?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Background

Several studies have reported the potential value of the dual-task concept during locomotion in clinical evaluation because cognitive decline is strongly associated with gait abnormalities. However, current dual-task tests appear to be insufficient for early diagnosis of cognitive impairment.

Methods

Forty-nine subjects (young, old, with or without mild cognitive impairment) underwent cognitive evaluation (Mini-Mental State Examination, Frontal Assessment Battery, five-word test, Stroop, clock-drawing) and single-task locomotor evaluation on an electronic walkway. They were then dual-task-tested on the Walking Stroop carpet, which is an adaptation of the Stroop color–word task for locomotion. A cluster analysis, followed by an analysis of variance, was performed to assess gait parameters.

Results

Cluster analysis of gait parameters on the Walking Stroop carpet revealed an interaction between cognitive and functional abilities because it made it possible to distinguish dysexecutive cognitive fragility or decline with a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 94%. Locomotor abilities differed according to the group and dual-task conditions. Healthy subjects performed less well on dual-tasking under reading conditions than when they were asked to distinguish colors, whereas dysexecutive subjects had worse motor performances when they were required to dual task.

Conclusion

The Walking Stroop carpet is a dual-task test that enables early detection of cognitive fragility that has not been revealed by traditional neuropsychological tests or single-task walking analysis.

Introduction

Several authors have reported a causal relationship between the single-task motor abilities of older subjects and an advanced stage of dementia. Analysis of single-task walking as an evaluation tool and prediction of dementia pathology represents a recent approach in the literature.Citation1,Citation2 However, clinical and therapeutic interest appears to be more in early detection of mild cognitive impairment, given that this is often associated with the prodromal phases of several dementia pathologies, eg, Alzheimer’s disease, and frontotemporal and vascular dementia. The annual rate of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia ranges from 5% to 50%, depending on the cognitive profile of subjects and the etiology of dementia.Citation3 Several authors have reached a consensus, placing the concept of mild cognitive impairment within a stable nosologic framework (mnesic complaint by the patient or his/her family members without repercussions on daily life, an absence of dementia), despite the heterogeneity of its population.Citation4,Citation5 In 2011, Erk et alCitation6 demonstrated that mnesic complaints in older patients were associated with structural and functional modification of the hippocampus, whereas cognitive impairment has yet to be objectified by neuropsychological tests. Therefore, diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment more particularly relies on early detection of dysexecutive and mnesic impairment. However, traditional tests appear to be inadequate for early detection of cognitive impairment at high-risk of progression to dementia. There are multiple reasons for this, ie, use of neuropsychological tests that are not sensitive enough, unsuitable norms, cognitive reserve, and/or underestimated compensation mechanisms.

The relationship between motor performance and cognitive ability can be investigated using the dual-task concept. Identification of cognitive resources (executive function or attention) engaged during dual-tasking triggers a reduction in walking speed in older subjects,Citation7–Citation10 and even cessation of walking in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease.Citation11 Executive function refers to a variety of higher cognitive processes. Several authors have demonstrated the value of analysis of walking stability and variability as a tool for detection of cognitive impairment, beginning at the mild cognitive impairment stage because the motor profiles of these subjects have similarities to those of patients with Alzheimer’s disease in single-taskingCitation12 and dual-tasking,Citation13 whereas their motor abilities are significantly different from those in young and older healthy subjects for single-tasking and dual-tasking.Citation14–Citation16

In everyday activities, there are numerous dual-task locomotor situations that require active involvement of the visual system. Nevertheless, few studies have been performed on the ability to walk according to visuospatial information. In 2011, Al Yahya et alCitation17 described numerous dual-tasking situations based on working memory exercises, decision-making, and verbal fluency. Likewise, they enumerated various spatiotemporal parameters of walking used to evaluate dual-task motor performance (eg, speed, frequency, length of stride). Executive function is often implicated in dual-task situations because subjects must walk and adapt to new and/or complex situations. These include several cognitive situations, such as working memory, mental inhibition, and mental flexibility.Citation18

In 2008, Yogev-Seligmann et alCitation19 proposed a theoretical framework showing how changes in different aspects of executive function (volition, self-awareness, planning, inhibition of dominant response and external distraction during response control, dual-task coordination) can modify gait patterns. They also reviewed studies indicating a significant link between gait and executive function, in particular, during dual-task situations. However, most studies of dual-tasking have been limited to evaluation of linear gait and are associated with one of two verbal tasks, ie, counting backwards (working memory) or listing animal names (semantic memory).Citation13,Citation15,Citation16,Citation20,Citation21 Therefore, other cognitive functions, such as the mental inhibition concept in dual-tasking, have been little studied. Nevertheless, in 2007, Fournet et alCitation22 reported early deficits in inhibition at an attentional level in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. The increased sensitivity to interference seen in such individuals is commonly revealed during the Stroop test. This selective attention task, which consists of inhibiting an automatic verbal response, is markedly reduced in older people with mild cognitive impairment compared with healthy older people.Citation23–Citation25 On the other hand, while there are numerous adaptations of the Stroop test based on the interference effect proposed by Stroop in 1935, very few studies have been done using the Stroop test in the context of dual-tasking,Citation26–Citation28 and to our knowledge, none has used a spatial navigation task. However, several authors have shown that an environmental version of Stroop provides a better indication of the cognitive abilities of subjects compared with standard tests.Citation29,Citation30

The aim of this work was to devise a dual-task test that can be used for early detection of mild cognitive impairment. By adapting the Stroop color word test to walking, we also attempted to determine if the ability to integrate visual information during dual-tasking could be modified by the effects of aging and/or cognitive status.

