Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the association between periodontal disease (PD) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and evaluate the effect of dental prophylaxis on the incidence rate (IR) of AMI.

Methods

The Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000 from the National Health Insurance program was used to identify 511,630 patients with PD and 208,713 without PD during 2000–2010. Subjects with PD were grouped according to treatment (dental prophylaxis, intensive treatment, and PD without treatment). The IRs of AMI during the 10-year follow-up period were compared among groups. Cox regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status, residential urbanicity, and comorbidities was used to evaluate the effect of PD treatment on the incidence of AMI.

Results

The IR of AMI among subjects without PD was 0.19%/year. Among those with PD, the IR of AMI was lowest in the dental prophylaxis group (0.11%/year), followed by the intensive treatment (0.28%/year) and PD without treatment (0.31%/year; P<0.001) groups. Cox regression showed that the hazard ratio (HR) for AMI was significantly lower in the dental prophylaxis group (HR =0.90, 95% confidence interval =0.86–0.95) and higher in the intensive treatment (HR =1.09, 95% confidence interval =1.03–1.15) and PD without treatment (HR =1.23, 95% confidence interval =1.13–1.35) groups than in subjects without PD.

Conclusion

PD is associated with a higher risk of AMI, which can be reduced by dental prophylaxis to maintain periodontal health.

Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with a prevalence ranging from 2%–20%.Citation1,Citation2 Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a CHD-related event that may result in sudden death. The risk factors for CHD include age, male sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, smoking, and inflammatory diseases, such as periodontal disease (PD).Citation3–Citation6

About 20%–50% of the population worldwide has PD.Citation7–Citation9 This disease is caused by the accumulation of a specific bacterial biofilm around teeth. The initial presentation is reversible gingivitis, which can be treated after biofilm removal.Citation10–Citation12 As PD progresses, destruction of the periodontal connective tissue and alveolar bone ultimately lead to tooth loss.Citation13 Increased tooth brushing frequency has been found to reduce the serum concentrations of C-reactive protein and fibrinogen, suggesting that the improvement of periodontal conditions can reduce a patient’s systemic inflammatory status.Citation14

Some previous researchers have concluded that poor periodontal status is associated with an increased risk of CHD.Citation13,Citation15–Citation18 Deep periodontal pockets have been found in individuals who have experienced AMI and have been associated with an increased incidence of this event.Citation19–Citation21 A larger variation of subgingival anaerobic microflora has also been observed in those who have experienced AMI and is considered to be a potential risk indicator.Citation22,Citation23 However, other reports showed no significant relationship between PD and CHD.Citation24,Citation25 The relationships of PD and its treatment with the incidence of AMI remain unclear.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using the Taiwanese National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) to estimate the incidence rates (IRs) of AMI among subjects with PD and different PD treatment groups.

Methods

This study received full review by the local institutional review board (Taipei City Hospital Institutional Review Board number: TCHIRB-1020705-E). The institutional review board waived the need for written informed consent from study subjects because all potentially patient-identifying information was encrypted.

Data source

The compulsory, universal National Health Insurance (NHI) program in Taiwan covers up to 99% of the nation’s inhabitants. In conjunction with the NHI Bureau, the National Health Research Institute established the NHIRD to provide useful epidemiological information for basic and clinical research in Taiwan. The National Health Research Institute administers the NHIRD in a manner that ensures all beneficiaries’ privacy and confidentiality, and provides access to researchers only upon ethical approval.

For this study, the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2000 (LHID 2000) was used. The LHID 2000 is a standardized sample file for research use provided by the National Health Research Institute, and consists of comprehensive use and enrollment information for a randomly selected sample of 1 million NHI beneficiaries, representing approximately 5% of all enrollees in Taiwan in 2000. A multistage stratified systematic sampling design was used and it was found that there were no statistically significant differences in sex or age between the sample group and all enrollees. The identification of patients in the LHID 2000 is encrypted to protect their privacy, as this database includes information about medical orders, treatment procedures, and medical diagnoses (coded based on the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM]).

