Abstract

Constipation is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder, with prevalence in the general population of approximately 20%. In the elderly population the incidence of constipation is higher compared to the younger population, with elderly females suffering more often from severe constipation. Treatment options for chronic constipation (CC) include stool softeners, fiber supplements, osmotic and stimulant laxatives, and the secretagogues lubiprostone and linaclotide. Understanding the underlying etiology of CC is necessary to determine the most appropriate therapeutic option. Therefore, it is important to distinguish from pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD), slow and normal transit constipation. Evaluation of a patient with CC includes basic blood work, rectal examination, and appropriate testing to evaluate for PFD and slow transit constipation when indicated. Pelvic floor rehabilitation or biofeedback is the treatment of choice for PFD, and its efficacy has been proven in clinical trials. Surgery is rarely indicated in CC and can only be considered in cases of slow transit constipation when PFD has been properly excluded. Other treatment options such as sacral nerve stimulation seem to be helpful in patients with urinary dysfunction. Botulinum toxin injection for PFD cannot be recommended at this time with the available evidence. CC in the elderly is common, and it has a significant impact on quality of life and the use of health care resources. In the elderly, it is imperative to identify the etiology of CC, and treatment should be based on the patient’s overall clinical status and capabilities.

Introduction

Constipation is a common functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder. The prevalence of constipation in the general population is approximately 20% although it can range anywhere from 2% to 27%, depending on the definition used and population studied.Citation1,Citation2 A population-based study reported that the cumulative incidence of chronic constipation (CC) is higher in the elderly (~20%) compared to a younger population.Citation3 Severe constipation is more common in elderly women, with rates of constipation two to three times higher than that of their male counterparts.Citation3–Citation5 The Rome III criteria use a combination of objective (stool frequency, manual maneuvers needed for defecation) and subjective (straining, lumpy or hard stools, incomplete evacuation, sensation of anorectal obstruction) symptoms to define constipation.Citation6

Treatments for CC have varying degrees of efficacy. Available therapeutic options include stool softeners, fiber supplements, osmotic and stimulant laxatives, and the secretagogues lubiprostone and linaclotide. Epidemiologic studies demonstrate a higher prevalence laxative use in the elderly,Citation3,Citation7–Citation10 and elderly patients residing in nursing homes have a greater prevalence of constipation (up to 50%), with up to 74% of them using daily laxatives.Citation4,Citation10,Citation11

The economic impact of CC in the US is significant, with an estimated 2.5 million physician visits and 100,000 hospitalizations annually.Citation12 Chronic constipation also negatively impacts health related quality of life, with psychological and social consequences.Citation13,Citation14 Therefore, it is important to understand the etiology and management of constipation in this population. This review will also discuss pelvic floor disorders, slow transit constipation, their clinical presentations, and treatment options.

Pelvic floor function

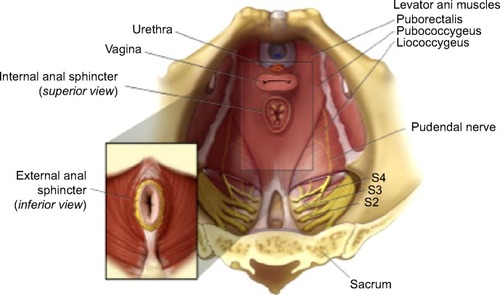

Disorders of the pelvic floor manifesting with both constipation and disorders of incontinence are prevalent in the elderly population. The pelvic floor comprises a group of muscles that have a crucial role in the process of defecation. Understanding the anatomy of the pelvic floor is essential to recognize its role in constipation. The functional anatomy of the pelvic floor consists of the pelvic diaphragm (levator ani and coccygeus muscles) and anal sphincters (external and internal), innervated by the sacral nerve roots (S2–4) and the pudendal nerve (). Normal functioning of this neuromuscular unit allows for efficient and complete elimination of stool from the rectum.

Figure 1 Anatomy of pelvic floor.

Although studies of constipation in tertiary care centers have described a prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) of 50% or more,Citation15,Citation16 the prevalence of PFD in constipation in the elderly is not well known. PFD is frequently seen in elderly women, particularly those with history of anorectal or pelvic surgery and other pelvic floor trauma such as childbirth.Citation17–Citation20 PFD is not limited to defecation disorders but also can present with urinary tract disorders and sexual dysfunction. As it relates to constipation, PFD may be more appropriately termed a functional defecation disorder, which can be characterized by 1) paradoxical contractions or inadequate relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles, or 2) inadequate propulsive forces during attempted defecation.Citation20 shows the anatomy of the pelvic floor (courtesy of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA; permission requested).

Pathophysiology

The two major etiologies of constipation are PFD and slow colonic transit. Patients in whom no cause is identified can be defined as having normal transit constipation. Psychosocial and behavioral issues are also important in the development of constipation. These issues need to be taken into consideration in the elderly, as some may have additional mechanisms that will impact bowel function.

Aging process and the enteric nervous system

The elderly population is impacted by age-related cellular dysfunction that affects plasticity, compliance, altered macroscopic structural changes (ie, diverticulosis), and altered control of the pelvic floor. These molecular and physiologic changes are thought to be involved in the constipation disorders seen in the elderly, and some have been described.Citation18

Studies have demonstrated altered colonic motility mediated by age-related neuronal loss and increased number of altered and dysfunctional myenteric ganglia.Citation20,Citation21 In addition, studies using surgical samples from the descending colon have shown an age-related decrease in inhibitory junction potentials, suggesting a decrease in inhibitory nerves in the smooth muscle membrane.Citation22 A study by Bernard et al demonstrated the selective age-related loss of neurons that express choline acetyltransferase that was accompanied by sparing of nitric oxide-expressing neurons in the human colon.Citation23 Furthermore, a study has reported higher sensory thresholds to rectal distention suggesting altered rectal sensitivity in the elderly.Citation24 The factors that contribute to alteration in motility during aging are complex, with different effects in different regions of the gut.Citation25 Additional proposed physiologic changes in bowel function in the elderly are summarized in .