We hypothesized that a new dual-task approach could refine the diagnosis of cognitive impairment in its very early stages, which cannot be detected by a single-task walking test or by a traditional paper–pencil neuropsychological test. It would then follow that older subjects with mild cognitive impairment have an altered ability to integrate visual information during dual-tasking, indicated by a reduction in their dual-task walking performance.

Materials and methods

Population

Our study population was made up of 14 young subjects (mean age 21.1 [20–30] years), 18 older adults (mean age 69.3 [64–74] years), and 17 very old adults (mean age 81.3 [75 onwards] years). The subjects over 65 years of age were recruited from cultural associations. Inclusion criteria were: willingness to participate in the study, living in a noninstitutional environment, and ability to get around without technical assistance on a daily basis. Exclusion criteria were: a cognitive complaint with repercussions on daily functional ability, uncorrected visual impairment, neurologic pathology (eg, Parkinson’s disease, stroke), orthopedic surgery to the lower limbs, depression, and being on medication that could influence posture and/or gait.

Clinical and cognitive evaluation

Subjects were assessed by a doctor for inclusion and exclusion criteria. All of the subjects then underwent a battery of rapid cognitive impairment tests by a neuropsychologist using the Mini Mental State ExaminationCitation31 and the Frontal Assessment Battery.Citation32 Mood and depression were tested using the Geriatric Depression Scale.Citation33 Daily and functional activities were also evaluated using the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living test.Citation34

Executive and mnesic functioning was evaluated by the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) III,Citation35 the Trail Making Test (TMT),Citation36 the Stroop color–word test,Citation37 and the five-word test.Citation38 Only the working memory part of the WAIS III was retained for its ability to formulate and resolve mental problems. The TMT is a pencil–paper test which consists of linking targets as quickly as possible in numeric order (1–25) in Part A and alternating between numbers and letters in Part B. It evaluates visual attention in Part A and mental flexibility in Part B. The Stroop color–word test is a test of mental inhibition of selective attention. It is made up of three parts. The first part consists of reading the names of colors printed in black ink; in the second part, the subject is asked to name colors in rectangles; and in the third part, the subject reads the color of the words aloud. The subject must name a maximum of items for each page in 45 seconds. The five-word test is a rapid mnesic test using five words with immediate and deferred recall which can be indexed.

Single-task walking

We performed a motor evaluation of single-task spontaneous walking for 10 m in a normal environment on an 8 m electronic walkway (GAITRite®, CIR Systems Inc, Sparta, NJ, USA). This tool is equipped with a portable, pressure-sensitive electronic walkway (793 cm × 61 cm × 0.6 cm [L × W × H]), so recording of spatiotemporal gait parameters does not include the acceleration and deceleration phases. In order to have a value that is representative of single-task motor ability, subjects were asked to walk five times at their own pace.

