Abstract

Background

Staff who provide support services to older adults are in a unique position to detect depression and offer a referral for mental health treatment. Yet integrating mental health screening and recommendations into aging services requires staff learn new skills to integrate mental health and overcome client barriers to accepting mental health referrals. This paper describes client rates of depression and a novel engagement intervention (Open Door) for homebound older adults who are eligible for home delivered meals and screened for depression by in-home aging service programs.

Methods

Homebound older adults receiving meal service who endorsed depressive symptoms were interviewed to assess depression severity and rates of suicidal ideation. Open Door is a brief psychosocial intervention to improve engagement in mental health treatment by collaboratively addressing the individual level barriers to care. The intervention targets stigma, misconceptions about depression, and fears about treatment, and is designed to fit within the roles and responsibilities of aging service staff.

Results

Among 137 meal recipients who had symptoms when screened for depression as part of routine home meal service assessments, half (51%) had Major Depressive Disorder and 13% met criteria for minor depression on the SCID. Suicidal ideation was reported by 29% of the sample, with the highest rates of suicidal ideation (47%) among the subgroup of individuals with Major Depressive Disorder.

Conclusion

Individuals who endorse depressive symptoms during screening are likely to have clinically significant depression and need mental health treatment. The Open Door intervention offers a strategy to overcome barriers to mental health treatment engagement and to improve the odds of quality care for depression.

Introduction

Initiatives implemented by aging service agencies to screen older adults for depression and other mental health or substance abuse problems are an important first step to reduce unmet need for mental health services.Citation1,Citation2 However, the success of screening in improving the link to mental health services rests largely on a successful referral process. To accept a referral and engage in mental health treatment may entail striking a balance between perceived need, the social costs of mental health care (eg, stigma, personal rejection), negative attitudes towards depression and its treatment, and overcoming tangible access obstacles.Citation3,Citation4 Many depressed older adults identified in aging services are willing to use mental health treatment,Citation5 but making an effective referral that results in treatment engagement is a skill.

In older adults, depression is associated with the risk of deterioration of cognition and medical status,Citation6 increased disability,Citation7,Citation8 increased risk of falls,Citation9 and compromised quality of life.Citation7,Citation10 Mental illness among older adults is also associated with excess utilization of health care, increased placement in nursing homes, greater burden to medical care providers, and higher annual health care costs.Citation11–Citation15 Depression in particular worsens the outcomes of many medical disorders and increases the risk for falls,Citation16 suicideCitation17 and non-suicide mortality.Citation18–Citation21 Mental health and behavioral disorders are the second leading cause of disability worldwide among non-communicable diseases.Citation22 Of these disorders, unipolar depressive disorders have the highest burden in disability-adjusted life years, and it is estimated that this burden will continue to increase. Rates of depression are increased in samples of community-dwelling older persons with greater medical illness or disability.Citation23

The level of unmet mental health need is high in older adults. A recent analysis of older adults in the National Comorbidity Study Replication sample found that 70% of older adults with mood and anxiety disorders did not receive mental health treatment.Citation24 In a 9-year community follow-up study of older adults with depressive symptoms, 43%–69% did not receive treatment for depression during any 18-month interval. In addition, 31% of the 121 participants with persistent depression did not receive mental health treatment during the study period.Citation25

Home-based agency services offer a unique opportunity to address unmet mental health needs in a very high-risk population. The Elderly Nutrition Program is funded by the US Department of Health and Human Services to support older individuals’ tenure in the home through meal provision to homebound elders; these meals sustain adequate dietary patterns and improve nutritional intake.Citation26 The home meal program serves the fastest growing older adult population in the US, ie, persons aged 85 years and older.Citation27 In a community partnership study to examine mental health need in the home meal program, 12% of clients receiving meals reported clinically significant depression (Patient Health Question-naire-9 score >9), with an additional 15% reporting mild depressive symptoms, and 13% of clients screened endorsed thoughts of death and dying.Citation28 A recent assessment of mental health need using a research diagnostic interview reported that 27% of aging service clients receiving case management met criteria for a current major depressive episode.Citation29

In this paper, we describe the levels of depression and suicidal ideation among older persons participating in the home meal program and an intervention to improve engagement in mental health treatment delivered in aging services. We hypothesized that diagnostic interviews would yield significant rates of major depression among clients participating in the home meal program who endorse symptoms when screened for depression as part of routine home meal service assessments. We targeted this group of older adults because home meal program recipients require meal service to maintain their independence and untreated depression can increase their potential disability and decline. Regular assessments for home meal program eligibility provide an opportunity to integrate routine depression screening followed by an intervention to link depressed older adults to mental health treatment.

