive therapies to those more likely to have a benign disease course. While serogenetic testing for diagnosing disease, predicting disease course, or determining treatment optionsCitation5 is not routinely used, clinical practice guidelines may ultimately evolve to include a therapeutic algorithm recommending use of top-down therapy in patients with or at risk for complicated disease behavior, as assessed by the combination of clinical characteristics and serologic and genetic findings.Citation11 Furthermore, the identification of new pathogenetic treatments, including cytokines (eg, IL-23, IL-17), diapedesis inhibitors (eg, natalizumab, vedolizamab), and chemokine receptor antagonists (eg, CCX282-B), offer the promise of targeted biologic therapies. Future generations of IBD serologic profiles/genetic testing can be anticipated to play a role in identifying optimal biologic family therapeutic options.

Conclusion

Given the evidence to support the use of a top-down treatment approach, it is imperative to identify patients who are most likely to benefit from this strategy. Although clinical characteristics alone can help to predict a complicated disease course, these features lack the accuracy to effectively influence therapeutic decisions. Information gained from serologic testing, both qualitatively and quantitatively, can assist in determining the likelihood of a complicated CD. This personalized approach may be further improved with the incorporation of knowledge regarding NOD2/CARD15 and other novel CD-associated genetic polymorphisms. Growing evidence suggests that the aberrant IBD innate immunity reflects underlying genetic determinants in CD patients. The subsequent maladaptive auto-immune response is in turn reflected by the presence of IBD serologic markers. Taken together, the patient’s clinical and serogenetic profile may be used to inform clinicians regarding a patient’s prognostic risk and help guide treatment decisions to alter the future natural history of CD now.

Disclosure

Technical assistance during the development of this manuscript was provided with funding support from Prometheus Laboratories, Inc. Cyrus P Tamboli has no relevant disclosures. David B Doman discloses that he is on the speakers’ bureau of Prometheus Laboratories, Abbott Pharmaceuticals, and Salix Pharmaceuticals. Amar Patel discloses that at the time of the writing of the draft, he was an employee of Peloton Advantage, which received funding support from Prometheus Laboratories.

References

- GascheCScholmerichJBrynskovJA simple classification of Crohn’s disease: report of the Working Party for the World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998Inflamm Bowel Dis20006181510701144

- ThiaKSandbornWHarmsenWZinmeisterAThe evolution of Crohn’s disease (CD) behavior in a population-based cohort [abstract 1135]Am J Gastroenterol2008103Suppl 5S443S444

- RutgeertsPGeboesKVantrappenGKerremansRCoenegrachtsJLCoremansGNatural history of recurrent Crohn’s disease at the ileocolonic anastomosis after curative surgeryGut19842566656726735250

- SilversteinMDLoftusEVSandbornWJClinical course and costs of care for Crohn’s disease: Markov model analysis of a population-based cohortGastroenterology19991171495710381909

- LichtensteinGRHanauerSBSandbornWJfor the Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of GastroenterologyManagement of Crohn’s disease in adultsAm J Gastroenterol2009104246548319174807

- CarterMJLoboAJTravisSPGuidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adultsGut200453Suppl 5V1V1615306569

- HanauerSBPositioning biologic agents in the treatment of Crohn’s diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200915101570158219309716

- KaneSVSchoenfeldPSandbornWJTremaineWHoferTFeaganBGSystematic review: the effectiveness of budesonide therapy for Crohn’s diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther20021681509151712182751

- PearsonDCMayGRFickGHSutherlandLRAzathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in Crohn disease. A meta-analysisAnn Intern Med199512321321427778826

- SummersRWSwitzDMSessionsJTJrNational Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study: results of drug treatmentGastroenterology1979774 Pt 284786938176

- VermeireSVan AsscheGRutgeertsPReview article: altering the natural history of Crohn’s disease – evidence for and against current therapiesAliment Pharmacol Ther200725131217229216

- FaubionWAJrLoftusEVJrHarmsenWSZinsmeisterARSandbornWJThe natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based studyGastroenterology2001121225526011487534

- CosnesJNion-LarmurierIBeaugerieLAfchainPTiretEGendreJPImpact of the increasing use of immunosuppressants in Crohn’s disease on the need for intestinal surgeryGut200554223724115647188

- DhillonSLLoftusEVTremaineWJThe natural history of surgery for Crohn’s disease in a population-based cohort from Olmsted County, Minnesota [abstract 825]Am J Gastroenterol2005100SupplS305

- CosnesJCattanSBlainALong-term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn’s diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis20028424425012131607

- Peyrin-BirouletLLoftusEVJrColombelJFSandbornWJThe natural history of adult Crohn’s disease in population-based cohortsAm J Gastroenterol2010105228929719861953