Table 1 Proposed physiologic colonic changes in the elderly

Pelvic floor dysfunction

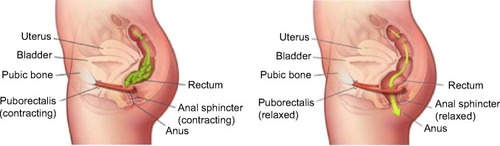

Defecation occurs through a neurologically mediated series of coordinated muscle movements of the pelvic floor and anal sphincters (). This process is complex, and dysfunction can lead to abnormal stool expulsion or obstructive defecation.Citation30,Citation31 Abnormalities in this process include failed relaxation of the pelvic floor, paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor muscles, or the inability to produce the necessary propulsive forces needed in the rectum to expel the stool completely. Earlier studies of the pelvic floor in the elderly using anorectal manometry (ARM) did not show differences in anorectal function between the elderly and younger counterparts.Citation32,Citation33 However, other physiologic studies show various abnormalities with aging, such as decreased rectal compliance, increased urge thresholds for defecation, and decreased rest and squeeze pressures in the anal canal.Citation17–Citation19,Citation34,Citation35

Figure 2 Dynamics of defecation.

In addition, specific anatomic abnormalities such as rectoceles, sigmoidoceles, and rectoanal intussusception, among others commonly seen in elderly women, also impact the defecation process. Understanding the role and function of the pelvic floor in the development of constipation and its impact in the elderly population is essential for the care of the geriatric population.

illustrates the dynamics of defecation. At rest (left panel), the puborectalis sling holds the rectum at an angle and the anal sphincters are closed. On normal defecation (right panel), 1) the puborectalis relaxes, 2) the anorectal angle straightens, 3) the pelvic floor descends, and 4) the anal sphincter relaxes, allowing stool expulsion when accompanied by adequate propulsive force (courtesy of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA; permission requested).

Colonic transit

Delayed colonic transit has been described as a cause of constipation in the elderly. There has been some controversy on the effect of aging on colonic transit. Research studies have described delayed colonic transit in the elderly,Citation36–Citation38 whereas others have described no significant difference in colonic transit between the elderly and younger patients.Citation39,Citation40 However, although decreased propulsive forces of the colon have been described in the elderly,Citation41 there are numerous secondary causes of delayed colonic transit that are commonly seen in the elderly (). Delayed colonic transit is more often secondary to modifiable causes such as medication side effects (ie, narcotic and/or anticholinergics) and PFD that results in secondary delay of colonic transit by inhibitory reflexes.Citation42,Citation43

Table 2 Common associations with constipation in the elderly

Psychosocial and behavioral factors

Constipation is associated with significant psychological impairment.Citation44–Citation46 The elderly population is at risk of significant psychological and social distress since they suffer from greater decreased mobility, altered dietary intake, dependency on others, and issues that may develop from social isolation. Defecation disorders interfere with quality of life and may alter interpersonal, intimate, and interfamily relationships.Citation47–Citation49

Furthermore, the elderly may have decreased awareness to the desire to defecate that can lead to CC with fecal retention. Subsequently, only large stool volumes may be perceived and lead to difficulty with rectal evacuation.Citation50 Awareness of these psychological and behavioral factors are important, and early identification and intervention are helpful in this vulnerable population.

Clinical presentation

The clinical presentation of a patient suffering from constipation is heterogenous. Patients may not always present with the expected decreased bowel frequency and altered consistency but can also present with almost daily bowel movements that require excessive straining, rectal or vaginal digitation to facilitate stool expulsion accompanied with the sensation of incomplete evacuation. The latter are features suggestive of PFD that can also have associated urinary symptoms, such as urine retention and sexual dysfunction, such as dyspareunia.Citation49,Citation51

The clinical presentation of constipation in the elderly appears to be different from other populations. The elderly report more frequent straining, rectal or vaginal digitation, and the sensation of rectal blockage.Citation4,Citation52,Citation53 In addition, many constipated elderly patients experience fecal seepage and are frequently misdiagnosed with fecal incontinence.Citation54 In this setting, patients often have a history of constipation with the sensation of incomplete rectal evacuation, with frequent and incomplete bowel movements and excessive wiping. Often, these patients are prescribed antidiarrheals for presumed incontinence, which worsen the situation with fecal impaction and overflow incontinence secondary to obstruction to defecation. In addition, fecal impaction can cause stercoral ulcers and rectal bleeding. A thorough history and examination, which needs to include a complete rectal examination, are essential.

Severe constipation can lead to secondary alterations in GI motility, resulting in upper GI symptoms. Patients with CC have been shown to have delayed gastric emptying, right colon transit, and prolonged mouth-to-cecum transit time.Citation2 Patients with CC often present with concomitant dyspepsia, abdominal cramping, bloating, flatulence, heartburn, nausea, and vomiting.Citation5,Citation46,Citation55–Citation57

Details of the medical history should include the use of constipating medications, physical or mental health decline, coexisting medical conditions, dietary habits, and general psychosocial situation. Use of chronic narcotics should also be addressed, especially in patients with chronic pain. A personal or family history of colon cancer should be ascertained as well as a prior colonoscopy.

