Abstract

Background

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is the most prevalent medical condition in individuals over the age of 65 years, and is a progressive joint degenerative condition with no known cure. Research suggests that there is a strong relationship between knee pain and loss of physical function. The resulting lifestyle modifications negatively impact not only disease onset and progression but also overall health, work productivity, and quality of life of the affected individual.

Purpose

The goal of this investigation was to examine the feasibility of using an emerging technology called lower body positive pressure (LBPP) to simulate weight loss and reduce acute knee pain during treadmill walking exercise in overweight individuals with radiographically confirmed symptomatic knee OA.

Design

Prospective case series.

Methods

Twenty-two overweight individuals with knee OA completed two 20-minute treadmill walking sessions (one full weight bearing and one LBPP supported) at a speed of 3.1 mph, 0% incline. Acute knee pain was assessed using a visual analog scale, and the percentage of LBPP support required to minimize knee pain was evaluated every 5 minutes. Knee Osteoarthritis Outcome Scores were used to quantify knee pain and functional status between walking sessions. The order of testing was randomized, with sessions occurring a minimum of 1 week apart.

Results

A mean LBPP of 12.4% of body weight provided participants with significant pain relief during walking, and prevented exacerbation of acute knee pain over the duration of the 20-minute exercise session. Patients felt safe and confident walking with LBPP support on the treadmill, and demonstrated no change in Knee Osteoarthritis Outcome Scores over the duration of the investigation.

Conclusion

Results suggest that LBPP technology can be used safely and effectively to simulate weight loss and reduce acute knee pain during weight-bearing exercise in an overweight knee OA patient population. These results could have important implications for the development of future treatment strategies used in the management of at-risk patients with progressive knee OA.

What is known about the subject?

This investigation is the first to examine the feasibility of using a new and emerging technology called lower body positive pressure (LBPP) to support low-load treadmill walking exercise in an at-risk knee osteoarthritis (OA) patient population.

What this study adds to the existing knowledge

LBPP is an emerging unweighting technology that can be used safely and successfully to simulate weight loss and study low-load weight-bearing exercise in overweight patients with progressive knee OA. LBPP support of only 12.4% body weight was required to manage and prevent exacerbation of acute knee pain symptoms during treadmill walking exercise.

Introduction

Knee OA is the most common form of arthritis,Citation1 currently affecting more than 25 million North Americans, with the incidence expected to double by the year 2020.Citation1,Citation2 In fact, the current rate of knee OA is as high as that of cardiac disease, and it is the most prevalent medical condition in individuals aged over 65 years.Citation3 It is a joint pathology characterized by the formation of osteophytes and cysts, narrowed joint spacing, and subchondral bone sclerosis.Citation4 Although the age of onset and symptoms related to joint degeneration can vary greatly from patient to patient, disease progression is commonly associated with progressive and debilitating joint pain, stiffness, muscle weakness, and decreased joint range of motion. These signs and symptoms make it difficult to perform essential activities of daily living such as walking, squatting, and going up and down stairs.Citation5 Implications of disease progression include restrictions in daily activities, reduced work productivity, and diminished quality of life.Citation2,Citation6

At present, there is no known cure.Citation7 Current approaches to nonoperative treatment primarily focus on the management of symptoms through the use of pharmacological interventions (such as analgesic and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications) that are designed to target joint pain and swelling associated with disease progression, or through nutritional supplementation (such as chondroitin and glucosamine) that is postulated to improve articular cartilage health.Citation8 Unfortunately, these passive forms of intervention do very little to address underlying risk factors (such as obesity, abnormal joint kinematics due to injury, thigh muscle weakness, and leg misalignment) that have been clearly identified within the OA literature as having a direct impact on the age of onset and rate of disease progression,Citation9 and in many instances may actually place the patient at significant risk for the development of other comorbidities (eg, gastrointestinal bleeding and renal and cardiac disease).Citation10,Citation11