- MunkholmPLangholzEDavidsenMBinderVDisease activity courses in a regional cohort of Crohn’s disease patientsScand J Gastroenterol19953076997067481535

- D’HaensGRTop-down therapy for IBD: rationale and requisite evidenceNat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol201072869220134490

- SchreiberSReinischWColombelJFEarly Crohn’s disease shows high levels of remission to therapy with adalimumab: sub-analysis of CHARM [abstract 985]Gastroenterology2007132Suppl 1A147

- SandbornWJColombelJFPanesJScholmerichJMcConnellJSchreiberSHigher remission and maintenance of response rates with subcutaneous monthly certolizumab pegol in patients with recent-onset Crohn’s disease: data from PRECiSE 2 [abstract 1109]Am J Gastroenterol2006101S454S455

- SandbornWJRutgeertsPReinischWSONIC: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial comparing infliximab and infliximab plus azathioprine in patients with Crohn’s disease naive to immunomodulators and biologic therapy [late-breaking abstract 29]Am J Gastroenterol2008103Suppl 1S423

- D’HaensGBaertFVan AsscheGEarly combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease: an open randomised trialLancet2008371961366066718295023

- MarkowitzJGrancherKKohnNLesserMDaumFA multicenter trial of 6-mercaptopurine and prednisone in children with newly diagnosed Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology2000119489590211040176

- OllendorfDALidskyLInfliximab drug and infusion costs among patients with Crohn’s disease in a commercially-insured settingAm J Ther200613650250617122530

- BodgerKEconomic implications of biological therapies for Crohn’s disease: review of infliximabPharmacoeconomics200523987588816153132

- BeaugerieLSeksikPNion-LarmurierIGendreJPCosnesJPredictors of Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology2006130365065616530505

- CosnesJCarbonnelFBeaugerieLLe QuintrecYGendreJPEffects of cigarette smoking on the long-term course of Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology199611024244318566589

- CottoneMRosselliMOrlandoASmoking habits and recurrence in Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology199410636436488119535

- SandsBEArsenaultJERosenMJRisk of early surgery for Crohn’s disease: implications for early treatment strategiesAm J Gastroenterol200398122712271814687822

- SilverbergMSSatsangiJAhmadTToward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of GastroenterologyCan J Gastroenterol200519Suppl A53616151544

- Vernier-MassouilleGBaldeMSalleronJNatural history of pediatric Crohn’s disease: a population-based cohort studyGastroenterology200813541106111318692056

- BernellOLapidusAHellersGRisk factors for surgery and postoperative recurrence in Crohn’s diseaseAnn Surg20002311384510636100

- SolbergICVatnMHHoieOClinical course in Crohn’s disease: results of a Norwegian population-based ten-year follow-up studyClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20075121430143818054751

- Romberg-CampsMJDagneliePCKesterADInfluence of phenotype at diagnosis and of other potential prognostic factors on the course of inflammatory bowel diseaseAm J Gastroenterol2009104237138319174787

- DotanIDisease behavior in adult patients: are there predictors for stricture or fistula formation?Dig Dis200927320621119786742

- LanghorstJElsenbruchSKoelzerJRuefferAMichalsenADobosGJNoninvasive markers in the assessment of intestinal inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases: performance of fecal lactoferrin, calprotectin, and PMN-elastase, CRP, and clinical indicesAm J Gastroenterol2008103116216917916108

- SipponenTSavilahtiEKärkkäinenPFecal calprotectin, lactoferrin, and endoscopic disease activity in monitoring anti-TNF-alpha therapy for Crohn’s diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200814101392139818484671

- SandbornWJFeaganBGStoinovSCertolizumab pegol for the treatment of Crohn’s diseaseN Engl J Med2007357322823817634458

- HenriksenMJahnsenJLygrenIC-reactive protein: a predictive factor and marker of inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Results from a prospective population-based studyGut200857111518152318566104

- SchoepferAMTrummlerMSeeholzerPSeibold-SchmidBSeiboldFDiscriminating IBD from IBS: comparison of the test performance of fecal markers, blood leukocytes, CRP, and IBD antibodiesInflamm Bowel Dis2008141323917924558

- SipponenTSavilahtiEKolhoKLNuutinenHTurunenUFarkkilaMCrohn’s disease activity assessed by fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin: correlation with Crohn’s disease activity index and endoscopic findingsInflamm Bowel Dis2008141404618022866

- SaxonAShanahanFLandersCGanzTTarganSA distinct subset of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies is associated with inflammatory bowel diseaseJ Allergy Clin Immunol19908622022102200820