Diagnostic approach

Patients typically present to their primary care physician for the initial evaluation and management of constipation. Initially, it is important to determine the patient’s understanding of constipation. Standard diagnostic studies typically include baseline blood work to exclude any significant metabolic and structural tests to evaluate for anatomic abnormalities. Patients with persistent constipation, normal investigations, and a failed response to initial empiric therapies are the ones typically referred to the gastroenterologist. Pursuing relevant studies that help categorize patients as to the cause of their constipation facilitates selection of the appropriate therapy for each specific physiologic subgroup.Citation2,Citation51

History and physical examination

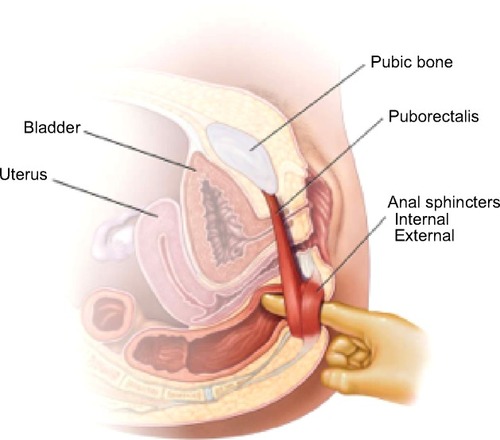

A comprehensive history focusing on relevant clinical features, including a thorough medication review is needed. The physical examination is not complete without a thorough perianal and digital rectal examination. This portion of the exam not only assess for mass lesions, anal strictures, fissures, or stool impaction but on the mechanics of defecation.Citation58,Citation59

depicts the anorectal examination (courtesy of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA; permission requested). With the patient in the left lateral position, the examiner should assess 1) resting sphincter tone and presence of spasm, 2) sensation, including the presence of pain, 3) the ability to squeeze, and 4) coordination of the pelvic floor and rectal muscles and extent of perineal descent during simulated defecatory straining (expelling the examiner’s finger).

Figure 3 Anorectal examination.

Metabolic and structural evaluation

Although important, particularly for individuals on multiple medications with various comorbid conditions, routine lab tests such as a complete blood count, electrolytes, calcium levels, and thyroid function studies rarely identify the cause of CC. Further, the yield of colonoscopy and barium enema in patients with constipation is the same as the general population.Citation60,Citation61 These diagnostic studies are indicated in patients with alarm symptoms such as hematochezia or weight loss and for the acute onset of constipation in the elderly. Routine colon cancer screening is recommended for all patients 50 years or older. Plain abdominal radiographs are helpful to assess fecal load, impaction, or obstruction.

Pelvic floor evaluation

Assessment of the pelvic floor function is essential to determine if PFD is the underlying cause of constipation. Patients who have failed initial laxative therapy or who have symptoms suggestive of PFD should undergo formal testing. However, the reliability and comparability of many tests are unknown. Current available tests include ARM, standard defecography, and dynamic magnetic resonance imaging defecography. ARM has the ability to assess tone, strength, sensation, control, and coordination with defecatory straining. ARM with balloon expulsion testing provides measurements that relay key information about the motor and sensory control of the anorectum and pelvic floor.Citation62–Citation64 Failed balloon expulsion, abnormal sensory thresholds, hypertensive sphincters, and dyssynergic pattern during attempted defecation are all findings seen in ARM testing that support the diagnosis of PFD. Defecography can identify the presence of anatomic abnormalities that will impact rectal evacuation.Citation65 Significant anatomical abnormalities of the pelvic floor (ie, pelvic organ prolapse, rectocele, among others) and inability to evacuate the rectal gel are some features seen in defecography that are suggestive of PFD. There is no single gold standard test to confidently diagnose PFD, and more than one test is required for the proper diagnosis. In certain cases, assessment by a trained physical therapist in pelvic floor retraining is necessary to confirm the diagnosis of PFD. summarizes clinical presentation and common diagnostic findings in patients with PFD.

Table 3 Diagnostic findings in patients with defecatory disorders

Colonic transit

Colon transit studies objectively determine the rate of stool movement through the colon, although clinically it is rarely indicated. Currently available colon transit studies include the radiopaque markers (ROM), colonic scintigraphy, and the wireless motility capsule (WMC). ROM studies are inexpensive and are a widely available way to assess colon transit.Citation66,Citation67 In addition to total marker counts, marker distribution may also be helpful, as proximal retention suggests colonic dysfunction, whereas the retention of markers exclusively in the lower left colon is more suggestive of PFD. Scintigraphic techniques allow for shorter studies (24–48 hours) and decreased radiation exposure.Citation68,Citation69 The WMC or SmartPill® has sensors that measures pH, pressure, and temperature, which collectively determine regional and whole gut transit times of the GI tract.Citation70 A recent study compared the WMC with ROM in 39 constipated and eleven healthy older subjects (≥65 years). The device agreement for slow colonic transit was 88%, with good correlation between WMC and ROM in elderly patients, suggesting that the WMC was a useful diagnostic device of delayed colonic transit in elderly constipated patients.Citation71

Factors that will impact GI transit include PFD, medications, diet, and the presence of excessive stool or impaction.

Treatment

Selection of treatment in CC depends on the underlying physiologic cause. In the elderly population it is important to consider other factors that impact constipation such as dehydration, dementia among others prior to initiating a specific therapy ().Citation72 briefly summarizes commonly used agents to treat constipation and their mechanisms of action. Generally, fiber supplementation is a reasonable initial therapeutic approach; however, patients that do not respond to fiber supplementation can be advanced to osmotic laxatives. The latter should be titrated to clinical response. Stimulant laxatives and prokinetic agents should be reserved for patients who are refractory to fiber supplements or osmotic laxatives. Surgery is rarely indicated for constipation, exclusion of PFD is essential, and surgical outcomes in the elderly are uncertain. Fecal impaction should be cleared before instituting maintenance regimens. Treatment for CC also needs to be tailored to the patient’s medical history, medications, overall clinical status, mental and physical abilities, tolerance to various agents, and realistic treatment prospects. Patients that are institutionalized need to be addressed with standardized and supervised bowel programs.