Of the identified risk factors, being overweight (body mass index [BMI] >25 kg/m2)Citation12–Citation14 is believed to be the number one modifiable risk factor for the development and progression of knee OA.Citation1 Multiple studies have demonstrated that high body weight precedes the development of knee OA,Citation15,Citation16 influences the age of onset and rate of disease progression,Citation17–Citation19 quadruples the risk of developing knee OA for both genders,Citation20 and increases the risk for developing OA in the contralateral knee.Citation1,Citation21 Research examining the relationship between weight loss and joint function in a knee OA patient population illustrates that even small amounts of weight loss (as little as 5% over an 18-month period in overweight patients) can lead to an improvement in subjective reporting of joint pain and function.Citation22 To date, researchers have been unable to quantify the strength of the relationship between loss of body weight and change in knee joint symptomsCitation23 (ie, is it a linear relationship?), little information is available to guide individualized prescription of weight loss for the management of joint pain and dysfunction, and the specific impact that weight loss has on knee joint kinematics during walking within a knee OA patient population is unknown.

Knee OA research also illustrates that weight-bearing exercise such as a daily walking regimen is effective for managing joint symptoms, enhancing functional capacity and quality of life, and decreasing patient reliance on analgesic medication.Citation5,Citation24 As a result, regular exercise is a recommended treatment strategy by both the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism.Citation8,Citation25 When one considers that a force of roughly three to six times body weight is exerted across a healthy knee joint during the single stance phase of walking, it becomes clear that an overweight or obese person with knee OA is at significant risk for exacerbation of joint symptoms and disease progression when initiating a regular weight-bearing walking program.Citation26

Recently, a new treadmill (G-Trainer® treadmill by AlterG Inc, Fremont, CA, USA) () was introduced that permits low-load walking using an emerging technology called LBPP.Citation27 The system utilizes a waist-high air chamber that can be inflated with positive air pressure in order to modify body weight during ambulation. During an exercise session, subjects wear a pair of neoprene shorts with a kayak-style skirt that zips into an air chamber, creating an airtight seal. When the air chamber inflates, there is an increase in air pressure around the lower body that lifts the subject upwards at the hips.Citation27,Citation28 This effectively reduces body weight and the gravitational forces about the lower extremity to a level that can be adjusted with a high degree of consistency.Citation28,Citation29 Positive air pressure can then be used to accurately unweight a person by increments as small as 1% body weight and as large as 80% body weight.Citation30 LBPP is recognized as being superior to other methods of unweighting (such as an upper body harness that partially supports body weight, or aquatic exercises), because the air pressure is applied uniformly over the lower body, thus reducing the formation of pressure points that are common with harness-based systems,Citation31,Citation32 while maintaining normal muscle activation and gait patterns (which are altered during aquatic-based activities).Citation28,Citation33,Citation34 As a result, the LBPP treadmill technology is gaining popularity as a device that offers the ability to study weight-supported or low-load exercise in a user-friendly and kinematically correct manner,Citation28,Citation35 without altering gait dynamicsCitation28 or cardiovascular parameters such as heart rate and blood pressure.Citation29,Citation36 LBPP trials have so far been reported on several musculoskeletal conditions, including meniscectomy and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction,Citation27 as well as lower limb trauma.Citation37 Each of these studies used LBPP to create a low-load exercise regime that essentially permitted patients to resume early and/or pain-free ambulation, or to walk further and for longer periods than was previously possible during normal walking (ie, during full weight bearing [FWB]) without exacerbation of symptoms. These reports suggest LBPP may hold promise as a method of providing a remediated weight-bearing exercise regimen for those with progressive knee OA or those at risk for developing or exacerbating knee OA symptoms due to obesity that precludes normal exercise activities. To date, the use of this emerging technology with an overweight knee OA patient population has gone unreported within the literature, and the feasibility of utilizing the LBPP technology to artificially simulate weight loss and facilitate pain-free ambulatory exercise in this patient population is unknown.

Purpose of the study

The purpose of this study was to investigate the feasibility of using LBPP support to simulate weight loss and manage acute knee pain during treadmill walking exercise in overweight individuals with radiographically confirmed symptomatic knee OA. The hypothesis was that LBPP support would significantly reduce acute knee pain during treadmill walking exercise in overweight knee OA patients.