- MainJMcKenzieHYeamanGRAntibody to Saccharomyces cerevisiae (bakers’ yeast) in Crohn’s diseaseBMJ19882976656110511063143445

- Peyrin-BirouletLStandaert-VitseABrancheJChamaillardMIBD serological panels: facts and perspectivesInflamm Bowel Dis200713121561156617636565

- PapoMQuerJCPastorRMAntineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in relatives of patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseAm J Gastroenterol1996918151215158759652

- FolwacznyCNoehlNEndresSPLoeschkeKFrickeHAnti-neutrophil and pancreatic autoantibodies in first-degree relatives of patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseScand J Gastroenterol19983355235289648993

- VasiliauskasEAPlevySELandersCJPerinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in patients with Crohn’s disease define a clinical subgroupGastroenterology19961106181018198964407

- SendidBQuintonJFCharrierGAnti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan antibodies in familial Crohn’s diseaseAm J Gastroenterol1998938130613109707056

- VermeireSPeetersMVlietinckRAnti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA), phenotypes of IBD, and intestinal permeability: a study in IBD familiesInflamm Bowel Dis20017181511233666

- SuttonCLKimJYamaneAIdentification of a novel bacterial sequence associated with Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology20001191233110889151

- HalfvarsonJStandaert-VitseAJarnerotGAnti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies in twins with inflammatory bowel diseaseGut20055491237124315863472

- SeiboldFKonradAFlogerziBGenetic variants of the mannan-binding lectin are associated with immune reactivity to mannans in Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology200412741076108415480986

- MullerSSchafferTFlogerziBMannan-binding lectin deficiency results in unusual antibody production and excessive experimental colitis in response to mannose-expressing mild gut pathogensGut201059111493150020682699

- MeiLTarganSRLandersCJFamilial expression of anti-Escherichia coli outer membrane porin C in relatives of patients with Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology200613041078108516618402

- TorokHPGlasJHollayHCSerum antibodies in first-degree relatives of patients with IBD: a marker of disease susceptibility? A follow-up pilot-study after 7 yearsDigestion2005722–311912316172548

- IsraeliEGrottoIGilburdBAnti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies as predictors of inflammatory bowel diseaseGut20055491232123616099791

- Standaert-VitseAJouaultTVandewallePCandida albicans is an immunogen for anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody markers of Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology200613061764177516697740

- BerlinTZandman-GoddardGBlankMAutoantibodies in nonautoimmune individuals during infectionsAnn N Y Acad Sci2007110858459317894023

- CondinoAAHoffenbergEJAccursoFFrequency of ASCA seropositivity in children with cystic fibrosisJ Pediatr Gastroenterol Nurs20054112326

- LachenalFNkanaKNove-JosserandRFabienNDurieuIPrevalence and clinical significance of auto-antibodies in adults with cystic fibrosisEur Respir J20093451079108519443536

- MakhariaGKSachdevVGuptaRLalSPandeyRMAnti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody does not differentiate between Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosisDig Dis Sci2007521333917160471

- GranitoAZauliDMuratoriPAnti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in coeliac disease before and after gluten-free dietAliment Pharmacol Ther200521788188715801923

- SaklyWMankaiASaklyNAnti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies are frequent in type 1 diabetesEndocr Pathol201021210811420387011

- MuratoriPMuratoriLGuidiMAnti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) and autoimmune liver diseasesClin Exp Immunol2003132347347612780695

- RienteLChimentiDPratesiFAntibodies to tissue transglutaminase and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritisJ Rheumatol200431592092415124251

- SendidBColombelJFJacquinotPMSpecific antibody response to oligomannosidic epitopes in Crohn’s diseaseClin Diagn Lab Immunol1996322192268991640

- Standaert-VitseASendidBJoossensMCandida albicans colonization and ASCA in familial Crohn’s diseaseAm J Gastroenterol200910471745175319471251

- AnandBSDiagnosis of gastrointestinal tuberculosisTrop Gastroenterol19941541791857618199

- HoffmanIEDemetterPPeetersMAnti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae IgA antibodies are raised in ankylosing spondylitis and undifferentiated spondyloarthropathyAnn Rheum Dis200362545545912695160

- ZauliDGhettiSGrassiAAnti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in type 1 and 2 autoimmune hepatitisHepatology1997255110511079141425

- MowWSVasiliauskasEALinYCAssociation of antibody responses to microbial antigens and complications of small bowel Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology2004126241442414762777

- ArnottIDLandersCJNimmoEJSero-reactivity to microbial components in Crohn’s disease is associated with disease severity and progression, but not NOD2/CARD15 genotypeAm J Gastroenterol200499122376238415571586