Study cohort

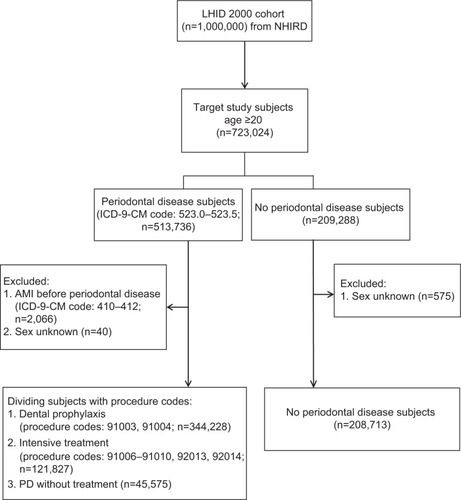

The cohort for this retrospective study was drawn from 1 million beneficiaries sampled randomly from all beneficiaries listed in the NHIRD in the year 2000 (ie, the LHID 2000). Only subjects aged ≥20 years were included (723,024 beneficiaries; ). The subjects were included into the PD cohort if they visited an ambulatory care provider due to PD (ICD-9-CM codes 523.0–523.5) during the study period. Patients who developed AMI before PD diagnosis (n=2,066) and individuals of unknown sex (n=615) were excluded. Individuals with no diagnosis of PD from 2000–2010 served as the control group (n=208,713; followed for 2,248,618 person-years).

Figure 1 Selection of study patients.

The PD group (ICD-9-CM codes 523.0–523.5) was divided into three treatment groups:

Dental prophylaxis (n=344,228; followed for 2,807,865 person-years): PD patients who only received dental prophylaxis (procedure codes: 91003, 91004) during the following period.

Intensive treatment (n=121,827; followed for 789,518 person-years): PD patients who received treatments such as subgingival curettage and root planning (procedure codes: 91006–91008) and/or periodontal flap operation (procedure codes: 91009, 91010) and/or tooth extraction (procedure codes: 92013, 92014).

PD without treatment (n=45,575; followed for 170,754 person-years): PD patients who received no treatments.

Thus, a total of 720,343 subjects followed for 6,016,755 person-years were included in this study. Participants were followed from the cohort entry date (the first date of an ambulatory care visit due to PD for the PD group and January 1, 2000 for the control group) until the date of hospitalization due to AMI (ICD-9-CM codes 410–412), death, or end of the study period (December 31, 2010).

The socioeconomic status variable had five categories. People with a well-defined monthly payroll were classified into three categories: =NT$40,000, NT$20,000–$39,999, and <NT$20,000 (NT$: New Taiwan dollars; US$1 is approximately worth NT$30). People without a well-defined monthly wage could either enroll through unions or associations, such as farmers’ associations, or through local government offices. Those who enrolled through local government offices included self-employed, retirees, corner store owners, or low-income people. People without a well-defined monthly payroll were categorized into two groups: union or association members and people enrolled in local government offices.

The residential urbanicity was classified into three categories: urban classification for metropolitan cities; suburban classification for all other cities and counties; and rural classification for all townships and rural areas.

In the analysis of AMI comorbidities, including atrial fibrillation (ICD-9-CM code 437.3), diabetes (ICD-9-CM code 250), hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes 401–405), dyslipidemia (ICD-9-CM code 272), chronic kidney disease (ICD-9-CM code 585), and peripheral vascular disease (ICD-9-CM codes 440.2, 440.3, 440.9, 443, 444.21, 444.22), only subjects with more than three outpatient visits during the study period were included to increase the validity of diagnoses in the administrative data set.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS® statistical package (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The IRs of AMI among patients with PD and control subjects were compared. The χ2 test was used for parametric categorical data. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to determine whether PD is a risk factor for the development of AMI. This model was adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status, residential urbanicity, PD treatment, and comorbidities (atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, and peripheral vascular disease).

Results

A total of 10,046 patients developed AMI during the follow-up period (IR =0.17%/year; ). The IR of AMI increased with age from 0.03%/year among subjects aged 20–44 years to 0.24% and 0. 61%/year among those aged 45–64 years and >65 years, respectively (P<0.001). The IR of AMI was higher among men than women (0.21% versus 0.13%/year) and was significantly higher among subjects with atrial fibrillation (0.88%/year), diabetes mellitus (0.55%/year), hypertension (0.49%/year), dyslipidemia (0.37%/year), chronic kidney disease (0.87%/year), and peripheral vascular disease (0.52%/year) than people without these comorbidities (all P<0.001).

Table 1 Univariate analysis of factors affecting the incidence of acute myocardial infarction

A total of 4,327 people without PD developed AMI (IR =0.19%/year). Among those with PD, the IR of AMI was lowest in the dental prophylaxis group (0.11%/year) and highest in the PD without treatment group (0.31%/year; P<0.001).

