Abstract

Purpose

Time perspective (TP) is the term used to describe people’s preferences to focus on the past, present, and the future. Previous research demonstrates a link between TP and retirement planning. The objective of this study was to evaluate a TP-based online training intervention to improve retirement planning emphasizing the accumulation of resources.

Patients and methods

Twenty-two (M=59.41 years) working and fully retired participants were compared to a control group of 18 (M=56.67 years) participants. The intervention included three separate modules delivered online at the rate of one per week over a 3-week testing session. Outcomes focused on retirement goals and goal specificity.

Results

When compared to the control group, subjects in the intervention improved the number of goals relating to the accumulation of health (F(1,35)=10.15, P<0.01, 95% CI [0.28, 2.77]) and emotional resources (F(1,35)=5.16, P<0.05, 95% CI [−0.22, 2.37]). Goals relating to the accumulation of health resources also became more specific within the experimental group when compared to the control group and a significant interaction was recorded (F(1,38)=15.78, P<0.01, 95% CI [0.33, 1.74]). Similar interactions between the control and experimental groups were reported for the accumulation of cognitive resources (F(1,38)=13.15, P<0.01, 95% CI [0.28, 1.96]) and for emotional resources (F(1,38)=7.39, P<0.01, 95% CI [0.00, 1.50]). Qualitative feedback included recommendations to improve engagement by using more activities, providing clearer navigation instructions and avoiding the use of animation.

Conclusion

Applying a TP-based framework to the design of an online training intervention helped improve the accumulation and specificity of emotional and health resources for retirement. The study contains a number of theoretical and practical recommendations informing the design of future retirement planning interventions.

Introduction

According to a recent survey of retirement intentions by the Australian Bureau of Statistics,Citation1 there were almost a million people without a plan to retire, yet planning for retirement is a key requirement for securing wealth, improving positive psychological outcomes, and adjusting to retirement.Citation2 Equally important for retirement adjustment and satisfaction is ongoing planning during retirement.Citation3 Most of the research literature emphasizes preretirement planning although rarely in life are plans “set and forget” and retirement is no exception. The postretirement phase can be more financially precarious than preretirement because failure cannot be compensated and losses cannot be replaced. Planning ahead prior to workplace exit and continuing to plan during retirement can help to mitigate losses later in life.

In addition to an absence of planning, there is also evidence of a disconnect between broader goals and later implementation. For example, a large proportion of those people that do plan (34%) expect to exit the workforce by transitioning to part-time work yet the data suggest that people often exit more abruptly than anticipated and too early with insufficient funds.Citation1 One of the possible explanations for this is a lack of goal specificity, an essential ingredient for implementation intention and goal commitment.Citation4 According to Gollwitzer,Citation5 an implementation intention is a specific plan indicating when, where, and how individuals will carry out the intended action. By formulating an implementation intention, one’s mental representation of a specified situation can be activated and consequently the goal-directed action, when the situation is encountered, is efficient and conscious intent is not required; in other words, the action is automated.Citation6 It was proposed by Tubbs and EkebergCitation7 that goals and strategies may mutually influence each other because planning is useful for generating strategies under novel conditions and goal commitment may be influenced by engagement in planning.

In order to enhance the likelihood of successful goal attainment, effective planning and enactment of goal-oriented behaviors during the goal-striving phase are important.Citation8 The benefits of forming an implementation intention are empirically supported in laboratory settings.Citation9,Citation10 Furthermore, the benefits of implementation intention on self-regulating behavior have been demonstrated in promoting health behaviors including cervical cancer screening and repeated daily behaviors such as vitamin supplement use,Citation9 reducing unhealthy snacking habits,Citation11 managing diet,Citation12 and exercise.Citation13 The design of a retirement intention promoting implementation intention is yet to be tested in the retirement context. While many factors have been found to predict planning in retirement,Citation14–Citation18 a lesser explored areas have been time perspective (TP). TP refers to the importance a person places on the past, the present, or the future.Citation19 TP has been linked to retirement planningCitation20,Citation21 as well as retirement outcomes such as adjustmentCitation20 and therefore worthy of further consideration. Despite the numerous studies identifying factors predicting retirement planning and adjustment, there are very few researched interventions and no online interventions. The current study reports on the design and evaluation of an evidence-based online intervention using TP as a theoretical framework for the improvement of retirement planning behaviors.