Dual-task walking

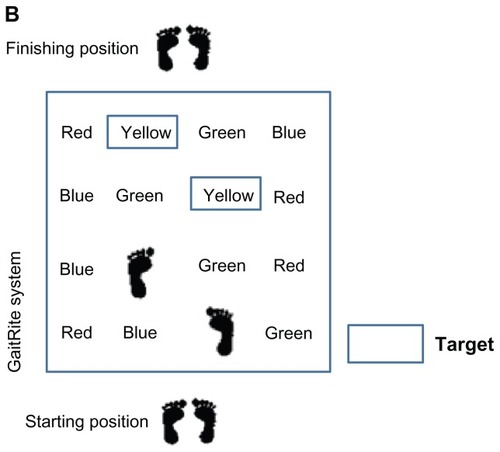

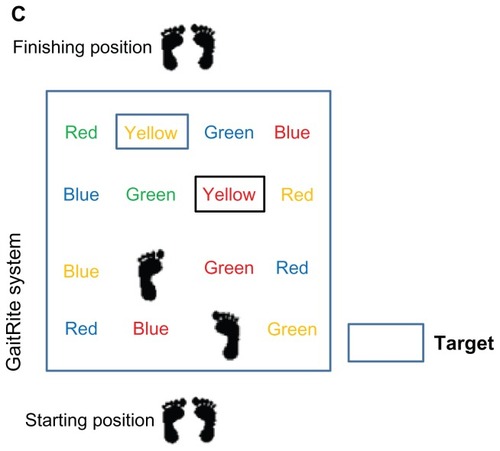

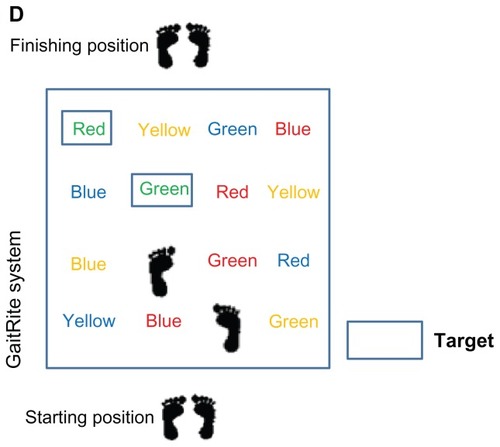

We used an adapted version of the Stroop color–word paper–walking test (dual-task) with the Walking Stroop carpet (WSC) in order to create a visuospatial dual-task based on the Stroop interference effect (). This test was developed by our team in our motion analysis laboratory. The WSC is a dual-task motor test during which the subject steps on targets on a 5 m long removable cloth support on an electronic walkway. This system records all gait parameters during Stroop visuospatial adaptation to dual-tasking. Each removable support is associated with different pages of the Stroop color–word test. However, the methodological constraints of this dual-task test have brought about modifications to the original version. The principal adaptation is the form of restoration of the dual-task response. In fact, the WSC requires a motor response because the subject must step on targets on the ground whereas the response is verbal in the table version. The targets are set up like the Stroop Victoria test,Citation39 ie, the stimuli are presented in lines of four different words and/or colors (red, yellow, blue, and green). Before giving the green light, the examiner informs the subject that a word or color will remain unchanged during the entire test. Each line has only one correct answer and thereby forms a circuit of 15 targets over a distance of 5 m. The mean distance between targets of 45 cm enables all subjects to go from one target to another without difficulty. Each condition is defined so that subject steps do not get crossed (–).

Figure 1B First condition: DTB&W.

The conditions are associated with the stages of the Stroop color–word test and performance of the test is always in the same order. Thus, there is one congruent situation followed by two incongruent situations. The first condition, DTB&W (dual-taskblack&white) consists of walking on the word corresponding to the name of a color (). If the subject is supposed to walk on the word “green”, on each line, he/she must spot the target and refrain from reading the other words (red, yellow, blue). In this condition, the carpet is black and the targets are white in order to increase the contrast and reduce the risk of instability linked to the treatment of information. Indeed, in 1991, Lord et alCitation40 demonstrated that a reduction in the ability to distinguish characters with low contrast was a strong predictor of the risk of falling. The second condition, DTword consists of walking on a word that is written in several different colors (). If the instructions are to walk on the word “blue”, the subject must avoid the color of the word and the other words (green, yellow, red). The third condition, DTcolor is the paper–pencil test interference situation, which consists of walking on words written in a color and avoiding reading the words (). If the instructions are to walk on the color red, the subject must avoid reading the words and not walk on the other colors (blue, yellow, green). In this condition, the targets on the colored carpet can be congruent (the word “red” is written with red ink) or incongruent (the word “green” is written in red ink) in the second and third conditions. We asked subjects to perform the test under each condition twice, ie, reading DTB&W reading colored DTword and spotting DTcolor.

Figure 1C Second condition: DTWord.

Note: In that condition, the subject has to read and to walk on the word “yellow”.

Figure 1D Third condition: DTColor.

Subjects received the following instruction to perform the two tasks as best they could: “Walk as fast as possible and do the Stroop exercise without making any mistakes.” However, no priority was given to one domain or the other. Each condition had a familiarization and learning phase over a distance of 2 m, which was repeated until the subject understood the task to be accomplished (a maximum of three repetitions were necessary). During the test, the result was correct from the moment the subject placed a part of his/her foot on the correct target. Each condition was filmed by a webcam (640 × 480) that was synchronized with the electronic walkway in order to detect errors accurately. Because the positions of the targets were predetermined according to the task, the subjects were not able to retain their usual gait parameters such as stride length, distance, and variability of stride. Therefore, we were able to focus on the following parameters: velocity, frequency, time in double support, gait cycle time, and number of steps.

Statistical analysis

In the first instance, the aim was to detect the possible existence of types of behavior linked to the motor task. This required a statistical analysis in order to assess the groups solely on their gait characteristics during single-tasking and/or dual-tasking. The ascendant hierarchic classification method or cluster analysis (Ward’s method,Citation41 Euclidean distance) regroups subjects according to their functional similarities by using spatiotemporal parameters of walking during single-tasking and dual-tasking. We averaged five tests in single-tasking and two tests for each dual-tasking condition to obtain a single representative value per variable and per walking condition in the cluster analysis. A one-way analysis of variance followed by a post hoc Tukey’s test was then used to determine the differences between the groups for the different gait parameters. Next, a Student’s t-test of the different neuropsychological tests was performed to reveal any differences in the cognitive profiles for each group.

The differences between dual-tasking conditions and gait parameters for each group were determined by one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance followed by a post hoc Tukey’s test. The statistical analysis was performed using Statistica version 9 (Statsoft Inc, Tulsa, OK, USA) software with a significant difference if P < 0.05.

The sensitivity and specificity of the WSC to detect subjects with mild cognitive impairment were calculated as follows:

Low performance refers to the motor performance of subjects in the group with the largest deficit in WSC, and high performance refers to the group with the best gait parameters in dual-tasking. Given that this test is new and no similar study has been reported, there are no reference values.