Materials and methods

Target population

The US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Community Living (Administration on Aging) authorizes provision of meals to individuals who are homebound, with nearly 149 million home-delivered meals provided to more than 880,000 homebound individuals across the US in 2009.Citation30 Compared with the overall older adult US population (age ≥60 years), these home meal recipients are more likely to be older, poor, black, and living alone, to be in poor health, have greater difficulty performing everyday tasks, and to be at high nutritional risk.Citation31 To be eligible for a home-delivered meals program, an older adult must be “confined” due to a condition, illness, or injury that restricts the ability of the individual to leave the home except with some type of assistance.

Sample and recruitment

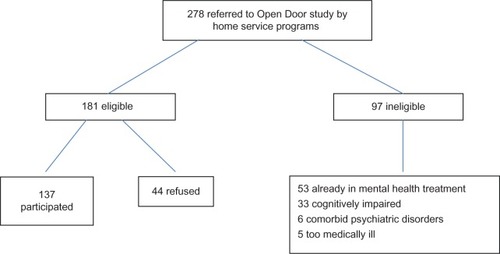

The sample is part of a larger study (National Institute of Mental Health R01 MH079265) to test the effectiveness of the Open Door intervention. Participants are adults aged 60 years or older who are eligible for home meal service in Westchester County and Bronx, NY, USA, and who endorse symptoms when screened for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 or Patient Health Questionnaire-9Citation32 as part of routine home assessment (see ). Once an eligible subject is identified through routine depression screening, verbal consent is obtained for research staff to contact the older adult and describe the study. If the subject chooses to participate, a counselor makes an in-home visit to obtain informed consent and conduct a baseline assessment. Exclusion criteria, evaluated by research staff, include the presence of significant substance abuse or psychotic disorder, active suicidal ideation requiring immediate attention, significant cognitive impairment, aphasia interfering with communication, inability to speak English, or already participating in mental health treatment (either antidepressant medication or psychotherapy). The study was approved by the Weill Cornell institutional review board (Protocol 0707009247).

During baseline assessment, the level of mental health need (depression diagnosis, depression severity, and presence of suicidal ideation), functioning, and attitudes towards depression and its treatment are evaluated. The Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) Axis I disordersCitation33 is used to determine the current diagnosis, and severity ratings are conducted using the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS).Citation34 The inter-rater consistency is 94% for the MADRS between all study raters conducting baseline and follow-up assessments.

Individuals who endorse active or passive suicidal ideation are evaluated using the Suicide Risk AssessmentCitation35 to determine the suicide risk level and an appropriate course of action. The Suicide Risk Assessment questions elicit information about suicidal thoughts, presence of a plan, wish to die, and reasons for living. Mild risk is defined as thoughts about suicide, a strong wish to die, or a past history of attempted suicide. For mild risk, the recommendation is that suicidal thoughts be discussed as part of the mental health treatment being recommended. If the individual has attempted suicide in the past month, has had a previous attempt requiring medical attention, endorses a strong wish to die, has considered a method in the past month, or has thoughts of committing suicide but has not considered a method, then the client is considered intermediate risk. Clients with intermediate risk are reviewed with a supervisor and a contract is created, and with the client’s permission, the client’s primary care clinician or a family member is notified. If there is suicidal intent with nothing preventing the individual from attempting suicide or there is questionable impulse control, then the client is considered high-risk. These clients require immediate intervention (eg, crisis team, police, or hospitalization). These risk assessment and suicide risk review procedures have been used in multiple protocols for community-based research.Citation35,Citation36

Ability to complete instrumental activities of daily living and the number of medical conditions are assessed using the Multi-level Assessment Inventory.Citation37 Cognitive functioning is evaluated using the Mini-Mental Status Examination,Citation38 with individuals who score less than 24 excluded from participation. The level of nutritional risk is evaluated using a standard questionnaire administered by all home meal programs in New York State.Citation39 This questionnaire yields a score from 0 to 21, and an individual score of 6 or greater is considered at high nutritional risk. Chronic pain is assessed using self-report questions to evaluate the presence of painful sensations during the preceding 6 months.Citation40 Participants are also asked if they have fallen during the previous 6 months, and if so, whether they sustained any injuries from a fall and if they saw a physician for these injuries. Prior use of mental health treatment is documented using the Cornell Services Index.Citation41

