Abstract

Background

Platinum-doublet, first-line treatment of locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is limited to 4–6 cycles. An alternative strategy used to prolong the duration of first-line treatment and extend survival in metastatic NSCLC is first-line maintenance therapy. Erlotinib was approved for first-line maintenance in a stable disease population following results from a randomized, controlled Phase III trial comparing erlotinib with best supportive care. We aimed to estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness of erlotinib 150 mg/day versus best supportive care when used as first-line maintenance therapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC and stable disease.

Methods

An economic decision model was developed using patient-level data for progression-free survival and overall survival from the SATURN (SequentiAl Tarceva in UnResectable NSCLC) study. An area under the curve model was developed; all patients entered the model in the progression-free survival health state and, after each month, moved to progression or death. A time horizon of 5 years was used. The model was conducted from the perspective of national health care payers in France, Germany, and Italy. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed.

Results

Treatment with erlotinib in first-line maintenance resulted in a mean life expectancy of 1.39 years in all countries, compared with a mean 1.11 years with best supportive care, which represents 0.28 life-years (3.4 life-months) gained with erlotinib versus best supportive care. In the base-case analysis, the cost per life-year gained was €39,783, €46,931, and €27,885 in France, Germany, and Italy, respectively.

Conclusion

Erlotinib is a cost-effective treatment option when used as first-line maintenance therapy for locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC.

Introduction

The prognosis for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) deteriorates with advancing disease stage, and only about 1% of patients with metastatic NSCLC are alive after 5 years.Citation1 The most appropriate treatment for these patients is palliative, systemic, platinum-based chemotherapy in first line.Citation2–Citation5 However, platinum-based, first-line treatment is limited to 4–6 cycles due to cumulative toxicity and a plateau in effectiveness. Following discontinuation of chemotherapy, most patients will experience disease progression within 2–3 months.Citation6,Citation7 Previous guidelines have recommended withholding second-line treatment until disease progression.Citation2,Citation3 However, Cappuzzo et al suggested that 30%–50% of patients were not receiving second-line treatment due to rapid disease progression and decreasing performance status.Citation8 Hence, there is a need for therapies that prolong the clinical benefits of first-line treatment.

Bevacizumab has been approved for use in patients with metastatic non-squamous NSCLC in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy until disease progression.Citation9 However, there remains an unmet need for further treatment options that extend survival in patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC.

An alternative treatment strategy that can be used to prolong duration of first-line treatment and extend survival in metastatic NSCLC is first-line maintenance therapy. Maintenance therapy is defined as the prolongation of treatment duration or administration of additional treatment at the end of a defined number of initial chemotherapy cycles, after maximum tumor response has been achieved (this may be complete response, partial response, or stable disease). Erlotinib (Tarceva®, F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland) is one of only two treatments approved for use as first-line maintenance therapy by the European Medicines Agency,Citation10 the other being pemetrexed.Citation11 The randomized, multicenter, Phase III SATURN (SequentiAl Tarceva in UnResectable NSCLC) study compared first-line maintenance therapy with either erlotinib or placebo (n = 487) following four cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with metastatic NSCLC.Citation8 Patients who had not experienced disease progression after initial chemotherapy were randomized 1:1 to receive erlotinib 150 mg/day orally + best supportive care or placebo + best supportive care until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or death.Citation8 Erlotinib therapy significantly improved progression-free survival (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.71; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.62–0.82; P < 0.0001) and overall survival (HR: 0.81, 95% CI: 0.70–0.95; P = 0.0088) in the intent-to-treat population (n = 438)Citation8 and in a subpopulation of patients (n = 252) with stable disease following initial first-line chemotherapy (progression-free survival HR: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.56–0.83; P < 0.0001; overall survival HR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.59–0.89; P = 0.0019Citation8). The survival benefits observed following erlotinib maintenance therapy in patients with mutated epidermal growth factor receptor and patients with wild-type epidermal growth factor receptor were also achieved without significantly compromising tolerability or health-related quality of life. The objective of this analysis was to estimate the cost-effectiveness of erlotinib versus best supportive care when used as first-line maintenance therapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC and stable disease following first-line therapy in three European countries, ie, France, Germany, and Italy.