Methods

Setting and participants

Following ethics board review and approval by the local regional health authority, 22 overweight participants (BMI >25 kg/m2) between the ages of 35 and 60 years, with radiographically confirmed symptomatic mild to moderate knee OA were recruited to participate in the study. Each participant was assigned an identification number and required to complete informed consent, personal information, and knee demographic forms prior to initiation of participation in the study. The knee demographic form provided a detailed history of the patients’ knee OA, such as previous history of injury or surgery, and previous and current treatment methods, such as bracing, injections, and pharmacological intervention. In addition, the form was also used to confirm knee symptoms, knee function, and activities that initiate knee pain symptoms, as well as to provide information relevant to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Participants were excluded if they had a recent history of traumatic hip, knee, or ankle surgery (within the last year), had severe knee OA, or were diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, chronic reactive arthritis, or psoriatic arthritis. Anteroposterior radiographs were taken for all subjects in a weight-bearing position with both knees in 5° of flexion. Each radiograph was reviewed by a senior radiologist specializing in musculoskeletal imaging, and scored using the Kellgren–Lawrence scale,Citation38 with subjects who scored 0 (indicating no signs of OA) and 4 (indicating severe OA) being excluded from participation.Citation1,Citation8 Participants also completed a short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity (SQUASH questionnaire),Citation39 and anthropometric measurements such as height and weight were taken prior to the first treadmill walking session and then used to calculate BMI. All participants were directed to wear shorts and T-shirts for their assessment, and asked to refrain from exercise a minimum of 4 hours prior to each of their data collection sessions.

Treadmill walking sessions

All participants completed two G-Trainer treadmill walking sessions during the course of the study, one FWB walking session and one LBPP-supported walking session, which occurred a minimum of 7 days apart. The study utilized a methodology that randomized the order of treadmill testing (FWB or LBPP supported), visually blinded subjects to the percentage of LBPP support utilized during each walking session, and ensured that the LBPP blower and air chamber were on and pressurized even when participants were performing the FWB treadmill walking sessions with 0% LBPP support. Prior to each walking session (as well as 1 week after completing the second walking session), participants completed a Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) questionnaire to quantify knee pain and function over the previous 7-day period. Scoring on the KOOS can range from 0 (complete disability) to 100 (no disability) and is evaluated using five categories: (1) pain, (2) symptoms, (3) function in daily living, (4) sports/recreation, and (5) quality of life.Citation40,Citation41 For all treadmill walking sessions, participants were required to walk at a speed of 1.4 m/s (3.1 mph) at 0° incline for a period of 20 minutes.

Each participant completed an initial 5-minute warm-up on the treadmill prior to the initiation of data collection. This allowed subjects to gradually reach the predetermined walking speed (3.1 mph at 0° incline) and adjust to walking on the treadmill’s belt surface. For the FWB walking sessions, no LBPP support was applied (but the LBPP blower and air chamber were on and the chamber pressurized). For the LBPP-supported walking sessions, the goal was to select a percentage of unweighting that completely eliminated or substantially reduced the participants’ acute knee pain during treadmill walking. LBPP pressure was constantly monitored and systematically adjusted by 5% increments (up to a maximum of 30% LBPP support) to maintain a pain-free walking experience. Visual analog scale (VAS) acute knee pain measures were taken at 5-minute intervals during each treadmill walking session, with the four VAS measures (at minutes 5, 10, 15, and 20) for each walking session averaged in order to obtain an overall “acute knee pain score” for that specific walking session. Participants were blinded to their KOOS and VAS scores from the previous walking session.

Data analysis

Microsoft Office Excel 2007 with Data Analysis ToolPak add-in (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond WA, USA) and SPSS Version 17 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) were used for data analysis. The sample size selected for the study was based on a VAS minimum clinically significant difference of 13/100 mm, with a standard deviation (SD) of 19 mm.Citation15 Using an α=0.05 (two-tailed) and 90% power level, a total of 23 participants were required for the study (N=22). Repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare KOOS between sessions 1 and 2 and 1 week postwalking, consecutive VAS knee pain measures taken at 5-minute intervals during either FWB or LBPP-supported treadmill walking sessions, and total (or cumulative) VA S acute knee pain scores between FWB and LBPP-supported treadmill walking during the entire 20-minute walking sessions. t-tests were used to compare VAS acute knee pain scores between FWB and LBPP-supported walking at each 5-minute interval during the treadmill walking sessions. Differences were considered statistically significant if P<0.05.