Engagement intervention

The Open Door intervention is a brief, individualized intervention to identify and address barriers to engagement in mental health treatment among older persons whose depression is detected in aging service settings. The premise of the intervention is that by collaboratively engaging the older adult in the process of seeking mental health treatment, the intervention both creates an engagement plan that is personalized and models the collaborative process of quality mental health treatment.Citation42 A referral is the first step to engagement, but often referrals are not accepted. The Open Door intervention is conducted during three face-to-face, 30-minute intervention meetings in the client’s home with one telephone follow-up. The Open Door intervention was taught during a two-day training provided by the principal study investigator (JAS) with weekly supervision provided for the first 6 months followed by monthly supervision thereafter.

There are five steps to the Open Door intervention: recommend referral, conduct a barriers assessment, define a personal goal that could be achieved with care, provide education about depression treatment options, and finally, address the barriers to accessing care. The Open Door counselor serves a similar function as the patient navigator whose role in a hospital setting is to improve access to cancer screening and treatment.Citation43,Citation44 The Open Door intervention is different from other engagement interventions in two ways. First, the barriers assessed as part of the intervention are empirically defined from research identifying health beliefs and attitudes that predict poor treatment participation outcomes, such as not initiating care,Citation45 dropping out,Citation46 or not following a medication regimen.Citation47 Second, the individualized assessment of barriers goes beyond rational decision-making to elicit the beliefs and concerns, including irrational ideas, that may be underlying the reluctance to seek mental health treatment. In some instances, the intervention allows the client to articulate the fears that s/he may be self-conscious about admitting, but have become the basis for not seeking mental health treatment.

During the Open Door intervention meetings, the counselor uses techniques drawn from motivational interviewing to help mobilize an individual’s intrinsic motivation to seek help.Citation48 The client and counselor use problem-solving techniques to brainstorm about solutions to barriers, weigh the options, and create a specific plan to seek mental health treatment. Sample intervention strategies are shown in . The client’s treatment modality and setting preferences are assessed using a scripted presentation of the available treatment options (eg, primary care physician, mental health provider, research protocol). By participating in this process, the Open Door intervention addresses not only the referral, but also the first steps of the treatment process.

Table 1 Examples of Open Door intervention

Prior to the current study, a small feasibility pilot was conducted with the Department of Senior Programs and Services, which had documented a 22% (18/117) acceptance rate of referrals to a mental health resource using their usual referral procedures. In this feasibility pilot, home meal program participants who screened positive for depression on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 were referred to a mental health resource using the Open Door intervention. Of the 29 participants referred, 20 (62%) accepted a referral to mental health treatment and scheduled a first appointment to be seen by a clinician. This feasibility study supported the delivery of the intervention and the potential to improve mental health referral rates.

Data analysis

This study analyzed data collected during baseline assessment of the Open Door study. All study data were entered in an Access database and converted to files for analyses using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 19.0 software.Citation49 Descriptive analyses were conducted to characterize the sample. Chi-square and t-test analyses were conducted to compare older adults with major depressive disorder and minor or no depression regarding their rates of suicidal ideation, medical conditions, rate of pain, and functioning in instrumental activities of daily living.

Results

Elderly Nutrition Program staff referred 278 individuals who endorsed symptoms when screened for depression as part of routine home meal service assessments to the Open Door program. All clients who screened positive were referred to determine the level of depression and need for mental health treatment. Of those referred, 97 were ineligible (53 were in mental health treatment, 33 had cognitive impairment, six had other psychiatric disorders, and five were too medically compromised to participate). Of 181 eligible individuals, 24% (44/181) refused to participate (see ). The sample consisted of 137 home meal program participants. The demographic characteristics of the sample are described in . In addition to the home meal program, many participants reported using medical support services in the 3 months prior to their enrollment in the home meal program. One third (33%, 45/137) of the sample had the help of a home health aide and most clients (85%, 116/137) had been to at least one medical visit. Almost one in five clients (19%, 26/137) had been hospitalized and 16% (22/137) had made a visit to an emergency room in the previous 3 months.

