Abstract

Caring for a relative with dementia is extremely challenging; conventional interventions may not be highly effective or easily available on some occasions. This study aimed to explore the efficacy of mindfulness training in improving stress-related outcomes in family caregivers of people with dementia using a meta-analytic review. We searched randomized controlled trials (RCT) through April 2017 from five electronic databases, and assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration tool. Seven RCTs were included in our review. Mindfulness interventions showed significant effects of improvement in depression (standardized mean difference: −0.58, [95% CI: −0.79 to −0.37]), perceived stress (−0.33, [−0.57 to −0.10]), and mental health-related quality of life (0.38 [0.14 to 0.63]) at 8 weeks post-treatment. Pooled evidence did not show a significant advantage of mindfulness training compared with control conditions in the alleviation of caregiver burden or anxiety. Future large-scale and rigorously designed trials are needed to confirm our findings. Clinicians may consider the mindfulness program as a promising alternative to conventional interventions.

Introduction

Dementia has become a serious public health concern due to rapid population ageing. The progressively irreversible disease affects approximately 47 million people worldwide, and the number rises increasingly.Citation1 People with dementia are affected by cognition deficits, emotional disorders, and even behavior disturbances, all of which eventually lead to inability to function independently.Citation2 The burden of intensively caring for these dependent patients is consequently put on family caregivers in most cases, and the duration of in-home caregiving can be as long as a median of 6.5 years.Citation3 High levels of stress are reported in virtually all dementia caregivers, predisposing this vulnerable population to develop psychological and physical morbidity,Citation4 and even resulting in early mortality.Citation5 The burden of caregiving can not only greatly impair the well-being and quality of life of dementia caregivers, but also be associated with a high possibility of patient institutionalization. Because of all of that, any intervention that can support caregivers to reduce their stress should be greatly welcome.

Numerous psychosocial interventions have been developed for dementia caregivers, including information provision, social support or skills training such as behavior modification techniques, etc. However, most of these achieved only mild-to-modest efficacy in reducing caregiver distress.Citation6–Citation8 Although some treatments enjoyed stronger empirical support, such as those relying on the cognitive behavioral therapy framework (not including mindfulness-based cognitive therapy)Citation9 and the recent ambitious interventions such as Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregivers Health,Citation10,Citation11 these programs are heavily dependent on humans (ie, clinical psychologists) and/or economic resources. Thus, access to these potentially effective programs can be limited because of economic, geographic, and policy barriers.

Therefore, there may not be a “one-size-fits-all” intervention that is both highly effective and easily available to various kinds of dementia caregivers. Furthermore, no matter how skillful or competent caregivers are, which is among the main goals of many conventional interventions, caregivers are bound to feel burdensome and overwhelmed from time to time. This is where the wisdom of mindfulness through strengthening inner resources likely comes in.

Borrowing wisdom from Buddhist meditation, mindfulness has aroused great interest recently in scientific literature. Mindfulness is often operationally defined as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience”.Citation12 Mindfulness can be translated in various ways in the interventions such as the mindfulness-based stress reduction, yogic meditation, and those incorporated into behavioral therapies (eg, acceptance and commitment therapies). Mounting evidence shows that mindfulness-based programs are associated with reducing multiple negative dimensions of psychological outcomes such as perceived stress, depressive symptoms and anxiety, as well as enhancing the quality of life both acutely and chronically in a range of populations.Citation13–Citation15 Particularly, the individuals benefiting from mindfulness were mostly facing considerable stress in their lives; these individuals included organ transplant recipients,Citation16 patients with cancer,Citation17,Citation18 HIV,Citation19 or psychological disorders.Citation20,Citation21 Given the potentially positive effects of mindfulness for enhancing the ability to cope with distress, it makes sense that mindfulness would also benefit dementia caregivers who are especially likely to report similar problems that mindfulness has been shown to alleviate.

Previous reviews did provide preliminary evidence of the mental benefits of mindfulness for caregivers.Citation22–Citation25 However, these reviews have largely included uncontrolled trials (the pre–post study without a comparison group), the results from which cannot eliminate the risk of self-selection bias. For instance, people who believe in the benefits of mindfulness are more likely to enroll in a mindfulness program and report that they benefited from one. Additionally, sample sizes of caregiver trials have been relatively small, especially in the new area of investigation such as mindfulness interventions. In this context, the value of a meta-analysis, based on aggregation of individual studies, is to increase the power of detecting the real effect as statistically significant, if it exists. Yet, most previous reviews have synthesized the results narratively without using meta-analytic techniques.Citation22,Citation24,Citation25 Although one previous review assessed the effectiveness of mindfulness training by using a meta-analytic technique, this study did not exclusively focus on caregivers of persons with dementia.Citation23

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we aimed to determine the efficacy of mindfulness training relative to control conditions in improving stress-related outcomes (depression, anxiety, perceived stress, burden, and mental health-related quality of life) in family caregivers of people with dementia.