Table 4 Clinical factors that impact bowel function in the elderly

Table 5 Summary of commonly used laxative agents

Bulking agents

Fiber supplementation is a reasonable first step in the management of CC. Soluble, but not insoluble, fiber agents facilitate bowel function by increasing water absorbency capacity of stool resulting in improved stool frequency and consistency.Citation73 Trials looking at bulking agents are of suboptimal design, and most are plagued by small sample sizes and short study duration.Citation74 Common reported side effects include bloating, gas, and distention, but these symptoms often decrease with time. Synthetic supplements are often better tolerated. Patients with slow transit constipation or PFD will likely not benefit from fiber supplementation.

Although increasing water intake alone has not been shown to improve constipation, maintaining adequate fluid intake is important with fiber supplementation to avoid excessive bulk, which may exacerbate CC. Fluid intake needs to be monitored in patients with cardiac or renal disease, and the need to maintain adequate hydration may be a limitation for some.

Laxatives

Available laxatives in the marketplace include osmotic and stimulant laxatives (). Osmotic laxatives are a reasonable choice for patients not responding to fiber supplementation. Laxative selection should be based on relevant medical history such as cardiac or renal status, possible drug interactions, cost, and side effects. There is no clear superior osmotic agent; therefore, the dose should be titrated to the clinical response.

For chronic or more severe constipation, regular dosing is indicated. Per US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved prescribing information, high doses of polyethylene glycol may produce excessive stool frequency, especially in elderly nursing home residents, and nausea, abdominal bloating, cramping, and flatulence may occur.Citation74–Citation76 Stimulant laxatives, which promote intestinal motility through high-amplitude contractions, do not seem to lead to bowel injury contrary to prior belief.Citation77,Citation78 However, these drugs are better reserved for those with a failed response to osmotic agents and may be required in the management of opioid-induced constipation. Effective for many patients, studies with laxatives in the elderly are limited and are of suboptimal design.Citation79 Abdominal discomfort, electrolyte imbalances, allergic reactions, and hepatotoxicity have been reported.Citation80 There needs to be caution with the use of magnesium-based laxatives in patients with renal disease as there are a few case reports of severe hypermagnesemia.Citation80

Stool softeners, suppositories, and enemas

Stool softeners, which enhances softer stool consistency, are overall of limited efficacy.Citation81,Citation82 Suppositories (ie, glycerin and bisacodyl) help initiate or facilitate rectal evacuation. They may be used alone, but preferentially in conjunction with meals to capture the gastrocolic reflex or in conjunction with other agents.Citation83 Suppositories, which usually work within minutes, may be tried as part of a behavioral program for those with obstructed defecation and in institutionalized patients. Enemas may be used judiciously on an as-needed basis, particularly for obstructed defecation and to avoid fecal impaction. Tap water enemas seem safe for more regular use. Electrolyte imbalances such as hyperphosphatemia are more common with phosphate enemas and regular use is discouraged.Citation84 Soapsuds enemas can cause rectal mucosal damage with colitis and are not routinely recommended.Citation85

Prokinetics

Prokinetic agents exert their action through the 5- hydroxytryptamine type 4 receptor of the enteric nervous system, stimulating secretion and motility. Cisapride has been removed from the market due to cardiovascular side effects, with fatal cardiac arrhythmias due to its effect in QT interval prolongation.

Tegaserod was effective for CC in men and women younger than 65 years,Citation86,Citation87 but data in the elderly is lacking. Although the drug seems effective in the management of constipation, use has been markedly restricted secondary to the risk of cardiac events with ischemia. Prucalopride, a 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 4 agent similar to tegaserod, accelerates colonic transit in patients with constipation, and therapeutic trials have demonstrated efficacy for severe constipation.Citation88,Citation89 Prucalopride for 4 weeks in elderly nursing home residents was safe and well tolerated, with no adverse cardiac side effects and QT interval prolongation.Citation90 Prucalopride is currently not approved for use in the US by the FDA.

Secretagogues

Lubiprostone is a bicyclic fatty acid that activates type 2 chloride channels on the apical membrane of the enterocytes, which results in the chloride secretion with water and sodium diffusion. Its efficacy has been proved in various clinical trials.Citation91–Citation93 However, its effectiveness is limited by the side effect of nausea in approximately 25%–30% of patients with CC, but nausea may improve if taken with food.Citation93 The indication for lubiprostone in patients with a primary problem of PFD is not established.

Linaclotide, a guanylin and uroguanylin analog, increases intestinal secretion by activation of the guanylate cyclase receptor.Citation94 Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of linaclotide in CC in improving stool consistency, straining, abdominal discomfort, bloating, global assessments, and quality of life.Citation95 The most common reported side effect is diarrhea. Caution should be used with these medications in light of their side-effect profile, cost, and efficacy compared to simple, less expensive alternatives.

