Abstract

Background

Prevention strategies for pressure ulcer formation remain critical in patients with an advanced illness. We analyzed factors associated with the development of pressure ulcers in patients hospitalized in a palliative care ward setting.

Patients and methods

This study was a retrospective analysis of 329 consecutive patients with a mean age (± standard deviation) of 70.4±11.8 years (range: 30–96 years, median 70.0 years; 55.3% women), who were admitted to the Palliative Care Department between July 2012 and May 2014.

Results

Patients were hospitalized for mean of 24.8±31.4 days (1–310 days, median 14 days). A total of 256 patients (77.8%) died in the ward and 73 patients (22.2%) were discharged. Two hundred and six patients (62.6%) did not develop pressure ulcers during their stay in the ward, 84 patients (25.5%) were admitted with pressure ulcers, and 39 patients (11.9%) developed pressure ulcers in the ward. Four factors assessed at admission appear to predict the development of pressure ulcers in the multivariate logistic regression model: Waterlow score (odds ratio [OR] =1.140, 95% confidence interval [CI] =1.057–1.229, P=0.001), transfer from other hospital wards (OR =2.938, 95% CI =1.339–6.448, P=0.007), hemoglobin level (OR =0.814, 95% CI =0.693–0.956, P=0.012), and systolic blood pressure (OR =0.976, 95% CI =0.955–0.997, P=0.023). Five other factors assessed during hospitalization appear to be associated with pressure ulcer development: mean evening body temperature (OR =3.830, 95% CI =1.729–8.486, P=0.001), mean Waterlow score (OR =1.194, 95% CI =1.092–1.306, P<0.001), the lowest recorded sodium concentration (OR =0.880, 95% CI =0.814–0.951, P=0.001), mean systolic blood pressure (OR =0.956, 95% CI =0.929–0.984, P=0.003), and the lowest recorded hemoglobin level (OR =0.803, 95% CI =0.672–0.960, P=0.016).

Conclusion

Hyponatremia and low blood pressure may contribute to the formation of pressure ulcers in patients with an advanced illness.

Introduction

Pressure ulcers represent a frequent and significant challenge for medical, nursing, and social care systems among the elderly, disabled, and other patient populations.Citation1–Citation6 Deterioration of physical, psychological, and social health due to pressure ulcers within susceptible patients is often devastatingCitation7,Citation8 and increases the risk of death.Citation9 While prolonged skin pressure, shear stress, and/or friction are primary causal factors leading to ulcer formation, variability of pressure ulcer risk factors, prevalence, incidence, and prognosis have been observed in different patient populations.Citation1–Citation3 Advanced chronic illness, defined as patients receiving supportive and palliative care,Citation10 combined with nutritional deterioration, weakness, immobility, and skin alterations, is particularly associated with the risk of pressure ulcer development.Citation1,Citation3,Citation10 Excessive skin moisture, urine or fecal incontinence, and urinary catheterization are other factors that have previously been shown to increase pressure ulcer incidence in terminally ill patients.Citation3 Major surgery may contribute to increased formation of pressure ulcers in patients with colorectal cancer.Citation11 Advanced age, alterations to sensory perception, body temperature alterations, as well as poor general and mental health are conditions that can augment the individual risk for pressure ulcer development.Citation3 Pressure ulcerations may result from impaired tissue perfusion and oxygenation as sequelae of general health-related conditionsCitation12 or local factors (peripheral vascular disease, diminished skin vascular density).Citation13 Ischemia-reperfusion injury is an additional major component that participates in cutaneous necrosis.Citation14 Wound formation is followed by inflammation that may cause further perfusion deteriorationCitation15 and impair wound healing if uncontrolled.Citation16 Infection is a common, potentially serious pressure ulcer complication with local and systemic effects.Citation17 Nearly all individuals in palliative care are susceptible to pressure ulcer development; thus, risk assessment and prevention strategies are strongly recommended.Citation3 Pressure ulcer prevention is an essential component of palliative care for maintaining patient quality of life.Citation1 Prevention of pressure ulcer formation has been shown to be a cost-effective endeavor.Citation18,Citation19 Studies have shown that treatment costs of severe pressure ulcers are significantly higher than prevention strategy implementation.Citation2,Citation20 In addition, the lack of effective pressure ulcer formation prevention strategies may expose providers to financial liability.Citation21 While there is an increased understanding of the conditions associated with pressure sore development among palliative care patients, the need for further investigations on this important topic has been raised.Citation10 Many of the prevention strategies that have been previously described focus on outpatient and acute hospital settings. However, inpatient pressure ulcer prevention strategies remain critical for respite care among palliative patients.Citation1 Our objective was to analyze factors associated with the development of pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients with advanced illness.