Using time perspective as a theoretical framework

The relationship between age and TP, particularly future TP, has been well documented. While earlier research emphasized the importance of the relationship between age and TP,Citation22 more recent research suggests that the relationship between age and TP is less important than originally thought.Citation23–Citation25 Other recent longitudinal evidence suggests that TP is stable over time within individualsCitation15 operating more like a personality variable and that a single TP may dominate behavior throughout the life span.Citation26

Zimbardo and Boyd’s TP theoryCitation19 was employed as the relevant model for this study. According to the model, there are five different domains of TP displayed by individuals. A Present-Fatalistic TP is more likely to result in leaving things to chance, assuming that events are the result of fate. Participants with high Future-Focused TP often give up enjoyment of the present to focus on future rewards and goals. High scores on the Present-Hedonistic scale are associated with instant gratification at the expense of long-term goals. Participants with high Past-Negative or Past-Positive TP focus primarily on either negative or positive associations with the past.

The intervention uses number and specificity of goals as outcomes and incorporates previous evidence that 1) TP is linked to retirement planning, 2) TP is stable over time, and 3) TP acts more like a trait than a state. The design assumes TP to be relatively stable and emphasis is placed on understanding it and then applying it to retirement planning behavior.

Maximizing distribution and remote access

The Internet provides enormous opportunities to distribute information and engage in online learning. Developing online learning interventions has the potential to help people when they need it most, regardless of their location.Citation27 Stereotypes about older people and access to technology may prevent researchers from exploring this mode of delivery but in Australia, 83% of people aged 55–64 years were regular Internet users and the total number of households with Internet access continues to increase from 60% in 2005 to >85% 10 years later.Citation28 We opted for an online intervention with an eye to the future for Australian workers. A review by du Plessis et alCitation27 provided numerous insights to inform the training design for older learners. Some of their recommendations incorporated into the design included providing learners with one module to complete each week allowing self-determining the pace of learning, optimizing a time free of distractions; providing individualized feedback on TP that was incorporated into their training, and enabling use of familiar technology so they could make adjustments customized to their needs (eg, increased screen size).

Measuring intervention success: outcomes

Goals act as a motivational source in retirement because they help the individual visualize their future wants and needs.Citation3 Setting goals is considered a fundamental precursor to planning for retirementCitation21 and consequently retirement well-being. In creating a detailed strategy to attain goals, there is a higher likelihood of goal success. To determine the efficacy of an individual’s current goal setting, there are two measures of interest – the number of goals and the specificity of goals. Clarity of retirement goals is significantly associated with retirement planning behavioursCitation29 and thus if one begins to set clear goals then he or she is more likely to plan pre- and postretirement.

Participants in the current study were educated on evidence-based goal-setting techniques and were required to list goals under five subheadings derived from the Dynamic Resource Model of Retirement.Citation18 These different subheadings were commensurate with the Retirement Resources Inventory,Citation16 including “wealth”-related goals, “health”-related goals, and “social”-related goals, goals on keeping “cognitively active”, and goals on keeping “emotionally well”. While planning for retirement has been shown to facilitate improved satisfaction,Citation30 there is also evidence to suggest that an underpinning mechanism driving this relationship could be an individual’s sense of environmental mastery.Citation3

Incorporating elements of Kirkpatrick’s training evaluation model,Citation31 we also sought to understand whether participants learned about TP during the intervention and whether they gained insight into their and others behavior. Kirkpatrick’s modelCitation31 emphasizes evaluation across four levels: reaction (did people enjoy the training?), learning (did they gain knowledge?), behavior (did they change their behavior?), and results (did training produce the final results or outcomes expected?). It was hypothesized that the intervention would increase participants’ number and specificity of goals (behavior) and help them to better understand TP and how it related to them (learning) while enjoying the experience (reaction). It was beyond the scope of this study to determine whether goals were implemented (results).