Pelvic floor rehabilitation (biofeedback)

Pelvic floor rehabilitation or biofeedback is the treatment of choice for PFD. The goals of therapy include educating patients about PFD, coordinating increased intra-abdominal pressure with pelvic floor muscles relaxation during evacuation, and practicing simulated defecation with a balloon.Citation96 In some specialized centers, sensory retraining of the rectum can be done to restore rectal sensation, especially in the cases of rectal hyposensitivity. There are no obvious adverse effects of treatment. Uncontrolled studies suggest that biofeedback is effective in more than 70% of patients, and these findings have been confirmed in several randomized, controlled trials.Citation97–Citation100 Biofeedback has been shown to be superior to laxatives in patients with PFD, and the effect was durable.Citation98 The key is identifying the problem and available therapeutic resources. A randomized trial of biofeedback for PFD in the elderly showed improvement in physiologic measures and in bowel function after eight sessions in 1 month.Citation101 In addition, psychiatric comorbidities need to be addressed early and treated prior or concomitantly with therapy as data suggests that it may play a significant role.Citation48 Concomitant slow colon transit frequently requires simultaneous treatment and can improve once the PFD has been rehabilitated.

Surgery

Rarely indicated, subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis is the treatment of choice for refractory slow transit constipation in cases when PFD is excluded.Citation102,Citation103 Outcomes in the elderly are uncertain. Complications include diarrhea, incontinence, and bowel obstruction.Citation104 Extra caution should be used in patients with abdominal pain, which tend to respond poorly, and this needs to be explained prior to surgery. Results of segmental colonic resections for constipation are disappointing compared to ileorectal anastomosis.Citation105

Surgical indications for PFD are poorly defined, and surgery should be considered only if functional significance can be determined.Citation103,Citation105 The stapled transanal resection was intended to repair rectal intussusception and rectoceles by removing redundant mucosa. However, these anatomical abnormalities have been widely thought to be secondary to PFD since the relationship of these findings and CC symptoms is weak. Moreover, long-term outcomes of patients that seemed to be adequate candidates for the stapled transanal resection procedure have not been promising.Citation2 Division of the puborectalis is not recommended.Citation106 Overall, treatment of the underlying PFD first is a reasonable treatment approach, with surgery reserved for those not responding to more conservative therapy.

Other therapies

Alternative therapies to manage CC included sacral nerve stimulation and botulinum toxin injection therapy for PFD. Sacral nerve stimulation has been shown to be helpful in some small trialsCitation107 and may be useful for patients with combined urinary dysfunction. Botulinum toxin therapy cannot be recommended based on the available data.Citation108,Citation109

Additional comments

Adjunctive therapy may be necessary for psychopathology associated with CC, and maintaining adequate caloric intake is essential. Evidence does not support the popular notion that toxins from constipation harm the body or that irrigation is needed.

There is no obvious significance of an elongated colon (dolichocolon), and surgical shortening does not lead to reliable clinical improvement.Citation78 Likewise, physical activity and water intake are controversial subjects, with unclear associations with colon transit and constipation.Citation78 There is no value in over hydrating a patient; families, long-term care facilities, and physicians should just guard against dehydration. Although mineral oil, colchicine,Citation110 and misoprostolCitation111,Citation112 may improve constipation, these agents have potential side effects and complications that likely outweigh any potential benefits. Their use in the elderly has not been explored and not recommended. Alteration of the bacterial milieu in the colon has been associated with slow transit constipation.Citation113,Citation114

Summary

CC in the elderly is common, and it has a significant impact on quality of life and the use of health care resources. A careful history, medication assessment, and physical examination are helpful in obtaining relevant clues that aid direct management. Physiologic categorization of the cause leading to patient presentation improves management outcomes, and it is important to consider that many causes can be present in one patient, and many factors influence the clinical presentation of an older patient. Fiber supplementation and osmotic laxatives are an effective first line of therapy for many patients. A consistent history or inadequate response to standard initial therapy should prompt an assessment for PFD. If identified, and the patient is a reasonable treatment candidate, pelvic floor rehabilitation (biofeedback) is the treatment of choice. Surgery is rarely indicated in CC. Special effort should be taken to identify features inherent to the elderly, and treatment should be based on the patient’s overall clinical status and capabilities.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- HigginsPDJohansonJFEpidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic reviewAm J Gastroenterol200499475075915089911

- BharuchaAEPembertonJHLockeGRAmerican Gastroenterological Association technical review on constipationGastroenterology2013144121823823261065

- ChoungRSLockeGRSchleckCDZinsmeisterARTalleyNJCumulative incidence of chronic constipation: a population-based study 1988–2003Aliment Pharmacol Ther20072611–121521152817919271

- TalleyNJFlemingKCEvansJMConstipation in an elderly community: a study of prevalence and potential risk factorsAm J Gastroenterol199691119258561137

- WaldAScarpignatoCMueller-LissnerSA multinational survey of prevalence and patterns of laxative use among adults with self-defined constipationAliment Pharmacol Ther200828791793018644012

- LongstrethGFFunctional bowel disorders: functional constipationDrossmanDAThe Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders3rd edLawrence, KSAllen Press2006515523

- WhiteheadWEDrinkwaterDCheskinLJHellerBRSchusterMMConstipation in the elderly living at home. Definition, prevalence, and relationship to lifestyle and health statusJ Am Geriatr Soc19893754234292539405

- DonaldIPSmithRGCruikshankJGEltonRAStoddartMEA study of constipation in the elderly living at homeGerontology19853121121182987086

- HarariDGurwitzJHAvornJBohnRMinakerKLBowel habit in relation to age and gender. Findings from the National Health Interview Survey and clinical implicationsArch Intern Med199615633153208572842

- HarariDGurwitzJHAvornJChoodnovskiyIMinakerKLConstipation: assessment and management in an institutionalized elderly populationJ Am Geriatr Soc19944299479528064102

- PrimroseWRCapewellAESimpsonGKSmithRGPrescribing patterns observed in registered nursing homes and long-stay geriatric wardsAge Ageing198716125283105271