Patients and methods

Study design

This study was a retrospective analysis of factors that influence pressure ulcers in patients with an advanced illness based on medical records of the Palliative Care Unit of Independent Public Healthcare Railway Hospital in Wilkowice-Bystra, Poland.

Patients

The analysis included 329 consecutive patients admitted to the Palliative Care Department between July 2012 and May 2014, with a mean age (± standard deviation) of 70.4±11.8 years (range: 30–96 years, median 70.0). Of the patients admitted, 55.3% were women and 44.7% were men.

Procedures

Patient diagnosis, treatment, and care were in accordance with hospice care standards of the Ministry of Health and the National Health Fund of Poland. Prevention strategies were applied uniformly and consistently to all patients (). As part of standard operating procedures, patient admissions were subject to standardized history taking, physical examination, functional assessment, and laboratory tests. In addition, assessment of nutritional status and acute and chronic pain with emphasis on cancer pain was applied. Functional assessment included the Barthel index.Citation22 Blood tests included complete blood count, electrolytes, uric acid concentration, and arterial blood gas analysis. The patients were evaluated daily, and blood tests were repeated according to clinical indications. Sodium and potassium were assessed several times during hospitalization. Within 2 hours of admission, the risk of decubitus pressure ulcer formation was assessed using the Waterlow scale,Citation23 assessed daily and the mean calculated. Waterlow scale is scored from 0 to 64. Waterlow scores ≥10 indicate increased risk of pressure ulcer development, ≥15 a high risk, and ≥20 a very high risk.

Table 1 Pressure ulcer prevention strategies applied in the Palliative Care Unit at Independent Public Healthcare Railway Hospital in Wilkowice–Bystra, Poland

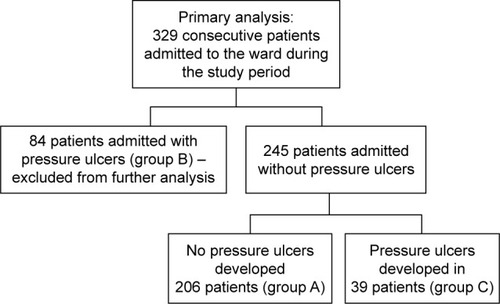

Patients were classified according to decubitus pressure ulcer development: group A included patients who avoided pressure ulcer development, group B included patients admitted to the ward with pressure ulcers, and group C included patients who developed pressure ulcers in the ward.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistica version 10 (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Chi-square test, V-square test, and Fisher’s exact test were used for categorical variables and nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was used for quantitative variables to compare patients who developed decubitus pressure ulcers during hospitalization with those who did not. Multivariate binary logistic regression was performed to assess measures associated with decubitus pressure ulcer development: separately for parameters assessed at admission and for mean values of parameters measured serially during hospitalization. The variables were adjusted for clinical, functional, and laboratory factors. Multivariate analysis with backward elimination included variables that yielded P-values of 0.1 or lower in the initial univariate analysis. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate probability of pressure ulcer-free hospitalization in subgroups of patients in respect to selected variables, while differences between these subgroups were assessed with the Gehan’s Generalized Wilcoxon statistic. Variables were tested to define the value corresponding with the lowest P-level. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics

The study protocol was registered with and approved by the Bioethical Committee of the Regional Medical Chamber in Bielsko–Biala (Komisja Bioetyczna Beskidzkiej Izby Lekarskiej w Bielsku-Bialej, Letter No 2014/07/17/7 July 17th 2014). Since our study is a retrospective analysis, patient consent for medical record review was not required by the Bioethical Committee.