Methods

Search strategy

We searched the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, and CINAHL. We searched these databases up until April 2017. The search terms we used pertained to mindfulness (“mindful*” or “MBCT” or “MBSR” or “mindfulness-based cognitive therapy” or “mindfulness-based stress reduction”) AND dementia (“dementia*” or “Alzheimer*”) AND caregivers (“caregiv*” or “care-giv*” or “carer*”). Search details are shown in the Supplementary materials, –. In addition, we searched the reference lists of previous relevant reviews.Citation22–Citation25

Eligibility criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) which compared mindfulness-based interventions with controls in family caregivers of relatives with any type of dementia living in the community setting. Studies focusing on care workers (ie, nurses) rather than family caregivers were not included. We defined mindfulness-based interventions broadly to include mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and those combining the component of mindfulness with behavioral therapies (ie, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy) or meditation-based interventions. For the comparison groups, we considered active controls, usual care or wait-list controls. In this review, the primary outcome was caregivers’ levels of depression; the secondary outcomes included caregivers’ levels of anxiety, perceived stress, caregiver burden, and mental health-related quality of life. The included studies had to measure at least one of these outcomes with psychometrically valid and reliable tools which can be used to calculate effect sizes. Additionally, included studies were written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Data management

Two reviewers (ZL and QLC) independently screened the articles in two stages: at the title and abstract level and then at the full-text level. We extracted data regarding the eligibility criteria (RCT or not, targeted population, targeted outcomes); characteristics of caregivers and persons with dementia (age, gender, relationship between caregivers and persons with dementia, etc.); characteristics of interventions (sessions, duration, frequency); types of control groups and outcomes. Any disagreements were discussed between the two reviewers or solved by consulting a third reviewer (YYS) until consensus was reached.

Assessment of risk of bias

We assessed the risk of bias of individual studies using the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias tool.Citation26 We judged whether each study was at a low, high or unclear risk of bias for domains in selection bias, detection bias, and attrition bias. Regarding selection bias, we assessed the sequence of generation and allocation concealment. As a result of the expected small sample sizes of included trials, we also evaluated the comparability of baseline characteristics between the intervention and control groups. Concerning detection bias, we judged whether outcome assessors for our primary outcome (depression) were blinded to allocation. For attrition bias, we appraised not only the comparability of caregiver characteristics between the completers and the drop-outs, but also if the study adopted intention-to-treat analysis. In fact, it is nearly impossible to blind patients and delivery individuals in psychosocial interventions, so we did not include the assessment of performance bias or blinding of personnel and participants. Two reviewers (ZL and QLC) independently assessed the risk of bias and resolved disagreements by discussion or consultation with a third reviewer (YYS).

Statistical analyses

We entered the available data directly into RevMan version 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) for Mac computers. As our focused outcomes were continuous data, we calculated the standardized mean differences (SMD; effect size [ES]; Cohen’s d) which were determined by mean differences of the main treatment effect between the mindfulness training group and the control group divided by the pooled standard deviation. We used immediate post-intervention values to calculate the main treatment effect. If more than one outcome measure was reported on a certain domain, we chose scales that were common to the other trials to make comparisons more meaningful. We then combined SMD using inverse variance methods and applied a random effects model for the meta-analysis as we expected a considerable amount of heterogeneity across included studies.

The statistical heterogeneity was assessed by visual inspection of forest plots, tests of significance (p-value), and the I2 statistic. The level of heterogeneity across studies was rated as low, moderate or high corresponding to I2 value of 25%, 50%, or 75%. If moderate or high levels of heterogeneity were identified across sufficient studies which were included, we would consider conducting subgroup or meta-regression analyses based on the potential effect modifiers.