Results

Cognitive assessment

The results of the neuropsychological Instrumental Activities of Daily Living and Geriatric Depression Scale tests identified a group of 25 healthy subjects (14 young, 11 older or elderly healthy adults) and 15 subjects with mild cognitive impairment who were divided into subgroups according to the criteria devised by Petersen,Citation4 ie, six with amnesic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI), three with nonamnesic mild cognitive impairment and impairment of executive function only (naMCI), and six with multiple-domain amnesic mild cognitive impairment (mdMCI). We noted and differentiated nine subjects without cognitive decline but whose performance on executive function tests was always at the limit of the pathologic threshold. These subjects formed another group deemed to have borderline mild cognitive impairment (blMCI), given their common characteristics.Citation30

Single-task walking

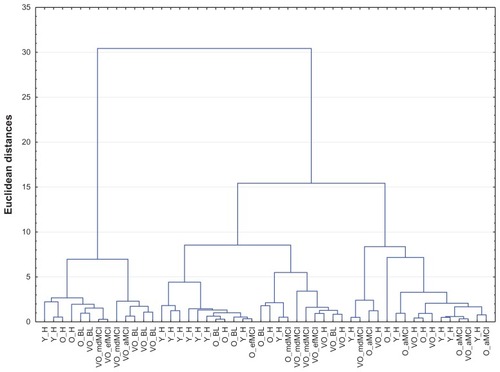

The first cluster analysis () was performed on the five single-task parameters (velocity, frequency, number of steps, gait cycle time, time in double support) which were identical to those retained for dual-task conditions. Before proposing a classification on the basis of dual-task conditions, it was important to analyze these same parameters during single-task conditions in order to determine their impact on the formation of groups. For this cluster analysis, we did not differentiate distinct branches, the R ratio calculation,Citation42 did not identify groups, and the Euclidean distance was too small to match subjects by their motor performances in homogeneous groups. Therefore, these gait variability and stability parameters failed to identify distinct groups.

Figure 2 Gait pattern Dendogram of the ST.

Abbreviations: Y, Young; O, Older; VO, Very Older; H, Healthy; BL, Borderline MCI; naMCI, non-amnesic MCI executive impairment only; aMCI, amnesic MCI; mdMCI, multiple-domain amnestic MCI.

Dual-task walking

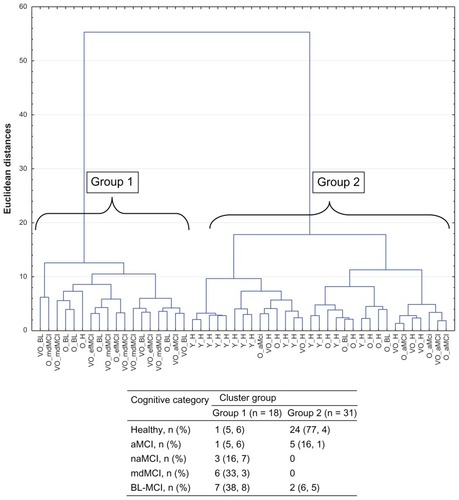

The second cluster analysis () sought a relationship between single-task and dual-task WSC parameters. Classification using the ascendant hierarchic method revealed two distinct branches, with a Euclidean distance of less than 20 and a reunification at 55 (). The R ratio calculationCitation40 identified two distinct walking patterns from all of the subjects’ results (limited to 10).

Figure 3 Gait pattern Dendogram of the ST and WSC.

Abbreviations: Y, Young; O, Older; VO, Very Older; H, Healthy; BL, Borderline MCI; naMCI, non-amnesic MCI executive impairment only; aMCI, amnesic MCI; mdMCI, multiple-domain amnestic MCI.

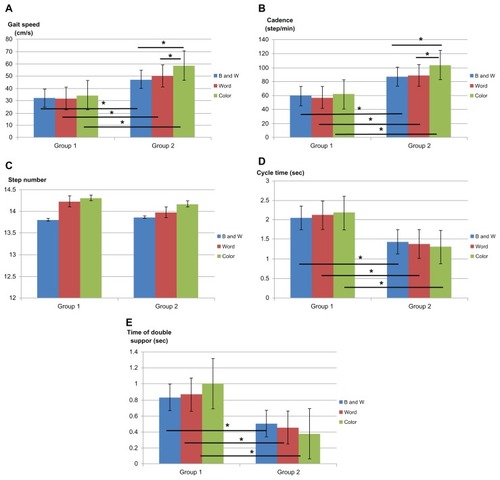

The two groups were functionally differentiated by the overall effect of analysis of variance (F = 9.2; P < 0.001). Group 1 subjects (with diminished executive function or cognitive fragility) walked more slowly than group 2 subjects (healthy subjects with or without mild amnesic cognitive impairment) under single-task conditions (F = 4.97; P = 0.03) and under dual-task conditions (F = 56.71 to 64.14; P < 0.001, ). There were no differences between the groups for the other single-task parameters. In dual-tasking, motor performances in group 1 were lower than those in group 2 (), except for the number-of-steps parameter, where there was no significant difference (). However, the number of steps could indirectly provide an indication of the number of errors, but we noted that group 1 subjects did not make more errors than subjects in group 2 (F = 3.21, P = 0.12, ).