Results

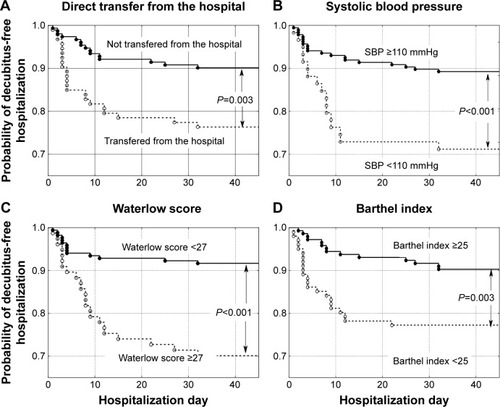

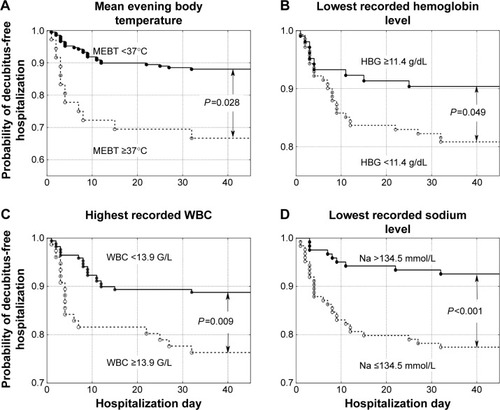

Patients were hospitalized for a mean of 24.8±31.4 days, ranging from 1–310 days (median 14 days). A total of 256 patients (77.8%) died in the ward, while 73 (22.2%) were discharged. In total, 313 patients (95.1%) suffered from cancer: lung cancer (21.3%), colorectal cancer (11.6%), breast cancer (6.1%), brain cancer (5.8%), stomach cancer (5.8%), and other cancer (44.5%). Sixteen patients (4.9%) were admitted because of non-oncological diseases, mostly (13 patients, 4.0%) because of severe chronic heart failure. Two hundred and six patients (62.6%) did not develop pressure ulcers during their stay in the ward (group A), 84 patients (25.5%) were admitted to the ward with pressure ulcers (group B), and 39 patients (11.9%,) developed pressure ulcers while in the ward (group C). Group C and group A (as a control) were included in further analysis (). Compared to patients who did not develop pressure ulcers during hospitalization (group A), patients who developed pressure ulcers (group C) presented more frequently with colorectal cancer, higher body mass reduction within 6 months, a longer period of physical deterioration, longer pre-admission nursing home residency, lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure, lower hemoglobin level, and higher white blood cell count at admission, as well as lower Barthel index and Waterlow scores at admission (). Patients directly transferred from other hospital wards presented with lower Barthel index scores (29.8±24.8 vs 40.0±25.6 points, P=0.001). Individuals who were not transferred directly from other hospital wards had higher probability of decubitus pressure ulcer-free hospitalization (P=0.003) as did those with systolic blood pressure ≥110 mmHg (P<0.001), Waterlow scores <27 points (P<0.001), and Barthel index scores ≥25 points (P=0.003) (), as well as those with a mean evening body temperature <37°C, lowest recorded hemoglobin level ≥11.4 g/dL, highest recorded white blood cells <13.9 G/L, and lowest recorded sodium level >134.5 mmol/L (). Four factors assessed at admission appear predictive for pressure ulcer development in a multivariate logistic regression model: Waterlow score (odds ratio [OR] =1.140, 95% CI =1.057–1.229, P=0.001), patients admitted from other hospital wards (OR =2.938, 95% CI =1.339–6.448, P=0.007), hemoglobin level (OR =0.814, 95% CI =0.693–0.956, P=0.012), and systolic blood pressure (OR =0.976, 95% CI =0.955–0.997, P=0.023). Five factors assessed during hospitalization appear to be associated with decubitus pressure ulcer development: mean evening body temperature (OR =3.830, 95% CI =1.729–8.486, P=0.001), mean Waterlow score (OR =1.194, 95% CI =1.092–1.306, P<0.001), the lowest recorded sodium concentration (OR =0.880, 95% CI =0.814–0.951, P=0.001), mean systolic blood pressure (OR =0.956, 95% CI =0.929–0.984, P=0.003), and the lowest recorded hemoglobin level (OR =0.803, 95% CI =0.672–0.960, P=0.016).