- SonnenbergAKochTRPhysician visits in the United States for constipation: 1958 to 1986Dig Dis Sci19893446066112784759

- BongersMEBenningaMAMaurice-StamHGrootenhuisMAHealth-related quality of life in young adults with symptoms of constipation continuing from childhood into adulthoodHealth Qual Life Outcomes200972019254365

- WangJPDuanLPYeHJWuZGZouBAssessment of psychological status and quality of life in patients with functional constipationZhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi2008476460463 Chinese19040060

- CostillaVCFoxx-OrensteinAEConstipation in adults: diagnosis and managementCurr Treat Options Gastroenterol201412331032125015533

- CostillaVCFoxx-OrensteinAEConstipation: understanding mechanisms and managementClin Geriatr Med201430110711524267606

- BannisterJJAbouzekryLReadNWEffect of aging on anorectal functionGut19872833533573570039

- CamilleriMLeeJSViramontesBBharuchaAETangalosEGInsights into the pathophysiology and mechanisms of constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, and diverticulosis in older peopleJ Am Geriatr Soc20004891142115010983917

- LaurbergSSwashMEffects of aging on the anorectal sphincters and their innervationDis Colon Rectum19893297377422758941

- YuSWRaoSSAnorectal physiology and pathophysiology in the elderlyClin Geriatr Med20143019510624267605

- HananiMFelligYUdassinRFreundHRAge-related changes in the morphology of the myenteric plexus of the human colonAuton Neurosci20041131–2717815296797

- KochTRCarneyJAGoVLSzurszewskiJHInhibitory neuropeptides and intrinsic inhibitory innervation of descending human colonDig Dis Sci19913667127181674467

- BernardCEGibbonsSJGomez-PinillaPJEffect of age on the enteric nervous system of the human colonNeurogastroenterol Motil2009217746e4619220755

- LagierEDelvauxMVellasBInfluence of age on rectal tone and sensitivity to distension in healthy subjectsNeurogastroenterol Motil199911210110710320590

- SaffreyMJAgeing of the enteric nervous systemMech Ageing Dev20041251289990615563936

- Gomez-PinillaPJGibbonsSJSarrMGChanges in interstitial cells of cajal with age in the human stomach and colonNeurogastroenterol Motil2011231364420723073

- SinghJKumarSKrishnaCVRattanSAging-associated oxidative stress leads to decrease in IAS tone via RhoA/ROCK downregulationAm J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol201430611G983G99124742984

- Lewicky-GauppCHamiltonQAshton-MillerJHuebnerMDeLanceyJOFennerDEAnal sphincter structure and function relationships in aging and fecal incontinenceAm J Obstet Gynecol20092005559.e1e559.e519136096

- GundlingFSeidlHScalercioNSchmidtTScheppWPehlCInfluence of gender and age on anorectal function: normal values from anorectal manometry in a large caucasian populationDigestion201081420721320110704

- RaoSSDyssynergic defecationGastroenterol Clin North Am20013019711411394039

- ScheyRCromwellJRaoSSMedical and surgical management of pelvic floor disorders affecting defecationAm J Gastroenterol20121071116241633 quiz p.163422907620

- Loening-BauckeVAnurasSEffects of age and sex on anorectal manometryAm J Gastroenterol198580150533966455

- Loening-BauckeVAnurasSAnorectal manometry in healthy elderly subjectsJ Am Geriatr Soc19843296366396470379

- McHughSMDiamantNEEffect of age, gender, and parity on anal canal pressures. Contribution of impaired anal sphincter function to fecal incontinenceDig Dis Sci19873277267363595385

- OrrWCChenCLAging and neural control of the GI tract: IV. Clinical and physiological aspects of gastrointestinal motility and agingAm J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol20022836G1226G123112433662

- MadsenJLGraffJEffects of ageing on gastrointestinal motor functionAge Ageing200433215415914960431

- MelkerssonMAnderssonHBosaeusIFalkhedenTIntestinal transit time in constipated and non-constipated geriatric patientsScand J Gastroenterol19831855935976675181

- WiskurBGreenwood-Van MeerveldBThe aging colon: the role of enteric neurodegeneration in constipationCurr Gastroenterol Rep201012650751220878508

- EvansJMFlemingKCTalleyNJSchleckCDZinsmeisterARMeltonLJRelation of colonic transit to functional bowel disease in older people: a population-based studyJ Am Geriatr Soc199846183879434670

- MeierRBeglingerCDederdingJPInfluence of age, gender, hormonal status and smoking habits on colonic transit timeNeurogastroenterol Motil1995742352388574912

- SallesNBasic mechanisms of the aging gastrointestinal tractDig Dis200725211211717468545

- NullensSNelsenTCamilleriMRegional colon transit in patients with dys-synergic defaecation or slow transit in patients with constipationGut20126181132113922180057

- ShinACamilleriMNadeauAInterpretation of overall colonic transit in defecation disorders in males and femalesNeurogastroenterol Motil201325650250823406422

- WaldAHindsJPCaruanaBJPsychological and physiological characteristics of patients with severe idiopathic constipationGastroenterology19899749329372777045

- MerkelISLocherJBurgioKTowersAWaldAPhysiologic and psychologic characteristics of an elderly population with chronic constipationAm J Gastroenterol19938811185418598237932

- TowersALBurgioKLLocherJLMerkelISSafaeianMWaldAConstipation in the elderly: influence of dietary, psychological, and physiological factorsJ Am Geriatr Soc19944277017068014342