Results

Study selection

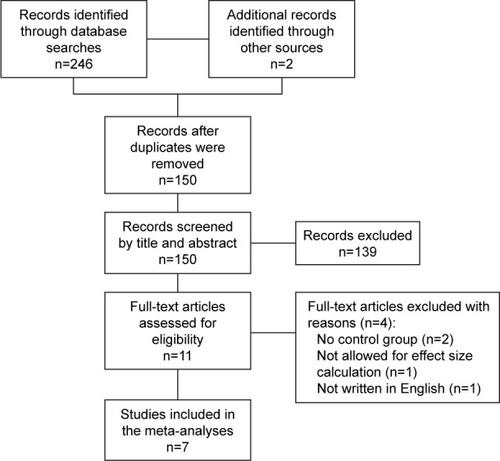

A total of 248 studies were identified from searching the databases and reference lists of included studies and previous systematic reviews.Citation22–Citation25 After screening the titles and abstracts, eleven full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, seven studies met our inclusion criteria. A flow diagram of the selection of studies is shown in .

Description of studies

The major characteristics of seven included studies published between 2010 to 2017 are presented in . Five included trials were conducted in the USA;Citation27–Citation31 the others were conducted in SpainCitation32 or Hong Kong.Citation33 The sample size of individual studies ranged from 19 to 141. The mean age of caregivers varied from 57 to 63 years. Women constituted the majority of caregivers (more than 80%) in all included studies. Spousal caregivers accounted for 26% to 74% of the entire sample. All included trials reported caregivers’ levels of depression, four trials assessed perceived stress and mental health-related quality of life among caregivers, and only three trials measured caregivers’ level of anxiety and burden associated with caregiving.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

Four trials employed a structured MBSR including six to eight weekly sessions lasting from 1.5 to 2.5 hours;Citation27,Citation29,Citation31,Citation33 others used mindfulness programs focusing on acceptance and commitment therapy,Citation32 yogic meditation,Citation28 or a combination of mindfulness with mantra meditation.Citation30 Adherence to mindfulness training was generally good; the drop-out rate for most trials was less than 20%.Citation25–Citation27,Citation29–Citation31 Four included studies used active controls, including education or social support,Citation27,Citation29,Citation31 or listening to relaxation music.Citation28 Other studies included control groups in which participants had decreased contact or social support from the interventionists compared with the participants in the intervention groups.Citation30,Citation32,Citation33

Assessment of the risk of bias

summarizes the risk of bias ratings of our included studies. Although all trials were described as “randomized”, the randomization technique was unclear in two studies.Citation27,Citation30 All trials assessed the success of randomization by comparing the baseline variables of the comparisons, and four of them were rated as having a high risk of bias because of significant differences between the intervention and comparison groups which may have influenced intervention effects.Citation27,Citation30–Citation32 For allocation concealment, we could only find clear information in two included trials.Citation28,Citation33 Because our primary outcome (depression) was always measured by self-rated tools, the blinding of outcome assessors was assessed as having a high risk of bias for all included trials. Among the four trials comparing the characteristics between completers and drop-outs,Citation26,Citation28,Citation30,Citation31 two of them were assessed as having a high risk of bias.Citation26,Citation28 More than half of the included trials conducted intention-to-treat analyses.Citation27,Citation30,Citation31,Citation33

Table 2 Risk of bias ratings of the trials included in the systematic review

Effects of mindfulness-based interventions

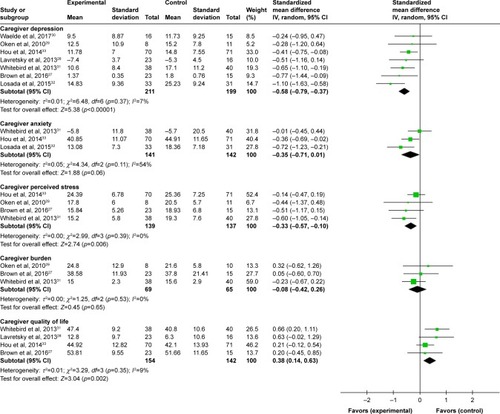

As presented in and , we reported the combined effects of mindfulness-based interventions compared to control conditions for dementia caregivers.

Table 3 Effect of mindfulness training for dementia caregivers

Effects of mindfulness training on depression of dementia caregivers

The pooled results showed that mindfulness training significantly decreased caregivers’ levels of depression (seven studies; 410 participants; SMD: −0.58, 95% CI: −0.79 to −0.37) compared with the control groups, with small heterogeneity across studies (I2=7%).Citation27–Citation33

Effects of mindfulness training on anxiety of dementia caregivers

The pooled effects of mindfulness training compared with controls in reducing caregivers’ levels of anxiety were not significant (three studies; 283 participants; SMD: −0.35, 95% CI: −0.71 to 0.01), with moderate heterogeneity across studies (I2=54%).Citation31–Citation33