When comparing IRs of AMI after being stratified by age, sex, socioeconomic status, residential urbanicity, and comorbidity variables (), the lowest IR of the PD population always appeared in the dental prophylaxis group, followed by the intensive treatment group and PD without treatment group (P<0.001 or P=0.013 for the trend test).

Table 2 Acute myocardial infarction prevalence among study subjects by periodontal disease types

Cox regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, socioeconomic status, residential urbanicity, and comorbidities showed that the HR of AMI was significantly lower in the dental prophylaxis group (HR =0.90, 95% CI =0.86–0.95) and higher in the intensive treatment (HR =1.09, 95% CI =1.03–1.15) and PD without treatment (HR =1.23, 95% CI =1.13–1.35) groups than among subjects with no PD (). The r2 correlate of the Cox regression model was 2.38%.

Table 3 Results of Cox regression analysis conducted to identify predictors of acute myocardial infarction development

Discussion

This is the first nationwide, population-based study to examine the strength of association between periodontal treatment and the incidence of AMI. The results of this study demonstrated that PD is a significant risk factor for AMI, and that dental prophylaxis protects against AMI development.

The findings support the concept that inflammatory diseases such as PD may play a role in the pathogenesis of AMI. The association of PD with the prevalence of CHD suggests that inflammation may be a potential mechanism involved in the regulation of the atherosclerotic process.Citation26,Citation27 PD may induce immune cells to secrete the inflammatory cytokines thromboxane A2, interleukin 1β, prostaglandin E2, and tumor necrosis factor α, which trigger and exacerbate atherogenetic and thromboembolic processes, resulting in CHD.Citation26,Citation28–Citation30 Poor periodontal condition was also reported to be associated significantly with an increased concentration of C-reactive protein,Citation31–Citation34 a well-studied inflammatory marker and an independent predictor of CHD.Citation35,Citation36 In addition to circulating inflammatory factors, oral microbial organelles circulating in the blood have been proposed to lead to the increased incorporation of PD pathogens in atherosclerotic plaque.Citation26,Citation37 The attached PD pathogens can then adhere to vascular cells, inducing vascular infection and atherothrombosis and eventually causing AMI.Citation38

The HRs among the different PD treatment groups were statistically significantly different. Sometimes this can be due to the very huge sample size used. However, the authors believe that the difference of HR among PD treatment groups had clinical significance. Other different approaches to PD-related conditions also showed a similar finding in the association with AMI. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III cohort study found that patients with severe PD had a four-fold higher risk of myocardial infarction than those without PD.Citation39 Infections of dental origin have also been documented in patients experiencing myocardial infarction.Citation40 Periodontal pocket depth has been reported to be associated with the IR of AMI.Citation19,Citation20 Tooth loss, an indicator of PD history, was significantly related to carotid intima-media thickness, a strong predictor of myocardial infarction and stroke.Citation37,Citation41 Treatment of PD resulting in a beneficial effect on vascular diseases such as AMI and stroke was also reported.Citation42–Citation44 The results of a cross-sectional randomized clinical study suggested that nonintensive, Phase I periodontal therapy decreased serum immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin M levels in patients who developed AMI.Citation42 A 7-year cohort study by Chen et al showed that frequent tooth scaling reduced the IR and risk of AMI among subjects aged >50 years.Citation43 In a previous study, it was found that dental prophylaxis reduced the risk of ischemic stroke in subjects with PD, especially those aged 20–44 years.Citation44

Several limitations of this study must be considered. First, the use of administrative data and the retrospective design may have resulted in bias with respect to diagnoses. A further concern is the nonresponder bias/selection bias. Although the NHI program in Taiwan covered up to 99% of the nation’s inhabitants and provides free dental check-ups and prophylaxis twice a year to promote the prevention of PD, some PD patients may not be included in this NHI database because they did not have health insurance or did not seek treatment or check-up. However, the NHI Bureau routinely samples patient charts in different medical centers to validate database quality and minimize miscoding or misclassification. In addition, patients with PD were identified using both ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes and PD treatment codes in this study to minimize classification errors. Only patients with more than three outpatient visits were included in the analysis of AMI and comorbidities to reduce nondifferential misclassification bias. Second, the lack of information provided by the NHIRD on other risk factors for PD and AMI, such as education, family history, body mass index, and smoking status, could reduce the feasibility and accuracy of the interpretation of analytical outcomes. However, several recent studies have indicated that the significant associations of PD with AMI and recurrent cardiovascular events in patients developing myocardial infarction are independent of smoking status.Citation34,Citation45–Citation47 PD has also been demonstrated to contribute to elevated C-reactive protein levels in nondiabetic, nonsmoking patients who have experienced AMI.Citation48