Results

Descriptive data for study participants are summarized in . Mean (± SD) age and BMI of the 22 participants (17 female; five male) were 52.9 (±5.9) years and 33.6 (±6.4) kg/m2, respectively. Knee demographic data illustrated that eleven of the 22 participants had a history of traumatic knee injury, with the average duration of OA symptoms being 147 (±185) months among the group. Nine of 22 participants demonstrated bilateral knee OA, with data for the more painful knee being used for statistical analysis. All participants, except one, exhibited medial knee compartment degeneration on radiograph (one exhibited lateral compartment degeneration). Data from the SQUASH physical activity questionnaire indicated that study participants reported high levels of physical activity, spending an average of 9.1 hours per week in physical activity, of which 15.5% was classified as moderately intense activity and 11.9% was high-intensity activity.

Table 1 Descriptive information for the sample patient populationTable Footnotea

LBPP-supported walking session data are presented in . On average, approximately 12.4% (±7.4%) of LBPP support was required in order to minimize participants’ knee pain during the LBPP-supported walking session, with 15% of LBPP support being the median amount of unweighting required to minimize or eliminate acute knee pain over the duration of the 20-minute walking session, and the maximum LBPP support ranging from 5% to 30% of total body weight among participants.

Table 2 Percentage of support required to minimize acute knee pain during lower body positive pressure (LBPP)-supported walking

VAS knee pain data collected at 5-minute intervals during both 20-minute walking sessions (FWB and LBPP supported) are summarized in . VAS scoring for knee pain during the LBPP walking session was consistently lower than VAS scoring for the FWB walking session at each 5-minute interval (however, these differences were not statistically different), with the size of the difference in pain scores increasing as the duration of the walking session became longer. However, repeated-measures ANOVA testing revealed a statistically significant difference (P<0.05) only when comparing the total (or cumulative) “acute knee pain score” from all VAS measurements (ie, average of VAS measures taken at minutes 5, 10, 15, and 20) taken during each LBPP and FWB 20-minute walking session.

Table 3 Acute knee pain during walkingTable Footnotea

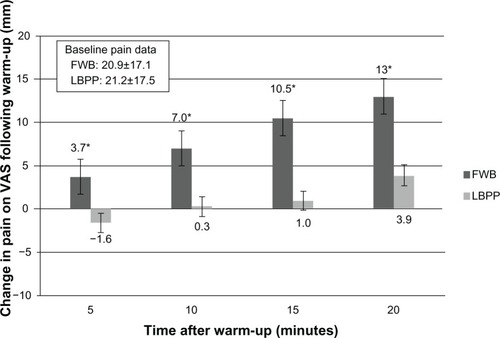

further illustrates the cumulative treatment effect associated with LBPP-supported walking. Baseline (mean ± SD) VAS pain scores for LBPP and FWB walking sessions were 21.2±17.5 and 20.9±17.1, respectively. Over the course of the 20-minute walking session, VAS pain levels for the LBPP-supported walking sessions initially dropped and then increased only marginally. In comparison, VAS pain levels for the FWB walking session steadily increased over the duration of the 20-minute walking session. The knee pain experienced during FWB walking increased significantly between the first pain data point (at the 5-minute interval) and the last pain data collection point (at the 20-minute interval) (P=0.002), with pain increases at each 5-minute interval being statistically significant. Importantly, knee pain did not significantly increase over the entire duration of the LBPP-supported treadmill walking sessions (P=0.58) or between any of the individual 5-minute intervals.

Figure 2 Change in knee pain during walking.a

Knee function as measured on the KOOS is summarized in . Response rates for the first two surveys were 100%, and 65.0% for the last survey. Missing data from individual sections of the KOOS were calculated using methods previously described in the literature.Citation41 Briefly, if scoring on one or two questions was missing in a specific subsection, the average for that subsection was substituted as the score for that specific question. If more than two values were missing, the subscale score was considered invalid and was not calculated. There were no cases of more than two values missing per subscale. Analysis via repeated-measures ANOVA indicated that KOOS scoring remained constant throughout participants’ involvement in the study, with no significant differences being noted when comparing the results of the first, second and third survey.