Effects of mindfulness training on perceived stress of dementia caregivers

The combined results showed that compared with control conditions, mindfulness training significantly reduced perceived stress, with little heterogeneity across studies (four studies; 276 participants; SMD: −0.33, 95% CI: −0.57 to −0.10; I2=0).Citation27,Citation29,Citation31,Citation33

Effects of mindfulness training on caregiver burden

The advantage of mindfulness training was not significant in comparison with the controls, with little heterogeneity across studies (three studies; 134 participants; SMD: −0.08, 95% CI: −0.42 to 0.26; I2=0%).Citation27,Citation29,Citation31

Effects of mindfulness training on mental health-related quality of life of dementia caregivers

The effects of mindfulness training on enhancing the mental health-related quality of life were significant relative to controls, with small heterogeneity across studies (four studies; 296 participants; SMD: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.14 to 0.63; I2=9%).Citation27,Citation28,Citation31,Citation33

Discussion

Family caregivers of people with dementia are often under considerable stress, and conventional interventions may not always be effective or feasible in reducing distress of this vulnerable population. The present review was among the first meta-analyses to quantitatively assess whether mindfulness training, novel for its brevity and cost-effectiveness, could specifically benefit caregivers of individuals with dementia. Our review indicates that mindfulness training could potentially provide stress relief, depression management, and enhance quality of life of caregivers. No significant effect was found for alleviation of caregivers’ anxiety or burden associated with caregiving.

Mindfulness-based interventions have shown considerable success in improving mental health in a range of populations.Citation13–Citation15 The consistent and relatively strong level of efficacy across varied types of samples indicates that mindfulness training might enhance coping ability in every-day life and even under more extraordinary conditions of serious stress, such as caregiving. The results from the present meta-analysis, which focuses exclusively on caregivers of persons with dementia, are generally consistent with other reviews studying caregivers of individuals with advanced illness (included but not limited to dementia).Citation22–Citation24

The way in which mindfulness training affects several dimensions of psychological stress among caregivers is likely under debate but may originate from the following assumptions. First, caregivers of persons with dementia, under chronic stress for several years, could have difficulties changing their automatic and habitual ways of responding to round-the-clock caregiving.Citation45 Mindfulness-based treatments provide an opportunity for caregivers to be aware of their unhelpful reactions or thought patterns and then detach from this “automatic pilot”.Citation45 Second, there are few tangible solutions to many real-life scenarios when caring for elders with currently incurable diseases.Citation45 Non-judgmental acceptance,Citation46 an important element of mindfulness, can help participants “embrace” stressful caregiving as it is, but still enjoy a full and rich life.

More attention should be paid to effectiveness of mindfulness interventions on caregivers’ anxiety. Our pooled result showed a non-significant trend of benefit from mindfulness training (SMD: −0.35, 95% CI: −0.71 to 0.01; p=0.06), which was inconsistent with a significant finding (p<0.05) from another meta-analysis.Citation23 Another issue is that the available evidence studying anxiety has a considerable level of statistical heterogeneity (eg, I2>50% or Q=12.8).Citation23 The inconsistency, heterogeneity, as well as insufficiency of results in studying caregivers’ anxiety, potentially limit the strength of available evidence regarding beneficial effects of mindfulness programs on caregivers’ anxiety.

With regard to caregiver burden, we did not find a significant advantage of mindfulness training over controls in reducing burden associated with caregiving. One possibility is that caregiver burden is such a multicomponent measure (eg, the Zarit Burden Interview),Citation36 which includes both objective and subjective aspects of caregiving, that a brief intervention like mindfulness training can hardly target the multiple features represented by the concept of burden. Keeping in mind that included trials were insufficient and heterogeneous (eg, measures on burden), our result regarding caregiver burden should be treated very cautiously.

It is important to note that the promising mindfulness training seems well-accepted by dementia caregivers. At least 70% of participants completed all of the sessions in the mindfulness-based trials,Citation28,Citation30,Citation31 demonstrating reasonable adherence to the intervention. One included study arranged an orientation meeting to build enthusiasm at the beginning in addition to ongoing telephone calls and in-person contact throughout the intervention.Citation31,Citation47 Participants in another study learned to develop “an action plan” in the first class which encouraged them to practice activities following the intervention.Citation29 Of particular importance for future studies is to overcome the barriers of recruiting and retaining caregivers in novel interventions such as mindfulness training. Multi-pronged strategies may be needed, including the promotion of the benefit of this complementary therapy and full consideration of the role of busy family caregivers and their significant time commitment.