Table 1 Number of errors in all conditions in DT

Detection of mild cognitive impairment

The second cluster analysis revealed the existence of two groups. We studied the cognitive performance of each individual in order to determine if the groups formed principally from gait parameters were also differentiated on a cognitive level (). Group 1 included 18 subjects (seven older adults, 11 very old adults) with diminished executive function or cognitive fragility (one healthy older subject, six with mdMCI, seven with blMCI, three with naMCI, and one with aMCI). Group 2 included 31 subjects (14 young adults, 11 older adults, six very old adults) with or without mild amnesic cognitive impairment (24 healthy subjects, two with blMCI, and five with aMCI). The subjects were grouped by motor performance, which appeared to be directly linked to their cognitive ability. However, the results showed that this task does not depend on the effects of aging (old or even very old subjects were mixed with the young subjects in group 2). Subjects in group 1 did not perform well on the WSC because their gait parameters were poor, whereas subjects in group 2 showed better walking performance on the WSC because their gait parameters were significantly better. This dual-task test was able to detect overall cognitive fragility possibly linked to normal cognitive aging or to a predementia state with a sensitivity of 71% and a specificity of 96%, and detected a change in executive function with a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 94%.

Table 2 Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants stratified by cluster results

Effect of Stroop during locomotion

We observed a significant interaction between gait parameters, conditions, and groups (F = 5.27; P < 0.001). Post hoc analysis did not reveal a significant difference between dual-task conditions for either group with regard to parameters for the number of steps, gait cycle time, or time in double support (). A significant difference was found between dual-task conditions for velocity and frequency only in group 2. These subjects were faster in condition DTcolor than in condition DTB&W (F = 5.27; P < 0.001) and in condition DTword (F = 5.27; P < 0.001, ). Frequency was also higher in condition DTcolor than in DTB&W (F = 5.27; P < 0.001) and in DTword (F = 5.27; P < 0.001, ). There was no difference between condition DTcolor and the two other conditions for these two parameters in group 1 ().

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study dealing specifically with spatiotemporal gait parameters during visuospatial dual-tasking used to detect mild cognitive impairment. The WSC provides sensitivity (89%) and specificity (94%) that is of significant interest in the early detection of predementia dysexecutive impairment.

The WSC test is a complex dual-tasking exercise because the subject must adapt his/her gait and navigate on targets while mentally inhibiting cognitive information. This cognitive function is known for being particularly sensitive to pathological aging (mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease).Citation23–Citation25 In the present study, as in other studies, adaptation of the Stroop color–word test during environmental situations appeared to provide supplementary information on the cognitive ability of subjects with mild cognitive impairment during dual-taskingCitation30 and of healthy subjects during a Stroop task in virtual reality,Citation29 when compared with traditional paper–pencil neuropsychological tests. Most studies have approached this issue by seeking to demonstrate significant differences between healthy subjects and those with mild cognitive impairment on a locomotor level during dual-tasking in predetermined groups.Citation13,Citation16,Citation43 The drawback for these types of analyses based on group comparisons is that although they reveal a link between executive function and motor ability, they do not come within the logic of detection or early detection of cognitive impairment. Conversely, with the WSC, the second cluster analysis made it possible to detect seven of nine subjects who had early-stage executive function fragility which was not detected by analysis of single-task walking or traditional paper–pencil neuropsychological tests.

Prospective studies over periods of 5 and 6 years in cohorts of 427 and 603 older subjects over 70 years of age demonstrated that initial quantitative measures of gait (velocity, variability, frequency) can predict the risk of developing cognitive impairment or dementia.Citation1,Citation2 Verghese et alCitation2 showed that, depending on modified gait parameters, one can even characterize the profile of cognitive impairment (modification of velocity and length of step are factors associated with decline in executive function, whereas the frequency factor determines mnesic deterioration). It is observed that the subjects did not differ in gait assessment in a linear manner, whereas the WSC seems to be a discriminant dual-task to separate out in the elderly those who have dysexecutive problems. On analyzing single-task gait parameters, we did not find factors predictive of cognitive decline (). It was only by using the WSC that we found two distinct motor profiles (). In addition to distinguishing themselves at a motor level, our two groups of subjects had different levels of cognitive ability. Group 1 subjects have mainly dysexecutive fragility or cognitive impairment diagnosed by paper–pencil neuropsychological tests, whereas group 2 was made up of younger and older subjects of whom only a few had impairment of mnesic function. Depending on their typology, cognitive functions were associated with subject dual-task motor abilities.

This new approach to adaptation of dual-tasking to a neuropsychological test increased the specificity for detection of dysexecutive impairment. Several authors have shown that a deficit in executive function is associated with disruption of walking as part of dual-tasking,Citation14,Citation19 and that increasing the complexity of motor tasks enables characterization of the cognitive profile of subjects.Citation14 In fact, not all subjects with mild cognitive impairment respond in the same manner to visuospatial dual-task exercises, because the motor performance of subjects with aMCI did not differ from those of healthy subjects during the WSC test or the TMT test by Persad et al.Citation14 Mnesic function did not play a significant role in motor performance in certain walking situations.Citation14,Citation44 The complexity of the WSC is based on spatial navigation abilities, visual information processing, and cognitive load (mental inhibition). In addition, this exercise causes hesitation in the elderly, which results in increased double support time and corresponds to information processing time and cognitive task performance.