Table 2 Sample characteristics (n = 137)

Within this sample of home meal recipients who screened positive for depression, half of participants assessed (51%, 70/137) met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder and 13% (18/137) met criteria for minor depression. Older adults who met criteria for major depressive disorder had more medical conditions than those older adults with either minor depression or no depression (t = −2.78, df = 134, P < 0.01). There were no differences between those with major depressive disorder and those with minor depression or no depression in the number of impairments in instrumental activities of daily living (t = −0.81, df = 135, P = 0.42) or those reporting experience of pain during the previous 6 months (χ2 = 1.74, df = 1, P = 0.19). Those with major depressive disorder were also more likely to be at nutritional risk.Citation50

Almost one third (29%, 40/137) of participants endorsed suicidal ideation and received the suicide risk assessment. Within the group of participants whose suicide risk was assessed, 23% (9/40) of clients who screened positive for suicide had intermediate or high risk. Among older adults with major depressive disorder, 47% (33/70) endorsed suicidal ideation and had a risk assessment; with one quarter (24%, 8/33) of clients with major depressive disorder found to be at intermediate risk and requiring a contract or plan. Suicide risk was higher among participants with major depression than those with minor depression or no depression (χ2 = 23.95, df = 2, P < 0.001). Of the older adults without a diagnosis of either minor or major depression, 6% (3/49) endorsed suicidal ideation. Suicide risk was not associated with race, age, gender, or education.

Discussion

This study reinforces the unique opportunity of the aging service network to improve detection of depression and facilitate engagement in mental health treatment to help individuals with significant mental health needs. In this sample of older adults who endorsed symptoms when screened for depression as part of routine home meal service assessments, 51% met research diagnostic criteria for major depression and an additional 13% met criteria for minor depression. This group of older adults reported high rates of suicidal ideation, indicating significant potential risk. This is also a group with mental health need that occurs in the context of significant disability, comorbid medical conditions, and social isolation, with the greatest medical burden, pain, and suicidal ideation among older adults with major depression.

The findings of this study echo the emerging research data documenting mental health need among older adults receiving aging services,Citation5,Citation51 and the sample is consistent with the characteristics reported nationally for home meal program participants.Citation52 While the sampling strategies may vary between studies, the high rate of depression among aging service recipients is consistent with depressive rates reported by other research in this population.Citation5,Citation51 However, this study documents high rates of suicidal ideation in this population (29%), with the highest rate of suicidal ideation reported by adults who met criteria for major depression, where more than half (51%) of home meal program clients with major depression endorsed suicidal ideation. This finding would suggest that aging service staff should have protocols to address suicide ideation and potential risk as they implement depressive screening and referral programs. Building partnerships between mental health providers and aging services may serve as a bridge for older adults who need mental health treatment.Citation53

Home meal program clients also have high levels of disability, medical burden, and vulnerability to falls. Despite limitations in mobility, many home meal program recipients do leave their homes for medical visits, suggesting that there is potential to travel for mental health treatment. The Open Door intervention may offer a strategy to improve engagement in mental health treatment by addressing the need and real barriers to care in this population. The Open Door intervention may improve the perception of acceptability, availability, and accessibility of mental health care by reducing psychologic barriers, providing education about care, and managing the resignation associated with symptoms of depression among community-dwelling depressed elders. Future work should evaluate the acceptability and impact of the Open Door intervention on engagement and attitudes towards mental health treatment, especially stigma.

The limitations of this study include its small sample size and potential bias in recruitment and participation. While the refusal rate was low (24%) for a community-based study, those individuals who refused may have included older adults most reluctant to seek mental health care, and older adults with the greatest barriers. An additional limitation is the study location. The intervention was delivered in urban and suburban areas where mental health resources may be more available than in other areas. Finally, the Open Door intervention focuses on barriers to care at the individual level but does not mitigate provider or system level barriers that may be insurmountable. However, we believe that addressing psychologic obstacles will improve access and help older adults to anticipate and navigate the often intractable provider and system barriers, such as limited providers.Citation2

Despite these limitations, our study findings indicate real and substantial mental health treatment needs among older adults with depressive symptoms identified in the home meal program. The Open Door intervention may offer a useful strategy to work to overcome barriers to treatment and improve engagement that may fit within the roles and responsibilities of aging service staff who recommend and link clients to multiple services. Collaboration with community providers on the design and implementation of intervention increases the likelihood that the intervention will be sustained ultimately by the community.Citation54

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH079265).

Disclosure

The authors have no financial conflicts to disclose in this work.