Finally, our study results should be weighted cautiously considering the relatively small number of trials that were included. Owing to variations in mindfulness training, our pooled results could have been influenced by heterogeneity across trials such as different content or forms of interventions. Moreover, the limited number of included trials make the power of meta-regression or subgroup analyses too low to explore potential effect modifiers which may contribute to heterogeneity across trials. Risk of publication bias can hardly be statistically assessed by tests for funnel plot asymmetry. As Cochrane Handbook suggested, the power of the tests is too low when less than ten studies are included in the meta-analysis.Citation48 Additionally, due to the limited number of investigations with follow-up data, the meta-analysis was restricted to the immediate effects post-intervention.

Despite these limitations, our results, based on the best available evidence (RCTs), show that mindfulness training is both potentially effective and feasible for reducing several domains of psychological stress in distressed caregivers of individuals with dementia. Given the promising results of our study, future large-scale and rigorously designed trials are needed to confirm our findings, especially for the specific effects of mindfulness in reducing caregiver burden or anxiety. Clinicians may consider mindfulness training as a brief and cost-effective alternative or adjunctive treatment to conventional interventions for dementia caregivers.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express sincere gratitude to Prof Linda Chiu-Wa Lam, Prof Sing Lee, and Prof Arthur Dun-Ping Mak for their patient guidance for this manuscript preparation.

Supplementary materials

Search strategy in this systematic review

Table S1 Search strategy in the Cochrane Library

Table S2 Search strategy in Medline, Medline In-Process, Embase, and PsycINFO

Table S3 Search strategy in the CINAHL Complete and Plus

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- PrinceMWimoAGuerchetMAliG-CWuY-TPrinaMWorld Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia. An Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Costs and TrendsLondonAlzheimer’s Disease International2015 Available from: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/statistics.htnrilAccessed August 24, 2017

- Alzheimer’s Association2016 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures12Alzheimer’s Association2016

- HaleyWEThe family caregiver’s role in Alzheimer’s diseaseNeurology1997485 Suppl 6S25S29

- SchulzRO’BrienATBookwalaJFleissnerKPsychiatric and physical morbidity effects of dementia caregiving: prevalence, correlates, and causesGerontologist19953567717918557205

- SchulzRBeachSRCaregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects StudyJAMA1999282232215221910605972

- JensenMAgbataINCanavanMMcCarthyGEffectiveness of educational interventions for informal caregivers of individuals with dementia residing in the community: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trialsInt J Geriatr Psychiatry201530213014325354132

- PinquartMSörensenSHelping caregivers of persons with dementia: which interventions work and how large are their effects?Int Psychogeriatr200618457759516686964

- WeinbrechtARieckmannNRennebergBAcceptance and efficacy of interventions for family caregivers of elderly persons with a mental disorder: a meta-analysisInt Psychogeriatr201628101615162927268305

- Gallagher-ThompsonDCoonDWEvidence-based psychological treatments for distress in family caregivers of older adultsPsychol Aging2007221375117385981

- BelleSHBurgioLBurnsREnhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: a randomized, controlled trialAnn Intern Med20061451072773817116917

- ElliottAFBurgioLDDecosterJEnhancing caregiver health: findings from the resources for enhancing Alzheimer’s caregiver health II interventionJ Am Geriatr Soc2010581303720122038

- Kabat-zinnJMindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and futureClinical Psychology Science and Pracicet2003102144156

- GoyalMSinghSSibingaEMMeditation programs for psychological stress and well-beingJAMA Intern Med2014174335736824395196

- GrossmanPNiemannLSchmidtSWalachHMindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysisJ Psychosom Res2004571354315256293

- KhouryBLecomteTFortinGMindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysisClin Psychol Rev201333676377123796855

- GrossCRKreitzerMJThomasWMindfulness-based stress reduction for solid organ transplant recipients: a randomized controlled trialAltern Ther Heal Med20101653038

- HendersonVPClemowLMassionAOHurleyTGDrukerSHebertJRThe effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on psychosocial outcomes and quality of life in early-stage breast cancer patients: a randomized trialBreast Cancer Res Treat201213119910921901389

- NakamuraYLipschitzDLKuhnRKinneyAYDonaldsonGWInvestigating efficacy of two brief mind-body intervention programs for managing sleep disturbance in cancer survivors: a pilot randomized controlled trialJ Cancer Surviv20137216518223338490