The role of vision in gait control during locomotion has been demonstrated by numerous authors, particularly when the environment is enriched with visual information.Citation45–Citation47 Vision is principally used in the support phase when one must plan and execute an optimal step.Citation45 During WSC, this mechanism triggers a modification in gait parameters, in particular by a reduction in velocity and frequency, and more so by an increase in double support time. At the same time, Di Fabio et alCitation48 suggested that individuals with a reduced cognitive ability have more difficulty identifying the environment and it is necessary for them to fixate more to have a maximum of visual information. The distinction between the motor abilities of healthy (younger or older) and subjects with dementia pathology can also be explained by this strategy to favor the treatment of information during the double support phase because the attentional cost needed to control posture is low and attentional resources are more easily available to perform the cognitive task. The WSC is a complex dual-tasking exercise, the value of which is very early detection of impairment or even cognitive fragility (blMCI) by analyzing motor performance.

The notion of fragility is a recent concept that makes it possible to target a category of older subjects who are physically vulnerable. The cognitive dimension is rarely taken into account. However, these two aspects appear to be intertwined. Hommet and MondonCitation49 stressed the existence of a relationship between executive function and motor fragility. However, few studies have made the link between motor fragility reflected by a reduction in walking velocity and cognitive fragility reflected by an early alteration in executive function. Nevertheless, the WSC demonstrated that low walking velocity in dual-tasking is an element in cognitive fragility (ie, subjects with blMCI). We suggest that borderline subjects need to be monitored because their cognitive profiles suggest that they are potentially more at risk of developing mild cognitive impairment. Early detection makes it possible to prescribe a program of retraining and/or cognitive stimulation for subjects with slight cognitive decline in order to delay the appearance of new symptoms and/or aggravation of existing cognitive impairment as far as possible.

If we were to hypothesize that these blMCI are going to worsen on the cognitive level, it would mean that alteration in motor performance could occur before detection of cognitive impairment. Could analysis of walking in a dual-task environment be a biomarker of early cognitive impairment? It would be advisable to position that in relation to other concepts, such as that of cognitive reserveCitation50 and the ability to distinguish healthy aging from pathologic aging. Indeed, one can suppose that these borderline subjects have a cognitive reserve or possess compensatory mechanisms that enable them to pass cognitive paper-pencil tests, thereby masking their true decrease in intellectual performance during single-tasking. However, we know that this cognitive reserve is rapidly overwhelmed in a dual-task situation, revealing motor or cognitive fragility.Citation51,Citation52 It is difficult to make a judgment on the pre-eminence of cognitive decline over motor decline, although it is probable that cognitive deterioration, even if undiagnosed, occurs before a change in postural and locomotor patterns. Moreover, it remains difficult to distinguish between a decrease in cognitive performance linked to a pathological state and that related to normal aging, inasmuch as the evolution of mild cognitive impairment is not well understood.Citation3 Nevertheless, it would appear that our dual-task conditions contributed to the ability to distinguish between these two categories.

When one investigates human navigation and, in particular, the strategies implemented for moving about, one must also consider the role of vision in walking. The study of intraindividual variability made it possible to verify if Stroop test interference is preserved in dual-task conditions. Group 2 subjects (young, healthy elderly, or with aMCI) were more successful in DTcolor than in DTword or DTB&W, meaning that it appeared easier for these subjects to avoid reading the word than the color. These results tend to go against the Stroop color–word test, in which subjects had the most difficulty refraining from reading the word when they were asked to name the color. In order to maintain a regular walking velocity on the WSC, subjects must anticipate visualizing the targets to process the responses upstream without having to stop. On the WSC, each line has several pieces of information and requires several hesitant jerky movements to process them. We can suppose that the subjects did not have enough time during locomotion to use all of the cues necessary for reading the words. This is the reason they appeared to be less successful during the DTcolor test (interference condition in the paper–pencil version) than during the DTword or DTB&W.

In contrast, we noted no significant difference between dual-task conditions for group 1 subjects with dysexecutive syndrome, meaning that no matter what visual stimuli were used, the complexity of the dual-task was identical for all of the conditions. Interactions between the ocular and locomotor systems could explain why dual-task complexity was identical regardless of the visual stimuli used. During the TMT test, poor locomotor performance is correlated with a decrease in visual ability.Citation14 Using the Benton scale, Amieva et alCitation53 showed that alteration of visual memory occurs very early in AD. Thus, the more advanced the cognitive decline, the more the reduction in motor performance in dual-tasking is likely to be linked to a decrease in visual ability. This could also account for why there were no differences in WSC dual-task conditions in group 1. One could suppose that as soon as a subject presenting with cognitive impairment is placed in a visuospatial dual-tasking situation (regardless of the complexity of the task), they will show decreased motor performance.

From a neuroanatomical point of view, Al-Yahya et alCitation17 expressed an interest in validating dual-task models to improve our knowledge about walking ability in subjects with dementia and the neuronal mechanisms that control them. Gwin et alCitation54 performed an electroencephalogram on a subject walking on the WSC and noted activation of the anterior cingulate cortex during placement of the foot on the carpet, similar to detection of an error in placing the foot and correction of its trajectory. Moreover, performance of the Stroop test requires involvement of both the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate cortex.Citation55 During the WSC test, one could imagine that there is a conflict at the level of the anterior cingulate cortex, which simultaneously manages performance of the cognitive taskCitation55 and correct placement of the foot.Citation54 This conflict at the level of the anterior cingulate cortex could be increased in subjects with mdMCI because this cerebral zone is often prematurely deteriorated in patients with dementia.