Table 2 Comparison of demographic, clinical, and functional characteristics of hospice patients who developed (group C) and did not develop (group A) pressure ulcers while hospitalized

Figure 2 Probability of decubitus-free hospitalization in palliative care ward patients according to (A) transfer from home or nursing care settings versus direct transfer from other hospital wards, (B) systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥110 mmHg versus lower values, (C) Waterlow scores <27 points versus higher values, and (D) Barthel Index of Activities of Daily Living (Barthel index) ≥25 points versus lower values.

Figure 3 Probability of decubitus-free hospitalization in palliative care ward patients according to (A) mean evening body temperature (MEBT) <37°C versus higher values, (B) lowest recorded hemoglobin level (HBG) ≥11.4 g/dL versus lower values, (C) highest recorded white blood cells (WBC) <13.9 G/L versus higher values, and (D) lowest recorded sodium level >134.5 mmol/L versus lower values.

Discussion

Our study analyzed the risk factors of pressure ulcer formation in a heterogeneous group of patients with an advanced illness, with a mean age of 70.4 years and a median age of 70.0 years, hospitalized at a palliative care unit. Most patients passed away in the unit and only a fifth of the patients were discharged. A majority of the patients suffered from advanced cancer and a minority from other advanced illnesses, mainly chronic heart failure. These conditions are associated with a risk of pressure ulcer formation.Citation10 The Waterlow scaleCitation23 was used to assess the risk of pressure ulcer development. Although its predictive value was found to be limited,Citation24,Citation25 it is still recommended for pressure ulcer risk assessment.Citation26 We observed greater pressure ulcer incidence with colorectal cancer, accelerated body mass reduction during the last 6 months, longer periods of physical deterioration, and longer pre-admission nursing home residency. Further multivariate logistic regression analysis identified four independent factors predictive of pressure ulcer formation at admission: direct transfer from hospital ward, high Waterlow score, low hemoglobin level, and low systolic blood pressure at admission. Pressure ulcer development and the association with direct transfer from other hospital wards may be due to the poorer general health status of such patients, who were most likely referred to the Palliative Care Department because of an advanced illness. Low hemoglobin levels may be both a symptom of more advanced disease and a cause of diminished tissue oxygenation. Similarly, blood pressure tends to decrease with chronic disease progression,Citation16 and hypotension may be associated with decreased peripheral tissue perfusion. It is worth noting that hypertensive patients suffering from comorbid chronic diseases are often treated with antihypertensive agents despite very low blood pressure in the context of advanced chronic diseases. Multivariate logistic regression analysis also allowed identification of five other factors assessed during hospitalization and associated with the pressure ulcer formation. We observed that elevated mean evening temperature was a measure associated with pressure ulcer formation. Hyponatremia was not previously considered a factor associated with pressure ulcer formation in patients with advanced diseases. However, there is increasing evidence that the lowest recorded serum sodium level, or hyponatremia, is associated with poorer prognosis in different groups of patients irrespective of underlying disease. Decreased sodium levels, within the normal sodium range, were associated with increased major cardiovascular events and mortality in elderly men without previously diagnosed cardiovascular disease.Citation27 Hyponatremia in patients after acute myocardial infarction was shown to be an independent predictive factor for increased long-term mortality.Citation28 Among internal medicine department inpatients, hyponatremia was associated with increased 30-day and 1-year mortality, regardless of underlying disease. In addition, a decrease of serum sodium from 139 to 132 mmol/L was shown to correlate with an increased risk of death.Citation29 Hyponatremia was also found to increase the risk of fallsCitation30 and fractures.Citation8 Our observations suggest that decreased serum sodium is a factor in increased pressure ulcer development risk. It could be assumed that hyponatremia is an index of progressive deterioration in patients with advanced illnesses, which also lowers blood pressure, skin turgor, and peripheral tissue perfusion. This finding needs further study as it may have important implications for the care of patients with advanced illness.