- PapadakisKAYangHIppolitiAAnti-flagellin (CBir1) phenotypic and genetic Crohn’s disease associationsInflamm Bowel Dis200713552453017260364

- DubinskyMCLinYCDutridgeDSerum immune responses predict rapid disease progression among children with Crohn’s disease: immune responses predict disease progressionAm J Gastroenterol2006101236036716454844

- DubinskyMCKugathasanSMeiLIncreased immune reactivity predicts aggressive complicating Crohn’s disease in childrenClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20086101105111118619921

- IppolitiADevlinSMeiLCombination of innate and adaptive immune alterations increased the likelihood of fibrostenosis in Crohn’s diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis20101681279128520027650

- SandbornWJLoftusEVJrColombelJFEvaluation of serologic disease markers in a population-based cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis20017319220111515844

- PeetersMJoossensSVermeireSVlietinckRBossuytXRutgeertsPDiagnostic value of anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae and antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies in inflammatory bowel diseaseAm J Gastroenterol200196373073411280542

- KleblFHBatailleFHofstadterFHerfarthHScholmerichJRoglerGOptimising the diagnostic value of anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae-antibodies (ASCA) in Crohn’s diseaseInt J Colorectal Dis200419431932414745572

- ReeseGEConstantinidesVASimillisCDiagnostic precision of anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in inflammatory bowel diseaseAm J Gastroenterol2006101102410242216952282

- SolbergICLygrenICvancarovaMPredictive value of serologic markers in a population-based Norwegian cohort with inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200915340641419009607

- FerranteMHenckaertsLJoossensMNew serological markers in inflammatory bowel disease are associated with complicated disease behaviourGut200756101394140317456509

- AshornSHonkanenTKolhoKLFecal calprotectin levels and serological responses to microbial antigens among children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200915219920518618670

- BenorSRussellGHSilverMIsraelEJYuanQWinterHSShortcomings of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Serology 7 panelPediatrics201012561230123620439597

- MorgansternJAShakirTChawlaAIs CBir1 a predictor of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease? [abstract 2]J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr200745E1

- RashidFBechtoldMLPuliSRBraggJDUtility of IBD serology tests: experience of an academic medical centerThe Internet J Gastroenterol2011101

- LandersCJCohavyOMisraRSelected loss of tolerance evidenced by Crohn’s disease-associated immune responses to auto- and microbial antigensGastroenterology2002123368969912198693

- LodesMJCongYElsonCOBacterial flagellin is a dominant antigen in Crohn diseaseJ Clin Invest200411391296130615124021

- TarganSRLandersCJYangHAntibodies to CBir1 flagellin define a unique response that is associated independently with complicated Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology200512872020202815940634

- DotanIFishmanSDganiYAntibodies against laminaribioside and chitobioside are novel serologic markers in Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology2006131236637816890590

- JoossensSReinischWVermeireSThe value of serologic markers in indeterminate colitis: a prospective follow-up studyGastroenterology200212251242124711984510

- ForcioneDGRosenMJKisielJBSandsBEAnti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (ASCA) positivity is associated with increased risk for early surgery in Crohn’s diseaseGut20045381117112215247177

- KleblFHBatailleFBerteaCRAssociation of perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies with Vienna classification subtypes of Crohn’s diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis20039530230714555913

- VasiliauskasEAKamLYKarpLCGaiennieJYangHTarganSRMarker antibody expression stratifies Crohn’s disease into immunologically homogeneous subgroups with distinct clinical characteristicsGut200047448749610986208

- FleshnerPRVasiliauskasEAKamLYHigh level perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) in ulcerative colitis patients before colectomy predicts the development of chronic pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosisGut200149567167711600470

- FleshnerPIppolitiADubinskyMBoth preoperative perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and anti-CBir1 expression in ulcerative colitis patients influence pouchitis development after ileal pouch-anal anastomosisClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20086556156818378498

- AbreuMTTaylorKDLinYCMutations in NOD2 are associated with fibrostenosing disease in patients with Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology2002123367968812198692

- BrantSRPiccoMFAchkarJPDefining complex contributions of NOD2/CARD15 gene mutations, age at onset, and tobacco use on Crohn’s disease phenotypesInflamm Bowel Dis20039528128914555911

- SchoepferAMSchafferTMuellerSPhenotypic associations of Crohn’s disease with antibodies to flagellins A4-Fla2 and Fla-X, ASCA, p-ANCA, PAB, and NOD2 mutations in a Swiss CohortInflamm Bowel Dis20091591358136719253375