References

- ByersALYaffeKCovinskyKEFriedmanMBBruceMLHigh occurrence of mood and anxiety disorders among older adults: The National Comorbidity Survey ReplicationArch Gen Psychiatry201067548949620439830

- Institute of Medicine of the National AcademiesThe mental health and substance use workforce for older adults: in whose hands?Washington, DCNational Academies Press2012 Available from: http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13400Accessed July 25, 2013

- RauePJSireyJADesigning personalized treatment engagement interventions for depressed older adultsPsychiatr Clin North Am201134248950021536170

- GlanzKLewisFMRimerBKHealth Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and PracticeSan Francisco, CAJossey Bass2002

- GumAMIserLPetkusABehavioral health service utilization and preferences of older adults receiving home-based aging servicesAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201018649150121217560

- CharneyDSReynoldsCF3rdLewisLDepression and Bipolar Support Alliance. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance consensus statement on the unmet needs in diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders in late lifeArch Gen Psychiatry200360766467212860770

- BruceMLSeemanTEMerrillSSBlazerDGThe impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur Studies of Successful AgingAm J Public Health19948411179617997977920

- BarryLCMurphyTEGillTMDepressive symptoms and functional transitions over time in older personsAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201119978379121873834

- EggermontLHPenninxBWJonesRNLeveilleSGDepressive symptoms, chronic pain, and falls in older community-dwelling adults: the MOBILIZE Boston StudyJ Am Geriatr Soc201260223023722283141

- United States Department of Health and Human ServicesMental Health: A Report of the Surgeon GeneralRockville, MDUnited States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health1999 Available from: http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/access/NNBBHS.pdfAccessed July 25, 2013

- AbramsRCLachsMMcAvayGKeohaneDJBruceMLPredictors of self-neglect in community-dwelling eldersAm J Psychiatry20021591724173012359679

- ShelineYIHigh prevalence of physical illness in a geriatric psychiatric inpatient populationGen Hosp Psychiatry19901263964002245925

- UnützerJPatrickDLSimonGDepressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older. A 4-year prospective studyJAMA199727720161816239168292

- DrussBGRohrbaughRMRosenheckRADepressive symptoms and health costs in older medical patientsAm J Psychiatry1999156347747910080569

- LuberMPMeyersBSWilliams-RussoPGDepression and service utilization in elderly primary care patientsAm J Geriatr Psychiatry20019216917611316621

- SheeranTBrownELNassisiPBruceMLDoes depression predict falls among home health patients? Using a clinical-research partnership to improve the quality of geriatric careHome Healthc Nurse200422638438915184780

- BlazerDGDepression in late life: review and commentaryJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci20035824926512634292

- UnützerJSimonGBelinTRDattMKatonWPatrickDCare for depression in HMO patients aged 65 and olderJ Am Geriatr Soc200048887187810968289

- BruceMLLeafPJPsychiatric disorders and 15-month mortality in a community sample of older adultsAm J Public Health19897967277302786347

- GalloJJBognerHRMoralesKHPostEPTen HaveTBruceMLDepression, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and two-year mortality among older, primary-care patientsAm J Geriatr Psychiatry200513974875516166403

- BruceMLLeafPJRozalGPFlorioLHoffRAPsychiatric status and 9-year mortality data in the New Haven Epidemiologic Catchment Area StudyAm J Psychiatry199415157167218166313

- MurrayCJVosTLozanoRDisability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010Lancet201238098592197222323245608

- MarinoPSireyJEpidemiology of late life mood disorders: rates, measures and populationsLate Life Mood DisordersOxford, UKOxford University Press2012

- ByersALAreanPAYaffeKLow use of mental health services among older Americans with mood and anxiety disordersPsychiatr Serv2012631667222227762

- BarryLCAbouJJSimenAAGillTMUnder-treatment of depression in older personsJ Affect Disord2012136378979622030136

- FrongilloEAWolfeWSImpact of participation in home-delivered meals on nutrient intake, dietary patterns, and food insecurity of older persons in New York stateJ Nutr Elder201029329331020711924

- Administration on AgingPercentage Increase of the 60+ US. Population from the 2000 Census to the 2010 Census Available from: http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/Aging_Statistics/Census_Population/census2010/Index.aspxAccessed April 25, 2012

- SireyJABruceMLCarpenterMDepressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among older adults receiving home delivered mealsInt J Geriatr Psychiatry200823121306131118615448