Table 4 Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) scoringTable Footnotea

Discussion

To our knowledge, this investigation is the first to examine the feasibility of using a new and emerging technology called LBPP to support low-load treadmill walking exercise in an at-risk knee OA patient population. The results suggest that LBPP support can be utilized safely and successfully to simulate weight loss and manage acute knee pain during prolonged walking exercise. LBPP support of only 12.4% body weight was required to significantly diminish knee pain in overweight knee OA patients. These results could have important implications for the development of future treatment strategies used in management of joint pain and dysfunction associated with the progressive knee OA in at-risk patients.

The individuals who participated in this investigation were representative of a young (age range 36–64 years) and overweight (range 25–47 kg/m2) patient population with early-onset knee OA. Patients reported experiencing progressive symptoms of joint pain, stiffness, muscle weakness, and decreased joint range of motion for more than 10 years (on average), with radiographic evaluation of the affected joint revealing the presence of joint space narrowing and osteophyte formation for all participants. KOOS for knee pain and function were consistent over the duration of the investigation and comparable with previous reports examining a knee OA patient population. Interestingly, physical activity data (from the SQUASH survey) revealed that although individuals still participated in activities that would be classified as “moderate or vigorous physical activity,” such as sporting and recreational activities (ie, activities requiring energy expenditures greater than four metabolic equivalents), KOOS scoring suggested that they experienced significant difficulties during these types of participation, and that this had a negative impact on their overall quality of life scores. This finding may be reflective of the fact that the study sample was representative of a young knee OA demographic who still regularly participated in sporting and recreational activities despite the risk of further exacerbation of knee pain and joint symptoms. Although OA is often thought of as a disease of the elderly, the incidence of this degenerative condition at younger ages is becoming more prevalent, with approximately 5% of the population aged 35–54 years presenting with radiographic signs of knee OA.Citation42 Research demonstrates that adolescents and young adults with a history of traumatic joint injury, especially at the knee, are at greater than five-fold increased risk for the development of future OA.Citation43–Citation46

Of the identified risk factors, being overweight (BMI of >25 kg/m2) is considered to be the number one modifiable risk factor for the development and progression of knee OA, with research suggesting that each 1 lb (0.45 kg) of weight gain results in a corresponding 4 lb (1.81 kg) increase in knee joint loads during walking.Citation47 If high body weight results in an increased risk in the onset and progression of knee OA, then decreasing body weight may have preventive effects. In the current study, an emerging technology called LBPP was successfully used to simulate weight loss and diminish acute knee joint pain and permit low-load walking exercise in a young overweight knee OA patient population. Data indicated that an average LBPP support of only 12.4% (±7.4%) of body weight resulted in a significant decrease in a participant’s acute knee pain while treadmill walking for 20 minutes. This finding is significant for several reasons.

First, our study confirms the findings of previous investigations that have indicated that LPBB-supported exercise interventions are a safe and user-friendly method of remediating weight-bearing exercise.Citation37 Previous reports have examined the use of the LBPP technology in the rehabilitation of young and otherwise healthy, physically active patients who have sustained acute musculoskeletal injuries.Citation27,Citation37 Each of these investigations utilized the LBPP technology as a method to successfully remediate or accelerate a progressive rehabilitation protocol, with the level of LBPP support, walking speed, and/or incline being adjusted as the patient progressed through their rehabilitation. Our investigation is the first to examine the feasibility of LBPP support in the management of a chronic or degenerative musculoskeletal condition, utilizing a standardized methodological approach (ie, 5-minute warm-up, 20 minutes of treadmill walking at 3.1 mph, 0% incline, 60%–80% maximal heart rate). All participants were able to complete the prescribed treadmill protocol under both the FWB and LBPP-supported walking conditions, with no participants withdrawing from the study. The consistency of KOOS data suggests that participants did not experience any exacerbation of joint symptoms over the duration of the investigation, that LBPP pressure was well tolerated, and that the prescribed walking protocol facilitated safe and user-friendly weight-bearing exercise.

Second, to our knowledge, this investigation represents the first published report on the feasibility of utilizing the LBPP technology to simulate weight loss and control acute knee pain in an overweight knee OA patient population during walking exercise. Results indicate that LBPP support can be used to significantly control acute knee pain during treadmill walking, and unlike FWB walking, LBPP-supported walking did not result in a progressive and significant increase in acute pain symptoms over the duration of a 20-minute treadmill walk. This suggests that the LBPP technology may hold promise as a rehabilitative tool that can be utilized to successfully remediate weight-bearing exercise intervention strategies commonly used in the treatment of lower-extremity pathologies such as knee OA.