Patients and Methods

Study design

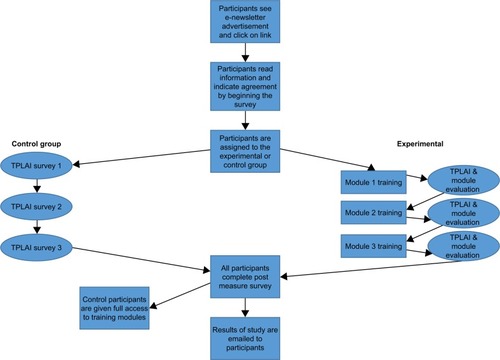

The present study is a mixed between-within design, using a combination of qualitative and quantitative measures, to examine the influence of an online training intervention on planning behavior for retirement (). Ethics approval for the study was provided by the University Human Research Ethics Advisory Panel (Psychology). Before beginning, the study participants read an information statement and indicated their agreement to participate by clicking on the link provided. The ethics consent included participant selection and purpose of the study, a description of the study and any associated risks, confidentiality, and disclosure of information. Participants were free not to participate or withdraw from the study at any time without prejudice.

Participants

The total sample contained 40 participants, 15 (37.5%) male and 25 (62.5%) female, ranging between 45 and 77 years of age (M=58.17). In line with earlier findings that pre- and postplanning are equally important people who were working, fully retired and partially retired participants were all eligible for participation. The 40 participants were assigned to either the experimental n=22 (10 male) or control condition n=18 (5 male). The control group was essentially waitlisted receiving only the same pre- and posttests as the experimental group. Details are shown in . Within each condition, 14 participants identified themselves as still working with the remainder nominated as retired.

Please contact the corresponding author for supplemental materials and detailed examples of training materials.

Training modules

Examples of the training materials used can be accessed here: https://www.researchgate.net/project/Time-Perspective-based-interventions-to-improve-retirement-planning.

A more detailed description of each module appears below.

Training module 1

This module outlined the purpose of training and emphasized the importance of planning, its link to retirement outcomes as well as differences in expectations of retirees vs reality. For examples, many people believe they will live off their investments in retirement although a majority will need a state-provided pension. As part of the first module, experimental participants were provided with a Feedback Report detailing their most dominant TP and their results on the Retirement Resources Inventory. The modules were designed to be equally applicable to people pre- and postretirement. For preretirees, the message was to try accumulate resources before they leave work while the message for retirees was to normalize behavior and encourage people to keep planning.

Training module 2

The main objective of module 2 was to improve participants understanding of TP and have them identify how it may influence their propensity to plan for retirement. There were three main parts to this module: 1) understanding TP theory, 2) considering their retirement resource accumulation to date, and 3) the link between TP and their planning behavior.

Training module 3

The main objective of the third module was to integrate all the information learnt from previous modules (such as the importance of resource accumulation and understanding the theory of TP) in order to encourage new goal-setting behaviors. Reference was made to the SMART modelCitation32 emphasizing the need for goals to be Specific, Measureable, Attainable, Realistic, and Timely.

Measures

Retirement planning and certainty

Participants responded to a number of questions to better determine their retirement status and future plans. They were asked: “Are you fully retired?” (select one) and responded “No” or “Yes”; “What age do/did you expect to retire?” (open ended); and “How certain are/were you that you will retire at this age?” (answered with 0–100%).

Time perspective

Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (ZTPI)Citation19 is a self-report 56-item measure that is used to identify an individual’s TP. The ZPTI has five individual subscales: Past-Positive (0.80), Past-Negative (0.82), Present-Hedonistic (0.79), Present-Fatalistic (0.74), and Future-Focused (0.77). The reliabilities as reported by the original authors are reported in parentheses; due to sample sizes, reliability coefficients were not reported in this study.