Materials and methods

To estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness of erlotinib, an economic decision model was developed using patient data on progression-free survival and overall survival for erlotinib and best supportive care as first-line maintenance therapy from the SATURN trial.Citation8

Model structure

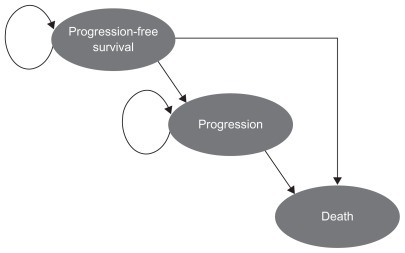

An area under the curve (or partitioned survival) model was developed consisting of three health states, ie, progression-free survival, progression, and death (). Survival data from the trial were used to follow patients from the progression-free survival to the progression and death states, and allowed for extrapolation of the data beyond the trial period. The model uses the stable disease population, as indicated in the European Union label,Citation12 to calculate efficacy and the same dose as was used in the trial, ie, erlotinib 150 mg/day orally + best supportive care or placebo + best supportive care. The area under the curve model works by assuming that, at any discrete time point, the difference between the proportion of patients in overall survival and the proportion of patients in progression-free survival determines the proportion of patients who have experienced disease progression. At the start of the analysis, it was assumed that all patients were in the progression-free survival health state. A half-cycle correction is used to account for events that occur during each monthly cycle. The time horizon of 5 years can be considered to be a lifetime perspective in this patient population (after 5 years, virtually all patients will have died).

The model was developed from the perspective of the national health care payer in three European countries, ie, France, Germany, and Italy; therefore, indirect costs, including travel costs, and costs to other public agencies were not included. Costs and health benefits were discounted by 3.5% for each country.

Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate the impact of changes in the key input parameters and assumptions on the results of the base-case analysis. Distributions around the following parameters were used to reflect uncertainty in the model (ie, the probability of erlotinib being cost-effective): estimates for the parametric progression-free survival and overall survival functions, and cost and frequency of adverse events. No distributions were applied for drug prices and administration costs.

Adverse events were selected for inclusion in the model by grade of severity and frequency of occurrence by event and treatment arm, according to the following rules: all treatment-related adverse events grade 3–4, and adverse events that occurred from the start of the study and 28 days after the last cycle of first-line treatment inclusively. The frequency of each event was further categorized into the number of patients experiencing at least one adverse event. The maximum number of adverse event episodes was also calculated. These values were used for calculating the average number of each adverse event per patient (eg, probability of a specified adverse event per patient × average number of episodes of adverse event per patient).

The model does not include post-progression-free survival treatments (following disease progression) once maintenance therapy is stopped, because it was not designed to incorporate this information. Therefore, second-line and further-line treatment costs, capturing the various treatment strategies used following progression, were not accounted for within the model. This was due to the variation in second-line treatment observed in the SATURN study; uncontrolled patients received multiple therapies after disease progression, which included taxanes (eg, docetaxel), antimetabolites (eg, pemetrexed), anti-neoplastic agents, epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (eg, erlotinib), and platinum compounds. In addition, insufficient data were reported in the SATURN study on second-line treatment dosing and duration.

Model inputs

Survival curves were fitted parametrically to the Kaplan–Meier progression-free survival and overall survival curves to facilitate extrapolation beyond the clinical trial period. Each parametric function was assessed for its goodness of fit to the data. The gamma functionCitation13,Citation14 provided the best fit for overall survival, whereas for progression-free survival the Gompertz distributionCitation14 was shown to be the best fit for the stable disease population. Therefore, these functions were used in all analyses to estimate and extrapolate progression-free survival and overall survival beyond the clinical trial period.

The cost of erlotinib was incorporated into the model using the country-specific list price of a pack of 30 × 150 mg tablets (€2130.00, €2928.24, and €1864.57 for France, Germany, and Italy, respectively) and was applied in the base-case analysis for the average treatment duration during the clinical trial (). As per the study protocol, patients received a single daily dose of erlotinib 150 mg orally. In order to calculate the monthly cost of erlotinib, the cost per 150 mg tablet (€71.00, €83.63, and €49.10, respectively) was multiplied by the average number of days per month (30.4 days, ). To estimate the resource use associated with administration of erlotinib, the appropriate reference costs associated with administration of oral medication in the pharmacy were used (). Administration costs were obtained from France,Citation15 Germany,Citation16 and Italy.Citation17 Country-specific estimates of the most likely minimum and maximum costs of treatment-related adverse events were employed to propagate the gamma distribution to express uncertainty in the cost of treating the event.Citation18 The cost values were then applied to the frequency of adverse events.Citation19–Citation21

Table 1 Treatment costs for erlotinib

Results

Comparison of the total average costs of alternative therapies for first-line maintenance shows that erlotinib was more costly than best supportive care in all three countries. Treatment with erlotinib in first-line maintenance resulted in a mean life expectancy of 1.39 years (16.7 months) in all countries, compared with a mean 1.11 years (13.3 months) with best supportive care, which represents 0.28 life-years (3.4 life-months) gained with erlotinib versus best supportive care.