Finally, and possibly most importantly, the LBPP technology allowed for patient-specific feedback regarding acute knee pain to determine the percentage of unweighting required to manage acute knee pain during prolonged walking exercise. Anecdotally, patients commented that the LBPP support allowed them to walk pain free for the first time in years, and others indicated that they were surprised about the positive impact that air support could have on their knee pain symptoms. This approach facilitated more accuracy in the treatment intervention, and allowed the relationship between body weight and acute knee pain to be quantified in a patient-specific manner. The results indicated that the percentage of LBPP support required to minimize or eliminate knee pain during weight-bearing exercise was representative of a realistic and attainable level of weight loss for an overweight person with progressive knee OA. Prior to this investigation, no information was available regarding the percentage of LBPP required to attenuate joint pain in an overweight knee OA patient population during a steady-state exercise condition. When placed in a body weight context, the mean percentage of LBPP support required to manage acute knee pain during walking simulated a decrease in participants’ body weight of 11.6 kg (mean body weight of 93.7 kg ×12.4%=11.6 kg), thus representing a reduction of participants’ average BMI from 33.6 kg/m2 (which placed them in the categorization of obese) to 29.4 kg/m2 (reducing their categorization to overweight).

There are several limitations to the current study. This study utilized two isolated treadmill walking sessions to examine the feasibility of using LBPP support to simulate weight loss and enable pain-free low-load walking exercise in overweight knee OA patients. The efficacy of LBPP support for the modulation of knee pain in a chronic exercise/rehabilitation setting is still unknown, and caution should be used when interpreting these results as they relate to the design of future exercise interventions targeting a knee OA population. Instead, further long-term research is needed to clarify the role that this emerging unweighting technology could play in the management of joint symptoms associated with progressive knee OA in an overweight patient population. This investigation also utilized a within-subject design to look at changes in knee pain and function, with the FWB walking session serving as the control condition. There was no healthy control group used to compare changes in knee pain and function. Beyond this, concerns about how a patient’s physical perception of LBPP support (ie, the air pressure) may confound VAS scoring of knee pain are valid (ie, a patient who perceives higher LBPP support may score their acute knee pain during walking lower on the VAS scale).

Finally, the question of whether this type of exercise intervention is cost-effective or superior to other methods of low-impact, non-weight-bearing exercise warrants further investigation. Although there is some evidence to suggest that task-specific activities such as walking are superior to other non-weight-bearing activities such as strength training, cycling, and aquatic exerciseCitation5,Citation26,Citation48 (because of its ability to promote and/ r restore normal muscle strength, joint proprioception, and the joint range of motion necessary to effectively perform typical activities of daily living), research examining exercise regimens used in the management of knee OA has led to only general exercise recommendations or guidelines, with little evidence available to support the efficacy of patient or symptom-specific manipulation of the exercise regimen being prescribed.Citation8,Citation49,Citation50 Beyond this, although some investigations have attempted to compare the impact of different forms of exercise on knee pain and function in a knee OA population,Citation26,Citation50,Citation51 research comparing the treatment/cost efficacy of these different forms of exercise is currently lacking.

Conclusion

The purpose of this investigation was to examine the feasibility of using an emerging technology called LBPP to simulate weight loss and manage acute knee pain during treadmill walking exercise in overweight individuals with radiographically confirmed symptomatic knee OA. Results suggest that this unweighting technology can be used safely and successfully to simulate weight loss in a symptom-specific manner, and that LBPP support of only 12.4% body weight is required to prevent exacerbation and manage acute knee pain during prolonged treadmill walking exercise. Future research should be directed at exploring how LBPP-supported low-load exercise can be utilized to enhance the functional capacity of knee OA patients, promote physical activity levels and long-term exercise adherence, and slow disease progression in a knee OA patient population.

Ethics approval

This investigation received university ethics board approval and was authorized by the local regional health authority.