- ChhatreSMetzgerDSFrankIEffects of behavioral stress reduction transcendental meditation intervention in persons with HIVAIDS Care201325101291129723394825

- LeeSHAhnSCLeeYJChoiTKYookKHSuhSYEffectiveness of a meditation-based stress management program as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy in patientswith anxiety disorderJ Psychosom Res200762218919517270577

- ChiesaAMandelliLSerrettiAMindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus psycho-education for patients with major depression who did not achieve remission following antidepressant treatment: a preliminary analysisJ Altern Complement Med201218875676022794787

- HurleyRVPattersonTGCooleySJMeditation-based interventions for family caregivers of people with dementia: a review of the empirical literatureAging Ment Heathl2014183281288

- DharmawardeneMGivensJWachholtzAMakowskiSTjiaJA systematic review and meta-analysis of meditative interventions for informal caregivers and health professionalsBMJ Support Palliat Care201662160169

- JaffrayLBridgmanHStephensMSkinnerTEvaluating the effects of mindfulness-based interventions for informal palliative caregivers: A systematic literature reviewPalliat Med201630211713126281853

- LiGYuanHZhangWThe effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction for family caregivers: systematic reviewArch Psychiatr Nurs201630229229926992885

- HigginsJPAltmanDGGotzschePCThe Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trialsBMJ2011343d592822008217

- BrownKWCoogleCLWegelinJA pilot randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction for caregivers of family members with dementiaAging Ment Health201620111157116626211415

- LavretskyHEpelESSiddarthPA pilot study of yogic meditation for family dementia caregivers with depressive symptoms: Effects on mental health, cognition, and telomerase activityInt J Geriatr Psychiatry2013281576522407663

- OkenBSFonarevaIHaasMPilot controlled trial of mindfulness meditation and education for dementia caregiversJ Altern Complement Med201016101031103820929380

- WaeldeLCMeyerHThompsonJMThompsonLGallagher-ThompsonDRandomized controlled trial of Inner Resources meditation for family dementia caregiversJ Clin Psychol Epub201736

- WhitebirdRRKreitzerMCrainALLewisBAHansonLREnstadCJMindfulness-based stress reduction for family caregivers: a randomized controlled trialGerontologist201353467668623070934

- LosadaAMarquez-GonzalezMRomero-MorenoRCognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) versus acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for dementia family caregivers with significant depressive symptoms: results of a randomized clinical trialJ Consult Clin Psychol201583476077226075381

- HouRJWongSYYipBHThe effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction program on the mental health of family caregivers: a randomized controlled trialPsychother Psychosom2014831455324281411

- McNairDMLorrMDropplemanLFProfile of Mood StatesSan Diego, CAEducational and Industrial Testing Service1981

- CohenSKarmarckTMermelsteinRA global measure of perceived stressJ Heal Soc Behav1983244385396

- ZaritSHReeverKEBach-PetersonJRelatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burdenGerontologist19802066496557203086

- McHorneyCAWareJEJrLuJFSherbourneCDThe MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groupsMed Care199432140668277801

- WareJEJrSherbourneCDThe MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selectionMed Care19923064734831593914

- LamCLTseEYGandekBIs the standard SF-12 health survey valid and equivalent for a Chinese population?Qual Life Res200514253954715892443

- RadloffLSThe CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general populationAppl Psychol Meas197713385401

- SpielbergerCDGoruschRLLusheheRVaggPRJacobsGAManual for the State-Trait Anxiety InventoryMountain View, CAConsulting Psychologist Press1983

- HamiltonMA rating scale for depressionJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry196023566214399272

- TeriLTruaxPLogsdonRUomotoJZaritSVitalianoPPAssessment of behavioral problems in dementia: The Revised Memory and Behavior Problems ChecklistPsychol Aging1992746226311466831

- MontgomeryRJBorgattaEFSocietal and Family Change in the Burden of CareSingaporeThe National University of Singapore Press2000

- MackenzieCSPoulinPALiving with the dying: using the wisdom of mindfulness to support caregivers of older adults with dementiaInt J Health Promot Educ20064414347

- LindsayEKCreswellJDMechanisms of mindfulness training: Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT)Clin Psychol Rev201751485927835764

- WhitebirdRRKreitzerMJLewisBARecruiting and retaining family caregivers to a randomized controlled trial on mindfulness-based stress reductionContemp Clin Trials201132565466121601010

- SterneJAEggerMMoherDBoutronIAddressing reporting biasesHigginsJPChurchillRChandlerJCumpstonMSCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.2.0Cochrane2017