Number and specificity of goals set

The methodology used by Petkoska and EarlCitation21 was applied to measure the number and specificity of current goals. Participants listed their retirement goals under five resource categories, namely wealth, health, social, cognition, and emotional. For each participant, two scores (number of goals and specificity of goals) were calculated under each goal category.

Goal specificity was analyzed using a Grounded Theory approach to qualitative data analysis.Citation33,Citation34 Participants were invited to prepare goal statements. The statements were rated by two separate raters in relation to goal specificity. The scores of the two raters were compared to cross-validate results. Goals that included no specific component, for instance, “exercise more”, were scored a 0. Goals that included four specific components, for instance, “tomorrow at 3 pm (1) I will contact a trainer (2) to help me exercise twice a week (3) so I can run five kilometers (4)” were scored a 4. When ratings of the two raters were compared, and there was a difference of 1.5 points or more (ie, where they failed to reach agreement), these items were rejected from analysis. Scores of both raters ranged from 0 to 4.

Time perspective learning and insight

There were two subscales within this measure: a learning component and an insight scale. The learning component focused on testing how much the participants had learned about TP. A typical item included: “For people with high scores on Past Negative, their childhood sights, sounds, and even smells often bring back a flood of wonderful memories” (negatively scored). There were five such items, scored as either True or False resulting in a total score out of 5. The five insight items focused on the extent to which participants had applied TP in analyzing their own behavior or the behavior of others. A typical item included was “I can recognize how people around me differ in their Time Perspectives”. These items were scored on a 5-point scale from very false (1) to very true (5). Scores were added and averaged to provide an overall score out of 5.

Results

Preliminary analysis

The mean age of participants in the sample was 58.18 (SD=8.2) years and the mean expected age of retirement for those not yet retired was 63.10 years (SD=4.8). Furthermore, participant’s certainty of retirement age for the unretired portion sample was 71.49%. This indicated that, on average, participants were mostly sure they would retire at their anticipated age.

Improvements in number of goals

represents the mean and SDs for the number of goals set by participants in each condition, across time. Results indicate that the intervention had an effect on the number of goals set by participants relating to “health” and “emotions”.

Table 1 Mean and SD scores for number of goals by condition and across time

It should be noted that for health-related goals (ie, lose 5 kilos before Christmas), experimental participants, on average, increased in the number of goals from time 1 to time 2. The control participants, on average, decreased in their number of goals set between time 1 and time 2. Such findings were supported by the statistically significant difference between time 1 (M=2.15, SD=1.35) and time 2 (M=3.35, SD=1.18) in the experimental condition for goals (F(1,35)=10.15, P<0.01, 95% CI [0.28, 2.77]). These findings are supported by a significant interaction. Results show a greater increase in the experimental condition than the control on emotion-related goals (F(1,35)=5.16, P<0.05, 95% CI [−0.22, 2.37]).

Improvements in specificity of goals

The means and SD scores for participants by condition and across time for specificity of set goals can be found in . Scores vary between conditions on each category of goals and across time. Participants in both conditions reported a specificity of around 1.5 on health-related goals at time 1. However, participants in the experimental condition considerably increased the specificity of their goals set at time 2. This interaction was found to be statistically significant (F(1,38)=15.78, P<0.01, 95% CI [0.33, 1.74]), an outcome that supports the inference that the training intervention worked to increase participants’ specificity of health-related goals at time 2.

These results indicate that there is a substantial difference between specificity of goals relating to the accumulation of cognitive resources set by participants in the experimental condition at time 2. In , it can be seen that the specificity of goals for both conditions is approximately the same at time 1; however, at time 2, the experimental condition substantially increased in specificity of goals, as compared to the control that appears to remain steady. It was found that this interaction is significant (F(1,38)=13.15, P<0.01, 95% CI [0.28, 1.96]).