- RichardsonTMFriedmanBPodgorskiCDepression and its correlates among older adults accessing aging servicesJ Nurs Care Qual2011204346354

- GreenleeKTestimony on Senior Hunger and the Older Americans Act2011 Available from: http://www.help.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Greenlee.pdfAccessed August 16, 2013

- Administration on AgingNutrition Program EvaluationDepartment of Health and Human ServicesServing Elders At Risk; The Older Americans Act Nutrition Programs – National Evaluation of the Elderly Nutrition Program, 1993–1995 Available from: http://www.aoa.gov/aoaroot/program_results/Nutrition_Report/eval_report.aspxAccessed July 25, 2013

- LöweBKroenkeKGräfeKDetecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2)J Psychosom Res200558216317115820844

- SpitzerRGibbonMWilliamsJBStructured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders (SCID)Washington, DCAmerican Psychiatric Association Press Inc1995

- MontgomerySAAsbergMA new depression scale designed to be sensitive to changeBr J Psychiatry1979134382389444788

- RauePJBrownELMeyersBSSchulbergHCBruceMLDoes every allusion to possible suicide require the same response? A structured method for assessing and managing riskJ Fam Pract200655760561216822448

- BruceMLBrownELRauePJA randomized trial of depression assessment intervention in home healthcareJ Am Geriatr Soc200755111793180017916119

- LawtonMPBrodyEMAssessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living measureGerontologist1969931791865349366

- FolsteinMFFolsteinSEMcHughPR“Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinicianJ Psychiatr Res19751231891981202204

- GuigozYVellasBGarryPJAssessing the nutritional status of the elderly: The Mini Nutritional Assessment as part of the geriatric evaluationNutr Rev1996541 Pt 2S59S658919685

- ElliottAMSmithBHPennyKISmithWCChambersWAThe epidemiology of chronic pain in the communityLancet199935491861248125210520633

- SireyJAMeyersBSTeresiJAThe Cornell Service Index as a measure of health service usePsychiatr Serv200556121564156916339619

- SireyJAEngaging to improve engagementPsychiatr Serv201364320523450380

- FreemanHPPatient navigation: a community based strategy to reduce cancer disparitiesJ Urban Health200683213914116736361

- JandorfLGutierrezYLopezJChristieJItzkowitzSHUse of a patient navigator to increase colorectal cancer screening in an urban neighborhood health clinicJ Urban Health200582221622415888638

- LeafPJBruceMLTischlerGLThe differential effect of attitudes on the use of mental health servicesSoc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol1986214187192

- SireyJABruceMLAlexopoulosGSPerceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depressionAm J Psychiatry2001158347948111229992

- SireyJABruceMLAlexopoulosGSPerlickDAFriedmanSJMeyersBSStigma as a barrier to recovery: perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherencePsychiatr Serv200152121615162011726752

- MillerWRRollnickSMeeting in the middle: motivational interviewing and self-determination theoryInt J Behav Nutr Phys Act201292522385872

- IBMCorpReleased 2010. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0Armonk, NYIBM Corp

- KniesKSMarinoPThe relation of depression and nutritional risk among vulnerable older adultsPresented at the 2012 Aging in America conferenceWashington, DCMarch 28 to April 1, 2012

- RichardsonTMFriedmanBPodgorskiCDepression and its correlates among older adults accessing aging servicesAm J Geriatr Psychiatry201220434635422434017

- ColelloKJOlder Americans Act: Title III Nutrition Services ProgramWashington, DCCongressional Research Service2011 Available from: https://www.google.co.nz/search?q=Colello+KJ.+Older+Americans+Act%3A+Title+III+Nutrition+Services+Program.+Congressional+Research+Service%3B+2011.&oq=Colello+KJ.+Older+Americans+Act%3A+Title+III+Nutrition+Services+Program.+Congressional+Research+Service%3B+2011&aqs=chrome.0.69i57.1871j0&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8Accessed July 25, 2013

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and Administration on AgingIssue Brief 1: Aging and Behavioral Health Partnerships in the Changing Health Care Environment Available from: http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/AoA_Programs/HPW/Behavioral/docs2/Issue%20Brief%201%20Partnerships.pdfAccessed July 25, 2013

- WellsKMirandaJBruceMLAlegriaMWallersteinNBridging community intervention and mental health services researchAm J Psychiatry2004161695596315169681