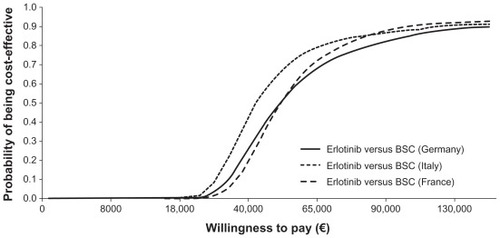

Results of the base-case and probabilistic analyses, presented as mean values and corresponding 95% CI for the latter are shown in . In the base-case analysis, the cost per life-year gained was €39,783, €46,931, and €27,885 in France, Germany, and Italy, respectively. In the probabilistic analysis, the cost per life-year gained was €39,214, €46,816, and €27,864, respectively. The variation in cost per life-year gained between countries was due to the difference in the total monthly cost of erlotinib, which comprises administration costs, acquisition costs, and costs of adverse events ().Citation22–Citation25 A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve for each country, generated from the probabilistic analysis, is presented in . These curves show that there is a 50% chance that erlotinib would be cost-effective in first-line maintenance with a willingness to pay approximately €50,000 in France and Germany and €40,000 in Italy.

Figure 2 Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for erlotinib versus best supportive care in first-line maintenance therapy.

Table 2 Cost-effectiveness of erlotinib versus placebo over patient lifetime: base-case and probabilistic analysis in patients with stable disease (3.5% discounted)

Table 3 Comparison of efficacy, costs, and cost-effectiveness of erlotinib and pemetrexed in three European markets

Discussion

Treatment of advanced or metastatic NSCLC is often considered costly; however, the value of a new treatment should incorporate the clinical benefit it provides compared with current treatment options, and the incremental cost of funding the new therapy versus the unmet need. In view of the current poor survival outcomes in metastatic NSCLC, it is of interest to consider the cost per life-year gained with a new therapy. An increase in health care expenditure in cancer care makes cost-effectiveness analysis an important tool for national health care payers.Citation26 This is the first analysis of its kind to present a cross-market analysis of cost per life-year gained for first-line maintenance therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC.

In each country, erlotinib resulted in a survival gain when compared with best supportive care. The difference between highest and lowest cost per life-year gained across the three countries was €19,000 for both base-case and probabilistic results. demonstrates that the chance of erlotinib being cost-effective versus best supportive care in first-line maintenance is relatively stable across the three countries, although slightly higher in Italy given the same willingness to pay.

A strength of the model is its transparency, given that the discrete health states closely match the end points measured in the clinical trial. The methods of extrapolation are also similar to those commonly suggested by the health economic community,Citation18 as well as the modeling methods widely reported in peer-reviewed publications.

Despite the strengths of the model, it is important to recognize any associated limitations. The model was developed to estimate the cost-effectiveness of treatment in the first-line maintenance setting only. Therefore, second-line treatment costs were not accounted for within the model. This was due to a variety of second-line and further-line treatments reported in the SATURN trial and insufficient data reported on treatment dosing and duration.

Pemetrexed, a multitargeted antifolate chemotherapeutic agent, is the only other therapy approved by the European Medicines Agency for use in first-line maintenance for metastatic NSCLC (in patients with non-squamous disease).Citation11 In the JMEN trial,Citation27 pemetrexed was associated with similar efficacy benefits versus best supportive care (progression-free survival HR: 0.50, 95% CI: 0.42–0.61; P < 0.0001)Citation27 as erlotinib versus best supportive care in the SATURN trial.