Significant improvements were also reported in emotion-related goals. At time 1, the specificity of emotion-related goals is the same for both conditions, whereas at time 2, the experimental condition substantially increases in goal specificity. It appears that the specificity of emotion-related goals remains steady, even decreasing. This difference was statistically significant (F(1,38)=7.39, P<0.01, 95% CI [0.00, 1.50]).

Changes in time perspective learning

Participants in the experimental condition and control condition increased their TP learning when tested after module 2 in comparison to modules 1 and 3. The experimental condition increased from 4.36 to 4.68. However, from modules 2 to 3, the means remain relatively steady. The Bonferroni contrast for this analysis was FC=F0.05; 1, 38=4.098.

Changes in time perspective insight

The experimental condition had a statistically higher level of TP insight – (F(1,38)=6.28, P<0.05, 95% CI [0.28, 2.66]) – than participants in the control condition averaging across modules.

Module evaluation

The mean and SD scores for these evaluations can be found in . Engagement in the training progressed over the course of the three modules. Examination of participant’s open-ended feedback for all modules allows three themes of possible improvement to emerge: 1) restructuring the content to include more activities and exercises in module 1, 2) clarifying instructions about how to navigate the site, and 3) adjusting the design to be more age appropriate for the group (ie, more use of photos and less use of cartoons). Positive aspects of the training highlighted were 1) the use of embedded video footage where the researcher talked about TP, 2) the appeal of an interactive design, and 3) the opportunity to gain a new perspective on themselves and others (ie, strengths training). Overall, the feedback provided through evaluation is critical to the development of this research and should be incorporated into the design of future interventions.

Table 2 Mean and SD scores for module evaluation

Discussion and conclusion

The current study sought to expand the retirement literature in two ways: first, by designing and testing an evidence-based intervention for the improvement of retirement planning behavior using TP as a theoretical framework and second, to inform the development of future interventions by evaluating the training modules used in the study.

Intervention effectiveness

It was hypothesized that the intervention would increase participants’ number and specificity of goals (in Hypotheses 1 and 2). The results indicated that participants assigned to the experimental condition showed an increase in the number and specificity of retirement goals (in areas relating to health, social needs, and emotional needs).

Improvements in time perspective learning and insight

Consistent with the hypothesis, there was evidence of learning from participation (in Hypothesis 3) as well as greater insight into their own and other’s behavior (in Hypothesis 4).

Limitations and future recommendations

As discussed, the relatively short timeframe hindered the collection of data relating to resource accumulation. Given that existing research highlights the gradual acquisition of retirement resources,Citation18 it would be useful to measure these variables at a 6- to 12-month delay. It is also recommended that the researchers tease apart the different elements (ie, the use of feedback with and without training) incorporated into the comprehensive design. For example, a future research project could include a third condition entitled “feedback only”, whereby participants do not receive the intervention but only the feedback report detailing dominant TPs. This condition would allow inferences to be made regarding the singular impact of the feedback on participants’ planning behaviors.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [webpage on the Internet]Retirement and retirement intentions Australia 2016 to June 2017 (Release Number 6238)2018 Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/6238.0Accessed November 26, 2018

- DonaldsonTEarlJKMuratoreAMExtending the integrated model of retirement adjustment: incorporating mastery and retirement planningJ Vocat Behav2010772279289

- TopaGMorianoJADepoloMAlcoverCMMoralesJFAntecedents and consequences of retirement planning and decision-making: a meta-analysis and modelJ Vocat Behav20097513855

- DiefendorffJMLordRGThe volitional and strategic effects of planning on task performance and goal commitmentHum Perform2003164365387

- GollwitzerPMGoal achievement: the role of intentionsEur Rev Soc Psychol199341141185

- BarghJAChenMBurrowsLAutomaticity of social behavior: direct effects of trait construct and stereotype activation on actionJ Pers Soc Psychol19967122302448765481