- IrvineEJFerrazziSParePThompsonWGRanceLHealth-related quality of life in functional GI disorders: focus on constipation and resource utilizationAm J Gastroenterol20029781986199312190165

- NehraVBruceBKRath-HarveyDMPembertonJHCamilleriMPsychological disorders in patients with evacuation disorders and constipation in a tertiary practiceAm J Gastroenterol20009571755175810925980

- RaoSSTutejaAKVellemaTKempfJStessmanMDyssynergic defecation: demographics, symptoms, stool patterns, and quality of lifeJ Clin Gastroenterol200438868068515319652

- TalleyNJO’KeefeEAZinsmeisterARMeltonLJ3rdPrevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly: a population-based studyGastroenterology199210238959011537525

- LemboACamilleriMChronic constipationN Engl J Med2003349141360136814523145

- HarariDGurwitzJHAvornJBohnRMinakerKLHow do older persons define constipation? Implications for therapeutic managementJ Gen Intern Med199712163669034948

- TalleyNJWeaverALZinsmeisterARMeltonLJFunctional constipation and outlet delay: a population-based studyGastroenterology199310537817908359649

- RaoSSOzturkRStessmanMInvestigation of the pathophysiology of fecal seepageAm J Gastroenterol200499112204220915555003

- DrossmanDALiZAndruzziEU.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impactDig Dis Sci1993389156915808359066

- LockeGR3rdZinsmeisterARFettSLMeltonLJ3rdTalleyNJOverlap of gastrointestinal symptom complexes in a US communityNeurogastroenterol Motil2005171293415670261

- KolarGJCamilleriMBurtonDNadeauAZinsmeisterARPrevalence of colonic motor or evacuation disorders in patients presenting with chronic nausea and vomiting evaluated by a single gastroenterologist in a tertiary referral practiceNeurogastroenterol Motil201426113113824118658

- TalleyNJHow to do and interpret a rectal examination in gastroenterologyAm J Gastroenterol2008103482082218397419

- TantiphlachivaKRaoPAttaluriARaoSSDigital rectal examination is a useful tool for identifying patients with dyssynergiaClin Gastroenterol Hepatol201081195596020656061

- PatriquinHMartelliHDevroedeGBarium enema in chronic constipation: is it meaningful?Gastroenterology1978754619622710831

- PepinCLadabaumUThe yield of lower endoscopy in patients with constipation: survey of a university hospital, a public county hospital, and a Veterans Administration medical centerGastrointest Endosc200256332533212196767

- RaoSSSinghSClinical utility of colonic and anorectal manometry in chronic constipationJ Clin Gastroenterol201044959760920679903

- LeeBEKimGHHow to perform and interpret balloon expulsion testJ Neurogastroenterol Motil201420340740924948132

- RaoSSOzturkRLaineLClinical utility of diagnostic tests for constipation in adults: a systematic reviewAm J Gastroenterol200510071605161515984989

- FletcherJGBusseRFRiedererSJMagnetic resonance imaging of anatomic and dynamic defects of the pelvic floor in defecatory disordersAm J Gastroenterol200398239941112591061

- MetcalfAMPhillipsSFZinsmeisterARMacCartyRLBeartRWWolffBGSimplified assessment of segmental colonic transitGastroenterology198792140473023168

- HintonJMLennard-JonesJEYoungACA new method for studying gut transit times using radioopaque markersGut196910108428475350110

- StivlandTCamilleriMVassalloMScintigraphic measurement of regional gut transit in idiopathic constipationGastroenterology199110111071152044899

- RaoSSCamilleriMHaslerWLEvaluation of gastrointestinal transit in clinical practice: position paper of the American and European Neurogastroenterology and Motility SocietiesNeurogastroenterol Motil201123182321138500

- LeeYYErdoganARaoSSHow to assess regional and whole gut transit time with wireless motility capsuleJ Neurogastroenterol Motil201420226527024840380

- RaoSSCoss-AdameEValestinJMysoreKEvaluation of constipation in older adults: radioopaque markers (ROMs) versus wireless motility capsule (WMC)Arch Gerontol Geriatr201255228929422572600

- BourasEPTangalosEGChronic Constipation in the ElderlyGastroenterology Clinics200938346348019699408

- SuaresNCFordACSystematic review: the effects of fibre in the management of chronic idiopathic constipationAliment Pharmacol Ther201133889590121332763

- FordACMoayyediPLacyBETask Force on the Management of Functional Bowel DisordersAmerican College of Gastroenterology monograph on the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipationAm J Gastroenterol2014109Suppl 1S2S26 quiz 2725091148

- BrandtLJPratherCMQuigleyEMSchillerLRSchoenfeldPTalleyNJSystematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North AmericaAm J Gastroenterol2005100Suppl 1S5S2116008641

- FordACSuaresNCEffect of laxatives and pharmacological therapies in chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysisGut201160220921821205879

- WaldAIs chronic use of stimulant laxatives harmful to the colon?J Clin Gastroenterol200336538638912702977

- Müller-LissnerSAKammMAScarpignatoCWaldAMyths and misconceptions about chronic constipationAm J Gastroenterol2005100123224215654804

- JonesMPTalleyNJNuytsGDuboisDLack of objective evidence of efficacy of laxatives in chronic constipationDig Dis Sci200247102222223012395895

- NybergCHendelJNielsenOHThe safety of osmotically acting cathartics in colonic cleansingNat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol201071055756420736921

- RamkumarDRaoSSEfficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic reviewAm J Gastroenterol2005100493697115784043

- CastleSCCantrellMIsraelDSSamuelsonMJConstipation prevention: empiric use of stool softeners questionedGeriatrics1991461184861718823