Acknowledgments

Operating funds for this research were provided by the Dr Paul HT Thorlakson Foundation and a graduate fellowship (to JT) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Ongoing research support was provided by both the Pan Am Clinic Foundation and the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Manitoba, Canada.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflict of interest to report, and received no financial aid from the equipment manufacturer. We certify that no party having a direct interest in the results of this investigation has or will confer a benefit on us or on any organization with which we are associated.

References

- ArdenNNevittMCOsteoarthritis: epidemiologyBest Pract Res Clin Rheumatol200620132516483904

- JinksCJordanKCroftPOsteoarthritis as a public health problem: the impact of developing knee pain on physical function in adults living in the community: (KNEST 3)Rheumatology (Oxford)200746587788117308312

- GuccioneAAFelsonDTAndersonJJThe effects of specific medical conditions on the functional limitations of elders in the Framingham StudyAm J Public Health19948433513588129049

- LuytenFPDentiMFilardoGKonEEngebretsenLDefinition and classification of early osteoarthritis of the kneeKnee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc201220340140622068268

- EvcikDSonelBEffectiveness of a home-based exercise therapy and walking program on osteoarthritis of the kneeRheumatol Int200222310310612111084

- LaslettLLQuinnSJWinzenbergTMSandersonKCicuttiniFJonesGA prospective study of the impact of musculoskeletal pain and radiographic osteoarthritis on health related quality of life in community dwelling older peopleBMC Musculoskelet Disord20121316822954354

- RogersMWWilderFVThe association of BMI and knee pain among persons with radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional studyBMC Musculoskelet Disord2008916319077272

- ZhangWMoskowitzRWNukiGOARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelinesOsteoarthritis Cartilage200816213716218279766

- ShraderMWDraganichLFPottengerLAPiotrowskiGAEffects of knee pain relief in osteoarthritis on gait and stair-steppingClin Orthop Relat Res200442118819315123946

- LosinaEWalenskyRPReichmannWMImpact of obesity and knee osteoarthritis on morbidity and mortality in older AmericansAnn Intern Med2011154421722621320937

- DenisovLNNasonovaVAKoreshkovGGKashevarovaNGRole of obesity in the development of osteoarthrosis and concomitant diseasesTer Arkh201082103437 Russian.21341461

- HopmanWMBergerCJosephLThe association between body mass index and health-related quality of life: data from CaMos, a stratified population studyQual Life Res200716101595160317957495

- Health CanadaCanadian guidelines for body weight classification in adultsOttawa, CanadaHealth Canada Publications Centre2003 Report No: 4645.

- World Health OrganizationObesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation on ObesityGeneva, SwitzerlandWorld Health Organization2000

- NiuJZhangYQTornerJIs obesity a risk factor for progressive radiographic knee osteoarthritis?Arthritis Rheum200961332933519248122

- WangYWlukaAESimpsonJABody weight at early and middle adulthood, weight gain and persistent overweight from early adulthood are predictors of the risk of total knee and hip replacement for osteoarthritisRheumatology (Oxford)20135261033104123362222

- BlagojevicMJinksCJefferyAJordanKPRisk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysisOsteoarthritis Cartilage2010181243319751691

- SharmaLKapoorDIssaSEpidemiology of osteoarthritis: an updateCurr Opin Rheumatol200618214715616462520

- ZhangYJordanJMEpidemiology of osteoarthritisRheum Dis Clin North Am200834351552918687270

- AckermanINOsborneRHObesity and increased burden of hip and knee joint disease in Australia: results from a national surveyBMC Musculoskelet Disord20121325423253742

- SegalNAYackHJKholePWeight, rather than obesity distribution, explains peak external knee adduction moment during level gaitAm J Phys Med Rehabil200988318018819847127

- ChristensenRBartelsEMAstrupABliddalHEffect of weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysisAnn Rheum Dis200766443343917204567

- SridharMSJarrettCDXerogeanesJWLabibSAObesity and symptomatic osteoarthritis of the kneeJ Bone Joint Surg Br201294443344022434455

- TalbotLAGainesJMHuynhTNMetterEJA home-based pedometer-driven walking program to increase physical activity in older adults with osteoarthritis of the knee: a preliminary studyJ Am Geriatr Soc200351338739212588583

- FernandesLHagenKBBijlsmaJWEULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritisAnn Rheum Dis20137271125113523595142