Hyponatremia in terminal patients has been associated with a wide range of detrimental symptoms and signs.Citation31 Establishing the etiology of hyponatremia is essential for treatment. Serum sodium levels are dependent on fluid balance. Low serum sodium levels may be caused by inadequately low sodium intake (dietary restrictions, low sodium content in intravenous fluids), excessive sodium wasting (vomitus, diarrhea, cerebral salt-wasting syndrome [CSWS]), and excessive water retention (syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone [SIADH], heart, or renal failure).Citation32,Citation33 Both diagnosis and treatment of disorders responsible for hyponatremia may be difficult in a palliative patient. A majority of palliative patients suffer from cancer with comorbid conditions. Consequently, hyponatremia in terminal patients is frequently of complex multi-factorial and multi-etiological origin.Citation34,Citation35 If hypothyroidism or adrenal insufficiency is diagnosed, hormone replacement therapy is indicated. Cancer (especially of the lung, breast, head, and neck) is frequently associated with SIADH or (less frequently) CSWS. Hyponatremia secondary to congestive heart failure, renal insufficiency, or liver cirrhosis may be resistant to treatment.Citation32 Importantly, a review of pharmacological agents, in terms of potential adverse drug reactions, is warranted. Modification of medications should be implemented where appropriate and feasible. Hyponatremia and low blood pressure may be induced by multiple drugs used frequently in palliative patients, including diuretics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, opioids, antiepileptic drugs, neuroleptics, and sulfonylurea derivatives.Citation36 Clinicians must practice vigilance when determining appropriate pharmacological and fluid therapy for terminal patients with multiple conditions in order to avoid the development of hyponatremia. As such, introduction of early medication and dietary (sodium intake) review should be initiated for terminal patients. Such consideration may prove helpful in avoiding serious complications caused by hyponatremia in palliative care patients.

The retrospective nature of this study limited the range of collected data and lacked predefined regular procedures in patient monitoring. In addition, bacteriological cultures were not taken in the patient population studied. Despite these limitations, it seems that our study added new information of potential significance for the prevention of pressure ulcer development in hospitalized patients with advanced illness.

Conclusion

Hyponatremia and low blood pressure may contribute to pressure ulcer formation in patients with advanced illness.

Author contributions

Danuta Sternal was involved in study conception and design; evaluation of the subjects; data collection, analysis, and interpretation; drafting the article, and revising drafts. Jan Szewieczek was responsible for study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, and revising drafts. Krzysztof Wilczyński was involved in analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, and revising drafts. All the authors approved the final paper.

Acknowledgments

The funding for the study was supported by University of Bielsko-Biala, Poland. However, the funding body played no role in the formulation of the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of this paper.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- ChaplinJPressure sore risk assessment in palliative careJ Tissue Viability200010273110839093

- DemarréLVan LanckerAVan HeckeAThe cost of prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: a systematic reviewInt J Nurs Stud2015521754177426231383

- LangemoDHaeslerENaylorWTippettAYoungTEvidence-based guidelines for pressure ulcer management at the end of lifeInt J Palliat Nurs20152122523226107544

- GarberSLRintalaDHPressure ulcers in veterans with spinal cord injury: a retrospective studyJ Rehabil Res Dev20034043344115080228

- PetzoldTEberlein-GonskaMSchmittJWhich factors predict incident pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients? A prospective cohort studyBr J Dermatol20141701285129024641731

- CoomerNMKandilovAMImpact of hospital-acquired conditions on financial liabilities for Medicare patientsAm J Infect Control2016441326133427174461

- QaseemAHumphreyLLForcieaMAStarkeyMDenbergTDClinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of PhysiciansTreatment of pressure ulcers: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of PhysiciansAnn Intern Med201516237037925732279

- ChrismanCACare of chronic wounds in palliative care and end-of-life patientsInt Wound J2010721423520528993

- KhorHMTanJSaedonNIDeterminants of mortality among older adults with pressure ulcersArch Gerontol Geriatr20145953654125091603

- White-ChuEFReddyMPressure ulcer prevention in patients with advanced illnessCurr Opin Support Palliat Care2013711111523328734