- TubbsMEEkebergSEThe role of intentions in work motivation: implications for goal-setting theory and researchAcad Manage Rev1991161180199

- GollwitzerPMImplementation intentions: strong effects of simple plansAm Psychol1999547493503

- AjzenICzaschCFloodMGFrom intentions to behavior: implementation intention, commitment, and conscientiousnessJ Appl Soc Psychol200939613561372

- BrandstätterVLengfelderAGollwitzerPMImplementation intentions and efficient action initiationJ Pers Soc Psychol200181594696011708569

- TamLBagozziRPSpanjolJWhen planning is not enough: the self-regulatory effect of implementation intentions on changing snacking habitsHealth Psychol201029328429220496982

- AdriaanseMAVinkersCDDe RidderDTHoxJJDe WitJBDo implementation intentions help to eat a healthy diet? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical evidenceAppetite201156118319321056605

- Bélanger-GravelAGodinGAmireaultSA meta-analytic review of the effect of implementation intentions on physical activityHealth Psychol Rev2013712354

- AgnewJBatemanHThorpSFinancial literacy and retirement planning in AustraliaNumeracy201362125

- EarlJKArchibaldHRetirement planning is more than just accumulating resourcesEur J Manag2014142136

- LeungCSYEarlJKRetirement resources inventory: construction, factor structure and psychometric propertiesJ Vocat Behav2012812171182

- LusardiAMitchellOSThe economic importance of financial literacy: theory and evidenceJ Econ Lit201452154428579637

- WangMProfiling retirees in the retirement transition and adjustment process: examining the longitudinal change patterns of retirees’ psychological well-beingJ Appl Psychol200792245547417371091

- ZimbardoPGBoydJNPutting time in perspective: a valid, reliable individual-differences metricJ Pers Soc Psychol199977612711288

- EarlJKBednallTCMuratoreAMA matter of time: why some people plan for retirement and others do notWork Aging Retire201512181189

- PetkoskaJEarlJKUnderstanding the influence of demographic and psychological variables on retirement planningPsychol Aging200924124525119290760

- KooijDBalPMKanferRFuture time perspective and promotion focus as determinants of intraindividual change in work motivationPsychol Aging201429231932824956000

- BohnLKwong SeeSTFungHHTime perspective and positivity effects in Alzheimer’s diseasePsychol Aging201631657458226974590

- GrühnDSharifianNChuQThe limits of a limited future time perspective in explaining age differences in emotional functioningPsychol Aging201631658359326691300

- Tasdemir-OzdesAStrickland-HughesCMBluckSEbnerNCFuture perspective and healthy lifestyle choices in adulthoodPsychol Aging201631661863027064600

- GuptaRHersheyDAGaurJTime perspective and procrastination in the workplace: an empirical investigationCurr Psychol2012312195211

- du PlessisKAnsteyKJSchlumppaAOlder adults’ training courses: considerations for course design and the development of learning materialsAust J Adult Learn201151161174

- Australian Bureau of Statistics [webpage on the Internet]Household use of information technology, Australia, 2016 17 (Release Number 81460) Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/8146.02016-17?OpenDocumentAccessed November 26, 2018

- StawskiRSHersheyDAJacobs-LawsonJMGoal clarity and financial planning activities as determinants of retirement savings contributionsInt J Aging Hum Dev2007641133217390963

- BatemanHDeetlefsJDobrescuLINewellBROrtmannAThorpSJust Interested or getting involved? An analysis of superannuation attitudes and actionsEcon Rec201490289160178

- KirkpatrickDLEvaluating Training Programs: The Four LevelsSan FranciscoBerrett-Koehler1994

- BachiochiPDWeinerSPQualitative data collection and analysisRogelbergSGHandbook of Research Methods in Industrial and Organizational PsychologyOxfordBlackwell2004161183

- ConzemiusAO’NeillJThe Power of Smart Goals: Using Goals to Improve Student LearningIndianaSolution Tree Press2005

- CharmazKGrounded theoryQual Psychol2003181110