In a population-matched, indirect comparison analysis comparing erlotinib and pemetrexed as first-line maintenance therapy in metastatic NSCLC, both treatments were found to be similarly efficacious ().Citation23 An economic analysis of pemetrexed versus best supportive care in the US market showed that the cost per life-year gained using pemetrexed first-line maintenance therapy versus best supportive care in patients with advanced, non-squamous NSCLC was US$122,371 (€86,869).Citation22 The analysis suggests that pemetrexed is not cost-effective compared with best supportive care, given the cost-effectiveness ratios for medication typically reimbursed in the US, while our analysis shows that erlotinib is cost-effective when compared with best supportive care (). However, it is difficult to compare the cost-effectiveness of erlotinib and pemetrexed using the results of these three analyses. Pemetrexed was only efficacious in a non-squamous population and erlotinib was efficacious in both the intent-to-treat and stable disease populations. Patient distributions of key characteristics between the SATURN and JMEN studies were not balanced. The adenocarcinoma population varied by 3%, the number of patients with stage IIIb and IV disease varied by 8% between the two trials for both disease stages, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status varied by 9% for both 0 and 1. Patients in the JMEN trial had a better prognosis at baseline.Citation8,Citation27 Furthermore, drug costs in the US and Europe are different.

If a cost-effectiveness analysis of erlotinib versus pemetrexed were to be performed, the comparable efficacy of erlotinib and pemetrexed derived from the indirect comparison analysisCitation23 would make drug costs the key driver. Monthly costs of erlotinib and pemetrexed comprising administration, acquisition, and adverse event costs () derived from a manuscript in pressCitation28 (published in part at a recent scientific conferenceCitation24,Citation25) show erlotinib has lower monthly per-patient treatment costs. Based on these costs, a cost-effectiveness analysis of erlotinib versus pemetrexed might be expected to show that erlotinib is as efficacious as pemetrexed but less costly. However, the results would need to be interpreted with caution, given the imbalance in the key characteristics of patient populations between the SATURN and JMEN trials.Citation8,Citation27

Given that erlotinib is cost-effective versus best supportive care based on this economic analysis, and has efficacy similar to that of pemetrexed at a lower cost, it could become the new standard of care in first-line maintenance therapy in locally advanced and metastatic NSCLC. In addition to the clinical similarity and economic advantages of erlotinib over pemetrexed, erlotinib may also have other advantages due to a lower incidence of adverse events and an oral, as opposed to intravenous, formulation.Citation8 Oral treatment is often considered more convenient and is not usually associated with any administration costs. In contrast, intravenous administration can cost more than €500 in France and Germany.Citation16,Citation29

Conclusion

Erlotinib is a cost-effective treatment option versus best supportive care when used as first-line maintenance therapy for locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC in patients with stable disease. This study suggests that, in conjunction with toxicity and efficacy data, economic analyses are useful in defining the best maintenance strategy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Karen Hampshire, Robert Woods, and Gillian Sibbring at Complete Market Access for their assistance in the preparation and revision of the draft manuscript, based on detailed discussion and feedback from all the authors.

Disclosure

This study was funded by F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Funding for Complete Market Access and editorial assistance was also supported by F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. In the past 3 years, AV has received fees for lecturing and board membership from F Hoffmann-La Roche, Eli Lilly, and AstraZeneca. In the past 5 years, CC has received fees for attending scientific meetings, speaking, organizing research, or consulting from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, F Hoffmann-La Roche, Eli Lilly, and Amgen. HGB has received consulting and speaking fees from F Hoffmann-La Roche. DFH has received honoraria for lectures and advisory board participation from F Hoffmann-La Roche, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. FG has received honoraria for lectures and advisory board participation from F Hoffmann-La Roche, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, and Sanofi-Aventis. JAR is an employee of F Hoffmann-La Roche, the manufacturer of erlotinib, and SW was an employee during the submission of this manuscript.

References

- GroomePABolejackVCrowleyJJThe IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: validation of the proposals for revision of the T, N, and M descriptors and consequent stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumoursJ Thorac Oncol20072869470517762335

- PfisterDGJohnsonDHAzzoliCGAmerican Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003J Clin Oncol200422233035314691125

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in OncologyNon-small cell lung cancer v.2 Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/nscl.pdfAccessed May 18, 2011

- D’AddarioGFelipENon-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-upAnn Oncol200819Suppl 2ii39ii4018456762

- National Institute for Health and Clinical ExcellenceClinical Guideline 24. Lung cancerThe diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG024niceguideline.pdfAccessed May 18, 2011

- BrodowiczTKrzakowskiMZwitterMCisplatin and gemcitabine first-line chemotherapy followed by maintenance gemcitabine or best supportive care in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a phase III trialLung Cancer200652215516316569462

- FidiasPMDakhilSRLyssAPPhase III study of immediate compared with delayed docetaxel after front-line therapy with gemcitabine plus carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancerJ Clin Oncol200927459159819075278