- Hernandez-BoussardTMMcDonaldKMMorrisonDERhoadsKFRisks of adverse events in colorectal patients: population-based studyJ Surg Res201620232833427229107

- SchubertVHypotension as a risk factor for the development of pressure sores in elderly subjectsAge Ageing1991202552611927731

- GreenwoodCMcGinnisEA retrospective analysis of the findings of pressure ulcer investigations in an acute trust in the UKJ Tissue Viability201625919726972582

- TongMTukBHekkingIMHeparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan mimetic improves pressure ulcer healing in a rat model of cutaneous ischemia-reperfusion injuryWound Repair Regen20111950551421649786

- CushingCAPhillipsLGEvidence-based medicine: pressure soresPlast Reconstr Surg20131321720173224281597

- JiangLDaiYCuiFExpression of cytokines, growth factors and apoptosis-related signal molecules in chronic pressure ulcer wounds healingSpinal Cord20145214515124296807

- HornSDBarrettRSFifeCEThomsonBA predictive model for pressure ulcer outcome: the Wound Healing IndexAdv Skin Wound Care20152856057226562203

- PadulaWVMishraMKMakicMBSullivanPWImproving the quality of pressure ulcer care with prevention: a cost-effectiveness analysisMed Care20114938539221368685

- PhamBTeagueLMahoneyJEarly prevention of pressure ulcers among elderly patients admitted through emergency departments: a cost-effectiveness analysisAnn Emerg Med201158468478.e321820208

- DealeyCPosnettJWalkerAThe cost of pressure ulcers in the United KingdomJ Wound Care20122126126226426622886290

- BennettRGO’SullivanJDeVitoEMRemsburgRThe increasing medical malpractice risk related to pressure ulcers in the United StatesJ Am Geriatr Soc200048738110642026

- MahoneyFIBarthelDWFunctional evaluation: the Barthel IndexMd State Med J1965146165

- WaterlowJPressure sores: a risk assessment cardNurs Times1985814955

- SchoonhovenLHaalboomJRBousemaMTThe prevention and pressure ulcer risk score evaluation study. Prospective cohort study of routine use of risk assessment scales for prediction of pressure ulcersBMJ200232579712376437

- AnthonyDParboteeahSSalehMPapanikolaouPNorton, Waterlow and Braden scores: a review of the literature and a comparison between the scores and clinical judgementJ Clin Nurs20081764665318279297

- National Institute for Health and Care ExcellencePressure ulcers: prevention and management. Clinical guideline [CG179] Published: April 23, 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg179Accessed June 28, 2016

- WannametheeSGShaperAGLennonLPapacostaOWhincupPMild hyponatremia, hypernatremia and incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in older men: a population-based cohort studyNutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis201626121926298426

- BurkhardtKKirchbergerIHeierMHyponatraemia on admission to hospital is associated with increased long-term risk of mortality in survivors of myocardial infarctionEur J Prev Cardiol2015221419142625389071

- Holland-BillLChristiansenCFHeide-JørgensenUHyponatremia and mortality risk: a Danish cohort study of 279 508 acutely hospitalized patientsEur J Endocrinol2015173718126036812

- TachiTYokoiTGotoCHyponatremia and hypokalemia as risk factors for fallsEur J Clin Nutr20156920521025226820

- Drake-HollandAJNobleMIThe hyponatremia epidemic: a frontier too far?Front Cardiovasc Med201633527774451

- McGrealKBudhirajaPJainNYuASCurrent challenges in the evaluation and management of hyponatremiaKidney Dis (Basel)20162566327536693

- WeismannDSchneiderAHöybyeCClinical aspects of symptomatic hyponatremiaEndocr Connect Epub201698

- YoonJAhnSHLeeYJKimCMHyponatremia as an independent prognostic factor in patients with terminal cancerSupport Care Cancer2015231735174025433438

- NairSMaryTRTareySDDanielSPAustineJPrevalence of hyponatremia in palliative care patientsIndian J Palliat Care201622333726962278

- LiamisGMilionisHElisafMA review of drug-induced hyponatremiaAm J Kidney Dis20085214415318468754