Scherder et alCitation56 believe that one can predict a change in walking control and motor performance in subgroups of patients with dementia pathology using the concept of “last in-first out”, ie, the neuronal circuits that mature late would be the first to deteriorate in neurodegenerative pathology. Scherder et alCitation56 observed early degeneration of the anterior cingulate cortex and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in subjects with frontotemporal or vascular dementia which triggered difficulties at a motor level in coordinating complex foot movements and planning movements. Therefore, the motor performance seen in subjects with dysexecutive function from group 1 is likely to be linked to early degeneration of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortices as well as the anterior cingulate cortex, and these subjects would be susceptible to progressive dementia pathology, such as frontotemporal and vascular dementia. Cerebral imaging will be used in a future study to confirm or refute this hypothesis.

Our study has some limitations which should be taken into account. It is based on a small sample of 35 older and 14 younger subjects. Further, it did not include a “gold standard” test to confirm that all subjects with so-called mild cognitive impairment were really cognitively impaired, so it is difficult to compare our results with those of other researchers.

There are several opportunities for future research on this topic. Firstly, it would be interesting to perform these tests in a group of AD patients to determine whether they perform similarly to the patients in our group 2. Moreover, we plan to follow up our population with repeat testing every year to monitor their cognitive status and confirm the relevance of our tests in the early detection of cognitive disorders. Finally, we suspect that integrating this type of dual-tasking with training programs or physical therapy would delay cognitive and motor decline in the elderly.

Conclusion

Analysis of spatiotemporal parameters during spontaneous walking does not make it possible to qualify mild cognitive impairment. The WSC test is a good method for early detection of predementia cognitive impairment because it detects subjects with fragile executive function using motor parameters. The test is rapid and simple to perform, and the carpet is adjustable and can be set with increasing difficulty.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- WaiteLMGraysonDAPiguetOCreaseyHBennettHPBroeGAGait slowing as a predictor of incident dementia: 6-year longitudinal data from the Sydney Older Persons StudyJ Neurol Sci2005229–2308993

- VergheseJWangCLiptonRBHoltzerRXueXQuantitative gait dysfunction and risk of cognitive decline and dementiaJ Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry200778992993517237140

- GauthierSReisbergBZaudigMMild cognitive impairmentLancet200636795181262127016631882

- PetersenRCMild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entityJ Intern Med2004256318319415324362

- WinbladBPalmerKKivipeltoMMild cognitive impairment – beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive ImpairmentJ Intern Med2004256324024615324367

- ErkSSpottkeAMeisenAWagnerMWalterHJessenFEvidence of neuronal compensation during episodic memory in subjective memory impairmentArch Gen Psychiatry201168884585221810648

- SiuKCChouLSMayrUDonkelaarPWoollacottMHDoes inability to allocate attention contribute to balance constraints during gait in older adults?J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200863121364136919126850

- de BruinEDSchmidtAWalking behaviour of healthy elderly: attention should be paidBehav Brain Funct201065920939911

- WatsonNLRosanoCBoudreauRMExecutive function, memory, and gait speed decline in well-functioning older adultsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci201065101093110020581339

- Plummer-D’AmatoPAltmannLJReillyKDual-task effects of spontaneous speech and executive function on gait in aging: exaggerated effects in slow walkersGait Posture201133223323721193313

- Lundin-OlssonLNybergLGustafsonY“Stops walking when talking” as a predictor of falls in elderly peopleLancet199734990526179057736

- GillainSWarzeeELekeuFThe value of instrumental gait analysis in elderly healthy, MCI or Alzheimer’s disease subjects and a comparison with other clinical tests used in single and dual-task conditionsAnn Phys Rehabil Med200952645347419525161

- MuirSWSpeechleyMWellsJBorrieMGopaulKMontero-OdassoMGait assessment in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: the effect of dual-task challenges across the cognitive spectrumGait Posture20123519610021940172

- PersadCCJonesJLAshton-MillerJAAlexanderNBGiordaniBExecutive function and gait in older adults with cognitive impairmentJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci200863121350135519126848

- TheillNMartinMSchumacherVBridenbaughSAKressigRWSimultaneously measuring gait and cognitive performance in cognitively healthy and cognitively impaired older adults: the Basel motor-cognition dual-task paradigmJ Am Geriatr Soc20115961012101821649627

- Montero-OdassoMMuirSWSpeechleyMDual-task complexity affects gait in people with mild cognitive impairment: the interplay between gait variability, dual tasking, and risk of fallsArch Phys Med Rehabil201293229329922289240

- Al-YahyaEDawesHSmithLDennisAHowellsKCockburnJCognitive motor interference while walking: a systematic review and meta-analysisNeurosci Biobehav Rev201135371572820833198

- MiyakeAFriedmanNPEmersonMJWitzkiAHHowerterAWagerTDThe unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “Frontal Lobe” tasks: a latent variable analysisCogn Psychol20004114910010945922

- Yogev-SeligmannGHausdorffJMGiladiNThe role of executive function and attention in gaitMov Disord200823332934218058946

- AllaliGAssalFKressigRWDubostVHerrmannFRBeauchetOImpact of impaired executive function on gait stabilityDement Geriatr Cogn Disord200826436436918852489