Conclusion

The current study demonstrated that PD is correlated with the risk of AMI, and that dental prophylaxis can significantly reduce the IR of AMI. Patients who receive regular prophylactic dental treatment are more likely to have healthier periodontal conditions and less likely to have systemic chronic inflammatory reactions, resulting in a lower IR of AMI.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. All authors take responsibility for all aspects of the reliability and freedom from bias of the data presented and their discussed interpretation.

References

- RogerVLGoASLloyd-JonesDMHeart disease and stroke statistics – 2012 update: a report from the American Heart AssociationCirculation20121251e2e22022179539

- Management of stable angina pectorisRecommendations of the Task Force of the European Society of CardiologyEur Heart J19971833944139076376

- GreenlandPKnollMDStamlerJMajor risk factors as antecedents of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease eventsJAMA2003290789189712928465

- KiechlSEggerGMayrMChronic infections and the risk of carotid atherosclerosis: prospective results from a large population studyCirculation200110381064107011222467

- DietrichTJimenezMKrall KayeEAVokonasPSGarciaRIAge- dependent associations between chronic periodontitis/edentulism and risk of coronary heart diseaseCirculation2008117131668167418362228

- SanzMD’AiutoFDeanfieldJFernandez-AvilesFEuropean workshop in periodontal health and cardiovascular disease – scientific evidence on the association between periodontal and cardiovascular diseases: a review of the literatureEur Heart J Suppl201012Suppl BB3B12

- AlbandarJMRamsTEGlobal epidemiology of periodontal diseases: an overviewPeriodontol 200020022971012102700

- DyeBATanSSmithVTrends in oral health status: United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004Vital Health Stat 11200724819217633507

- AlbandarJMUnderestimation of periodontitis in NHANES surveysJ Periodontol201182333734121214340

- PetersenPEOgawaHStrengthening the prevention of periodontal disease: the WHO approachJ Periodontol200576122187219316332229

- SocranskySHaffajeeAMicrobiology of Periodontal Disease: introductionPeriodontology200538912

- PasterBJBochesSKGalvinJLBacterial diversity in human subgingival plaqueJ Bacteriol2001183123770378311371542

- PihlstromBLMichalowiczBSJohnsonNWPeriodontal diseasesLancet200536694991809182016298220

- de OliveiraCWattRHamerMToothbrushing, inflammation, and risk of cardiovascular disease: results from Scottish Health SurveyBMJ2010340c245120508025

- LoescheWJSchorkATerpenningMSChenYMKerrCDominguezBLThe relationship between dental disease and cerebral vascular accident in elderly United States veteransAnn Periodontol1998311611749722700

- WuTTrevisanMGencoRJDornJPFalknerKLSemposCTPeriodontal disease and risk of cerebrovascular disease: the first National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and its follow-up studyArch Intern Med2000160182749275511025784

- BahekarAASinghSSahaSMolnarJAroraRThe prevalence and incidence of coronary heart disease is significantly increased in periodontitis: a meta-analysisAm Heart J2007154583083717967586

- HumphreyLLFuRBuckleyDIFreemanMHelfandMPeriodontal disease and coronary heart disease incidence: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Gen Intern Med200823122079208618807098

- EmingilGBuduneliEAliyevAAkilliAAtillaGAssociation between periodontal disease and acute myocardial infarctionJ Periodontol200071121882188611156045

- GeertsSOLegrandVCharpentierJAlbertARompenEHFurther evidence of the association between periodontal conditions and coronary artery diseaseJ Periodontol20047591274128015515345

- AndriankajaOMGencoRJDornJThe use of different measurements and definitions of periodontal disease in the study of the association between periodontal disease and risk of myocardial infarctionJ Periodontol20067761067107316734583

- DoganBBuduneliEEmingilGCharacteristics of periodontal microflora in acute myocardial infarctionJ Periodontol200576574074815898935

- SteinJMKuchBConradsGClinical periodontal and microbiologic parameters in patients with acute myocardial infarctionJ Periodontol200980101581158919792846

- HujoelPPDrangsholtMSpiekermanCDeRouenTAPeriodontal disease and coronary heart disease riskJAMA2000284111406141010989403