- PenninxBWMessierSPRejeskiWJPhysical exercise and the prevention of disability in activities of daily living in older persons with osteoarthritisArch Intern Med2001161192309231611606146

- EastlackRKHargensARGroppoERSteinbachGCWhiteKKPedowitzRALower body positive-pressure exercise after knee surgeryClin Orthop Relat Res200543121321915685078

- QuigleyEJNohHGroppoERGait mechanics using a lower body positive pressure chamber for orthopaedic rehabilitationTrans Orthop Res Soc200025828

- HargensACutukAWhiteKCardiovascular impact of lower body positive pressureMed Sci Sports Exerc1999311S

- CutukAGroppoERQuigleyEJWhiteKWPedowitzRAHargensARAmbulation in simulated fractional gravity using lower body positive pressure: cardiovascular safety and gait analysesJ Appl Physiol2006101377177716777997

- KurzMJCorrBStubergWVolkmanKGSmithNEvaluation of lower body positive pressure supported treadmill training for children with cerebral palsyPediatr Phys Ther201123323223921829114

- RuckstuhlHKhoJWeedMWilkinsonMWHargensARComparing two devices of suspended treadmill walking by varying body unloading and Froude numberGait Posture200930444645119674901

- GrabowskiAMKramREffects of velocity and weight support on ground reaction forces and metabolic power during runningJ Appl Biomech200824328829718843159

- LiebenbergJScharfJForrestDDufekJSMasumotoKMercerJADetermination of muscle activity during running at reduced body weightJ Sports Sci201129220721421170806

- PatilSSteklovNBugbeeWDGoldbergTColwellCWJrD’LimaDDAnti-gravity treadmills are effective in reducing knee forcesJ Orthop Res201331567267923239580

- GojanovicBCuttiPShultzRMathesonGOMaximal physiological parameters during partial body-weight support treadmill testingMed Sci Sports Exerc201244101935194122543742

- TakacsJLeiterJRPeelerJDNovel application of lower body positive-pressure in the rehabilitation of an individual with multiple lower extremity fracturesJ Rehabil Med201143765365621584484

- KellgrenJHLawrenceJSRadiological assessment of osteo-arthrosisAnn Rheum Dis195716449450213498604

- Wendel-VosGCSchuitAJSarisWHKromhoutDReproducibility and relative validity of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activityJ Clin Epidemiol200356121163116914680666

- RoosEMLohmanderLSThe Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritisHealth Qual Life Outcomes200316414613558

- RoosEMRoosHPLohmanderLSEkdahlCBeynnonBDKnee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): development of a self-administered outcome measureJ Orthop Sports Phys Ther199828288969699158

- RoosEMJoint injury causes knee osteoarthritis in young adultsCurr Opin Rheumatol200517219520015711235

- GelberACHochbergMCMeadLAWangNYWigleyFMKlagMJJoint injury in young adults and risk for subsequent knee and hip osteoarthritisAnn Intern Med2000133532132810979876

- NeumanPEnglundMKostogiannisIFridenTRoosHDahlbergLEPrevalence of tibiofemoral osteoarthritis 15 years after nonoperative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injury: a prospective cohort studyAm J Sports Med20083691717172518483197

- LouboutinHDebargeRRichouJOsteoarthritis in patients with anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a review of risk factorsKnee200916423924419097796

- LohmanderLSEnglundPMDahlLLRoosEMThe long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: osteoarthritisAm J Sports Med200735101756176917761605

- BrowningRCKramREffects of obesity on the biomechanics of walking at different speedsMed Sci Sports Exerc20073991632164117805097

- MessierSPLoeserRFMillerGDExercise and dietary weight loss in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: the Arthritis, Diet, and Activity Promotion TrialArthritis Rheum20045051501151015146420

- AltmanRDHochbergMMoskowitzRWSchnitzerTJRecommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and kneeArthritis Rheum20004391905191511014340

- PellandLBrosseauLWellsGEfficacy of strengthening exercises for osteoarthritis (part I): a meta-analysisPhysical Therapy Reviews20049277108

- RoddyEZhangWDohertyMAerobic walking or strengthening exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee? A systematic reviewAnn Rheum Dis200564454454815769914