- LeungFWRaoSSApproach to fecal incontinence and constipation in older hospitalized patientsHosp Pract (1995)20113919710421441765

- SédabaBAzanzaJRCampaneroMAGarcia-QuetglasEMuñozMJMarcoSEffects of a 250-mL enema containing sodium phosphate on electrolyte concentrations in healthy volunteers: An open-label, randomized, controlled, two-period, crossover clinical trialCurr Ther Res Clin Exp200667533434924678106

- SchmelzerMSchillerLRMeyerRRugariSMCasePSafety and effectiveness of large-volume enema solutionsAppl Nurs Res200417426527415573335

- JohansonJFWaldATougasGEffect of tegaserod in chronic constipation: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trialClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20042979680515354280

- KammMAMüller-LissnerSTalleyNJTegaserod for the treatment of chronic constipation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multinational studyAm J Gastroenterol2005100236237215667494

- BourasEPCamilleriMBurtonDDThomfordeGMcKinzieSZinsmeisterARPrucalopride accelerates gastrointestinal and colonic transit in patients with constipation without a rectal evacuation disorderGastroenterology2001120235436011159875

- CamilleriMKerstensRRykxAVandeplasscheLA placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipationN Engl J Med2008358222344235418509121

- CamilleriMBeyensGKerstensRRobinsonPVandeplasscheLSafety assessment of prucalopride in elderly patients with constipation: a double-blind, placebo-controlled studyNeurogastroenterol Motil200921121256e11719751247

- DrossmanDACheyWDJohansonJFClinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome – results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studiesAliment Pharmacol Ther200929332934119006537

- JohansonJFDrossmanDAPanasRWahleAUenoRClinical trial: phase 2 study of lubiprostone for irritable bowel syndrome with constipationAliment Pharmacol Ther200827868569618248656

- JohansonJFMortonDGeenenJUenoRMulticenter, 4-week, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of lubiprostone, a locally-acting type-2 chloride channel activator, in patients with chronic constipationAm J Gastroenterol2008103117017717916109

- BharuchaAELindenDRLinaclotide – a secretagogue and antihyperalgesic agent – what next?Neurogastroenterol Motil201022322723120377786

- Vazquez RoqueMCamilleriMLinaclotide, a synthetic guanylate cyclase C agonist, for the treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders associated with constipationExpert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol20115330131021651347

- BharuchaAERaoSSAn update on anorectal disorders for gastroenterologistsGastroenterology201414613745 e224211860

- RaoSSValestinJBrownCKZimmermanBSchulzeKLong-term efficacy of biofeedback therapy for dyssynergic defecation: randomized controlled trialAm J Gastroenterol2010105489089620179692

- ChiarioniGWhiteheadWEPezzaVMorelliABassottiGBiofeedback is superior to laxatives for normal transit constipation due to pelvic floor dyssynergiaGastroenterology2006130365766416530506

- RaoSSSeatonKMillerMRandomized controlled trial of biofeedback, sham feedback, and standard therapy for dyssynergic defecationClin Gastroenterol Hepatol20075333133817368232

- HeymenSScarlettYJonesKRingelYDrossmanDWhiteheadWERandomized, controlled trial shows biofeedback to be superior to alternative treatments for patients with pelvic floor dyssynergia-type constipationDis Colon Rectum200750442844117294322

- SimónMABuenoAMBehavioural treatment of the dyssynergic defecation in chronically constipated elderly patients: a randomized controlled trialAppl Psychophysiol Biofeedback200934427327719618262

- HassanIPembertonJHYoung-FadokTMIleorectal anastomosis for slow transit constipation: long-term functional and quality of life resultsJ Gastrointest Surg2006101013301336 discussion 1336–133717175451

- GladmanMAKnowlesCHSurgical treatment of patients with constipation and fecal incontinenceGastroenterol Clin North Am200837360562518793999

- KnowlesCHScottMLunnissPJOutcome of colectomy for slow transit constipationAnn Surg1999230562763810561086

- RotholtzNAWexnerSDSurgical treatment of constipation and fecal incontinenceGastroenterol Clin North Am200130113116611394027

- KammMAHawleyPRLennard-JonesJELateral division of the puborectalis muscle in the management of severe constipationBr J Surg19887576616633416122

- KammMADuddingTCMelenhorstJSacral nerve stimulation for intractable constipationGut201059333334020207638

- MariaGCadedduFBrandaraFMarnigaGBrisindaGExperience with type A botulinum toxin for treatment of outlet-type constipationAm J Gastroenterol2006101112570257517029615

- FariedMEl NakeebAYoussefMOmarWEl MonemHAComparative study between surgical and non-surgical treatment of anismus in patients with symptoms of obstructed defecation: a prospective randomized studyJ Gastrointest Surg20101481235124320499203

- VerneGNDavisRHRobinsonMEGordonJMEakerEYSninksyCATreatment of chronic constipation with colchicine: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trialAm J Gastroenterol20039851112111612809836

- SofferEEMetcalfALaunspachJMisoprostol is effective treatment for patients with severe chronic constipationDig Dis Sci19943959299338174433

- RoartyTPWeberFSoykanIMcCallumRWMisoprostol in the treatment of chronic refractory constipation: results of a long-term open label trialAliment Pharmacol Ther1997116105910669663830

- GhoshalUCSrivastavaDVermaAMisraASlow transit constipation associated with excess methane production and its improvement following rifaximin therapy: a case reportJ Neurogastroenterol Motil201117218518821602997

- AttaluriAJacksonMValestinJRaoSSMethanogenic flora is associated with altered colonic transit but not stool characteristics in constipation without IBSAm J Gastroenterol201010561407141119953090