- CappuzzoFCiuleanuTStelmakhLErlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 studyLancet Oncol201011652152920493771

- European Medicines AgencyAvastin summary of product characteristics Available from: http://www.emea.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000582/WC500029271.pdfAccessed December 15, 2010

- European Medicines AgencyCommittee for Medicinal Products for Human Use post-authorisation summary of positive opinion for Tarceva Available from: http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/opinion/51116606en.pdfAccessed May 18, 2011

- European Medicines AgencyCommittee for Medicinal Products for Human Use post-authorisation summary of positive opinion for Alimta Available from: http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/opinion/Alimta_9292908en.pdfAccessed May 18, 2011

- European Medicines Agency Committee for medicinal products for human use (CHMP)Summary of opinion (post authorisation)Tarceva (erlotinib) Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Summary_of_opinion/human/000618/WC500075850.pdfAccessed May 18, 2011

- WeissteinEWGamma functionFrom ‘MathWorld’ – A Wolfram Web Resource Available from: http://mathworld.wolfram.com/GammaFunction.htmlAccessed May 18, 2011

- CollettDModelling Survival Data in Medical Research2nd edBoca Raton, FLChapman & Hall2003

- Official Gazette GHS 9606. [Chemotherapy for tumors, in session] Available from: http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do;jsessionid=244B4669551731582BF775EC93B44BD2.tpdjo09v_2?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000021879531&dateTexte=&oldAction=rechJO&categorieLien=idAccessed January 20, 2011 French

- GatzemeierUPirkOGabrielAKotowaWHeigenerDSecond-line-therapy for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) – a retrospective cost analysisTumordiagn u Ther200829211217 German

- Conference of the Regions of Autonomous Provinces. Conventional single tariff for the provision of hospital care rules and rates applicable to the year 2009 Available from: http://www.regioni.it/upload/270110TUC_ASSISTENZA_OSPEDALIERA.pdfAccessed May 18, 2011 Italian

- BriggsASchulpherMClaxtonKDecision Modelling for Health Economic Evaluation1st edOxford, UKOxford University Press2006

- BischoffHGHeigenerDBanzKWalzerSCosts of treating severe adverse events observed with a regimen of bevacizumab plus chemotherapy versus cetuximab plus cisplatin/vinorelbine in the first-line therapy of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in Germany [abstract]Value Health2009127A265 Abstr PCN47

- ChouaidCVergnenegreABrunnerMWalzerSThe cost of treating grade 3/4 adverse events related to first-line therapy with bevacizumab plus chemotherapy versus cetuximab plus cisplatin/vinorelbine for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in France [abstract]Value Health2009127A264 Abstr PCN43

- HeigenerDBischoffHGBanzKWalzerSCost savings related to superior adverse event profile of bevacizumab plus chemotherapy versus cetuximab plus cisplatin/vinorelbine in the first-line therapy of advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in Germany: a sensitivity analysis on the EGOG status [abstract]Value Health2009127A265 Abstr PCN46

- KleinRWielageRMuehlenbeinCCost-effectiveness of pemetrexed as first-line maintenance therapy for advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancerJ Thorac Oncol2010581263127220581708

- CascianoRBischoffHNuijtenMMalangoneERayJMaintenance erlotinib versus pemetrexed for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: indirect comparison applying real-life outcomes [abstract]Value Health2010137A254 Abstr PCN20

- RaveraSWalzerSRayJCost comparison of erlotinib versus pemetrexed for the first-line maintenance treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer in Italy [abstract]Value Health2010137A259 Abstr PCN43

- Castro de CarpenoJCastro-GómezAJWalzerSRayJCost comparison of erlotinib versus pemetrexed for the first-line maintenance treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer in Spain [abstract]Value Health2010137A259 Abstr PCN44

- LearnPABachPBPem and the cost of multicycle maintenanceJ Thorac Oncol2010581111111220661082

- CiuleanuTBrodowiczTZielinskiCMaintenance pemetrexed plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care for non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 studyLancet200937496991432144019767093

- NuijtenMJde Castro CarpenoJChouaidCA cross-market cost comparison of erlotinib versus pemetrexed for first-line maintenance treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancerLung Cancer2011In press

- Department of Health and SportsOrder of 27/02/2010 fixing for 2010 the tariff rules referred to in I and IV of Article L. 162-22-10 of the Code of Social Security and IV and V of the amended article 33 of the finance act 2004 for social securityOfficial Gazette No 502010 French