- LesageSZoualiHCezardJPCARD15/NOD2 mutational analysis and genotype-phenotype correlation in 612 patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseAm J Hum Genet200270484585711875755

- IppolitiAFDevlinSYangHThe relationship between abnormal innate and adaptive immune function and fibrostenosis in Crohn’s disease patients [abstract 127]Gastroenterology2006130A24A25

- HugotJPChamaillardMZoualiHAssociation of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn’s diseaseNature2001411683759960311385576

- OguraYBonenDKInoharaNA frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s diseaseNature2001411683760360611385577

- FrankeAMcGovernDPBarrettJCGenome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn’s disease susceptibility lociNat Genet201042121118112521102463

- EconomouMTrikalinosTALoizouKTTsianosEVIoannidisJPDifferential effects of NOD2 variants on Crohn’s disease risk and phenotype in diverse populations: a metaanalysisAm J Gastroenterol200499122393240415571588

- YazdanyarSKamstrupPRTybjaerg-HansenANordestgaardBGPenetrance of NOD2/CARD15 genetic variants in the general populationCMAJ2010182766166520371648

- HelioTHalmeLLappalainenMCARD15/NOD2 gene variants are associated with familially occurring and complicated forms of Crohn’s diseaseGut200352455856212631669

- AhmadTArmuzziABunceMThe molecular classification of the clinical manifestations of Crohn’s diseaseGastroenterology2002122485486611910336

- WeersmaRKStokkersPCvan BodegravenAAMolecular prediction of disease risk and severity in a large Dutch Crohn’s disease cohortGut200958338839518824555

- DassopoulosTFrangakisCCruz-CorreaMAntibodies to Saccharomyces cerevisiae in Crohn’s disease: higher titers are associated with a greater frequency of mutant NOD2/CARD15 alleles and with a higher probability of complicated diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis200713214315117206688

- DevlinSMYangHIppolitiANOD2 variants and antibody response to microbial antigens in Crohn’s disease patients and their unaffected relativesGastroenterology2007132257658617258734

- JoossensMVan SteenKBrancheJFamilial aggregation and antimicrobial response dose-dependently affect the risk for Crohn’s diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis2010161586719504613

- TakedatsuHTaylorKDMeiLLinkage of Crohn’s disease-related serological phenotypes: NFKB1 haplotypes are associated with anti-CBir1 and ASCA, and show reduced NF-kappaB activationGut2009581606718832525

- WalkerLJAldhousMCDrummondHEAnti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) in Crohn’s disease are associated with disease severity but not NOD2/CARD15 mutationsClin Exp Immunol2004135349049615008984

- LichtensteinGRBarkenDMEgglestonLA novel algorithm-based approach using clinical parameters, genetic and serological markers to effectively predict aggressive disease behavior in patients with Crohn’s disease [abstract 207]Presented at Digestive Disease WeekNew Orleans, LAMay 1–6, 2010

- ArnottIDMcNeillGSatsangiJAn analysis of factors influencing short-term and sustained response to infliximab treatment for Crohn’s diseaseAliment Pharmacol Ther200317121451145712823146

- MaserEAVillelaRSilverbergMSGreenbergGRAssociation of trough serum infliximab to clinical outcome after scheduled maintenance treatment for Crohn’s diseaseClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20064101248125416931170

- SandbornWJLandersCJTremaineWJTarganSRAssociation of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies with resistance to treatment of left-sided ulcerative colitis: results of a pilot studyMayo Clin Proc19967154314368628021

- MowWSLandersCJSteinhartAHHigh-level serum antibodies to bacterial antigens are associated with antibiotic-induced clinical remission in Crohn’s disease: a pilot studyDig Dis Sci2004497–81280128615387358

- EstersNVermeireSJoossensSSerological markers for prediction of response to anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment in Crohn’s diseaseAm J Gastroenterol20029761458146212094865

- FerranteMVermeireSKatsanosKHPredictors of early response to infliximab in patients with ulcerative colitisInflamm Bowel Dis200713212312817206703

- HlavatyTFerranteMHenckaertsLPierikMRutgeertsPVermeireSPredictive model for the outcome of infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease based on apoptotic pharmacogenetic index and clinical predictorsInflamm Bowel Dis200713437237917206723

- DubinskyMCMeiLFriedmanMGenome wide association (GWA) predictors of anti-TNFalpha therapeutic responsiveness in pediatric inflammatory bowel diseaseInflamm Bowel Dis20091681357136620014019

- DevlinSMDubinskyMCDetermination of serologic and genetic markers aid in the determination of the clinical course and severity of patients with IBDInflamm Bowel Dis200814112512817932968