- Montero-OdassoMCasasAHansenKTQuantitative gait analysis under dual-task in older people with mild cognitive impairment: a reliability studyJ Neuroeng Rehabil200963519772593

- FournetNMoscaCMoreaudODeficits in inhibitory processes in normal aging and patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a reviewPsychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil200754281294 French18048106

- AmievaHPhillipsLHDella SalaSHenryJDInhibitory functioning in Alzheimer’s diseaseBrain2004127Pt 594996414645147

- BellevilleSRouleauNVan der LindenMUse of the Hayling task to measure inhibition of prepotent responses in normal aging and Alzheimer’s diseaseBrain Cogn200662211311916757076

- BelangerSBellevilleSGauthierSInhibition impairments in Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment and healthy aging: effect of congruency proportion in a Stroop taskNeuropsychologia201048258159019879885

- DaultMCGeurtsACMulderTWDuysensJPostural control and cognitive task performance in healthy participants while balancing on different support-surface configurationsGait Posture200114324825511600328

- GrabinerMDTroyKLAttention demanding tasks during treadmill walking reduce step width variability in young adultsJ Neuroeng Rehabil200522516086843

- ValleeMMcFadyenBJSwaineBDoyonJCantinJFDumasDEffects of environmental demands on locomotion after traumatic brain injuryArch Phys Med Rehabil200687680681316731216

- ParsonsTDCourtneyCGArizmendiBDawsonMVirtual Reality Stroop Task for neurocognitive assessmentStud Health Technol Inform201116343343921335835

- PerrochonAKemounGWatelainEBerthozAThe “ecological Stroop test” : an innovative dual-task conceptClin Neurophysiol2011414206 French

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res19751231891981202204

- DuboisBSlachevskyALitvanIPillonBThe FAB: a Frontal Assessment Battery at bedsideNeurology200055111621162611113214

- YesavageJABrinkTLRoseTLDevelopment and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary reportJ Psychiatr Res198217137497183759

- LawtonMPBrodyEMAssessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily livingGerontologist1969931791865349366

- WechslerDWeschsler Adult Intelligence Scale-IIISan Antonio, TXThe Psychological Corporation1997

- Army Individual Test BatteryManual of Directions and ScoringWashington, DCWar Department Adjutant General’s Office1944

- StroopJRStudies of interference in serial verbal reactionsJ Exp Psychol1935186643662

- DuboisBTouchonJPortetFOussetPJVellasBMichelB“The 5 words”: a simple and sensitive test for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s diseasePresse Med2002313616961699 French12467149

- TroyerAKLeachLStraussEAging and response inhibition: Normative data for the Victoria Stroop TestNeuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn2006131203516766341

- LordSRClarkRDWebsterIWVisual acuity and contrast sensitivity in relation to falls in an elderly populationAge Ageing19912031751811853790

- WardJHHierarchical grouping to optimize an objective functionJ Am Stat Assoc196358236244

- HartiganJAClustering algorithmsProbability and Mathematical StatisticsNew York, NYJohn Wiley & Sons1975

- MaquetDLekeuFWarzeeEGait analysis in elderly adult patients with mild cognitive impairment and patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease: simple versus dual task: a preliminary reportClin Physiol Funct Imaging2010301515619799614

- HausdorffJMYogevGSpringerSSimonESGiladiNWalking is more like catching than tapping: gait in the elderly as a complex cognitive taskExp Brain Res2005164454154815864565

- HollandsMAMarple-HorvatDEVisually guided stepping under conditions of step cycle-related denial of visual informationExp Brain Res199610923433568738381

- ChapmanGJHollandsMAEvidence for a link between changes to gaze behaviour and risk of falling in older adults during adaptive locomotionGait Posture200624328829416289922

- ChapmanGJHollandsMAEvidence that older adult fallers prioritise the planning of future stepping actions over the accurate execution of ongoing steps during complex locomotor tasksGait Posture2007261596716939711

- Di FabioRPZampieriCHenkeJOlsonKRickheimDRussellMInfluence of elderly executive cognitive function on attention in the lower visual field during step initiationGerontology20055129410715711076

- HommetCMondonKBBTCIs alteration of executive functions a factor for frailty in the elderly subject?Ann Gerontol201033175180

- SternYCognitive reserveNeuropsychologia200947102015202819467352

- BhererLKramerAFPetersonMSColcombeSEricksonKBecicETesting the limits of cognitive plasticity in older adults: application to attentional controlActa Psychol (Amst)2006123326127816574049

- VergheseJMahoneyJAmbroseAFWangCHoltzerREffect of cognitive remediation on gait in sedentary seniorsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci201065121338134320643703

- AmievaHLe GoffMMilletXProdromal Alzheimer’s disease: successive emergence of the clinical symptomsAnn Neurol200864549249819067364

- GwinJTGramannKMakeigSFerrisDPElectrocortical activity is coupled to gait cycle phase during treadmill walkingNeuroimage20115421289129620832484

- CarterCSvan VeenVAnterior cingulate cortex and conflict detection: an update of theory and dataCogn Affect Behav Neurosci20077436737918189010

- ScherderEEggermontLVisscherCScheltensPSwaabDUnderstanding higher level gait disturbances in mild dementia in order to improve rehabilitation: ‘last in-first out’Neurosci Biobehav Rev201135369971420833200