- HowellTHRidkerPMAjaniUAHennekensCHChristenWGPeriodontal disease and risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease in U.S. male physiciansJ Am Coll Cardiol200137244545011216961

- LockhartPBBolgerAFPapapanouPNPeriodontal disease and atherosclerotic vascular disease: does the evidence support an independent association? A scientific statement from the American Heart AssociationCirculation2012125202520254422514251

- ScannapiecoFABushRBPajuSAssociations between periodontal disease and risk for atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. A systematic reviewAnn Periodontol200381385314971247

- SteinJMSmeetsRReichertSThe role of the composite interleukin-1 genotype in the association between periodontitis and acute myocardial infarctionJ Periodontol20098071095110219563289

- LoweGDThe relationship between infection, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease: an overviewAnn Periodontol2001611811887452

- MustaphaIZDebreySOladubuMUgarteRMarkers of systemic bacterial exposure in periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review and meta-analysisJ Periodontol200778122289230218052701

- WuTTrevisanMGencoRJFalknerKLDornJPSemposCTExamination of the relation between periodontal health status and cardiovascular risk factors: serum total and high density lipoprotein cholesterol, C-reactive protein, and plasma fibrinogenAm J Epidemiol2000151327328210670552

- RidkerPMSilvertownJDInflammation, C-reactive protein, and atherothrombosisJ Periodontol2008798 Suppl1544155118673009

- NoackBGencoRJTrevisanMGrossiSZambonJJDe NardinEPeriodontal infections contribute to elevated systemic C-reactive protein levelJ Periodontol20017291221122711577954

- DeliargyrisENMadianosPNKadomaWPeriodontal disease in patients with acute myocardial infarction: prevalence and contribution to elevated C-reactive protein levelsAm Heart J200414761005100915199348

- YeboahJMcClellandRLPolonskyTSComparison of novel risk markers for improvement in cardiovascular risk assessment in intermediate-risk individualsJAMA2012308878879522910756

- Di NapoliMSchwaningerMCappelliREvaluation of C-reactive protein measurement for assessing the risk and prognosis in ischemic stroke: a statement for health care professionals from the CRP Pooling Project membersStroke20053661316132915879341

- DesvarieuxMDemmerRTRundekTPeriodontal microbiota and carotid intima-media thickness: the Oral Infections and Vascular Disease Epidemiology Study (INVEST)Circulation2005111557658215699278

- DornBRDunnWAJrProgulske-FoxAInvasion of human coronary artery cells by periodontal pathogensInfect Immun199967115792579810531230

- ArbesSJJrSladeGDBeckJDAssociation between extent of periodontal attachment loss and self-reported history of heart attack: an analysis of NHANES III dataJ Dent Res199978121777178210598906

- WillershausenBKasajAWillershausenIAssociation between chronic dental infection and acute myocardial infarctionJ Endod200935562663019410072

- DesvarieuxMDemmerRTRundekTRelationship between periodontal disease, tooth loss, and carotid artery plaque: the Oral Infections and Vascular Disease Epidemiology Study (INVEST)Stroke20033492120212512893951

- GunupatiSChavaVKKrishnaBPEffect of Phase I periodontal therapy on anti-cardiolipin antibodies in patients with acute myocardial infarction associated with chronic periodontitisJ Periodontol201182121657166421486181

- ChenZYChiangCHHuangCCThe association of tooth scaling and decreased cardiovascular disease: a nationwide population-based studyAm J Med2012125656857522483056

- LeeYLHuHYHuangNHwangDKChouPChuDDental prophylaxis and periodontal treatment are protective factors to ischemic strokeStroke20134441026103023422085

- AndriankajaOMGencoRJDornJPeriodontal disease and risk of myocardial infarction: the role of gender and smokingEur J Epidemiol2007221069970517828467

- MattilaKJNieminenMSValtonenVVAssociation between dental health and acute myocardial infarctionBMJ198929866767797812496855

- DornJMGencoRJGrossiSGPeriodontal disease and recurrent cardiovascular events in survivors of myocardial infarction (MI): the Western New York Acute MI StudyJ Periodontol201081450251120367093

- KodovazenitisGPitsavosCPapadimitriouLPeriodontal disease is associated with higher levels of C-reactive protein in non-diabetic, non-smoking acute myocardial infarction patientsJ Dent2011391284985421946158